THE FILMS OF LARRY COHEN AND GEORGE ROMERO

Only the major artist—or the incorrigibly obsessive one, which sometimes amounts to the same thing—is capable of standing against the flow of his period (with the concomitant dangers of isolation, of becoming fixed in an embattled position): a truism greatly compounded by the commercial nature of cinema and the problems of financing and distribution. The minor talent thrives only when the climate is congenial, when the tradition within which it operates is nourished into vigorous growth from sources within the culture. Such, precisely, is the case with the 70s horror film: within the period, within the genre, a remarkable number of talents were able to produce work of vitality, force and complexity. None has convincingly survived the retrenchments of the 80s. The 70s crisis in ideological confidence temporarily released our culture’s monsters from the shackles of repression. The interesting horror films of the period, without a single exception, are characterized by the recognition not only that the monster is the product of normality, but that it is no longer possible to view normality itself as other than monstrous. I examine here the work of the two directors who produced the most consistent and impressive bodies of work, then consider briefly a number of miscellaneous horror films from the same period. What is perhaps the most brilliant of all 70s horror films—De Palma’s Sisters—must wait till the next chapter.

LARRY COHEN: WORLD OF GODS AND MONSTERS

An attempt to define Cohen’s work can profitably begin by comparing it with De Palma’s; their careers to date offer remarkable parallels that serve to illuminate the differences. In their early works both directors use blacks as a threat to white supremacy, a variant on the return of the repressed theme: De Palma in the extraordinary “Be Black, Baby” section of Hi, Mom! (and, although not presented as a threat, Philip in Sisters is relevant here); Cohen in Black Caesar, Hell Up in Harlem, and, very impressively, in Bone. Both directors attempted overtly experimental works early in their careers, disrupting the conventions of realist narrative (Greetings, Hi Mom!; Bone). Both have returned repeatedly to the horror film (Sisters, Carrie, The Fury; It’s Alive, God Told Me To, It Lives Again). Both have abandoned their early experimentalism, temporarily at least, to express an obviously genuine (not merely commercial) allegiance to the Hollywood tradition. Thus De Palma remade Phantom of the Opera as Phantom of the Paradise, Psycho as Sisters, Vertigo as Obsession, in each case producing a valid variation rather than imitation. In the case of Cohen, the allegiance is expressed less specifically (though Black Caesar very consciously transposes the structure of the 30s gangster film, drawing particularly on Little Caesar and Scarface) but seems even stronger.

One form it takes is Cohen’s extensive use of Hollywood old-timers: Sylvia Sidney and Sam Levene in God Told Me To and most of the cast of The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (Broderick Crawford, Dan Dailey, Celeste Holm, June Havoc, Jose Ferrer). The choice of Miklos Rozsa to score Hoover is also relevant here, Cohen using his “stirring” final music with splendid irony.

The most obvious link is the common debt to Alfred Hitchcock, who, with Shadow of a Doubt, Psycho, The Birds, and Marnie, might reasonably be called the father of the modern horror film. Here one should include Tobe Hooper as well: the buildup to the first killing in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is worthy, shot by shot, of the Master in the sophistication of its suspense devices, its play with suggestion, expectation, relaxation, and the subtle discrepancies between the characters’ awareness and the audience’s. The influence is most obvious in De Palma because deliberately flaunted, an aspect of the signified, but it is clear enough in Cohen, in the overt homage of the staircase assault in God Told Me To and more pervasively in the suspense techniques, including subjective camera, of It’s Alive. Most specifically, both directors used Bernard Herrmann, who composed the scores for Sisters, Obsession, and It’s Alive, and to whom God Told Me To is dedicated; he also received a posthumous credit for the score of It Lives Again.

De Palma’s work has achieved intermittent commercial success and widespread (though still insufficient) critical attention; Cohen’s has achieved neither. It’s Alive did well enough at the box office, but Bone, God Told Me To and Hoover—all very difficult box office propositions requiring careful and intelligent handling—were thrown away. It would be an understatement to say that Cohen’s work is not highly regarded by the bourgeois press: in general, it is ignored; when noticed, vilified. A Film Comment article summarily dismissed It’s Alive as a “Rosemary’s Baby/Exorcist rip-off” (it seems to me more intelligent than either, and owes them about as much as Rio Bravo owes High Noon, the relationship being more of contradiction than influence). No one has bothered to examine Cohen’s work closely enough to recognize its difficulty—difficulty which, although the films are frequently incoherent, can never be reduced to a simple matter of confusion. Cohen has not achieved the brilliance or the coherence of Sisters, but his work in the 70s strikes me as more consistent, and more consistently satisfying, than De Palma’s in the same period.

The word “brilliance” is capable of carrying a hint of pejorative overtones. Carrie and The Fury are also brilliant (indeed, more insistently so than Sisters), and aroused a fear (subsequently neither confirmed nor totally assuaged) that the showman in De Palma was going to take over completely, that the interest of his films, the complexity and urgency of signification, was becoming submerged beneath the desire to dazzle with an ever more flamboyant rhetoric and effects out of all proportion to meaning. Cohen, on the other hand, never attracts attention to himself; his work relates back beyond the director-as-superstar era to the classical Hollywood tradition of directorial self-effacement. I would find it difficult to describe a Cohen visual style that would clearly distinguish his work from the mainstream of contemporary cinema; like a Hawks or a McCarey, he has been content to work within the anonymity of generally accepted stylistic-technical procedures.

There is a problem here, of course: since the days of Hawks and McCarey those procedures have changed drastically, and one can argue that the tradition of filmmaking at the level of basic professionalism has become increasingly debased. The reasons for the sketchiness and sense of haste of Cohen’s films are probably complex, such characteristics not to be accounted for simply in economic terms of low budgets and short shooting schedules, relevant as such conditions clearly are. The realization of the films, or more precisely, their unrealized quality, sometimes testifies to bad habits acquired from television and never quite cast off (useful, no doubt, in the saving of time and money). The conventional, at times perfunctory, ping-pong cross-cutting of dialogue scenes—Hitchcock’s phrase “photographs of people talking” comes to mind—suggests a filmmaker whose ambitions don’t entirely transcend expectations of casual viewing and immediate disposability (the almost total lack of critical recognition—of any interested and considered inquiry into what the films are doing—together with the absence of any sustained commercial success, is not exactly conducive to higher ambitions). It may be, however, that these are the conditions in which Cohen operates most spontaneously and effectively—the urgency and intensity of the films may be partly dependent on the speed with which they are tossed off (I once heard Cohen speculate about the film he would make with the budget De Palma had for The Fury: “Or rather,” he added, “the three or four films”). The frequent impression of something hastily slapped together combines with Cohen’s tendency to go for “impact” (the fondness for the wide-angle lens, choppy editing) to evoke—when the films are noticed at all—the term “schlock,” one of those expressive but extremely ill-defined terms of abuse coined by the bourgeois press to indicate a type of film it considers beneath its level of “educated” taste. Thus the conceptual level of Cohen’s work—the level on which it is most impressive and challenging—is ignored, the term “schlock” actually denying its existence.

Yet this is already to concede too much and to simplify a complex issue. Since a film consists only of sounds and images, some such formula as “bad films with good ideas” simply will not do: there is no conceptual level that is not at least partly realized through the organization of sounds and images. Rough and hasty as they may often appear, Cohen’s films abound in ideas that are up there on the screen, dramatized in action and dialogue, in a mise-en-scène whose lack of refinement is the corollary of its energy and inventiveness. One can point, particularly, to the self-evident excellence with actors: outstanding performances are as much the rule in Cohen’s work as they are the exception in Romero’s. The urgency and intensity I noted as prime characteristics are projected through the performances of, for example, John Ryan and Sharon Farrell in It’s Alive, Kathleen Lloyd and Frederic Forrest in the sequel, and Michael Moriarty in Q. Beyond that, the roughness and the emphasis on impact tend to conceal effects that are both complex and subtle. A close examination of the opening sequences of It’s Alive will convincingly suggest the richness of Cohen’s work at its best, as well as its centrality to the American tradition; it will also lead us directly into major components of the Cohen thematic.

