God’s Sword

The Jews did return to the Holy Land, first as a trickle as the nineteenth century ended, then in increasing numbers as Zionism gained influence in the wake of Eastern Europe’s pogroms, and finally as a flood immediately after the Holocaust.

In the decades following the 1948 birth of Israel, only a small number of its citizens subscribed to the Jewish version of the end-times narrative, which, like the dispensationalist version, also featured the return of the Jews and rebuilding of the Temple. Because of the extraordinarily sensitive nature of the Temple Mount, this tiny group caused, and continues to cause, no end of civil strife that threatens at any moment to explode into a regional, or even a global, conflict.

Christian Zionists, imbued with a dispensationalist fervor that mushroomed during the second half of the twentieth century, proved, and continue to prove, just as dangerous, both inside and outside the Holy Land.

John Nelson Darby and his immediate followers were content to observe events play out from the sidelines, but in the 1930s dispensationalist theology finally collided with realpolitik in the person of a remarkable British army officer named Orde Wingate—“Lawrence of the Jews,” as described by the famous British military historian Basil Liddell Hart.492

In 1920, the League of Nations granted Britain custodial rule over the Holy Land—the British Mandate for Palestine—where Wingate served between 1936 and 1939.493 There, his dispensationalist beliefs combined with his military skill and British resources to move the millennium along; unfortunately, he did so by grossly violating the Mandate’s supposed equal treatment of Arabs and Jews.

Wingate’s maternal grandfather was a Scottish captain in the British army who resigned his commission to found a local chapter of the Brethren, and both of his parents were also members. Young Wingate grew up listening to his father’s dispensationalist church sermons, and his mother was even more doctrinaire. In 1921, he joined the army, and in 1936, he was fatefully deployed to Palestine, where the Old Testament became his field manual. The great Israeli general Moshe Dayan describes their first meeting:

Wingate was a slender man of medium height, with a strong, pale face. He walked in with a heavy revolver at his side, carrying a small Bible in his hand. His manner was pleasing and sincere, his look intense and piercing. When he spoke, he looked you straight in the eye as someone who seeks to imbue you with his own faith and strength. I recall that he arrived just before the sunset, and the fading light lent an air of mystery and drama in his coming.494

His arrival in Palestine coincided with a violent series of Arab attacks on both Jewish settlements and British Mandate troops, charged with keeping the Arabs and Jews from each other’s throats. Wingate’s single-minded sympathy for the Jews soon disturbed the fragile diplomacy required for this task and annoyed his commanders, who tended to be pro-Arab.

Wingate thought the Jews too passive in the defense of their settlements against Arab raids and urged them to go on the offensive. He had a career-long fondness for commando-style raids behind enemy lines; although initially assigned as an intelligence officer, he soon formed the Special Night Squadrons (SNS), a unit of around two hundred men, three-quarters of whom were Jewish, commanded by British officers. The unique unit was tasked with protecting the strategically important oil pipeline that ran from Iraq to the Mediterranean. In the summer of 1938, the SNS conducted a series of largely successful raids against Arab forces.

As hinted at by Dayan, to call Wingate eccentric would be an understatement. He was given to addressing his troops stark naked or wearing only a shower cap, and occasionally scrubbed himself as he spoke. He also consumed large amounts of raw onions and repeatedly exposed himself and his troops to contaminated food and water in the belief that this increased disease resistance.

Wingate’s family’s dispensationalist theology drove his actions in Palestine; he once told his mother-in-law that “The Jews should have their homeland in Palestine and that, in this way, the prophecies of the Bible would be fulfilled.”495 Wingate was also not averse to combining his biblical aspirations with more earthly ones, as he viewed a militarily strong Jewish people as a bulwark of the British Empire.

His pro-Zionist bias soon earned him the enmity of both the Arabs, who put a price on his head, and of his superiors, who found his hit-and-run tactics and “dressing up Jews as British soldiers” unsporting. Eventually, the brass confined him to desk work in Jerusalem and then in May 1939 reassigned him to antiaircraft duty in Britain.496 He remained there only a short time before the Second World War began, upon which he was sent to Sudan and then Ethiopia to lead the “Gideon force,” a guerrilla unit that harassed the region’s Italian occupiers. The outbreak of the Pacific war saw him transferred to Burma, where he organized his most famous behind-the-lines unit, the Chindits (also known as “Wingate’s Raiders”), whose British army commandos harassed Japanese forces in the effort that protected the subcontinent from invasion. On March 24, 1944, he died in a plane crash in India.497

Wingate had not only disturbed the neutrality of the British Mandate, but at least as important, he had egregiously breached the dispensationalist injunction against actively working to bring about the end-times through his SNS operations, whose tactical brilliance awed his Jewish subordinates. He mentored almost the entire cohort of Israeli high commanders in the coming 1948 War of Independence and in the 1967 Six-Day War, including Moshe Dayan, Yigal Allon, Yigael Yadin, and Yitzhak Rabin. He also helped bring about what is today known in Middle East politics as “facts on the ground”—conquered territory and established settlements.498 In Dayan’s words, “Wingate was my great teacher. His teaching became part of me and was absorbed into my blood.”499 One does not have to travel far in Israel to see streets and public places named after him, as is a training center for the country’s national sports teams.

He had planned to resign his British army commission at war’s end and return to Palestine; David Ben-Gurion, the nation’s founder, thought him the “natural choice” to command the Israeli forces.500 His counterfactual survival is surely one of the great what-ifs of Middle East history: Would a Wingate-led Israeli army have held on to Jerusalem’s Old City during the War of Independence? Would his charismatic leadership have led to a more complete victory in that war and possession of the West Bank in 1948, or would his notoriously erratic personal behavior have proven fatal for the nascent Jewish state?

Wingate’s ghost haunts the Middle East down to the present. In September 2000, Ariel Sharon, acting in his capacity as leader of the opposition Likud Party and surrounded by nearly a thousand armed riot police, single-handedly sparked the deadly Second Intifada and derailed the Oslo Accords with a visit to the Temple Mount. Wingate was Sharon’s boyhood hero; further, he had trained and commanded a young soldier named Avraham Yoffee, who in turn became Sharon’s mentor.

Sharon’s fateful visit to the Temple Mount brings into focus its status as the world’s most contentious piece of real estate, a 35-acre tract in Jerusalem’s labyrinthine 220-acre Old City, which itself is intimately bound up in the end-times narratives, and thus the religious manias, of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. It is thus arguably the place where the Third World War is most likely to begin, with Jewish, Christian, and Muslim millennialists as the dramatis personae.

