City

I’ve been drawing the City of London since the fifties. I began by making wood engravings for Christmas cards, calendars and posters, and later, watercolours for hanging in City offices and later still, in the eighties, for a book of my own. Around 1999, for an exhibition, I drew the people crossing London Bridge on a chilly morning rush hour and afterwards went to a now-vanished café at the end of the bridge for a warming cup of tea, hardly registering the only other customer who was too tired and shabby-looking to even notice until he got up to leave just as I did, suddenly realizing he was my own reflection.

By getting to know the City when it was still largely Victorian, I grew to notice and like the contrasts between the beautiful churches and public buildings from the seventeenth century onwards to Edwardian times. I first saw its historic street names like Poultry and Fish Street while wandering about exploring with my son when he was young, and noticing the old confusing City ground plan which survived the 1666 Great Fire of London and Wren’s attempts to rationalize it. These historic streets and Wren’s and Hawksmoor’s churches are now getting buried amid the tall new glass and steel buildings. But the new buildings, with their clean and often simple outlines, have their own beauty and allure, their glazed surfaces reflecting those of their neighbours as if in an open-air hall of mirrors.

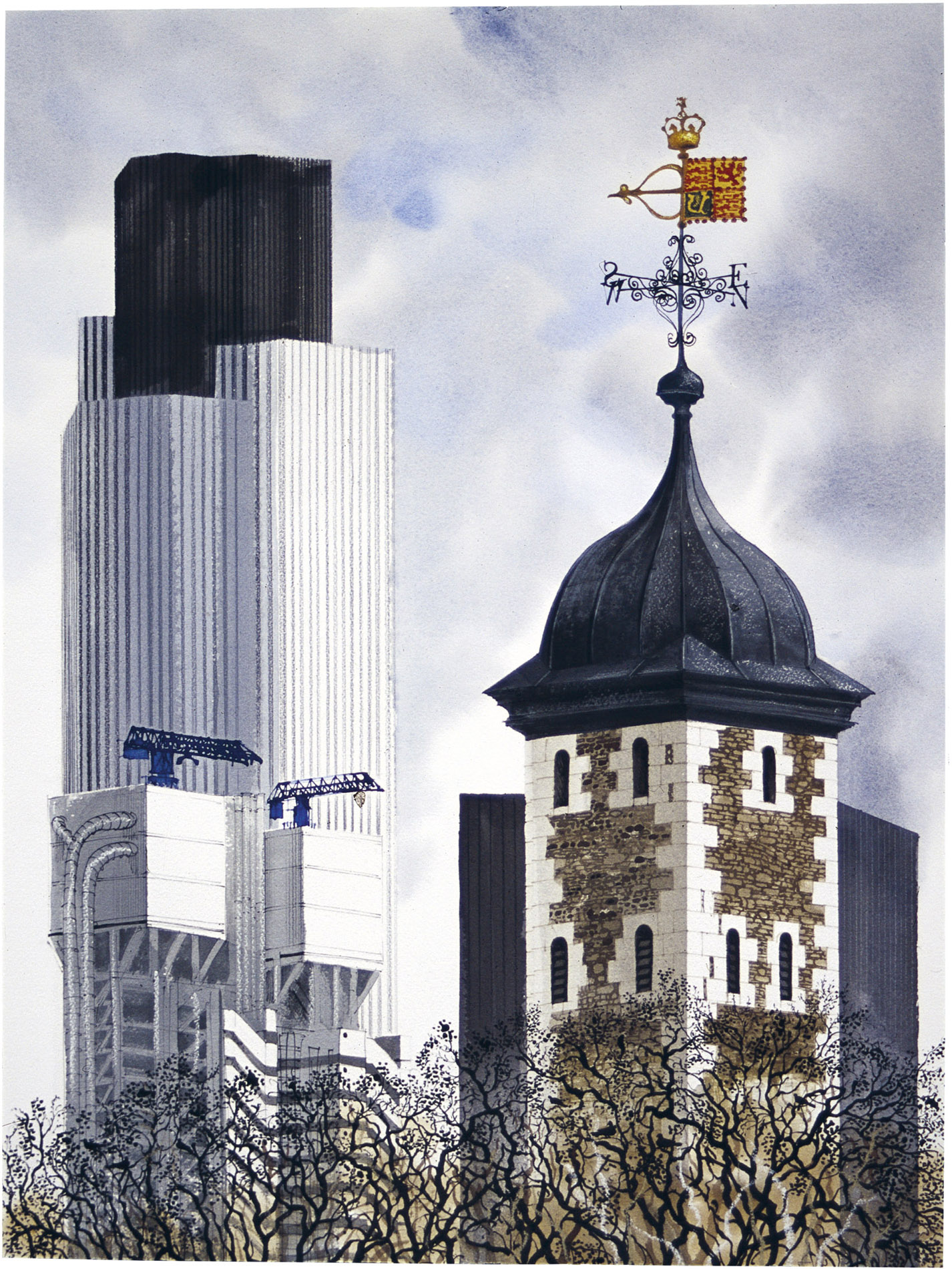

St Giles-without-Cripplegate is a striking City remnant within the Barbican. St Giles was the patron saint of lepers, beggars and the disabled. The church was gutted in the Blitz but later restored. The City’s first high-rises, easily identified by their projecting balconies, were the three tall Barbican tower blocks.

