We stand before a hundred doors, choose one, where we’re faced with a hundred more and then we choose again.

—RICHARD RUSSO, BRIDGE OF SIGHS

I didn’t know my mother’s father had shot himself until twenty years after it happened, despite the fact that we lived under the same roof with him when he took his life. I only found out as my brother and I passed the home of an old woman who had difficulty with depression and had resisted treatment. I asked him how she was doing.

“She hung herself,” my brother said.

“Oh, no,” I responded. “I just don’t see how anyone could ever do that.”

“Well,” he said, “I guess it was sort of like Grandpa Koester.”

“What do you mean?” I half questioned, half shouted.

“You know, like when Grandpa shot himself.”

“What! Why didn’t anyone ever tell me?” I demanded.

“I guess we thought you knew,” he said.

Years later my sister told me that early one morning our mother had heard a gunshot. When my mother went to the basement, she found Grandpa. She rushed us off to school so we wouldn’t be there when the police and ambulance arrived. News travels fast in a small town, and my older sister learned what had happened from her friends when she arrived at school that morning. My younger sister didn’t hear about his suicide until several years later; one of her friends told her. I only now have a hazy memory of being told Grandpa had wanted to go to sleep and not wake up, probably enough of an explanation for a five-year-old. I remember wondering how someone could have known he was going to die, but I had no reference for understanding suicide. I remember riding in the family car following the hearse. As we drove past the school playground I stared out the window at my friends’ tiny figures, which seemed to be moving in slow motion. My mother never talked about Grandpa’s suicide, at least not to me.

Societies stigmatize both the victims of suicide and their families through isolation and shunning. Although I was too young to recall the impact on our family, the burden of the stigma certainly fell upon my mother. When I was a child, suicide victims were not allowed to be buried in Roman Catholic cemeteries because suicide was considered a mortal sin, and the Church justified its position by saying that it was an attempt to discourage suicide. In recent years the Church has taken the more lenient view that judgment of those who die by suicide should be left to God.

People become depressed when they experience significant losses or if their expectations aren’t realized. Although affected to some degree by our family environment, we each have an individual, highly heritable degree of vulnerability or resistance to depression. Research has increasingly proven that some of us are genetically more prone to depression. Some people simply find it easier than others to be happy. In a 2008 article for the BMJ, James Fowler and Nicholas Christakis found that people’s happiness depends on the happiness of others with whom they are connected. Happiness, like health, is a collective phenomenon. Happy people have more friends, happier marriages and fewer divorces, more successful careers, and longer lives. They learn more easily and recover more quickly from adversity.1

For those who are particularly susceptible to depression, antidepressant medications sometimes can raise their depressive setpoint. Happiness is not a birthright, but neither are we doomed to the level of happiness we have inherited. Changing our thinking is easier than changing the world. In my work, I often hear patients say, “I just want to be happy,” and my response is, “What are you willing to do to make that happen, and how will you measure it so you know when you have gotten there?” By taking control over our lives, increasing and nurturing our connections to others, taking care of our health, and developing lives that are meaningful, we can create an environment that helps us resist depression or recover from it more quickly when it occurs. When all of those are not enough, sometimes we must turn to antidepressant medications.

Depression is a common experience for gay men and women as they confront their same-sex attractions. Young LGBTQ men and women experience bullying, physical and verbal abuse, losses of support from family and friends, and disappointed expectations of their anticipated adulthood. For a mature gay man who has passed as heterosexual for many years, the effects may seem subtler, the most common theme being isolation and loneliness. Once I was at a holiday cocktail party and someone turned the television to a college basketball game. Most of the men immediately gravitated to the television set, but two of us who had little interest in the game—but little else in common—remained staring at each other over the punch bowl.

In that moment, as a mature gay man with same-sex attraction, despite being socially active and well liked in my heterosexual community, I barricaded myself emotionally. Many gay men experience similar instances, fearful that too much intimacy might expose their so-called abhorrent desires. In the novel Blue Boy, Rakesh Satyal writes, “Nothing is more terrifying than knowing that one glance out of place could destroy my whole existence.”2 For a closeted gay man whose life has been primarily interwoven in a heterosexual world, thinking of leaving the security of that known world can be paralyzing. Isolation and loneliness appear preferable to the unknown but anticipated rejection from the community.

