I want to discuss My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997) in relation to three associated topics: its relation to classic screwball comedy and the other recent attempts to rethink that genre in contemporary terms; its auteurist relationship with Muriel’s Wedding (1994); and the current widespread use of gay characters in contemporary comedies. As this chapter will accordingly be more “around” than “on,” I had better begin by saying plainly that I love the film: if not “profound” or in any of the more obvious ways “groundbreaking,” it seems to me a flawless and progressive example of its genre, giving continuous delight over many re-viewings.

SCREWBALL ANCIENT AND MODERN

We all recognize certain films as “screwball,” yet the term requires definition; the simplest way to define it is to situate it between the “romantic” comedy and the “crazy” or “slapstick” comedy, as it clearly relates to both while remaining distinct from either, its distinctness arising perhaps from the ways in which it borrows and combines elements from each. McCarey provides the ideal touchstones, as he produced outstanding examples of all three categories: Duck Soup, the ideal crazy comedy; Love Affair or its remake An Affair to Remember, the ideal romantic; and The Awful Truth, among the greatest screwballs.

At the heart of both “screwball” and “romantic” is the romantic couple, generally absent from or marginal to “crazy.” (Although Chaplin and Lloyd always had romantic “interests,” their films are celebrated primarily for the comedians’ performances, set pieces, and skills; although Laurel and Hardy might at a stretch be seen as a romantic couple, the stretch would be a very long one; and I don’t think anyone would label the various courtships of Groucho and Margaret Dumont “romantic” exactly.) This is why the distinction is not always clear-cut. A rough but sufficiently accurate way of putting it might suggest that the romantic comedy is primarily about the construction of the ideal romantic couple, while the screwball comedy is primarily about liberation (and the couple it constructs is often very short of the romantic ideal—see, for example, Bringing Up Baby or The Lady Eve—or Too Many Husbands, which audaciously constructs a threesome): the overthrow of social convention, of bourgeois notions of respectability, of traditional gender roles. (The resolution of My Best Friend’s Wedding is already clearly in view and might be claimed as the genre’s logical “happy end,” which has only in very recent years become possible within the constraints of Hollywood cinema.) This is precisely where “screwball” links to “crazy”—to the anarchy of the Marx Brothers, or the (often inadvertent) destruction of social norms, homes, and property in Laurel and Hardy: plausibility is much less an issue in “screwball” than in “romantic.” The Awful Truth might be taken as the perfect midpoint between the two, “crazy” and “romantic” held meticulously in balance.

The most interesting aspect of this movement toward liberation, the overthrow of norms, is the recurrent emphasis in screwball (the theme, one might claim, of the best screwballs) on the emancipation and empowerment of women. Hence The Awful Truth is essentially about (in Andrew Britton’s words) “the chastisement of male presumption”1 and the progress of the couple toward equality. The most extreme instance—hence the closest of all the screwballs to “crazy”—is of course Bringing Up Baby, single-mindedly concerned with Cary Grant’s liberation at the merciless hands of Katharine Hepburn, and culminating with faultless logic in that still potent image of the overthrow of patriarchy, the collapse of the dinosaur skeleton into “nothing but a heap of old bones,” to misquote Hepburn from earlier in the film. Other notable examples: The Lady Eve, Two-Faced Woman (the original version, not the bowdlerized horror currently available on video—see Richard Lippe on this in CineAction 35), and (on a lower level of achievement) Theodora Goes Wild and Too Many Husbands, in which Jean Arthur, despite having been compelled by the patriarchal legal system to choose between Fred MacMurray and Melvyn Douglas, ends up keeping them both. From this viewpoint, these films are more progressive, subversive, and potentially revolutionary than almost anything Hollywood is turning out today. This becomes particularly clear when one considers a more recent attempt at screwball that most obviously corresponds to the classic model: Forces of Nature (1999), where the model is patently Bringing Up Baby. The film was generally attacked (reasonably enough) for its ineptness and the actors’ total lack of chemistry or charisma, but its real crime is the betrayal of its Hawksian forerunner: instead of progressing toward liberation, its characters simply learn to be older and wiser, a condition which presumably renders liberation superfluous.

