APPENDIX

The Ghost in Bleak House

AM I THE ONLY ONE WHO THINKS HE'S SEEN THE GHOST IN Bleak House? I mean the ghost whose story Mrs. Rouncewell tells in chapter 7 and whose footsteps echo across the Ghost's Walk terrace at Chesney Wold. So far as I know, no one else has ever claimed to see the ghost—no reader or critic, no character in the novel, not even the unnamed present-tense narrator. People hear the ghost, or what they take to be the sound of its steps on the terrace, drip, drip, drip; but no one sees the ghost. I do.

My friend Bob Newsom, a distinguished Dickensian and expert reader of Bleak House, insists that I'm hallucinating. What I read as “ghost,” Bob says is merely shadow. But he tells me not to worry. Bleak House does this sort of thing to people, he says, excites their imagination, plays tricks on the eye and ear, makes them see things that aren't there, shadows that move, optical illusions. If I really want to explain myself, Bob continues, all I need to do is tell my story, how I first thought I saw a ghost, but then came to realize the error of my ways. I can then chalk the whole experience up to “the Bleak House effect,” the novel's way of luring its characters (and its readers) to imagine things that might have been but never were or that exist only in their minds.

Bob may be right. I may be like Esther Summerson when she first sees Lady Dedlock in the church and suddenly has visions of her godmother and her own younger self; or like Mrs. Snagsby, projecting her suspicions onto every new bit of information and inventing evidence to fit her suspicions; or like Mr. Guppy in chapter 33. When the servant leaves him in the dimly lit library of the house in town for his first interview with Lady Dedlock, “Mr. Guppy looks into the shade in all directions, discovering everywhere a certain charred and whitened little heap of coal or wood. Presently he hears a rustling. Is it—? No, it's no ghost; but fair flesh and blood, most brilliantly dressed” (533). As Guppy waits for his appointment, the burnt remains of Krook linger in his memory, but it is Lady Dedlock herself, not a ghost, who appears out of the shadows. Although I've witnessed no recent scenes of spontaneous combustion, “my” ghost may be something similar—the product of an overactive imagination, wishful thinking, or something I ate. But I'm not easily dissuaded. I know the ghost is there. I still see it, and I think others do too. They just don't recognize it. You decide.

When I say I see the ghost, I mean I see it in one of the novel's illustrations: “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold” (see fig. 9 on p. 81). The figure I identify as the ghost is standing (or hovering) in front of the mausoleum door on the viewer's right-hand side, just inside the fence that surrounds the vault and immediately to the left of the piece of statuary that guards the entrance to the plot. Darker than the surrounding area, but not so dark as the shadow just above it cast by the curved balustrade that leads up to the mausoleum door, the figure is nevertheless transparent. Behind and through it, the surface of the door is visible. Roughly triangular in shape and slightly wider as it nears the ground, the figure is surmounted by a small oval, lighter in color, that I read as its face, though no features are discernible. The “face” may be covered by a veil. The figure's “body” is draped in something that resembles a long, loose-fitting gown or cloak of the sort worn out of doors by Lady Dedlock and Esther in the novel's other illustrations. This “gown” could also be a sheet or shroud. Judging from this “garment,” I would say the figure is a woman. Judging by the door behind it, I would say the figure is of an appropriate human size and scale.

Why has no one ever commented on the strange figure—or, if you prefer, the ambiguous patch of darkness—that I read as a ghost? One reason is that many modern editions of the novel either do not contain a full set of the original Hablot K. Browne (“Phiz”) illustrations or else have reproductions of poor quality. To see the ghost, you need a good edition, and you need to know where to look. Another reason readers have not recognized the ghost is that the verbal text makes no mention of one. “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold” corresponds to a passage near the beginning of chapter 66 in the novel's final double monthly number. The passage in question describes Lady Dedlock's final resting place in the Dedlock family mausoleum and, in particular, the regular visits faithfully paid by Sir Leicester to the site of his wife's grave. Here is the passage.

Up from among the fern in the hollow, and winding by the bridle-road among the trees, comes sometimes to this lonely spot the sound of horses' hoofs. Then may be seen Sir Leicester—invalided, bent, and almost blind, but of a worthy presence yet—riding with a stalwart man beside him, constant to his bridle-rein. When they come to a certain spot before the mausoleum door, Sir Leicester's accustomed horse stops of his own accord, and Sir Leicester, pulling off his hat, is still for a few moments before they ride away. (981)

Told by the unnamed present-tense narrator, this brief paragraph moves in three sentences from a slightly spooky evocation of approaching sound to a description of the two visitors, Sir Leicester and the stalwart George, to their halt at a particular spot before the mausoleum, and finally to their departure.

