Canal I

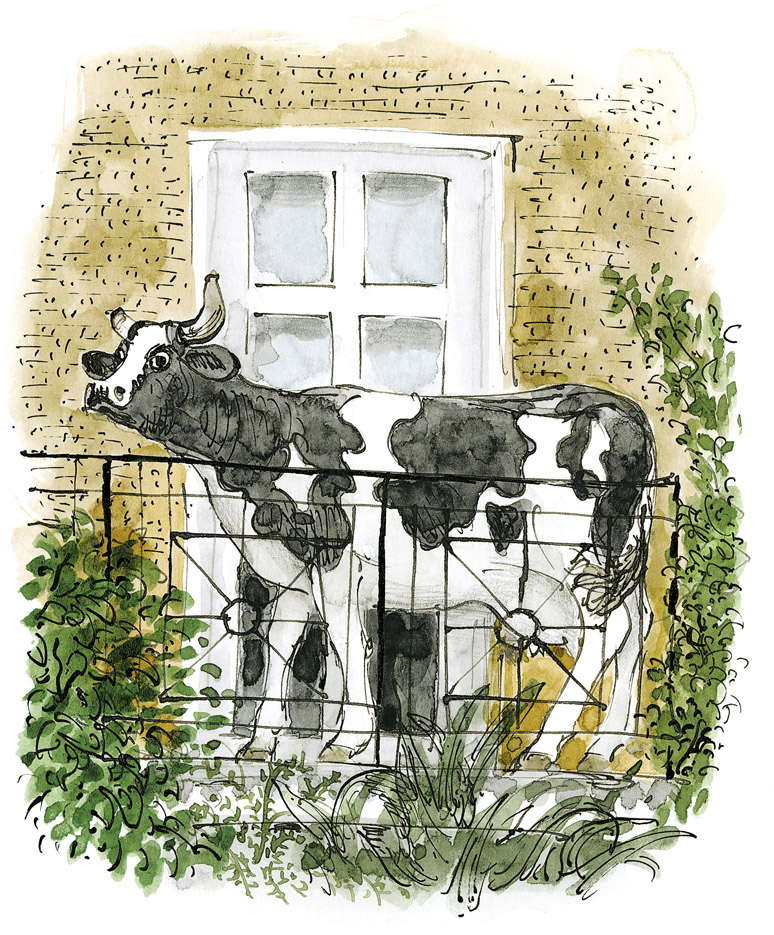

At the edge of Stables Market lies the Regent’s Canal. It stretches westwards and upstream from a heavily built iron bridge over Camden Lock. There are splendid views on either side, and usually crowds of people on both sides of the bridge enjoying the scene and photographing themselves and each other. I love the walk upstream from the Lock towards Regent’s Park and the Zoo, passing the 1890s and 1930s classic modernist Gilbey warehouses, and under the Pirate Castle Club bridge to a stretch of the canal where children learn how to paddle kayaks. Here its towpath has widened out to become a sunny place to rest or picnic on, before leading one under the main west-coast railway line from Euston to Glasgow (along which, earlier in my time here, steam engines would pass constantly, depositing grains of soot onto our window ledges). On the first-floor balcony of one of the villas that line the canal a life-size black-and-white cow stands motionless; from this point on, the scene turns quickly from post-industrial to domestic, green and rural. The most idyllic stretch of the canal is beyond the Zoo, where it is flanked on both sides by narrow but dense woodland, dark and romantic, and conventionally pretty to draw or paint.