Screwball comedies are no longer concerned with women’s empowerment, following the widespread social assumption that women don’t need to be empowered any more, they’ve won all their battles and they’re empowered quite sufficiently, thank you. Meanwhile, I open my newspaper every morning to read about all the battered, raped and/or murdered women who have been battered, raped, and murdered by men, most commonly their husbands or male lovers; about all the single mothers struggling in poverty, driven up to or over the brink of homelessness; the closing of women’s shelters and of day care centers following the withdrawal of government funding; the struggles of women to secure tenured positions or promotion in universities, and their struggle everywhere to secure equal pay for equal work; their virtual exclusion from the upper echelons of male-controlled capitalism, unless they are committed to supporting the further empowerment of men; or, conversely, the enormously greater number of female secretaries, servants, housecleaners than male. The only contemporary screwball comedy to treat this subject responsibly has been generally ignored: The Associate (1996), flawed by faulty construction and indifferent direction but distinguished by splendid performances by Whoopi Goldberg and Dianne Wiest. The film’s attack on the subordination and exploitation of women (and of blacks) within the overwhelmingly white-male-dominated structures of our financial institutions and corporations is crude but devastating.

Yet, if the great underlying subject of classic screwball has now been declared officially obsolete by the current capitalist/patriarchal conspiracy, the genre itself has, by a process of mutation, at its best replaced it with other concerns apparently distinct from it yet clearly relevant to it: the assault on the traditional bastions of marriage, family, biological parentage, sexuality, and gender. If the problems of women are now officially “solved,” then the problems that are so intimately and intricately involved in women’s continuing oppression—indeed, they form its basis—are now being exposed to criticism as never before. I have particularly in mind Flirting with Disaster (1996), The Daytrippers (1996), and My Best Friend’s Wedding.

Our civilization has come a long way since the great days of screwball—a long way toward potential and perhaps imminent cataclysm: we have had World War II, the threat of nuclear annihilation, and the devastation of the environment by the joint (if contending) forces of advanced capitalism—not only in the countries of the West but now also in former Soviet Russia and even in Communist China—with the apparently insatiable greed of those who believe that the possession of vast hoards of money by a few justifies the social misery of millions and the possible end of life on the planet. Accordingly, civilization’s basic structures—social, political, ideological—and the structures of social/sexual organization that are at once their product and sustenance are provoking increasingly greater anxiety, discontent, disturbance: it cannot be stressed too often (as so few appear to listen) that there is a clear and logical connection between the patriarchal nuclear family and the dominant socioeconomic/political structures. Given capitalism’s continuing power, especially its power to keep its populations in a condition of chronic mystification through the media it essentially controls, this disturbance crystallizes into fully conscious opposition only among a small minority; but the inchoate sense of dissatisfaction is by now virtually all-pervasive, especially among the younger generations. Because the dissatisfaction can’t be consciously formulated, it expresses itself only in cynicism and impotent forms of rebellion. Yet the disillusionment with our traditional, fundamental institutions—marriage and family, the organization of gender and sexuality—is discernible everywhere. It structures the best contemporary screwball comedies as surely as the empowerment of women structured the classics of the 1930s and 40s.