Feelings of loss can accompany loss of a loved one, a pet, a body function, a job, a home, or a community. A sense of loss also occurs when what we expect doesn’t materialize. For a few months after my mother’s death, I experienced waves of grief. At first the waves would nearly drown me or smash me against the rocks of loneliness and loss. Then they would subside but be followed by another wave, another crash, and then another period of calm. Over time, the waves lost amplitude and frequency, but any unexpected reminder of my mother would trigger an occasional staggering wave of grief.

Depression spans a spectrum of disorders ranging from mild interference with daily function to a sense of hopelessness and a wish to die. Depressed people say that the pain of depression is far worse than the pain of cancer, kidney stones, and childbirth, but those who’ve never experienced depression can’t imagine what being depressed is like. Depression is different from uncomplicated bereavement. Depression can occur unrelated to loss; sometimes it doesn’t even include feelings of sadness. Emptiness or agitation is common. What psychiatrists call neurovegetative symptoms always accompany depression: difficulty sleeping, apathy, exaggerated guilt, low energy, difficulty concentrating, and changes in appetite. One man told me he couldn’t decide which way to walk around his truck. Another woman said she couldn’t decide which button on her blouse to button first. We do these things automatically without ever realizing that we’re making decisions, but for depressed people, thinking becomes like swimming in molasses, and indecision overwhelms them. When severe, these symptoms significantly compromise functioning.

All depressed people seem to think in a similar way. Predictable distortions in their thinking occur. The thinking of depressed people more closely resembles the thinking of other depressed people than it does their own thoughts from before they became depressed. The word should begins to dominate their thinking. They focus on the way they feel to the exclusion of the feelings of others. They see their situation as irreversible and all-encompassing. Depressive frameworks dominate their thinking and create overly harsh judgments about themselves.

Depressed people have a certain kind of distorted logic that makes a great deal of sense to them but to almost no one else. I often tell patients that it’s like having Vaseline on your glasses; no matter how much you strain your eyes, nothing comes into focus. Suicide begins to look like the only rational way to relieve the excruciating pain. I imagine that my grandfather’s thoughts prior to his suicide went something like this: “I am in more pain than I could have ever imagined. I can see no escape. Suicide is the only thing that will make the pain end. My death will be difficult for my family, but my life is toxic to them. My living will hurt them more than my dying.” Depression twists logic; it minimizes the consequences of a stigmatized death and denies any hope of possible recovery.

I once had an abscessed tooth, and in the absence of a dentist, I seriously considered trying to pull it myself to end the horrible pain. Each of us seeks to maintain a sense of internal integrity while still making a positive impression on others. We are driven by a fear of being discredited. Sometimes that means keeping secrets, especially when the concealed information is sensitive—a history of abortion, a positive HIV status, or sexual attractions.

Secrets are like abscesses waiting to be lanced so the pain will disappear. They are painful; they hurt when we touch them, but we can’t stop touching them. A secret that is at the center of our integrity creates excruciating pain. Secrets produce symptoms of worry, anxiety, and anger that pressure us to disclose those secrets for relief. We long for the momentary intense pain that comes with rupturing the secret like an abscess to release the pressure. We know that once it ruptures, most of the pain will disappear.

Concealment of sexual orientation may occur consciously or unconsciously. Monitoring the secret against societal norms requires considerable effort, constant vigilance, and behavioral self-editing. Although we may wish to disclose the secret, our need to make a favorable impression on others often overpowers our need to disclose. When we consider revealing that we are gay, we sense it will create a vacuum in our self-esteem, and we fear that this vacuum will be filled by all of the shameful, stereotypical characteristics we have internalized of what it means to be gay.

Secrets are like abscesses waiting to be lanced so the pain will disappear.

Coming out is an intimate disclosure that has the power to strengthen or destroy relationships. It defines oneself in a way that acknowledges and integrates feelings and desires that previously were unacceptable, thought to be immoral, and never revealed to anyone. For me, it was a process that began with a life of guilt, fear, and hiding, followed by a period of intense self-examination, and ended with the development of a positive gay self-identity. Although some would say a person cannot be self-actualized until he assumes a complete and open gay identity, many men who have sex exclusively with men say that goes too far. They believe that while disclosure is important, one can still feel actualized without disclosing his sexual identity in every aspect of his life.

In my interviews I commonly found that even though it may have taken decades for a man to come to his own acceptance of his sexuality, he often mistakenly expected his family to embrace it immediately. Families initially may be overwhelmed and unsupportive, but in my experience many learn to modify their own internal value system to incorporate acceptance of their family member’s sexuality. Sadly, some gay men and women have found their families completely unwilling to accept them. Their only alternative is to walk away and replace them with a family of choice composed of loving and supportive friends.

