Hucksters of the Digital Age

We don’t get up every morning thinking business is bad.

—Roger Ailes771

The reason many chose to ignore the obvious signs of a bubble, and particularly the Enron accounting garbage pile, can be summed up in two words: “investment banker.” Over the past few decades, that job description has become shorthand for “someone who makes an obscene amount of money.” When an investment bank floats an IPO, it earns a commission of 5 to 7 percent of the proceeds. Netscape yielded fees of $130 million, and Webvan, $375 million; later IPOs would earn the banks billions. Individual employees garnered a large slice of this pie. When Frank Quattrone moved from Morgan Stanley to Credit Suisse in 1998, his next year’s personal share of this bonanza rose to approximately $100 million.772

One of the more bizarre features of the dot-com era was the rise to celebrity status of the once lowly stock analyst, who before the 1990s toiled away in modestly well-compensated anonymity in the bowels of investment companies. The dot-com bubble propelled a handful of them to a visibility usually reserved for superstar athletes and movie actors, as an eager public followed their every pronouncement about the prospects of this or that dot-com. The two most famous were Morgan Stanley’s Mary Meeker and Merrill Lynch’s Henry Blodget. The problem was that the same companies that cranked out the stocks and bonds also employed the folks who “analyzed” the stocks and bonds.

The financial industry is the eight-hundred-pound gorilla of the U.S. economy, representing nearly one-fifth of both GDP and the value of stock market shares. Because investment banking represents the biggest source of this bounty, analysts who didn’t play along with a steady stream of “buy” recommendations could be pressured, as John Olson, who covered Enron for Merrill Lynch, learned.

Enron executives obsessively followed the company’s stock price, especially Fastow, whose schemes depended on it, and their major investment banking interest lay in the bond offerings that fueled their breakneck global expansion. These offerings generated enormous fees for the investment banks, a fact about which Enron never ceased to remind its banks. One analyst reported being told by the company, “We do over $100 million of investment-banking business a year. You get some if you have a strong buy [recommendation to clients].”773

Unhappily for Olson, he didn’t follow that playbook. Unlike James Chanos, who suspected fraud, Olson wasn’t overly negative about Enron, reporting that he simply didn’t understand its accounting and noting in one media interview, “They’re not very forthcoming about how they make their money. . . . I don’t know an analyst worth his salt who can seriously analyze Enron.”774 Enron chairman Lay despised Olson and wrote a note to his boss at Merrill Lynch, Donald Sanders: “Don, John Olson has been wrong about Enron for over ten years and is still wrong, but he is consistant [sic].” (When Sanders showed Olson the note, he observed that he might be old and worthless, but at least he knew how to spell “consistent.”)775 Eventually, a pair of Merrill Lynch investment bankers complained to the company’s president, Herbert Allison, who apologized to Lay. Merrill Lynch let Olson go and kept its seat on the Enron gravy train.776

During the 1990s, different versions of the Merrill/Enron/Olson drama were played out by thousands of actors on hundreds of stages, and while every script was different, the plotline remained constant, as stock analysts abandoned their craft and became cheerleaders for their investment banking colleagues. One researcher compiled more than fifteen thousand stock reports from just one year, 1997; fewer than 0.5 percent recommended selling shares.777

Along with the promoters, the investing public forms the second anatomic locus of financial manias. In the years preceding the internet bubble, more and more Americans had become their own investment managers, and while increasing incomes and wealth largely drove this phenomenon, something else was happening as well: They had to.

In the decades following the 1929 crash, the U.S. economy and social structure had undergone profound changes, prime among which was the gradual lengthening of life expectances, and with it, the extension of retirement. When Otto von Bismarck established the concept of old-age pensions in Germany in 1889, the median life expectancy of European adults was forty-five, decades below the seventy-year qualifying age, and in any case, families generally took care of their elderly members. By the end of the twentieth century, Americans contemplated retirements lasting more than three decades, and increasing geographical mobility often made direct family care impossible. All these factors increased the onus on individuals to fund their ever-more expensive golden years.

The luckiest American workers spent their careers at large companies that provided so-called defined benefit plans that supplied a pension until the employees, and usually their spouses, died (assuming the company did not fire them just before they qualified for a pension, an all-too-common practice). Studebaker, an automobile manufacturer, was one such benevolent employer, but when it closed its last U.S. plant in 1963, it set in motion a series of congressional investigations that eventually gave rise to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) in 1974, which governs pension operations to this day. One of the act’s more obscure sections established Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), which allowed workers for the first time to accumulate savings free of income tax until withdrawal in retirement; in 1981, the government loosened initial restrictions on their use, making them more attractive to employers and available to more workers.

At roughly the same time, a pension benefits consultant named Ted Benna was growing increasingly dissatisfied with his work, which primarily involved answering the following question for employers: “How can I get the biggest tax break, and give the least to my employees, legally?”778 This troubled the devout and generous Benna, who sought a way to get companies to do right by their workers.

Benna noticed that the Revenue Act of 1978 had added an obscure subsection to the IRS Code, § 401(k), which allowed employers to directly defer their employees’ salaries into retirement savings. Benna imagined the number of workers doing so would increase if employers could induce them by offering to match their contributions. Benna had connections at the IRS, which approved the scheme. His invention mushroomed; today, the trillions of dollars in 401(k) assets roughly match those in IRAs.779

These individual accounts consequently allowed companies to abandon their commitment to traditional defined-benefit pension plans; along with the loosening of intergenerational bonds brought about by increased geographical mobility, workers and small businessmen suddenly became their own pension managers, a job that requires a combination of quantitative skills, historical knowledge, and emotional discipline that few finance professionals, let alone lay people, possess.

The inability of ordinary investors to competently invest is evident, for example, in data on the performance of mutual funds that are now by far the most common retirement vehicles; they are essentially the only choices available in defined-contribution retirement schemes such as company 401(k) plans. Were investors competent, their “internal rate of return” (IRR, which accounts for all fund shares bought and sold) on these vehicles should exactly equal the underlying return of the fund. Sadly, researchers have found that, on average, employees time their fund purchases and sales so poorly that the IRR they earn on them is almost always lower than the return of the funds themselves.780 In other words, more often than not, small investors buy high and sell low, robbing themselves of the full market return available from a given fund.

CNBC epitomized the third anatomic location of bubble anatomy, the press, during the dot-com era. Its predecessor in television business and investment information, the Financial News Network, began operations at the wrong time, in 1981, toward the tail end of a long, brutal bear market that marked a nadir in public interest in investing; a decade later, it went bankrupt. In 1989, NBC, eager to improve its anemic ratings and sensing renewed public interest in investing, founded the Commercial News and Business Channel.

NBC’s timing could hardly have been better, for the markets had begun to turn around, and tens of millions of people, as much out of necessity as out of interest, began to follow stocks. Initially, its programming was soporific: anchors faced the cameras from behind card tables and presented shows on dinner preparation and managing children’s tantrums.781 In 1991, its fortunes improved a little, as the bankrupt remains of FNN fell into its hands, along with much of its talent, and it shortened the channel’s name to its acronym, CNBC.

