Full freedom from almost anorexia is possible. Don’t let anyone convince you otherwise—especially Ed, who may find this chapter too hopeful. Both research and clinical experience support the reality that people who struggle with food and body image problems can ultimately reach a place we call fully recovered. This means a lot more than just learning how to eat normally and restoring your weight. Recovery also means getting your life back. It took time, but Samantha, who battled almost anorexia on her way out of anorexia nervosa, did just that.

Dr. Thomas first met Samantha during her post-doctoral fellowship, when she got paged to do a consult in the hospital’s psychiatric inpatient unit. Noting the “trainee” designation on Dr. Thomas’s badge, Samantha immediately sat up in bed and remarked, “I’ll be a great training case for you. I probably have the worst case of anorexia you’ll ever see.”

As Samantha told her story, waving her stick-thin arms for emphasis, Dr. Thomas realized that Samantha might not be kidding. At twenty-one years old, she had struggled with anorexia for ten years, racking up admissions at every single inpatient and residential treatment center in New England. “They keep kicking me out because they don’t know what to do with me,” she boasted. “I’ve even ripped out my feeding tube and jumped out of first-floor windows to avoid eating meals. Most doctors are scared to work with me.” With Samantha’s frighteningly frail body and a history of a dangerously low heart rate and hypokalemia (lower than normal level of potassium in the bloodstream), Dr. Thomas could see why. Before being admitted, Samantha was bingeing and purging up to seven times per day. On nonbinge days, she fasted completely.

But as Samantha continued talking, Dr. Thomas thought she detected a hairline crack in Samantha’s brave facade. The truth was that Samantha had given up a lot to maintain her anorexia. Her parents had stopped contacting her after they’d lost their petition for medical guardianship, and she was currently in a relationship with a man who physically abused her. After riding a merry-go-round of eating disorder remissions and relapses, Samantha felt exhausted and hopeless. “I don’t know what they’re teaching you here,” she said, rolling her eyes. “But you should know that eating disorders are something you never really get over.” Dr. Thomas cocked her head for a minute and replied conspiratorially, “A lot of people think that, but since I’m still in training, I’m not so sure. How would you like to prove them wrong?”

It took four years of therapy and several more inpatient stays, but Samantha finally beat anorexia. She worked incredibly hard to get her weight up to the bottom of the normal range for her body. Although she still restricted some and binged and purged intermittently, her disordered-eating behaviors were far less frequent and intense than before. She ultimately broke up with her abusive boyfriend and started dating a man named Eric, whose steadfast calmness was the perfect foil for her dramatic flair. After they got married in a small ceremony with family and close friends, Samantha was thrilled to learn she was pregnant. She resolved to stop bingeing and purging completely and to markedly increase her calorie intake to support the baby’s growth. She couldn’t have been happier when she gave birth to Madison, a healthy baby girl. Samantha was so pleased with how far she had progressed that she didn’t believe she needed to go any further. So when Dr. Thomas suggested that she bring a chocolate bar to eat at their first postnatal therapy session, Samantha snapped. “What do you want from me?” she demanded. “I’ve gained weight. I’ve stopped bingeing and purging. I even had a baby! Why do I have to prove that I can eat some stupid chocolate bar now—when I’ve already done everything you’ve asked?”

Dr. Thomas validated Samantha’s extremely hard work but then expressed her concern that, although Samantha had overcome anorexia nervosa, she continued to struggle with almost anorexia, or residual symptoms of her eating disorder. For example, Samantha ate the same three “safe” meals every day and brought her own food in plastic containers when she visited family for the holidays. Sleep deprived from waking up multiple times per night to nurse her infant, she still prepared three dinners every night—a salad for herself, organic baby food for Madison, and meat and potatoes for her husband. While her baby napped, she felt compelled to do postnatal yoga DVDs or hit the elliptical machine. She obsessed about losing the “baby weight.” Although she did lose this weight, she never lost enough to be diagnosed with anorexia again. However, she suffered from atypical anorexia at this point in her life, a time when she didn’t even allow her friends to throw her a baby shower: she didn’t want them to take photos of her “looking fat.”

“You have come further than you ever thought you could, but I know you can have an even healthier relationship with food,” Dr. Thomas persisted. “Do you really want to settle for almost recovered?”

