George Hudson, Capitalist Hero

In the early 1950s a Swarthmore College social psychologist named Solomon Asch performed a series of seminal experiments that make sense of the infectiousness of the medieval apocalyptic mass delusions and eighteenth-century financial manias.

Asch seated groups of about a half dozen male participants around an oblong table and told them that they were being tested for visual perception. All in the room were shown a card with a line of fixed length, say 3¾ inches. They were then shown a second card with three lines, one of which was the same 3¾-inch length, and the other two of slightly different lengths, say 3 and 4¼ inches. The participants were asked to pick the line that matched that on the first card. This task required some concentration but was easy enough that normal subjects made errors on each card pair about 1 percent of the time, and got all of a series of twelve card pairs correct 95 percent of the time.

Many, if not most, psychology experiments require fibbing to their subjects. This test wasn’t about visual perception at all, and each group contained only one actual subject. The other participants were in fact Dr. Asch’s assistants; the subject sat near the middle of the table, so as to minimize his average distance from the ringers.

The subject tested either last or next to last and was thus exposed to multiple responses from Asch’s collaborators before answering. When the ringers answered correctly, the subjects performed similarly to those tested alone, getting all twelve card pairs correct 95 percent of the time. But when the ringers deliberately answered incorrectly, the actual subjects’ performances plummeted. Only 25 percent of them scored all twelve pairings correctly, and incredibly, 5 percent answered all twelve incorrectly.226 Further, subjects performed consistently from trial to trial: Those who were highly influenced by the ringers’ errors in the first six pairings were similarly influenced in the last six. That is to say, some of the subjects were reliably more suggestible than others.

Card used in Asch Experiment.

Asch interviewed the subjects following the study, and their responses were revealing. The suggestible ones worried that their eyesight or mental processing were failing them; one commented, “I know the group can’t be wrong.”227 Even the nonsuggestible ones were disturbed by their disagreement with the majority and sensed they were right, and few of these were completely sure.

Striking social science experiments often produce a fair amount of subsequent urban myth, and such was the case with Asch’s results. In the decades following his research, its conclusions have been increasingly represented in the popular press, in textbooks, and even in the academic literature as suggesting that most people are strongly conformist.228

The data presented, however, a more nuanced picture. More than half of the subjects’ responses in the presence of the confounding ringers were correct—that is, nonconformist. Further, the presence of even a single ringer who responded correctly significantly decreased the error rate of the subjects. A more accurate summary of the Asch experiment is that some people are more suggestible than others, and that many—25 percent of the subjects—are not at all suggestible. It is easy, though, to imagine that Asch would have identified those most susceptible to a financial bubble or to an apocalyptic creed.

Asch’s results are especially striking, since few tasks are more emotionally neutral than estimating line length. So is yawning, a subject about which people tend not to have an emotionally driven opinion. Yet, as most of us know, and has been experimentally proven, yawning is infectious. Infectious yawning can be induced in normal, fully awake subjects not only by other people’s yawns, but also by mere videos of yawning people, even those whose mouths have been obscured. Curiously, videos showing only the mouth fail to induce yawning.229

In emotionally laden situations, conformism rises. Charles Kindleberger’s admonition about the detrimental effects of watching someone else get rich applies to Asch’s findings about how some subjects were more suggestible than others; someone who successfully resists social pressure in the lab is less likely to resist an emotionally laden mass delusion.

Imitation is not just the sincerest form of flattery; it’s also essential to our survival. Over the course of human evolution, our species has had to adapt to a wide variety of environments. That adaptation has taken two forms. The first is physical. To take an obvious case, Africans have darker skin than northern Europeans; darker skin protects the underlying tissues from damaging tropical sunlight, and, conversely, lighter skin allows for more efficient vitamin D production in less sunny northern latitudes.

The other adaptations are cultural and psychological. As pointed out by pioneering evolutionary psychologists Robert Boyd and Peter Richerson, the skill sets required for survival in the Amazon rainforest are very different from those required of people who live in the Arctic, who

have to know how to make dozens of essential tools—kayaks, warm clothing, toggle harpoons, oil lamps, shelters built of skin and snow, goggles to prevent snow blindness, dog sleds and the tools to make these tools. . . . While we are rather clever animals, we cannot do this because we are not close to clever enough. A kayak is a highly complex object with many different attributes. Designing a good one means finding one of the extremely rare combinations of attributes that produces a useful boat.230

In other words, making a kayak from the locally available raw materials if you’ve never seen it done before is nearly impossible. The same is true of the very different skill set needed by an Amazon native. Humans needed less than ten thousand years to migrate from the Bering Strait to the Amazon, which means that we must have previously evolved the tendency to imitate accurately. In the words of Boyd and Richerson, being able to survive in such different surroundings means that humans have had to

evolve (culturally) adaptations to local environments—kayaks in the Arctic and blowguns in the Amazon—an ability that was a masterful adaptation to the chaotic, rapidly changing world of the Pleistocene epoch. However, the same psychological mechanisms that create this benefit necessarily come with a built-in cost. To get the benefits of social learning, humans have to be credulous. . . . We get wondrous adaptations like kayaks and blowguns on the cheap. The trouble is that a greed for such easy adaptive traditions easily leads to perpetuating maladaptions that somehow arise.231

Over the past fifty thousand or so years, the human race has spread from its home in Africa to virtually every corner of the planet, from the arctic shores to the tropics to isolated islands in the middle of the vast Pacific Ocean. Our ability to adapt to such diverse environments during our species’ late Pleistocene migration from the high Arctic to the Strait of Magellan rested on accurate imitation. Alas, many of our Stone Age adaptations have proved maladaptive in the modern world, the classic example being our ancient attraction to energy-rich fats and sugars, both scarce and life-giving in our evolutionary past but now dangerously available as cheap junk food. In the same way, our ancient proclivity to imitate is also now often maladaptive, carrying with it the modern propensity, in Mackay’s famous words, to “extraordinary mass delusions and the madness of crowds.”