In 1993, the media gods smiled even more broadly on the fledgling network with the arrival of Roger Ailes, then at the apex of his legendary grasp and deployment of television’s raw emotive power. Born with hemophilia and saddled with a father fond of corporal punishment—a particularly unfortunate combination—his frequent bleeding episodes resulted in long periods of confinement at home, where his real classroom became 1950s television, which he spent endless hours analyzing. Unsurprisingly, he majored in media studies, and after college graduation cut his teeth on production work at local east coast television stations.782 Ailes then hired on with the nationally syndicated Mike Douglas Show as a prop boy; within three years he became its producer. Shortly after that promotion, in 1968, he encountered Richard Nixon, then pursuing his second presidential bid, in the show’s studio. Nixon expressed distaste that “a man has to use gimmicks [like television] to get elected,” to which Ailes replied, “Television is not a gimmick.” Shortly after that encounter, Nixon aide Leonard Garment hired him.783 Thus did Ailes begin a quarter-century career in media consulting for Republican presidents, making Nixon more likable in 1968 and in 1988 helping George H. W. Bush defeat Michael Dukakis.

Upon becoming president of CNBC, Ailes kept what had worked from the old FNN format, particularly the ubiquitous stock ticker “crawl” running at the bottom of the screen, which would become the metaphorical background soundtrack of the financial bubble’s soap opera. Otherwise, he overhauled every aspect of the look and feel of the network, and later applied the same techniques to his new charges that had worked so well with national politicians and business giants. Instead of simply announcing a new segment with theme music, he added voiceovers with tight head shots of the anchors. Recipes and child temper tantrums were out; Geraldo Rivera and the engaging political commentator Mary Matalin were in. Ailes personally instructed camera operators on how to properly frame corporate executives to make them appear more alive, prodded writers to come up with more compelling “don’t touch that dial” patter, and sent anchors to breathlessly report the price action from the stock exchange floor. The more flamboyant the guest, the better. As put by the New Yorker’s John Cassidy,

Their ideal studio guest was a former beauty queen who covered technology stocks, spoke in short declarative sentences, and dated Donald Trump. Since there weren’t many of these women available, the producers generally had to settle for balding, middle-aged men who revered Alan Greenspan and tried their best to speak English.784

Ailes taught his anchors and production staff to treat finance as a spectator sport; after one particularly brutal week in the market, one of his advertising clips caustically compared the new network to its archrival: “The Dow plummets in heavy trading. But first, today’s weather. CNN tells you if your shirt will get wet; CNBC tells you if you’ve still got one.” He also married sex and finance by promoting a new recruit from CNN, Maria Bartiromo, into an anchor position; with her Sophia Loren looks, dense Brooklyn accent, and blatant sex appeal, she quickly became known as “the Money Honey.”785

In 1996, CNBC forced Ailes out for the bullying behavior that would haunt his later career, but by then his media makeover had proven hugely profitable. By the mid-1990s, CNBC had opened sister networks in Europe and Asia, and the sun never set on the constant drama, real or manufactured, of the world’s capital markets.

Ailes intuitively understood that his audiences preferred the cotton candy of entertainment to the spinach of information and analysis; and best of all was a confection that spun unlimited wealth. Under Ailes, CNBC mastered that genre and perpetrated a feat of modern cultural alchemy by transmuting the tedious world of mainstream finance into wildly successful entertainment. The new venue’s attention centered on the internet, which small investors could use to instantaneously act on what they had just viewed on CNBC through online brokerages such as E-Trade and Datek, the latter favored by day traders.

Investigative reporting went out the window; it cost gobs of money, and worse, it offended the all-important investment banks, whose parent companies purchased the lion’s share of the advertising. Better to fill broadcast time slots with interviews of corporate executives who talked enthusiastically about their companies, and “market strategists” who spoke authoritatively about where stocks were headed. Best of all, the executives and strategists appeared for free and arrived in hired cars from across the Hudson to CNBC’s studios in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

CNBC’s offerings lacked any critical examination of the uniformly optimistic pronouncements of both its corporate executive and most brokerage analyst guests. In 2000 and 2001, CNBC anchor Mark Haines interviewed, respectively, Ken Lay and Jeffrey Skilling. Haines had graduated from the University of Pennsylvania’s law school and fancied himself a sharp inquisitor, but when faced with the perpetrators of one of history’s greatest corporate frauds, he exuded only a wide stream of praise and puff questions.786

When major corporations like IBM, Sears, and AT&T laid off tens of thousands of employees, CNBC cheered the company’s buoyed bottom line, oblivious to the human cost of mass firings. When corporations committed apparent felonies, CNBC simply looked the other way, at least as long as the resulting scandal stayed off newspapers’ front pages, as when the network brushed off reports in May 2012 that J. P. Morgan had hid $2 billion of trading losses from its shareholders.787

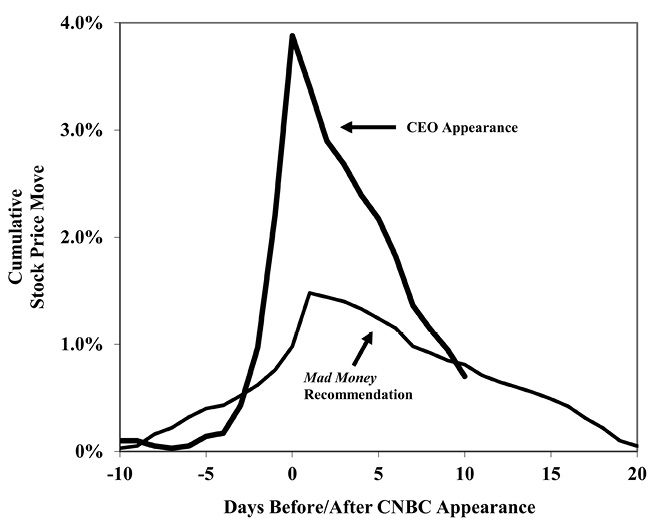

Figure 14-1. CNBC and Stock Prices

Nor did the network do much good for viewers’ bottom lines. Two representative academic studies looked closely at the value of acting on the show’s guest list and recommendations; their conclusions were not encouraging. The first examined the reaction of stock price to the appearance of corporate CEOs on CNBC, and the second researched the performance of the stock picks of one of the network’s most popular current programs, Mad Money, hosted by the frenetic, boisterous James Cramer. The results of both studies, shown in figure 14-1, are nearly identical: A price bump, relative to the rest of the stock market, peaked on the day of, or day after, the show, then fell. As alarming as the postshow price fall was, the rise beforehand suggested that participants with foreknowledge of the show’s schedule of guests played CNBC’s viewers like two-dollar banjos. Despite his clownish appearance, Cramer was no dummy, and well understood this dynamic. On at least one occasion he had sold stock in a company touted on Bartiromo’s show, then bought it back a few days later after its price drifted back down.788

Even more telling were those CEOs who elected not to participate in the circus. Jeff Bezos, the chairman and founder of the period’s most successful IPO, Amazon, enjoyed intellectual back-and-forth with informed journalists and often granted interviews to even minor publications. He saw little point, though, in appearing on CNBC, which he knew would focus on the short-term outlook for the company’s stock price, and which he considered a worthless distraction. If he took care of his customers, he felt, the company would prosper in the long run, no matter how the stock price wandered along the way.789

The fourth locus of bubble anatomy centers on political leaders. During the Mississippi, South Sea, and railway bubbles, leaders at the highest levels had thrust their hands deeply into the cookie jar, including the monarchs of France and Britain. Starting in the late nineteenth century, because of increased public scrutiny and antigraft legislation, politicians figured less often as prominent speculators: During the 1920s, direct political involvement in bubble propagation reached little higher than John Raskob, the Democratic Party National Committee chairman.

