Briefly Rich

Throughout the length and breadth of the land, men’s minds were engrossed by the same subject. Party politics were absorbed by it. Whig and Tory left off squabbling, and Jacobites ceased to plot. At every inn, on every road, throughout the country, the talk was the same. At Aberystwith, and Berwick-on-Tweed, at Bristol and St. David’s, at Harwich and Portsmouth, at Chester and York, at Exeter and Truro—almost at the Land’s End—the talk was only of South Sea Stock—nothing but South Sea Stock!

—William Harrison Ainsworth, 1868162

In the early eighteenth century, John Law, a brilliant Scottish financier, left behind a lurid trail of financial chaos hauntingly familiar to those savaged by the collapse of the 1990s internet bubble. Internet stocks merely damaged millions of investors; Law damaged France’s faith in banks, a far more serious blow to a nation.

The young Scotsman hailed from a centuries-old lineage of distinguished Edinburgh goldsmiths that included his father, uncle, and three brothers. By the time of his birth in 1671, the very word “goldsmith” camouflaged that ancient profession’s evolution into something quite different: banking.

Law’s immediate ancestors lived on an island that bore no resemblance to the future majestic, free-trading Britannia. (And at the time, Scotland was, in any event, still independent from England.) As the seventeenth century dawned, the population of the future Great Britain was only a third that of France’s—smaller than before the arrival of the Black Death in 1348–1349. The England of Law’s era was weak, underdeveloped, and recently embroiled in a regicidal civil war, and its presence on the high seas involved piracy and smuggling as much as commerce. High-volume international trade had only just begun to slowly appear with the establishment of large trading organizations around 1600, the most famous of which was the East India Company.

When East India ships bearing gold and silver from the nascent spice trade sailed into London, their merchants met an immediate logistical problem: England had no banking system, and thus no reliable place to deposit their treasure. Goldsmiths, whose livelihoods depended on the safe storage of valuables, provided the most obvious alternative. In exchange for their valuables, the merchants received certificates. Critically, this paper could be exchanged for goods and services—in other words, it functioned as currency. Further, the goldsmiths tumbled onto the fact that they could create paper in excess of the amount of gold and silver (specie) they held.

This is to say, the goldsmiths could print money.

Only the most mendacious and shortsighted among them would manufacture and then spend their own certificates; rather, these pieces of paper were loaned out at high rates of interest. Since the prevailing rate for even the best borrowers was often well in excess of 10 percent per year (especially when England was at war), over a decade’s span, lending a certificate was better than spending it, and it would remain so as long as the goldsmith remained solvent.

This daisy chain worked only so long as a large number of certificate holders didn’t redeem them all at once. Say the goldsmith’s safe contained £10,000 of specie, and he had issued £30,000 worth of certificates—one-third issued to the specie’s owners and two-thirds to borrowers. If the holders of £10,001 of the certificates showed up demanding gold or silver—it did not matter whether they were borrowers or the original depositors—the goldsmith could be ruined. Worse, if the certificate holders even suspected this could happen, the growing line at the goldsmith’s office would suffice to precipitate a run that would topple the entire house of cards. In this example, the ratio of certificates to specie was 3:1; the higher this ratio, the more probable a run. Even the most careful goldsmith/bankers could come to grief; between 1674 and 1688 four documented “goldsmith runs” occurred, and between 1677 and the establishment of the Bank of England in 1694, the number of London goldsmith/bankers fell from forty-four to around a dozen.

As a practical matter, the goldsmith/bankers found a 2:1 ratio—£1 loaned to borrowers for every £1 of specie on deposit—reasonably safe. The importance of this system cannot be understated, for it heralded the birth of an elastic money supply that could be resized according to the hunger of borrowers for loans and the willingness of creditors to lend. When borrowers and lenders were euphoric, the money supply expanded, and when they were frightened, it contracted. The modern financial term for the amount of paper monetary expansion is “leverage”: the ratio of total paper assets to hard assets.163

Bank-supplied leverage is the fuel that powers modern financial manias, and its birth in seventeenth-century Europe brought with it a roller coaster of bubbles and busts. Over the next four centuries, financial innovation has yielded a dizzying variety of investment vehicles; each, in its turn, was often simply leverage in a slightly different disguise, and would prove the tinder that would set alight successive waves of speculative excess.

The descendant of goldsmiths who had adopted English-style banking, John Law thus lived and breathed a system in which paper could function as money just as well as scarce specie. Even today, many resist the notion of paper money; at the turn of the seventeenth century, it struck the average person as ludicrous.

By 1694, the young Law, weary of filthy, poor, late-medieval Edinburgh, made his way to London, where he fashioned himself as Beau Law, a rakish man about town, especially at the gambling tables, and engaged in a duel with one Beau Wilson over their mutual interest in a young lady that resulted in Wilson’s death. Tried, convicted to hang, then reprieved, then again sentenced to hang, Law escaped. The London Gazette in early 1695 read:

Captain John Lawe, a Scotchman, lately a Prisoner in the King’s-Bench for Murther, age 26, very tall black lean Man, well shaped, above Six foot high, large Pockholes in his Face, big high-Nosed, speaks broad and low, made his Escape from said Prison. Whoever secures him, so as he may be delivered at the said Prison, shall have £50 paid immediately by the Marshal of the King’s-Bench.164

In the late seventeenth century, prisoners managed “escape” more easily than today, and Law’s friends, with the likely connivance of King William III, probably arranged his flight.165 The above physical description intentionally misled, since Law had an average-sized nose and fair complexion.

Initially, he traveled to France, where his mathematical ability astonished his contemporaries and served him well at the gambling tables. To have called Law a gambler, though, did not do his skills justice. Even today, quantitative ability and unblinking concentration serve well at the poker and blackjack tables (so long as the blackjack dealer does not shuffle between hands). Three hundred years ago, the less efficient casinos rewarded dispassionate calculation yet more richly. These opportunities attracted some of Europe’s brightest mathematicians to games of chance, most famously Abraham de Moivre, whose The Doctrine of Chances forms much of the groundwork of modern statistics.166 Wrote one acquaintance of Law’s skills,

You asked me for news of Mr. Law. He only sees other players with whom he plays from morning to night. He is always happy when gambling and each day proposes different games. He offered 10,000 sequins to any who could throw six sixes in a row, but each time that they fail to do so they give him a sequin.167

Since the odds of rolling six consecutive sixes are one in 46,656 (one in 66), Law’s offer was a winning proposition. (From his perspective, the odds of losing or paying out before 10,000 series of six throws was 19 percent.) Further, whenever Law could, he served as “banker” at cards, which, depending on the rules of the particular game, usually conferred on him a small statistical advantage, since it allowed him to function as the casino, not as a customer.168

When Law left for France, he leveraged his casino winnings, estimated by economic historian Antoin Murphy to have totaled hundreds of thousands of pounds sterling, a massive fortune for the time.169 He then decamped for Holland, where he observed firsthand the cutting-edge operations of both the Bank of Amsterdam and the city’s new stock exchange. He also visited Genoa and Venice, where he familiarized himself with their centuries-old banking systems.