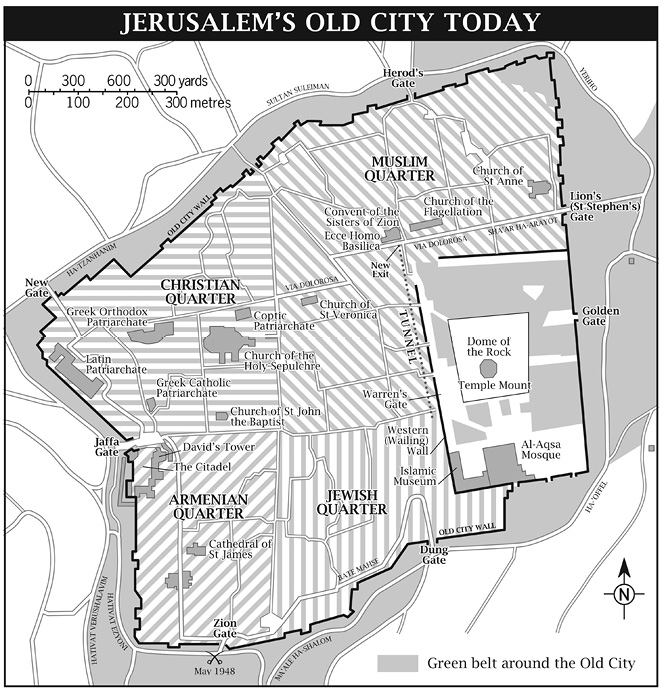

Roughly speaking, the Old City can be envisioned as a square with the Temple Mount at its southeastern corner. As one circles the Old City’s perimeter in a clockwise direction from the Mount, one passes successively through the Jewish, Armenian, Christian, and Muslim quarters before arriving back at the Mount, which is where Christian and Jewish religious extremists, each with their own apocalyptic scripts, want to build the Third Temple.

No one is certain precisely where the First Temple, built by Solomon and destroyed by the Babylonians, was located, but the Mount’s Dome of the Rock shrine is the most commonly mentioned site. (And even before the Jews occupied Canaan, it was likely a place of worship of the Jebusites, whom Solomon’s father, David, had conquered.) The Second Temple was constructed after the return from the Babylonian exile in the late sixth century b.c., restored and expanded under the Maccabees, and massively enlarged into the current Temple Mount site by Herod before being destroyed by the Romans in a.d. 70.

The Arabs conquered Jerusalem in a.d. 637 and completed the Dome of the Rock in a.d. 692. The Mount’s second major structure, the al-Aqsa Mosque, started as a simple shack and was reconstructed several times after earthquakes before taking its final form around 1035. The holiness of the Mount to Muslims derives from a dream of the Prophet’s in 621 in which he visited it, as well as heaven, in a single night on Buraq, his winged steed. (Upon his “return” to Mecca the next day, Muhammad offered the account of his supposed journey to the city’s skeptical inhabitants.)

Jewish religious scholars divide into three different groups over the current status of the Temple Mount. The first, and largest, group considers it permissible for Jews to visit the Temple Mount but not to pray there. A second, smaller group considers even a visit forbidden, since not only is the sacrificial red heifer missing, but so is knowledge of the precise location of the Ark of the Covenant (the Holy of Holies). According to this second group, visitors are thus impure and might accidentally contaminate the Ark, wherever it actually happens to be located within the Mount. Finally, a tiny minority on the far-right fringe wants to build the Third Temple. Right now.501

Theological considerations aside, the overwhelming majority of Jews don’t want to rebuild the Temple for one good, practical reason: It would necessitate razing the Dome of the Rock and possibly the al-Aqsa Mosque, and no great geopolitical acumen is required to realize that the willful Jewish demolition of these structures would trigger a cataclysmic regional, and possibly a worldwide, conflict.

The Brethren and early dispensationalists had relatively little to say on this contentious subject, and for good reason: As they often do, the Old and New Testaments offer conflicting advice regarding the future temple, or, more precisely, on the necessity to perform sacrifices there. On the one hand, Ezekiel 40–48 describes a future temple, and the sacrifices to be performed within; and on the other hand, Hebrews 10:1–18 argues that the Messiah’s sacrifices sufficed, and that animal sacrifices, and hence the rebuilding of the Temple, are unnecessary.502

The long and tangled history of Jerusalem suffuses the explosive modern status of the city. In a.d. 70 the Romans destroyed the Temple and expelled much of the rebellious Jewish population, and most of the remainder in a.d. 135 after a second revolt led by Simon bar Kokhba. The city was then occupied, sequentially, by the Romans, Byzantines, Sasanian Persians, and the Muslim Umayyad, Abbasid, and Fatimid Caliphates. In 1099, the crusaders ejected the Fatimids and slaughtered the city’s Jewish and Muslim inhabitants; the crusaders then temporarily lost the city to Saladin in 1187, and decades of seesaw control between Christian and Muslim forces ensued. In the last half of the thirteenth century, the Muslim Mamluks and Mongols dueled for control of the city, but after about 1300 the Mamluks won out and so ushered in over six centuries of uninterrupted Muslim rule. The Ottomans took over from the Mamluks in 1516 and retained control until December 1917, when British forces under General Edmund Allenby entered the Holy City.