During the 1990s, the prospect of tens of millions of 401(k) participants and IRA owners, each his or her own little capitalist, enthralled conservatives; influenced by the theories of Ayn Rand, Milton Friedman, and Friedrich von Hayek, they gloried in the new “ownership society.” While the 1990s tech bubble did not involve significant political acts of commission—that is, outright graft and corruption—political acts of omission took center stage, namely inattention to the regulatory safeguards that were put in place during the 1930s in the wake of the Pecora Commission; by the 1980s the Glass-Steagall Act’s strict separation of commercial and investment banking operations had been rendered toothless from inattention long before its final repeal in 1999.

CNBC’s coverage and tone gloried in the ideological underpinnings of the great bull market. In what amounted to the opening prayer of its “Kudlow Report” segment, its host Lawrence Kudlow would intone, “Remember, folks, free market capitalism is the best path to prosperity!”790 Conservative journalist James Glassman, perhaps more than anyone else, cemented the connection between the tech bubble and free-market ideology. Best known as the author of multiple investing books, he was, and remains, a favorite on conservative venues, especially The Wall Street Journal. In the 1990s he rhapsodized about how the market’s meteoric rise was a mere prelude to what was to follow from free-market capitalism’s cornucopia. So when stocks began to crumble in April 2000, he blamed Uncle Sam for stifling those markets. Reacting to a ruling favorable to the government’s antitrust suit against Microsoft, he observed:

No one ever knows for sure why a stock falls on a given day, but my interpretation of Nasdaq’s sharp decline is that investors, jarred by the Microsoft decision, have suddenly woken up to these threats of government intervention. If they haven’t woken up, they had better. And so should [Vice President and presidential candidate] Al Gore. The Clinton administration likes to take credit for a stock market that has quadrupled in the past decade. It can’t avoid the blame for Nasdaq’s collapse.791

George Gilder, a former speechwriter for Richard Nixon and Nelson Rockefeller, to whom the connection between the great 1990s bull market and the superiority of unfettered free markets was an article of faith, provided the most extreme example of 1990s tech enthusiasm. In a remarkable editorial in The Wall Street Journal published on the portentous date of January 1, 2000, Gilder posited that the internet didn’t merely change everything, but transformed the very “space-time grid of the global economy.” He deployed grandiose metaphors that invoked the vastness of the empty reaches inside the atom, the “manipulation of the inner structure of matter,” and even slipped quantum mechanics and “centrifical [sic] force” past the Journal’s editors, concluding that only through the bounteous application of faith, love, and religious commitment would mankind triumph in the brave new digital age.792 High above at the Pearly Gates, the editors of the Railway Times applauded.

How did Gilder, Kudlow, and Glassman, all of whom possessed formidable intellectual horsepower burnished with Ivy League educations, get things so spectacularly wrong in the late 1990s? Starting in the twentieth century, psychologists began to realize that people use their analytical ability not to analyze, but rather to rationalize—that is, to conform observed facts to their preconceived biases. (Economists have long observed that “if you torture the data long enough, it will eventually confess.”) Understanding the two main reasons why humans do so lies at the heart of both individual and mass delusions.

The first reason for the proclivity all of us—the smart, the dumb, and the average—have for such irrationality is that true rationality is extraordinarily hard work, and few possess the ability to do it. Further, the facility for rationality correlates imperfectly with IQ. In the early 2000s, an academic named Shane Frederick, who had acquired a doctoral degree in the relatively new discipline of decision sciences, invented a famous paradigm that demonstrates just how difficult pure analytical rigor is.

Not long after earning his doctorate, Frederick wrote a classic paper describing a simple questionnaire. Known among psychologists as the cognitive resource test (CRT), it measured the quotient of rational ability—call it RQ—as opposed to IQ. It consisted of only three puzzlers, the most famous of which (at least in economic circles) is this one: Suppose that a baseball and a baseball bat together cost $1.10, and that the bat costs a dollar more than the baseball. How much does the ball cost? Most people, even highly intelligent ones, will quickly answer $0.10. But this cannot be, since it means that the bat costs $1.10, and so makes the total price $1.20. Rather, the ball must cost $0.05, which makes the bat $1.05, and the total cost of both the desired $1.10.793

If you found the baseball/bat question and the two others in the footnote easy, you might find another puzzler, half a century old, a little more challenging. Wason’s Four Card test involves cards with a letter on one side and a number on the other. Start with this rule: “If a card has a vowel on its letter side, it has an even number on its number side.” Four cards are showing: K, A, 8, and 5. Which two cards do you turn over to prove or disprove the rule?

The overwhelming majority of subjects will intuitively answer A and 8, but the correct answer is A and 5. With typical academic understatement, Wason, who pioneered the concept of confirmation bias, wrote, “The task proved to be peculiarly difficult.” To answer correctly, one first has to realize that the rule, when carefully considered, allows that cards with even numbers can have both vowels and consonants on the other side, so it does no good to turn over the 8 card. To disprove the conjecture, one must turn over the 5; if it has a vowel, then the conjecture is false, as will also be true in the easier case of turning over the A and finding an odd number.794

Rational thought takes considerable effort, and almost all human beings are mentally lazy or “cognitive misers,” in psych-speak, and they intuitively seek analytical shortcuts like the heuristics described by Kahneman and Tversky. The intense cognitive effort demanded by rigorous rationality is not at all pleasant, and most people avoid it. As put by one academic, we “engage the brain only when all else fails—and usually not even then.”795

IQ and RQ thus measure different things. While IQ measures the ability to handle abstract verbal and quantitative mechanics, particularly algorithms, RQ focuses instead on what comes before those algorithms are applied: Before analyzing the facts, does the subject carefully lay out the problem’s logic and consider alternative analytical approaches? And after arriving at an answer, does she consider that her conclusions may be wrong, estimate that probability, and calculate the consequences of such an error? A high IQ, it turns out, provides little protection against these pitfalls. In the droll assessment of Keith Stanovich, the inventor of an expanded RQ-measuring battery, the Comprehensive Assessment of Rational Thinking (CART), “Rationality and intelligence often dissociate.”796

The second main reason for our propensity to act irrationally is that we more often than not apply our intellects to rationalization, and not to rationality. What we rationalize, generally speaking, are our moral and emotional frameworks, as evidenced by the division of our cognitive processes into a fast-moving System 1, seated in our deeply placed limbic systems—our “reptilian brains”—and a plodding System 2 that analyzes the rationality-demanding tasks of the CRT and CART.