Because Frenchmen of that era did not trust their nation’s governing institutions, the nation’s banking system was nearly nonexistent. The spare livre went under the mattress or into a sock, not into a bank, thus depriving the economy of sorely needed capital.170 Law marveled at the advanced financial systems in Italy and Holland, and endeavored to bring their benefits to France; in the decade or so of his continental peregrinations, he transformed himself from Law the professional gambler to Law the economist, a term that had yet to be invented.

Law intuitively understood how a stingy supply of money based on scarce gold and silver had strangled European economies, and how a generous one might stimulate them. Already familiar with the notion of privately issued paper money, his experience with Dutch banking hinted that paper money issued by a central national bank might solve the problem of an inadequate monetary base.

Law’s intuition of how an ample supply of paper currency can prove an economic tonic can be understood via the famous story (at least among economists) of a babysitting cooperative in Washington, D.C., three centuries later. Such a cooperative involves the trading of childcare services. One of the most popular schemes involves the use of “scrip”: paper chits, each worth one half hour of sitting; a couple desiring a three-hour movie outing would thus need six chits.

The success of such scrip/chit schemes depends greatly on the precise amount of chits in circulation. In the early 1970s, one such co-op in Washington, D.C., printed a stingy number of chits, and so parents horded them. Many were willing to babysit to earn chits, but fewer were willing to spend them, and so everyone spent fewer nights out than they would have liked.

This being Washington, D.C., many of the parents were lawyers, and, as lawyers are wont to do, they legislated a solution by mandating individual spending of the chits. In the economic sphere, legislative solutions often fail, as happened in this case, whereupon an economist couple convinced the co-op to print and hand out more. Flush with chits, parents spent them freely and so spent more nights out.171

In similar fashion, Law’s goldsmith/banking background and experiences told him that Europe’s economic stagnation was due to a shortage of specie, which could be remedied by, among other actions, printing paper money. Law was not the first to realize this; almost from the invention of elastic credit by the goldsmith/bankers in the early seventeenth century, some of them realized that monetary expansion with paper currency could be used to stimulate an economy. Three centuries before John Maynard Keynes famously labeled a gold-based monetary system a “barbarous relic,” William Potter, a royal official, noted in 1650 that the limited amount of specie in circulation meant that,

though the Store-house of the world be never so full of Commodity, yet seeing the Tradesman cannot afford to take it in faster than he can find sale for what he hath already, it follows that if the people through their extreme poverty are not able to take it off from the hands of the Tradesman, the door in that respect is shut against Trade, and by consequence against Wealth. . . . On the other side, let it be supposed that money (or that which goes for such) doth increase among them; it follows that (they not hoarding it up, but laying it out in commodity, as fast as they receive it) the more their hands are filled with such money, by the increase thereof, so much more doth the sale of Commodity, that is Trading increase; and this increase of Trading doth increase Riches. . . . Therefore increase of money, or that which goes for such, not hoarded up, is the Key of Wealth. (italics added)172

The banking systems in France and in his native Scotland were far more primitive than the ones Law encountered in Holland and in Italy, and as a result the French and Scottish economies functioned poorly. He was particularly struck by the parlous state of the textile industry in the Rhône Valley, and he formulated a plan for factories, nurseries, bakeries, and mills financed by the issue of paper money. In late 1703, one of his contacts, the French Ambassador in Turin, transmitted his proposal to the Marquis de Chamillart, France’s controller general, who politely rejected it.

Sometime around the new year, Law returned home to Scotland, where things were in even greater flux. Earlier, in 1695, the Scottish Parliament had granted a monopoly on that nation’s long-distance commerce to the Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies, better known as the Darien Company. Its plan was to establish a trading outpost on the Isthmus of Panama at Darien in order to shorten the route from Europe to Asia. The company sent two expeditions to the Isthmus, the first of which failed because of poor planning and supply, while the second was decimated by the Spanish.

When the outpost fell to the Spanish in 1699, the Bank of Scotland had to suspend operations. The bank’s difficulties profoundly affected Law and so further refined his economic thinking, resulting in two tracts, Essay on a Land Bank and Money and Trade Considered. The former proposed the issuing of paper money backed by land; and the latter was a detailed and incisive book that foreshadowed by seventy years many of the concepts in Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations.

Law began to think deeply about the nature of money in a remarkably modern way. True money, he postulated, had seven essential features: stability of value, homogeneity (that is, it could be traded in constant units), ease of delivery, sameness from place to place, storability without loss of value, divisibility into smaller or larger quantities, and possessing a stamp or identification as to its value.173

Law thought that land met these criteria, and paper money yoked to it would be superior to a conventional currency anchored to silver. The notion of money denominated in units of land today seems odd, but in the early eighteenth century it made good sense. Beginning around 1550, silver flooded into Europe from the vast mines in Peru and Mexico, thus eroding its value. A certificate denoting a given piece of land, by contrast, could be valued according to the sum of its future grain, fruit, or animal production. In addition, silver has only a few circumscribed uses: as money, in jewelry and utensils, or in industrial employment. Land, by contrast, can simultaneously back paper money and be used in a wide range of agriculture.174 As Law wrote, “Land is what produces everything, silver is only the product. Land does not increase or decrease in quantity, silver or any other product may. So land is more certain in its value than silver, or any other goods.”175

Law gradually broadened his definition of money beyond land to include the shares in the era’s great companies, particularly the English and Dutch East India companies and the Bank of England, whose profits, he thought, should likewise prove more stable than silver. This was a reasonable assumption; what Law did not foresee is that his system would itself introduce a fatal instability into those prices.

Foreshadowing Karl Marx, he postulated a three-stage progression of societal development. In the first stage, without money, barter served as the main form of exchange, under which large-scale manufacture was nearly impossible, since it requires significant up-front monetary outlay. In Law’s words, “In this state of barter there was little trade, and few arts-men.” (Law used the word “trade” in the modern sense of GDP: the total amount of goods and services consumed. In the modern era, the concept of barter in the pre-money era is recognized to be incorrect, since in aboriginal societies exchange is done by extending favors and accumulating markers, a state of affairs even more economically inefficient than barter.)176

In the second stage, the economy ran on metallic money, but far too little of it. While it is theoretically possible that if money is scarce, men would work for lower wages, manufacture is still stunted:

It will be asked if countries are well governed why they do not process their wools and other raw materials themselves, since, where money is rare, labourers work at cheap rates? The answer is that work cannot be made without money; and that where there is little, it scarcely meets the other needs of the country, and one cannot employ the same coin in different places at the same time.177

In the third stage, when money and credit were plentiful, nations prosper. A case in point was England, which just a decade earlier had established the note-issuing Bank of England. The Bank periodically expanded and contracted the note supply; Law observed that “as the money in England has increased, the yearly value of [national income] has increased; and as the money has decreased, the yearly value has decreased.”178

The heart of Law’s theory, explained in a several-page passage in Money and Trade Considered, described, for the first time, an economic concept known as “the circular flow” model, which can be imagined as two concentric circles, with money flowing from one owner to another in clockwise fashion, and goods and services flowing in a counterclockwise fashion.