Due to the adverse social conditions that LGBTQ youth experience as a result of the stigma society attaches to their identities, suicide is one of the three leading causes of death for adolescents and a major public health crisis. Gay adolescents are four times more likely to commit suicide than their heterosexual peers.3 But in 2013 the CDC reported a surprising surge in suicide rates among middle-aged Americans while there was a relatively small increase in suicide rates among younger people and a small decline in older people during a similar period.4 Prevention programs tend to focus on suicide among teenagers; until recently middle age had been overlooked. From 1999 to 2010, the suicide rate among Americans ages thirty-five to sixty-four rose by nearly 30 percent with the most pronounced increases among men in their fifties, a group in which suicide rates jumped by nearly 50 percent.5 The rates of suicide are alarming but even so are likely underreported.

Evidence exists of increased rates of diagnosable psychiatric disorders and substance abuse in the LGBTQ community, but population-based studies of suicide in the middle-aged and older LGBTQ community are virtually nonexistent. The gay community resists discussing the subject of gay suicide because it fears that talking about suicide will reinvigorate the idea that being gay is a form of pathology. The possibility that sexual confusion and conflict about sexual identity might be a contributing factor to suicide in middle-aged LGBTQ people is rarely, if ever, considered.

One of the leading risk factors for suicide is feeling alone. One man in his fifties wrote to me that he was “torn up inside” because of his hidden feelings, but when a man came on to him sexually, “I beat the crap out of him.” He began to question what was wrong with him, but he spoke with no one about it. He then turned to alcohol for the next few years. He wrote, “I am sure there are other men out there who are in the same boat as me. Maybe together we could come up with a solution and help one another!”

We all prefer to be a part of a community that accepts and supports us, but for some, isolation makes that very difficult. In their 2000 study of gay and bisexual men and women past the age of sixty, Arnold Grossman, Anthony D’Augelli, and Scott Hershberger found that when people are part of a stigmatized minority, being in the presence of others like them had a positive effect on self-esteem.6 Many in the gay community who commit suicide do so while contemplating the public disclosure of sexual orientation and gender identity issues. Coming out in midlife is frightening enough, but it would be terrifying if there were no community in which to find support. Having someone to turn to is key, particularly for those struggling with same-sex attraction in middle age, but fewer resources are available for the middle-aged gay community.

Psychiatrists cannot predict who will commit suicide, but established criteria are used to assess risks. Risks include being male, being depressed and lonely, and abusing drugs and alcohol. Unresolved sexual identity issues heighten anxiety, loneliness, and isolation. All of this creates a fear that life is not going to turn out as planned. Because middle-aged gay men fear exposing their secret, they frequently resist seeking help.

Even when they live alone, elderly gay men often continue to have emotionally intimate relationships with others. Those who are isolated may have as much as 65 percent more depressive symptoms. Becoming a part of a community where you don’t have to always censor your speech or edit your behavior is remarkably liberating. It creates a feeling of finally coming home again. Grossman, D’Augelli, and Hershberger reported that within research subjects’ networks of friends and family of choice, the sexual orientation of their companions was less important than the freedom to be open about sexual orientation. But a supportive community will not seek out a mature man who finally chooses to come out. Finding that community will be up to him.

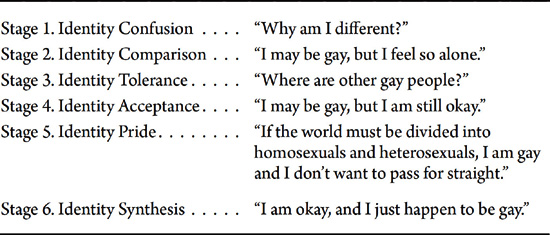

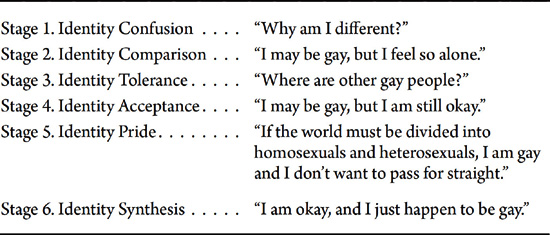

Several different theoretical models for the stages of coming out have been described. One of the most widely referenced is “Homosexual Identity Formation: a Theoretical Model,” put forth by Vivienne Cass in 1979 (see table 2). Cass wrote that because gay men and women are raised as nonhomosexual children in an antihomosexual society, their development creates a sense of internal incongruence between how these individuals perceive themselves and how they are perceived by others. According to Cass’s model, a need for internal integrity propels people forward through the various stages, and choosing to live with a difference between personal and public identities prematurely halts developmental progression.7