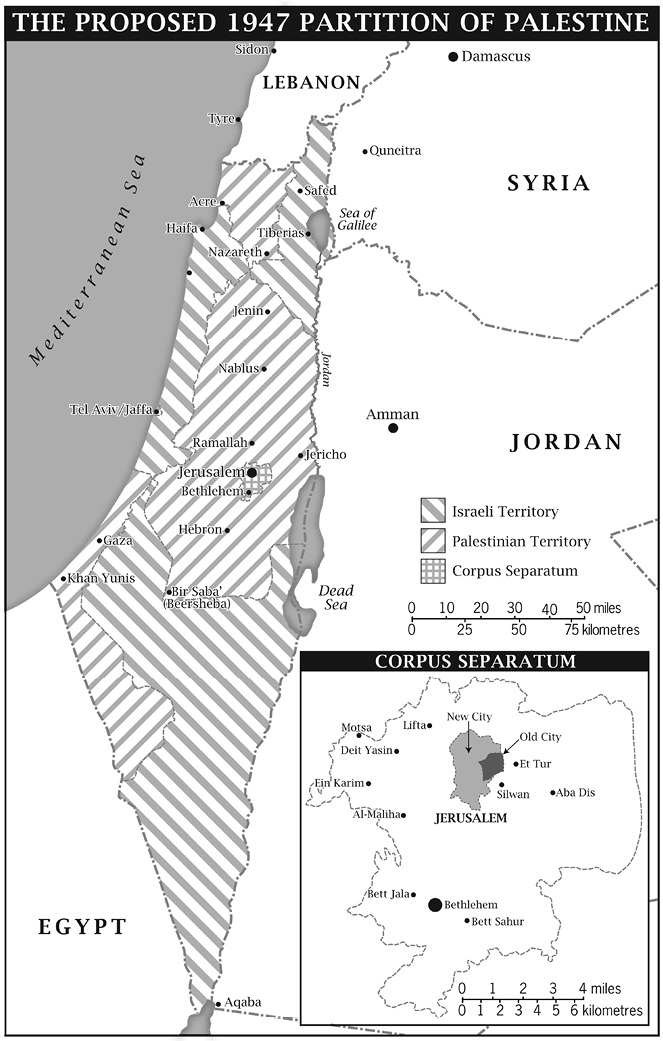

Around 1929, six years after the Mandate’s establishment, Jews and Arabs began slaughtering each other in incidents ranging from attacks on single individuals to large-scale riots and terrorist operations, and the carnage continued throughout the 1930s as the Arabs reacted violently to the large numbers of newly arrived Jewish immigrants fleeing Nazi persecution and in the aftermath of the Holocaust. The United Nations offered a partition plan for the territory in 1947, but when the Jews declared the establishment of the state of Israel at midnight on May 14, 1948, full-scale war broke out between the new nation and its Arab neighbors.

The partition plan, which divided Palestine roughly in half, also envisioned an internationally administered greater Jerusalem, a “corpus separatum” of about a hundred square miles, which would include the Old City, the more modern precincts to the west, and the surrounding territory.

The Palestinians and adjacent Arab countries rejected the partition and would settle for nothing less than the complete destruction of the new Jewish state. Both Arabs and Jews attacked Jerusalem at the moment of independence on May 14, 1948, from multiple directions.

In a critical battle at the Old City’s southern entrance, the Zion Gate, Jewish forces under the command of a twenty-two-year-old officer named David Elazar penetrated the entrance long enough to extract the Jewish Quarter’s civilians and wounded military personnel. The attack exhausted Elazar’s unit, and the less well trained one that replaced it was forced to withdraw and left the Old City in the hands of the Jordanians.503 Until that point, Jews had resided there more or less continuously for three millennia. Even under Muslim rule, Jews had access to the Temple Mount and, critically, its Western Wall, the holiest site in Judaism. The Jordanian forces proceeded to level the Jewish Quarter. Despite the loss of the Old City, the new nation survived, contrary to the expectations of the international community and also of many Jews.

The initial reaction of American Christians to Israel’s founding was tepid at best. American Catholics, for example, followed the Vatican’s lead in denying any Jewish claim to the Holy Land. In 1943, the Vatican’s secretary of state declared that it did not recognize the Balfour Declaration, and on the same day that Israel announced its independence in 1948, the Vatican’s newspaper, L’Osservatore, claimed, “Modern Israel is not the heir to biblical Israel. The Holy Land and its sacred sites belong only to Christianity: the true Israel.”504

Mainstream Protestants were hardly more enthusiastic; they largely agreed with the Vatican that Christians, not Jews, represented the new Israel. Further, Episcopalians and Presbyterians had other reasons to favor the Arab cause over the Jewish one. They worried that American support for the new Jewish state would hamper their missionary activity in the Arab world as well as their educational institutions, particularly the American Universities in Beirut and Cairo, which had by that point become hotbeds of Arab nationalism. Last and not least, Episcopalians and Presbyterians packed the executive suites of oil companies with increasingly lucrative and strategically important potential Middle Eastern operations.505

During the early twentieth century, the American Protestant establishment publication Christian Century emitted a constant stream of anti-Zionist editorial opinion. For example, in 1929 it questioned:

The Jew is respected and honored in all the regions where he has exhibited his powers in the fields of industry, commerce, politics, art and literature. Does he really desire to emigrate to a small, poverty stricken and unresourceful land like Palestine?506

Most egregiously, when Hitler took power in 1933, most mainstream Protestants looked the other way. As Nazi racial legislation gave way to outright genocide, Christian Century repeatedly counseled against a rush to judgment; more data were needed, its editors thought. A decade later, the publication urged Jews to bring Jesus back into their synagogues after his two-millennia absence and thus demonstrate their fealty to the United States, “a simple gesture [of which] would be the unconstrained observance of Jesus’ birthday.”507

In 1942, the first stories about deportations, concentration camps, and mass killings began to appear in American newspapers, and when the American Zionist rabbi Stephen Wise began to publicize their full extent, Christian Century questioned whether his charges served “any good purpose.” The publication was particularly outraged by Wise’s assertion, later proved tragically true, that Jewish corpses were occasionally being processed into soap.508

Not all mainstream Protestants proved so oblivious to the truth, most notably the great American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. As with many of his political analyses, his early observations on a Jewish state have endured well and speak volumes to the current Middle East situation. As a liberal Protestant, Niebuhr rejected the Bible’s literal truth and took a more realistic and pragmatic approach to the Zionist question. Writing early in the Second World War, he observed that the Jews deserved nationhood, not to bring about the millennium, but for more down-to-earth reasons. First, “every race finally has the right to a homeland where it will not be ‘different,’ where it will neither be patronized by the ‘good’ people nor subjected to calumny by bad people.” Second, it was painfully apparent that no one nation could absorb all of the refugees from Nazi oppression, and that Palestine would serve as a necessary safety valve for the overflow.509

Critically, unlike Wingate and the Christian Zionists, Niebuhr recognized that it was folly to ignore the Arab population:

[The American and British eventual victors of the Second World War] will be in a position to see to it that Palestine is set aside for the Jews, that the present restrictions on immigration are abrogated, and that the Arabs are otherwise compensated. Zionist leaders are unrealistic in insisting that their demands entail no “injustice” to the Arab population since Jewish immigration has brought new strength to Palestine. It is absurd to expect any people to regard the restriction of their sovereignty over a traditional possession as “just,” no matter how many benefits accrue from that abridgement.510

Like most dispensationalists, the brilliant Yiddish-speaking Arno Gaebelein differentiated between Orthodox Jews, whom he revered, and more secular Jews, whom he regarded with suspicion. A virulent anti-Communist, he fell for the most notorious of all anti-Semitic frauds, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which bruited a vast Jewish conspiracy to control the global economy, take over national governments, and kill Christians (and which has recently been resurrected by the current global crop of extreme-right nationalists).

At the same time, Gaebelein proved spectacularly prescient about the Holocaust at a time when most mainstream Protestants and Catholics had averted their gazes. As early as 1932, he condemned Hitler’s rabid anti-Semitism and predicted that “he evidently is headed for the end and the same fate as Haman in the Book of Esther.” By 1942, he was one of the earliest to relay reports of mass murder in occupied Europe and of Hitler’s desire to exterminate the Jewish people; by the next year he correctly approximated that by that point the Germans had killed two million of them.511

The fault line between fundamentalist and mainstream Protestantism at Israel’s birth played out at the highest levels in 1948 in the persons of Harry Truman, a Baptist who had read the entire Bible twice by age twelve, and his secretary of state, George C. Marshall, an Episcopalian.512 Two days before the end of the British Mandate, Truman met with Marshall, Under Secretary Robert Lovett, and a young Clark Clifford, the White House counsel.