The most complete and rigorous working through of this is clearly The Daytrippers, perhaps the most shockingly neglected American film of the past decade, little known, seldom screened, currently accessible only on a “formatted to fit your TV screen” video and a DVD that does nothing to remedy this. Never screwball, and by its end no longer even a comedy, it nonetheless has an archetypal screwball premise and narrative structure: wife, after tender and affectionate early morning scene with husband, sees him off to his office, then finds (while doing the housework) a love note signed “Sandy” under the bed. Distraught, she enlists the aid of her mother, who in turn enlists father, younger sister, and younger sister’s fiancé for a trip into the city to confront the errant husband en masse. One can even imagine how this might have been cast, in the heyday of screwball in its more conservative “family” mode: William Powell as the husband, Myrna Loy or Irene Dunne as the wife, Mary Boland and Charlie Ruggles as the parents, Ann Rutherford as the younger sister … There would have been a series of hilarious misadventures; the husband, finally tracked down, would explain that “it was all a mistake”; and familial and conjugal solidarity would be restored, confirmed by the promise of the younger couple’s imminent wedding. The Daytrippers systematically reverses this pattern: the journey, starting in early morning, ending in very late night, is a steady progress into darkness and disintegration. By the end, both the marriage and the engagement have broken up, the family has fallen irremediably apart, and the two sisters walk off together into the night. As usual with American narrative movies, all this allows itself to be read in purely individual terms (this particular marriage, this family, etc.), but it in no way forbids a symbolic reading, as a “fable for our time” (the family is clearly presented as “typical”). Perhaps the reason why it is the most radical of current screwball (or screwball-derived) comedies is because it is the furthest from its models, in tone and narrative progression.

My Best Friend’s Wedding is obviously more lightweight, truer to the screwball spirit. But beneath its more frivolous, less openly subversive, surface it relates clearly enough to the same tendencies.

WHAT My Best Friend’s Wedding HAS IN COMMON WITH Muriel’s

Muriel’s Wedding was both written and directed by P. J. Hogan; on My Best Friend’s Wedding he has only the director’s credit. I have no information on why exactly he was invited to Hollywood (though obviously the critical and popular success of the Australian film had a great deal to do with it), or on how he came to direct the film he did: was it his choice (from a range of possible screenplays or subjects offered), was it chosen for him as some kind of specialist in weddings, to what extent did he control or contribute to the evolution of the final screenplay? If the finished screenplay was simply handed to him with a “Direct this,” then we are dealing with a most remarkable coincidence: despite their enormous differences (in tone, milieu, characterization), the structures of the two films reveal striking similarities. The differences can be accounted for by the change in national and social milieu and the different possibilities offered by the American and Australian cinemas and their very divergent inflections of the comic genre. At risk of treading upon sensitive nationalist toes, I have to say that most of the Australian films (or films set and shot in Australia) I’ve seen come across as terrible warnings: “Never, never emigrate to Australia. Don’t even contemplate it. At best you’ll be screamed at and victimized, and at worst forcibly sodomized by Donald Pleasance.” (Let me add that I could say much the same about the cinema of my own home country, England.) The contrast between the sophistication and nuance of My Best Friend’s Wedding and the in-your-face crudity of its predecessor are impossible to account for in terms simply of authorial sensibility—though in the case of the American film this must be attributed to the influence of genre rather than to anything discernible in the contemporary Hollywood scene.

The trajectory common to both films can be summed up as follows: a woman becomes obsessed (for quite different reasons) with a particular wedding, real or fantasized (her own purely hypothetical one—Muriel/Toni Collette—and that of the man she has suddenly realized she loves—Julianne or “Jules”/Julia Roberts). In both cases, though, the woman wants the wedding to be her own—for Muriel it is a status symbol that will at last gain her some respect; for Jules the means of possessing the man she loves, colored by the even more ignoble desire to get her own way, her behavior at times suggesting that of the little girl who stamps her foot and cries “I want it!!! I want it!!!” Each female protagonist is obsessed with a particular song that offers her a fantasy image of herself: Abba’s “Dancing Queen” for Muriel, “Just the Way You Look Tonight” for Jules; and in both films the song returns in the final sequences as a signifier of her liberation from obsession. In both films the woman’s obsessiveness drives her increasingly into selfish and irresponsible behavior that takes no account of other people’s feelings and which she ultimately recognizes as a betrayal of her own finer ones. The wedding brings disillusionment and with it liberation: she begins to look at herself and examine her behavior, and to free herself of her obsession. Most remarkable is the congruence of the endings: both films end with the heroine reunited with the character who has come to represent her conscience, but who also, significantly, is an outsider-figure, set apart by a marked “difference,” with whom she appears to be cementing a permanent relationship but whom she cannot possibly marry, and whose personal situation (crippled, gay) places both in a position where they can view the social milieu, its traditions and behavior patterns, objectively and critically. One might say that they are presented as the most admirable characters of their respective films precisely because they can’t marry—can’t, that is, participate in their culture’s central principle of organization.

