Squares and Crescents

Besides the attraction of its many landmarks and inhabitants, I’ve enjoyed living and working in Camden for its abundance of squares and crescents, which offer different opportunities and challenges when I try to draw or paint them. Some are mysterious and tucked away, others are magnificent and unmissable. I like drawing the squares (even when they’re not really square at all) because they’re full of trees, peaceful, surrounded by hedges and railings, and usually free from traffic. They’re also enlivened by people exercising, playing games and looking after children.

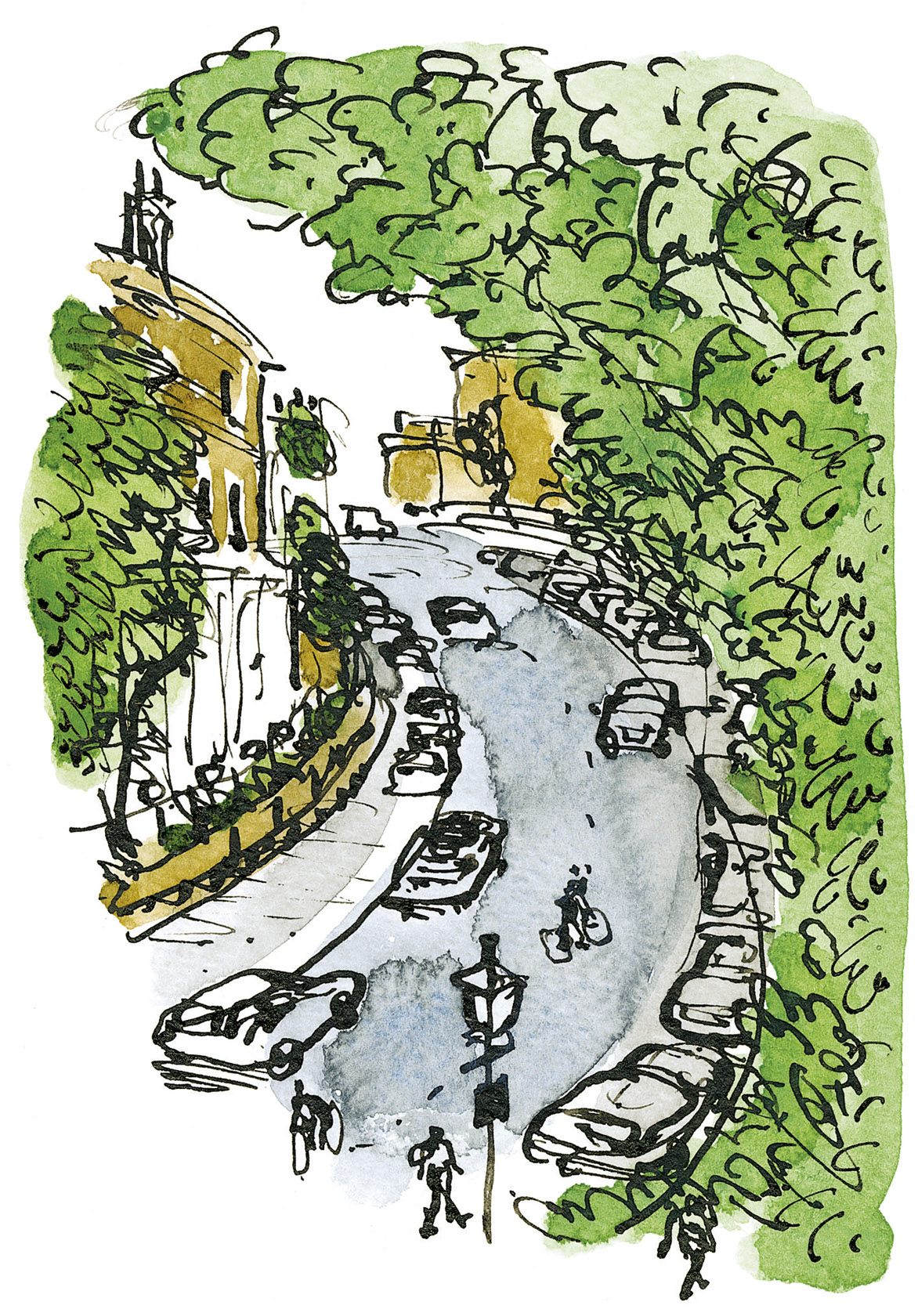

Crescents are more tantalizing because, horizontally at least, they have no straight lines. Gloucester Crescent, the oval-shaped one I’ve lived in for sixty-four years, hasn’t changed much except at its far ends. I love drawing and painting it throughout the year for the beautiful momentary or seasonal changes of light and because it’s quiet and seldom very busy, filling up with traffic only when there’s a hold-up somewhere else. I’ve drawn and painted these squares and crescents again and again because technically they’re difficult to get right, and aesthetically because they’re each individual and always beautiful. Returning to a subject is worthwhile because weather and season are always different and each time one quite literally sees it in a new light.

Old St Pancras Churchyard (here) is both beautiful and historic, with John Soane’s modest in scale but masterly mausoleum for his wife and and their son and in due course for himself too. In the 1930s the shape of its roof inspired Giles Gilbert Scott’s once familiar red telephone boxes. The most memorable presence nearby is Hardy’s Tree. The trunk of this big ash is ringed by a circle of ancient gravestones which were placed round it by Thomas Hardy as a young man while he was still an architect. Because the churchyard was quiet and relatively remote, it was the haunt of Dickens’ bodysnatchers in A Tale of Two Cities. Even now, still quiet and peaceful, it’s said to be London’s most undisturbed venue for drug-dealing.

Chalcot Square is a square that really is square, and makes a pretty and leafy playground for the children of the surrounding houses. Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath would have seen this view every time they stepped out of their front door.

Quick, slight drawings originally intended only as rough sketches may have an unexpected lightness of touch or they may be rubbish. But more careful or deliberate ones might just be earnestly boring. I can’t always tell, and asking other people simply adds uncertainty. Both ways have their virtues and drawbacks, and both need the other. In any case, time tells – it’s easier to be objective about something you drew ages ago.

Gloucester Crescent’s most striking feature is a long, curving and symmetrical stretch of terrace with a central classical pediment and two ornamental towers at each end. Drawing it is further complicated by its being built on a slope, so each individual house is slightly notched up or down from the next. Its ground floor and the pavement in front are also usually hidden by parked cars, so the precise relation of each house’s facade to the next has to be checked.

Chalcot Crescent must have been planned to fit as many dwellings as possible into a limited space. It’s the only S-shaped crescent I know, swirling first to left and then to right. The curves are complicated, beautiful and intriguing. It’s difficult to draw them accurately, but drawings needn’t always be accurate: I’ve removed the parked cars, which in reality only happens when the place is being re-tarmacked or filmed. Balcony railings, glazing bars, street railings, pavement kerbs and parking lines all follow and emphasize the sinuous curves.