Many coming out models, including Cass’s, suggest that openly identifying as gay is a linear developmental process. It begins with an awareness of same-sex attraction emerging in early childhood, followed by typical timing and sequencing of certain milestones, and eventually reaching the final endpoint of completely coming out. These models have similar, distinct themes: tell yourself, tell your mother (who probably has already figured it out), and then tell the world. Another common theme is that coming out occurs only in a climate of alienation and shame, surrounded by forces that seek to suppress the truth. Often little support exists.

Table 2: Stages of homosexual identity formation as described by Cass

Earlier models imply that one size fits all, and that self-actualization only occurs when one moves through the stages in a regular and progressive way until reaching the point of living an openly gay life. In these linear models sexual development typically ends in the twenties, but always by age forty. An orderly series of ideal or typical stages are posited as the exclusive paths to recognizing, making sense of, and giving a name to emerging gay identity.

These models are useful as a heuristic device that simplifies a complicated process, but they tend to collapse individual stories into common feelings, common thoughts, and common events. They are problematic because they do not provide alternatives—something that I struggled with as a man who came out in midlife. Since my life did not comply with these theoretical models, I began to question whether or not I was gay rather than question the universality of the models.

Many MSM that I interviewed particularly objected to Cass’s fifth stage, “I am gay and I don’t want to pass for straight.” Whether they are primarily gay- or straight-identified, many disclose their sexuality to varying degrees depending upon the situation. They may be completely out with gay friends, out to a few close friends and family, but not at all out to other family members or at work. Those who have an early initial awareness and acceptance of being gay progress through development before having much same-sex experience; these men self-identified early on as gay, and they completed their sexual development as young men. For a wide variety of historical, economic, and social circumstances, other men come to accept their being gay later, sometimes much later, in their lives; many of them have had considerable clandestine sexual experience with other men. Men who choose to come out when they are more mature develop their gay identity later. When gay men have not resolved their internal fears of being gay, they experience low self-esteem, greater social isolation, and greater health risks.

Because earlier models for coming out underemphasize sociocultural factors, this stage-sequential framework for gay identity development is being replaced with a hypothesis that multiple trajectories exist for gay self-definition. A trajectory describes how a projectile moves through space—a rocket in flight, for example. Objects moving through space have both individual characteristics and properties in common, but they must obey the laws of physics; they require energy to move them, and their environment influences the progression of their flight. Each object is unlike any other, and therefore it must follow its own unique trajectory.

Rockets are launched only after their propellant is fired; until then, they are governed by the law of inertia. People maintain the status quo unless compelled to alter it. They can’t imagine a better future. Future options and outcomes are fuzzy and ill defined. Some choose not to come out because they expect that they might lose much more than they would gain from a future that they can only vaguely visualize.

Some men believe they have always known they were gay. Because the world is a different place now, some young people appear to blast right past all of the milestones, such as admitting their same-sex attractions to themselves and others, and some are completely out in early adolescence or even before. Others who have an early knowledge of their sexual orientation withhold disclosure, delay same-sex experiences, and remain closeted until they are older and have detached from their families. Some younger men may find it easier to come out when they are further along in their education and career. Financial independence provides greater access to a wider range of social options. These men may reach coming out milestones in a more sequential way. Others postpone dealing with their same-sex attractions until midlife or beyond because they have been unable to resolve the dilemma of who might be hurt if they reveal their secret as opposed to how they might be hurt if they continue to conceal it.

Each stage of the earlier models of coming out such as the one described by Cass has a benchmark. Some gay activists insist that those of us who move through the stages grudgingly or stall before the endpoint are defective. When I was in my thirties, I read about the stages of coming out and I discovered that the suggested age for completing all stages was in the mid-twenties. Again, I thought, “I can’t be gay. I’m over thirty-five and I’m only in stage two.” Although I “just went gay all of a sudden,” I didn’t exactly throw open the closet door, jump out, and shout, “I’m gay!” My progress toward a public and personal gay identity was halting and tortuous. I didn’t come out, I inched out—backward—often waiting to be asked if I was gay rather than confronting the issue head-on.