Law imagined an isolated island owned by a lord who rented out his land to one thousand farmers who grew crops and raised animals constituting 100 percent of the island’s output. Manufactured items could not be produced locally, but rather were imported in exchange for the island’s excess grain.

Furthermore, the island contained another three hundred unemployed paupers who subsisted on the charity of the lord and farmers. Law’s solution to this sad state of affairs involved the lord printing up enough currency to establish factories that would employ as workers the three hundred paupers, whose wages would pay the farmers, now no longer idle, for food, and this would increase rents to the lord, with which he could continue to pay the workers.

Law summarized his example as any modern Keynesian would:

Trade [in modern terms, GDP] and money depend mutually on one another: when trade decays, money lessens; and when money lessens, trade decays. Power and wealth consists in numbers of people, and magazines [warehouses] of home and foreign goods; these depend on trade, and trade on money. So while trade and money may be affected directly and consequentially; that which is hurtful to either, must be so to both, power and wealth must be precarious.179

Law proposed a scheme for paper-note issuance by the Bank of Scotland, which that nation’s parliament voted down in 1705. Two years later, Scotland passed the Act of Union, which, by merging it with England, put Law’s neck at risk in Scotland, since he was still subject to imprisonment and execution in London. Law requested a pardon from Queen Anne, and when she turned him down, he fled back to the Continent, bouncing around among Holland, Italy, and France for a decade before alighting in Paris in 1715.180

During that time, he was once again turned down by Controller General de Chamillart and saw another plan for a bank in Turin nixed by the Duke of Savoy. Daringly, he next solicited the support of Louis XIV, who by that point, in the summer of 1715, had reigned seventy-two years, a record for European monarchs that stands to this day. (Queen Elizabeth will have to live until age ninety-eight, in 2024, to exceed Louis’s span.) Louis was about to approve Law’s proposal when he developed gangrene, memorably telling the regent, the Duke of Orléans, “My nephew, I make you regent of the kingdom. You are going to see one king in the tomb and another in the cradle; always keep in mind the memory of the former and the interests of the latter.”181 The attractive, charming, and wealthy Law cultivated the regent, and eventually persuaded him to undertake a grand financial experiment.

At the time of Louis’s death in September 1715, France had been bankrupted by the recent War of the Spanish Succession. Law had sought to organize a large state bank, but beginning in 1716 the regent limited him to the establishment of the Banque Générale Privée, a private firm, as its name indicated, headquartered in the home of Law, a newly minted French citizen.

At the time, only five states—Sweden, Genoa, Venice, Holland, and England—issued paper notes that did not function as everyday small-scale transactions, so Frenchmen regarded the new bank’s notes suspiciously.182 Law immediately mandated that they be convertible one-to-one into the gold and/or silver in circulation at the time of the bank’s establishment. Since France, a chronically insolvent state, regularly debased its national coinage, this drove the new paper currency’s value to a premium over that of the then circulating coins. To attract wealthy customers and increase confidence, he kept his reserve ratio low and offered several “loss leaders,” including free foreign currency conversions and payment for the bank’s notes at their face value, instead of at the much lower (highly discounted) price of ordinary government paper notes.183

Because they were guaranteed at par value, the desirability of Law’s bank’s notes and services could not help but attract attention. And just as Law predicted, the increased paper money supply perked up the kingdom’s economy.

Law next targeted the Mississippi Company. Originally chartered in 1684, it later obtained monopolies on trade with French America through its mergers with other companies that held them, but it had been so unsuccessful at exploiting those monopolies that its manager, Antoine Crozat, turned his franchise back over to the crown in 1717. Law’s reputation, now burnished by the success of the Banque Générale Privée, promised to save the nation’s parlous finances by having the Mississippi Company buy up the crown’s massive debt. In the process, Law multiplied his already staggering gambling wealth through speculation in the company’s shares.

In order to enable the Company to do this, he had the crown expand its monopoly to trade with China, the East Indies, and the “South Seas”—all the oceans south of the equator—even though almost all of the relevant trade routes were under the control of England, Spain, and Portugal.184 The inconvenient fact that the Company’s “monopoly” on New World trade was worth little did not detract from the glamour of Law’s new financial machinery.

The Company now held the crown’s massive debt, mainly in the form of billets d’état by its citizens, which were then yielding 4 percent. Because of the kingdom’s weakened financial state, the billets traded at a large discount to their face value; Law promised that his scheme would drive their price up to par, an offer the crown found irresistible. In December 1718, Law’s successes allowed him to convert his Banque Générale Privée into a national bank, the Banque Royale, which completed the paper daisy chain: the new Banque would issue notes that would pay for shares in the Mississippi Company, which would buy up the billets and so mitigate the crown’s war debts. Even more confusingly, Company shares could also be bought directly with billets; since the billets were debt, their disappearance in exchange for shares further improved the crown’s finances.185

Law’s power allowed him to indulge his war against silver currency, which he saw as the nation’s economic ball and chain. Coins were out, and paper was in. The government had previously allowed tax payments to be made in his private bank’s notes, and in early 1719, the Banque Royale established branches in the largest French cities, where silver transactions of more than six hundred livres had to be made in the bank’s own notes or in gold; silver payment was forbidden. By late 1719, the Banque had bought up most of the billets, and the extinction of the nation’s debt further buoyed the nation’s animal spirits.

As the share price of the Mississippi Company rose, the bank printed more notes to meet the demand for the shares, further driving up their price, which then caused yet more note issuance. Soon, the first well-documented nationwide stock bubble was in process. The heedless monetary expansion was not entirely the work of Law, who understood the nature of an inflationary spiral, but also reflected the influence of the regent, who, buoyed by the scheme’s success, did not comprehend this risk.

A modern company operates with what is known as “permanent capital,” which is simply a fancy way of saying that if it needs a billion dollars for a given project, much of the money is raised from stock sales, and if the expense projections are accurate, the project will subsequently be completed.

Not so with Mississippi Company shares. Rather than being purchased outright for their full price, shares were sold by subscription—in the Company’s case, for cash at a 10 percent premium. To acquire a share, purchasers had to pay only the 10 percent premium and the first of twenty monthly installments, or “calls,” of 5 percent each—that is, a total of 15 percent of the share price. The call mechanism was an early form of financial leverage, and it served to magnify both gains and losses—if the price increased by 15 percent, the value of the investor’s initial down payment doubled; and if the price fell by 15 percent, the investor was wiped out. The call structure can thus be thought of as the great-great-grandfather of the margin debt that underlay many subsequent financial crashes, most notably in 1929.186

To meet the demand for Company shares, Law’s bank issued more of them; Charles Mackay described what happened next:

At least three hundred thousand applications were made for the fifty thousand new shares, and Law’s house in the Rue de Quincampoix was beset from morning to night by eager applicants. As it was impossible to satisfy them all, it was several weeks before a list of the fortunate new stockholders could be made out, during which time the public impatience rose to a pitch of frenzy. Dukes, marquises, counts, with their duchesses, marchionesses, and countesses, waited in the streets for hours every day before Mr. Law’s door to know the result. At last, to avoid the jostling of the plebian crowd, which, to the number of thousands, filled the whole thoroughfare, they took apartments in the adjoining houses, that they might continually be near the temple whence the new Plutus was diffusing wealth.187

People talked of little else, and nearly every member of the aristocracy who was lucky enough to own stock was busy buying and selling it. Rents on Rue de Quincampoix rose fifteenfold.