Truman had already promised Chaim Weizmann, by now the president of the Zionist Organization, U.S. recognition of Israel, and asked Clifford to present the case for doing so to Marshall and Lovett. Before Truman even got started, Marshall interrupted the president: “I don’t even know why Clifford is here. He is a domestic adviser and this is a policy matter,” to which Truman responded, “Well, General, he’s here because I asked him to be here,” to which Lovett, who had been a Skull and Bones member at Yale and whose father had been chairman of the Union Pacific Railroad, added that recognizing Israel was “obviously designed to win the Jewish vote.” Truman and Marshall went at each other for a while longer before Marshall finally declared, “If you follow Clifford’s advice, and if I were to vote in the election, I would vote against you.”513

Eventually, Marshall backed down and promised to keep secret his opposition to the recognition of Israel. Truman had been born to devout Baptist parents, regularly attended Sunday school, and rebaptized himself as an adult; no matter where he was, he almost always attended Sunday services. In his personal papers, he recorded, “I’m a Baptist because I think that sect gives the common man the shortest and most direct approach to God.”514

Shortly after he left the White House, he visited the Jewish Theological Seminary, where a friend introduced him as “the man who helped create the state of Israel.” Truman responded by referring to the Persian king who had released the Jews from Babylonian captivity, “What do you mean ‘helped to create’? I am Cyrus. I am Cyrus.”515

The 1949 armistice agreements left the Old City and the West Bank in Jordanian hands; at its narrowest point, Israel’s “waist,” the distance between Jordanian troops and the sea, spanned just nine miles. Jerusalem’s newer western half remained under Israeli control, but the Jordanians held Latrun, just a stone’s throw from the critical road that ran through the neck of territory that connected the New City with the rest of Israel. During the Independence War, Latrun had been the site of a ferocious battle that ended in defeat for the Israelis, following which they built a new road a few miles to the south that rendered the link only slightly less vulnerable.

In contrast to their mainstream Christian cousins, American dispensationalists reacted ecstatically to Israel’s establishment. Typical of these was Schuyler English, who had attended Phillips Academy and Princeton and spoke Hebrew and Aramaic, headed the Philadelphia School of the Bible, and later spent more than a decade working on the 1967 edition of the Scofield Reference Bible. In 1949, he declared that “the Messianic age is about to begin.” Further, he detected an “imminent alliance” between Israel and Britain as the start of the dispensationalist compact between the Jews and the restored Roman Empire. That the British might not be eager to ally with Zionists who had heretofore been blowing up their soldiers seemed to have escaped him. Other dispensationalists went further and concluded that God had intentionally shortened the life of Franklin Roosevelt, who had developed close relations with the Arabs, in order to make the pro-Israel Harry Truman president.516

While the establishment of Israel certainly stirred the souls of bookish dispensationalists, it resonated little beyond their rarified circle, of whom Schuyler English was typical. Further, although the founding of Israel had returned the Jews to the Holy Land, they didn’t control the Temple Mount, and in fact for the first time in millennia no longer even had access to it. They thus were in no position to fulfill an essential dispensationalist requirement: the resumption of worship and sacrifices in a rebuilt Third Temple.

Nineteen years later, that would change. In May 1967, as Arab mobs filled the streets and demanded Israel’s destruction, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser blockaded Israel’s access to the Red Sea and expelled United Nations peacekeepers from the Sinai Peninsula. (The Israelis had conquered the Sinai during their brief 1956 military alliance with the French and British. The peninsula was returned to Egypt under a subsequent agreement, according to which both of Nasser’s actions constituted acts of war.) Critically, Nasser also sent two commando battalions to Latrun, a dagger aimed directly at Israeli west Jerusalem; at the end of May, he publicly announced that he would destroy the Jewish state.

Nasser calculated that this provocation would yield an Israeli attack, which would end in the tiny country’s liquidation by superior Arab forces. He was half right. The six days from June 5 to June 10 saw the Israeli armed forces destroy the Egyptian air force on the ground and occupy the Sinai, West Bank, Golan Heights, and the Old City and Temple Mount.

Initially, the Israelis had not planned to take the Old City. The nation felt itself on the brink of annihilation, and the existential threat from Egypt demanded their full attention and resources. The nation’s leadership thus desperately sought to keep the Jordanians, who could cut Israel in two at its vulnerable “waist,” out of the war. To the extent that the Israelis had any strategic interest in the Jerusalem area, it centered on the Mount Scopus enclave, with its small garrison and abandoned university and hospital, which were completely surrounded by Jordanian territory.

The Israelis relayed a message to Jordan’s King Hussein that if he avoided hostilities, they would not attack his forces on either side of the Jordan River. He replied that his answer would be “airborne,” and it soon came via fighter aircraft and artillery strikes. Hussein’s aircraft proved ineffective, but when the Jordanians shelled Jerusalem and the nation’s international airport outside Tel Aviv, the Israelis had little choice but to respond. Even at that point, Moshe Dayan, who had become defense minister just three weeks before in response to the crisis, wanted to proceed carefully, but the cabinet’s hawks, particularly Menachem Begin, demanded that the army take Jerusalem; for the first two days of the war, Dayan’s restraint won out.517

It is hard to imagine anyone better equipped than Moshe Dayan to deal with the evolving dynamic in the Old City. The one-eyed defense minister grew up on a farm in everyday contact with Arabs, spoke Arabic, developed boyhood friendships with them, and admired their parents’ quiet dignity. During the War of Independence, the young lieutenant colonel had commanded Jewish forces in the Jerusalem area. In the midst of the delicate and prolonged armistice talks that eventually ended the 1948 conflict, he had dealt extensively, and increasingly warmly, with his Jordanian counterpart Abdullah el-Tell, whom Dayan trusted enough to travel with, dressed in Arab garb, to Amman, where he negotiated with King Abdullah, Hussein’s father; years later Dayan returned the favor when el-Tell requested that the Palestine Post (predecessor of the Jerusalem Post) pen scathing criticisms of him and so enhance his credibility in Amman.518

With the Egyptian and Jordanian threats neutralized and a cease-fire imminent, the Israeli cabinet finally authorized the taking of the Old City; the local commander, Uzi Narkiss, who had fought in the unsuccessful 1948 battle for the Old City, ordered Mordechai Gur, a paratroop officer, to execute the final assault.