The trajectory for coming out, as well as the associated milestones, is highly variable. And as I learned firsthand, it doesn’t occur sequentially. Some milestones may never be reached, some may happen more than once, and no endpoint can be identified where all of the work of coming out is finished. Most people, including my patients, for example, presume that I am heterosexual. The more men I spoke with who came out in midlife, the more my own story was repeated back to me. Deciding when and to whom to come out is a process that never ends. The following factors can affect the timing of coming out:

• Parents and closeness of family structure

• Age, gender, and level of maturity

• Socioeconomic group, profession, and education

• Race, religion, geography, and culture

• Evolution of societal values

• Idiosyncratic life experiences

In 2010, at a Las Vegas regional meeting of Prime Timers Worldwide, a group of mostly mature gay and bisexual men, one of the men stated he had never been to a “gay” event before. He announced to everyone he met in the hotel and casino that he was attending “a convention for bisexuals.” He was in his mid-to-late seventies, had been married for about forty years, and lived in a small rural town in a rural, Western state. In the past, when he had traveled out of town he would be drawn by powerful urges to have sex with a man, and for many years, he lived a “down low” life.

People maintain the status quo unless compelled to alter it. They can’t imagine a better future.

He only began to come out following his wife’s death. He believed that everyone is bisexual. He had parked his car in the bisexual parking lot, because accepting he was gay would have been driving too far and too fast in the gay lane. I briefly considered labeling myself as a bisexual, accepting that I had some attraction to men while still desperately clinging to my marriage and heteronormativity.

For many men, geography figures significantly in coming out, especially for middle-aged men who have already established communities for themselves, albeit in their heterosexual roles. In 2013 in an article in the New York Times Seth Stephens-Davidowitz wrote that on Facebook, about 1 percent of men in Mississippi who list a gender preference say that they are interested in men; in California, more than 3 percent do.8 Are there really so many fewer gay men living in less tolerant states? For some gay men in rural and suburban areas, their same-sex activity has been primarily a weekend, leisure activity, rather than a full-time identity. Gay men living outside of urban areas more frequently pass as heterosexual, are more fearful of exposure, anticipate more intolerance and discrimination, and have fewer same-sex friendships and sexual encounters.

My own process of coming out certainly did not fit the molds I’d found while exploring my own inner conflicts. I was living out the dictates of my culture as the protector and provider. I fell rather easily into my professional identity. I cannot pinpoint when my marriage to my wife, Lynn, began to fail, but long before I began to question my sexual orientation, I had doubts about my skills at being a good husband and father.

As Lynn and I agonized about the possibility of divorce and breaking the most important commitment either of us had ever made, we searched to reconcile the asymmetries of our potential losses. Neither of us came from a family where anyone had ever been divorced. Every person in our small Nebraska hometowns—about twenty-five miles apart—could have disapprovingly named every couple in town who had been divorced. As a child, I had a younger friend whose parents were divorced and whose father was detached. I could not understand how that could happen. My mother was a single parent because my father had died, but I wondered how anyone could ever lose his father because of a stupid decision his parents had made.

Each Christmas the studio where my daughters studied dance put on performances of The Nutcracker. They always needed men for the first scene where the Stahlbaums host a lavish party around a tall Christmas tree. Shortly after meeting Roberto, and long before considering my divorce, I decided to audition and was given the role. At a postrehearsal party for the adults in the cast, I stalled until the other guests had left. I wanted to talk with the rather effeminate younger man who had hosted the party. As we sat with a glass of wine, I told him I wanted to talk to him because I thought I might be gay. He seemed surprised and responded, “I don’t know why you would want to talk with me about that. I’m not gay!” I had barely dipped my toe into the coming out pool only to find it filled with hot lava.

Prior to meeting Roberto, I had encouraged Lynn to see a counselor with me to see if we could rediscover some meaning in our relationship. What we had was not enough for me, and it didn’t seem to be working very well for her either. After I fell in love with Roberto, I discovered the possibility that I could have something more. Then one evening Lynn brought me some pages she’d printed off my computer. She had discovered some of my writing that journaled details of my relationship with Roberto. She said nothing, just handed the papers to me. A very big abscess was about to be drained.

I felt relieved that my secret was out, but confused about what to do. I knew that I wanted to leave the marriage. How would I tell my mother, who loved Lynn as much as she loved her own daughters? How could I tell the kids that I’d failed at being a father, and I was leaving them when I knew how painful it had been for me not to have a father? Was I putting everyone through all of this pain just for sex? What I had discovered was that I would never be like those other men I was pretending to be. Somehow a barrier had been erected between those other men and me; they were one kind of man and I was another. But now it no longer mattered. I began to mourn everything that had given my life definition up to that point.

