Baratieri’s foreboding was well founded, and on 17 September 1895 Menelik called for general mobilization. Thousands of warriors converged on four regional assembly points, and of these about 35,000 gathered under Menelik himself. His empress Itegue Taitu also mobilized another 6,000. The rest were raised by governors and regional princes, the largest contingent being that of Menelik’s cousin Ras Mekonnen of Harar, who brought about 12,000 men. The exact size of the Ethiopian army is unknown; estimates range between 80,000 and 120,000, and at least 100,000 seems probable.

On 9 October 1895, Baratieri led a large Italian force 80 miles south from Adigrat to attack Ras Mangasha at Debre Aila. It was one of the rare instances when the Italians outnumbered the Ethiopians: Baratieri had 116 Italian officers, 672 Italian other ranks, 8,065 ascari, a few hundred militia and irregulars, and ten mountain guns, while Mangasha had only 4,000–5,000 warriors. The Italians lost 11 killed and 30 wounded, the Ethiopians 30 killed, 100 wounded, and 200 prisoners. Far from being cowed by the Italians’ superiority, one of the prisoners gave this ominous warning: ‘For the moment you have been victorious, because God so willed it; but wait a month or two, and you will see the soldiers of Menelik. They are as many in number as the locusts.’

Major-General Oreste Baratieri had fought as a Redshirt under Garibaldi in the war of Italian unification, and also participated in the brief and unsuccessful campaign against Austria in 1866. Nearly three decades later, his consolidation of control over Eritrea and his victories over the Mahdists and Ethiopians earned him an exaggerated reputation at home, but his career ended after the disaster at Adowa. It is said that he lost his pince-nez spectacles during the rout and, almost blind, had to have his horse led during the retreat. (Courtesy SME/US)

The Italians, too, were shipping in major reinforcements to deal with the situation. Between 25 December 1895 and 10 March 1896 they landed 1,537 officers, 38,063 men, 8,584 mules, and 100,000 barrels of supplies. Unfortunately for Baratieri, most of them landed only after he had marched into Tigré to confront Menelik, at the head of some 14,000 men (for his order of battle, see ‘The Italian Army’, below).

The Ethiopians’ own march towards the arena of battle was a long one even by their standards, requiring some groups to walk for 150 days over rough and often trackless terrain. On one route the men had to cross the loops of the same serpentine river 28 times. Much of the region had suffered from rinderpest (a deadly cattle disease) and drought, so Menelik set up food depots along the way to reduce the amount of foraging the army had to do. Typically of Ethiopian strategy, Menelik’s aim was to defeat the main Italian army, leaving smaller detachments to be mopped up later. When his vanguard came across Maj Pietro Toselli with 1,800 men and four mountain guns dug in at Amba Alagi, it simply bypassed them; Toselli’s force was too small to threaten the Ethiopians’ rear.

Amba Alagi and Mekele

Fatally for Toselli, however, two Ethiopian commanders found the temptation to strike the first blow irresistible. The Fitawrari Gebeyehu and the Gerazmach Tafese attacked the Italian position at Amba Alagi on 7 December 1895, and this assault attracted all the nearby warriors into the fray – some 30,000 men, including the commands of Ras Mekonnen and Ras Mangasha. Together they completely overwhelmed the Italians, who suffered 19 Italian officers (including Maj Toselli), 20 Italian other ranks, and 1,500 ascari killed, and three officers and 300 ascari wounded. The survivors fled some 35 miles north to the town and fort at Mekele, and the rest of the region was abandoned. The Ethiopians suffered an estimated 3,000 casualties; the two impulsive commanders were detained for disobeying orders, but once Menelik arrived on the scene he forgave them. (Had the battle not been such a total victory, their fate might have been much worse.)

