IS AN OPPOSITIONAL CINEMA POSSIBLE?

The immediate—and obvious—question: Was it ever? I suggested in the new prologue to this edition that certain films made during the classical period can be read as, at least potentially, “radical” or “subversive,” but were they at the time? The answer is, almost certainly not—neither by audiences nor by reviewers, and in most cases probably not even by their directors. The explanation lies above all in genre and its conventions. I take as exemplary three films that I regard as masterpieces (I in fact included them in my latest list for the international critics’ poll Sight and Sound organizes and publishes every decade in choosing the “10 Best Films of All Time”): Rio Bravo, Rally ’Round the Flag, Boys!, and The Reckless Moment.

In its day, and perhaps even now, many critics have regarded Rio Bravo as a right-wing response to the “liberal” High Noon; today it is easier to read it as an early assault (translated into the mythic terms of the classical western) on corporate capitalism (represented by the Burdetts) by a group of heroes whose values have nothing to do with money or greed—thereby highlighting not only capitalism’s manifest inequities and iniquities but also its dehumanizing effect on its practitioners. It is likely that general audiences of the time (1959) saw it as neither: it was “just a western.” Rally ’Round the Flag, Boys! was even easier to cope with and render safe: it was a (very late) screwball comedy, hence, by definition, not to be taken seriously. What was the social/political force of these films when they appeared? Probably zero. One cannot, of course, estimate their unconscious effect, but there is no indication whatever that they led to any social change. It is also not just possible but probable that their makers were completely unaware of their potentially explosive content. If McCarey, especially, had understood the content of his own best films he would probably have felt compelled to denounce himself, along with certain of his colleagues, to the McCarthy era’s Un-American Activities tribunal (see the essay on McCarey’s work in Sexual Politics and Narrative Film).

The Reckless Moment is a somewhat different case: it is built upon the interaction between two genres whose potentially radical content was always closer to the surface (the woman’s melodrama, film noir), and it was directed by an outsider, a European émigré marginally associated with Bertolt Brecht, who was a far more conscious artist (more conscious than Hawks or McCarey of being an artist), not just a “popular entertainer.” The film—having throughout its length provided a meticulously detailed analysis of the repressions, the subjugated tensions, the resentments and frustrations on which the patriarchal nuclear family is constructed—seems to offer in its final scene a characteristic generic escape route: the disruptions are removed, order is restored, the family members gather in the entrance hall of their domestic prison for the absent father’s phone call from Berlin—the classic “happy end.” But one can take it so only if one is totally impervious to the art of mise-en-scène. Ophuls shows us that the patriarchal family is not merely restored but reproduced, the whole sorry mess repeating itself: the rebellious daughter in her mother’s fur coat, the rebellious son in a neat, respectable suit, the black maid relegated once again, after her shortlived prominence, to the background of the image, the camera finally descending to show the mother, as she mouths her Christmas platitudes, behind the prison bars of the banisters. One will find no equivalent in The Deep End, the recent remake.

But if these films had no discernible social effect when they appeared, what, then, was/is their use? My answer is that they are of inestimable value to us today, not just for the manifold pleasures of their realization by directors of genius, but for their insights into the profound unease and dissatisfaction with the structures of Western capitalist civilization which they so clearly dramatize, our culture’s Collective Unconscious. All those tensions that finally erupted in the great radical movements of the 60s/70s are already demonstrably there. They just hadn’t been recognized for what they were.

Crucial to these works (including, to a great extent, The Reckless Moment) was the relative lack of self-consciousness. Hawks, for example, could become, intermittently, a great artist: the circumstances of Classical Hollywood permitted it, even encouraged it, without the least awareness of doing so. Only Angels Have Wings and Rio Bravo can be read as offering a complete and satisfying (if primitive) philosophy of human existence, developed spontaneously and organically out of a whole complex of interlocking factors (genre, writers, actors, cinematographers), while Hawks himself appeared to believe that he was just “having fun.” That kind of unself-consciousness, a prerequisite of full, free-flowing creativity, is no longer possible. Today, a filmmaker of ambition cannot be simply the central controlling and organizing factor within a spontaneously evolving work: he is “making a statement.” Consequently, although surrounded by actors and technicians, he works in terrible isolation: the statement must be his, it must be consciously intended, it cannot simply evolve. There is a sense in which even art as closely and densely “worked” as the greatest plays of Shakespeare developed out of communal experience (genre, conventions, preexisting forms and materials, a sense of cultural belonging). The possibility still existed, to an extent, in the 1980s and early 90s—witness the greatest achievements of that period, Raging Bull, Heaven’s Gate, the “living dead” trilogy. All are marked to an extent by a degree of self-consciousness quite alien to Hawks or McCarey, but all retain a sense of free-flowing creativity, a spontaneity, a readiness to take chances, to try anything and see if it works.