The spread of mass delusions also feeds on another ancient psychological impulse, our propensity to suppress facts and data that contradict our everyday beliefs. In 1946, psychologist Fritz Heider posited the so-called “balanced state” paradigm to explain how people deal with the large amount of complex and often contradictory data presented to us in the course of daily life. Imagine that you know someone named Bob and that both you and he have an opinion about something that carries a modest amount of emotional freight, such as whether the Android phone or the iPhone is a superior mobile device.

If you admire Bob, and you both think the iPhone is better, then you’re comfortable; you now occupy Heider’s balanced state. Similarly, if you think the iPhone is better, but Bob loves his Android phone, and you think that he’s an ignorant jerk, you’re also in a balanced state, since your negative opinion of Bob allows you to dismiss his contrary opinion.232 But if you admire Bob and disagree about phones, you’re now in an uncomfortable “unbalanced state.”

If you only modestly admire Bob, or if you really don’t care that much about phones, you can easily ignore your discomfort. But if Bob is your dearest friend and you disagree strongly about something that carries more emotional weight, such as the Trump presidency, you’re going to have to act to address the imbalance between your admiration of Bob and your political disagreement. Neuroscientists have recently found that such unbalanced states increase activity in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), brain areas in both hemispheres just above the top of the middle of your forehead. Further, this activity predicts a change in opinion, either about Bob or about Donald Trump. In other words, if you want your dmPFC to stop bugging you, you’ll have to change your opinion about one or the other.233 Conversely, when a subject learns that experts agree with his or her opinion, that is, has achieved a balanced state, another part of the brain, the ventral striatum, paired structures located deeply in both hemispheres, fires intensely.234 This area receives its densest inputs from neurons responding to dopamine, our pleasure-providing neurotransmitter of choice.

In the original 1841 edition of Extraordinary Popular Delusions, Mackay wrote of the South Sea Bubble,

Enterprise, like Icarus, had soared too high, and melted the wax of her wings; like Icarus, she had fallen into the sea, and learned, while floundering in its waves, that her proper element was the solid ground. She has never since attempted so high a flight.235

Yet within a few years of writing those words, the financial markets would prove Mackay wrong, for the Icarus of speculation soared again with a financial mania that would dwarf the 1719–1720 South Sea Bubble, this time surrounding the excitement and dislocation wrought by the first steam railways. Few writers captured the pre-steam human condition better than historian Stephen Ambrose:

A critical fact in the world of 1801 was that nothing moved faster than the speed of a horse. No human being, no manufactured item, no bushel of wheat, no side of beef, no letter, no information, no idea, order or instruction of any kind moved faster. Nothing had ever moved any faster, and, as far as Jefferson’s contemporaries were able to tell, nothing ever would.236

In 1851, English historian John Francis wrote the classic eyewitness account of the building of the nation’s railway network. He described the state of premodern transport as follows:

The machines which were employed to convey produce, rude and rough in their construction, were as heavy as they were clumsy. Even if the roads were tolerable, it was difficult to move [those machines], but if bad, they were either swallowed in bogs, or fell into dykes: sometimes, indeed, they sunk into the miry road so deep, that there was little chance of escape until the warm weather and the hot sun made their release easy. Markets were inaccessible for months together, and the fruits of the earth rotted in one place while a few miles off the supply fell far short of demand. . . . It was found cheaper to export abroad than to convey produce from the north to the south of England. It was easier to send merchandise from the capital to Portugal, than to convey it from Norwich to London.237

The idea of using steam power to perform physical work, previously the province of men, beasts, and water mills, goes back two millennia to the Ptolemaic Greeks, who supposedly used it to open and close the doors of a temple in Alexandria. An English inventor, Thomas Newcomen, produced the first working steam engine around 1712, which was so massive and inefficient that it could be used only to drain coal mines, where its fuel was plentiful. James Watt thus didn’t invent the steam engine in 1776, as is commonly supposed, but accomplished something more subtle and effective: by adding an external condenser to the Newcomen design, he produced a device fuel-efficient enough to be used far from a coal mine. This innovation allowed Watt’s partner, Matthew Boulton, to famously say, “I sell here, sir, what all the world desires to have—Power.”238

Over the next quarter century, Watt’s bulky engines first drove boat paddles, then slimmed down enough for Richard Trevithick to mount one on a land carriage in 1801; by 1808, he was offering five-shilling rides near London’s Euston Square. The early devices, made of soft iron, were so weak that one early engineer’s wife, besides having to awaken at 4 a.m. to stoke the engine, also had to apply her strong shoulder to get it moving.239

At the turn of the eighteenth century, George Stephenson, the son of an illiterate Northumberland steam engine tender, acquired his father’s trade, but unlike him also acquired reading, writing, and math skills in night school, and he applied his genius toward gradually improving the output of the early steam devices. In the immediate aftermath of the costly Napoleonic Wars, the high price of hay temporarily allowed steam to nudge out horse-drawn coal mine wagons, but not until 1818 did Stephenson convince mine owners at Darlington, near Newcastle, to build a marginal, but ultimately economically successful, steam rail line to the wharves at Stockton-on-Tees, twenty-five miles away, which opened in September 1825.240

The new rail technology transfixed the world: between 1825 and 1845, England experienced no fewer than three railway bubbles. The first followed on the heels of the Stockton and Darlington line. Stephenson’s early engines were so unreliable that during their first years of operation the line’s coal and passenger cars more often than not had to be pulled by horse. As the engines improved, as many as fifty-nine more rail lines were planned.241