For most of humanity’s history, our two-system apparatus served us well. In the words of psychologist R. B. Zajonc, “It was a wise designer who provided separately for each of these processes instead of presenting us with a multiple-purpose appliance that, like the rotisserie-broiler-oven-toaster, performs none of its functions well.”797

In the postindustrial world, whose planning horizon, particularly for financial affairs, stretches decades into the future, the decisions we face look less and less like the second-to-second System 1 functioning that decided the survival of our ancestors on the African savannahs and more and more like the mind-twisting System 2 questions in the CRT and CART, a problem compounded by the fact that, more often than not, we use our System 2 to rationalize the conclusions already reached by our emotionally driven System 1. In other words, the vaunted human System 2 functions mainly as, in the words of Daniel Kahneman, System 1’s “press secretary.”798

Because of this greater need for cognitive effort, even the best and brightest prove inadequate to the forecasting and decision-making societal tasks facing us. By the 1970s, Kahneman, Tversky, and others sensed that human beings were terrible at forecasting, but not until more recently have researchers begun to measure just how terrible we are.

Beginning in the late 1980s, psychologist Philip Tetlock began to quantify the predictive abilities of supposed authorities in their fields by examining the performance of twenty-eight thousand predictions made by 284 experts in politics, economics, and domestic and strategic studies. First and foremost, he found that experts forecast poorly—so poorly that they lagged simple statistical rules that fed off the frequencies of past events: the “base rate.”

For example, if the average investing “expert” is asked about the likelihood of a market crash in the coming year, defined as a fall in price by more than, say, 20 percent, he will likely spin a narrative about how Fed policy, industrial output, debt levels, and so forth affect that possibility. What Tetlock discovered was that it was best to ignore this sort of narrative reasoning and simply look at the historical frequency of such price falls. For example, monthly stock market price falls of more than 20 percent have occurred in 3 percent of the years since 1926, and this simple data point proves more accurate in forecasting the likelihood of a crash than narrative-based “expert” analysis.

Tetlock also found that certain experts did especially badly. His research broadly separated them into two categories, as described in a famous essay by social and political theorist Isaiah Berlin entitled “The Hedgehog and the Fox.”799 In Tetlock’s taxonomy, the hedgehog is an ideologue who interprets everything he sees according to an overarching unitary theory of the world, whereas the fox entertains many competing explanations. Foxes tolerate ambiguity better than hedgehogs and feel less compelled to come to firm conclusions. Hedgehogs possess greater confidence in their predictions and make more extreme ones; critically, they change their opinions less frequently than do foxes when presented with contrary data, a behavior that corrodes forecasting accuracy.

Analysis-killing hedgehoggery infects the political right and left equally: For example, radical environmentalists to this day defend Paul Ehrlich’s famously off-base 1970s predictions of imminent global starvation and natural resource shortages, and libertarians do the same for influential economist Martin Feldstein’s high-profile warning that Bill Clinton’s budgets and social policies would wreck the economy.

Ever since our prehistoric ancestors began consulting shamans, people have sought certainty in an uncertain world by consulting experts. Tetlock tested the forecasting ability of three broad groups: undergraduates, recognized authorities in the area of a given forecasting question, and “dilettantes” who were knowledgeable in one field but were forecasting outside it. Not surprisingly, the undergraduates performed the worst. More remarkably, the experts performed no better than the dilettantes; further, when Tetlock then broke down these results between foxes and hedgehogs, specialty expertise in the area in question seemed to benefit the forecasts of the foxes but worsened those of the hedgehogs.

In other words, a foxy environmental scientist will likely better forecast a military outcome than a hedgehoggy military specialist, and vice versa. The reason for this seems to be that while the experts and dilettantes both tended to overestimate the probabilities of extreme outcomes, the experts did so more of the time, and paid the price in forecasting accuracy attendant to extreme predictions. The dilettantes, it would seem, behaved more like foxes, at least outside their field of expertise. The sweet spot of knowledge would thus appear to be, in Tetlock’s words, “in the vicinity of savvy readers of high-quality news sources such as the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the New York Times, the publications that dilettantes most frequently reported as useful sources of information on topics outside their specialties.”800

This somewhat startling statement stems from Tetlock’s finding that experts generally use their knowledge to rationalize how the data conform to their preexisting worldview. Since hedgehogs hold on to their preexisting views more tightly, they rationalize their errors more reliably. For example, Tetlock found that “loquacity,” the ability to enumerate a large number of arguments in support of a prediction, was a marker for poor forecasting. Tetlock suggests a simple rule of thumb for identifying an expert’s animal mascot: hedgehogs use the word “moreover” more than “however,” whereas foxes do the opposite.801

Most of us suffer from strong bias toward self-affirmation, the desire to think well of ourselves, and thus misremember our forecasts as more accurate than they actually were; conversely, we erroneously remember our opponents’ forecasts as less accurate. Hedgehogs, though, have an especially marked tendency to do this, and Tetlock enumerated the most notable excuses they deploy: “A bolt out of the blue derailed my prediction,” “I was almost right,” “I wasn’t wrong, I was just early,” and finally, when all else fails, “I haven’t been proven right yet.” He succinctly summarized this tendency: “It is hard to ask someone why they got it wrong when they think they got it right.”802

Finally, Tetlock identified a particularly potent forecasting kiss of death: media fame. For its part, the media seeks out “boomsters and doomsters”; that is hedgehogs fond of extreme predictions, who appeal to viewers more favorably than do equivocating foxes. Further, media attention produces overconfidence, which itself corrodes forecasting accuracy. The result is a media-forecasting death spiral that seeks extreme, and hence poor, forecasters, whose media exposure then worsens their predictions. Tetlock observed, “The three principals—authoritative-sounding experts, the ratings-conscious media, and the attentive public—may thus be locked in a symbiotic triangle.”803 In retrospect, Kudlow, Gilder, and Glassman, the tech bubble’s ideological cheerleaders, had hit the Tetlock trifecta: media-darling hedgehogs fond of extreme predictions.

The dot-com era exhibited all of the classic signs and symptoms of a financial bubble: the dominance of stock investing in everyday conversation, the abandonment of secure jobs for full-time speculation, the scorn and ridicule heaped on skeptics by true believers, and the prevalence of extreme predictions.

Never before had extreme market ebullience and the subsequent disaster been so closely observed and recorded in real time on TV screens and, increasingly, on the internet itself. The ebullience infected venues in the tech industry’s pampered nerve centers in Silicon Valley, on Wall Street, and in CNBC’s studios in Fort Lee, but the market fever that gripped everyday conversation was most acutely felt on Main Street, in social gatherings and investment clubs.

A poignant ground-level narrative of this obsession played out in that bastion of working-class male solidarity, a barber shop, on Massachusetts’s Cape Cod. In normal times, the talk in such places runs mainly to sports and politics, and if the establishment is graced with a television set, it is tuned to a baseball, football, or basketball game. But the turn of the last century was no normal time, and Bill’s Barber Shop in Dennis, Massachusetts, owned and operated by Bill Flynn, was no ordinary haircutting establishment.

By 2000, Flynn had been cutting hair for a third of a century and was no stranger to the stock market. His great-grandfather, also a barber, had offered him superb advice: save 10 percent of his earnings and put it into equities. Bill’s execution of that wisdom proved less than stellar, for he was driven by the human phenomenon exploited so well by South Sea’s John Blunt, the preference for lottery-like outcomes. In the mid-1980s, Cabbage Patch Dolls were all the rage, and large numbers of children and adults “invested” in them, never mind the fact that they could be manufactured at will. At the height of the frenzy, Flynn bought shares on margin—that is, with borrowed money—in Coleco, Inc., the company that made them.