The exposition divides into four segments (according to location): the home (Lenore is awakened by labor pangs, preparations for the hospital); the car (the drive to the hospital, leaving Chris at Charlie’s house en route); the hospital (reception desk, corridors, Lenore’s room); the hospital (waiting room with Frank and the other expectant fathers).

The first segment is built on a disturbing tension between presentation and enacted content. The introductory pan across the dark overhang of a roof, dissolving to a darkened bedroom, accompanied by ominous music, immediately evokes menace and foreboding; what we are shown is a seemingly happy, united, loving family, eager for the birth of the new child. Various stylistic features intensify the uneasiness: the edgy, elliptical editing, the low-angle hand-held tracking shot that rapidly follows the couple down a darkened hallway. But it swiftly becomes clear that this is not a matter of imposing an arbitrary ominousness on perfectly innocent subject matter, a mere business of signaling “This is a horror movie, something terrible is going to happen”: a number of details relate the edginess to the familial relationship.

Lenore’s attitude throughout is apologetic. We see that she is in considerable pain, but we also see her minimizing this for Frank. Even when she subsequently admits that “this one feels different,” her concern seems more for the anxiety she may cause her husband than for her own physical pain. Frank’s method of awakening his son—by applying the family cat to his neck—is at least curious: apparently humorous and affectionate, it also suggests aggression. The disturbing effect of the moment receives its confirmation when, in her hospital bed, Lenore expresses her anxiety lest Frank feel “tied down” again, as he did when they had Chris; we also learn that the couple (on the surface so enthusiastic about the new arrival) considered abortion. Eleven years have passed since the birth of their first child. Chris’ room is decorated with wallpaper redolent of the hippy period, the time, presumably, of Frank and Lenore’s early married life and the birth of Chris: the dominant motif is the word LOVE and its symbol. The detail of décor serves a dual function—the ironic contrast between flower child freedom and suburban domesticity; the need to display, to ‘advertise’, love, that actually calls its reality into question. Frank is in Public Relations, Lenore is the perfect bourgeois wife/mother. Frank stands in the doorway of the newly decorated nursery, surveying it with the air of a proprietor. The camera zooms out to reveal that it is all blue. The moment is answered in the second segment, when Lenore (explaining to her son that he can’t accompany her to the hospital) tells Chris that they’ll phone him and tell him whether he has “a baby sister or a baby brother,” the unexpected order subtly pointed up in Sharon Farrell’s delivery of the line. The suggestion is that the ideal American couple—successful businessman, devoted housewife/mother, seemingly delighted with their ideal arrangement—are in fact profoundly incompatible: what but a “monster” could such a union ultimately produce?

Clearly, the “wandering versus settling antinomy” that Peter Wollen found central to the work of Ford is central to much more: it is one of the structuring tensions within American ideology. It produces the ideal male as the wanderer/adventurer, the ideal female as housewife/mother, taught to build precisely that ‘home’ (literal and metaphorical) within which the man will feel trapped. In the car, a chance remark of Chris sparks off his father’s imitation of Walter Brennan in Red River, an expression of nostalgia for the cattle drives and open prairies of the American past. Whatever the moment’s origin (one’s impression is of a John Ryan improvisation), its inclusion in the film represents a brilliant extension of meaning into reaches of genre and ideology: the affluent, outwardly complacent but inwardly tense and dissatisfied, nuclear family of the 70s related suddenly to the western, the pioneers, and the history/mythology of a heroic past of which they are the present product. During the same segment the freedom/entrapment opposition gets further ramification through the introduction of Charlie, the friend of the family with whom Chris is to stay. Chris is to feel sorry for Charlie because his marriage has broken up and he only sees his kids on weekends: the detail suggests an environment in which the unbroken family is no longer necessarily the norm, with the added irony that poor Charlie here and on subsequent appearances, seems consistently and spontaneously cheerful, in contrast to the strained cheerfulness of Frank and Lenore. The contrast confirms the impression of a marriage held together more by determination and willpower than by genuine desire, the strength of the film lying in the couple’s representativeness (we are never encouraged to view them as monstrous individuals, the tension being firmly presented as arising from social structures and institutions, from ideological assumptions rather than from specific incompatibilities of character).

Nostalgia for a simpler, more primitive, less constricting past is also suggested in the third segment by Frank’s exchange with the Gaelic speaking nurse about “the wee cuddies and the wee cubs.” Again, one has the impression of a detail that developed spontaneously during shooting. Cohen’s readiness to use such moments is an aspect of the surface aliveness of his films; it also adds to their wealth of connotation, in this case associating babies with the young of animals, taking up the animal imagery introduced with the cat (first segment) and developed in the reference to the puppy Chris has been promised as his compensation for the appearance of a sibling (second segment) that will culminate in the birth of the monstrous baby (explicitly referred to as an “animal”).

The second part of the third segment (in Lenore’s room, before she is taken to the delivery room) makes the familial tension explicit in ways already suggested (Lenore’s anxiety lest Frank feel “tied down” again as he did with Chris, the hint that they had considered abortion). The explicitness arises naturally out of the dramatic situation (Lenore frightened by the pain she is experiencing and by her sense that “this one is different,” her pent-up anxieties suddenly released), and its effect is to reinforce our sense of prior suppression—that in this seemingly warm, close, openly affectionate family, difficult issues are not discussed, anxieties never voiced except in extremis.

The most obvious function of the fourth segment (the waiting room) is to suggest (in anticipation) possible explanations for the monstrous baby: pollution and the indiscriminate use of chemicals (a new roach-killer has produced a new, more impregnably immune breed of roaches). Another possible explanation will be offered later: the irresponsible development of inadequately tested medication, birth-control pills, etc. But the “explanations” never get beyond suggestion: none is ever identified as the cause. The effect is not at all to limit the meaning of the baby, but rather to extend it: if it is the product of the contemporary nuclear family, it is also the product of a whole civilization characterized by various forms of greed and irresponsibility, a civilization for which Frank (as public relations man) is apologist and advertiser.

The density of “thinking” (whether conscious or unconscious, for clearly the unconscious thinks)—the network of interrelated connotations—that characterizes this opening is not sustained throughout the film. Passages in the middle seem comparatively thin and stretched, though any shortcomings are redeemed by the film’s magnificent last twenty minutes, which project an anguish (apparently unnoticed by most critics) associated more with an Ingmar Bergman movie than with a “schlock” horror film. (Much work needs to be done on the ways in which packaging predetermines response: reviewers generally seem to see what they have been led to expect to see, whether or not it corresponds to what is actually before their eyes.) A further explanation exists beyond low budgets and temperamental urgency for Cohen’s failure, to date, to produce a wholly satisfying, a wholly convincing movie: that offered in chapter 4 to explain the characteristic incoherence of the most interesting 70s films, and of particular relevance to the horror genre at this stage of its evolution. The “thinking” of the films can lead logically only in one direction, toward a radical and revolutionary position in relation to the dominant ideological norms and the institutions that embody them, and such a position is incompatible with any definable position within mainstream cinema (or even on its exploitation fringes); it is also incompatible with any degree of comfort or security within the dominant culture. The areas of disturbance exposed in the first minutes of It’s Alive—disturbance about heterosexual relations, male/female gender roles, the family, the contemporary development of capitalism, its abuse of technology, its indifference to the pollution of the environment, its crass materialism, callousness, and greed—encompass the entire structure of our civilization, from the corporation to the individual, and the film sees that structure as producing nothing but a monstrosity.

Just as the thematic structure of the horror film cannot be restricted purely to that genre (in general, genres can be clearly distinguished only in terms of their more superficial, iconographic elements), so the thematic structure of Cohen’s work crosses generic boundaries, encompassing besides the horror film the “blaxploitation” movie (Black Caesar), the political biography (The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover), and the crazy comedy (Full Moon High). I shall therefore not restrict the following analysis to Cohen’s horror films.

Three closely interconnected thematic figures recur throughout Cohen’s works and are particularly relevant to a definition of its disturbance.