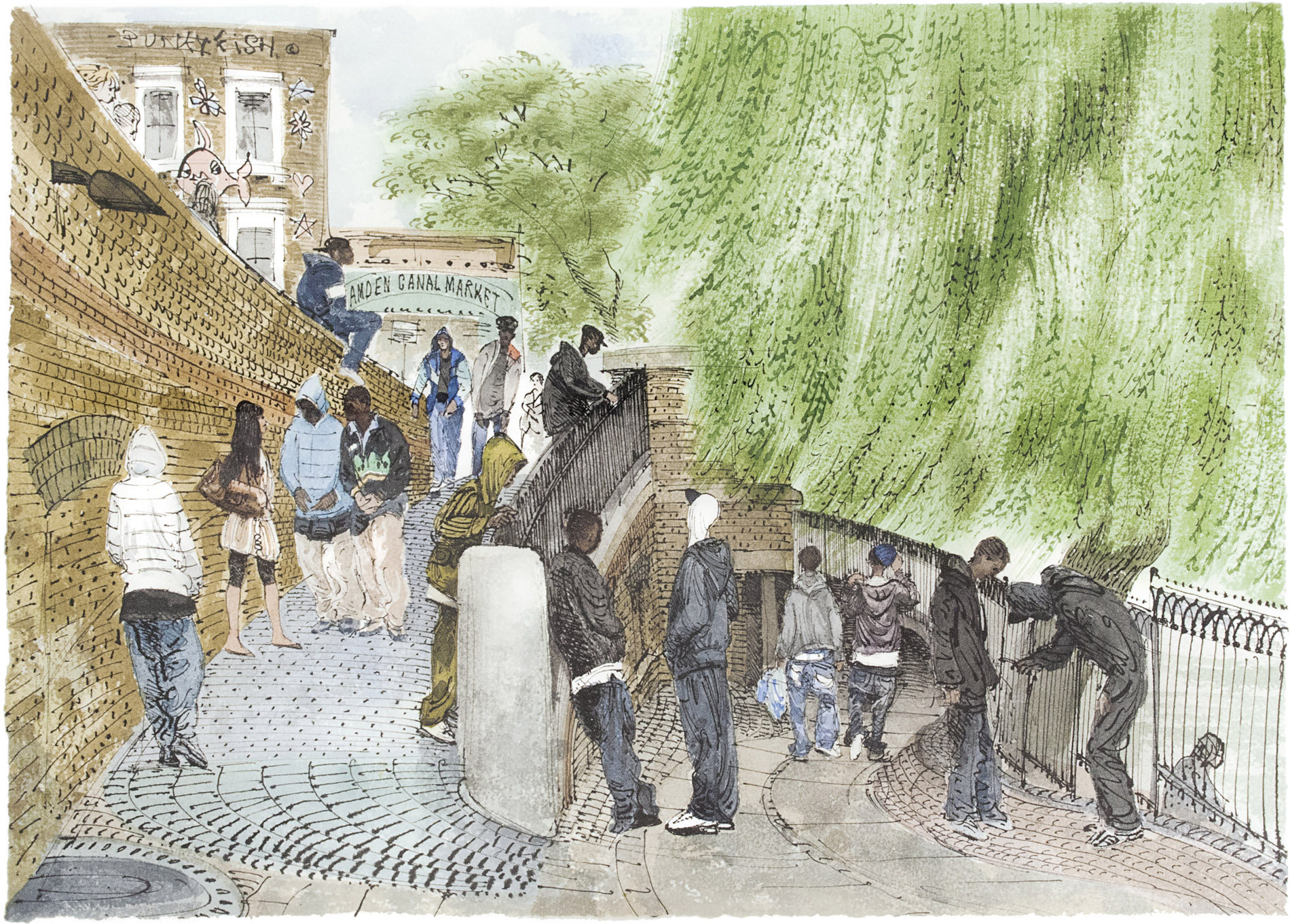

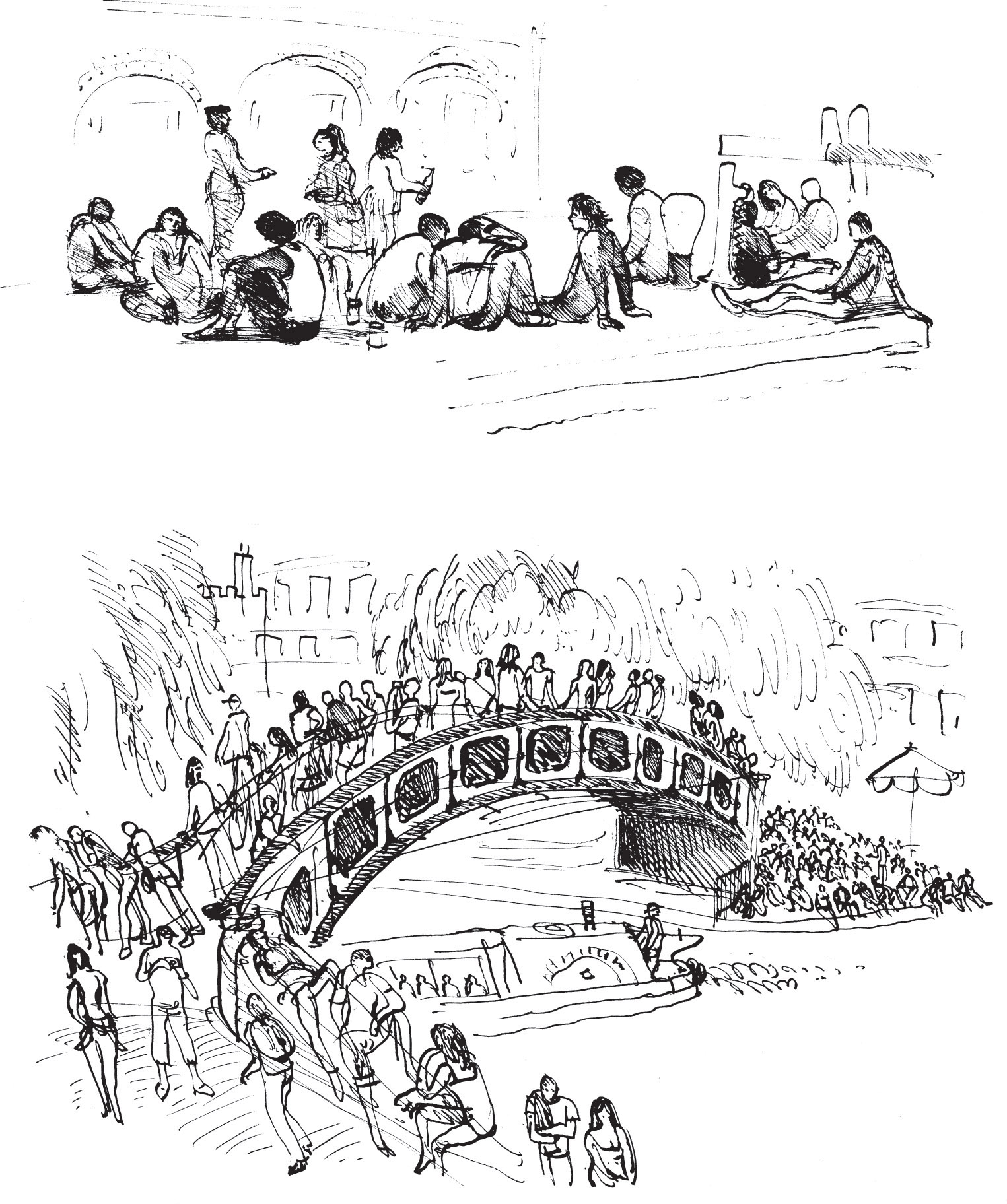

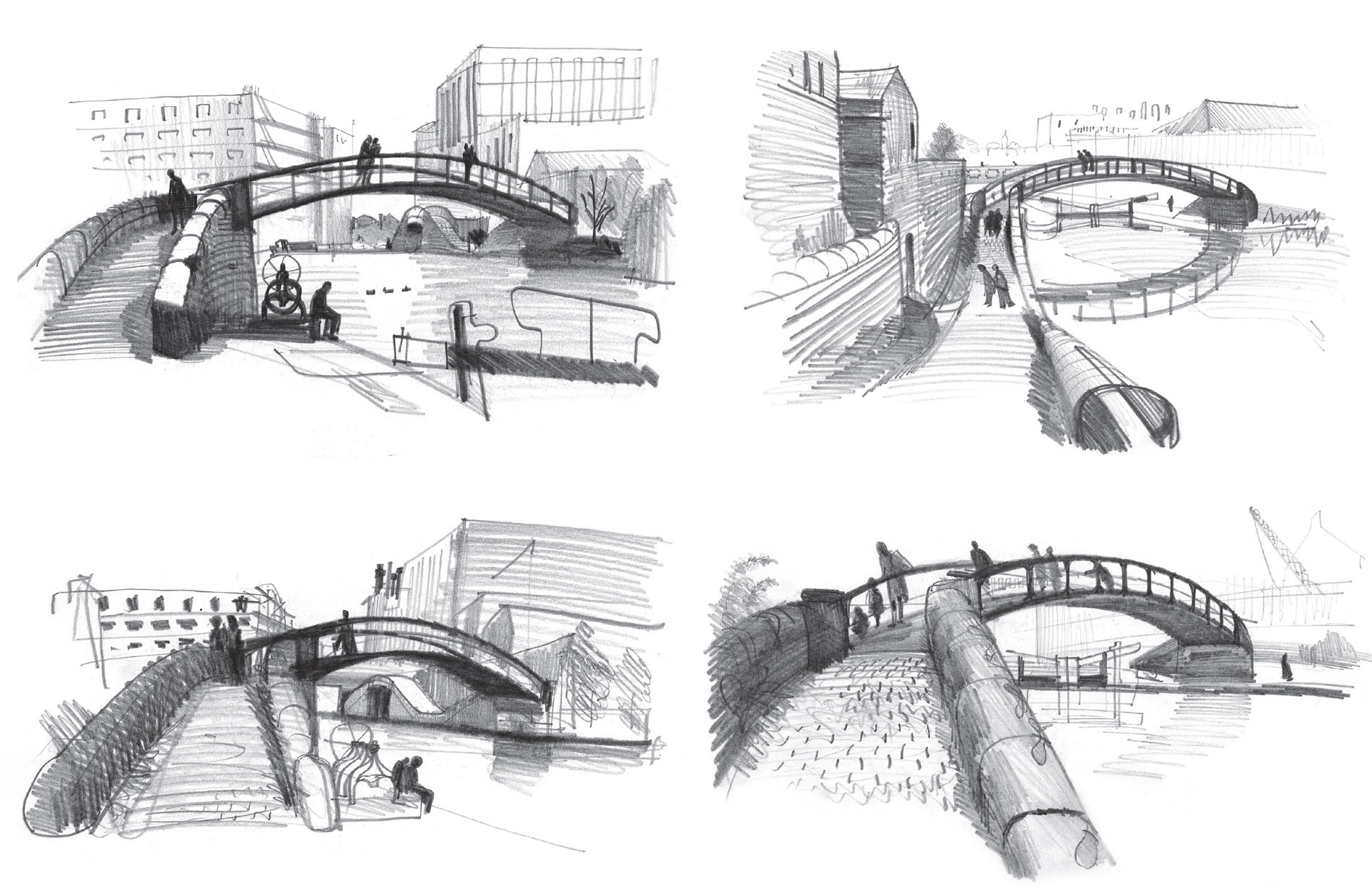

Pen-and-ink drawings of the Roving Bridge and Dingwall’s Dock where Stables Market and the Regent’s Canal interlink, the bridge and towpath, and people in the square where the barges dock. The dock’s original purpose was to be the interchange between canal and warehouses, whereas its role now is feeding, watering and captivating today’s hordes of young and international visitors. I try to draw from inaccessible or protected places – on a bench or at a café table, in a doorway or a corner or just with my back against a wall – because talking is distracting.