The company’s 1988 bankruptcy decimated his original savings, but he stoically soldiered on and continued to put his spare earnings into the market. Over the course of a decade, he socked away $100,000 into the most glamorous high-tech names he could find: AOL, Yahoo!, and Amazon, among others. By 2000, his nest egg had grown to $600,000. Bill had told himself that he would retire when his portfolio hit two commas; given how well he was doing, he figured, he would be there shortly.804

If manias resemble epidemics, “the internet changes everything and it’s going to make us all rich” narrative was the virus, and Bill Flynn was Cape Cod’s Patient Zero. By 2000, the patter around the barber chair had switched from the Red Sox, Celtics, and Patriots to EMC and Abgenix, Bill’s two favorite stocks. The TV was tuned to CNBC.

The toxic combination of round-the-clock financial entertainment and instantaneous online trading played out tragically in Bill’s shop. He spun compelling narratives and cajoled his small-business-owner customers into purchasing the shares of his chosen companies.805 When Wall Street Journal reporter Susan Pulliam first visited the shop in the winter of 2000, just as the market was peaking, the talk was all tech stocks, all the time. Bill suggested Abgenix, a biotech firm, to one customer. Others in the shop variously volunteered that they had purchased Coyote Technologies, had owned Network Appliance, or, if less adventurous, were merely considering a mutual fund offered by Janus, an investment company that specialized in tech-oriented portfolios.

Bill’s favorite was a data storage firm, EMC: “I’d say I’ve put 100 people into EMC.” None of them seemed to care that Bill had settled on the company not through rigorous security analysis, but rather via a tip from another barber. By mid-2000, stocks had encountered several severe downdrafts, but Bill and his customers were confident of their staying power. As put by one, a painter/wallpaperer, “Even if we do go down 30 percent, we’ll come right back.” Weaker souls drew ridicule. Flynn pointed out a customer in the parking lot: “See that guy? He had $5,000 set aside two years ago, and I told him to buy EMC. Would’ve been worth $18,000 right now if he’d have listened.”806

When Ms. Pulliam returned to the shop three months later, tech stocks had just recovered from severe declines, but were still about 40 percent below their peaks. Said Bill, “I’m not just buying any biotechnology or high-tech stock,” but he was still sticking with his old standby, EMC. He had also just bought more Abgenix, whose share price had strongly rebounded, and his portfolio value had reached a new high.807

In February 2001, the beloved EMC shares he had purchased on margin fell to the point that his broker had to liquidate the position. The stock, which had peaked at $145 shortly after Ms. Pulliam’s first visit, eventually fell to under $4 in late 2002. Bill’s shop, once the town’s social hive, fell silent and emptied out. Observed one customer, “Everyone knows Bill has lost a lot of money. You don’t want to talk about it so much.”808

Not all of Bill’s customers got shorn; one, for instance, cashed out of his EMC stock to purchase a new home. But the damage, in general, had been done; the 2000–2002 bear market so demoralized Bill that he did not start buying stocks again until 2007, when, on the advice of a stock broker, he purchased shares in Eastman Kodak. It went bankrupt five years later; in 2013, at age seventy-three, he was still cutting hair. Even after the crash, EMC executives, who had grown understandably fond of Mr. Flynn, stopped by for haircuts during their summer vacations.809

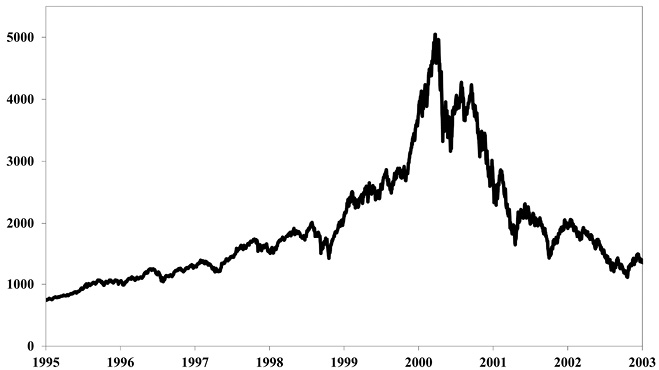

Figure 14-2. NASDAQ Composite Index 1995–2003

Bill and his customers, for the most part, got fleeced in time-honored fashion, by trading shares in individual companies, frequently on margin. But during the 1990s, increasing numbers of Americans got their stock exposure from another route: mutual funds, the direct descendants of the investment trusts of the 1920s, which provided not only easy diversification of risk through ownership of a large number of companies, but also stock selection by supposedly skilled managers. Between 1990 and 2000, the assets of U.S. stock mutual funds increased by almost twentyfold, from roughly $200 billion to $3.5 trillion—that is from about 7 percent to about 23 percent of the value of the total stock market in those two decades.810

Just like the Cape Cod barber shop denizens, mutual fund investors increasingly gravitated toward the highest fliers. The Jacob Internet Fund, one of the most popular, shot up by 196 percent in 1998, and the Van Wagoner Emerging Growth Fund gained a jaw-dropping 291 percent in 1999. Janus Capital ran an entire series of tech-heavy domestic and international funds, many of which also posted triple-digit returns that halcyon year.

The sizzling performance of these offerings attracted more assets, particularly in the burgeoning 401(k) accounts, whose sponsors thoughtfully supplied participants with fund performance statistics so that they might select the offerings with the highest recent returns.

Several strands of interwoven logic drove the tech fund mania. Most obviously, the best-performing funds attracted the largest flow of assets, which further drove up the prices of these stocks and, temporarily, the funds’ performance. The mutual fund companies, paid in proportion to the assets they manage, responded by churning out new tech funds. Finally, investors’ increasingly short time horizons drove the fund managers to trade more frenetically. In 1997, a remarkable PBS Frontline program filmed Garrett Van Wagoner, manager of his eponymous Emerging Growth Fund, emitting a near-continuous stream of trades into his phone.811 The show illustrated just how the press played along. It contained this ebullient description of Van Wagoner from Joseph Nocera, a well-known financial journalist:

The competition is fierce and the top mutual fund managers are like modern-day alchemists, creating magical market gains. And right now no one has the golden touch more than this man, Garrett Van Wagoner, who runs a one-man shop out of San Francisco.812

Ten thousand dollars invested in his fund on January 1, 1997, grew to $45,000 by March 2000 (a 350 percent return), then fell to $3,300 near the market bottom in September 2002 (a 67 percent fall from $10,000, and a 93 percent fall from top to bottom). Even these grim numbers understate the damage. The Frontline segment notwithstanding, relatively few investors knew about the fund in 1997, while it was taking off. Over the course of just the calendar year 1999 alone, the fund size grew from $189 million to $1.5 billion. Therefore, many more investors took the sickening 93 percent ride down than enjoyed the heady 350 percent way up. In the end, Nocera was right: Van Wagoner was indeed an alchemist, albeit one who transmuted gold into lead; in 2008 he finally stepped down as the manager of his eponymous portfolio, which had the worst ten-year performance of any actively managed mutual fund—a 66 percent loss of value, versus 72 percent gain for the overall stock market.813

A remarkable strand ran through the railway, 1920s, and internet bubbles: the part played by the central technologies that underlay them. Hudson depended on the newfound swiftness of rail travel to hopscotch among his offices, construction sites, shareholder meetings, and Parliament. During the 1920s bubble, speculators, even on ocean liners, eagerly perused ticker tapes fed by incoming radio signals and traded via outbound signals from shipboard trading desks. Internet chat rooms and online trading magnified the frenzy in the stocks of internet companies, which were themselves traded over the internet.