Fifty years from now, circa 2053, will critics be discerning comparable radical impulses in today’s Hollywood movies? It’s possible, I suppose, but it seems unlikely. For a start, we have become far more self-conscious, hence more wary, more on our guard. Films may have become more “daring” in terms of sexual explicitness and extreme violence, but such things have nothing to do with social/political subversion and our internal censors will warn us against anything more dangerous than the spectacle of crashing cars and exploding buildings, created with the aid of the latest technology. The grotesquely reactionary period we live in is not far enough removed from the upheavals of radical feminism, black power, gay rights, to have lost awareness of them; their partial cooption into the mainstream does not entirely remove their potential threat. Filmmakers are now largely under the control of vast capitalist enterprises whose aim seems to be distraction, not disturbance. And, with the now increasingly patent devastation of the planet, environmentalism is likely to grow in force and supporters. But the majority, as yet, remain in the state of stupefied mystification that corporate capitalism requires for its continuance: Shock us, make us laugh, but please, please, don’t encourage us to think.

The past few years have not been entirely devoid of movies critical of American institutions. Two recent ones come to mind, Spy Game (the CIA) and Training Day (the police), both raising questions of corruption and morality, professional duty/personal loyalty. They have certain features in common: each juxtaposes an experienced older man (Robert Redford, Denzel Washington) with a young novice (Brad Pitt, Ethan Hawke), with the advantage of a duo of intelligent and gifted male stars, giving each film a certain distinction. Both are flawed (Spy Game far more seriously) by two of the prevalent diseases of contemporary Hollywood filmmaking, respectively overediting and the apparent inability of the current action thriller simply to end. The point of hysterical overediting appears to be that it offers speed, thrills, excitement; it chief effect is to permit the spectator no opportunity for thought. The very real moral questions that Spy Game raises concerning CIA ethics are drowned in a welter of images that dazzle the eye and numb the intellect, and a film that should have encouraged serious reflection ends by annihilating it. It needed a Preminger; it got Tony Scott.

Training Day is altogether more impressive—an audacious, outspoken, and disturbing examination of pervasive corruption within the American police system. At the height of film noir in the 40s it would have come as no great surprise, but in the contemporary context it stands out like an exemplary sore thumb … until its last ten minutes. Is there really a demand today, at the “final” climax of an action or horror movie, for a whole series of endings in which either the hero or the monster survives what appears to be certain death, to come up for yet another bout of violence? It wasn’t necessary to the original Frankenstein, for example, or its first two sequels, but in Hollow Man Kevin Bacon has to be rekilled ad nauseam, post-absurdity and beyond tedium, and in Training Day Ethan Hawke has to survive a comparable series of apparently lethal disasters before, inevitably, “good” can triumph over “evil” (yes, there are problems with the police but one good man can overcome them … ).

I end by offering brief accounts of two contemporary filmmakers of variable distinction who might be considered “oppositional,” one who has attempted to operate within the mainstream, one who has located himself firmly outside it.

THE STRANGE CASE OF DAVID FINCHER

Within the contemporary Hollywood mainstream, David Fincher’s films stand out as, to say the least, an anomaly. Their most immediately obvious quality is their darkness and drabness: colors tend to be muted, reduced to a narrow range of grays and browns; their tone ranges from the overwhelming pessimism and despair of Seven (1995) to the caustic, brutal near-nihilism of Fight Club (1999). Whatever one feels about the films’ success or lack thereof, they cannot be accused of providing the mere mindless distractions that characterize most of the current Hollywood fare. Even the more conventional Panic Room (what Hitchcock used to call a “run for cover” movie, a built-in commercial success after Fight Club’s spectacular audacities) is recognizable as a Fincher movie from its drab lighting and narrow tonal range.

