The difference between what we are doing and what we’re capable of doing would solve most of the world’s problems.

MAHATMA GANDHI

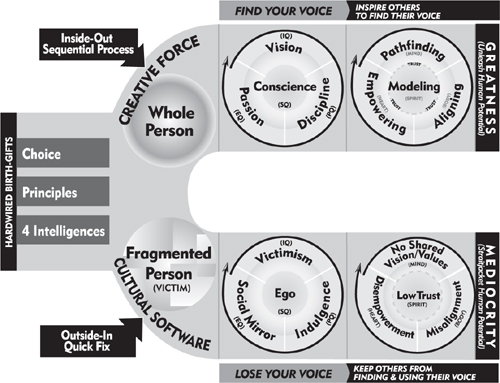

THE 8TH HABIT—Find Your Voice and Inspire Others to Find Theirs—is an idea whose time has come. “Whose time has come” is a phrase from the famous line by Victor Hugo quoted earlier: “There is nothing so powerful as an idea whose time has come.” The reason why the 8th Habit is such an idea is that it embodies an understanding of the whole person—an understanding that gives its possessors the key to crack open the limitless potential of the knowledge worker economy. As is represented on the lower road of figure 14.1, the Industrial Age manual worker economy was based on a part- or fragmented-person paradigm. In today’s world, this lower road leads to mediocrity at best. It literally straitjackets human potential. Organizations mired in the mind-set of the Industrial Age continue to have the people at the top making all the important decisions and have the rest “wielding screwdrivers.” What an enormous waste! What an enormous loss!

Remember again the statement by author John Gardner: “Most ailing organizations have developed a functional blindness to their own defects. They are not suffering because they cannot resolve their problems but because they cannot see their problems.” This is exactly what has happened.

The 8th Habit gives you a mind-set and a skill-set to constantly look for the potential in people. It’s the kind of leadership that communicates to people their worth and potential so clearly they come to see it in themselves. To do this, we must listen to people. We must involve and continually affirm them by our words and through all 4 Roles of Leadership.

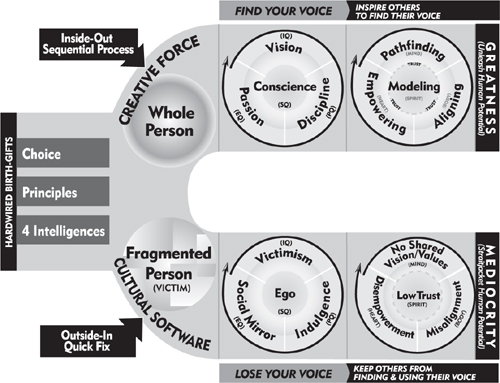

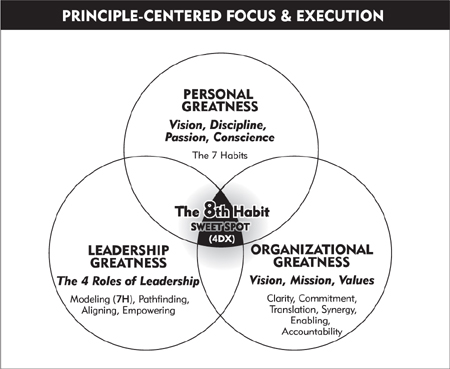

Here is a succinct way to remember what each role does. Notice how each role directly or indirectly affirms people’s worth as whole people and empowers the unleashing of their potential.

First, modeling (individual, team). Modeling inspires trust without expecting it. When people live by the principles embodied in the 8th Habit, trust, the glue of life, flourishes; trust comes only through trustworthiness. In short, modeling produces personal moral authority.

Second, pathfinding. Pathfinding creates order without demanding it. That means when people identify and are involved in the strategic decisions, particularly on values and high-priority goals, they emotionally connect; the locus of both management and motivation goes from the outside to the inside. Pathfinding produces visionary moral authority.

Third, aligning. Aligning structures, systems and processes is a form of nourishing the body politic and the spirit of trust, vision and empowerment. Aligning produces institutionalized moral authority.