The films share an extremely jaundiced view of weddings and their function, and beyond that, implicitly, of marriage. This is expressed quite blatantly in Muriel, and is somewhat gentler and more circumspect in Best Friend, where the tone is established at the outset by that charming, hilarious, satirical credit sequence. Our confidence in the Dermot Mulroney/Cameron Diaz marriage is subtly but thoroughly undermined: the pair are obviously mismatched, their interests totally incompatible (reminiscent, in fact, of Stewart and Kelly in Rear Window!) in the archetypal manner of our culture, (male) adventurer versus (female) settler. Jules is able to undermine their apparent stability at first serious attempt, the instant quarrel she negotiates only resolved by the woman’s instant and total capitulation to the man’s needs. And the central sequence on the sightseeing launch makes it clear that the prospective groom’s attachment to Jules remains considerably more than friendly and can be reignited quite easily. In view of this the film’s final celebration of the traditional couple, as they depart for their honeymoon with the aid of romantic music, slow motion, confetti, and sudden gushing fountains, must be read as part-ironic, part an aspect of the film’s generosity, a tribute to the essential niceness and excellent intentions of its characters: the effect might be summed up as “You haven’t a hope but we wish you well.”

PERFORMANCE/STRUCTURE

Though generally liked, My Best Friend’s Wedding has not received anything like the recognition it deserves. It is one of the great American comedies, comparable in its perfection with the finest “classic” screwballs, perfectly written, perfectly cast, perfectly acted, perfectly directed. I have watched it at least half a dozen times, replaying whole sequences for the sheer pleasure of the nuances of timing and the ensemble playing. It is continuously alive, down to the smallest detail: when one has watched (for example) the scene in the karaoke bar, or the sequence of the eve-of-wedding luncheon party, a few times, one suddenly begins to notice the extras: there is no “dead” space on the screen; every visible extra in the crowded bar or restaurant is caught up in the overall performance. The four principals are beyond praise. If Roberts and Rupert Everett strike one most immediately, that is because they have the showiest roles; but their performances are matched by those of Diaz and Mulroney.