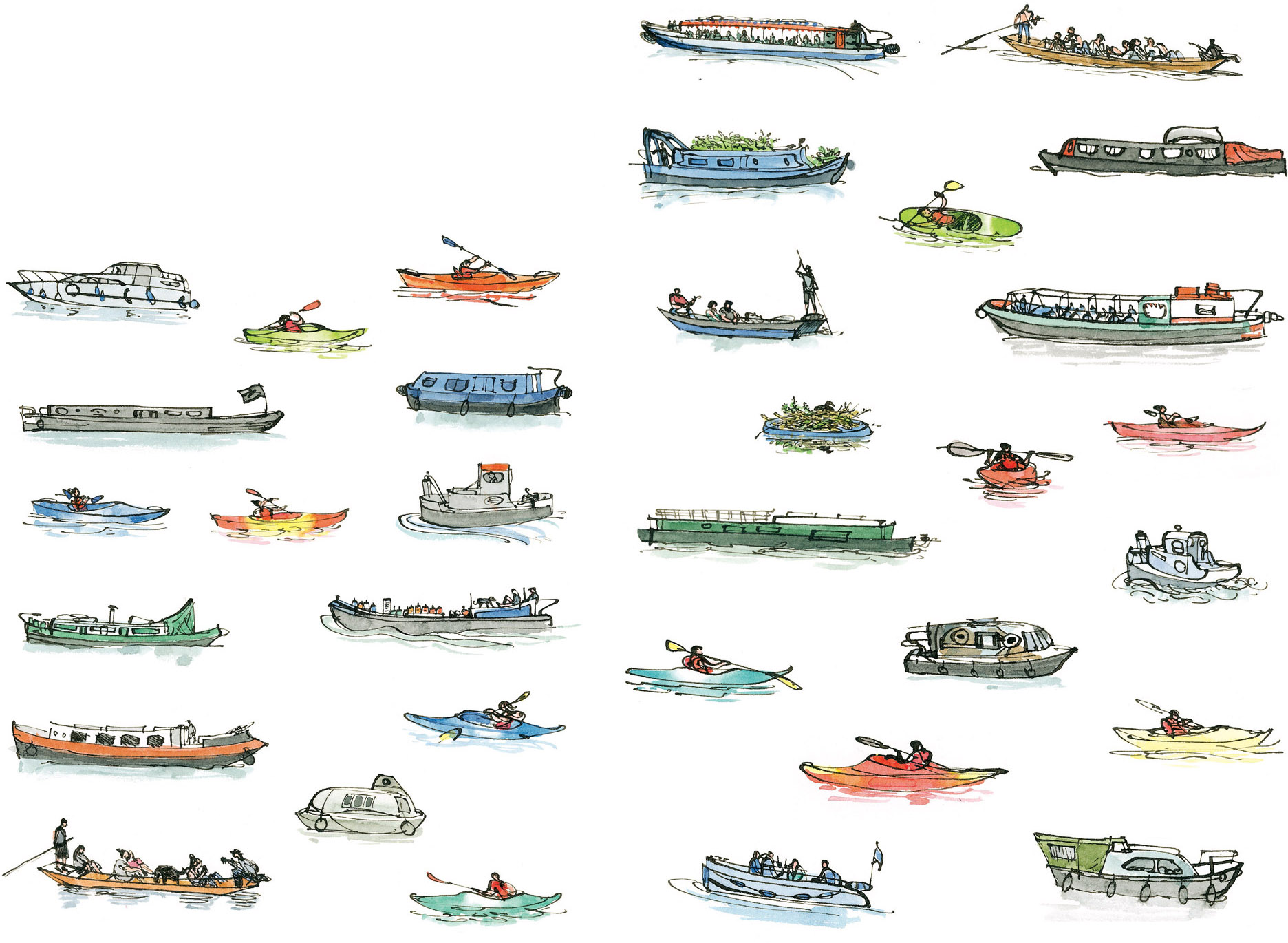

The boats on the canal are for pleasure and for work and they’re good to draw. There’s the Jenny Wren and other regular water-buses; small drive-yourself motor-launches or boats; the canal’s own maintenance craft; a punt with on-board musicians who compete with a singer with a guitar on the towpath under the railway bridge. There are kayaks and a kayaking school for children, who are adept at turning upside-down in the water and re-surfacing, and barges for living in, growing flowers on, sitting beside, and partying on the towpath.