1. Undercutting the Protagonist as Hero. Insofar as we identify (‘sympathize’ might be a better word here) with Cohen’s male protagonists, it is in order to discover with them how wrong they have been. Frank in It’s Alive is probably the closest to a traditional identification figure in Cohen’s work, and what we share with him is the agonizing movement from repudiation of his child to acceptance of it, though too late to save its life. The films never offer us a ‘correct’ position dramatized within the action in relation to its conflicts. The most intellectually ambitious of Cohen’s works—Bone, God Told Me To, Hoover—carry this furthest. The resolution of each film leaves a sense of dissatisfaction, uncertainty, loss. There is never a suggestion that things can be put right and solutions found within the system; the conflicts are presented as inherent in that system—fundamental and unresolvable.

2. The Double. What I have suggested is the privileged form of the “return of the repressed” is central to the structure of Cohen’s work. One can offer a basic formula, though the films cannot be reduced to mere reiterations of it: the protagonist learns to recognize (or at the very least is haunted by a suspicion of) his identity with the figure he is committed to destroying. Again, It’s Alive provides a particularly clear instance. The exclamatory title, of course, echoes through the horror film, but its strongest association, and presumably its source in the sound film, is James Whale’s Frankenstein. The association is confirmed by the protagonist’s name, Frank, and its significance is made explicit in his dialogue with medical authorities around the film’s midpoint. Frank reminisces that when he was a child he thought “Frankenstein” was the name of the monster, not of its creator, and adds “Somehow the identities get all mixed up, don’t they?”—a line that might stand as epigraph for all Cohen’s films to date. Which is more monstrous, the murderous child or the father who created it and now, like Frankenstein, wants to destroy it? And are parent and offspring clearly distinguishable?–is the child not recognizable as the embodiment of the father’s repressed rage and frustration, his constrained energies? Similarly, God Told Me To moves toward the protagonist’s recognition that the beautiful, destructive “god,” who (through his possessed agents) is terrorizing the city, is his brother and that he himself possesses the same powers, though repressed by his Catholic upbringing. And there is the protagonist of Black Caesar, who blacks with boot polish the face of the policeman who once humiliated him, before killing him, or Hoover, forever haunted by Dillinger (for whose death he was responsible, but whom he wanted to kill in person), preserving his deathmask and collecting his relics.

3. Parents and Children. This most problematic aspect of Cohen’s work may also be the chief source of its energy. It’s Alive clearly depicts its monstrous baby as the logical product of the tensions within the modern nuclear family, its crisis of gender roles. But what are we to make of the fact that the monster’s dominant motivation is to find its family and to be accepted into it? On the one hand, the implication seems to be that the family must recognize and accept what they have produced, that they must account for themselves and for their own monstrousness; on the other, the film seems posited on a nostalgia for traditional family values. The tension seems at the heart of the confusion in Cohen’s work. Certainly, one of the threads connecting some extremely disparate movies is the monstrous child’s striving for recognition by its parents, and the impossibility of such recognition within existing familial codes and structures. Thus we have the son in Bone (alleged by his parents to be a Vietnam prisoner of war and actually in a Spanish jail for dope smuggling, a fate from which the parents have done nothing to extricate him) going into peels of uncontrollable laughter as, thousands of miles away, his mother beats his father to death with her handbag; thus we have “Black Caesar” motivated by an obsessive desire for parental recognition while further alienating both father and mother by his every action; thus we have Hoover’s relationship with his mother, and the painful scene in which the protagonist of God Told Me To tries to gain recognition from his, and is hysterically repudiated. Despite the frequent dominance of the father/son relationship, the core of the problem seems to lie in Cohen’s (and our culture’s) confused and ambivalent attitude to motherhood.

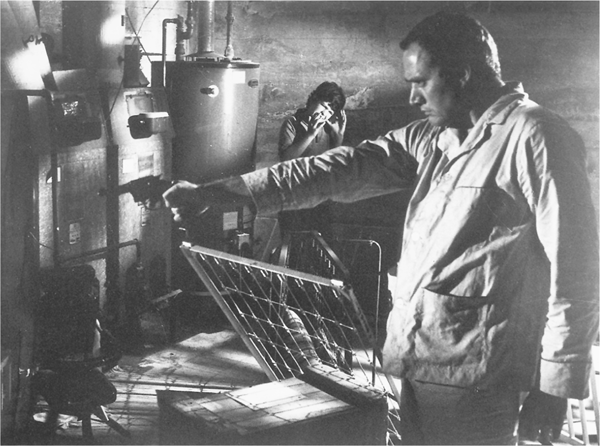

Father and Sons: John Ryan (right) in It’s Alive

I want to close this section by considering what seem to me Cohen’s most impressive films to date (one a horror film, the other not), which stand in one sense at opposite ends of the spectrum as, respectively, his least and most realized works: God Told Me To and The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover.

God Told Me To remains at once one of Cohen’s most fascinating works and incoherent to the point of unreadability. Again, part of the problem may be practical: the film’s ambitions palpably demanded a far higher budget and longer shooting schedule, a fact more obvious here than in any other of his works. Yet it is at the conceptual level that the film’s fascination and incoherence both lie. Indeed, it is organized (if that is the word) around the conflict between Cohen’s potential radicalism and his fundamental inability to trust it or commit himself to it: at least that is the only way I can make sense of any kind out of its dissonances and contradictions, the sense being a matter not of rendering the film coherent but of accounting for its incoherence. As it has had little exposure (either under its original title or its alternative title, Demon), I offer a brief plot summary.

A police detective (Tony Lo Bianco), reared a strict Catholic but with both a wife (Sandy Dennis) and a lover (Deborah Raffin), investigates a series of apparently random and motiveless killings by various assassins, tracing them to the inspiration of a young god, born of a human virgin impregnated by light from a spacecraft. He also discovers, however, that he is himself another such god, though in him the supernatural force has been repressed by his orthodox Catholic upbringing. He kills (or seems to kill) his unrepressed ‘brother’, and ends convicted of murder, repeating as an explanation of his motive the phrase used earlier by each of the assassins: “God Told Me To.”

The god is conceived as both beautiful and vicious. Like the snake of D. H. Lawrence’s famous poem, he is associated with danger, energy, and fire—with forces that society cannot encompass and therefore decrees must be destroyed. His disruption of the social order is arbitrary, involving a series of meaningless sniper-killings, the devastating of the St. Patrick’s Day Parade, and the annihilation of a family by its father; yet the imagery associated with him (the dance of light and flame) gives him stronger positive connotations than any other manifestation of the return of the repressed in Cohen’s work, or indeed in any other contemporary horror film.

Crucial to the film is the god’s dissolution of sexual differentiation: apparently male, he has a vagina, and invites the protagonist to father their child. The new world he envisages is, by implication, a world in which the division of sexual roles will cease to exist. What is proposed is no less than the overthrow of the entire structure of patriarchal ideology. The two god-inspired assassins whom the film presents in any detail are strongly characterized in terms of sexual ambiguity: the first (played by the actor who originated the role of the homosexual in A Chorus Line) is clearly meant to be taken as gay; the other (the young father who has murdered his wife and children) is also given culturally recognizable signifiers of gayness. Against all this is set the tangle and misery of the protagonist’s sexual life in Judeo-Christian culture, characterized by possessiveness, secrecy, deception, and denial. Significantly, what first arouses him to open violence is the young father’s sense of release and happiness after he has destroyed his family.

Like Cohen’s other films, God Told Me To proposes no solution. If its god was ever pure, his purity has been corrupted through incarnation in human flesh and the agents he is forced to use (the disciples are businessmen and bureaucrats, the possessed executants are merely destructive). Yet, unlike the use of Catholicism in The Exorcist, the restoration of repression at the end of the film is not allowed to carry any positive force, uplift, or satisfaction—only a wry irony. It is not even certain that the god is dead: the narrative says he is; the images, editing and implications question it. We last see him (after he appears to have been buried in the collapse of a derelict building) rising up in flames, his native element. Nothing clearly connects the protagonist to the god’s destruction, so we must assume that his conviction for murder rests on his own confession; we may infer that he has confessed in order to reassure himself that his antagonist-brother-double is really dead. In fact, the ending is left sufficiently open for one to wonder whether, had the film achieved any commercial success, Cohen would have written and directed a sequel to it rather than to It’s Alive. Certainly, the issues it opens up are both immense and profound, and absolutely central to our culture and its future development. Perhaps, instead of regretting the film’s confusion, we should celebrate its existence, the fact that Cohen had the audacity and partial freedom to imagine it at all.