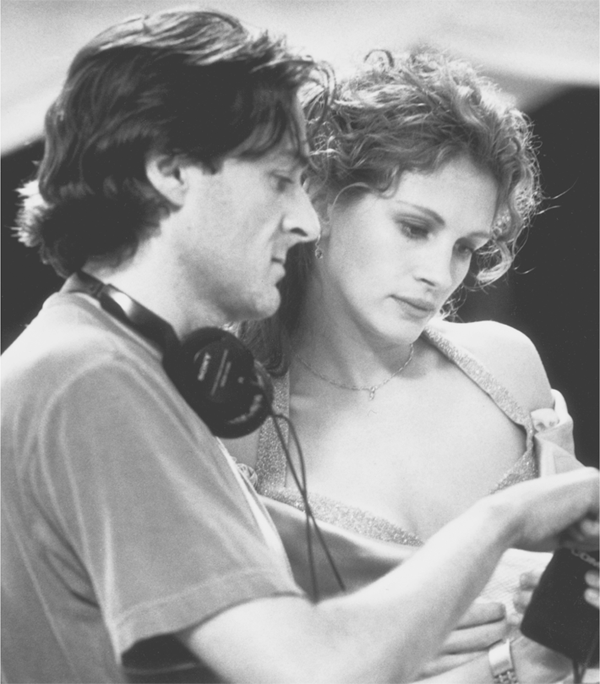

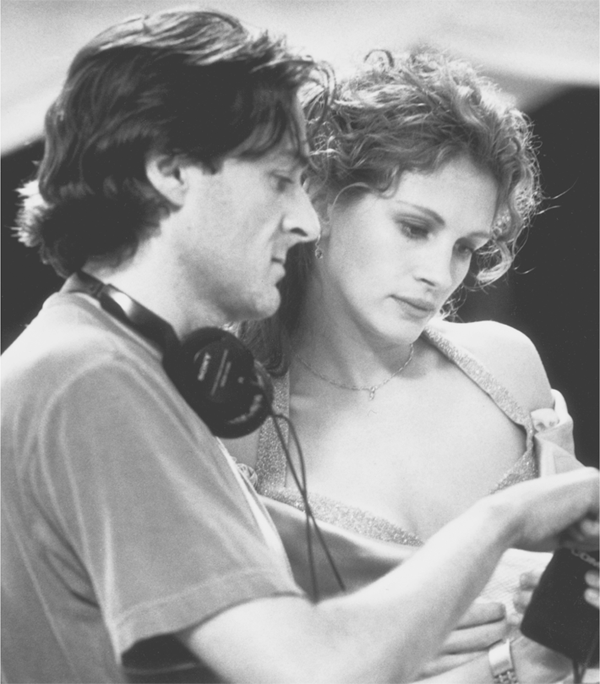

My Best Friend’s Wedding: Director and star discuss a scene

The film is built upon a dual structure: the shifting and evolving relationships between Julianne and the two men in her life, Michael (Mulroney) and George (Everett). Both relationships are introduced, with great economy, at the outset: Julianne, a prestigious food columnist and critic, is dining out with George, her editor (the “date” combines work and pleasure, as she is reviewing the restaurant); during the meal she checks her messages on her cell phone and receives the urgent communication from Michael (she is to call him back, any time, even in the middle of the night) that precipitates the entire action. Michael is her “best friend,” with whom she once had a brief romantic fling; when they broke it off they swore to marry each other if they hadn’t found a partner by the age of twenty-eight. Both will be twenty-eight within weeks; it is George who initially puts into her head the notion that a wedding with her “best friend” is on the horizon.

The film plays throughout on the “best friend” motif. When Kimmy (Diaz) asks Julianne to be her maid of honor, she adds: “This means I have four days to make you my best friend” (Julianne has the same four days to break up the wedding). At the ballpark, when Michael first begins to see Julianne in a new light, he asks her: “What did you do with my best friend?” At the tailor’s, when Michael is being fitted for his suit, Julianne introduces George as “my good friend … my best friend these days.” George has already replaced Michael as Julianne’s best friend; at the film’s extraordinary conclusion he will also replace him as Julianne’s groom, the wedding of Michael and Kimmy becoming also that of George and Julianne, giving the film’s title a final twist.

The nature of the relationship between Julianne and George is gradually defined through their scenes together: a mutual dependency that is neither romantic nor sexual, hence free of the demands, restrictions, and jealousies of “traditional” love relationships. If an overtone of male dominance remains, it is one that Julianne can reject whenever she wishes: professionally he is her editor (though neither the film nor the character makes anything of that), personally her wise adviser—not so much because, as a man, he knows better, but because, as a gay man, he can view from the outside the social conventions and behavior patterns from which Julianne has never quite emancipated herself. His concern for her (because he senses that she is going to behave badly, in ways of which she will be ashamed) never expresses itself as even remotely bullying or dictatorial, and it is always balanced by his fear of losing her: Michael’s instant jealousy when he believes Julianne and George are lovers is balanced by George’s sense of loss when he believes she will be absorbed in a traditional marriage. If he is her “best friend,” it is clear that she is also his; if this is not what one normally thinks of as a “love” relationship, perhaps our definition of love needs rethinking.