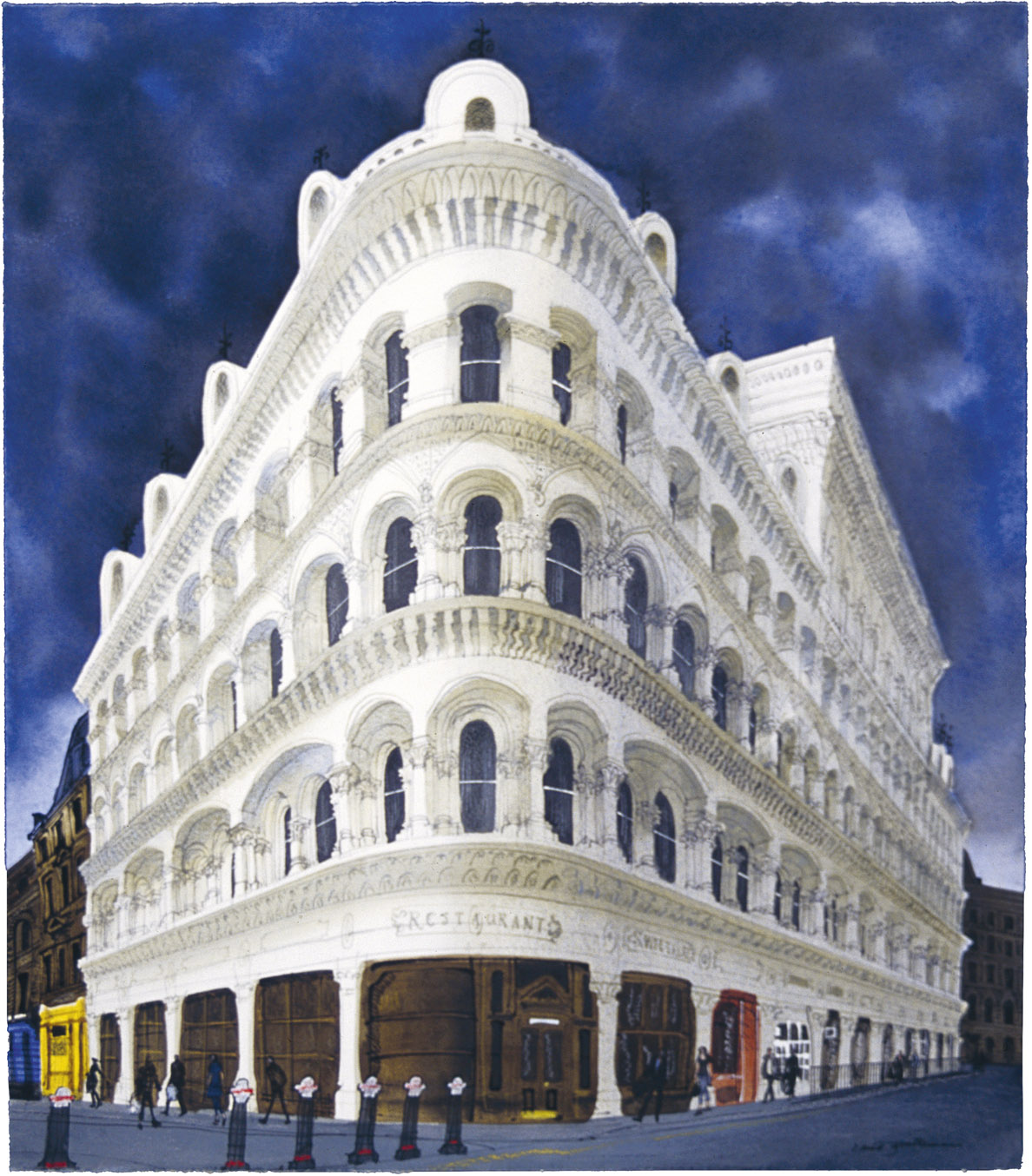

This corner building in Queen Victoria Street reflects Victorian detail, repetition and a heady suggestion of wedding cake. It had just been restored and repainted when I drew it but it needed a dark sky to dramatize it.