The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover is perhaps the most intelligent film about American politics ever to come out of Hollywood. I cannot speak for its historical accuracy or for the justice of its speculative audacities: that Clyde Tolson was Deep Throat; that Hoover may have been implicated in the assassination of Bobby Kennedy—a possibility, the film, keeping just the safe side of libel, allows us to infer rather than states. But the film would be no less intelligent were its entire structure fictional. It is a question, not of whether what the spectator sees on the screen is “objective truth,” but of the relationship between the spectator and narrative.

The revealing comparison is with All the President’s Men. The overall effect of Alan Pakula’s film is complicated by the pervasive urban paranoia of film noir, a dominant element that makes the film’s relationship to Pakula’s The Parallax View less clearly one of simple contrast than the director seems to have intended. Nevertheless, it offers its audiences satisfactions that Cohen’s film rigorously eschews, notably in its suspense-thriller format and its hero identification figures. Hoover offers no equivalent for Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman; no heroes appear on whom we can rely to have everything put right at the end. No “correct” position is dramatized in the film with which the spectator might identify, by which he might be reassured. As there is no hero to uncover, be threatened by, and finally rectify the corruption, there can be no suspense, only analysis. Beside the obvious thriller brilliance of All the President’s Men, the sobriety and detachment of Hoover might be mistaken for flatness. In fact, the narrative’s ellipses and juxtapositions demand a continual activity on the part of the spectator, very different from, and incompatible with, the excitements of “What happens next?”

In the famous Cahiers du Cinéma analysis of Young Mr. Lincoln,1 the editors claimed that the film eventually produces Lincoln as a “monster,” both castrated and castrating. What is arguably implicit (or repressed) in John Ford’s film is the explicit subject of Cohen’s; applied to his Hoover, the Cahiers description is exact, word for word. Two points are made about the purity which Hoover attempts to bring to his work: that it is at all stages compromised by the corruptions of the system, and that it is itself artificial, an act of will growing out of a denial of the body. The film translates into overtly political terms the dialectic of its predecessors: neither the purity nor the corruption is sanctioned; they are presented as two aspects of the same sickness. As in It’s Alive, the monster is the logical product of the capitalist system.

Here, the “double” motif is made verbally explicit in the scene with Florence Hollister (Celeste Holm). Hoover has been responsible for the death of John Dillinger (whom he wanted to kill in person), and has since obsessively preserved his death mask and collected relics. Mrs. Hollister tells Hoover that he would secretly like to be Dillinger, and the context links this to Hoover’s sexual repression. Having destroyed Dillinger, Hoover has internalized his violence, converting it into a repressive, castrating morality.

Essential to the repression theme is the film’s treatment of Hoover’s alleged homosexuality and his relationship with Clyde Tolson The presentation of Hoover-as-monster rests on the notion that his repression is total, that he is incapable of acknowledging a sexual response to anyone, male or female. The desolate little scene where he sits, in semidarkness and longshot, listening to a tape of erotic loveplay of a politician he has bugged, suggests less a vicarious satisfaction than his sense of exclusion from an aspect of life as meaningless to him as a foreign language. Elsewhere, he can innocently reminisce about the time when Bobby Kennedy, as a child, sat on his lap and asked if he was “packing a gun”; for the audience, the line evokes Mae West, yet it is clear that for Hoover the obvious implication (that the boy’s proximity had given him an erection) simply does not exist.

The Tolson-Hoover relationship is treated with great delicacy and precision; out of it develops the film’s culminating irony. Hoover wants publicly to repudiate the press’s “slanders”; Tolson quietly advises him just to leave things alone. Tolson, in other words, is perfectly aware of what Hoover can never face: the real nature of their relationship. For a time it looks as if the film is going to produce Rip Torn as the politically aware (and heterosexual) hero who sets things right; but it is Tolson who acquires the private files, in his determination to vindicate his friend, after which the film is content enigmatically to inform us that Watergate happened a year later and Hoover couldn’t have done a better job.

The film’s point is that Watergate was made possible, not by the altruistic endeavors of a couple of heroic seekers after truth, but by the unfulfilled personal commitment of one man to another. Hoover’s one pure achievement, that is, grows inadvertently and apolitically, after his death, out of a relationship he could never even recognize for what it was. If the film celebrates anyone it is Tolson, but he is scarcely presented as any kind of answer. All the President’s Men communicates (at least on the surface level) that the System may be liable to corruption but will always right itself; Hoover views such a belief with extreme skepticism. It is scarcely surprising that, in Cohen’s own words, “We soon found ourselves besieged on all sides with no political group to spring to our defense.”

TESTING THE LIMITS

As a transition from Cohen to Romero I want briefly to consider three films—more than coincidentally, perhaps, they appeared within a year of each other, at that moment of ideological hesitation when the 70s became the 80s—that dramatize the essential dilemma of the horror genre. That dilemma, always present embryonically, only became manifest in the 70s, as the implications of the monster/normality dialectic became more and more explicit and inescapable. It can be expressed quite simply in a series of interrelated questions: Can the genre survive the recognition that the monster is its real hero? If the “return of the repressed” is conceived in positive terms, what happens to “horror”? And is such a positive conception logically possible? These questions are not trivial, and have ramifications far beyond the confines of a movie genre: the future of our civilization may depend upon the answer to the third.

The three films are Cohen’s It’s Alive II (It Lives Again), Romero’s Martin and John Badham’s Dracula. It is significant that all three are at once extremely interesting and extremely unsatisfactory, the interest lying in the ultimate failure as much as in the partial success. Each approaches the dilemma quite differently and attempts a quite different resolution, but they have certain basic characteristics in common. In all three, the audience is encouraged to hope for the monster’s survival and possible triumph; in all three, normality is subjected to astringent criticism, seen as characterized by repression, tension, and (especially in Martin) misery; in all three, this critique is centered on male/female relations and gender roles; in all three, the climactic horror is the destruction of the monster, presented as more appalling than anything the monster has done.

The problem with Martin is that it evades the dilemma rather than resolving it: Its eponymous hero isn’t really a monster, but a social misfit who has been led to believe he is a monster. One senses throughout the film a hesitation on Romero’s part as to whether he wanted to make a horror film at all. His essential theme—a downtrodden boy struggling to achieve a sense of identity and self-worth within a totally debased, repressive and drably materialistic social milieu—lends itself most obviously to the form of realist drama. The question is, I think, one of genuine hesitation rather than commercial compromise, Romero’s interest in the horror genre and his desire to extend its boundaries not being in doubt. The hesitation confuses the depiction of Martin himself and his relationship to Tata Cuda, the repressive father figure: Does his obsession with drinking blood represent the return of repressed energies, or is it merely a fantasy that has been imposed on him? The later stages of the narrative actually suggest that, by learning to have sexual intercourse instead of sucking blood, Martin can be “saved” for normality: we are not that far from the reductio ad absurdum enacted long before in House of Dracula, where the Wolf Man’s lycanthropy is cured by psychoanalysis and the love of a good woman (a more generous comparison would be with Chabrol’s Le Boucher). While normality has been demolished in the film with a ruthlessness rare in American commercial cinema, the energies that might overthrow or transcend it receive only the vaguest and most ambiguous embodiment: Martin’s fantasies are mere fantasies, carrying no positive connotations.