Seven, the most completely achieved of Fincher’s films to date, stands somewhat apart from my current concerns, its engagement with the contemporary social/political realities swallowed up in what comes across as a form of existential despair about “the human condition.” Richard Dyer, in his meticulously detailed, brilliant, and perhaps definitive BFI Modern Classics monograph, sums it up: “The film is a single-minded elaboration on a feeling that the world is beyond both redemption and remedy.” On the other hand, Alien 3, The Game, and Fight Club form a kind of loose, uneasy, and unstable trilogy about the ravages of corporate capitalism.

Alien 3 (1992), besides being the darkest, most disturbing, and most coherent of the four Alien movies so far, is easily the most successful and least compromised of this trilogy, and this is surely because it’s primarily and unapologetically a genre movie, “just entertainment” about good guys and bad guys, and can therefore get away with anything; the cost of this is that it is forced to waste much of its time (throughout the middle section) providing (very efficiently) the kind of shocks, suspense, and thrills that audiences for the Alien films expect. (Significantly, it appears to be the least popular of the four.) Only in its final third does it really play its hand, cards down.

The film’s ultimate villain is not the alien but “the Company” (corporate capitalism in miniature). Its audacity can be gauged from its choice of opposition: not just Sigourney Weaver (intelligent and formidable as she is), but the earth’s worst criminals, the multi-rapists and serial killers who populate the tiny planet that has been converted into a maximum security prison to which they can be deported, the strategy being to suggest that the evil represented by the Company is far worse, since it places the entire human race in jeopardy. The film’s ending approaches sublimity. The confrontation between Ripley (the new alien in her womb) and the head of the Company (Lance Henriksen) on the platform above the vast vat of molten ore opposes human emotion, human conscience, to the naked greed for power: with the alien as its weapon, the Company can achieve world domination or the annihilation of human life on the planet. Ripley’s self-sacrifice transforms her into a veritable Christ figure, giving her life to save humanity.

From the sublime to the ridiculous. The Game (1997) is a genre movie manqué, a disaster that might have been a near-masterpiece. If you forget its last ten minutes ever happened, you have a fascinating update of film noir. All the major ingredients are there: the nocturnal city, with menace lurking around every corner, an atmosphere of all-pervasive deception and treachery; the protagonist/victim struggling, first, to make sense of what is happening to him and, subsequently, just to survive; the ambiguous woman, who may be his loyal supporter but may equally be the archetypal femme fatale; the villains (who could be anyone or everyone) motivated solely by the greed for possession; no one to be trusted, not even the protagonist’s younger brother. The absolutely logical and topical updating lies in making the ultimate villain “big business” itself, the protagonist the millionaire head of a corporation in a dog-eat-dog world, the macabre twist that he is lured to his destruction by being led to believe he is participating in an elaborate game, gradually revealed as deadly, the stakes his wealth, his position, his identity, and ultimately his life.

The film should have been a magnificent “fable for our time.” Our credulity may be strained at times (could even the wealthiest, most powerful amalgamation of businessmen organize a “game” on this scale, utilizing the resources of an entire city?), but here generic convention saves the day: film noir has accustomed us to the extremes of paranoid reality/fantasy, and the extra step we are invited to take is easily accomplished by a “willing suspension of disbelief.”

Yet all this promise goes for nothing. I know of no other film that is so completely destroyed by a trick “happy ending.” Even the notorious “It was only a dream” ending of Lang’s Woman in the Window can be justified by a close look at its opening scenes, and the film’s essential meaning remains undamaged. But the revelation of Fincher’s film (it really was only a game) does irreparable harm on all levels. It isn’t merely a matter of plausibility (though credulity is no longer strained, it is totally shattered, the entire film becoming patently ridiculous). The far more serious damage lies in its self-betrayal. Far from defining the world of corporate capitalism as a monstrous extension of the noir vision, it now tells us that everyone was basically benevolent, that the “game” (in which Michael Douglas might have been killed half a dozen times) was just a kind of jolly romp to turn him into a better human being. He used to be a nasty capitalist tycoon, now he’s going to be a nice one. Yes, it’s as banal as that …

I don’t find Fight Club a success on any level, but one can say, positively, that it at least represents some kind of disturbance within the all-pervasive distractions of contemporary Hollywood—an intervention both incoherent and irresponsible, but an intervention nonetheless. Its chief interest is that it ever got made at all. It could not, as it stands, have been made after September 11, 2001, because it can be read (with some difficulty) as condoning terrorism. It can also be read, with only a little less difficulty, as denouncing it. In the last resort it appears to be unreadable, like its obvious forerunner, Bergman’s Persona.