I loved my wife as much as I was capable of, yet through no fault of hers it wasn’t enough. I wondered if she knew it, too. I had always promised to give my children the father I didn’t have, and I had participated in every aspect of their lives, from dirty diapers to Suzuki violin and piano practicing and lessons. I suffered through every dance recital. I love my children more than I ever thought it possible to love another person, and my children were the center of my life. How could I set that aside? I knew that being a good father and being a good noncustodial parent are not equivalent. I was considering giving up being an on-site father because I knew I had discovered that I was capable of experiencing loving a man in a whole different dimension than I had loved their mother.

I didn’t tell my mother I was gay; she asked me. Shortly after I had separated from Lynn and moved to Des Moines, she visited me, and before her visit Roberto and I made a plan to test her out by having him drop by my condo. After she went home, she wrote me a brief note: “After our visit, I got to wondering if you might be gay. Love, Mom.” I confessed much more than my family needed to know in an eight-page letter that I copied and sent to my brother and sisters.

I was frightened and uncertain about coming out, but with each step I began to feel more relieved, exhilarated, and validated. I anticipated that some friends, family, and colleagues would be shocked, confused, and even hostile. I was certain some would accuse me of exploiting my wife and destroying my family. Those were accusations I was prepared for—I had already made them. My trajectory had progressed through telling myself I was gay, confessing it to a few others, and finally telling my family. It hadn’t gone as badly as I’d expected it to. But I was only beginning to make a new way for myself professionally, and I thoroughly believed that being out professionally would undermine my position of leadership in my new job as medical director of psychiatry at one of Iowa’s leading hospitals. I led a quiet life as a newly out gay man.

All of life’s important decisions are made without enough information, and coming out is no exception. We make our decisions based upon predictions about how our lives will be affected by the possible outcomes. A decision to change must carry with it a substantial chance of achieving something considerably greater than what might be lost, an economic principle called loss aversion. Those of us who have waited to come out until later in life typically have done so because we fear losing something very important in our lives, but the things we value—the things we most fear losing—are uniquely our own.

One of the men I interviewed was a man I’ll call Jason McGee, a twenty-seven-year-old man who lives in rural Alabama. He described himself as a black American rather than an African American. He said, “The South expects certain things of you as a man, and being gay ain’t one of them. Down here, people like me ain’t gay or homosexual; we are queers and fags. For a Southern black man, being called sissy, fag, queer, or homo is one of the biggest disgraces ever.” According to McGee, being labeled gay brings shame to your family and you are isolated because of it. He believes that being black and queer would almost certainly make him the victim of a hate crime. He said, “I’m masculine, so no one knows who I don’t want to know.”

McGee came from a loving and intact family. He considered his father to be his friend as well as his dad, and he was not treated differently within the family. His parents seemed to accept his excuse that he doesn’t date because he’s busy with school and a job. His brothers were in long-term relationships with women and had given his parents grandchildren. He regretted that he would not be able to. McGee had several gay cousins, although only one of them was out and he lived far away. Starting at age eleven McGee began participating in sexual play with one of his cousins. They started by wrestling with each other, and one day McGee ejaculated but didn’t understand what had happened. They continued to explore sexual play, but it always began with wrestling. Sometimes they were naked. Later they began to masturbate each other.

All of life’s important decisions are made without enough information.

McGee was a Baptist who said he loves God and loves his church; he belonged to a congregation composed mostly of white people. Although he saw himself as gay, he was out to no one except his brothers, and only because they confronted him when they discovered some gay porn on his computer. They asked him if he could change, and when he said that he couldn’t, they accepted him. He had no intention of coming out to the rest of his family. He believed coming out would mean letting go of so many people he loves, in both his family and his church. He decided not to come out because, he said, “I don’t want to bring pain to my family and friends—myself, too.”

At times McGee struggled in his church because “it hurts to hear [homosexuality] preached so hard against.” He said some members of his church can’t see past what their eyes show them, but he did not believe himself to be perfect and did not expect them to be perfect either. He said that he reconciled the issue for himself, quoting Romans 3:23: “For all are sinners and fall short of the glory of God.” Then he said, “All are sinners. All. Everyone, not just gays. All. In God’s eyes, no one’s sin is worse than another man’s sin. People are born in sin, so you can be born gay, as I believe I was.”