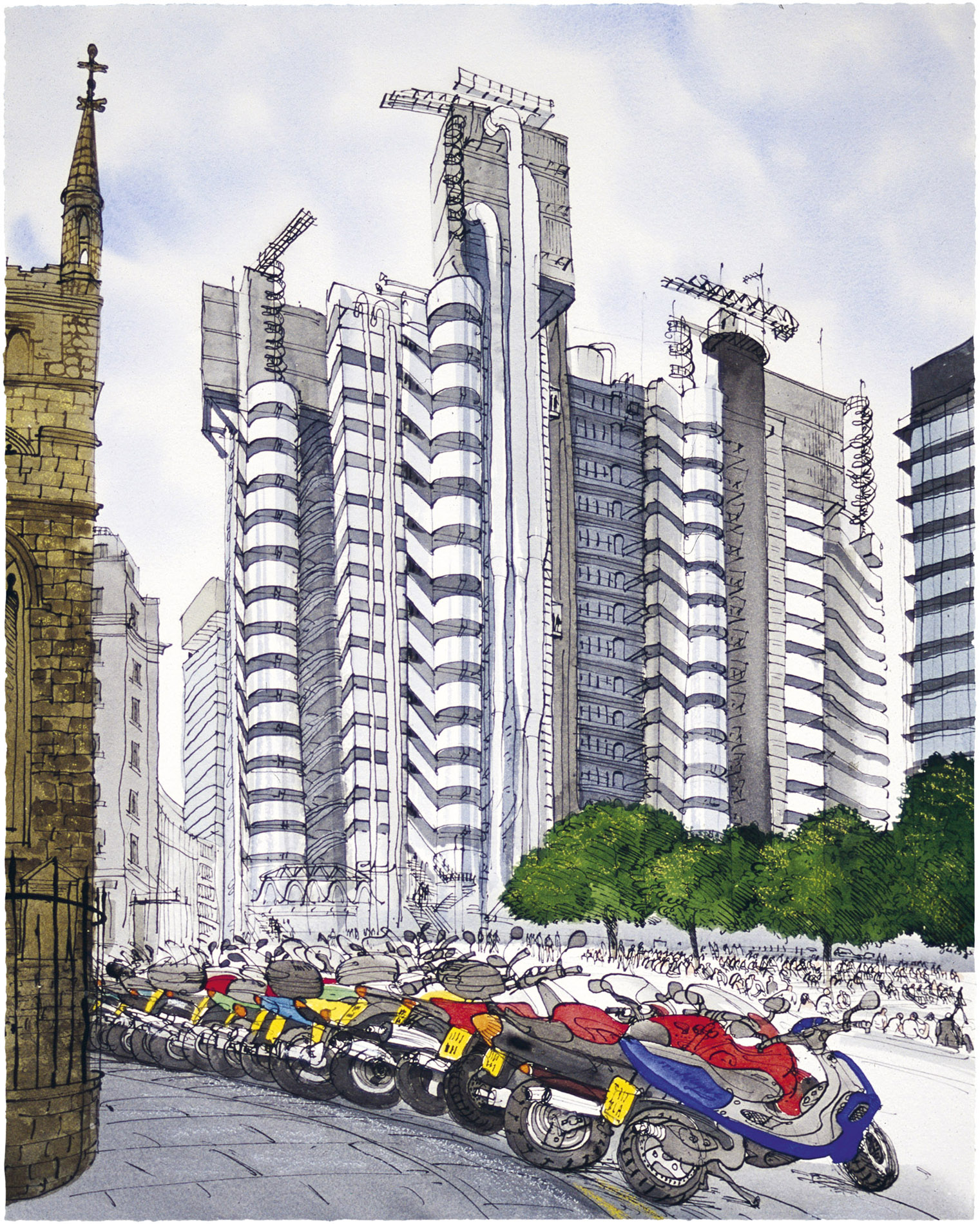

The trio of buildings here were each skyscrapers or at least high-rises in their day. NatWest was the first of the City’s tall office blocks; its hexagonal ground plan and section conveniently echoed the company’s logo. Lloyd’s of London was designed by Richard Rogers with the same inside-out characteristics as the Pompidou Centre in Paris, which Rogers had previously co-designed with Renzo Piano, later the architect of the Shard. The corner tower of the White Tower, the old keep of the Tower of London, now looks comfortingly white only in certain lights or when floodlit.