Gur, whose reservist unit had initially been scheduled to deploy into the Sinai, proceeded to fight a series of bloody battles with Jordanian forces to secure the Old City’s northern and eastern outskirts, an approach that had the added advantage of establishing a corridor to Mt. Scopus. Israeli aircraft scattered a westbound relief column urgently requested by the Old City’s Jordanian garrison, which allowed Gur’s paratroopers relatively easy final entry through its gates on June 7. Dayan, mindful of world opinion, authorized no air cover over the Old City, kept artillery rounds away from the Temple Mount, and directed sparse small-arms fire only at snipers in the al-Aqsa minaret.519 That was fortunate: The Jordanians had stored a massive amount of munitions adjacent to the Mount, which close fighting would likely have ignited, with catastrophic geopolitical results.520

Gur, upon occupying the world’s most sacred site, radioed to Narkiss perhaps the most famous sentence in the modern Hebrew language, “Har HaBayit BeYadeinu!” (“The Temple Mount is in our hands!”) Two officers followed Gur to the Mount: Narkiss and the ecstatic Shlomo Goren, the army’s chief rabbi since independence, who ascended the Mount shouting biblical verses and repeatedly blowing his ram’s horn trumpet (shofar).

Goren belonged to the small Jewish minority who wanted to rebuild the Third Temple. He took Narkiss aside to talk. Only decades later, just before he died, did Narkiss give this account of the exchange to the newspaper Haaretz:

Goren: Uzi, now is the moment to put 100 kilograms of dynamite into the Mosque of Omar [the Dome of the Rock] and that will be it.

Narkiss: Rabbi, stop.

Goren: Uzi, you enter the pages of history for such an act. You don’t grasp the very important implications for such an action. This is an opportunity which it’s possible to exploit now at this moment. Tomorrow, it won’t be possible to do anything.

Narkiss: Rabbi, if you don’t stop, I will take you from here to prison.521

Goren left in silence. As soon as he heard the news of the Old City’s capture, Dayan headed for Jerusalem to deal with the Temple Mount situation, then as now the fuse attached to the time bomb of Middle East politics.

As Dayan described in his memoirs,

For many years, the Arabs had barred Jews from their most sacred site, the Western Wall of the Temple compound in Jerusalem, and from the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. Now that we were in control, it was up to us to grant what we had demanded of others and to allow members of all faiths absolute freedom to visit and worship in their holy places.522

Immediately after he arrived on the Mount, Dayan ordered the Israeli flag removed from the Dome of the Rock. The next day he consulted with a Hebrew University professor of Islamic history on how best to approach the clerical officials who ran the site, the Waqf. Shortly thereafter, he and his staff found themselves ascending the Temple Mount toward the al-Aqsa Mosque for a fateful meeting:

As we continued [upward] to reach the mosque compound, it was as though we . . . had entered a place of sullen silence. The Arab officials who received us outside the mosque solemnly greeted us, their expression reflecting deep mourning over our victory and fear of what I might do.523

Dayan ordered his soldiers to leave their shoes and weapons at the door, and after hearing the initial orientation from the Waqf, asked them to speak of the future. They greeted this request with silence, and so he and his staff sat on the floor cross-legged, in Arab style, and made small talk. Eventually, the officials opened up: Their immediate concern was the cutoff in water and electricity attendant to the battle. Dayan promised them both back within forty-eight hours.

At that point he told the Waqf why he had come: his soldiers would depart the Mount, which he would leave in their hands. Dayan asked that they resume services, and told them that the Israelis would not censor the traditional Friday sermon, as had the Jordanians. His forces would secure the Mount from without, and the Western Wall, the holiest site in Judaism, which bulldozers had just cleared of adjacent Arab dwellings, would remain in Israeli hands.

Dayan later recorded, “My hosts were not overjoyed with my final remarks, but they recognized that they would not be able to change my decision.”524 A prodigious womanizer and archeological thief, Dayan was no angel. Observed journalist Gershom Gorenberg, “If God does stick his finger in history, He has a sense of humor in His choice of saints.”525 Dayan had come up with this arrangement on his own, with little input from the cabinet; as is usually true of prudent and enduring compromises, neither side was happy with it.

Nonetheless, the hastily brokered state of affairs has yielded an incessant series of incidents, each of which has carried the potential for catastrophe. Almost from the start, Rabbi Goren proved troublesome. He started by bringing small groups of followers up to the Mount to pray. Initially, the Waqf did not object, but on the ninth of the month of Av, when Jews commemorate the destruction of both temples, he pushed the envelope yet further. On that day, which fell on August 15, 1967, the nettlesome rabbi brought to the Mount fifty people and a portable Ark, blew his ram’s horn, and prayed.

The city’s Muslims grew agitated, and the Waqf locked the main entrance to the Mount and began to charge Jews an entrance fee; Goren responded by promising to bring a thousand followers the following Sabbath. By this point the Israeli cabinet had tired of Goren’s antics and decided that while Jews could visit the Mount, they could not pray upon it, and almost simultaneously, the Chief Rabbinate, Israel’s supreme religious council, forbade Jews to visit it at all. Although not all Jews recognized the Rabbinate’s authority, a large portion of the Orthodox did, and since they tended to be the most ideologically extreme, this prohibition kept the lid on Mount-related tension—at least for a while.526

The small minority of Jews who wanted to evict the Muslims from the Mount, dynamite the Dome and the Mosque, and rebuild the Third Temple were outraged and labeled Dayan a traitor and worse. Although history has thus far vindicated Dayan, the last has not yet been heard from temple-building zealots or from the Waqf.

Almost from the start, Dayan’s compromise largely nullified Gur’s famous exclamation; on a day-to-day basis, the Temple Mount is in fact in the hands of the Muslim community, and that control has only solidified over the half century since the 1967 war, and the political volatility surrounding God’s little thirty-five acres has only increased along with it.

The next major incident at the Mount involved a schizophrenic Australian Christian named Denis Michael Rohan, who, suffused with psychosis-derived religious fervor, entered the al-Aqsa Mosque on August 21, 1967, poured kerosene onto the stairs to the pulpit, and tossed in a match. The fire destroyed much of the interior and weakened supporting pillars.

Rohan was a disciple of Herbert Armstrong, the American founder of the fundamentalist Radio Church of God, one of the first preachers to exploit the new medium in the early 1930s. Armstrong wasn’t a dispensationalist, but rather believed that Britons and Americans were descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Judaism. Nonetheless, the garden-variety dispensationalist belief that the Second Coming of Jesus required renewed worship and sacrifices at a rebuilt Temple motivated the actively hallucinating Rohan, who simply took the next logical step: since the Mosque was the site of the First Temple, it had to be destroyed to make way for the new Temple’s rebuilding (despite the fact that most authorities place the site of the First Temple at the Dome of the Rock, not at the adjacent Mosque).

When Israeli police finally caught up with Rohan two days later at his east Jerusalem guesthouse, he cheerfully confessed that since God wanted him to build the Temple, he had to first destroy the Mosque. In the end, Rohan was tried, convicted, confined to psychiatric detention, and finally in 1974 deported to Australia, where he remained hospitalized for two decades until his death.