The second signature bubble symptom—the abandonment of comfortable and respectable professions for full-time speculation—also manifested itself during the internet bubble. More often than not, during the 1990s, this meant day-trading, as millions of individuals, overwhelmingly male, took time off work or even quit their employment entirely to sit in front of computer monitors and execute dozens, and sometimes hundreds, of trades per day.

Day-trading involves the rapid-fire purchase and sale of stocks and aims at numerous small profits. In an ideal day-trading world, a typical transaction might involve purchasing one thousand shares of a stock at 31½ and selling it the same day, sometimes within a few minutes, for 31⅝, resulting in a gross profit of $125. In reality, most day traders’ gross returns average close to zero and each trade gets nicked by commissions that, over hundreds and thousands of transactions, will more often than not ruin even moderately successful/lucky participants.

For sheer addictiveness, nothing matched online trading, which kept participants glued to their terminals. As one observer put it,

I do not know if many of you readers have played video poker in Las Vegas (or anywhere). I have, and it is addicting. It is addicting despite the fact that you lose over any reasonable length period (i.e., sit more than an hour or two and [nine out of ten] times you are walking away poorer). Now, imagine video poker where the odds were in your favor. That is, all the little bells and buttons and buzzers were still there providing the instant feedback and fun, but instead of losing you got richer. If Vegas was like this, you would have to pry people out of their seats with the jaws of life. People would bring bedpans so they did not have to give up their seats. This form of video poker would laugh at crack cocaine as the ultimate addiction. In my view, this is precisely what on-line trading has become.814

Before 1997, only large institutions engaged in this sort of rapid-fire trading, since small investors could not obtain the necessary favorable and accurate pricing from the stock exchanges; that year “level 2 quotes,” which display pending limit orders on their computer screens, became available to retail investors, who joined in the fun and games.

Unlike the crowd at Bill’s, most day traders are tech savvy, quantitatively gifted, and highly educated. The problem is that whenever someone buys a stock, someone else is selling it, and vice versa. In other words, security trading is akin to playing tennis with an invisible partner; what most day traders fail to realize is that almost all of the folks on the other side of the net are the investment world’s Williams sisters: savvy institutional participants to whom the company is far more than a mere symbol or computer algorithms that can steamroll human traders.

By the late 1990s, about a hundred companies established “training programs” that skipped lightly over these long odds. For several thousand dollars, “trainees” typically got three days of orientation and “boot camp” followed by a week of “paper trading.” The “trainers” dispensed optimism in tank-car quantities: Anyone could succeed if they just followed the rules. As put by one trainer, “It’s just like golf. If you’re careful about how you place your feet, how you lift the club, and follow through, you’ll stand a better chance of hitting the ball straight rather than hooking it. The same principle applies to day trading.”815

By the late 1990s, approximately five million Americans were trading online, although the number doing so full-time was estimated to be much lower.816 As long as the markets rose, the day traders stood half a chance, but just like the plungers in the 1920s and during the railway bubble, when the seas got choppy, most got wiped out.

The Beardstown ladies could not have been more different from the customers at Bill’s Barber Shop or the frenetic day traders at their desks, but the women’s trajectory was even more spectacular and just as emblematic of a gold rush atmosphere that convinced people lacking any visible expertise in finance of their bright prospects in that field.

In any other era, no one would have paid attention to a traditional investment club consisting of middle-aged and elderly homemakers in the Illinois burg of Beardstown who followed the relatively conservative playbook that had governed this small corner of American civil society for decades: gather for cookies and coffee, research established companies with reliable earnings, and hold them for the long term.

The ladies weren’t even dealing with serious money: Membership required $100 up front and $25 monthly after that. The trouble started when they began sending in their returns to the national organization, the National Association of Investors Corporation, which earned them an “All-Star Investment Club” award for six straight years. For the decade between 1984 and 1993, they reported an astonishing 23.4 percent annualized return, more than 4 percent better than the stock market.

The story of how these matrons beat Wall Street played compellingly to the 1990s narrative of casually investing one’s way to easy street. The club’s members shed their identities as small-town housewives and became full-time financial gurus. They jetted around the world, often spoke to audiences larger than the population of their hometown (pop. 5,766) that sometimes had waited in the rain for tickets, earned fat consulting fees from investment companies, and sold eight hundred thousand copies of The Beardstown Ladies’ Common-Sense Investment Guide, a compendium of their “secrets.” Remarked one, “I got off an airplane in Houston and the limousine driver was apologizing because he had to bring an extra-large car. I always used to see limos go by and say, ‘I wonder who’s in there.’ Well, now it was me in there.”817

There was just one problem with the ladies’ sudden celebrity: the 23.4 percent figure included their monthly membership dues. If one starts out with $100, earns nothing on it but adds another $25 of one’s own money along the way, one hasn’t made a 25 percent return. Sometime around 1998, more than two years after the book came out, the publisher noticed the mistake and inserted a disclaimer that stated, “this return may be different from the return that might be calculated for a mutual fund or a bank.”

During a bull market, journalistic skill atrophies; not until the 1998 edition hit the shelves did Shane Tritsch, a reporter for Chicago magazine, hardly a frontline venue for investment reporting, notice and report the disclaimer. The ladies were at first indignant, and an executive at Hyperion, their publisher, called Mr. Tritsch “malicious” and fixated on smearing “the most honest group you ever want to meet.”818

Honest mistake or not, the ladies hadn’t earned 23.4 percent for the ten years in question: 9 percent was closer to the truth. Ultimately, Hyperion withdrew the book and had to settle a lawsuit by agreeing to exchange it for any other one it published, and the ladies vanished back into obscurity.

When all was said and done, the women hadn’t done badly: for the full fifteen-year period between 1983 and 1997, auditors found that their account had earned a properly calculated 15.3 percent per year, only 2 percent worse than they would have done in an index fund, but respectable nonetheless, and certainly leagues better than the folks at Bill’s and the day-trading firms. Nonetheless, only during the 1990s could a math error turn a group of ordinary women earning mediocre stock market returns into cultural icons.

Like the Beardstown ladies, the armies of day traders, and the customers at Bill’s Barber Shop, by the late 1990s millions thought themselves stock market geniuses. The mood was best captured by the literate and insightful Barton Biggs of Morgan Stanley:

The sociological signs are very bad. . . . Everybody’s son wants to work for Morgan Stanley. Worthless brothers-in-law are starting hedge funds. I know a guy who is fifty and he’s never done anything. He’s starting a hedge fund. He’s sending out brochures to people. I’ve got one here somewhere.819

The bubble’s third symptom, vehemence, verging on raw anger, directed at doubters, became manifest by the mid-1990s. Decades before Roger Ailes made CNBC into a media powerhouse, as many as thirty million viewers tuned in Friday nights to Wall $treet Week with Louis Rukeyser, a panel show broadcast nationwide on PBS and hosted by the urbane and witty Rukeyser, himself the son of an esteemed financial journalist.