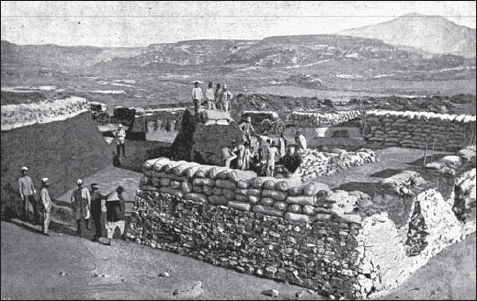

Bersaglieri, this time complete with their distinctive plumes, practise manning the walls of the fortified position at Addi Caieh in 1896. The Italians usually defended such positions successfully; although the Ethiopians had light artillery, they lacked the resources to maintain long sieges. Walls were often strengthened by adding a traditional African hedge of interwoven thorn-bushes, and by littering the ground in front of the defences with broken glass to slow down charges by bare-footed Ethiopians. (Courtesy SME/US)

Soon the advancing Ethiopian army reached Mekele; such an important fort could not be bypassed, and the vanguard surrounded it. The garrison consisted of 20 Italian officers, 13 Italian NCOs, 150 Italian privates, 1,000 ascari, and two mountain guns. A two-week siege ensued, during which the Ethiopian artillery proved to have a longer range than the Italian guns – 4,900 yards, as opposed to 4,200. The fort was systematically pounded, but frontal assaults proved costly and fruitless; outside the walls the Italians had laid barbed wire, and fields of sharpened stakes and broken bottles to discourage the bare-footed Ethiopians. The defenders shot off signal flares, and sent up an observation balloon to scare the ‘savages’; the Ethiopians were duly impressed, but reasoned that since these technological wonders did them no harm, they were of no importance. The siege continued.

Finally the attackers managed to cut off the fort’s water supply, and the Italian commander offered to surrender if the garrison could leave bearing their arms. Menelik agreed to these generous terms, both because he wanted to free up his army to march on, and because he could see a use for the prisoners. Ras Mekonnen was sent to ‘escort’ them back to Italian lines – a convenient way to bring a major part of the Ethiopian army deep into Italian-held territory without being molested.

The main Ethiopian force followed, avoiding the strong Italian fort at Adigrat and moving on to Adowa on 14 February 1896. They found the Italians dug into a strong position at Sauria, 16 miles to the east, with their flanks guarded by almost impassable terrain. Menelik decided not to attack, hoping instead to lure the Italians onto more favourable ground where the superior Ethiopian numbers could be used to full effect.

The waiting game

There now followed a two-week pause in activity by both sides. Withdrawal would have meant a severe loss of face for either commander, and would probably have ended the campaign without a decision. An Ethiopian army, consisting of levies commanded by regional leaders with their own agendas, had to be used before it simply broke up and drifted apart. The Italian army had a series of recent defeats on its record, and Baratieri was receiving strident cables from Rome insisting on a decisive victory (Prime Minister Crispi had wanted to replace Baratieri, but the general was saved by the support of King Umberto). The Italian commander had exuded confidence before the campaign, thinking that Menelik could gather at most 60,000 men – a force that the Italians could probably have dealt with, given their strong position. But when twice that number showed up, Baratieri’s position became hazardous, and his previous boasts came back to goad him.

On 29 February (1896 being a leap year), Menelik could wait no longer. His supplies were nearly exhausted, and he decided that a small victory would be better than none. He announced that the next day he would lead his army around the Italians and north into the province of Hamacen, which included Asmara, now the seat of the colonial government in Eritrea. He apparently intended to ravage the countryside, and perhaps to strike at Asmara before withdrawing.

In one of the ironies of military history, that very night Gen Baratieri – who favoured a temporary withdrawal – was persuaded both by the unanimous advice of his brigade commanders, and by constant pressure from Rome, to order an advance. His army, too, had only a few days’ supplies left, and spies informed him that much of the Ethiopian army had scattered across the countryside foraging, or were praying in various churches around Adowa in preparation for a feast day on 1 March. These reports were exaggerated, either by mistake or design. While some warriors were indeed foraging or praying, most had not strayed far; and in any case, the Ethiopian numbers were such that, even with part of the force absent, they still outnumbered the Italians by a factor of anything between 4:1 and 8:1.

Photo of part of the defences of the Italian fort at Adigrat. Built in March 1895 as a base for operations in Tigré, this had to be abandoned under the peace terms agreed a year later after the battle of Adowa. (Piero Crociani Collection)