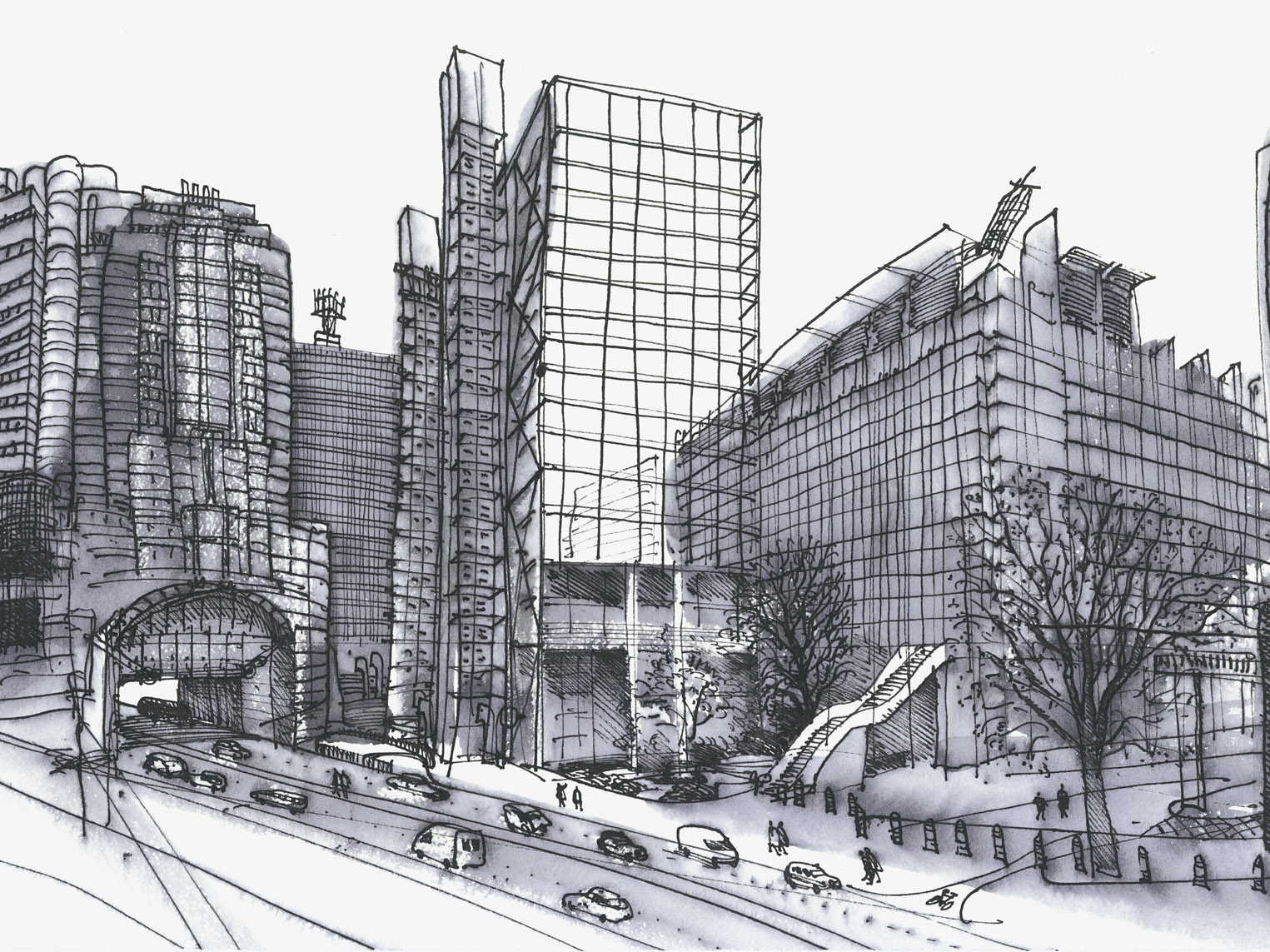

In 1984 a friend who worked there invited me to make some drawings from the top of an early and moderately high-rise office block at 20 Fenchurch Street, which has since been replaced by the Walkie-Talkie. I made the drawings from the terrace surrounding the executive suites where luncheon tables were being laid just behind me. The sketches show a now-vanished City as it was before the arrival of the Gherkin, Walkie-Talkie and Shard – a place that would be unrecognizable now. The NatWest Tower and the beginnings of the shiny new Lloyd’s of London were already there, but only a few cranes could be seen compared with the cluster around St Paul’s two decades later and the myriads there today.