Fourth, empowering. Empowering is the fruit of the other three roles—modeling, pathfinding and aligning. It unleashes human potential without external motivation. Empowering produces cultural moral authority.

Remember, the most important modeling is done by the leader when he or she models the other three roles. In other words, pathfinding is modeling the courage to determine a course and the humility and mutual respect to involve others in deciding what matters most. Aligning is modeling the willingness to set up structures, systems and processes that are congruent with the “what matters most” strategic decisions so that the organization stays constantly focused on its highest-priority goals. Empowering is modeling a bone-deep belief in people’s capacity to choose and in the four parts of their nature through co-missioning processes.

I suggest that all that we have covered can be essentially summarized in two words: Focus and Execution. In these two words we truly find “simplicity on the far side of complexity.” Again, focus deals with what matters most, and execution deals with making it happen. The cutting-edge bestseller business book by Ram Charan and Larry Bossidy called Execution: The Discipline of Getting Things Done has been influential in my thinking behind this two-word summary.

The first two roles of leadership—modeling and pathfinding—can be summarized in one word: focus. The next two roles of leadership—aligning and empowering—can be summarized in one word: execution. How is this so? Think about it. Pathfinding is essentially strategic work; it’s deciding what the higher-priority goals are—what values are to serve as guidelines in accomplishing and sustaining those goals. But this requires both a clear understanding and a commitment in the culture toward these goals. Such commitment is based upon trust, trustworthiness and synergy—the essence of modeling. Only when there is true personal and interpersonal trustworthiness will trust develop and team synergy be effective. This personal/interpersonal modeling involves mutual respect, mutual understanding and creative cooperation (Habits 4, 5 and 6) in producing a clear, committed set of high-priority goals (Habit 2: Begin With the End in Mind). This personal/interpersonal trustworthiness is in turn based on people living true to their values and goals—in other words, personal focus and execution. This is Habit 3: Put First Things First. The expression “first things first” is another way of describing focus and execution.

The next two roles of leadership, aligning and empowering, represent the execution. This means creating structures, systems and processes (aligning) that intentionally enable individuals and teams to translate the organization’s larger “line-of-sight” strategic goals or critical priorities (pathfinding) into their actual day-to-day work and team goals. In short, people are empowered to get the job done.

Focus and execution are inseparably connected. In other words, until you have people on the same page, they will not execute consistently. If you use the Industrial Age command-and-control transaction model to get focus, you won’t be able to use the Knowledge Worker Age empowering transformation model to get execution—simply because without involvement and/or identification, you will not get emotional commitment to the focus. Execution will simply not take place. Likewise, if you use a knowledge worker/involvement/empowerment approach to achieve a common focus, but then an Industrial Age/command-and-control approach for execution, you won’t be able to maintain the focus because people will perceive the lack of sincerity and integrity.

On the other hand, if you use the Knowledge Age model on both focus (modeling, pathfinding) and execution (aligning, empowering), you will produce integrity and trustworthiness in the organizational culture. The organization will not only find its voice but it will also use its voice to superbly serve its purposes and stakeholders.

Early in the book I made the statement, “To know and not to do is really not to know.” This is a profound truth. The principles encompassed in the 8th Habit are of little worth until they, by practice and execution, become part of our character and skill-set—until they become a habit.

Execution is the great unaddressed issue in most organizations today. It is one thing to have clear strategy; it is quite another to actually implement and realize the strategy, to execute. In fact, most leaders would agree that they’d be better off having an average strategy with superb execution than a superb strategy with poor execution. Those who execute always have the upper hand. As Louis V. Gerstner, Jr., put it, “All of the great companies in the world out-execute their competitors day in and day out in the marketplace, in their manufacturing plants, in their logistics, in their inventory turns—in just about everything they do. Rarely do great companies have a proprietary position that insulates them from the constant hand-to-hand combat of competition.”2

There are many things that effect execution, but our xQ research shows that there are six core drivers to execution in an organization: clarity, commitment, translation, enabling, synergy and accountability. It follows, then, that breakdowns in execution typically occur as failures in one or more of these six drivers. We call them execution gaps:

• Clarity—people don’t clearly know what the goals or priorities of their team or organization are;

• Commitment—people don’t buy into the goals;

• Translation—people don’t know what they individually need to do to help the team or organization achieve its goals;

• Enabling—people don’t have the proper structure, systems or freedom to do their jobs well;

• Synergy—people don’t get along or work together well; and

• Accountability—people don’t regularly hold each other accountable.