The first projects met with no small opposition in Parliament, which, because of the Bubble Act, the now century-old relic of the South Sea episode, had to approve all incorporations. The canal and turnpike operators, who correctly perceived the damage rail transport would do their profits, were particularly active opponents. They and their minions told the public that engine smoke would kill the birds; that the weight of the engines would render them immobile; that their sparks would incinerate goods; that the elderly would be run over; that frightened horses would injure riders; that horses would become extinct and so bankrupt oat- and hay-growing farmers; that foxes would disappear; and that cows, disturbed by the noise, would cease to yield milk.242

In 1825, Parliament repealed the Bubble Act, but a generalized financial panic, combined with the primitive engine technology, put a damper on further projects. After a turbulent parliamentary passage in 1825–1826, Stephenson’s Liverpool and Manchester Railway took four years to complete, formally opening on September 15, 1830. Thirty-five miles long, it was the engineering marvel of its age, requiring the construction of sixty-four bridges and the excavation of three million cubic yards of earth.

This remarkable new technology, which promised to transform everyday life, stoked the greed of those wishing to get in on its ground floor. The excitement peaked in 1836–1837. Wrote a journalist, “Our very language begins to be affected by [the railroads]. Men talk of ‘getting up the steam,’ of ‘railway speed,’ and reckon distances in hours and minutes.”243 One press report mentioned a merchant who traveled from Manchester to Liverpool, returned the same morning with 150 tons of cotton, sold it at great profit, and then repeated the feat. “It is not the promoters, but the opponents of railways, who are the madmen. If it is a mania, it is a mania which is like the air we breathe.”244 John Francis wrote, “The memory of those months which range from 1836 to 1837 will long be remembered by commercial men. Companies that engrossed the care and the capital of thousands, were projected.”245

The allure of the hypnotic new technology was amplified, as is almost always the case with bubbles, by falling interest rates, which made investment capital more plentiful. A quarter century before, the borrowing needs necessitated by the Napoleonic Wars had raised interest rates; at their height in 1815 a wealthy Englishman could buy government bonds yielding nearly 6 percent in gold sovereigns. Over the following three decades rates fell to 3.25 percent.246 When investors are unhappy with ultra-low interest rates offered on safe assets, they bid up the prices of risky assets with rosier potential income. Writing a generation after the English railway bubbles had burst, the great journalist (and founder of The Economist) Walter Bagehot wrote, “John Bull can stand many things, but he cannot stand two percent.”247 In other words, low interest rates are the fertile ground in which bubbles sprout.

The low interest rates, together with the success of the period’s first mover, Stephenson’s Liverpool and Manchester Railway, reignited railway speculation: “The press supported the mania; the government sanctioned it; the people paid for it. Railways were at once a fashion and a frenzy. England was mapped out for iron roads.”248

Every bubble carries within it the seeds of its own destruction, in this case the excessive competition wrought by duplicate railway lines fed by cheap capital. The Liverpool and Manchester shareholders got the steak, while those who followed more often than not fed on more rancid fare. Noted the Edinburgh Review in 1836, “There is scarcely, in fact, a practicable line between two considerable places, however remote, that has not been occupied by a company. Frequently two, three, or four rival lines have started simultaneously.” John Francis wrote that “in one parish of a metropolitan borough, sixteen schemes were afloat, and upward of one thousand two hundred houses scheduled to be taken down.”249

These were merely the most credible of the schemes. In Durham, one entrepreneur began work on three parallel lines. The first was successful, and the other two, naturally enough, failed. Other promoters envisioned engines variously propelled by sails or rockets, the latter traveling at hundreds of miles per hour; elevated wooden rail lines; and another advertised, according to Francis, “to carry invalids to bed.”250

Everywhere and always, freely available credit and credulous investors are catnip to the rogue promoter. One contemporary observer noted that, typically,

A needy adventurer takes it into his head that a line of railway from the town A to the town B is a matter of great public utility, because out of it he may get great public benefit. He therefore procures an Ordnance map, Brooke’s, or some other Gazetteer, and a Directory. On the first he sketches a line between the two towns, prettily curving here and there between the shaded hills for the purpose of giving it an air of truth, and this he calls a survey, though neither he nor any one for him had ever been over a single foot of the country. The Gazetteer, Directory, and a pot of beer to a cad or coachman, supply him with all the materials for his revenue, which fortunately never fails to be less than 15, 20, or 30 per cent. per annum, and is frequently so great that his modesty will not allow him to tell the whole.251

As supposedly said by Edmond de Rothschild, “There are three principal ways to lose money: wine, women, and engineers. While the first two are more pleasant, the third is by far the more certain.”252 As more lines entered construction, the pool of available competent engineers and laborers shrunk, leading to delays, massive cost overruns, and dubious solutions to engineering difficulties, ending in the inevitable rash of bankruptcies.

As already seen during the South Sea Bubble, English joint-stock companies initially raised only a small percent of the needed capital. Investors, who had initially put up only a fraction of the face value of their shares, were liable for further calls of the capital needed for ongoing railroad construction—a “leveraged” structure of dry tinder that inevitably met its match.