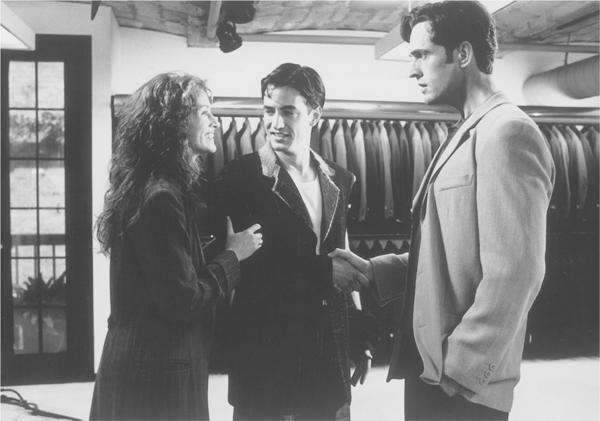

My Best Friend’s Wedding

The innocent bride (Cameron Diaz, right) and her maid of (dis)honor (Julia Roberts)

A startled George (Rupert Everett, right, with Julia Roberts and Dermot Mulroney) learns that he is suddenly Julianne’s fiancé

The film takes over from Muriel’s Wedding the use of a song associated with the heroine and becoming a marker of her development, but it develops this device far more elaborately and satisfyingly. There are, in fact, two songs involved, one associated with Julianne’s relationship with Michael, the other connected to her relationship with George. “Just the Way You Look Tonight” is introduced in the sequence of Julianne’s first serious (and almost successful) attempt to break up Michael’s relationship with Kimmy—the restaurant scene where Kimmy, at Julianne’s instigation, asks Michael to work for her father in an office job for six months, enabling her to fulfill certain life choices (finishing college, beginning her own career in architecture) instead of sacrificing everything for him: he arrives for lunch singing it to Julianne, as a memory of their romantic fling. He sings it to her again on the sight-seeing launch and they dance together, publicly, yet seemingly completely unaware of the presence of outsiders. He has by this time admitted that he felt “crazy jealous” of George, and his revived attraction to Julianne has become very evident; it’s the moment that convinces her of her right to break up the marriage, which can’t possibly be a happy one, the couple being hopelessly incompatible and Michael still being romantically attached to her, releasing her from her last promptings of conscience or consideration for others, enabling her meanest and most reprehensible action. George’s song, introduced at the eve-of-wedding luncheon, is Burt Bacharach’s “I Say a Little Prayer for You” (“Forever, and ever, you stay in my heart/ … Forever, and ever, we never will part”). George introduces it in relation to his account (hilarious, and totally fictitious) of his first meeting with Julianne, and it is immediately taken up, first by the two bridesmaids, then by the entire assembly: it’s important that it becomes a public song, symbolically uniting the supposed couple with an outside world, while the Michael/Julianne song is strictly personal and hermetic, shutting the world out.

In the final scenes the two songs are juxtaposed, representing the choice that Julianne must make. In her obligatory “maid of honor” speech at the wedding reception, Julianne publicly acknowledges the ugly and psychopathic nature of her behavior, then confers the song she shared with Michael upon the new couple, as her wedding gift, “until you find your own song.” It is her way of relinquishing her obsession, and with it the past. After the couple leaves for the honeymoon, the reception continues. Julianne is alone among the crowd. Her cell-phone rings: George of course. But George is there, at another table, and he presents her with what is effectively his wedding gift to her: “I say a little prayer … ” We are then given an entirely new variation on an old convention (a convention that will be repeated, shopworn and totally unconvincing, in its original form, at the end of Roberts’s subsequent Notting Hill): the public proposal. George advances toward her across the floor, making it clear that what he is offering is a permanent relationship: “And though you quite correctly sense that he is—gay, like most devastatingly handsome single men of his age … There won’t be marriage. There won’t be sex. But, by God, there’ll be dancing.” Earlier in the film Michael had protested to her at the ballpark (her dancing with the best man at the reception being in question) that “You can’t dance. When did you learn how to dance?” Their dance together on the launch was slow, tentative, private; her dance with George is abandoned and ecstatic, a dance of liberation. The film closes on “Together, forever … ” The film thus fulfills the traditional Hollywood obligation to progress toward the “construction of the couple,” but it is no longer the “construction of the heterosexual couple.”