There's no ghost in this passage, right? Just Sir Leicester and George Rouncewell. But wait—the passage contains two details that are worth another look: the mausoleum door and Sir Leicester's failing eyesight. If there were anyone or anything in front of the door, it might well escape Sir Leicester's notice, since he is “almost blind.” Is it possible that the text is telling us to look for something that Sir Leicester does not see and to look for it in the vicinity of the door?

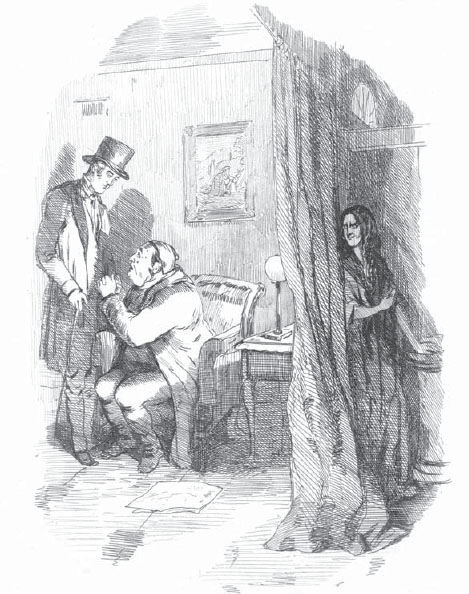

Readers of illustrated novels—and this includes most literary critics—tend to privilege the verbal text. They regard illustrations as secondary, as the transposition into visual terms of words on the page. Such readers seldom stop to consider the possibility that a visual image might have priority, might tell us something that the words omit or only suggest, or, alternatively, that verbal text and illustration may tell conflicting stories. In this connection, it is useful to recall an illustration from the final chapter of Thackeray's Vanity Fair (1847-48). In “Becky's second appearance in the character of Clytemnestra,” the figure of Becky Sharp, holding what might be a dagger or perhaps a vial of poison, appears, heavily shaded, hidden behind a curtain and looking out at a helpless Jos Sedley (fig. 11). Although Becky had taken the part of Clytemnestra during the charades enacted earlier in the novel, there is no mention in the verbal text of any second appearance by her in this role. Text and image tell different stories. If we privilege the verbal text, then the image may be an illusion, Jos's hallucination or a trap set for the suspicious reader who wants to think the worst of Becky. If we privilege the illustration, Becky is a murderess. In either case, the image of Becky behind the curtain, looking sinister, is unquestionably there and is confirmed by the illustration's caption, whereas the presence of a figure of any sort in the illustration from Bleak House remains in doubt. Did Browne know the Thackeray illustration? Probably. Was he doing something similar at the end of Bleak House? Perhaps. Did Dickens have anything to do with it? We don't know.

“The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold” is one of four illustrations that Browne executed for the final double monthly number of Bleak House, dated September 1853. Of the other three images, two were meant for the novel's front matter when it was eventually published in volume form: the frontispiece (a dark plate of Chesney Wold) and the vignette title page (an image of Jo the crossing sweeper). The third image corresponds to a passage in chapter 64 and shows Mr. Guppy's second proposal to Esther. “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold” corresponds to a passage in the novel's penultimate chapter, “Down in Lincolnshire.” It is thus the novel's final illustration, or at least the one that accompanies the passage closest to the end of the novel's verbal text. As such, it occupies an important position in the sequence of illustrations and can be taken, in a certain sense, as part of the novel's ending—the final visual image with which the reader is left.

In a letter to Browne, dated June 29, 1853, and mailed from Boulogne, where he had gone to finish the last two monthly numbers of Bleak House, Dickens wrote to say that he would soon be sending his directions for the final four illustrations of the novel. “I am now ready with four subjects for the concluding double No. and will post them to you tomorrow or next day!!!!!!!!!!!!” (Letters 7: 107). Regrettably, the subsequent letter containing those instructions has not survived; we therefore have no information about Dickens's wishes in this respect, other than the fact that he did have such wishes and presumably communicated them to Browne. But what about Browne? What do we know or what can we surmise about his intentions?

FIG. 11. William Makepeace Thackeray, “Beck's second appearance in the character of Clytemnestra,” etching from Vanity Fair: A Novel Without A Hero, 1848. (Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries)