Persona, equally the forerunner of David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. (2001), has proven a disastrous model, largely because what is imitated is (infallibly it seems) its worst part. The abrupt rejection, around two-thirds to three quarters through each of the three films, of a more-or-less coherent narrative with carefully defined characters, the collapse into “anything goes” pseudo-avant-gardism, is in each case taken by the filmmaker as an invitation (from himself, to himself) for indulging his own personal obsessions. This is nowhere more obvious than with Bergman himself (as I discuss at length in the essay on Persona in Sexual Politics and Narrative Film), but both Fincher and Lynch use it as a self-authorized license to irresponsibility: the move to some (undefinable) “other level of reality” gives them the freedom to get away with anything.

Fight Club differs from Persona in that its narrative (we suddenly discover) was unstable from the outset: whereas in Persona (and in Mulholland Dr.) the two women are (fictionally) “real” until the breakdown moment (which in Lynch’s film may imply that everything we thought was real was a dream), Tyler Durden/Brad Pitt has never existed except as the (nameless) narrator’s (Edward Norton) alter ego or “demon” self, the self he would unconsciously like to be but isn’t. Otherwise the parallel holds: there is even the equivalent (in both films a kind of tremor before the earthquake) of Persona’s projector-breakdown: the sudden instability of the camera when Norton begins to doubt Pitt. In Fight Club the “earthquake”—the moment when the reality level definitively changes—is the car crash, in which we may well believe that “both” men were killed, it being difficult to imagine anyone surviving more or less unscathed. Before it, the narrative (given the expectations of extremely stretched plausibility to which the contemporary action cinema has accustomed us) can just about be accepted as plausible; after it, it cannot. The car crash is closely followed by the scene where Norton (who may or may not be dead) wanders downstairs in the building he has been occupying to find that the previously modest “fight club” has suddenly transformed itself into a vast terrorist organization, manufacturing weapons of destruction in his own cellar. This in its turn is followed by the scene in which Tyler Durden reveals that he has no independent existence but is simply Norton’s hidden self, summoned up to do all the things Norton would never dare.

Fight Club: The original poster

Norton (a sort of modern “Everyman” character, a reading underlined by his namelessness) has (we deduce) summoned up Tyler out of his disgust and disillusionment with contemporary civilization and his own position within the business world, the world that Tyler exists to (literally) blow up. It’s a wonderful and audacious concept: one may speculate that Fincher wanted to make the film as a correction to The Game. But the film’s potentially explosive force is largely dissipated in its confusions. There seem to be two (quite incompatible) ways of reading the ending, partly depending on whether you see the narrator or Tyler Durden as the film’s “hero”:

1. Terrorism is not pretty, but it’s the only way to overthrow corporate capitalism, therefore it must be accepted—hence the narrator has been merely cowardly in rejecting his “other” self and trying to prevent the cataclysm. The support for this is partly the satisfaction the film offers its audience in watching the final collapse of the buildings as the explosives go off, Tyler having made it clear that the primary targets are the headquarters of the major credit card companies: all credit card debts will be wiped out, a fantasy that must surely appeal to the vast majority of the film’s spectators. But this reading is further supported by the fact that, during the final stretches, everyone in a subordinate position (including restaurant workers and even the police) appears to have become a member of the underground organization: it is a popular movement, a people’s revolution.

2. Corporate capitalism is a great evil but terrorism (the only challenge to it the film offers or even hints at) is brutish, wasteful, ugly, and purely negative: the narrator was right to denounce his alter ego. (We may note that Tyler himself has named the revolution “Project Mayhem,” although he also claims, impossibly, that no actual people will be harmed in the explosions.) This reading is supported by Fincher himself in his audio commentary on the DVD, where he compares Tyler’s assembly of fight club initiates to the Nuremberg Rally; and in the actors’ audio commentary there is a concerted effort by everyone to suggest that the members of Fight Club are fascists and morons. As membership, by the film’s climax, seems to include most of the working class, this verdict may strike us as somewhat sweeping.

Fight Club: Infectious waste

I find both these available readings politically irresponsible, and the unresolvable clash between them, together with the film’s failure to suggest that there might be a positive alternative in the form of organized political protest, simply repeats the despairing cynicism of The Game in a different form. Ultimately, the film panders to that section of the public (unfortunately a large one) that requires a further dose of impotent desperation to prevent it from starting a real political revolution. Fight Club raises the question of whether it is possible to make a radical movie in Hollywood today, and answers it, by implication, in the negative.