Reinterpreting the Vampire

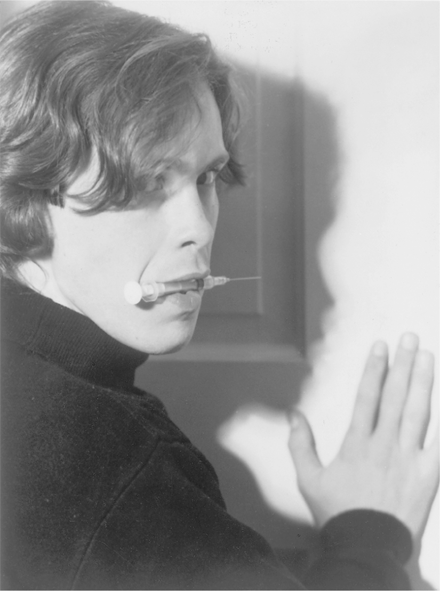

Frank Langella in Dracula

John Amplas in Martin

Where Martin reduces vampire mythology to a cloak, makeup and imitation fangs (“You see?—there is no magic”), Badham’s Dracula reverts to what is, as far as the cinema is concerned, its effective source in Bram Stoker’s novel, and attempts to transform its sense while retaining its potency. Badham’s movie has been gravely underestimated, by critics and public alike: in many ways it is quite remarkable, and as an interpretation of the novel extremely audacious. Sight and Sound, in one of its inimitable capsule reviews, went so far as to call it a straightforward adaptation than did not try to interpret, a startling critical aberration: For a start, this appears to be the first Dracula movie with a happy ending (of sorts), and the first in which it is van Helsing, not Dracula, who is transfixed through the heart with a stake (minor details which presumably escaped the Sight and Sound reviewer). Its key line is perhaps van Helsing’s earlier “If we are defeated, then there is no God”; they are defeated.

The film is very much preoccupied, in fact, with the overthrow of patriarchy, in the form of the Father, van Helsing, of whom God the Father is but an extension. The ending is not merely the triumph of Dracula (who, progressively undaunted by garlic and crucifixes in the course of the film, finally flies off, burned, battered, but still alive and strong, into the sunlight) but of Oedipus, who, having carried off the woman, kills the father and flies away. The film makes clear that Lucy is still his, even though she cannot join him until the hypothetical sequel (which, in view of the poor box office response, will now never get made). Indeed, the editing suggests quite strongly that it is Lucy who gives Dracula the strength to escape. It would be nice simply to welcome the film on those terms and leave it at that. Unfortunately, the matter is not so clear-cut, and the film seems to me, though very interesting and often moving, severely flawed, compromised and problematic. Its chief effect, perhaps, is to remind us that we live in an age, not of liberation, but of pseudo-liberation.

As in the original novel and its most distinguished cinematic adaptation, Murnau’s Nosferatu, the film’s problems are centered on the woman, Lucy (the superb Kate Nelligan), and on the difficulties of building a positive interpretation on foundations that obstinately retain many of their original connotations of evil. The result is a film both confused and confusing. In response to our popular contemporary notions of feminism, Lucy’s strength and activeness are strikingly emphasized and contrasted with Mina’s weakness, childishness and passivity. Dracula insists that Lucy come to him of her free choice: the film makes clear that he deliberately abstains from exerting any supernatural or hypnotic power over her, as he did over Mina. The film thus ties itself in knots in first presenting Lucy as a liberated woman and then asserting that a liberated woman would freely choose to surrender herself to (of all people) Dracula. Badham wants to present the Dracula/Lucy relationship in terms of romantic passion, a passion seen as transcending everyday existence; yet he cannot free the material of the paraphernalia of Dracula mythology, and with it the notion of vampirism as evil. With its romantic love scenes, on the one hand, and the imagery that associates both Dracula and Lucy with spiders, on the other, the film never resolves this contradiction.

Although it pays a lot of attention to the picturesque details of Victoriana, Badham’s movie seems far more Romantic than Victorian in feeling, and owes a lot to a tradition that has always had links with Dracula mythology: the tradition of l’amour fou and Surrealism. It is a tradition explicitly dedicated to liberation, but the liberation it offers; lacking any theories of feminism or bisexuality, proves usually to be very strongly male-centered, with an insistent emphasis on various forms of machismo. From Wuthering Heights through L’Age d’or to Badham’s Dracula, l’amour fou is characteristically built on male charisma to which the woman surrenders. The film’s emphasis on heterosexual romantic passion actually diminishes the potential for liberation implicit in the Dracula myth: the connotations of bisexuality implicit in the novel and developed in Murnau’s version are virtually eliminated (Dracula vampirizes Renfield purely to use him as a slave, not for pleasure, and he does so in the form of a bat; Jonathan’s visit to Transylvania is foregone, so there is no possibility of any equivalent of the castle scenes in Murnau); and the connotations of promiscuity are very much played down, with Dracula vampirizing other women almost contemptuously, his motivation centered on his passion for Lucy. Under cover of liberation, then, heterosexual monogamy is actually reinstated.

More sinister (though closely related) is the film’s latent Fascism. Dracula and Lucy are to be a new King and Queen; the “ordinary” people of the film—Jonathan and Mina, for example—are swept aside with a kind of brutal contempt. Between them, Dracula and Lucy will create a new race of superhumans who will dominate the earth. Dracula’s survival at the end—with Lucy’s complicity—is a personalized “triumph of the will,” the triumph of the superman over mere humans.

What Badham’s film finally proves—and it is a useful thing to have demonstrated—is that it is time for our culture to abandon Dracula and pass beyond him, relinquishing him to social history. The limits of profitable reinterpretation have been reached (as Frank Langella’s Dracula remarks, “I come from an old family—to live in a new house is impossible for me”). The Count has served his purpose by insisting that the repressed cannot be kept down, that it must always surface and strive to be recognized. But we cannot purge him of his association with evil—the evil that Victorian society projected onto sexuality and by which our contemporary notions of sexuality are still contaminated. If the return of the repressed is to be welcomed, then we must learn to represent it in forms other than that of an “undead” vampire-aristocrat.

It is characteristic of Cohen’s work in general that It’s Alive II should be at once the most careless and the most interesting of the three films. Martin and Dracula are, in their very different ways, closely worked; It’s Alive II looks hastily thrown together, another of Cohen’s rough drafts. The honesty, at once intuitive and intransigent, with which the concept is developed to the point where its inherent contradictions are exposed is also characteristic. The film develops explicitly what was already implicit in It’s Alive: that the monstrous babies, though extremely dangerous, may represent a new stage in evolution, may actually be superior to normal human beings. It then tries to operate according to a ‘double suspense’ mechanics: the babies threaten the sympathetic characters who, not without doubts and qualifications, are trying to protect them; the babies are threatened by the unsympathetic authority figures who, without considering the issues involved, want to destroy them. On the simplest level, the problem with the film (accounting no doubt for its commercial failure) is that the more sympathetic the babies become, the less frightening they are. At the same time they remain monstrous, grotesquely ugly (and we are allowed to see far more of them than in the original) and fundamentally inhuman; the visual conception totally lacks the fire-and-light connotations of the god of God Told Me To, along with the suggestions of a revolutionary sexuality. The babies’ superiority is also problematic, remaining a given rather than a concept that is explored and defined. They are telepathic, and develop very fast; they may have great intellectual potential. But these are fairly commonplace characteristics of monsters in the horror/science fiction genres (from “The Thing” to the “Midwich Cuckoos”): the notion that the babies may represent a valid human (or superhuman) future never becomes very compelling. The film is finally confused by Cohen’s recurrent preoccupation with biological parentage: the babies’ demand to be accepted into an impossible nuclear family, the inherent tensions and inequities of which the film has already thoroughly exposed, seems an intrinsically unprofitable line of narrative development. Yet if the film lacks the surface viability of Martin and Dracula, it reveals even more nakedly the intractability of the traditional monster/normality conflict for radical development beyond a certain point. For such a development to become possible, the conflict itself needs to be redefined, the monstrousness returned to the normality where it belongs. Such a strategy is apparent in the “living dead” films of Romero.

GEORGE ROMERO: Apocalypse Now

Night of the Living Dead (1968) and Dawn of the Dead (1979) represent the first two parts of a trilogy which Romero plans to complete later with Day of the Dead.2 They are among the most powerful, fascinating and complex of modern horror films, bearing a very interesting relationship both to the genre and to each other. What I want to examine here is their divergence: together, they demand a partial redefinition of the principles according to which the genre usually operates, and they are more distinct from each other—in character, tone and meaning—than has generally been noted (Dawn of the Dead is much more than the elaborate remake it has been taken for).