The following chart (table 6) identifies these six execution gaps/drivers and gives a very simplified explanation of how the controlling Industrial Age mind-set literally causes these gaps and how the Knowledge Worker/whole-person model, which embodies the 8th Habit, can solve them.

1. Clarity: The manual worker/Industrial Age approach is simply to announce what the mission, vision, values and high-priority goals are. As we’ve discussed, these are often the product of top people going to off-site mission statement workshops and then returning to the workforce to announce in smooth language the strategic decisions to guide all other decisions in the organization. Over time, these mission statements become nothing more than PR statements, simply because there is no real involvement; therefore, there is no real identification, which is the essence of the Knowledge Worker Age. Remember that identification is personal moral authority coming from involvement with the admired person, not necessarily from involvement in the strategic decisions.

2. Commitment: The Industrial Age approach to getting commitment is to sell—communicate it constantly and frequently, explain it, and try to make sense of it. Sell, sell, sell! But research data show that only one in five have a passionate commitment to the high-priority goals of their team and organization. The 8th Habit approach in the Knowledge Worker Age is to put a whole person in a whole job—body, mind, heart and spirit. Pay me fairly, treat me kindly and respectfully, use my mind creatively in doing work that truly adds value and in doing it in a principle-centered way. It’s not just a matter of what we have called The Great Jackass Theory of Human Motivation, where you just throw more money at the workers. In fact, studies have shown that when you have a Knowledge Worker approach, workers place salary fourth in priority behind trust, respect and pride. Why? Because when people have intrinsic satisfaction in their work, extrinsic, or external, factors are less important. But when there are no intrinsic satisfactions in the work, then money becomes the most important thing. Why? With money you can buy satisfactions off the job. The whole-person 8th Habit unleashes internal motivation.

The execution gaps of clarity and commitment are also the primary source of time management problems. There is one simple reason—how people define the high-priority goals, along with mission and values, will govern every other decision. Therefore, when there is a lack of clarity and commitment, you will have nothing but confusion about what is truly important. The end result is that urgency will define importance. That which is popular, pressing, proximate and pleasant—in other words, that which is urgent—becomes important. The net result is that everyone is reading the tea leaves, putting their finger to the political winds, and kissing up to the hierarchy. Then the confusion gets pushed down through the entire organization in a compounded way. So until people develop clarity and commitment toward the mission, vision and values of the organization no amount of time management training will have any sustaining impact, except in people’s personal lives. As Charles Hummel once said:

The important task rarely must be done today, or even this week. . . . But the urgent task calls for instant action. . . . The momentary appeal of these tasks seems irresistible and important, and they devour our energy. But in the light of time’s perspective, their deceptive prominence fades; with a sense of loss we recall the vital task we pushed aside. We realize we’ve become slaves to the tyranny of the urgent.3

3. Translation: The Industrial Age approach is job descriptions. In the Knowledge Worker Age, you help align people’s jobs to their voices (talents and passions), and their jobs have a line of sight to accomplishing the team’s and organization’s high-priority goals.

4. Enabling: In many ways, enabling is the toughest execution gap to deal with, because it requires you to remove all the dysfunctional structural, systemic and other cultural barriers that we have been discussing throughout the book. These enabling or disabling structures and systems—recruiting, selecting, training and development, compensating, communicating, information, compensation, etc.—are exactly where many people get their sense of security and predictability in their work life. Unless there is genuine involvement in the strategic decision making, particularly regarding values and line-of-sight priorities, you won’t get sufficient emotional connection, trust and internal motivation to align deeply embedded structures and systems.