Law grew weary of the crowds and decamped for a residence in the more spacious Place Vendôme, but it too soon filled to capacity and attracted the ire of the chancellor, whose court lay on the square. Finally, Law moved to the Hôtel de Soissons, which had a garden large enough to accommodate the several hundred tents that sprang up; the lucky prince who owned the property rented them out for five hundred livres per month each.

Mackay recounted that “peers, whose dignity would have been outraged if the regent made them wait half an hour for an interview, were content to wait six hours for the chance of seeing Monsieur Law.”188 One lady cleverly exploited Law’s famous gallantry by having her coachman overturn her vehicle in his presence. He predictably rose to her assistance; she soon confessed the ruse and so amused Law that he issued her shares. The prudish Mackay mentioned another episode that would make the reader “smile or blush according if he happens to be very modest or the reverse,” but did not describe it, coyly leaving behind only a reference to a letter written by the Duchess of Orléans:

Law is so run after that he has no rest day or night. A duchess kissed his hands before everyone, and if duchesses kiss his hands, what parts of him won’t the other ladies salute?189

Other observers confirmed Mackay’s lurid descriptions. In September 1719 a British embassy clerk reported to London that

the rue de Quinquempoix, which is their Exchange Alley, is crowded from early in the morning to late at night with princes and princesses, dukes and peers and duchesses etc., in a word all that is great in France. They sell estates and pawn jewels to purchase Mississippi.

A week later, the same clerk wrote that “all the news of this town is of stock jobbing. The French heads seem turned to nothing else at present.”190 Paris became a boom town. During the bubble, its population swelled and the city suffered the inevitable side effects of ballooning prices for food, services, and real estate. In that heady milieu, the word “millionaire” first came into common usage to describe lucky shareholders.191 Another embassy report read, “I was told yesterday that a shop had sold in less than three weeks lace and linen for 800,000 livres and this chiefly to people who never wore any lace before; the accounts of this kind everyday are so very extraordinary that will scarcely be believed in other countries.”192

Bubbles typically end with a seemingly small disturbance, followed by a swift collapse. The tremor came in early 1720, when Prince de Conti, angered that he had not received a large enough allotment of the Company’s stock, sabotaged it by sending to the Banque Royale three wagons to be filled with the gold and silver coin that supposedly backed the bank’s new paper money. Law, who was by then the comptroller general of France—essentially, the prime minister—could not be seen refusing this disastrous request, so he did the next best thing: he complained to the regent, who forced Conti, an unpopular man, to back down. Perceptive investors sussed out the significance of the prince’s demand and the regent’s tacit refusal: The volume of the bank’s outstanding notes grossly exceeded its reserves of gold and silver. A full-fledged run on the bank ensued.

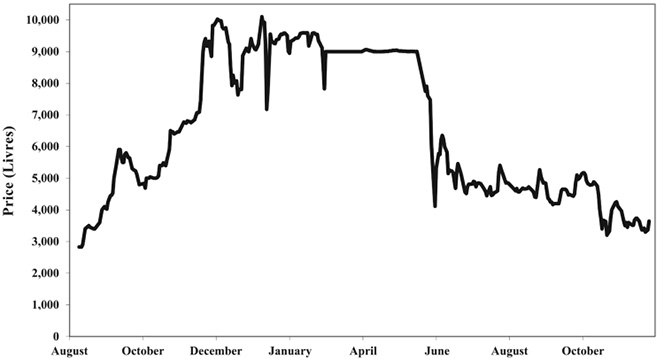

Figure 3-1. Mississippi Company Share Price 1719–1720

Law now faced a dire choice. He could protect the currency by refusing to print more notes, which would damage share prices, or he could protect the share price by printing more notes to buy back shares at a floor price, which would worsen the already rampant inflation. The latter action would protect the aristocratic investors; the former would protect France.

Initially, Law chose to protect the currency, and thus the nation, or so he thought. In desperation, in late February 1720, he and the regent forbade trading in specie and limited personal possession to five hundred livres in coin; the hoarding of silver plate and jewels was also forbidden, and informers and agents were recruited to enforce the odious new rules. The nation’s social fabric began to unravel as servants ratted out masters and fathers betrayed sons.

So great was the social disruption that two weeks later Law switched gears to protect the share price, and thus the wealthy, by offering to pay nine thousand livres per share, which meant printing yet more bank notes. By then, the ensuing inflation brought about by the debasement of the livre was obvious, and in May he devalued the currency by 50 percent in two steps. Later in 1720, in an attempt to control inflation, he declared worthless large denomination bank notes, wiping out much of the nation’s fortunes; economic historian Antoin Murphy estimates that the inflation-adjusted value of the entire system, consisting of Mississippi Company shares and banknotes, fell by approximately 87 percent. The final blow to Law’s scheme of bank notes and Mississippi Company shares came that fall, when the plague ravaged Marseille and threatened Paris, further hobbling financial confidence.193

By this point, he had exhausted not only the Banque’s capital, but his political capital as well. The regent, wishing to avoid further embarrassment, allowed him to depart Paris gracefully, first to the city’s outskirts, and then abroad. Law, who by this point had received a royal pardon for the murder of Beau Wilson, spent his last years bouncing around England and the Continent and fending off creditors, the most famous of whom was Lord Londonderry, with whom he had placed a bet in September 1719 that the Mississippi Company would damage England’s East India Company. The bet had Law effectively “short” the EIC’s stock by promising to deliver a large amount of shares to Londonderry at a later date. (A “short” is a wager on a share price fall.) Not only did the EIC’s share price rocket during the South Sea Bubble, the Mississippi Company’s London twin, but Law’s scheme had greatly devalued the French currency relative to England’s, making the bet yet more disastrous for him.194

Although Law had become a political liability to the Duke of Orléans, the regent still valued his brilliance, and he might have been recalled to Paris had not the regent died in 1723. In the event, Law succumbed a poor man in his beloved Venice in 1729, his major asset by this point a substantial collection of art, and little else. All in all, he was lucky; future bubble protagonists often met grimmer ends.195

The Company did possess what eventually became the Louisiana Territory, but in the early eighteenth century it was underpopulated and malarial. In order to recruit settlers for the Company’s New World operations, Law had produced fraudulent brochures describing it as an earthly paradise. When his advertising campaign failed, Law fell back on the conscription of thousands of white prisoners of both sexes and African slaves:

Disorderly soldiers, black sheep of distinguished families, paupers, prostitutes, and any unsuspecting peasants straying into Paris were taken and transported by force to the Gulf Coast. Those who voluntarily came were offered free land, free provisions, and free transportation to the new territory.196

Louisiana’s “capital,” which alternated between modern-day Biloxi and Mobile, was little more than a deadly, fetid encampment of several hundred settlers, most of whom decamped for the new capital in New Orleans after the Company’s collapse in 1721.197

For two centuries, history painted Law as a scoundrel. Typical was the advice of Daniel Defoe (writing under the nom de plume of Mr. Mist) to someone wishing to achieve great wealth:

Mr. Mist says, if you are resolv’d upon it and nothing else will serve you but to do just so, what need you ask what you must do? The Case is plain, you must put on a Sword, Kill a Beau or two, get into Newgate, be condemned to be hanged, break Prison, IF YOU CAN,—remember that by the Way,—get over to some Strange country, turn Stock-Jobber, set up a Mississippi Stock, bubble a Nation, and you may soon be a great Man; if you have but great good luck, according to an old English Maxim:—

Dare once to be a Rogue upon record,

And you may quickly hope to be a Lord.198

Economic historians have been more kind. In Law’s time, the idea of running an economy without gold- and silver-based money seemed revolutionary, even ludicrous. The overwhelming majority of today’s economists believe that it is even more foolish to base the money supply on the amount of metal emanating from the ground or from people’s jewelry boxes. Economic historian Barry Eichengreen, for example, an authority on the gold standard, observed that nations recovered from the Great Depression in the precise order they abandoned hard money.199 In essence, we live in a Tinker Bell economy where, because everyone believes in the delusion of paper currency, it functions well. Much like the ancient mariners who met their ends voyaging out of the Mediterranean far beyond the Pillars of Hercules, Law’s scheme—a mass delusion gone bad—came to grief through lack of experience, but also spotlit the way to the future.

The Mississippi Company bubble infected the entire Continent. During its fever, the stodgy Venetians dropped their ancient opposition to joint-stock companies; a few were enthusiastically floated, then disappeared as news of the subsequent disaster in Paris seeped south. The Dutch, not to be outdone by the French, also followed suit with forty-four stock flotations, thirty of which more or less immediately doubled in price. In the less developed parts of Europe, trading companies sprouted like wildflowers and disappeared just as rapidly; fully 40 percent of eighteenth century European stock issuance occurred in the year 1720.200

The French bubble resonated loudest in London in the person of Sir John Blunt, a man born at precisely the right time. He struck out on his own at age twenty-five in 1689, the year of the settlement that followed the Glorious Revolution of 1688, in which the Dutch stadtholder, William III, invaded England at the invitation of its Protestant forces and ascended the throne as King William III and ended the Stuart monarchy.

Before that date, England had no “national debt,” only the financial obligations of the king and his family. When Charles II died in 1685, he, his brother, and his nephew owed about one million pounds sterling to London’s bankers, to whom they repaid not a farthing of interest or principal.201 Because of the ever-present threat of nonpayment of crown loans, bankers logically charged high rates, which stifled England’s economy. The settlement that followed the Glorious Revolution, in which the crown surrendered the divine right of kings for a secure tax base, had the immediate effect of making government debt more attractive. This, in turn, lowered interest rates more generally; with high returns no longer available from relatively safe bonds, investors sought opportunity in riskier ventures. This, in turn, kick-started a boom in joint-stock companies over the next decade.

Blunt, the son of a dissenter-Baptist shoemaker, apprenticed as a scrivener, a writer of legal and financial documents, an occupation that imparted insider knowledge of real estate and financial activities. Blunt nurtured this entrée into a small commercial empire that included a linen business and a company that supplied London with water. He then obtained employment with the most aggressive of the new joint-stock companies, Sword Blade.

Initially, the company manufactured advanced French-style rapiers, but it soon expanded into land speculation and the trading of government debt. (Radical changes in a business model are a feature of bubble-associated chicanery; nearly three centuries later, Enron would morph from a dull power plant and pipeline company into a futures-trading juggernaut before blowing up.)

In 1710, Blunt’s business acumen caught the eye of the chancellor of the exchequer, Robert Harley, who sought Blunt’s assistance with the nation’s massive debt, which, like France’s, was the legacy of the War of the Spanish Succession. Blunt indeed had an idea or two. His solution to the debt featured a speculative frisson that would become his trademark: the government would issue conventional 6 percent bonds that contained lottery tickets sporting prizes ranging from £20 up to a mind-boggling £12,000. The offering’s success led to an even more appealing scheme, “The Adventure of the Two Millions”: a complex, layered lottery based on £100 tickets, with five successive drawings and a top prize increasing with successive escalating tiers of £1,000, £3,000, £4,000, £5,000, and, finally, £20,000; with each drawing, the possibility of a yet larger payoff kept the losers in the game.

The success of these ventures emboldened Harley, who founded the South Sea Company in 1711 with the express purpose of taking over all of England’s considerable debt, with himself as governor and a board studded with Sword Blade hands, including Blunt.202 In exchange for assuming the government debt, the South Sea Company, like its older Parisian sister, the Mississippi Company, obtained a monopoly on trade with South America, despite the fact that Spain and Portugal controlled the continent and that nary one of the Company’s board had experience with the Spanish-American trade. Partially in exchange for this “monopoly,” the company assumed £10 million of government debt.

Ironically, although fear and envy of Law’s French system triggered the English South Sea Bubble, which occurred nearly simultaneously with the one in Paris, the Mississippi Company’s assumption of France’s national debt in 1717 was in fact modeled on South Sea’s previous assumption of England’s. For eight years after the Company’s 1711 chartering, the exchange of government debt for a “monopoly” on the New World trade was a relatively small-scale affair, but by 1720 the skyrocketing French Mississippi Company and the thousands mobbing Rue Quincampoix dazzled the English. Wrote Daniel Defoe from that Paris street in that year, as the French bubble blew the loudest:

You, Mr. Mist in England, You are a Parcel of dull, phlegmatic Fellows in London; you are not half so bright as we are in Paris, where we drink Burgundy and Sparkling Champaign. We have run up a Piece of refined Air, a meer Ignis fatuus [wisp] here, from a hundred to two thousand, and are now making a Dividend of forty per cent.203

Fearing that the Bourbons had devised a financial perpetual-motion machine that would overpower their island kingdom, the South Sea Company and Parliament devised a similar scheme, in which the company assumed a much larger share of the nation’s debts (around £31 million), mainly in the form of annuities. The holders of these debts, the annuitants, it was proposed, would voluntarily convert their government securities into the Company’s shares.

The annuities, of course, were held mainly by English citizens to whom they yielded income. The annuity holders had to be made an attractive offer to part with them, and the easiest way to do so was to stimulate their limbic systems by convincing them that the price of the Company’s stock was bound to rise.

The Company sold shares of varying complexity, typically, offering to purchase £100 of annuities from their owners for a single share of stock with a par value (at issuance) of £100. A high share price benefited the Company, since it enabled it to keep for itself a larger number of shares. If, for example, the share price rose to £200, the company only had to exchange half the number of the shares it would have at a price of £100, and could keep the other half; if the price rose to £1,000, as it did briefly, the company got to keep 90 percent of the shares held in its inventory. Further, as share prices rose, they became yet more desirable, a positive feedback loop that is the central feature of all bubbles.