The time of reaction was at hand. Money became scarce; the eyes of the people were open to their folly; and shares of every description fell. Then came that terrible revulsion, when ruin visits the social board, and sorrow desolates the domestic hearth. Men who had lifted their heads in the pride of presumed riches, mourned their recklessness, and women wept that which they could not prevent.253

When the smoke from the 1830s bubble cleared, Parliament had sanctioned the building of 2,285 miles of track, less than a quarter of which was actually open by 1838. The rest of the mileage, often unprofitable, took several more years to complete; the ongoing construction required substantial calls for capital from investors. Nonetheless, shares did recover in price following the 1836–1837 plunge, and those who held on to their railroad equities did not fare badly; share prices, which had been stable before 1836, spiked upward by about 80 percent in that year, then just as rapidly fell back to levels that were actually somewhat higher than pre-bubble values.254 By 1841, it was possible to travel the nearly three hundred miles from London to Newcastle in seventeen hours: “What more can a reasonable man want?” crowed the Railway Times.255

By 1844, in fact, the average shareholder in the companies established during the previous decade was well pleased with their investment return. This paved the way for yet another, even more spectacular, bubble in the later 1840s, whose totemic figure was George Hudson. Born in 1800 the son of a small-landowning Yorkshire farmer, Hudson grew up on the reasonable assumption that he, too, would till the land, and thus received little formal education. When his father died at age nine, he was apprenticed to a linen draper in York, which proved a blessing in disguise. Hudson’s energy, charm, and intelligence soon became apparent on the shop floor in a way that they would not have behind the plow, and he eventually married into his employer’s family and took over the business. Fortune continued to smile on the young proprietor when, in 1827, he inherited £30,000 from a great uncle whose decline he had attended (and whose will had been suspiciously changed in Hudson’s favor at the last moment).256

His newfound wealth allowed him entrée into politics and banking, which led, in 1833, to his nomination as treasurer of the York Railway Committee, charged with establishing a local line funded by a stock floatation. Hudson hired Sir John Rennie to survey the route, but the noted engineer disappointed the committee by recommending a horse-drawn system. Fortuitously, while visiting some property left to him by his great uncle, he met George Stephenson; subjected to the full glare of Hudson’s charisma and vision, the now legendary engineer agreed to build the York and North Midland Railway, funded as a joint-stock company, whose first segment, just 14.5 miles long, opened in 1839.

Over the next decade, the “Railway King,” as Hudson became known, created an empire of a dozen or so railway companies, including four of the nation’s largest. He directed several corporate boards, here surveying a new line, there directing anger at the shareholder meeting of a failing one, and everywhere raising new capital. His life revolved around two centers of power: York, where he served several terms as a generous and well-loved mayor, and the nation’s political center at Westminster.

Hudson could sell sand to a Bedouin. Able to turn even his most determined opponents, his signature victory was over William Ewart Gladstone. Perhaps the most formidable politician of the nineteenth century, Gladstone entered Parliament in 1832 at age twenty-two. Critically, in 1843 he became president of the Board of Trade, which functioned as the parliamentary gateway for railway legislation. He went on to serve four spells as chancellor of the exchequer and also four terms as prime minister between 1868 and 1894.

The two men could hardly have been more different: Hudson the boisterous, uneducated issue of Yorkshire peasant stock; Gladstone, the Eton- and Oxford-groomed heir of slaveholding wealth. They also differed on the most critical issues of the day; Hudson was an orthodox Tory opponent of repeal of the protectionist corn laws; Gladstone, while nominally a Tory, was a passionate free-trader.

Hudson would today be called a libertarian, opposed to any government interference with commerce, particularly with his cherished railways, while Gladstone early on saw the need for government regulation in an increasingly technologically advanced economy. Several decades before the cost-cutting predations of John D. Rockefeller, Gladstone also foresaw that the strongest railroads could drive their competitors out of business with aggressive fare reductions and thus leave the public at the mercy of the surviving railway monopoly—increasingly, it appeared to Gladstone, one run by Hudson.

In March 1844, testifying before the Board of Trade, Hudson deftly emphasized his points of agreement with Gladstone: it would well serve the public interest (to say nothing of his own) to limit the approval of further competing lines. The committee pushed back by closely questioning Hudson on precisely how he set his fares. What, the committee wanted to know, was wrong with Parliament periodically revising fares? Hudson was, as always, well prepared, answering that he would have no objection to allowing government-mandated fares in exchange for parliamentary limitation of charters for competing lines.

Somewhat placated by Hudson’s answer, the committee proposed relatively mild railway legislation that mandated a “Parliamentary Class” fare of a penny per mile.257 The bill allowed Parliament to revise the fares of companies that were so profitable that they could issue dividends in excess of 10 percent, and for the government to purchase any railway chartered after the bill’s passage and after it had been operating for more than two decades.

This was too onerous for Hudson, who threw his legions into action and wrote a public letter to Gladstone, which, in the sweetest and most flattering tone, laid out his objections to the bill’s provisions for fare reductions and option for government purchase. He arranged a deputation of railway owners to 10 Downing Street, and so impressed the prime minister, Robert Peel, that he made favorable comments about the railway companies on the floor of Commons.

Gladstone took the hint and met privately with Hudson, who turned his bluff Yorkshire charm up so high that the committee chair was later moved to observe, “It is a great mistake to look upon [Hudson] as a speculator. He was a man of great discrimination, possessing a great deal of courage and rich enterprise—a very bold, and not at all unwise, projector.” Hudson so impressed Gladstone that he gutted the bill; of its original provisions, only the low fixed third-class fare remained.258

Hudson’s close call with potential parliamentary oversight impressed upon him the need for more vigorous political involvement. While today a powerful industrialist might hire an army of lobbyists, the more relaxed ethical environment in nineteenth century Britain allowed for a more direct route: Hudson would simply buy himself a seat in Commons. In mid-1845, the opportunity arose. In exchange for taking over a failing local railway and wharf, the town fathers of sleepy coastal Sunderland nominated him as the Tory candidate for its seat, to which he was duly elected on August 14. The closest modern equivalent would be the chairman of Goldman Sachs simultaneously serving in the U.S. Senate.