He described his sexuality as complicated, especially because he was primarily attracted to white men over the age of forty-five, an attraction he discovered through erotic feelings toward his male teachers. He had had a limited number of sexual partners as an adult. He was not looking for a relationship, but neither was he avoiding it. He said, “I don’t act out my sexuality, except maybe online, and even then, I am not feminine by any means.” He said that his sexuality doesn’t define him or what he does because he doesn’t let sex rule his life.

Although McGee had come to peace with his sexual orientation, he was uncertain of what it meant for his future. He wanted a relationship and children. He said, “I look around and I see the type of man I like everywhere, and yet I can’t have any one of them. I see my friends with wives and girlfriends and I just go back home to my closet.” He remained uncertain how to handle the issue of coming out. He said he had talked with other black men who felt that they have more freedom and more options after having come out, but for McGee coming out was not a priority. He said, “I’m still in the closet because I can’t see what good coming out will do in this area. I hear about the free feeling you feel once you’re out, but hell, I don’t want to be alienated or hated either. There ain’t no big gay community for support here. It’s every man for himself. I get along fine, but it is still a challenge when you realize you’re alone.”

A few years ago I met another African American man at the gym. We often worked out at the same time and frequently ran into each other in the dressing room or sauna. Over several months we talked about a lot of things and we were in agreement about most political and social issues. Since only about 3 percent of the population of Iowa is African American, I had not had many opportunities to develop a friendship with a black man. Then one day he said to me, “We’ve got to do something about the fucking queers in this place.” Although we’d never talked about it, I had assumed he knew that I was gay. I was devastated, and I went over to talk with one of my gay friends who was there. I told him what had happened and also about my experience in the Lutheran Church. He said, “You know, it isn’t like that everywhere,” and he invited me to his church, where all are welcome.

Although society is changing, coming out still means running the risk of losing heterosexual gender role advantages, friendships developed in the heterosexual world, and social status. Men who haven’t come out have hidden a fundamental part of themselves because they fear losing love and respect and being abandoned and alone. Some simply fear exposing an imperfect masculinity. Although such negative outcomes can be quite painful, we overestimate the intensity of our feelings of loss and how long those feelings will last. We fail to learn from prior experience that the repercussions from revealing our secrets are almost always less than we anticipate. We underestimate our power to transform negative experiences into positive ones.

Ultimately the strength of a person’s support system is the most significant influence in how coming out unfolds. Although the net impact of revealing secrets is typically more positive than negative, and usually more positive than anticipated, the benefits of revealing sexual identity certainly are not guaranteed. Personal revelations are significantly influenced by the response we receive from others. In considering whether or not to come out or how and when to disclose sexual orientation, it is important to develop strategies that are likely to result in positive responses from a network of supportive friends.

As I got older, I felt an increasing sense of urgency to deal with my hidden same-sex orientation. The same was true of the men I interviewed who came out in middle age; time passes quickly, and life begins to seem too short to start over again. As a psychiatrist, I have learned to tell my patients who are dealing with significant life conflicts to simplify the decision-making process. We have only three options: change it, put up with it, or get out. In most cases one of those three options can be eliminated immediately. Since attraction to someone of the same-sex is not going to change, a married man is left only with suffering through it or getting out. Acceptance generally evolves in a positive direction, even when the initial responses to coming out are unfavorable. Change does occur, albeit slowly. Relationships that were once thought to be lost can improve over time as family and friends begin to reconcile their homonegativism with their positive feelings for the gay man.

However, let me be clear; sometimes things really are as bad as they seem. Some of my closest friends from my heterosexual past disappeared from my life completely. For them, change felt impossible, and they reacted by getting out. While criticizing them for being homophobic and judgmental is easy, the truth is that I had never really let them know me completely.

In the process of interviewing for this book, I discovered that many, if not most, mature gay men experienced same-sex attraction as adolescents. But for some, the significance of those early same-sex feelings was not recognized until later; sometimes only after coming out did they really understand those attractions. I have also discovered, however, that many heterosexual men have had very similar sexual attractions as adolescents, although they were reticent to acknowledge them or interpreted them differently. Both gay and heterosexual men spin those past experiences, attaching significance as suits their current sexual identity.