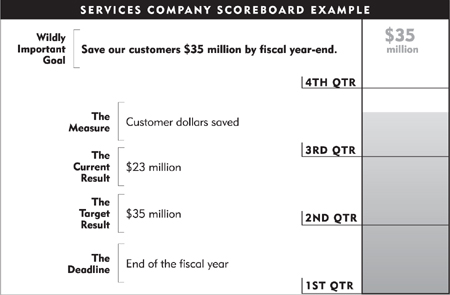

In the Industrial Age, people are an expense, and things, like equipment and technology, are an investment. Just think about this again! People . . . an expense; things . . . an investment! This is the bottom-line information system. It is sick bloodletting. With the 8th Habit approach to the Knowledge Worker Age, people can become involved in setting up a very powerful visual, compelling, real-time Scoreboard on both result and capability that reflects how well the systems and structures are aligned, to enable key goals to be accomplished.

5. Synergy: The Industrial Age is a compromise approach at best, and win-lose or lose-win at worst. Synergy in the Knowledge Worker Age enables Third Alternatives to be created. It’s an 8th Habit kind of communication, where people’s voices are identified and aligned with the organization’s voice so that the voices of different teams or departments harmonize together.

6. Accountability: The Industrial Age practices of “carrot-and-stick” motivation and “sandwich technique” performance appraisal are replaced by mutual accountability and open sharing of information against the top-priority goals that everyone understands. It’s almost like going into a soccer stadium or a football or baseball arena where the scoreboard displays information so that everyone in the entire arena knows exactly what’s happening.

Let’s tie all this together. Early in the book, I introduced the idea that everyone chooses one of two roads in life—one is the well-traveled road to mediocrity, the other the road to greatness. We’ve explored how the path to mediocrity straitjackets human potential and how the path to greatness unleashes and realizes human potential. The 8th Habit is the pathway to greatness, and greatness lies in Finding Your Voice and Inspiring Others to Find Theirs.

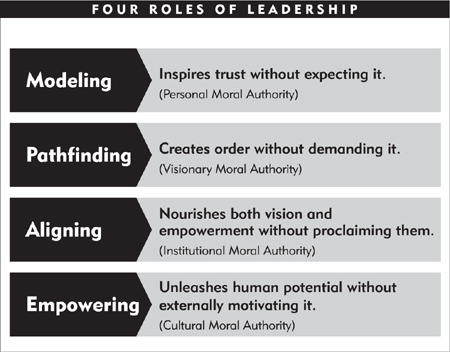

Together we’ve explored what could be called three kinds of greatness: personal greatness, leadership greatness and organizational greatness.*

Personal greatness is found as we discover our three birth-gifts—choice, principles and the four human intelligences. When we develop these gifts and intelligences, we cultivate a magnificent character full of vision, discipline and passion that is guided by conscience—one that is simultaneously courageous and kind. This kind of character is driven to make significant contributions that not only serve mankind but also reach and are focused on “the one.” Such character I would term primary greatness, whereas secondary greatness would include such things as talent, reputation, prestige, wealth and recognition.

Leadership greatness is achieved by people who, regardless of their position, choose to inspire others to find their voice. This is achieved through living the 4 Roles of Leadership.

Organizational greatness is achieved as the organization tackles the final challenge of translating their leadership roles and work (including mission, vision and values) into the principles or drivers of execution in an organization—clarity, commitment, translation, enabling, synergy and accountability. These drivers are also universal, timeless, self-evident principles—for organizations.

THE DIAGRAM THAT FOLLOWS summarizes the relationship between personal greatness, leadership greatness and organizational greatness. Organizations that govern and discipline themselves by all three truly hit what you might call the sweet spot. The sweet spot is the nexus where all three circles overlap. This is where the greatest expression of power and potential is found. When you hit the “sweet spot” of a racquet while playing tennis, or of the golf club when connecting with that little white ball, you know when you’ve hit it. It is exhilarating! It resonates. It just feels right. With no more effort than usual, that connection with the center releases a burst of power and the ball is sent soaring much farther and faster than usual. It is another way of referring to the power that is released when you “Find Your Voice” as an individual, team and organization.