As with The Daytrippers, it is a simple matter to relate My Best Friend’s Wedding to classic screwball: indeed, it directly evokes Bringing Up Baby, which was also about a woman determined at all costs to prevent a man from marrying his fiancée within a short period of time. In the 30s, Katharine Hepburn would have played the Julia Roberts role and the ending would have been a foregone conclusion: the prospective bride would have been revealed as either an idiot bimbo or a calculating bitch, hence jettisoned without the least discomfort for either the other characters or for the audience—the groom would have realized his terrible mistake, Hepburn would have replaced the bride at the altar in a breathless last-minute upheaval, and the wedding would have formed a triumphant conclusion. That is precisely how I “knew” the film would end the first time I saw it, though I was increasingly disturbed by the question of how it would manage to jettison Cameron Diaz without doing itself irreparable damage: her character was simply too sweet, too lovable, too vulnerable, too sincerely in love. Another source of disturbance was that the Cary Grant role seemed somehow to have become split between Dermot Mulroney and Rupert Everett.

GAYS IN 90S COMEDY: PROBLEM OR SOLUTION?

What above all distinguishes My Best Friend’s Wedding from classic screwball is something that couldn’t have happened in any mainstream film prior to the 60s, and didn’t in fact happen before the 80s: the inclusion of a character who is not only openly gay but is represented positively and attractively. Rupert Everett’s George is very different from the grotesques and lost souls who first represented gays when the taboo on explicit gay representation was lifted in the 60s (Boys in the Band, Staircase, The Killing of Sister George … ): in every aspect but the sexual he is an ideal partner for Jules. Recent films are beginning to suggest that the right-wing dread of the “gay lifestyle” is not without foundation: what is feared is not merely that, were gayness viewed positively, virtually everyone would immediately become homosexual, but rather that gay relationships might become a model for a new, freer, alternative “normality.” It is not, when you think about it, in the least surprising that the collapse of confidence in the traditional norms would be accompanied by the sudden emergence of images of attractive gay men leading apparently happy and productive lives. The apparently open arms with which gays have suddenly been welcomed in recent Hollywood cinema have not yet opened indiscriminately: gays have been mainly restricted to comedy, where there is less need to show sexual acts or even expressions of love. The gay love story is a genre so far restricted to small films aimed at gay audiences (Making Love was generally ridiculed by gays on its appearance, but its audacity seems now proven by the fact that it has still, twenty years later, had no sequel). Hollywood remains rather wary of gay couples, though they are beginning to appear in some surprising places (Big Daddy, Go). The most radical use of gay characters is once again in The Daytrippers, where the final breakdown of the marriage and the dissolution of the family coincides with—is indeed precipitated by—the discovery not only that the husband has indeed been unfaithful, but with another man: on the symbolic level, the co-incidence of the collapse of norms with the production of a gay relationship is eloquent.

A favorite (and logical) role for gays in the new Hollywood comedy was quickly discovered: make the gay character the heroine’s best friend (The Object of My Affection, Blast from the Past) and the problems are solved, the potential embarrassment of the more repressed and inhibited members of the audience averted. My Best Friend’s Wedding seizes on this and brilliantly turns its limitations to advantage: the film’s use of the Everett character is exemplary in its intelligence. George’s maturity, considerateness, tact are intimately connected to the gayness that sets him apart from the social norms, permitting him a wise distance from the practices and conventions in which those around him are entangled. He is able to talk to Jules in a way that would be impossible for a heterosexual man, offering her always an intimacy that is the closer for being nonsexual. Hence the film’s remarkable culmination, its “happy end” which becomes the securer alternative to the marital union which Jules has renounced, in its way an alternative “marriage”: George’s public speech to her, at the wedding reception for her “best friend” and the woman of his choice, constitutes a veritable proposal, the commitment to a relationship that will be permanent but nonexclusive, built upon much sounder foundations than romantic love or sexual attraction. As a friend of mine once wisely said to me, “You should live with friends, not with lovers.” The film leaves us with the question of which man is now her best friend, and whose wedding is this anyway?