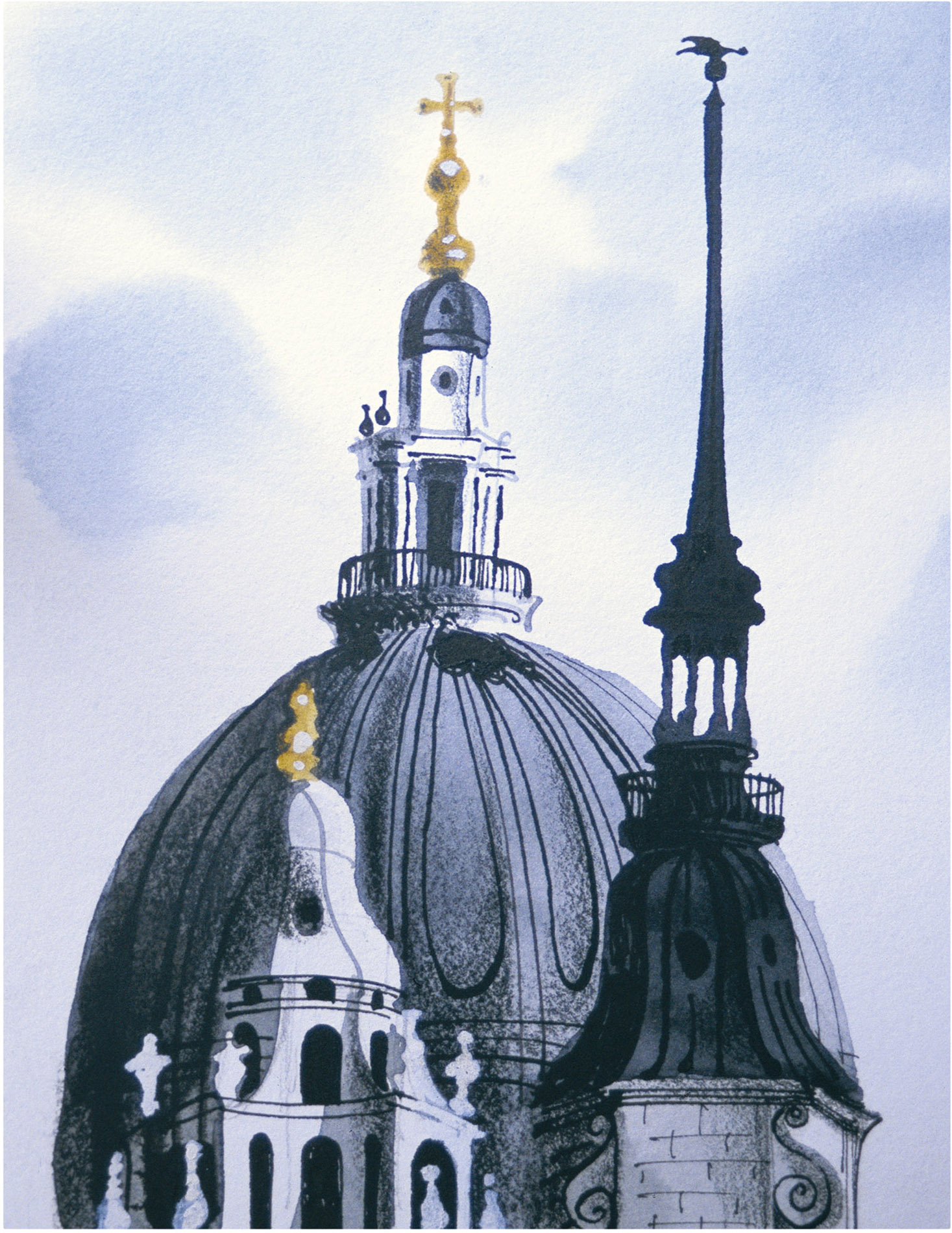

In the late nineties, while painting for a millennium exhibition, I looked afresh at the transformations in and surrounding the City and was struck by how familiar landmarks, like those in the watercolour here, were gently slipping out of sight. Nearby, the immense new office blocks spreading over London Wall were turning people and traffic alike into insects. The drawing below was made with a fountain-pen ink, which flowed better than Indian ink but spread into the drawing when I brushed washes of tapwater across it – not as it turned out disastrously, but unpredictably and quite usefully.

Commissions have led me to various contrasting subjects, ceremonial, professional or manual.

The city is now full of shiny metal.