That evening, a special train carried the news of his election from Sunderland to London, and the next day another train carried copies of the London morning papers’ account of the event back to Sunderland, where, at a riotous victory celebration, Hudson flung the papers into the crowd, crowing, “See, see the march of intellect!”259 Two months later, at a banquet in Sunderland, he again roused the locals by floating shares in his dock company: “I do not see why you should not have cotton from St. Petersburg, and the produce of China and other parts of the world come to the port of Sunderland, provided you offer the facilities . . . let us imagine we are going to be the Liverpool and Manchester of the world.”260

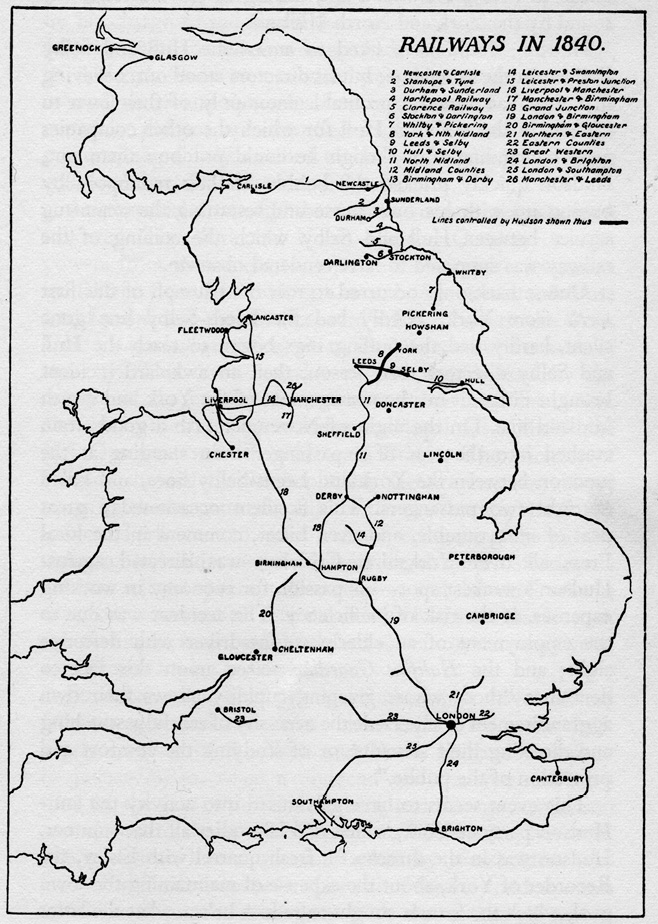

British Railway System in1840 (Hudson’s lines in bold). Source: The Railway King, by Richard S. Lambert, London, George Allen & Unwin Ltd, © 1964, p. 57. Copyright ©1934 HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.

British Railway System in1849 (Hudson’s lines in bold). Source: The Railway King, by Richard S. Lambert, London, George Allen & Unwin Ltd, © 1964, p. 238. Copyright ©1934 HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.

He seemed barely to sleep; on the night May 2–3, 1846, for example, he worked in the House of Commons until 2:30 a.m., dozed briefly, then caught the early train to Derby, roughly halfway between London and York and the headquarters of the Midland Railway, one of his companies. There he explained to gobsmacked shareholders the essence of his twenty-six parliamentary bills that amalgamated rail and canal systems, built new ones, and extended others. This scheme required £٣ million of investor capital; he freely admitted to the skeptical that many of the new lines would fail, but that in the aggregate they would forge an unassailable regional rail system. Already in possession of a raft of favorable proxies, he easily brushed aside scattered opposition from dissident shareholders to pass all twenty-six of his corporate proposals.261 Wrote one contemporary observer,

Nothing seemed to wear his mind; nothing appeared to weary his frame. He battled in parliamentary committees, day by day; he argued, pleaded, and gesticulated with an earnestness which rarely failed in its object. One day in town cajoling a committee—the next persuading an archbishop. In the morning adjusting some rival claim in an obscure office; in the afternoon astonishing the stock exchange with some daring coup de main.262

His powers of concentration and calculation mesmerized. Frequently, he was observed to throw back his head, cover his eyes, and accurately predict the dividend of an as-yet-unfinished line, or to intensely engage in two conversations simultaneously. Business associates found themselves cut off at the knees if their analyses were not to the point, but he forgave easily, and his generosity to both employees and strangers was legendary. Unfortunately, his facility with numbers and frenetic dealings had a downside: he relied excessively on verbal orders and did not keep books or records of his massive transactions, and simply assumed that his wishes would be carried out.263

England, which had not 2,000 miles of railroads in 1843, had more than 5,000 by the end of 1848; Hudson controlled some 1,450 of those iron miles and held a virtual monopoly over the nation’s northeast.264 Far more trackage was planned: Parliament approved 800 miles in 1844, 2,700 in 1845, and 4,500 in 1846. The modus operandi of Hudson, and of most of the other promoters, involved selling shares for a small down payment and completing the full purchase much later. The new shares usually advertised dividends approaching 10 percent per annum, despite the fact that construction, let alone operations and revenues, had not yet commenced; most investors, attracted by the high yields, failed to notice that the absence of revenues implied that the earliest dividends would have to come out of new capital, which today would be labeled a Ponzi scheme, and that the later dividends were a fiction. Hudson fed the frenzy by leaking news of the parliamentary prospects of his own projects. As frosting on the cake, until the final stage of the bubble, Hudson’s dense northeastern network blocked the flotations of competing lines.