The differences—both from other horror films and between the two films—are centered on the zombies and their function in relation to the other characters. The zombies of Night answer partly to the definition of monster as the return of the repressed, but only partly: they lack one of the crucial defining characteristics, energy, and carry no positive connotations whatever. In Dawn, even this partial correspondence has almost entirely disappeared. On the other hand, the zombies of both films are not burdened with those actively negative connotations (“evil incarnate,” etc.) that define the reactionary horror film. The earlier films to which the living dead movies most significantly relate are both somewhat to one side of the main development of the horror film: The Birds (Night more than Dawn) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Dawn more than Night). The strategy that connects all four films (and at the same time distinguishes them from the most fully representative specimens of the genre) is that of depriving their monsters of positive or progressive potential in order to restore it to the human characters. From this viewpoint, Dawn of the Dead emerges as the most interesting of the four films (which is not to say that it is better—more complex, more suggestive, more intelligent—than The Birds).

Much has been made of the way in which Night of the Living Dead systematically undercuts generic conventions and the expectations they arouse: the woman who appears to be established as the heroine becomes virtually catatonic early in the film and remains so to the end; no love relationship develops between her and the hero. The young couple, whose survival as future nuclear family is generically guaranteed, is burned alive and eaten around the film’s midpoint. The film’s actual nuclear family is wiped out; the child (a figure hitherto sacrosanct—even in The Birds, which appeared the same year as Rosemary’s Baby, children sustain no more than superficial injuries) not only dies but comes back as a zombie, devours her father, and hacks her mother to death. In a final devastating stroke, the hero of the film and sole survivor of the zombies (among the major characters) is callously shot down by the sheriff’s posse, thrown on a bonfire, and burned.

But the film’s transgressions are not just against generic conventions: those conventions constitute an embodiment, in a skeletal and schematic form, of the dominant norms of our culture. The zombies of Night have their meaning defined fairly consistently in relation to the Family and the Couple. The film’s debt to The Birds goes beyond the obvious resemblances of situation and imagery (the besieged group in the boarded house, the zombies’ hands breaking through the barricades like the birds’ beaks). The zombies’ attacks, like those of the birds, have their origins in (are the physical projection of) psychic tensions that are the product of patriarchal male/female or familial relationships. This is established clearly in the opening scene. Brother and sister visit a remote country graveyard (over which flies the Stars and Stripes: the metaphor of America-as-graveyard is central to Romero’s work, the term “living dead” describing the society of Martin as aptly as it does the zombies). Their father is buried there, and the visit, a meaningless annual ritual performed to please their mother, is intensely resented—actively by the man, passively by the sullen woman. They take their familial resentments out on each other, as the film indicates they have always done; the man frightens his sister by pretending to be a monster, as he used to do when they were children; the first zombie then lurches forward from among the graves, attacks them both, and kills the man. At the film’s climax, when the zombies at last burst into the farmhouse, it is the brother who leads the attack on his sister, some obscure vestige of family feeling driving him forward to devour her.

In between, we have the film’s analysis of its typical American nuclear family. The father rages and blusters impotently, constantly reasserting a discredited authority (the film continually counterpoints the disintegration of the social microcosm, the patriarchal family, with the cultural disintegration of the nation, the collapse of confidence in authority on both the personal and political level). The mother, contemptuous of her husband yet trapped in the dominant societal patterns, does nothing but sulk and bitch. Their destruction at the hands of their zombie daughter represents the film’s judgment on them and the norm they embody.

The film has often been praised for never making an issue of its black hero’s color (it is nowhere alluded to, even implicitly). Yet it is not true that his color is arbitrary and without meaning: Romero uses it to signify his difference from the other characters, to set him apart from their norms. He alone has no ties—he remains unconnected to any of the others, and we learn nothing of his family or background. From this arises the significance of the two events at the end of the film: he survives the zombies, and he is shot down by the posse. It is the function of the posse to restore the social order that has been destroyed; the zombies represent the suppressed tensions and conflicts—the legacy of the past, of the patriarchal structuring of relationships, “dead” yet automatically continuing—which that order creates and on which it precariously rests.

Almost exactly halfway between the two living dead films, and closely related to both, is The Crazies, an ambitious and neglected work that demands parenthetical attention here for its confirmation of Romero’s thematic concerns and the particular emphasis it gives them: The pre-credits sequence is virtually a gloss on the opening of Night of the Living Dead, with brother and sister as young children and the acting out of tensions dramatized within the family. Again, brother teases sister by pretending to be a monster coming to kill her; abruptly, their “game” is disturbed by the father, the first “crazy” of the title, who has already murdered their mother and is now savagely destroying the house. The subsidiary family of the main body of the film (here father and daughter), instead of killing and devouring each other, act out the mutual incestuous desire on whose repression families are built. In general; however, the film moves out from Night’s concentration on the family unit into a more generalized treatment of social disintegration (a progression Dawn will complete).

The premise of the film is similar to that of Hawks’ Monkey Business (that the same premise can provide the basis for a crazy comedy and a horror movie is itself suggestive of the dangers of a rigid definition of genres, which are often structured on the same sets of ideological tensions): a virus in a town’s water supply turns people crazy, their craziness taking the form of the release of their precariously suppressed violence, its end result either death or incurable insanity. The continuity suggested by the opening between normality and craziness is sustained throughout the film; indeed, one of its most fascinating aspects is the way the boundary between the two is continually blurred. In the first part of the film after the declaration of martial law and the attempt to round up and isolate all the town’s inhabitants, the local priest finds his authority swept aside and the sanctuary of his church brutally repudiated. He becomes increasingly distraught, and publicly immolates himself. We never know whether he is a victim of the virus (acting, in his case, on a desire for martyrdom). Once such a doubt is implanted, uncertainty arises over what provokes the uncontrolled and violent behavior of virtually everyone in the film. The hysteria of the quarantined can be attributed equally to the spread of contagion among them or to their brutal and ignominious herding together in claustrophobically close quarters by the military; the various individual characters who overstep the bounds of recognizably normal behavior may simply be reacting to conditions of extreme stress. The crazies, in other words, represent merely an extension of normality, not its opposite. The spontaneous violence of the mad appears scarcely more grotesque than the organized violence of the authorities.

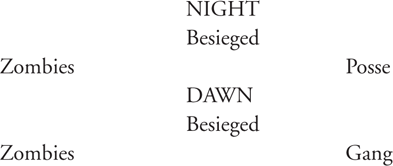

The end of Night of the Living Dead implies that the zombies have been contained and are in the process of being annihilated; by the end of Dawn of the Dead they have apparently overrun everything, and nothing remains but to flee. Yet Dawn (paradoxically, taking the cue from its title) comes across as by far the more optimistic of the two films. This is due partly to format (bright colors, as opposed to Night’s grainy and drab black and white), partly to setting (the garish and brilliantly lit shopping mall, contrasted with the shadowy, old-fashioned farmhouse), partly to tone (in Night, the zombies are never funny, the film’s black humor being mainly restricted to the casual brutalism of the sheriff’s posse). But these are only the outward signs of a difference which is basically conceptual. Both films are built upon all-against-all triangular structures, strikingly similar yet crucially different:

(The Crazies essentially repeats the pattern of Night, with crazies instead of zombies and the military substituting for the posse.)

The functions of the sheriff’s posse in Night and the motorcycle gang in Dawn are in some ways very similar. They constitute a threat both to the zombies and to the besieged (even if in Night inadvertently, by mistaking the hero for a zombie); more important, both dramatize, albeit in significantly different ways, the possibility of the development of Fascism out of breakdown and chaos. The difference is obvious: the purpose of the posse is to destroy the zombies and to restore the threatened social order; the purpose of the gang is simply to exploit and profit from that order’s disintegration. The posse ends triumphant, the gang is wiped out.