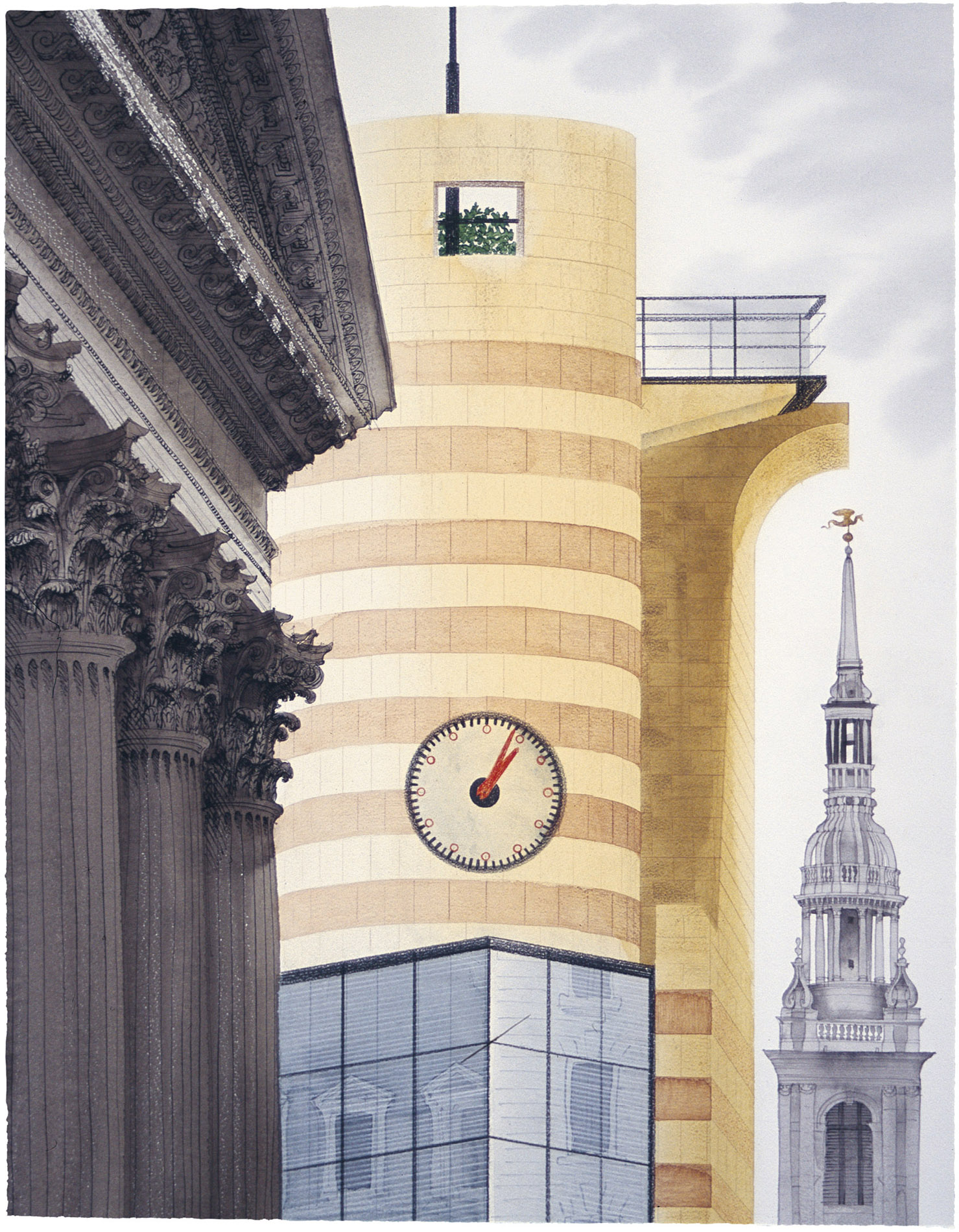

These images reflect the contrasts of style, media and technique, between the quickly drawn pen-and-ink sketches with watercolour added later and the larger and more diagrammatic or poster-like picture here, showing three different architectural styles: George Dance’s classical Mansion House façade and James Stirling’s No 1 Poultry, with Wren’s steeple of St Mary-le-Bow in the distance.

Right: Mansion House, 1999

Distance brings things close to each other – high-rise housing and commerce, the eighteenth century and the twenty-first, stone and steel. The City streets are now thronged with visitors as well as workers but Sunday morning is a good time to look at them when everything is relatively empty and quiet.