In addition to promoters like Blunt and Hudson, the public, and politicians, a fourth p in the Theater of the Bubble emerged in the 1840s: the press. Broadly speaking, in that era, the fourth estate divided itself into two groups, the “old media,” exemplified by The Times of London, and the “new media” of railway specialty reporting, such as the Railway Times; the former maintained a highly orthodox skepticism, while the latter fanned the flames of speculation. At the height of the bubble, the public could choose among at least twenty railway publications, upon which the railway company promoters lavished £12,000 to £14,000 per week in advertising revenues—funds that would have been more wisely spent on construction. Puff pieces about new proposals abounded; satirized one observer, “Its committee rejoiced in esquires and baronets. Its prospect of passing the House of Commons was certain. Its engineer was Stephenson [in this case, Robert Stephenson, George’s son]; its potentate, Hudson; its banker, Glyn. The profits, it was modestly added, would not exceed fifteen percent.”265 Gushed one typical article, the railways were a new world wonder, encircling the globe:

Not content with making Liverpool their lineage home . . . they are throwing a girdle around the globe itself. Far-off India woos them over its waters, and China listens to the voice of the charmer. The ruined hills and broken altars of old Greece will soon re-echo the whistle of the locomotive, or be converted to shrines sacred to commerce, by the power of those magnificent agencies by which rivers are spanned, territories traversed, commerce enfranchised, confederacies consolidated; by which the adamantine is made divisible, and man assumes a lordship over time and space.266

As late as 1843, the British economy was still recovering from the indigestion of 1836–1837, but in the fall of 1844, banks were loaning at 2.5 percent; even more ominously, they were happy to accept as collateral railway securities, widely considered “safe as houses.” The subscription rolls saw entries that would make an early 2000s American mortgage broker blush: a half-pay military officer earning £54 per year down for a total of £41,500 on multiple lists; two charwoman’s sons living in a garret, one down for £12,500 and the other for £25,000, almost all of which consisted of calls that they had no hope of meeting; millions more pounds sterling of calls came from shareholders with fictitious addresses.267

According to one anonymous observer, the English public,

saw the whole world railway mad. The iron road was extolled at public meetings; it was the object of public worship; it was talked of on the exchange; legislated for in the senate; satirized on the stage. It penetrated every class; it permeated every household; and all yielded to the temptation. Men who went to church as devoutly as to their counting houses—men whose word had ever been as good as their bond—joined in the pursuit, and were carried away by the vortex.268

Observed the businessman and MP James Morrison,

The subtle poison of avarice diffused itself through every class. It infected alike the courtly and exclusive occupant of the halls of the great and the homely inmate of the humble cottage. Duchesses were even known to soil their fingers with scrip, and old maids to inquire with trembling eagerness the price of stocks. Young ladies deserted the marriage list and the obituary for the share list, and startled their lovers with questions respecting the operations of bulls and bears. The man of fashion was seen more frequently at his broker’s than at his club. The man of trade left his business to look after his shares; and in return, both his shares and his business left him.269

Parliament’s Board of Trade established an annual deadline of November 30, by which date plans for new lines had to be filed. On the evening of the 1845 deadline, a frenzy engulfed the capital as promoters representing eight hundred schemes converged on the Board’s Whitehall offices: special express trains that the lines allowed through sped toward London at speeds of eighty miles per hour. Railway companies blocked the trains carrying proposals from competing lines; one projector got around this hurdle by loading onto a train a fully decked-out hearse containing proposal documents.270

John Francis wrote that, as during the South Sea Bubble, ’Change Alley clogged with crowds and gridlock and was once again described as “almost impassable,” and the surrounding neighborhoods were “like fairs.” He continued,

The cautious merchant and the keen manufacturer were equally unable to resist the speculation. It spread among them like a leprosy. It ruined alike the innocent and the guilty. It periled many a humble home; it agitated many a princely dwelling. Men hastened to be rich, and were ruined. They bought largely; they subscribed eagerly; they forsook their counting-houses for companies; if successful they continued in their course, and if the reverse, they too often added to the misery of the homes they had already desolated, by destroying themselves.271

Stephenson’s offices on Great George Street in Westminster were more sought-after than the prime minister’s on Downing Street; the price of iron doubled, and surveyors, particularly those working for the Ordnance Department, who often illegally entered private land without permission, could and did charge the earth. A parliamentary report yielded 157 MPs with share subscriptions in excess of £2,000; by the summer of 1845, “The neglect of all business has been unprecedented; for many months no tradesman has been found at his counter, or merchant at his office, east, west, south, or north. If you called upon business you were sure to be answered with ‘Gone to the city.’” Even the Brontës got into the act: Emily and Anne owned York and North Midland shares, while the apparently better-grounded Charlotte was more skeptical.272

While many of Hudson’s business practices, particularly his secrecy and high-handed approach to corporate governance, might have landed him in jail today, they were not yet illegal. Not for another eight decades would Charles Ponzi lend his name to operations that paid dividends out of fresh capital; in the early 1840s, such practices did not arouse legal scrutiny (though that would soon change). The end came not from fraud or deceit, but rather from simple overbuilding and regulatory reform.

Unlike the twin bubbles of the previous century, the collapse of the railway companies evolved in slow motion. By the late 1840s, Hudson’s system, which stretched roughly from London almost to Edinburgh, found itself ever more hemmed in by competing lines to both the east and the west. In a desperate attempt to outflank the competition with further line extensions, he raised vast amounts of capital from individual investors; simultaneously, Parliament established a new regulatory regime in 1847 that finally did outlaw the Ponzi-like payment of dividends out of newly acquired capital.273

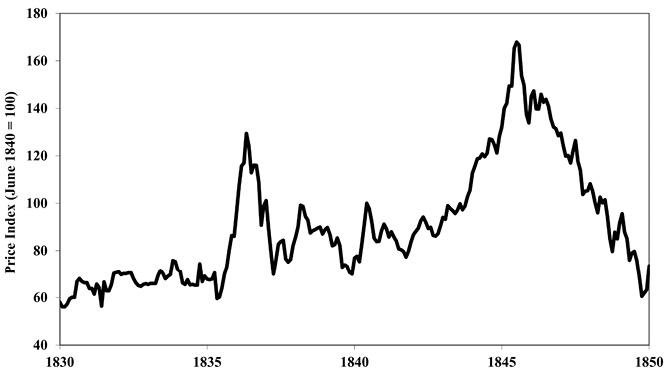

The Bank of England administered the coup de grâce in early 1847 when it raised the discount rate from 3.5 percent to 5 percent. This choked off the flow of capital needed to meet the calls required by share subscriptions. The failure of the potato crop in 1846 and the Continent-wide revolutionary disturbances of 1848 added to England’s economic woes and forced Hudson and the other railway operators to cut dividends: panicked investors sold off, and by October 1848 share prices had fallen by 60 percent from their peak 1845 value.274