There are four disciplines that, if practiced consistently, can close these execution gaps and vastly improve teams’ and organizations’ ability to focus on and execute their top priorities. We call them The 4 Disciplines of Execution. Of course, there are dozens of factors that influence execution. However, our research suggests that these four disciplines represent the 20 percent of activities that produce 80 percent of results, as they pertain to executing consistently with excellence on top priorities. You will notice that these four disciplines are consistent with, and flow out of, the three areas of greatness. They are the Sweet Spot (see 4DX at the center of the diagram), the power-releasing contact point, the set of next-step, actionable, “rubber meets the road,” laser-focused practices that will enable a team and organization to consistently get results.

Below is a summary of these four disciplines (4DX):

Discipline 1: Focus on the Wildly Important

There’s a key principle that many fail to understand about focusing an organization: People are naturally wired to focus on only one thing at a time (or at best very few) with excellence.

Suppose you have an 80 percent chance of achieving any particular goal with excellence. Add a second goal to that first goal, and research shows your chances of achieving both goals drop to 64 percent. Keep adding goals and the probability of achieving them plunges steeply. Juggle five goals at once, for example, and you only have a 33 percent chance of actually getting excellent results on all of them.

How vital it is, then, to focus diligently and intensely on only a few crucial goals.

Some objectives are clearly more critical than others. We must learn to distinguish between what is “merely important” and what is “wildly important.” A “wildly important goal” carries serious consequences. Failure to achieve these goals renders all other achievements relatively inconsequential.

Consider the situation of the air traffic controller. At any moment, hundreds of airplanes are in the air, and all of them are important—especially if you happen to be on one of them! But the controller cannot focus on them all at once. Her job is to land them one at a time, and to do so flawlessly. Every organization is in a similar position. Few can afford the luxury of “divided attention”; some goals simply must be landed right now.

So how do we know which goals are “wildly important” and will best help us execute our strategic plan? Sometimes it is immediately clear and obvious. At other times, analysis is needed. The Importance Screen is a valuable strategic planning tool that will help you prioritize your goals by running them through the economic, strategic, and stakeholder screens. In other words, it will help you assess which of all the potential goals would bring the most leverage in terms of economic, strategic, and stakeholder benefits. You may wish to use the Importance Screen when determining your top goals. This is pathfinding at the cutting edge of action.

The Stakeholder Screen. What are the most important things you should do to fulfill the needs of your stakeholders? Customers, employees, suppliers, investors and others all have a stake in these goals. Consider how the potential goals:

• increase customer loyalty.

• ignite the passion and energy of your people.

• favorably impact suppliers, vendors, business partners and investors.

The Strategic Screen. Consider how the potential goals affect the strategy of the organization, including whether or not the goal:

• directly supports the organization’s mission or purpose.

• leverages core competencies.

• increases market strength.

• increases competitive advantage.

Ask yourself: What is the most consequential thing we can do to advance our strategy?

The Economic Screen. A wildly important goal must contribute to the overall economics of the organization in some direct or indirect way. Ask yourself: Of all your potential goals, which few would bring you the most significant economic return? Consider the following:

• Cost reduction

• Improved cash flow

• Profitability

Even in a nonprofit organization, economics are still crucial, since every organization must have cash flow to survive.

PUTTING THE GOALS through the stakeholder strategic and economic screens positions a clear “why” behind the “what” of each goal.

In my estimation, a strategic plan will remain vague and lofty unless it is broken down into the two or three top priorities or “wildly important” goals (WIGs). Stakeholders at all levels of the organization should be involved in the identification of these crucial goals so that they have a greater level of commitment and understand the rationale behind each one.