The premise of Dawn in fact is that the social order (regarded as in all Romero’s films as obsolete and discredited) can’t be restored; its restoration at the end of Night simply clinches the earlier film’s total negativity. The notion of social apocalypse is succinctly established in Dawn’s TV studio prologue: television, the only surviving medium of national communication whereby social order might be maintained, is on the verge of closing down; as a technician tells Fran, “Our responsibility is at an end.” The characters of Night were still locked in their responsibility to the value structure of the past; the characters of Dawn are at the outset absolved from that responsibility—they are potentially free people, with new responsibilities of choice and self-determination. Since the zombies’ significance in both films depends entirely on their relationship to the main characters, it follows that their function here is somewhat different. They are no longer associated with specific characters or character tensions, and the family as a social unit no longer exists (it is only reconstituted in parody, when the injured Roger becomes the-baby-in-the-pram, wheeled around the supermarket by his “parents” as he shoots down zombies with childish glee). The zombies instead are a given from the outset; they represent, on the metaphorical level, the whole dead weight of patriarchal consumer capitalism, from whose habits of behavior and desire not even Hare Krishnas and nuns, mindlessly joining the conditioned gravitation to the shopping mall, are exempt.

As in The Crazies, the seemingly clear-cut distinctions between the three groups are progressively undermined (aside from the obvious visual differentiation between zombies and humans). The motorcycle gang’s mindless delight in violence and slaughter is anticipated in the development of Roger; all three groups are contaminated and motivated by consumer greed, which the zombies simply carry to its logical conclusion by consuming people. All three groups, in other words, share a common conditioning: all are predators. The substance of the film concerns the four characters’ varying degrees of recognition of, and varying reactions to, this fact. Two become zombies, two (provisionally) escape.

Lover as Zombie: David Emge in Dawn of the Dead

In place of Night’s dissection of the family, Dawn explores (and explodes) the two dominant couple relationships of our culture and its cinema: the heterosexual couple (moving inevitably toward marriage and its traditional male/female roles) and the male “buddy” relationship with its evasive denial of sexuality (the pattern is anticipated in the central triangle relationship of the three principles of The Crazies). Through the realization of the ultimate consumer society dream (the ready availability of every luxury, emblem, and status symbol of capitalist life, without the penalty of payment) the anomalies and imbalances of human relationships under capitalism are exposed. With the defining motive—the drive to acquire and possess money, the identification of money with power—removed, the whole structure of traditional relationships, based on patterns of dominance and dependence, begins to crumble.

The heterosexual couple (an embryonic family, as Fran is pregnant) begins as a trendy variation on the norm: they are not legally married, and the woman is allowed a semblance of independence through her career; but as soon as the two are together the conventional assumptions operate. It is the man who flies the helicopter and carries the gun—the film’s major emblems of sexual/patriarchal authority. At various points in the narrative Fran nostalgically re-enacts the role of female stereotype, making up her face as a doll-like image for the male gaze, skating alone on the huge ice rink—woman as spectacle, without an audience. But in the course of the film she progressively assumes a genuine autonomy, asserting herself against the men, insisting on possession of a gun, demanding to learn to pilot the machine. The pivotal scene is the parody of a romantic dinner with flowers and candlelight—the white couple in evening dress cooked for and waited on by the black—with the scene building to the man’s offer and the woman’s refusal of the rings that signify traditional union.

The closest link between Night and Dawn is the carry-over of the black protagonist, his color used again to indicate his separation from the norms of white-dominated society and his partial exemption from its constraints. Through the developing mutual attachment between him and Roger, the film takes up and comments on the buddy relationship of countless recent Hollywood movies and its implicit sexual undercurrents and ambiguities. Neither man shows any sexual interest in the woman, yet both are blocked by their conditioning from admitting to any in each other. Hence the channeling of Roger’s energies into violence and aggression, his uncontrolled zest in slaughter presented as a display for his friend. The true nature of the relationship can be tacitly acknowledged only after Roger’s death, in the symbolic orgasm of the spurting of a champagne bottle over his grave.

Both the film’s central relationships are broken by the death of one of the partners. The two who die are those who cannot escape the constraints of their conditioning, the survivors those who show themselves capable of autonomy and self-awareness. The film eschews any hint of a traditional happy ending, there being no suggestion of any romantic attachment developing between the survivors. Instead of the restoration of conventional relationship patterns, we have the woman piloting the helicopter as the man relinquishes his rifle to the zombies. They have not come very far, and the film’s conclusion rewards them with no more than a provisional and temporary respite: enough gasoline for four hours, and no certainty of destination. Yet the effect of the ending is curiously exhilarating. Hitherto, the modern horror film has invariably moved toward either the restoration of the traditional order or the expression of despair (in Night, both). Dawn is perhaps the first horror film to suggest—albeit very tentatively—the possibility of moving beyond apocalypse. It brings its two surviving protagonists to the point where the work of creating the norms for a new social order, a new structure of relationships, can begin—a context in which the presence of a third survivor, Fran’s unborn child, points the way to potential change. Romero has set himself a formidable challenge, and it will be interesting to see how the third part of the trilogy confronts it.

NEGLECTED NIGHTMARES

Romero’s work represents the most progressive potentialities of the horror film, the possibility of breaking the impasse of the monster/normality relationship developed out of the Gothic tradition. But the final emphasis here must be on the genre rather than on the work of an individual director, for it is the vitality of the genre itself—fed, in the 70s, by the whole pervasive sense of ideological crisis and imminent collapse—that is so remarkable in this period. I want to end, then, by examining a handful of neglected (in some cases virtually unknown) films by directors either not particularly associated with the horror film (Stephanie Rothman), or whose careers have proved subsequently disappointing (Wes Craven, Bob Clark).

If I begin with Craven’s Last House on the Left it is partly because it has achieved at least a certain underground notoriety; it surfaced briefly in the pages of Film Comment (July-August 1978) as one of Roger Ebert’s Guilty Pleasures. I had better say that the Guilty Pleasures feature seems to me an entirely deplorable institution. If one feels guilt at pleasure, isn’t one bound to renounce either one or the other? Preferably, in most cases, the guilt, which is merely the product of that bourgeois elitism that continues to vitiate so much criticism. The attitude fostered is essentially evasive (including self-evasive) and anti-critical: “Isn’t this muck—to which of course I’m really so superior—delicious?”

Ebert’s Guilty Pleasures (which may be Last House’s only recognition so far by a professedly serious critic) is brief enough to quote in full:

The original Keep repeating—It’s Only a Movie!!! movie. The plot may sound strangely familiar. Two young virgins go for a walk in the woods. One is set upon by vagabonds who rape and kill her. The other escapes. The vagabonds take their young victim’s clothes and set on through the wood, coming at last, without realizing it, to the house of the victim’s parents. The father finds his daughter’s bloodstained garments, realizes that he houses the murderers, and kills them by electrifying the screen door and taunting them to run at it, whereupon they slip on the shaving cream he’s spread on the floor, fall into the screen, and are electrocuted.

Change a few trifling details (like shaving cream) and you’ve got Bergman’s Virgin Spring. The movie’s an almost scene-by-scene ripoff of Bergman’s plot. It’s also a neglected American horror exploitation masterpiece on a par with Night of the Living Dead. As a plastic Hollywood movie, the remake would almost certainly have failed. But its very artlessness, its blunt force, makes it work.

Pleasure or not, Ebert has plenty here to feel guilty about:

1. The virginity of one of the girls (Phyllis) is very much in question. The relationship between them is built on the experienced/innocent opposition (as in Bergman’s original, the plot of which, by the way, was also a “scene-by-scene rip-off” of a medieval ballad), though the innocence of Mary (the nice bourgeois family’s daughter) is also questioned: she is a flower child with an ambiguous attraction to violence.

2. The girls meet the “vagabonds” in the latter’s apartment in the city: they are on their way to a concert by a rock group noted for its onstage violence, and pause to try to buy some dope from the youngest of the gang, who is lounging about on the front steps.

3. Ebert is decently reticent about the “vagabonds” (their background, relationships, sex, and even their number). His association of them with “the wood” deprives them of the very specific social context that Craven in fact gave them. There are four: as escaped killer, his sadistic friend Weasel, their girl Sadie, and the killer’s illegitimate teenage son Junior.