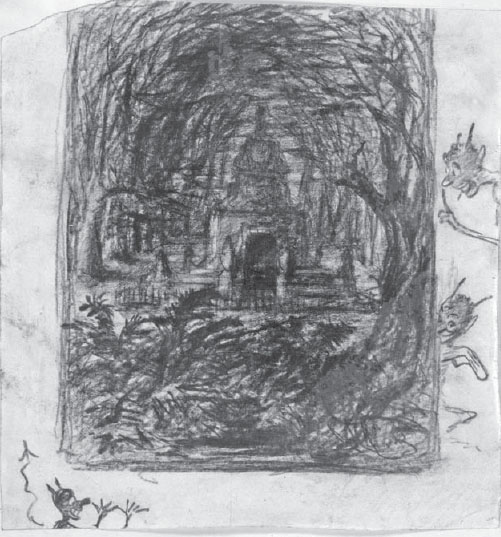

The only evidence of Browne's plans, aside from the final illustration itself, is to be found in two drawings, one in the Free Library of Philadelphia (in the Elkins collection) and the other in the Beinecke Library at Yale (in the Gimbel collection). Both are of interest, though neither settles the question of whether Browne (and/or Dickens) meant there to be a ghost in the final illustration.

The Elkins drawing (fig. 12) is what Michael Steig calls a “working drawing.”1 That is, it is the drawing that Browne used in order to transfer the image from paper to the steel plate prior to etching. As such, the drawing is a mirror image of the final illustration. Browne would place a tracing of the drawing face down over the waxed plate, pass the plate through the press so that the marks of the drawing were transferred to the ground, remove the paper, and complete the image directly on the plate using his needle.2 He would then bathe the plate in an acid solution, allowing the acid to eat into the plate where the lines were drawn. The resulting plate could then be inked and used to print the final illustration.

In the Elkins drawing, the place where my ghost should appear is on the left-hand side; when printed, this becomes the viewer's right. I would very much like to say that I see a figure there, but the most I can claim is that the space is somewhat blurry, especially in comparison to the opposite side, where the door panels are clearly visible and nothing blocks our view. The Elkins drawing contains another curious feature, however. Three little demons or goblin-like figures appear in its margins. One thumbs his nose, another smirks and holds a curved pipelike object in his hand, and a third peers intently into the center of the image. The technical term for such marginal figures is “remarques.” What are we to make of them?

Steig, Jane R. Cohen, and Valerie Browne Lester all mention these demons and suggest that they reveal something about Browne's attitude toward Dickens, a mocking independence perhaps.3 My own suggestion is that the demons hint at the presence of other spirits and that the demon on the upper right, the one with the bulging eyes, is staring at something that Sir Leicester, whose viewpoint the illustration presumably represents, cannot see. A mausoleum, after all, is a logical place for ghosts to appear, and if humans cannot see them, perhaps other spirits can. We know that Chesney Wold is supposed to have a family ghost and that characters hear what they think are its footsteps on the terrace. If a ghost haunts the house (and if other ghostly figures, such as Volumnia and even Esther, do so at various points in the novel), why should a ghost not also appear at the spot where Lady Dedlock is buried?

FIG. 12. Hablot K. Browne, “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold,” working drawing, Bleak House, 1853. (Used by permission of the Rare Book Department, Free Library of Philadelphia)

The Gimbel drawing (fig. 13) complicates these speculations. Unlike the Elkins drawing, it is not a mirror image of the final illustration. As such, it may be what Steig calls a “preliminary sketch,” one that Browne produced in advance of making the plate as a guide for himself to what the final image would look like when it appeared in the novel. More likely, in view of the drawing's high degree of finish (which in turn suggests a more leisurely composition than the short turnaround time needed to complete four plates for the final number would have allowed), it is a subsequent, extra-illustrated drawing, one that Browne produced after the novel was published to use as a gift or as a record for himself or to sell to a collector. Signed “Phiz” in the lower left-hand corner and with the notation “BH” in the upper left, this drawing is much more finished than the Elkins image. Done in two different colors of ink and heightened with a white wash to suggest the reflection of light on the surface of the mausoleum, this drawing recalls similar fancy extra-illustrations that Browne produced after the fact from plates he made for other novels.

In any event, whether executed before the Elkins sketch or after Browne's final etching for the novel was complete, the Gimbel drawing does not support my “ghost” hypothesis. No figure stands before the mausoleum door. The blurry space in the Elkins sketch is gone. In the Gimbel drawing, that space is unambiguously vacant. Moreover, and somewhat curiously, there is no trace of the shadows that appear in the final image. Despite these facts, the Gimbel drawing does not prove conclusively—beyond the shadow of a doubt, I am tempted to say—that no ghost is present in the final illustration. Browne could have added the ghost at the last minute, directly onto the plate. Steig argues that Browne made such changes in other illustrations, adding details that do not appear in the working drawings and even sometimes reversing the direction in which a figure faces.4 In order to confirm or disprove the presence of my “ghost,” we must return to the final illustration as it appears in a good first edition of the novel.