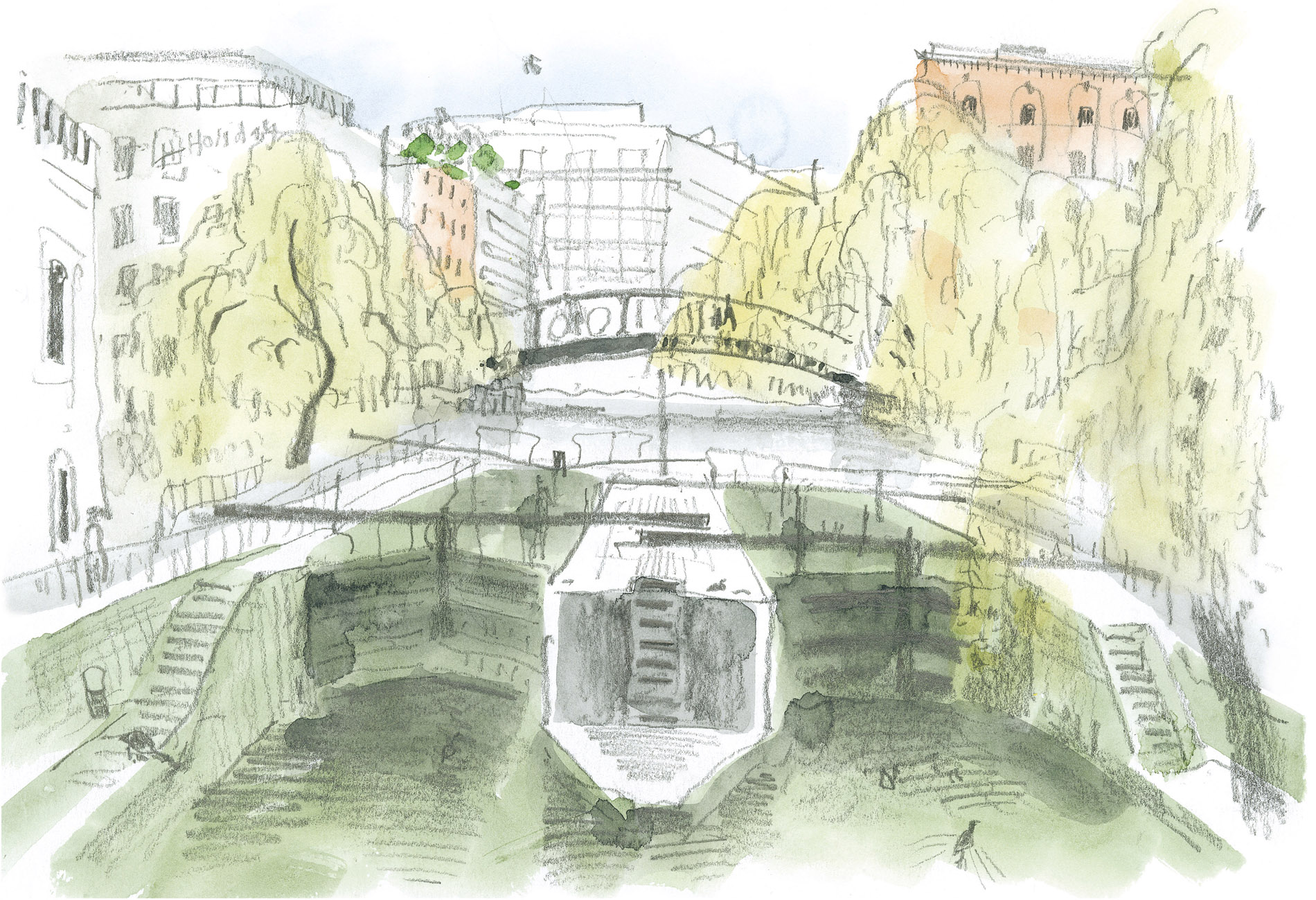

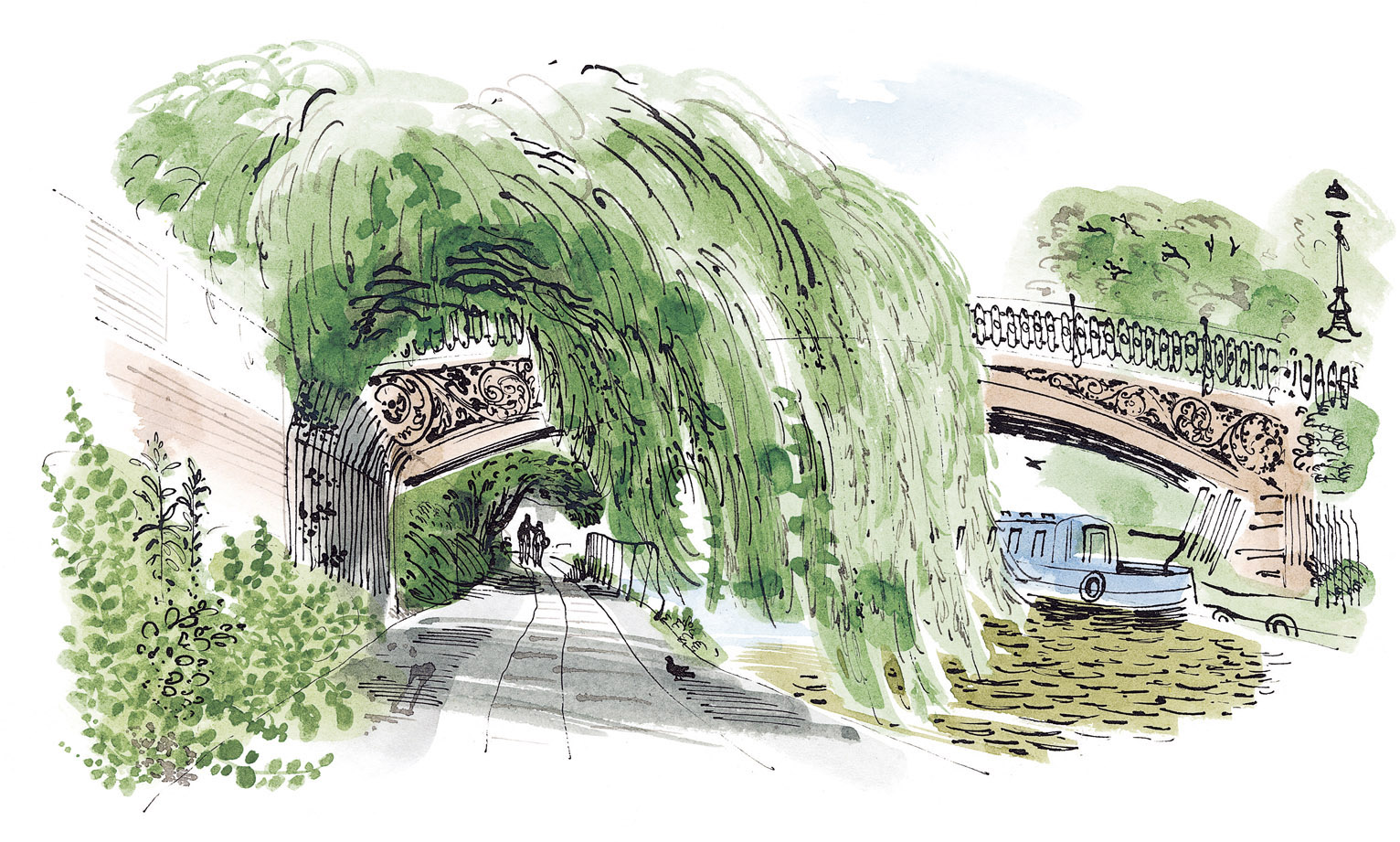

The Chalk Farm Road bridge (here) remains essentially unchanged. In summer you can’t see through the weeping willows’ foliage; in winter you hardly notice there are trees there at all. I drew this early one morning before there were many people about. Since the twin locks are symmetrical, my viewpoint was on their central axis.

The iron footbridges that cross the canal here have shallow ramps with stone setts or cobbles, designed to keep the horses from slipping as, well into the 1950s, they pulled boatloads of goods over into what’s now the Stables Market.

The narrow cast-iron roving bridge crossed the canal diagonally to make it longer and easier for the heavy carthorses to walk over. These pencil drawings were made about forty years ago as hurried studies for a watercolour. The lovely curves of the cast-iron were simpler and quicker to draw with a soft pencil than they would have been with a pen, and the lightness or darkness of the lines was made simply by pressing lighter or harder without even thinking about it.