In Bridge of Sighs Richard Russo writes, “But at some point, all of that changes. In our weariness we begin to sense the truth, that more doors have closed behind us than remain ahead.”9 When I reached midlife, I didn’t find just one closet door out of which to come out. I was confronted by a series of complicated and interlocking doors. There were doors for my spouse, my parents, my kids, my siblings, my coworkers, my friends, and my religious community. I would knock on one door, only to find a solid wall. Other doors I could only peek in, and then realize I must not go inside. Some doors I knocked on over and over again with no one answering. When we come out we don’t just open one door and walk through; we move through each of those doors through a process of negotiation.

Coming out professionally remains a significant issue for many gay men. Federal laws do not safeguard against employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, and in 2016 over half of the LGBTQ population live in states that prohibit employment discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.10

A study by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation released in May 2014 indicates that most LGBTQ employees (53 percent) nationwide are closeted on the job. Despite significant strides among the Fortune 500 and other major businesses implementing inclusive employment policies and practices, consistent legal protections are not afforded to LGBTQ people state to state. Many LGBTQ people feel unable to talk freely to their coworkers about their partners, and even more don’t feel comfortable bringing their partners to corporate social functions.11

When I relocated to Des Moines after my divorce, I moved only thirty miles away, but it was an entire world apart from where I’d been while I was married. I knew no one and for a while couldn’t even remember my own phone number or the names of any streets, save the one I lived on. I was starting a job as medical director of psychiatry at one of Iowa’s largest hospitals. My grasp on my role as medical director felt very tenuous. Coming out as gay to the other psychiatrists seemed as if it would release my grip all together. I threw myself into the job, working seventy hours a week. It also proved to be a great escape from my feelings of failure as a husband and father, and left me little time to think about my loneliness and how much I missed my kids. As Justin Spring wrote in Secret Historian, “Normal men do not often have to choose between love and a career. . . . But the homosexual, it seems to me, often finds himself in a place where the choice between a career and love seems inevitable.”12

I definitely overestimated the consequences of being out professionally, and I am fortunate to have experienced very little in the way of outward discrimination. Only once did my sexual identity seem to be an issue professionally. I had interviewed for a medical director position at a major health system in Indiana. We had completed negotiating the contract, and I was all set to sign. Out of the blue the recruiter called and said the hospital had decided to stop all negotiations and discussions about hiring me. No explanation was given, and in my opinion, none was necessary.

The primary task of coming out is to redefine one’s identity so that what was once seen as an aberration is no longer seen as disgraceful. Heterosexuals don’t have to declare their sexual orientation. Men who are “undetectably gay” often encounter the presumption that they are heterosexual. I am frequently asked, for example, “How’s your wife?” Until recently most of my patients didn’t know much about my personal life, and for a long time that made it easy to pass as heterosexual, something I welcomed. At what point, I have asked myself, and to what degree, should I make a commitment to publicly declare my sexuality? As I became more comfortable as a gay man, I began to ask myself, “Does social justice require that I correct everyone when they make that mistake?”

Being gay does not really tell us much about who we are because there is no single gay identity and no final step in a developmental process. For many, developing a gay identity is a nonissue, and as one matures, sex drive diminishes as the central organizing force of one’s life. As men become older, I found in my interviews, they begin to distance themselves from an all-encompassing gay identity and say, “I’m just me.” Gay identity is integrated with all other aspects of life, including relationships with family and employers; involvement with church, community, and political organizations; and committed Romantic relationships.

Mature gay men refuse to be molded into a universal gay identity, just as they once struggled to be free of the stamp of heterosexual identity. Unlike a rocket, each of us has the capacity to choose our own destination and the trajectory that gets us there. No matter when we confront our sexual identity, as a teenager or in our last decades, we all evolve throughout our lifetimes. Harold Kooden, in Golden Men: The Power of Gay Midlife, wrote that each man must direct his own advancement through the sexual development process. By taking more responsibility for his own history, a gay man has a deepening sense of active participation in his life that reduces his feeling of being overwhelmed and out of control. Kooden states that older gay men who are self-accepting and psychologically well-adjusted adapt well to the aging process.13

Being gay is not something anyone seeks or plans. In most cases we would have wanted something we once thought of as better, that is, until we accept that what we have is pretty damn good. We are individuals. Each man who has sex with men must direct his own self-development. We are launched into this world with a presumed heterosexual flight path, but the course our lives take is influenced as much by our own composition as that of the world around us. Eight of the respondents to my survey of mature MSM were over eighty years old. Four of them either came out or were outed in their eighth decade of life. Their life stories defy the universality of stage-sequenced coming out. Our lives evolve as the deniable becomes undeniable. There is no single identity, no single trajectory. No one else can live our lives.