The implications of all this are far-reaching. I omitted—in my rough list of what, in gay life, the Hollywood cinema continues to suppress or skirt rather uneasily around—the question of sexual freedom. This is why My Best Friend’s Wedding can tell us little or nothing about George’s sex life. There is one brief scene which may offer a clue, the scene where Julianne, desperate, calls up in the middle of George’s dinner party to beg him to come to her aid. George is at the head of the table, as host; to his left and right are two presumably straight couples; at the other end (where traditionally the wife would sit) is a bald-headed man, briefly glimpsed: are we to take him as George’s lover? As another friend? There is no clue other than his position at the formal table. The right talks of “the gay lifestyle,” but in fact gay life comprehends many distinct lifestyles. There is reason to believe that the original model for gay couples, imitated from the only obvious available model and imitating traditional marriage—ostensible monogamy, with “cheating” (horrible word, horrible concept!) on the side, with the resulting rows, growing tension, and constant suspicions—is gradually dying out. More gay couples are accepting the natural polygamy of (most?) human beings and ceasing to regard sexual behavior outside the relationship as “infidelity” (another horrible word, as commonly used) since the couple remains, essentially, faithful to each other. But to “live with friends, not with lovers” would remove any lingering residues of the past, the jealousies, tensions, and quarrels. The very notion of “the couple” need no longer have the status it still retains: why not three, or four, or more, and what would it matter if the relationships were sexual or not? It would not of course be necessary to share the same living space (there is no suggestion in the film that Julianne and George will live together).

And what would be the consequences if such practices spread to the heterosexual world?

Surely, for many, the release from all the strains of traditional marriage-and-family would entail, above all, a vast sigh of relief. Freedom of choice: you could, if that was what you wanted, have sex with only one person for the rest of your life (so long as you didn’t insist that he/she do the same) or with a hundred thousand. You would still, if you wished, and if you found the right person(s), have permanent or semipermanent relationships, and they would be built upon the very strong bonds of common interests and compatibility, not on the quicksands of sexual desire and “romantic love,” both of which seem to fade rather quickly. How many couples, gay or straight, do you know who still have passionate sex (rather than sex-as-duty or sex-as-routine) after ten years of living together?

All that remains is the question of children: how they would be conceived and born? how they would be raised? And, really, all that needs to be discarded is our culture’s obsession with biological parentage, which is merely a form of possessiveness and pride (one of the seven deadly sins!). Our entire culture conspires to suggest to children, almost from birth, that it is a matter of enormous and far-reaching importance who are their fathers and mothers. Yet, within our civilization, by far the largest portion of neurosis (with its concomitants of inhibition, repression, anxiety, generally stunted potential, and in the more extreme cases far more disastrous results) develops within the traditional family, passed on from generation to generation. Speaking personally, I certainly include myself in this, but I also include virtually everyone else with whom I have come into close contact throughout my life. The damage is irreparable: Why do we want it to continue? There would be no problem in producing and raising children within the various possible versions of social organization I have outlined: surely, today, we can dispense with antiquated notions about “bastards” and “children born out of wedlock”? A child should be free to relate, on a primary basis, to people other than her/his biological parents; should, in fact, have a similar freedom of choice to that of adults. And sex would fulfill its evolutionary trajectory, its growth through the millennia from mere reproductive agency to its ultimate destiny: the sharing of pleasure, affection, and intimacy among human beings.

1. “Cary Grant : Comedy and Male Desire” (CineAction 7).