JIM JARMUSCH: POET OF ALIENATION

“America is a big melting-pot … When you bring it to the boil, all the scum rises to the top.” —John Lurie in Down by Law (1986)

Excluding his first, which I have never had a chance to see, Jim Jarmusch has written and directed six fictional films, which fall neatly and chronologically into three pairs:

1. Two films in black-and-white (the only ones prior to Dead Man), studies in urban alienation and attempted escape, built upon the uneasy friendship between two men and an outsider (in Stranger Than Paradise a young woman, in Down by Law Roberto Benigni).

2. Two multiple-narrative films, taking place during a single day or night: three overlapping stories (Mystery Train) set mainly in the same rundown hotel; five stories taking place in different parts of the world (Night on Earth).

3. Two films within what would normally be regarded (if this wasn’t Jarmusch) as an “action” genre: a western (Dead Man) and a samurai movie (Ghost Dog), in both of which the “hero,” signified as doomed from the outset, is shot down at the end.

I have always enjoyed Jarmusch’s films, in a casual sort of way, but it had never occurred to me to write about him until I saw Dead Man (1995), and there I doubted my ability: I didn’t feel sufficient contact, our sensibilities seemed too remote. I still have difficulty entering the Jarmusch world (seductive as it is to an outsider), and what follows is necessarily tentative. But in the context I have set up, some attempt seems unavoidable: he is one of the only contemporary American filmmakers of consistent and distinguished achievement who has dared to say a resounding No! to contemporary America. I am careful to say “American” filmmaker, not “Hollywood,” his one apparent flirtation with mainstream cinema, Night on Earth (1991), culminating—if I have understood correctly—in his emphatic rejection of it. Instead, he has reached out repeatedly to compatibly idiosyncratic European “arthouse” filmmakers, aligning himself with their work (Claire Denis in France, the Kaurismakis in Finland, both acknowledged in Night on Earth in the Paris and Helsinki episodes by his use of actors associated with them), as well as to less-than-“respectable” American individualists (he made a documentary about Samuel Fuller). Reseeing the films today, in their chronological sequence, has greatly increased my affection for them and (with certain reservations) my commitment to them. It is probably impossible today for anyone to make an even halfway commercial movie that shouts, in some positive sense, “Revolution!” as loudly as its lungs can bear, so one must celebrate the films that seem (whether deliberately or not) to imply its necessity.

Jarmusch’s male characters are both like and unlike the wanderer of the traditional western: like, because they too are inveterate wanderers; unlike, because the westerner either is escaping from something in his past or is a man with a mission, frequently revenge, sometimes, like Shane, in the service of the good but vulnerable. Jarmusch’s wanderers are essentially motiveless: they wander simply because they are totally alienated from the culture through which they move, which is invariably even stranger than they are themselves. There is only one character in all the films whom we see in a fixed residence, and the “home” is a rooftop populated mainly by carrier pigeons, the domicile a rough shack erected beside the cages: the black samurai (Forest Whitaker) of Ghost Dog. Even he, in his chosen profession, is traditionally a wanderer, and without personal motivation, paid for hire by a “master” whose “retainer” he has elected to become, killing people because he is instructed to. Otherwise, Jarmusch’s characters (the men, and most of the women) are seen in cheap, temporary, barely furnished apartments (the first two films); in prison (the middle section of Down by Law); in decrepit hotels (Mystery Train); in taxis, as drivers or passengers (Night on Earth); or astray in the western wilderness (Dead Man). Typically, they inhabit a barren world, a world without a past, without traditions, without a cultural history; they come from nowhere and have nowhere to go.