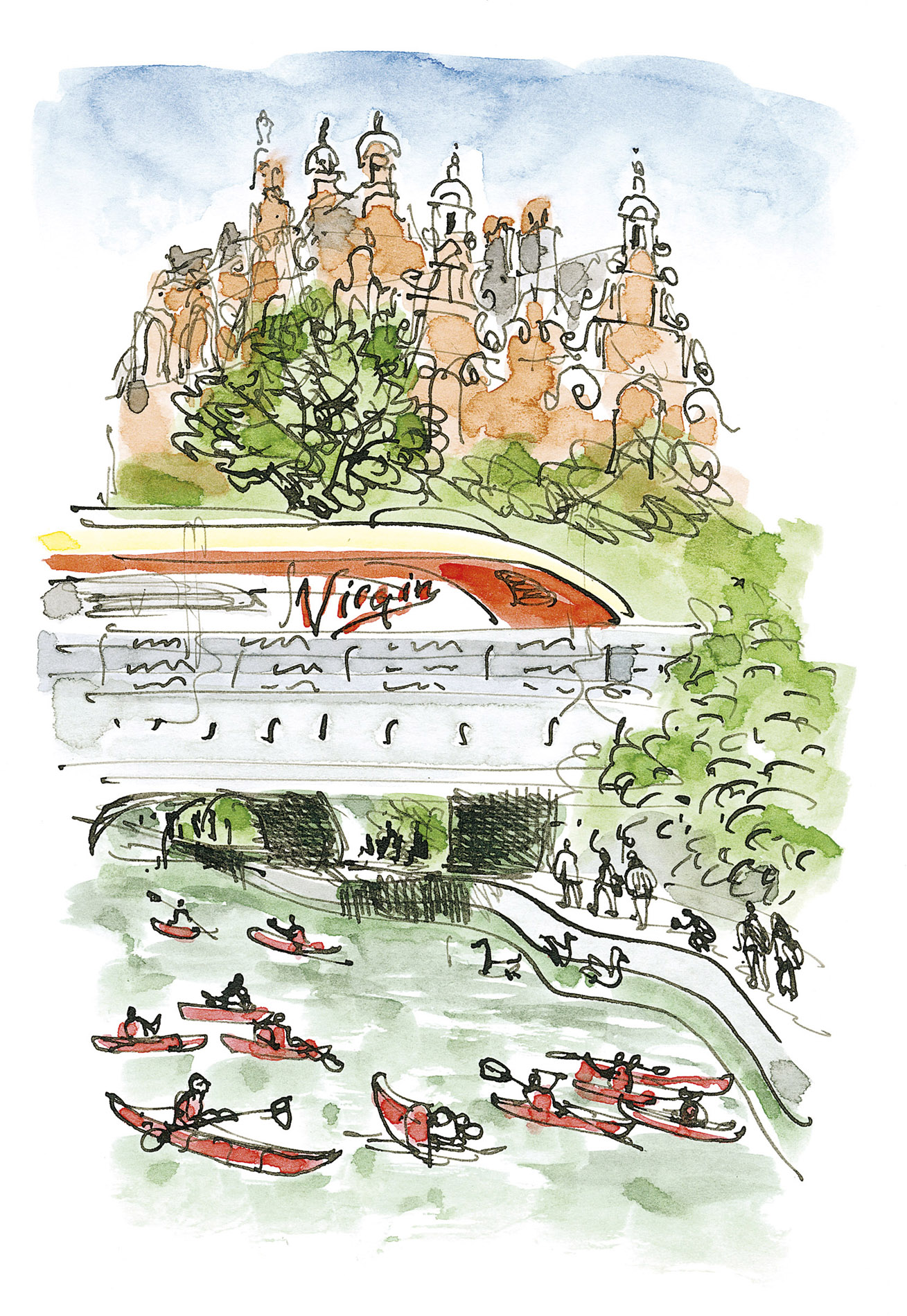

The two main features of the stretch of canal seen from the Oval Road bridge (here) are the Midland railway bridge, with its intrusively branded express trains continually passing through, and beyond it the Dutch gables of Primrose Hill Primary School.

Beside the Oval Road bridge is the Pirate Castle, a club which teaches kayaking to seemingly fearless children. Its architect – surprisingly – was Richard Seifert, who had already designed many of London’s high-rises including, in 1963, Centre Point, where Tottenham Court Road crosses Oxford Street.

The kayaks haven’t frightened away the ducks, geese, moorhens and coots which frequent the canal and bring up their young here. This sunny stretch of towpath widens out enough to attract groups of visitors resting after an exhausting tour of the market.

At the far end of the Zoo begins the wildest and leafiest stretch of the whole canal. At its centre is Macclesfield Bridge, known locally as Blow-up Bridge, temporarily destroyed in 1874 by the explosion of a barge carrying five tons of explosives. It was rebuilt two years later using the same sturdy cast-iron Doric columns. There is usually a steady flow of boats all along on the canal, but this part of it is at its best when they’re out of sight, leaving the reflections unbroken. The narrow footpath hidden beside the towpath is at its loveliest in May when the hawthorn blossom and the cow parsley are out.