Despite Rohan’s lack of a Jewish connection, the Arab world erupted; both Nasser and Saudi King Faisal declared a sacred war against Israel. In this particular instance, the Israelis were lucky, since both Nasser and Faisal had locked up the radical Islamists most likely to take up the call.527

The al-Aqsa Mosque fire illustrated the two most explosive characteristics of Temple Mount politics. First, it is everywhere and always suffused with paranoia; despite Rohan’s manifest insanity and lack of Zionist connections, many in the Arab world still accused the Jews of setting the fire and Israeli firemen of pouring gasoline on it. Contrariwise, one Israeli cabinet minister accused Muslims of setting the fire as a provocation. Second, if the Temple Mount tinderbox ever sets the world alight, it will likely be with the flame of religious delusion, whether that of the Zionist extremist, radical Islamist, dispensationalist Christian, or merely an everyday schizophrenic. Their madness will offer little solace for the ensuing Armageddon.

It is probably not too much of an overgeneralization to apply this principle to all of the world’s great faiths. Mainstream Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are all religions of peace until they fall into the hands of the deluded true believer or the overtly insane; as regards the latter, schizophrenia’s cardinal symptom, auditory hallucination, often speaks in the voice of God.528

Christians hardly possess a monopoly on end-times delusions, and the Jews had a half-millennium head start in that department. Islam, starting almost with the Prophet himself, has also sprouted its own varieties, which have recently mushroomed in both the bookstore and on the battlefield.

Desperation is the fertile soil in which end-times narratives grow, and in the sixth century b.c., having just been exiled into servitude along the shores of the Euphrates, the ancient Jews were certainly in need of a break. The books of Ezekiel and Daniel bruited the destruction of the Jews’ oppressors, but theologians generally mark the first explicit mention of the Jewish Messiah with the Book of Isaiah. Similar to Daniel, Isaiah was written centuries after he supposedly lived in the eighth century b.c., probably by a series of authors writing both during the Babylonian exile and after the return to Judah. Its chapters prophesized the appearance of a savior who would end time and institute a universal Kingdom of God in Jerusalem.

Messianism runs as a constant theme throughout Jewish history, sometimes as a thin red ribbon, other times as an unfurling crimson cloth that smothers reason. It could become a nationwide movement, as during the Roman period when the Zealots plotted the a.d. 70 rebellion in which a Zealot splinter group, the Sicarii, assassinated Jews who refused to rebel; some of its members later committed mass suicide at Masada, high above the Dead Sea. Or it could be the work of talented but deluded, and occasionally psychotic, individuals such as Sabbatai Zevi, a bipolar Sephardic rabbi who declared himself the Messiah in 1648 during a manic break, became the religious leader of the large Jewish community of Smyrna in Asia Minor, then skittered around the eastern Mediterranean gathering converts and congregations. The mid-seventeenth century saw pogroms that decimated the Continent’s Jewish population, and Sabbatai Zevi’s messianic promises of salvation attracted a vast following that ended when he was imprisoned by the Ottomans and chose conversion to Islam over death.529

In the aftermath of the Holocaust, the fractious Israeli independence movement featured its own version of the drama between the ancient Judean Zealots, who generally didn’t murder their fellow Jews, and the Sicarii, who did. During the pre-Independence conflicts, two terrorist groups, the Irgun and Lehi, would, respectively, reenact these two roles. Each participated in murderous attacks on both Arabs and British officials, most famously the 1944 assassination in Cairo of Lord Moyne, a British deputy minister of state, and the 1946 bombing of Jerusalem’s King David Hotel, which killed ninety-one people.

When the Second World War erupted, the Irgun called a temporary halt to its attacks on the British, which angered its more radical members, who coalesced under the leadership of Avraham Stern to form Lehi (better known in the English-speaking world as the Stern Gang). Like the Irgun, Lehi targeted Arabs and British nationals and was responsible for not only Moyne’s assassination, but in 1948, that of Count Folke Bernadotte, the U.N. representative, whom they feared was about to push through an unfavorable armistice settlement with the Arabs. (During the war, Bernadotte had secured the release of tens of thousands from German concentration camps, among whom were about sixteen hundred Jews.)

In addition to the temporary Second World War cease-fire with the British, two issues separated the Irgun and Lehi. As with the Zealots and their splinter Sicarii faction, the Irgun generally did not kill their fellow Jews, whereas the Lehi did. Both the ancient Sicarii and modern-day Lehi murdered Jewish collaborators, and occasionally those with whom they merely had ideological differences. More importantly, like the Sicarii, the Lehi were enthusiastic messianists, whereas the Irgun were more secular.

Lehi’s manifesto, the “National Revival Principles,” listed eighteen points, which included the infamous promise to the Jews from Exodus of the land “from the River of Egypt to the great Euphrates River,” and also the building of the Third Temple.530 The last leaders of the Irgun and Lehi, before being absorbed into the Israeli armed forces and intelligence services, were, respectively, Menachem Begin and Yitzhak Shamir. Both later became Israeli prime ministers.

Messianic groups garner relatively little support in Israel, where the populace is well informed, and there are few ruder things than phoning someone during the evening news; their body politic thus well understands the suicidal potential of rebuilding the Temple. While the nation is still the target of frequent terrorist attacks and of the more recent looming Iranian presence, the raw fuel for messianism, an existential threat on the scale of the Babylonians, Seleucids, Romans, Nazis, or Nasser’s Egypt, is no longer present; Israel, after all, has signed peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan, and the remaining traditional threat, Syria, is in disarray.

Even so, the 1967 conquest of the Old City did energize a small corner of Israeli millennialists, especially the Gush Emunim (Bloc of the Faithful), who took Exodus’s territorial maximalism as gospel: The Lord had deeded Gaza, the West Bank, the Golan Heights, and even the desolate Sinai to the Jews in perpetuity. Almost immediately after the 1967 war, the Gush began building settlements in the West Bank, and in 1974, they clashed with the new prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, over building projects there; eventually, the settlers wore the prime minister down and outfoxed him with an end run through Rabin’s rival, defense minister Shimon Peres, who was more sympathetic to the settlements. Three years later, Menachem Begin became the Israeli leader, and he opened the floodgates to West Bank expansion. (Gush was less successful in preventing implementation of the 1978 Camp David Accord, which returned the Sinai to Egypt.)

Other Jewish messianists focused on rebuilding the Temple. One such Temple enthusiast is Yisrael Ariel, the rabbi intrigued by Melody the cow. As a young man in 1967, Ariel had served in the paratroop brigade that captured the Western Wall. For him and a tiny group of ultra-Orthodox Jews, the Messiah (the first, and as yet unarrived, one) cannot come until the Temple is up and running, and in 1988, he helped found the Temple Institute, which is dedicated not just to rebuilding the Third Temple, but also to recreating it down to the finest detail, including the flaxen robes, musical instruments, and rituals of ancient Jewish worship.