Rukeyser rigidly choreographed the show’s production, and its most coveted slots were on the rotating panel of stock brokers, analysts, and newsletter writers who bantered with him at the show’s start and later questioned the week’s featured guest. Almost as sought after was membership in his off-screen panel of “elves” who purported to predict future market direction. Rukeyser knew two things: first, that bullishness benefited his show, as well as his brand, which included two newsletters and the Louis Rukeyser Investment Cruise at Sea; and second, that a regular slot on the panels was priceless advertising for the brokers and analysts lucky enough to get one. Accordingly, he kept his panelists on a short leash, especially in the heady days of the tech bubble.

During the late 1990s, Gail Dudack, who was an analyst at UBS Warburg and a regular on both Rukeyser panels, began to get queasy. She had read Charles Kindleberger and recognized his bubble criteria, especially “displacement” and easy credit, in the then current market conditions. She warned her clients, one of whom accused her of being unpatriotic, just as her firm’s founder, Paul Warburg, had been libeled seven decades before. She thus knew how doubters got treated during bubbles: “You’ll be scorned, you’ll be terrorized, and when the bubble begins to collapse, the public will be very angry. It will need a scapegoat.” In November 1999, five months before the bubble burst, Rukeyser fired her from the show in the most humiliating way possible, on a night when she was not appearing, by drawing a dunce cap atop her image. He replaced her with an engaging Dartmouth ex-basketball player, Alan Bond, who four years later would be the recipient of a twelve-year sentence for stealing from pensioners.820

The internet bubble was hardest on “value investors” who owned stock in well-established brick-and-mortar and smokestack companies that sold at reasonable prices and lagged during the mania. Julian Robertson, a well-regarded value-oriented hedge fund manager, was forced to close down his firm, Tiger Management, which until the mid-1990s had compiled an enviable record. Remarked Mr. Robertson, “This approach isn’t working and I don’t understand why. I’m sixty-seven years old, who needs this?” Mr. Robertson announced the firm’s closing on March 30, 2000; although he could not know it at the time, the tech-heavy NASDAQ had peaked three weeks earlier at 5,060, a level it would not see for another decade and a half.821

The final identifying bubble characteristic is the presence of extreme predictions. In normal times, pundits predict market rises or falls in a given year rarely exceeding 20 percent. Forecasts outside these narrow bounds risk branding their maker as a lunatic, and most range in the single digits up or down. Not so during bubbles. James Glassman, along with his economist coauthor Kevin Hassett, wrote a book in 1999 that predicted that the Dow Jones Industrial Average would more than triple from its prevailing level of approximately 11,000 to 36,000 within a few short years. Not to be outdone, others had no choice but to raise that estimate as high as 100,000.822

The way in which Glassman and Hassett arrived at a stock market price of more than three times its then current level illustrates the lengths gone to rationalize stratospheric bubble prices. They did this by manipulating the so-called discount rate applied to both stocks and bonds. Loosely speaking, the discount rate is the return demanded by investors before they will bear the risk of owning securities; the higher the risk, the greater the return demanded (the discount rate) for owning them. For example, in mid-2019, ultrasafe long-term Treasury bonds yielded 2.5 percent, whereas the return demanded for owning much riskier stocks was roughly triple that, currently around 7.5 percent, and about 10 percent before about 1990.

The price of a long-dated asset, such as a thirty-year Treasury bond or a stock, is approximately inversely related to the discount rate: Halve the discount rate (say from 6 percent to 3 percent), and the price doubles. (Since a stock has no expiration date, it is, at least theortically, even “longer-dated” than a thirty-year Treasury.) Conversely, when the economy or global geopolitical status deteriorates, investors require a much higher return—that is, discount rate—for owning stocks, and so their prices plunge.

Glassman and Hassett’s Dow 36,000 declared that investors had evolved into a new type of homo economicus who knew that stocks weren’t so risky in the long term since they always recovered from price declines. This new human subspecies had thus decided to apply a 3 percent Treasury-like discount rate to stocks rather than the approximately historical 10 percent discount rate; this theoretically revalued their price upward by a factor of more than three (10 percent/3 percent).823

Glassman and Hassett had forgotten Templeton’s famous warning about the costliness of “This time it’s different.” Nearly simultaneously with the 2000 publication of Dow 36,000, the internet bubble foundered on the sudden return of risk, marking the denouement of the greatest financial mania of all time. Within the span of less than two years, U.S. stocks lost $6 trillion of market value, as if seven months of the nation’s entire economic output had disappeared. Whereas in 1929, only 10 percent of the households owned stocks, by 2000 the expansion of personal brokerage and mutual fund accounts, IRAs, and employment-based 401(k) plans saw stock ownership swell to 60 percent of households. Tens of millions who thought themselves financially secure found out otherwise, and millions more who considered their nest eggs adequate for retirement were forced to postpone it.

In a story as old as the financial markets, in 2000–2002 investors reacquainted themselves with the indescribable misery of sudden financial loss. In the words of humorist Fred Schwed,

There are certain things that cannot be adequately explained to a virgin either by words or pictures. Nor can any description I might offer here even approximate what it feels like to lose a real chunk of money that you used to own.824

771. Edward Wyatt, “Fox to Begin a ‘More Business Friendly’ News Channel,” The New York Times, February 9, 2007.

772. Peter Elkind et al., “The Trouble With Frank Quattrone was the top investment banker in Silicon Valley. Now his firm is exhibit A in a probe of shady IPO deals,” Fortune, September 3, 2001, http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2001/09/03/309270/index.htm, accessed November 17, 2016.

773. McLean and Elkind, 234.

774. John Schwartz, “Enron’s Collapse: The Analyst: Man Who Doubted Enron Enjoys New Recognition,” The New York Times, January 21, 2002.

775. Ibid.

776. Richard A. Oppel, Jr., “Merrill Replaced Research Analyst Who Upset Enron,” The New York Times, July 30, 2002.

777. Howard Kurtz, The Fortune Tellers (New York: The Free Press, 2000), 32.

778. Scott Tong, “Father of modern 401(k) says it fails many Americans,” http://www.marketplace.org/2013/06/13/sustainability/consumed/father-modern-401k-says-it-fails-many-americans, accessed November 1, 2016.

779. Jeremy Olsham, “The inventor of the 401(k) says he created a ‘monster,’” http://www.marketwatch.com/story/the-inventor-of-the-401k-says-he-created-a-monster-2016-05-16; and Nick Thornton, “Total retirement assets near $25 trillion mark,” http://www.benefitspro.com/2015/06/30/total-retirement-assets-near-25-trillion-mark accessed November 11, 2016.

780. The most easily available current report on the gap between IRR and fund returns is Morningstar’s annual “Mind the Gap” report, available at https://www.morningstar.com/lp/mind-the-gap?cid=CON_RES0022; on average, investors lose about 1 percent of return per year of return from poor timing; this is on top of fund expenses, which also average around 1 percent.

781. Aaron Heresco, Shaping the Market: CNBC and the Discourses of Financialization (Ph.D. thesis, Pennsylvania State University, 2014), 81.