To achieve results with excellence, you must focus on a few wildly important goals and set aside the merely important. Since human beings are wired to do only one thing at a time with excellence (or at best just a few), we must learn to narrow our focus. The reality is, far too many of us try to do far too many things. Like an air traffic controller, we need to learn to land one plane at a time—to do fewer things with excellence rather than many with mediocrity.

To practice this discipline you must clarify your team’s top two or three “wildly important” goals and carefully craft them to be in alignment with the organization’s top priorities.

To illustrate the underlying need for focus on “the vital few,” I invite you to watch a little film called It’s Not Just Important, It’s Wildly Important! This film is based upon actual interviews we conducted with our own clients, not with actors. It illustrates the misalignment and lack of goal clarity that pervades most organizations. It is humorous but all too indicative of the focus and execution problems most organizations face. Just go to www.The8thHabit.com/offers and select this title from the Films menu, and sit back and see if you don’t recognize a little of the organization for which you work.

A Scoreboard allows you to leverage a basic principle: People play differently when they’re keeping score.

Have you ever watched a street game of some kind—basketball, hockey, football—when the players were not keeping score? Players tend to do whatever they want, the game stops for a few jokes, and the playing is not very focused. But when they start keeping score, things change. There’s a new intensity. Huddles happen. Plays are improvised. Players adapt quickly to each new challenge. And the speed and tempo build dramatically.

The same thing happens at work. Without crystal-clear measures of success, people are never sure what the goal truly is. Without measures, the same goal is understood by a hundred different people in a hundred different ways. As a result, team members get off track doing things that might be urgent but less important. They work at an uncertain pace. Motivation flags.

That is why it’s so crucial to have a compelling, visible, accessible Scoreboard for your strategic plan and crucial goals. Most work groups have no clear measures of success, nor do they have any way to see how they are doing on their key priorities.

According to our xQ studies, only about one in three workers can refer to clear, accurate measures to gauge their progress or success on key goals. And only about three in 10 believe that rewards or consequences have anything to do with performance on measurable goals. Obviously, few workers have the feedback system they need to execute with precision.

Think of the tremendous motivating power of the Scoreboard. It is an inescapable picture of reality. Strategic success depends on it. Plans must adapt to it. Timing must adjust to it. Unless you can see the score, your strategies and plans are simply abstractions. So you must build a compelling Scoreboard and consistently update it. This is combining pathfinding and aligning at the cutting edge of action.

Through involvement and synergy (modeling the 7 Habits), identify the key measures for your organizational or team goals and make a visual representation of them. The Scoreboard should make three things absolutely clear: From what? To what? By when?

1. List your top priorities or “wildly important goals”—those your team simply must achieve.

2. Create a scoreboard for each one with these elements:

• The current result (where we are now)

• The target result (where we need to be)

• The deadline (by when)

The Scoreboard might take the form of a bar graph, a trend line, a pie chart or a Gantt chart. Or it might look like a thermometer or a speedometer or a scale. You decide—but make it visible, dynamic and accessible. Remember also that because ends preexist in the means, you might consider including measures in the Scoreboard regarding principle-centered values.

3. Post the Scoreboard and ask people to review it every day, every week, as appropriate. Meet over it, discuss it, and resolve issues as they come up.

All team members should be able to see the Scoreboard and watch it change moment by moment, day by day, or week by week. They should be discussing it all the time. They should never really take their minds off it. The compelling Scoreboard has the effect of keeping score in a street game. All of a sudden, the tempo changes. People work faster, conversations change, people adapt quickly to new issues. And you get to the goal more precisely and rapidly.

It’s one thing to come up with a new goal or strategy. It’s quite another to actually turn that goal into action, to break it down into new behaviors and activities at all levels, including the front line. There is a vast difference between the stated strategy and the real strategy. The stated strategy is what is communicated; the real strategy is what people do every day. To achieve goals you’ve never achieved before, you need to start doing things you’ve never done before. Just because the leaders may know what the goals are doesn’t mean that the people on the front line, where the real action takes place, know what to do. Goals will never be achieved until everyone on the team knows exactly what they’re supposed to do about them. In the last analysis, the front line produces the bottom line. They are the creative knowledge workers. Leadership, remember, is a choice, not a position; it can be distributed everywhere—at all levels of the organization. Also remember, you cannot hold people responsible for results if you supervise their methods. You then become responsible for results and rules replace human judgment, creativity and responsibility.