Such attention to detail is simply a matter of time, artistry, and money, of which Ariel and his colleagues have plenty. More difficult to accomplish is supplying the priests who will perform the ritual sacrifice required for the Messiah’s return. This represents a theological catch-22, since sacrifices generally can be performed only by a priest purified with red-heifer ash, which itself requires slaughtering the rare bovine.

Yosef Elboim, a rabbi associated with another messianic group, the Movement for the Establishment of the Temple, sought to surmount this difficulty through the creation of priests who have never been under the same roof with a dead person. Willing expectant mothers descended from the ancient priestly caste, the cohanim, would give birth in a special compound, raised off the ground so as to avoid another priestly taboo, mistakenly stepping on an unmarked grave. The Movement would allow parental visits, but the boys could never venture outside the compound; a specially raised courtyard would be provided for play. They would receive priestly training, including sacrificial technique, and at some future date after their bar mitzvahs they would slaughter genetically engineered red heifers.531

In 1975, a small group of Jewish messianists entered the Temple Mount and prayed just inside one of the gates forbidden to them, as had Goren and his followers eight years previously.532 A joint Arab-Israeli police unit removed the praying nationalists, but an Israeli court ruled in favor of their actions and provoked riots in which several Arabs were killed and dozens injured. Arab nations protested at the U.N., and the Waqf ruled that the entire Mount, including the Western Wall, was a mosque. An Israeli higher court finally nullified the decision to allow Jewish Temple Mount prayer, but subsequently three Likud prime ministers, Menachem Begin, Ariel Sharon, and Benjamin Netanyahu, have vowed to reverse it. None has yet delivered on that incendiary promise.

In 1982, two separate Jewish extremist groups attempted to plant explosives on the Mount; in the first, the Kach movement, a floridly racist anti-Arab group led by Rabbi Meir Kahane, tried to set off a bomb near the wall of the Dome of the Rock, while the second, a shadowy group called the Lifta Gang, attempted to blow up both the Dome and the al-Aqsa Mosque.533 In response to the attempts, the Harvard University Center for International Affairs performed a geopolitical simulation predicated on a successful destruction of the Dome and concluded that it would start a third world war.

Yet more seriously, another group, the Jewish Underground, which had by the early 1980s killed five Arab students in Hebron and had attempted assassinations of West Bank mayors and bombings of mosques and Arab buses, made the most serious attempt of all. In 1984, they performed extensive reconnaissance of the Dome and acquired sophisticated explosives before calling off their plans. As later put by one member of an extremist group, thirty people planning such an operation could be called an underground; three hundred, a movement; and three thousand, a revolution.534 The next year an Israeli court sentenced twenty-seven Underground members for the attempt on the Mount and their other terrorist attacks to prison terms ranging from a few years to life. By 1990, though, pressure from Israeli right-wing groups saw all of them freed.535

Almost until his death in 1994, Rabbi Goren continued to cause trouble. On his infamous first visit to the Mount, he began to measure and survey it. A few years before his demise, he published those measurements along with a scriptural commentary that declared that a large southern strip of the Mount lay outside the Temple’s sacred confines, and so was suitable for building a synagogue. The article ignored the fact that the site is currently occupied by the al-Aqsa Mosque.

Archaeology under the Mount incites the same Arab anger as prayer on its surface. Despite overwhelming historical and archaeological evidence, Muslims generally deny the existence of both the First and Second Temples and consider any excavation of the layers under the Mount’s surface as a Jewish attempt to justify building a third one.

Over the centuries, human settlements accumulate successive layers of sediment, so the deeper an archaeologist digs, the further back she travels in time. Vivid demonstrations of this are occasionally visible in cities with ancient histories such as Rome and Jerusalem, where excavations dating to the time of Christ are seen one or two dozen feet below the modern streets.

In Jerusalem, this means that an archaeologist first encounters artifacts from the Ottoman period, followed by those of successively earlier Muslim kingdoms, then Roman, Greek, Jewish, and, if very lucky, the Canaanite rulers. After the 1967 conquest, for the first time Jewish researchers, led by Hebrew University archaeologist Benjamin Mazar, gained access to the area surrounding the Mount.

Mazar’s most significant discovery was from the period of the late Second Temple of Herod, which uncovered a large public area with extensive housing, broad streets, and a sophisticated water system adjacent to the Mount, as well as monumental steps leading up to it, as close to dispositive proof of the Second Temple as an archaeologist might find.

The Waqf complained to UNESCO that the excavations undermined the stability of the Mount, and the U.N. organization appointed a series of independent investigators who found no evidence of structural compromise and praised the archaeological results, though one participant did criticize the fact that the excavations had been performed without the permission of the Arab landowners.536

Far more serious problems resulted from the Western Wall Tunnel, which runs underground along the entire western edge of the Mount. Begun in 1969 by the Israelis, its excavation destroyed multiple structures from the Mamluk period and greatly upset the Waqf; the digging resulted in denouncements in the U.N. General Assembly and subsequent U.N. sanctions. In protest against the U.N. sanctions, the United States and some of its allies stopped their contributions to UNESCO, which nearly bankrupted it.

The nineteenth-century English archaeologist Charles Warren had extensively excavated on and under the Mount, and one of his many discoveries was an ancient gate under the Western Wall that opened into a tunnel under the Mount, and thence to a staircase to its surface near the Dome of the Rock. Warren later wrote The Land of Promise, a pamphlet that suggested that a European consortium, “similar to the old East India Company,” colonize Palestine with Jews.537

In 1981, workers in the Western Wall Tunnel under the direction of Rabbi Yehuda Getz re-encountered “Warren’s Gate” and the eastbound tunnel beyond, which Getz believed led to the Holy of Holies and perhaps even to the lost Ark of the Covenant. His team began to excavate eastward under the Mount itself toward the Dome, apparently with the cooperation of the Israeli Religious Affairs Ministry. Several weeks after Getz’s discovery, Waqf guards heard noise coming from the excavation below and descended through the cisterns, where they battled with the Jewish archaeologists.538

True to form, Goren proclaimed the new tunnel even holier than the Western Wall. Arabs, on the other hand, saw a naked attempt to gain control of the Mount, and the Israelis, faced with intense Arab hostility, sealed off the tunnel with a thick concrete wall, placing it off limits, possibly forever, to further investigation.

Shortly after the Western Wall Tunnel’s completion in the mid-1980s, the Israelis opened it to tourists. Because of the passageway’s narrowness, visitors had to double back to exit from its southern entrance near the Wailing Wall; the resulting congestion seriously limited traffic. To remedy this problem, the Israelis built an exit at its northern terminus, which again inflamed the Arab populace, who saw the new portal as an attempt to undermine and collapse the Mount; angry crowds gathered, and work was temporarily halted.