782. Gabriel Sherman, The Loudest Voice in the Room (New York: Random House, 2014), 5–9.

783. Joe McGinnis, The Selling of the President, 1968 (New York: Trident Press, 1969), 64–65.

784. Cassidy, 166.

785. Sherman, 146–147.

786. Heresco, 88–115; and Mahar, 156–157.

787. Heresco, 151–152.

788. Ekaterina V. Karniouchina et al., “Impact of Mad Money Stock Recommendations: Merging Financial and Marketing Perspectives,” Journal of Marketing Vol. 73 (November 2009): 244–266; and J. Felix Meshcke, “CEO Appearances on CNBC,” working paper, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.203.566&rep=rep1&type=pdf, accessed November 12, 2016; and for Cramer/Bartiromo, see Kurtz, 207.

789. Kurtz, 117–118.

790. Heresco, 232.

791. James K. Glassman, “Is Government Strangling the New Economy?,” The Wall Street Journal, April 6, 2000. (In the interest of full disclosure, the Journal published a dyspeptic letter to the editor by this author in response to Mr. Glassman’s editorial, “The Market Villain: It’s Not Your Uncle,” April 19, 2000.)

792. George Gilder, “The Faith of a Futurist,” The Wall Street Journal, January 1, 2000.

793. The other two questions in Frederick’s battery: (1) If it takes 5 machines 5 minutes to make 5 widgets, how long would it take 100 machines to make 100 widgets? Answer = 5 minutes. (2) In a lake, there is a patch of lily pads. Every day, the patch doubles in size. If it takes 48 days for the patch to cover the entire lake, how long would it take for the patch to cover half of the lake? Answer = 47 days. Over the past decade, the baseball/bat question has become so well known in economics and finance that it’s now hard to stump anyone in these fields with it.

794. Shane Frederick, “Cognitive Reflection and Decision Making,” Journal of Economic Perspectives Vol. 19, No. 4 (Fall 2005): 25–42. For the Four Card Task, see P. C. Wason, “Reasoning,” in B.M. Foss, Ed., New Horizons in Psychology (New York: Penguin, 1966), 145–146.

795. David L. Hull, Science and Selection (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 37.

796. Keith E. Stanovich et al., The Rationality Quotient (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2016), 25–27. For an extensive sample of CART questions and scoring, see ibid., 331–368. Quote from Keith E. Stanovich, “The Comprehensive Assessment of Rational Thinking,” Educational Psychologist Vol. 51, No. 1 (February 2016): 30–31.

797. R.B. Zajonc, “Feeling and Thinking,” American Psychologist Vol. 35, No. 2 (February 1980): 155, 169–170.

798. Daniel Kahneman, slide show for Thinking Fast and Slow, thinking-fast-and-slow-oscar-trial.ppt.

799. Isaiah Berlin, The Proper Study of Mankind (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998), 436–498, quote 436.

800. Tetlock, 15, quote 56.

801. Dan Gardner and Philip Tetlock, “What’s Wrong with Expert Predictions,” https://www.cato-unbound.org/2011/07/11/dan-gardner-philip-tetlock/overcoming-our-aversion-acknowledging-our-ignorance.

802. Tetlock, 138.

803. Tetlock, 42–88, 98, 125–141, quote 63.

804. Susan Pulliam, “At Bill’s Barber Shop, ‘In Like Flynn’ Is A Cut Above the Rest—Owner’s Tech-Stock Chit-Chat Enriches Cape Cod Locals; The Maytag Dealer Is Wary,” The Wall Street Journal, March 13, 2000, A1.

805. Personal communication, Susan Pulliam.

806. Pulliam, “At Bill’s Barber Shop, ‘In Like Flynn’ Is A Cut Above the Rest—Owner’s Tech-Stock Chit-Chat Enriches Cape Cod Locals; The Maytag Dealer Is Wary.”

807. Susan Pulliam and Ruth Simon, “Nasdaq Believers Keep the Faith To Recoup Losses in Rebound,” The Wall Street Journal, June 21, 2000, C1.

808. Susan Pulliam, “Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow: Tech Ills Shave Barber,” The Wall Street Journal, March 7, 2001, C1.

809. Jonathan Cheng, “A Barber Misses Market’s New Buzz,” The Wall Street Journal, March 8, 2013, and Pulliam, “Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow: Tech Ills Shave Barber.”

810. Source: Investment Company Institute 2016 Fact Book from ici.org for U.S. equity fund holdings, and total market cap from http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/CM.MKT.LCAP.CD?end=2000&start=1990, both accessed December 17, 2017.

811. Van Wagoner clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i9uR6WQNDn4.

812. From transcript of “Betting on the Market,” aired January 27, 1997, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/betting/etal/script.html, accessed December 17, 2016.

813. Diya Gullapalli, “Van Wagoner to Step Down As Manager of Growth Fund,” The Wall Street Journal, August 4, 2008; total returns calculated from annualized returns. See also Jonathan Burton, “From Fame, Fortune to Flamed-Out Star,” The Wall Street Journal, March 10, 2010.

814. Clifford Asness, “Bubble Logic: Or, How to Learn to Stop Worrying and Love the Bull,” working paper, 45–46, https://ssrn.com/abstract=240371, accessed on November 12, 2016.

815. Mike Snow, “Day-Trade Believers Teach High-Risk Investing,” The Washington Post, July 6, 1998.

816. Arthur Levitt, testimony before Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Committee on Governmental Affairs, September 16, 1999, https://www.sec.gov/news/testimony/testarchive/1999/tsty2199.htm, accessed December 29, 2019.

817. Mark Gongloff, “Where Are They Now: The Beardstown Ladies,” The Wall Street Journal, May 1, 2006.

818. Calmetta Y. Coleman, “Beardstown Ladies Add Disclaimer That Makes Returns Look ‘Hooey,’” The Wall Street Journal, February 27, 1998.

819. Cassidy, 119.

820. Mahar, 262–263, 306–309, quote 307; for Bond sentencing, see “Ex-Money Manager Gets 12 Years in Scheme,” Los Angeles Times, February 12, 2003.

821. Gregory Zuckerman and Paul Beckett, “Tiger Makes It Official: Funds Will Shut Down,” The Wall Street Journal, March 31, 2000. During the late 1990s, the author personally experienced a milder version of this kind of pushback on a few occasions at little cost, but quickly learned to keep his opinions about tech stocks to himself. The reader might also reasonably wonder how well he, forewarned by Extraordinary Popular Delusions, and given the failure of Mackay to appreciate the railway mania that occurred shortly following its publication, interpreted the late 1990s tech bubble as it unfolded. By happy coincidence, he published a personal finance title in 2000, at the bubble’s height, The Intelligent Asset Allocator (New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 2000). The ongoing bubble, as yet un-burst, was discussed at length on pages 124–132; see especially the brief mention of Extraordinary Popular Delusions on page 178. These extracts are available with the very kind permission of McGraw-Hill, Inc., at http://www.efficientfrontier.com/files/TIAA-extract.pdf.

822. Charles W. Kadlec, Dow 100,000 (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Press, 1999).

823. James K. Glassman and Kevin A. Hassett, Dow 36,000 (New York: Times Business, 1999); and Charles W. Kadlec, Dow 100,000 Fact or Fiction (New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1999).

824. Schwed, 54.