To practice this discipline, your team must get creative, must identify the new and better behaviors needed to achieve your goals, then translate them into weekly and daily tasks at all levels of the organization. This is empowering at the cutting edge of action.

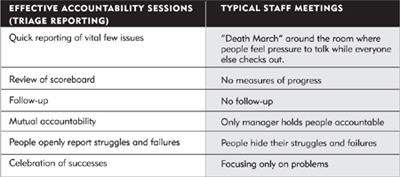

In the most effective teams, people meet frequently—monthly, weekly, or even daily—to account for their commitments, examine the Scoreboard, resolve issues, and decide how to support one another. Unless everyone on a team holds everyone else accountable—all of the time—the process will be dead on arrival. Mayor Rudolph Giuliani, widely credited with the renaissance of New York City, held regular “morning meetings” with his staff. The idea was to account for progress on key goals every single day. Reengaging less than weekly allows the team to drift off course and lose focus.

A self-empowering team, then, will focus and refocus in frequent accountability sessions. Such meetings are not like the typical staff meeting, where people talk about everything under the sun and can’t wait for the meeting to end so they can get back to their real work. The purpose of an effective accountability session is to move the key goals forward.

Three key practices are characteristic of effective accountability sessions:

• Triage Reporting

• Finding Third Alternatives

• Clearing the Path

Triage Reporting. In a hospital emergency room, you will often see a large notice posted that goes something like this: PATIENTS ARE TREATED IN ORDER OF SERIOUSNESS, NOT ARRIVAL. The medical staff conducts a process called “triage,” in which casualties are sorted and treated based on the severity of their condition. This is why your broken arm has to wait while the doctors work on a patient with a brain injury, even though you might have arrived first.

In triage reporting, everyone reports quickly on the vital few issues, leaving the less important issues for another time. They focus on key results, major problems, and high-level issues. This doesn’t mean that only “urgent” issues are discussed. It means that only “important” issues are discussed, even if some of these issues are not “urgent.” This table contrasts the typical staff meeting with an effective accountability session:

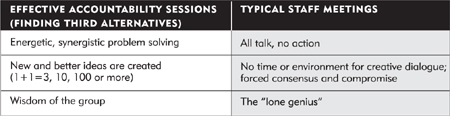

Finding Third Alternatives: In effective accountability sessions, there is intense focus on how to achieve the key goals. The principle here is that a new goal that we’ve never achieved before requires doing things we’ve never done before. That means we’re constantly looking for the new and better behavior that will get us to the goal. That’s why we must find “Third Alternatives”—courses of action that are better than my way or your way, but that are the product of our best thinking. Remember again, we produce synergy by honoring diversity or differences—that is, individual differences in the context of unity on mission, values, vision, and WIGs.

In such sessions you’ll see a lot of brainstorming going on, time allocated for creative dialogue. This table contrasts the typical staff meeting with an effective accountability session:

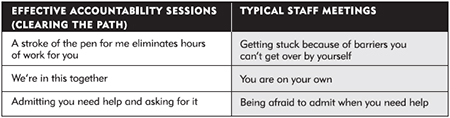

Clearing the Path: To a great extent, effective leadership consists of clearing the path of barriers and aligning goals and systems so that others can achieve their goals. In a true “win-win agreement” process, the manager agrees to clear the path, to do things only he or she can do, to enable the worker to achieve. Of course, it’s not just the manager who clears the path for others. It’s everyone’s job.

Thus, in an effective accountability session, you’ll hear people ask, “How can I clear the path for you?” or “I’m struggling with this issue and need some help.” or “What can we do for you to help you get that done?” This table contrasts the typical staff meeting with an effective accountability session:

This is aligning at the cutting edge of action.