Figure 4-1. British Railway Share Prices 1830–1850

While the absolute share-price decline was not as great as those seen during the South Sea Bubble, or even during the great twentieth-century bear markets, the extreme degree of leverage inherent in the subscription purchase mechanism resulted in widespread devastation:

Entire families were ruined. There was scarcely an important town in England but what beheld some wretched suicide. Daughters delicately nurtured went out to seek their bread. Sons were recalled from academies, households were separated: homes were desecrated by emissaries of the law. There was disruption of every social tie. . . . Men who had lived comfortably and independently found themselves suddenly responsible for sums they had no means of paying. In some cases they yielded their all, and began anew; in others they left the country for the Continent, laughed at their creditors, and defied pursuit. One gentleman was served with four hundred writs. A peer similarly pressed, when offered to be relieved of all liabilities for £15,000, betook himself to his yacht, and forgot in the beauties of the Mediterranean the difficulties that had surrounded him.275

By that point, minor indiscretions that might have been earlier forgiven of the great Hudson attracted greater scrutiny. Two rival members of the stock exchange, upon close examination of purchase and sales records, noticed that one of the Railway King’s companies had bought shares of another that just happened to be owned by Hudson personally at higher-than-market prices; in other words, he had been caught red-handed bilking his own shareholders. Other, more serious infractions were soon uncovered that, while still not rising to the level of criminal liability, left him exposed to crippling civil judgments.

Hudson had one last ace up his sleeve: the gratitude of his Sunderland constituents kept him in Parliament for another decade, and as long as the House of Commons was in session, he was immune from arrest for debt. There followed an opéra bouffe sequence of sorties to and from the Continent. When Parliament was active, he could safely reside at home, where he desperately tried to salvage his holdings; upon adjournment, he decamped to Paris. When he went down to electoral defeat in 1859, the game was up; ignored by his friends and attended to only by his creditors, his last substantial holdings were confiscated. In the end, he subsisted on an annuity purchased by admirers.276

One day in 1863, Charles Dickens, returning to Britain on the Folkestone boat, encountered a friend, Charles Manby. Observed Dickens,

Taking leave of Manby was a shabby man of whom I had some remembrance, but whom I could not get into his place in my mind. Noticing when we stood out of the harbour that he was on the brink of the pier, waving his hat in a desolate matter, I said to Manby, “Surely I know that man.” “I should think you did,” said he; “Hudson!” He is living—just living—at Paris, and Manby had brought him on. He said to Manby at parting, “I shall not have a good dinner again, till you come back.”277

Two of the three railway bubbles had ruined investors and endowed Britain with essential, if unprofitable, infrastructure. Between 1838 and 1848, its track mileage increased tenfold, and the 1848 railway map looks surprisingly like today’s; almost another century passed before mileage doubled from that year.

The unfortunate railway investors had in fact provided England with an invaluable public good—its first high-volume, high-speed transport network. Before the early nineteenth century, the per capita GDP of England grew hardly at all; thereafter, it has grown by about 2 percent per year—approximately doubling once per generation—not only in England, but in other advanced Western nations as well. This transition was caused, in no small part, by the efficiencies of steam-driven land and sea transport.278 Nor would this be the last time that ruined technology investors would provide their nation’s economies with the infrastructure necessary for their growth.

Charles Mackay published the first edition of Extraordinary Popular Delusions in 1841, just before the railway mania reached its climax. More than anyone else in England, Mackay should have recognized the boom and bust as they played out. As a journalist and popular writer, he was perfectly placed to warn about it.

He did not, acknowledging the episode only in an oblique two-sentence footnote in the book’s second edition, published in 1852.279 As a young man in the 1830s, Mackay had written for and edited at two London papers, the Sun and the Morning Chronicle; in 1844, just before the railroad bubble burst, he assumed the editorship of the Glasgow Argus, a position he held for the three years of the boom and bust. A detailed analysis of the Argus’s articles, particularly the “leaders”—main articles, frequently reprinted from other papers—shows that Mackay was, in general, modestly enthusiastic about railway development. This was likely a reflection of the laissez-faire economic tenor of the time, which centered in that period around the repeal of the protectionist corn laws that benefited the landowning aristocracy and starved the urban poor by keeping grain prices high; the railways were thus a secondary concern of Mackay’s circle.280

Under Mackay’s editorship, the paper’s leading articles did repeat the dire warnings about the bubble from The Times, but the Argus also reprinted favorable articles about the railway companies from other papers. It seems, though, that Mackay, whose name is today nearly synonymous with the word “mania,” almost completely missed the massive one he lived through. In a leading piece published in October 1845, he forthrightly stated that the enthusiasm for railway shares had little in common with the South Sea Bubble, which “was founded upon no solid, but altogether an imaginary basis.” The railway enthusiasm, he thought, had a foundation that was

broad and secure. They are a necessity of the Age. They are a property real and tangible in themselves. . . . The quiet philosopher and the active man of business can perceive that there is not a more noble, or a more advantageous employment of British capital than in these projects.281

While no evidence exists that Mackay lost money in the railway mania, the blindness of the era’s most astute observer of human financial irrationality testifies to the seductive power of financial bubbles. Even by the nineteenth century, this was old news: A century before, Isaac Newton showed how even extraordinary knowledge and intelligence failed to protect the investor from the bubble’s siren song. Newton was no financial novice; by the time of the South Sea Bubble, he had been Master of the Mint for nearly a quarter century. He had earned a generous return in South Sea shares that he had bought in 1712, which he sold at a significant profit in early 1720, but later that year lost his head and bought them back at much higher prices. This lost him around £20,000 and caused him to supposedly remark that he could calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.282

England’s railway bubble reflected a technological ferment that promised to revolutionize the very fabric of everyday life. Nearly simultaneously and a continent away, a ferment of a very different sort yielded an extraordinary American end-times mania.