Finding a “good first edition” of Bleak House is not as easy as it might at first appear. Illustrations in the original serial parts vary tremendously in quality. As more copies of the parts were printed, the plates from which the illustrations were taken began to wear, and the images themselves deteriorated accordingly.5 Another difficulty arises from differences in inking between one impression and the next. More heavily inked plates produce darker images, with a resulting loss of clarity and sharpness of detail. Moreover, at a certain point, the novel's publishers, Bradbury and Evans, began printing Browne's images using lithography, a technique in which the original designs were copied onto stone with a greasy material, allowing printed impressions to be taken from them. In an undated letter to Dickens, Browne complained of the ruinous effect that lithography had on his plates for Bleak House. “I am told,” he writes, “that from 15 to 25,000 [copies] are monthly printed from lithographic transfers—some of these impressions, when the etching is light and sketchy, will pass muster with the uninitiated—but, the more elaborate the etching—the more villainous the transfer.”6 The “villainous” effect of lithographic transfers may have affected some of the novel's “dark plates,” of which “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold” is an example.7 Whether the result of wear, poor inking, or lithography, fine details in the plates are often lost. In some monthly parts of Bleak House, the space in front of the mausoleum door becomes entirely black, and the shadows cast by the entrance balustrade, along with any figure that might be there, are swallowed up in undifferentiated inky darkness (fig. 14).

FIG. 13. Hablot K. Browne, “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold,” drawing, Bleak House, 1853? (Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

A different problem appears in some later editions of the novel, such as the Nonesuch.8 These editions use worn (or in some cases, perhaps retouched) plates, with the result that the shape I read as a ghost appears not as a patch of darkness, but as a lighter figure that stands out against a darker background (fig. 15). The result is an even more “ghostly” effect, since the figure now seems to possess the more conventional attributes of a phantom: an eerie glow and even greater transparency. Although striking in appearance—and providing evidence, some might argue, for the existence of an earlier figure occupying this position and of which it is the trace—this “ghost” may be the misleading result of a worn or reworked plate, since in the earliest impressions the “figure,” if it exists, should be dark.

It is also possible that the ambiguous patch of darkness I identify as “ghost” may be an artifact of reprinting, an effect of mechanical reproduction rather than part of Browne's original design. While it would certainly be gratifying to know what Browne (and Dickens) intended in this regard, from another perspective their “authorial” intention ultimately matters less than the fact that some copies of the original serial parts do contain the shadowy presence that resembles a human figure. I confess that I take a certain pleasure in the thought that some copies contain this shadow or figure and some do not. It is often the way of ghosts to come and go mysteriously. Moreover, they do not appear to everyone.

FIG. 14. Hablot K. Browne, “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold,” lithographic transfer?, Bleak House, 1853, first bound edition.(Author's personal collection)

“The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold” and the accompanying passage from chapter 66 recall the conclusion to another Dickens novel, one in which the prospect of ghostly visitation is explicitly mentioned. The final paragraph of Oliver Twist describes the visit to a village church where a marble tablet bearing the name “Agnes” commemorates Oliver's dead mother. Although the church contains no coffin and no corpse, the narrative voice suggests that the spirit of Agnes will return to visit that spot.

FIG. 15. Hablot K. Browne, “The Mausoleum at Chesney Wold,” etching from Bleak House, 1938 ed. (rpt. 2005, Nonesuch edition). (Used by permission of Duckworth Publishers)

Within the altar of the old village church, there stands a white marble tablet, which bears as yet but one word,—'Agnes!' There is no coffin in that tomb; and may it be many, many years, before another name is placed above it! But, if the spirits of the Dead ever come back to earth, to visit spots hallowed by the love—the love beyond the grave—of those whom they knew in life, I believe that the shade of Agnes sometimes hovers round that solemn nook.9

The accompanying illustration by Cruikshank shows Oliver and Rose Maylie standing inside the church and looking at the tablet (fig. 16). There is no hint of a ghost in the illustration, but the novel's final paragraph invites the reader/viewer to imagine one “hovering” nearby. Is it possible that when he wrote the story of another illegitimate child who yearns for the presence of a mother who dies, a story in which ghosts and ghostly presences abound, Dickens may have reverted to the idea with which his earlier novel ended and instructed his illustrator to suggest the presence of a “shade” lingering near the site where the mother is buried?

FIG. 16. George Cruikshank, “Rose Maylie and Oliver,” etching from Oliver Twist, 1838. (Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries)

In their study of first editions of Dickens's novels, Thomas Hatton and Arthur Cleaver report having examined a thousand sets of original serial parts of Bleak House. In my research, I have consulted only a dozen, yet among these I can report considerable variation in the quality of the mausoleum illustration. Of the examples I have seen, and in support of my contention that some of them contain the figure of a ghost, I have selected and reproduced here as figure 9 the impression that I consider the best in terms of its overall clarity and sharpness of line. I see a shade. Bob sees only shadow. What do you see?