In the two early films these alienated wanderers are all we are allowed of identification figures, and identification is extremely problematic (though one suspects that Jarmusch identifies with them to an extent, whilst presenting them ironically). They never seem aware or intelligent enough to fight or protest; their alienation is passively accepted, as a fact of modern existence. Women, on the other hand (though, after Stranger Than Paradise, they seldom figure very prominently, the two multinarrative films providing the chief exceptions), are the settlers, though as unlike the heroines of John Ford as it is possible to get: they appear to have accepted the civilization as it is and are making the most of it, which makes them quite impossible identification figures in the Jarmusch world. The exception here is Eva (Eszter Balint) of Stranger Than Paradise, the only woman in a Jarmusch film who seems privileged and valued above the men (who treat her abominably); there is no comparable figure in the later films, though Winona Ryder and, especially, Beatrice Dalle in Night on Earth both come close. Eva stands up to men without making demands on them (which these men could never meet), and becomes the film’s emotional center as well as its center of intelligence. Insofar as we are allowed to identify with anyone in the film, it is with her. But, especially in the early works, Jarmusch’s stylistic decisions preclude identification rigorously: no point-of-view shots, no use of that old Hollywood standby the shot/reverse-shot pattern. This stylistic rigor is relaxed slightly in the multinarrative films but returns in full force in Dead Man. One guesses that Godard was an influence on the first two films, which are replete with the alienation devices that Godard learned from Bertolt Brecht.

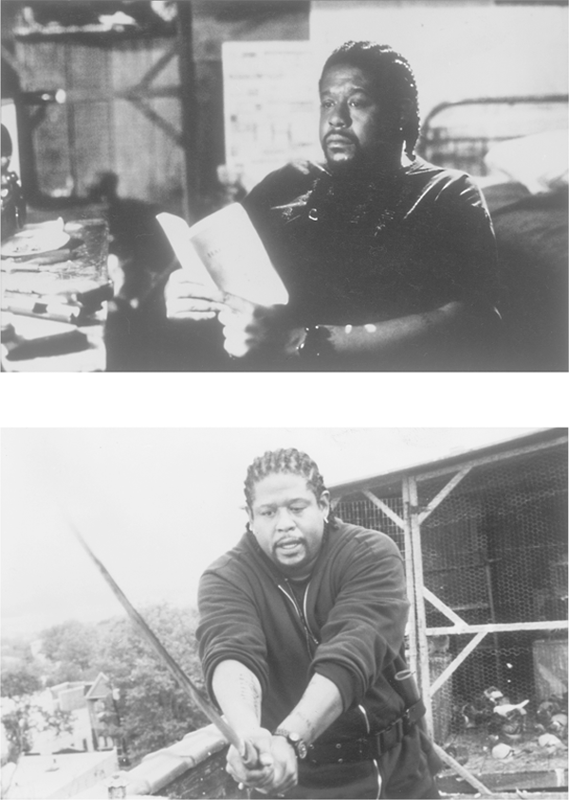

Ghost Dog: “Ghost Dog” studies and practices “The Way of the Samurai”

The ironic stance of the first two films is … not lost … but partially and intermittently submerged until you get to Dead Man. Night on Earth can be read as a turning (back) point, even a moment of hesitation. Each episode is built upon a confrontation between the cab driver and his/her passenger(s). The first four are all essentially duologues; the first three are constructed upon two people learning to understand and respect each other, despite differences of class, nationality, and color/handicap (respectively). We may not, first time around, notice (I didn’t) that the episodes, as they move east, become progressively pessimistic about human contact. The first (Los Angeles: Winona Ryder/Gena Rowlands) is surely the nearest Jarmusch has come to “feel good,” both women strengthened by their mutual understanding; the second (New York: Armin Muller-Stahl/Giancarlo Esposito) ends with the two men liking each other but with no real understanding; the third (Paris: Isaach De Bankolé/Béatrice Dalle)1 culminates in a kind of deadlock between them, their sense of (and affection for) each other becoming clear only after they have separated. The fourth episode (Rome: Roberto Benigni/Paolo Bonacelli) is misleading because it is so hilarious, yet here there is no mutual understanding at all: one character dies of a heart attack brought on by the other’s monologue, and we are left with a dead body propped up on a bench in the darkness. This paves the way for the final sequence (Helsinki), where contact is minimal, the ending totally desolate. It was as if Jarmusch was tempted by the lure of the mainstream but made the film as a vehicle for the expression of his rejection of it.