As you can see, the 4 Disciplines represent a methodology for taking something that is usually considered a variable factor practiced by a few high performers—consistent execution—and turning it into something that is predictable, teachable and replicable. We’ve learned by research and experience that when these four disciplines are practiced by teams, units or organizations, they demonstrate a much greater ability to execute top priorities, again and again.** Execution then becomes institutionalized and is not a matter of luck or the influence of a few key leaders. Further, the key to institutionalizing a culture of execution is regularly measuring it.

Organizations need a new way to express and measure their collective ability to “focus and execute.” Again, we call it xQ—The “Execution Quotient.” Just as an IQ test uncovers gaps in intelligence, an xQ evaluation measures the “execution gap”—the gap between setting a goal and actually achieving it. The xQ score is a leading indicator of an organization’s ability to execute its most important goals. It’s no longer necessary to wait for the lagging indicators to tell you whether you’ve succeeded or not. By asking workers twenty-seven carefully crafted questions that take around fifteen minutes to answer, you can get at that leading indicator.†

Can you imagine the power of doing an xQ test from the grass roots up every three to six months, one that gives an accurate picture of the degree of focus and execution of the organization? It could be done formally and informally. In fact, the more mature the culture becomes, the narrower the difference will be between formal and informal information gathering. Then based on the xQ Questionnaire, strong grassroots cultural impetus would be given to aligning goals between departments and divisions so that the strategic critical priorities would be constantly focused on and executed. This would drive the Knowledge Worker Age model into the Age of Wisdom.*

HOPEFULLY YOU’RE BEGINNING to see how the 8th Habit—Find Your Voice and Inspire Others to Find Theirs—is another way of saying, “Use the empowering knowledge worker, whole-person model. Apply the 7 Habits (personal greatness), the 4 Roles of Leadership (leadership greatness) and the 6 principles or drivers to execution (organizational greatness) to that model.”

We move now to the pinnacle of the 8th Habit: Using Our Voices Wisely to Serve Others.

QUESTION & ANSWER

Q What is the difference between what you have traditionally taught as the 5 elements of a good win-win agreement and the 4 Disciplines of Execution?

A: At the basic principle level, there is no difference. The difference lies in semantics (how words are being used and defined), and in the overall context in which the 4 Disciplines are placed. Let me explain more fully. The 5 elements of a good win-win agreement are:

1. Desired Results

2. Guidelines

3. Resources

4. Accountability

5. Consequences

Desired results and guidelines are basically embodied in the first two disciplines of execution—establishing WIGs (Wildly Important Goals) and a compelling Scoreboard. As discussed earlier in the book, ends and means are inseparable; therefore, the accomplishment of desired results with the achievement of the WIGs can be interwoven when done in principle-centered ways.

The third element of a win-win agreement, resources, is implicitly involved in the third discipline of execution—translate lofty goals into specific actions. The fourth and fifth elements of a win-win performance agreement—accountability and consequences—are explicitly involved in the fourth discipline: You hold each other accountable, all of the time. Since consequences are the natural result of the accountability being given, they are also implicitly involved.

The great advantage of the 4 Disciplines approach to execution and team empowerment is that it comes out of a research-based study of execution gaps, the larger context of how the Industrial Age model produces those gaps, and how the Knowledge Worker Age model fills them.

* For more information on achieving sustained superior performance through developing all three forms of greatness, see Appendix 8.

** For more information on how to institutionalize The 4 Disciplines of Execution in your team or organization, see Appendix 5: Implementing the 4 Disciplines of Execution.

† For a more detailed summary of the results of the Harris Interactive study of 23,000 workers, managers and executives who took the xQ Questionnaire, see Appendix 6: xQ Results.

* If you are interested in taking the xQ Questionnaire without charge to personally assess your individual team’s, and organization’s ability to focus and execute on top priorities, go to www.The8thHabit.com/offers. You will receive directions on how to take the test. After completing the test, you will be given an xQ Report that summarizes your assessment and compares it to a composite average score of the many thousands of respondents. Further information will be given on how you can measure your entire team or organization.