At midnight on September 23, 1996, the Israelis cracked open the street over the northern portal and quickly placed an iron door there. Two days later riots broke out all over the Palestinian territories that featured a pitched battle between the Israeli army and the Palestinian National Security Force, newly created under the Oslo Accords; dozens were killed on both sides, and hundreds were injured.539 The situation became fraught enough for President Clinton to call an international summit, which proved inconclusive. Subsequently, the unrest died down and the exit remained open; today, tourists who exit the tunnel are surprised to find themselves greeted by Israeli guards who escort them back to the Wailing Wall.

Israel’s 1967 conquest of the Old City and West Bank would change not only the political complexion of the Middle East and of Arab-Israeli relations, but it would also increasingly impinge upon politics, religion, and culture in both the United States and Israel. It would do so in ways that the direct combatants in that year’s events could hardly have predicted. Most alarmingly, its American dispensationalist protagonists would be driven by a belief system so delusional and divorced from real-world facts as to make John Nelson Darby blush.

492. Tom Segev, One Palestine, Complete, trans. Hiam Watzman (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 1999), 430.

493. Granted in 1920, the Mandate did not formally take effect until 1923.

494. Moshe Dayan, Story of My Life (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1976), 45.

495. Yoon, 233.

496. André Gerolymatos, Castles Made of Sand (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2010), 71–77.

497. Ralph Sanders, “Orde Wingate: Famed Teacher of the Israeli Military,” Israel: Yishuv History (Midstream—Summer 2010): 12–14.

498. Anonymous, “Recent Views of the Palestine Conflict,” Journal of Palestine Studies Vol. 10, No. 3 (Spring, 1981): 175.

499. Lester Velie, Countdown in the Holy Land (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1969), 105.

500. Simon Anglim, Orde Wingate and the British Army, 1922–1944 (London: Routledge, 2010), 58.

501. Yoel Cohen, “The Political Role of the Israeli Chief Rabbinate in the Temple Mount Question,” Jewish Political Studies Review Vol. 11, No. 1 (Spring 1999): 101–105.

502. For the full range of theological discussion on the matter, see, on the pro-rebuilding side, Jerry M. Hullinger, “The Problem of Animal Sacrifices in Ezekiel 40–48,” Bibliotheca Sacra Vol. 152 (July–September, 1995): 279–289; and on the anti-rebuilding side, Philip A.F. Church, “Dispensational Christian Zionism: A Strange but Acceptable Aberration of Deviant Heresy?,” Westminster Theological Journal Vol. 71 (2009): 375–398.

503. Chaim Herzog, The Arab-Israeli Wars (New York: Random House, 1982), 54–55.

504. Paul Charles Merkley, Christian Attitudes Towards the State of Israel (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001), 140.

505. Hertzel Fishman, American Protestantism and a Jewish State (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1973), 23–24, 83. For oil company opposition to Israel’s establishment, see Zohar Segev, “Struggle for Cooperation and Integration: American Zionists and Arab Oil, 1940s,” Middle Eastern Studies Vol. 42, No. 5 (September 2006): 819–830.

506. Quoted in ibid., 29.

507. Quoted in ibid., 34.

508. Ibid., 53–54.

509. Reinhold Niebuhr, Love and Justice (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1992), 139–141. (Note: the section quoted is reprinted from “Jews After the War,” published in 1942.)

510. Ibid., 141.

511. Yoon, 354–365, quote 362.

512. Samuel W. Rushay, Jr., “Harry Truman’s History Lessons,” Prologue Magazine Vol. 41, No. 1 (Spring 2009): https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2009/spring/truman-history.html, accessed January 8, 2018.

513. Merkley, The Politics of Christian Zionism (London: Frank Cass, 1998), 187–189, quotes 188.

514. Paul Charles Merkley, American Presidents, Religion, and Israel (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2004), 4–5.

515. Merkley, The Politics of Christian Zionism, 191.

516. Yoon, 391, 395; and Thomas W. Ennis, “E. Schuyler English, Biblical Scholar, 81” The New York Times, March 18, 1981.

517. Shabtai Teveth, Moshe Dayan, The Soldier, the Man, and the Legend, trans. Leah and David Zinder (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1973), 335–336.

518. Dayan, 31, 128–131.

519. Herzog, 156–206; Dayan, 366; and Ron E. Hassner, War on Sacred Grounds (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009), 117.

520. Of historical note, the ruined state of Athens’ Parthenon is largely due to the detonation of an Ottoman munitions dump during the Venetian siege of 1687.

521. Cohen, 120 n3.

522. Dayan, 386.

523. Ibid., 387.

524. Ibid., 388.

525. Gorenberg, 98.

526. Ibid., 387–390; and Rivka Gonen, Contested Holiness (Jersey City, KTAV Publishing House, 2003), 153.

527. Gonen, 157; Gorenberg, 107–110; and Abraham Rabinovich, “The Man Who Torched al-Aqsa Mosque,” Jerusalem Post, September 4, 2014.

528. See, for example, Ronald Siddle et al., “Religious delusions in patients admitted to hospital with schizophrenia,” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology Vol. 37, No. 3 (2002): 130–138.

529. Gershom Scholem, Sabbatai Sevi (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973), 125–142, 461–602, 672–820.

530. For a masterful history of assassination as an instrument of Israeli/Jewish policy, both before and after independence, see Ronen Bergman, Rise and Kill First (New York: Random House, 2018), especially 18–30 for those involving Irgun and Lehi. For the eighteen points, see http://www.saveisrael.com/stern/saveisraelstern.htm.

531. Lawrence Wright, “Forcing the End,” The New Yorker, July 20, 1998, 52.

532. The Mount has eighteen gates; six are sealed, and one is physically open but prohibited for public use. Muslims can use the remaining eleven, but non-Muslims can enter by only one, the Mughrabi Gate at the southwest corner, next to the Western Wall.

533. Eight years later, Kahane was assassinated in Brooklyn by El Sayyid Nosair, an American citizen who had been born in Egypt and trained in Pakistan by an organization founded by Osama bin Laden.

534. Gonen, 158–159.

535. Jerold S. Auerbach, Hebron Jews (Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2009), 114–116; and Nur Mashala, Imperial Israel (London: Pluto Press, 2000), 123–126.

536. Gonen, 161–162.

537. Charles Warren, The Land of Promise (London: George Bell & Sons, 1875), 4–6.

538. Nadav Shragai, “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” Haaretz, April 25, 2003.

539. Serge Schmemann, “50 Are Killed as Clashes Widen from West Bank to Gaza Strip,” The New York Times, September 17, 1996.