Dead Men

Jarmusch’s two most recent films at time of writing are both centered on protagonists who are announced as “dead” from the outset: a few minutes into Dead Man, the train fireman tells William Blake (Johnny Depp), whom he has never met before, that he has seen him drifting in a boat on the river, which is where Blake will die at the film’s end (“You think to yourself; Why is it that the landscape is moving but the boat is still?”); Ghost Dog (1999) begins with a quotation from The Book of the Samurai: “Every day without fail one should consider oneself as dead.” The two characters are linked because, unlike their predecessors, they have rejected the purely passive role of the alienated wanderer, Depp by accepting a job (which turns out not to exist) in the far West, Whitaker, more positively, by forging an artificial identity for himself as a modern samurai. Their decisions make of them totally isolated figures (Depp inadvertently, Whitaker from deliberate choice), doomed to destruction. In certain respects Jarmusch’s early films suggest lingering fragments of the hippie movement so intelligently analyzed by Arthur Penn in Alice’s Restaurant, admirable but ineffectual, the movement’s force undermined by its isolation, worn away by pressures both internal and external, so that there is no longer the least sense of community or belonging that gave it what precarious strengths it had. The stance continues into Dead Man, but suddenly becomes far more potent, the disdain for mainstream culture transformed into a bleak, icily controlled rage. It is among the most impressive American films of the past ten years, a work of startling originality and integrity. Insofar as it evokes any previous film it is perhaps Godard’s Les Carabiniers: there is a similar pervasive grim humor at which it is quite impossible to laugh, and (like Godard’s remarkable film) it evokes and pays homage to silent cinema in the starkness of its black-and-white photography, the stylistic journey back in time corresponding to the film’s backward itinerary into the American past.

The film also resembles Les Carabiniers in its stylistic fusion of apparent opposites, realism and extreme stylization. Today, the use of black-and-white photography is already a form of stylization (when it was the norm it was experienced as “realistic”). In Dead Man its distancing effect is intensified by the precise framing of iconic images, the deliberate, unhurried editing (the editing style already an affront to contemporary Hollywood). Yet, just as while watching Les Carabiniers we get the feeling that this is what war is really like (its tedium, its arbitrariness, its degradation, as well as its violence and horror), so here we feel (without having been there) that we are seeing the Old West as it really was, brutish, debased, squalid, degenerate before it could even begin to become civilized. One may reflect, as one emerges, that the idealism of a Ford, the stoic heroism of a Hawks, were probably there too, in occasional patches, yet those directors’ “natural” styles (the shooting/editing patterns to which Hollywood accustomed us) seem a deception beside what Jarmusch shows us with his schematism and stylization. The strategy is beautifully established in the film’s opening sequence, William Blake’s journey by train into the wilderness, constructed upon alternating series of shots: medium close-ups of Blake, becoming increasingly worried, insecure, and alienated; static shots of the succession of men who sit opposite him (from dignified, well-dressed townsman to rough trapper), the “moving” shots (but the train is moving, not the camera) of landscapes that become progressively wilder, culminating in the wigwams of an Indian tribe. The precise sequence is:

1st passenger: elderly, dignified, civilized

1st landscape: young fir trees (a plantation?)

2nd passenger: unshaven, cowboy hat, wife beside him

3rd passenger (off to one side): woman (mid-30s?), modest, smiling at Blake coyly (widow in need of a new husband?)

2nd landscape: woods, ruined covered wagon (abandoned)

3rd landscape: rocky, barren mountains

4th passenger: elderly, bearded trapper-type, wearing skins, long (but clean) hair

4th landscape: flat, barren desert, outcrops of rock

(We see the fireman, stoking the fire, as train enters tunnel.)

5th passenger(s): hunters, fur hats, rifles

5th landscape: wigwams, but half-demolished, no sign of habitation

6th passenger: unkempt, wearing skins, long, shaggy, dirty-looking hair, almost crazy expression.

(The culminating image is of a number of such men firing frantically out of the train windows to kill buffalo and add to the destruction of Indian civilization.)

The protagonists of Dead Man and Ghost Dog are doomed for quite different reasons. Ghost Dog himself has made a deliberate choice, distinguishing himself from the chaos, formlessness, and confusion of contemporary America: the perverse adoption of a set of codes that made sense within a different culture in a different age but here are arbitrary and artificial. It is, in its way, heroic even while its morality and sense are questionable (it involves killing people when ordered by a local Mafia associate); his downfall stems from his refusal to kill an “innocent,” drug-addled young woman, even though she is a witness to other killings. We never know exactly why William Blake has chosen to go West (because of an unhappy love affair?—but the curiously visionary train fireman dismisses this as inadequate motivation). Unlike Ghost Dog, he wanders innocently into trouble, completely out of his depth, learning to make choices only when they are forced on him, killing to survive (and he barely survives the squalid, primitive town before losing himself in the wilderness).