Now, almost three centuries later, the nature of Blunt and Harley’s command of psychology becomes more clear. They had stumbled across a powerful way to exploit a very old human phenomenon: our species’ preference for “positively skewed outcomes”—ones with low-probability but enormous payoffs, even if the average of all payoffs is negative. No rational person, for example, spends $2.00 for a lottery ticket with a fifty-fifty chance of paying $3.00 or zero, since it produces a payoff of $1.50 (the average of zero and $3.00) for an average loss of 25 percent on the $2.00 ticket. Yet many people would buy a $2.00 ticket with a one-in-two-million chance of paying off $3 million, which carries the same average payout of $1.50 ($3,000,000/2,000,000) for the same average loss of 25 percent.204

In other words, Harley and Blunt had found a highway straight to the seat of human greed: the limbic system’s powerful reward-anticipation circuitry. The instincts that profited the prehistoric hunter-gatherer proved irresistible and deadly on the balance sheet.

As we now know, the South Sea’s monopoly was nearly worthless, but that did not prevent the company from floating the most fantastical rumors. Wrote Mackay:

Treaties between England and Spain were spoken of, whereby the latter was to grant a free trade to all her colonies; and the rich produce of the mines of Potosi-la-Paz was to be brought to England until silver should become almost as plentiful as iron. . . . The company of merchants trading to the South Seas would be the richest the world ever saw, and every hundred pounds invested in it would produce hundreds per annum to the stockholder.205

To assure Parliament’s assent to the scheme, the Company salted MPs with shares that appreciated after passage. The first share sales for cash took place on April 14, 1720, and the first conversions of annuities to shares took place two weeks later; the share price had already risen from £120 at the beginning of the year to around £300; by June, it had peaked above £1,000. The byzantine details of Blunt’s structure raised the earlier Adventure of the Two Millions to a new level: the Company deployed successive subscriptions of different share classes designed specifically to capture the public imagination. Finally, as already mentioned, the higher the share price, the fewer the number of shares the Company had to provide the holders of the government debt/annuities, thus leaving yet more shares in the hands of Blunt and his colleagues.206

Four features distinguished the English bubble from the French one. First, while the French bubble revolved almost completely around the shares of one company, the English one was associated with share flotation in other ventures encouraged by the general euphoria of the time; Mackay listed no fewer than eighty-six of these so-called bubble companies, and subsequent historians have identified about twice that many. While most aimed at solid ends, such as the building of roads and houses and establishing trade in imported goods, other schemes were fantastical: “for trading in hair,” “for a wheel of perpetual motion,” “for drying malt by hot air,” and “for the transmutation of quicksilver into a malleable fine metal.” Contemporary sources listed numerous others. Many were likely apocryphal, such as an air pump to the brain, or “to drain the Red Sea with a view to recovering the treasure abandoned by the Egyptians after the crossing of the Jews,” or, most famously of all, one “for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage; but nobody to know what it is.”207

The second distinctive feature of the South Sea Bubble was the extreme degree of leverage in the English bubble companies. Similar to the 15 percent down payment required for Mississippi Company shares, South Sea Company shares could be purchased with a down payment of only 10 to 20 percent, with the rest due in subsequent calls. The leverage of the bubble companies was higher than that of South Sea—that is, their initial subscription prices were lower; in one case, one shilling for a share of stock supposedly worth £1,000 (0.005 percent of the stated purchase price). Accordingly, bubble companies were so poorly funded that they generally flamed out rapidly. Nonetheless, a few were capitalized and managed well enough that they survived, among which were two insurance firms: London Assurance and Royal Exchange.

Shareholders had a giddy ride up, and the effect on the more general public was seductive. Wrote Mackay, “The public mind was in a state of unwholesome fermentation. Men were no longer satisfied with the slow but sure profits of cautious industry. The hope of boundless wealth for the morrow made them heedless and extravagant for today.”208

Early–eighteenth-century London could be imagined as two separate cities: to the west, the seat of government, Westminster, Parliament, St. James Palace, and Buckingham Palace, newly built for the Duke of Buckingham; and to the east, its mercantile center, the “City.” The latter’s beating heart was the Royal Exchange, where the capital’s merchant elite dealt in all manner of foreign and domestic commerce: wool, timber, grain, and a myriad of other goods.

The stock jobbers, despised by the mercantile hierarchy, were unwelcome in the Exchange’s halls and thus banished to a warren of coffeehouses that clustered in a tiny street sandwiched in the acute angle formed by Lombard Street and Cornhill, dubbed “Exchange Alley.”

Typically, the speculators lined up at the coffeehouses where the “financiers” hawked shares, usually acquired for the derisory initial subscription. The new owners then hurried down to nearby ’Change Alley to flip their shares to even greater fools through the good offices of the stock jobbers. During the late spring and summer of 1720, the scene was as manic as in Rue Quincampoix: hackney cabs were in short supply, and even when procured, were likely to be gridlocked in the narrow streets. Caffeinated traders packed coffeehouses like Jonathan’s, Garraway’s, and Sam’s, and pickpockets flourished; it was easier to find the king and his court in the alley than at the palace. The lawyer for a Dutch investor described the proceedings as “nothing so much as if all the Lunatics had escaped out of the madhouse at once.”209

As in Paris, the speculation nourished a general price inflation. King George I threw the most lavish birthday party the nation had seen, and company directors demolished their mansions to make way for yet larger ones. Throughout most of modern financial history, property prices have ranged between five and twenty times annual rental values; in 1720, London property sold for forty-five times yearly rents, a ratio later approached during the real estate bubble of the early 2000s.210 The South Sea enthusiasm also saw the birth of another characteristic feature of bubbles: securities speculations as a fashion statement. At the height of the action, London’s social scene shifted east from St. James’s Palace and Westminster to the City; there, a group of aristocratic ladies rented a shop just off ’Change Alley, where “at leisure times, while their agents are abroad, they game for china.”211 Nor was the excitement limited to the highborn:

Young Harlots too, from Drury-Lane,

Approach the ’Change in Coaches,

To fool away the gold they gain

By their obscene debauches212

Such an atmosphere was not conducive to rational decision-making. The speculation bubbled most intensely among the aristocracy. In June, near the peak, the worried chancellor of the exchequer, John Aislabie, advised King George to cash in his chips: £88,000 worth of Company stock. The famously rude monarch called his minister a coward, but Aislabie held his ground, and in the end George converted about 40 percent of his holdings into safe assets.213

The third distinctive feature of the South Sea Bubble was the growing hubris of its perpetrators; while John Law retained his inherent decency throughout the Mississippi episode, the same cannot be said of his English counterparts. While it’s easy to conceive of Blunt or Aislabie as either credulous or mendacious, these two adjectives are only a starting point. From their earliest histories, commercial societies equate riches with intelligence and rectitude; people of great wealth appreciate hearing of their superior brainpower and moral fiber. The wealth and adulation that accompany financial successes inevitably instill an overweening pride that corrodes self-awareness. Worse, great wealth not infrequently arises more from dishonesty than from intelligence and enterprise, in which case the adulation induces a malignancy of the soul, as indeed occurred to Blunt, who by this point had evolved into the archetype of the modern megalomaniacal CEO. An anonymous pamphlet, probably written just after his downfall, describes how, shortly before the South Sea Company imploded, he traveled to the newly fashionable resort of Tunbridge Wells: “In what splendid equipage [Blunt] went to the Wells, what respect was paid him there, with what haughtiness he behaved in that place, and how he and his family, when they spoke of the Scheme, called it our Scheme.”214 The pamphleteer painted the classic picture:

[Blunt] did never permit any body to make a motion in relation to [company transactions] but himself, during his first months reign; nor any minute, relating thereto, to be entered in the Court-Book, but what he dictated. He visibly affected a prophetic profile, delivering his words with an emphasis and extraordinary vehemence; and used to put himself into a commanding posture, rebuking those that durst in the least oppose any thing he said, and endeavouring to inculcate, as if what he spoke was by impulse, uttering these and such like expressions: Gentlemen, don’t be dismayed: you must act with firmness, with resolution, with courage. I tell you, ’tis not a common matter you have before you. The greatest thing in the world is referred to you. All the money of Europe will center amongst you. All the nations of the earth will bring you tributes.215

As pointed out by historian Edward Chancellor, bubbles, from South Sea to the internet, often evoke megalomania from their principals:

The plans of the great financier may act as a catalyst to a speculative mania, but the financier himself does not remain untouched by events. His ambition becomes limitless, a chasm opens up between the public appearance of success and universal adulation, on the one hand, and the private management of affairs which become increasingly confused and even fraudulent.216

Blunt engineered the manipulation of South Sea shares, including the loaning out of money from subscriptions for further stock purchases. He not only profited from the price increase before selling out most of his shares near the top, but also secretly issued himself, friends, and many MPs additional shares, some of which were fraudulent.

The end, as usually transpires, came from an unexpected direction. In June 1720, with one eye on the bubble companies’ drawing away of capital from South Sea and the other on the collapse of the share price of the Mississippi Company, Blunt had Parliament pass the Bubble Act just as South Sea share prices were peaking. The act required parliamentary approval for incorporation of new enterprises and restricted them to five shareholders; Blunt also had the courts prosecute three of the existing bubble companies for exceeding their charters.

As in Paris, Blunt’s megalomania rippled outward. Mackay wrote that one director, “in the full-blown pride of an ignorant rich man, had said that he would feed his horse upon gold.”217 It was also reflected in the general populace. “The overbearing insolence of ignorant men, who had arisen to sudden wealth by successful gambling, made men of true gentility of mind and manners blush that gold should have power to raise the unworthy in the scale of society.”218 Blunt’s actions against competing bubble companies boomeranged, pricking not only the bubble companies, but also his own South Sea; by late October, its share price had fallen to £210 from its peak of £1,000, and by the end of 1721, it had sunk below £150.219

The fourth, and final, difference between the South Sea and the Mississippi bubbles was their vision and scope. John Law was no ascetic, but neither did he focus exclusively on his own self-interest; he genuinely desired, through a revolutionary expansion of credit, to stimulate and advance France’s economy. Blunt’s scheme, on the other hand, channeled credit narrowly through the Company into his own pocket; when the credit expansion jumped the Company’s boundaries into other ventures, his efforts to curtail it succeeded all too well and so destroyed not only his targets but South Sea as well. The narrowness of Blunt’s scheme, from the national perspective, confined the relatively brief damage to the financial sector. This proved its saving grace, in distinction to the French catastrophic banking collapse, nationwide inflation, and subsequent long-lasting bank phobia.220

Figure 3-2. South Sea Share Prices 1719–1721

Also, unlike the Mississippi Company, South Sea was not a completely empty promise. Even in the early eighteenth century, a reasonable estimate of its intrinsic worth could be made. In the first place, it held the annuities tendered to it by the original annuitants, now company shareholders, and these assets had value amounting to, very roughly, £100 per share, approximately where it settled following the bubble’s collapse.

Another distinguishing feature of South Sea was that it had inherited the monopoly on the slave trade in Spain’s colonies (the asiento) granted to Queen Anne in 1707, which made up the lion’s share of its supposed business volume, which by treaty with Spain virtually excluded New World products, limited to an “annual ship” containing five hundred tons of goods. The Company’s New World trade was, however, nearly worthless, since its expertise lay in finance, and not international commerce; damningly, one of the directors was caught red-handed using sixty of the Company’s five-hundred-ton annual allowance for his own benefit. By 1714, six years before the bubble collapsed, the Company’s actual trade business was unprofitable, and the company withdrew from it; forty years later, it sold its asiento rights for a mere £100,000.221 In the end, the value of the Company’s New World ventures was beside the point; speculators cared not about the profits from the trade in slaves or sugar, but those from the buying and selling of shares whose prices seemed to grow to the sky.

Probably the most sophisticated contemporary calculations of share price were made by a barrister and MP named Archibald Hutcheson, who published a long series of reports on the Company’s shares. Fortuitously, one was written in June 1720, just before the peak of the boom; it suggested a higher market value, £200, twice that calculated from the value of the company’s annuity assets. At that point, the share price was £740; he predicted that “the present reigning madness should happen to cease.” In the event, the madness went on a few more months; in July, at a prevailing price of £1,000 per share, Hutcheson reckoned that the total value of the company was nearly twice the value of all the land in England.222 (This situation was echoed by the 1980s Tokyo real estate bubble, in which the hypothetical value of the Imperial Palace grounds exceeded that of all the land in California.)223

The next year, motivated not only by aggrieved constituents but also by its own swindled MPs, Parliament investigated the share price collapse and the massive wealth accumulated by Blunt, his colleagues, and government insiders. It settled on Chancellor Aislabie as scapegoat, forced his resignation, sent him to the Tower, and expelled six other MPs. The South Sea Company itself continued to function until 1853, not as a trading firm, but simply as a holder of government debt. The king, although the object of popular derision, avoided sanction.224

Some spoke of jailing or even hanging the company’s directors, a fate they narrowly avoided after a brief imprisonment. Rather, Parliament confiscated their estates to compensate the scheme’s victims; it allowed Blunt to keep £5,000 of his £187,000 in assets, and he retired in obscurity to Bath, founding a distinguished lineage of pious descendants that included a bishop and Queen Victoria’s chaplain.225

The Bubble Act, passed at the height of the mania, which had not only put a brake on further speculative enterprises but also inadvertently helped sink South Sea, remained on the books for more than a century. Inevitably, memories of the frenzy and its collapse would fade and the market’s animal spirits, buoyed by an exciting new technology and easy credit, and stoked by its promoters, the public, press, and politicians, would rise again, and so yield a wave of manias that would dwarf those of the early eighteenth century.

162. William Harrison Ainsworth, The South Sea Bubble (Leipzig: Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1868), 48–49.

163. During the late medieval period, bills of exchange also expanded credit. For a lucid description of how the modern system works, see Frederick Lewis Allen, The Lords of Creation (Chicago: Quadrangle Paperbacks, 1966), 305–306; and Antoin Murphy, John Law (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), 14–16.

164. Montgomery Hyde, John Law (London, W. H. Allen: 1969), 9.

165. Hyde, 10–14; see also Malcolm Balen, The Secret History of the South Sea Bubble (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), 14. For a detailed account of the machinations surrounding his duel with Wilson and ultimate escape, see Antoin Murphy, John Law (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), 24–34.