4. I am not clear which girl Ebert thinks “escapes.” Phyllis gets away briefly but is soon recaptured, tormented, repeatedly stabbed, and (in the original, though Craven himself wonders if a print survives anywhere with this included) virtually disemboweled. The abridged version leaves no doubt that she is dead. Mary staggers into the water to cleanse herself after she is raped, and is repeatedly shot; her parents later find her on the bank, and she dies in their arms.

5. The “vagabonds” do not take Mary’s clothes. Her body, which they presume dead, is drifting out in the middle of a large pond. The mother (as in Bergman), searching the men’s luggage after overhearing some semi-incriminating dialogue and one of the gang calling out in his sleep, finds the peace pendant her husband gave Mary at the start of the film, and blood on the men’s clothes.

6. No one in the film dies from electrocution. The father spreads shaving cream outside the upstairs bedroom door to slow his victims down, and electrifies the screen door to prevent their escaping by it. The gang are disposed of as follows: the nice bourgeois mother seduces Weasel out in the dark by the pond where Mary was raped, fellates him, and bites off his cock as he comes; the killer contemptuously persuades his son Junior to blow out his own brains; the mother cuts Sadie’s throat outside in an ornamental pond while her husband dispatches Junior’s father with a chain saw—presumably decapitating him, and thereby completing the parallel between the simultaneous actions (though this is about the only thing that Craven doesn’t show).

That Ebert’s plot synopsis sets a new record in critical inaccuracy (combined with characteristic critic-as-superstar complacency) says less about him personally than about a general ambiance that encourages opinion-mongering, gossip, Guilty Pleasures, and similar smart-assery—and, as an inevitable corollary, actively discourages criticism and scholarship. What does it matter whether he gets the plot right or not? Hell, it’s only a movie, and an exploitation movie at that, albeit an “American horror exploitation masterpiece on a par with Night of the Living Dead,” which Ebert mercilessly slammed when it came out. (Is this supposed to be his public retraction?)

What I mean by bourgeois elitism could as well be illustrated from the writings of John Simon or Pauline Kael. What the critic demands, as at least a precondition to according a film serious attention, is not so much evidence of a genuine creative impulse (which can be individual or collective, and can manifest itself through any format) as a set of external signifiers that advertise the film as a Work of Art. No one feels guilty about seriously discussing The Virgin Spring, though the nature of Bergman’s creative involvement there seems rather more suspect than is the case with Last House. What is at stake, then, is not merely the evaluation of one movie but quite fundamental critical (hence cultural, social, political) principles—issues that involve the relationship between critic and reader as well as that between film and spectator.

The relationship of Last House to The Virgin Spring is not, in fact, close enough to repay any detailed scrutiny, though one might remark that, if the term “rip-off” is appropriate here, it is equally appropriate to the whole of Shakespeare, the debt being one of plot outline and no more. The major narrative alterations—the transformation of Ingeri into Phyllis and of the child goat-herd into the teenage Junior, the killing of both girls, the addition of Sadie, the mother’s active participation in the revenge, the destruction of Junior by his own father—are all thoroughly motivated and in themselves indicate the creative intelligence at work.

The most important narrative change is that of overall direction and final outcome. Bergman’s virgin is on her way to church, and the film leads to the somewhat willed catharsis of her father’s promise to build a new church, and the “answer” of a spurious and perfunctory miracle. Craven’s virgin is on her way to a rock concert by a group that kills chickens on stage and, as the recurrent pop song on the sound-track informs us, “the road leads to nowhere.” The last image is of the parents, collapsed together in empty victory, drenched in blood.

But the crucial difference is in the film-spectator relationship, especially with reference to the presentation of violence. Joseph Losey saw Bergman’s film as “Brechtian,” but I think its character is determined more by personal temperament than aesthetic theory: the ability to describe coldly and accurately, without empathy—or, perhaps more precisely, with an empathy that has been repressed and disowned. If there is something distasteful in the film’s detailing of rape and carnage, it is because Bergman seems to deny his involvement without annihilating it, and to communicate that position to the spectator.

The Virgin Spring is Art; Last House is Exploitation. One must return to that dichotomy because the difference between the two films in terms of the relationship set up between audience and action is inevitably bound up with it. I use the terms Art and Exploitation here not evaluatively, but to indicate two sets of signifiers—operating both within the films as “style” and outside them as publicity, distribution, etc.—that define the audience-film relationship in general terms. As media for communication, both Art and Exploitation have their limitations, defined in both cases, though in very different ways, by their inscriptions within the class system. Both permit the spectator a form of insulation from the work and its implications—Art by defining seriousness in aesthetic terms implying class superiority (only the person of education and refinement can appreciate Art, i.e., respond to that particular set of signifiers), Exploitation by denying seriousness altogether. It is the work of the best movies in either medium to transcend or transgress these limitations, to break through the spectator’s insulation.

In organizing a horror film retrospective for the 1979 Toronto film festival, Richard Lippe and I also set out to transgress. We wanted (through the accompanying booklet and the directors’ seminars, which only a very small proportion of our audience attended) to cut through the barriers bourgeois society erects as protection against the genre’s implications—defenses that take many forms: laughter, contemptuous dismissal, the term “schlock,” the phenomenon of the late-night horror show, the treatment of the horror film as Camp. In a way, Last House succeeded where we failed. A number of our customers—even in the context of a horror retrospective, even confronted by a somewhat bowdlerized print—gathered in the foyer after the screening to complain to the theater management that the film had been shown at all. Clearly, the film offers a very disturbing experience, its distinction lying in both the degree and nature of the disturbance. It is essential to this that its creation was a disturbing experience for Craven himself, a gentle, troubled, quiet-spoken ex-professor of English literature. The exploitation format and the request from the producer to “do a really violent film for $50,000” seem to have led him to discover things in himself he scarcely knew were there, which is also the effect it has on audiences. As Craven said:

I found that I had never written anything like this, and I’d been writing for ten to twelve years already. I’d always written artistic, poetic things. Suddenly, I was working in an area I had never really confronted before. It was almost like doing a pornographic film if you’d been a fundamentalist. And I found that I was writing about things that I had very strong feelings about. I was drawing on things from very early in my own childhood, things that I was feeling about the war, and they were pouring into this very simple B-movie plot.

That extraordinary linking of “things from very early in my childhood” to “things that I was feeling about the war” is the kind of central perception about a film that criticism strives for and often misses. The connection between Vietnam and the fundamental structures of patriarchal culture is one I shall return to in discussing The Night Walk.

The reason people find the violence in Last House so disturbing is not simply that there is so much of it, nor even that it is so relentlessly close and immediate in presentation. (Many, myself included, have come to praise films for being “Brechtian,” but it should also be acknowledged that distanciation is not the only valid aesthetic method.) I want to draw here on ideas derived from an admirable book, Violence in the Arts by John Fraser. The book is one of the rare treatments of this subject that manages to be intelligent and responsible without ever lapsing into puritanism, hypocrisy, or complacency. Its weakness is, I think, a failure to argue clearly as to whether violence is innate in “the human condition,” a product of specific social structures, or a combination of the two—to speculate, that is, on the degree to which violence would disappear within a truly liberated society.

Violence, whether actual or implicit, is so powerfully and obstinately inherent in human relationships as we know them (structured as they are on dominance and inequality) that the right to a pure denunciation of it must be a hard-won and precarious achievement. It is difficult to point to such an achievement in the cinema: perhaps Mizoguchi (the brandings and cutting of the tendon in Sansho the Bailiff), perhaps Fritz Lang (the scalding of Gloria Grahame in The Big Heat—but even there, what feelings are aroused by her eventual retaliation?) As for myself, I am a committed pacifist who has experienced very strong desires to smash people’s faces in, and who can remember incidents when I joined in the persecution of those in an inferior position and took pleasure from it; I have also, not infrequently, been a victim, and my greatest dread is of total helplessness at the mercy of tormentors. It is these three positions—the position of victim, the position of violator, the position of righteous avenger—and the interconnections among them that Last House on the Left dramatizes. Its distinction lies in the complex pattern of empathies that it creates.