226. Solomon E. Asch, “Studies of Independence and Conformity: A Minority of One Against a Unanimous Majority,” Psychological Monographs Vol. 70, No. 9 (1956): 1–70. See also Asch, Social Psychology (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1952), 450–501.

227. Asch (1956), 28.

228. See, for example, Ronald Friend et al., “A puzzling misinterpretation of the Asch ‘conformity’ study,” European Journal of Social Psychology Vol. 20 (1990): 29–44.

229. Robert R. Provine, “Yawning,” American Scientist Vol. 93, No. 6 (November/December 2005): 532–539.

230. Boyd and Richerson,: 3282.

231. Robert Boyd and Peter J. Richerson, The Origin and Evolution of Cultures (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 8–9.

232. Fritz Heider, “Attitudes and Cognitive Organization,” The Journal of Psychology Vol. 21 (1946): 107–112. A similar, more formalized model of this was developed in Charles E. Osgood and Percy H. Tannenbaum, “The Principle of Congruity and the Prediction of Attitude Change,” Psychological Review Vol. 62, No. 1 (1955), 42–55.

233. Keise Izuma and Ralph Adolphs, “Social Manipulation of Preference in the Human Brain,” Neuron Interpersonal Dynamics Vol. 78 (May 8, 2013): 563–573.

234. Daniel K. Campbell-Meiklejohn et al., “How the Opinion of Others Affects Our Valuation of Objects,” Current Biology Vol. 20, No. 13 (July 13, 2010): 1165–1170.

235. Mackay, I:137.

236. Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage (New York: Simon and Shuster, 1996), 52. This statement is not strictly true, since pigeons and the French semaphore signaling system could convey very limited amounts of information faster than a horse.

237. John Francis, A History of the English Railway (London: Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans, 1851), I:4–5.

238. William Walker, Jr., Memoirs of the Distinguished Men of Science (London: W. Walker & Son, 1862), 20.

239. Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), 581.

240. Ibid.

241. Christian Wolmar, The Iron Road (New York: DK, 2014), 22–29; and Francis I:140–141.

242. Francis, I:94–102.

243. Francis, I:292.

244. Ibid.

245. Ibid., 288.

246. Sidney Homer and Richard Sylla, A History of Interest Rates, 4th Ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), 188–193.

247. Bagehot, 138–139. Another factor may have been the compensation due wealthy slave owners, the outcome of 1830s emancipation (personal communication, Andrew Odlyzko).

248. Francis, I:290.

249. Ibid., I:293.

250. Ibid., I:289, 293–294.

251. John Herapath, The Railway Magazine (London: Wyld and Son, 1836), 33.

252. John Lloyd and John Mitchinson, If Ignorance Is Bliss, Why Aren’t There More Happy People? (New York: Crown Publishing, 2008), 207.

253. Francis, I:300.

254. Andrew Odlyzko, “This Time Is Different: An Example of a Giant, Wildly Speculative, and Successful Investment Manias,” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy Vol. 10, No. 1 (2010), 1–26.

255. J.H. Clapham, An Economic History of Modern Britain: The Early Railway Age 1820–1850 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1939), 387, 389–390, 391.

256. Richard S. Lambert, The Railway King (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1964), 30–31.

257. Andrew Odlyzko, personal communication.

258. Lambert, 99–107.

259. Ibid., 150–154.

260. Ibid., 156–157.

261. Ibid., 188–189.

262. Frazar Kirkland, Cyclopedia of Commercial and Business Anecdotes (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1868), 379.

263. Lambert, 173–174; Francis II:237.

264. Lambert, 237. See also Clapham, 391.

265. Francis II:175.

266. Lambert, 165.

267. Francis, II:168–169.

268. Anonymous quote in ibid., 144–145.

269. Quoted in Francis, II:174.

270. Lambert, 168–169.

271. Francis, II:183.

272. Alfred Crowquill, “Railway Mania,” The Illustrated London News, November 1, 1845.

273. Lambert, 207.

274. Lambert, 200–207, 221–240; railway share price index values from W.W. Rostow and Anna Jacobsen Schwartz, The Growth and Fluctuation of the British Economy 1790–1850 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1953), I:437.

275. Francis, II:195–196.

276. Ibid., 275–295; and Andrew Odlyzko, personal communication.

277. John Forster, The Life of Charles Dickens (London: Clapman and Hall, 1890), II:176.

278. William Bernstein, The Birth of Plenty (New York: McGraw-Hill Inc., 2004), 40–41.

279. Charles Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions (London: Office of the National Illustrated Library, 1852), I:84.

280. Andrew Odlyzko, “Charles Mackay’s own extraordinary popular delusions and the Railway Mania,” http://www.dtc.umn.edu/~odlyzko/doc/mania04.pdf, accessed March 30, 2016.

281. Quotes from the Glasgow Argus, October 2, 1845, from Odlyzko, ibid.

282. Andrew Odlyzko, “Newton’s financial misadventures during the South Sea Bubble,” working paper November 7, 2017. The famous quote is secondhand and undocumented.