Ford, in My Darling Clementine (1946), attempted a clear distinction between the daytime Tombstone (civilization, order, people going to an unbuilt church, “sweet-smelling” hair oil and “the scent of the desert flowers,” the dance on the church floor centered upon “our new marshal and his lady fair”) and the nighttime (darkness, violence, drunkenness, the “Clanton” world). Jarmusch, in 1995, can give us only the nighttime version, even during the day. The most conspicuous sights that William Blake passes on his initial walk through the streets of Machine are half-finished coffins and buffalo skulls, human misery (a woman, who looks too old to be the baby’s mother, rocking a cradle), male faces of suspicion and hostility, a man getting his cock sucked in public by a prostitute (and instantly drawing a gun when he sees Blake watching): recognizable as the genesis and basis of the “civilization” we are shown in Stranger Than Paradise and Down by Law, as if there were direct continuity. Ford also saw early American civilization as turning a “wilderness” into a “garden.” In Dead Man, the only approach to a garden is suggested by the paper roses of the young woman Blake assists when she is thrown into the gutter by one of the town’s male citizens. “When I get the money,” she tells him, “I’d like to make them out of cloth.” When they are in bed, and he asks her why she keeps a gun under her pillow, she replies simply, “Because this is America.” Our final image of the town is of the paper roses lying in the gutter. That would appear to be about all Jarmusch—an intelligent and profoundly honest artist—can offer us in terms of “positives.”

The structure of the film allows, very clearly, for the construction of a very different “positive” in the form of Indian culture—the culture that the British, in both the United States and Canada, effectively destroyed. I know nothing about the working of Jarmusch’s mind, but I cannot help wondering whether, for perhaps one second, the possibility of presenting this passed through it. After all, a number of American filmmakers, with good intentions, varying degrees of intelligence, and (predictable) unsuccess, have attempted such a thing: Ford in Cheyenne Autumn, Fuller in Run of the Arrow, Penn in Little Big Man, Kostner in Dances with Wolves. The possibility is there, in the film, in the figure of the Indian who saves Blake’s life, but Jarmusch refuses its temptations from the outset. He has clearly understood that for an American to glorify Indian culture (as “innocent,” “natural,” “unspoiled,” etc.) is either hypocritical, sentimental, or both (and in any case quite useless today, whether to Native Americans or whites). Hence Jarmusch’s Indian is “Nobody” (the massively iconic Gary Farmer), an outcast from both the tribes (unspecified) that produced his mixed parentage. This gives him a certain advantage (when asked by the first group of three possible killers who else is “out there,” Blake can reply, quite truthfully if not exactly honestly, “Nobody,” and get all three swiftly shot to death). But this is in itself at best a mixed blessing: the first three are not the hired gunmen, are in fact quite innocent of malice, merely stupid and blundering. Nobody is, in fact, one more of Jarmusch’s alienated dropouts, a person without an identity, and even he is not permitted to survive the movie.

The other “positive” value the film seems to offer also emerges from Nobody: the Indian’s passionate commitment to the poems of William Blake (whom he assumes the film’s William Blake to be). He quotes: “Every night and every morn / Some to misery are born ./ Every morn and every night / Some are born to sweet delight. / Some are born to sweet delight, / Some are born to endless night … ”—the last line addressed very pointedly to Blake, the personification of America’s future. But, within Jarmusch’s America, past and present, none is born to sweet delight. Ultimately, in his films, endless night seems all that’s left.

The film’s latter half, as the action moves further from white civilization into the wilderness, seems, indeed, to move beyond any level of social criticism to a level of philosophy (which will mean more to those who belive in “absolutes” and “eternal truths” than it does to me). The commentary on American civilization continues, with the sequence centered on the corrupt and hypocritical trading post official (Alfred Molina), but this seems partly to give way to a sense that human life is in itself irredeemable, the sense of some fundamental sickness at the very roots of existence. I feel very tentative about this, but I feel Jarmusch here to be hovering on the brink, indecisive as to which way to step. The issue is not resolved in Ghost Dog, which (fascinating and estimable as it is) takes us no further.

1. The two stars are familiar to admirers of Claire Denis, in whose films they appear regularly: no one will forget De Bankolé, an icon of impregnable dignity, in the title role of Chocolat. Denis is credited as assistant director on Down by Law.