166. Murphy, 38.

167. Quoted in Murphy, 38.

168. Murphy, 37–40.

169. Ibid., 37.

170. Walter Bagehot, Lombard Street (New York: Scribner, Armstrong & Co., 1873), 2–5.

171. Joan Sweeney and Richard James Sweeney, “Monetary Theory and the Great Capitol Hill Baby Sitting Co-op Crisis,” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking Vol. 9, No. 1 (February 1977): 86–89. Also see Paul Krugman, “Baby Sitting the Economy,” http://www.pkarchive.org/theory/baby.html, accessed April 28, 2017.

172. William Potter, The Key of Wealth (London: “Printed by R.A.,” 1650), 56. For “barbarous relic,” see John Maynard Keynes, A Tract on Monetary Reform (London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1924), 172.

173. John Law, Money and Trade Considered (London: R. & A. Foulis, 1750), 8–14.

174. John Law, Essay on a Land Bank, Antoin E. Murphy, Ed. (Dublin: Aeon Publishing, 1994), 67–69.

175. Law, Money and Trade Considered, 188.

176. Quoted in Murphy, 93. For a detailed discussion of barter versus the mutual exchange of favors, see David Graeber, Debt (New York: Melville House, 2012).

177. Quoted in Murphy, 93, italics Murphy’s.

178. Quoted in Murphy, 92.

179. Law, 182–190, quote 190.

180. Hyde, 52–63, Murphy 45–75.

181. Quoted in Murphy, 125.

182. Hyde, 89–90.

183. Murphy, 157–162.

184. In 1717 Law was granted permission to rename it the Company of the West, and in 1719 it was merged with the China Company and renamed the Company of the Indies, but hereafter will be referred to by its original name, the one by which it is known to history: the Mississippi Company.

185. Ibid., 162–183.

186. Hyde, 115; and Murphy, 189–191. The share structure of the company was dizzyingly complex, with several offerings through 1720 and three major share classes, whose ownership rights interlocked; see Murphy 165–166.

187. Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions, I:25–26.

188. Ibid., I:30.

189. Letters of Madame Charlotte Elizabeth de Baviére, Duchess of Orleans, ii:274, https://archive.org/stream/lettersofmadamec02orluoft/lettersofmadamec02orluoft_djvu.txt, accessed October 31, 2015.

190. Murphy, 205.

191. In 1700, Paris’s population was 600,000; see http://www.demographia.com/dm-par90.htm. The Duchess of Orleans estimates that about half that number moved to the city during the boom; see Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Delusions, I:40; and Murphy, 213.

192. Murphy, 207.

193. For the precise mechanisms of the scheme’s unwinding and the Byzantine politics behind them, see Murphy, 244–311; for the system’s serial inflation-adjusted (silver) values, see Table 19.2, 306.

194. Larry Neal, I Am Not the Master of Events (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 55–93.

195. Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions, I:40; Hyde, 139–210; Murphy, 219–223, 312–333.

196. John Cuevas, Cat Island (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2011), 11.

197. Ibid., 10–12.

198. William Lee, Daniel Defoe: His Life, and Recently Discovered Writings (London: John Camden Hotten, Piccadilly, 1869), II:189.

199. Barry Eichengreen, Golden Fetters (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

200. Stefano Condorelli, “The 1719 stock euphoria: a pan-European perspective,” working paper, 2016, https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/68652/, accessed April 27, 2016.

201. John Carswell, The South Sea Bubble (Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton Publishing, Ltd., 2001), 19.

202. Balen, 23–32. Blunt presented the Company to Parliament in the spring of that year, which approved its charter that fall, subsequent to which Queen Anne awarded the actual charter (personal communication, Andrew Odlyzko).

203. Lee/Defoe, II:180.

204. For a lucid exposition of this phenomenon, see Antti Ilmanen, “Do Financial Markets Reward Buying or Selling Insurance and Lottery Tickets?,” Financial Analysts Journal Vol. 68, No. 5 (September/October 2012): 26–36. The Kansas state lottery is a good example of the positive skewness/poor payoff phenomenon; see the table in http://www.kslottery.com/games/PWBLOddsDescription.aspx. If one assumes a $100 million payoff for the Powerball, the total expected payout on a single $2 ticket is 66 cents, or 33 cents on the dollar—that is, a loss of 67 percent.

205. Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions, I:82.

206. For those interested in the exact mechanisms of both Law’s and Blunt’s schemes, see Carswell, 82–143; and Edward Chancellor, Devil Take the Hindmost (New York: Plume, 2000). On the dates of share purchases and conversions, Andrew Odlyzko, personal communication.

207. Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions, I:92–100. In the opinion of Andrew Odlyzko, there is some documentary evidence behind a company “for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage; but nobody to know what it is” (Odlyzko, personal communication).

208. Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions, I:112; A. Andréadès, History of the Bank of England (London: P.S. King & Son, 1909), n250.

209. Dale, 111–112; Carswell, 128; Balen, 94; quote Kindleberger, 122.

210. Carswell, 131.

211. Ibid., 116.

212. Anonymous, The South Sea Bubble (London, Thomas Boys, 1825), 113.

213. Carswell, 131–132, 189, 222.

214. Anonymous, “The Secret History of the South Sea Scheme,” in A Collection of Several Pieces of Mr. John Toland (London: J. Peele, 1726), 431.

215. Ibid., 442–443.

216. Chancellor, 74.

217. Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions, I:112–113.

218. Ibid., I:112.

219. Larry Neal, The Rise of Financial Capitalism (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 234. The actual price at the bottom was £100, but this included a 33.3 percent stock dividend, so £150 is closer to the truth (personal communication, Andrew Odlyzko).

220. Carswell, 120; Kindleberger, 208–209.

221. See Helen Paul, The South Sea Bubble (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2011), 1, 39–42, 59–65. Ms. Paul belongs in the “rational bubble” camp of revisionist modern economic historians who postulate rational behavior during market enthusiasms. Beyond figures on slave offloadings and mentions of experienced slave traders who were connected to the company, there seemed to be no financial data to support the asiento as a source of cash flow large enough to justify South Sea’s mid-1720 share price; see Carswell, 55–57, 240. A more nuanced modern evaluation of South Sea’s intrinsic worth concluded that given the possibility, albeit unrealized, of huge profits, no reasonable estimate could be made; Paul Harrison, “Rational Equity Valuation at the Time of the South Sea Bubble,” History of Political Economy Vol. 33, No. 2 (Summer 2001): 269–281.

222. The mechanics of South Sea’s debt conversions and flotations are highly complex, and well beyond the scope of this volume. For an authoritative description of these, see Richard Dale, The First Crash (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 102–122. For Hutcheson’s calculations, see 113–117, quote 114.

223. Ian Cowie, “Oriental risks and rewards for optimistic occidentals,” The Daily Telegraph, August 7, 2004.

224. George I was an accidental king; when his second cousin Queen Anne died in 1714, he was no better than fiftieth in the line of succession, and ascended to the throne only because the 1701 Act of Settlement forbade a Catholic monarch and so disqualified all those ahead of him. Upon his ascension to the throne, the prime minister became the nation’s de facto leader.

225. Carswell, 221–259. On the brief imprisonments, Andrew Odlyzko, personal communication.