During the recovery process from either almost anorexia or a full-blown eating disorder, you may notice that you reach certain plateaus. Maybe you finally stop bingeing, which is a triumph, but you are restricting more than ever—a problem that many people don’t like to admit. Or possibly you finally are eating enough, but now you experience intense feelings of fatness. During these times, it is crucial to pat yourself on the back and acknowledge how far you have come. But it is equally important to recognize that you still have some room to grow. In a longitudinal study conducted by clinical psychologist Kamryn Eddy and colleagues, many women with an intake diagnosis of anorexia or bulimia nervosa recovered during the nine-year follow-up period. However, the transition was rarely black-and-white; more than three quarters exhibited subclinical eating disorders at some point during the study.1

The question ultimately becomes “How free do you want to be?” You don’t have to settle for lingering eating-disordered thoughts and attitudes. With time, patience, and continued growth, you can ultimately reach a place where you don’t even hear Ed anymore. Jenni often compares her personal Ed to a muscle: When she engaged Ed and obeyed him, he grew bigger and stronger. But when she stopped listening and began to trust herself, Ed atrophied like a muscle that wasn’t getting used. Essentially, her eating disorder wasted away slowly, just like her calf muscle had when she broke her foot.

When Jenni’s eating disorder “muscle” was atrophying, it wasn’t uncommon for a conversation with Ed to sound something like this:

| Ed: | You need to lose a few pounds. |

| Jenni: | |

| Ed: | Let’s go to the store and binge like old times. |

| Jenni: | |

| Ed: | Earth to Jenni—are you still there? |

Yes, you got it: these were not really conversations at all. Eventually, Jenni reached a point where she simply ignored Ed. The more she was able to do this, the less he spoke. In time, he stopped talking altogether.

When your disordered-eating behaviors and thoughts first fade into the background, you might find yourself maintaining a healthy weight and even a positive body image—and yet, feel completely miserable. Once again, this is just a phase. It indicates that you have made tremendous progress. It means keep going. The beginning of a life without Ed can feel unfamiliar. Feelings of depression can even arise when you stop turning to (or away from) food. (If the depressive symptoms persist, and especially if they get worse, we recommend consulting a health care professional for assessment and treatment. Even a mild depression can undermine your success in becoming fully recovered from almost anorexia or other eating disorders.) But you will ultimately find joy and peace if you face your fears both at the table and on the scale. A full recovery, of course, does not mean that you will be free from all problems in your life. (If we figure out how to do that, we will definitely write another book!) While people can recover from almost anorexia and other officially recognized eating disorders, no one is ever completely recovered from life, which will always be a journey with diverse challenges. But when you are recovered, you will have the strength—more than ever before—to face obstacles head-on while simultaneously knowing when it’s okay to let go. Because life is a continual growth process, some people, especially those who participate in Twelve Step programs, refer to themselves as being “in recovery.” But try not to get caught up in semantics. The important thing to know is that independence from disordered eating is possible, regardless of what you personally choose to call it.

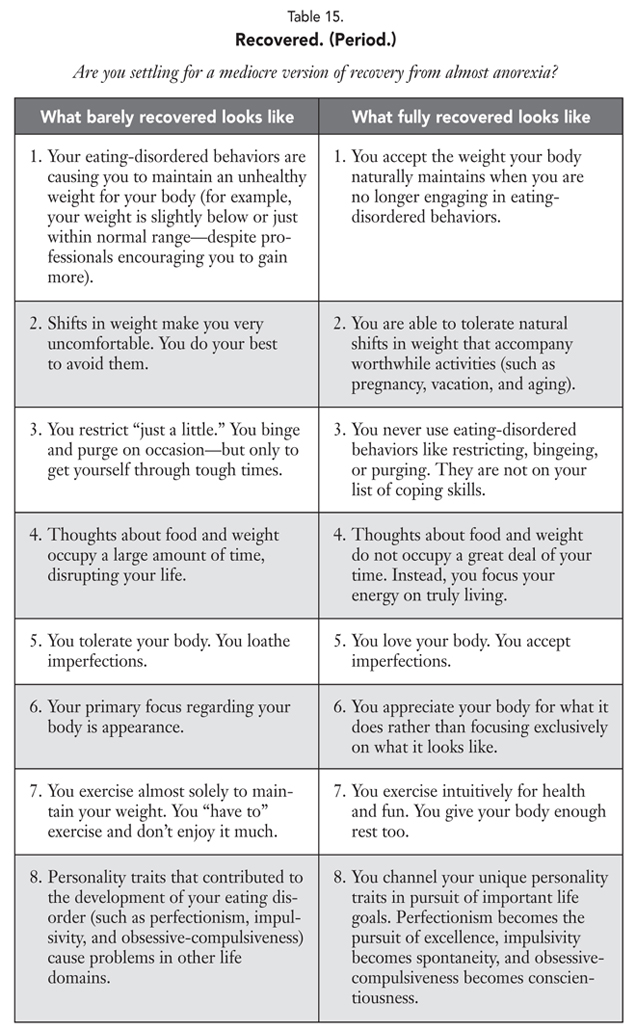

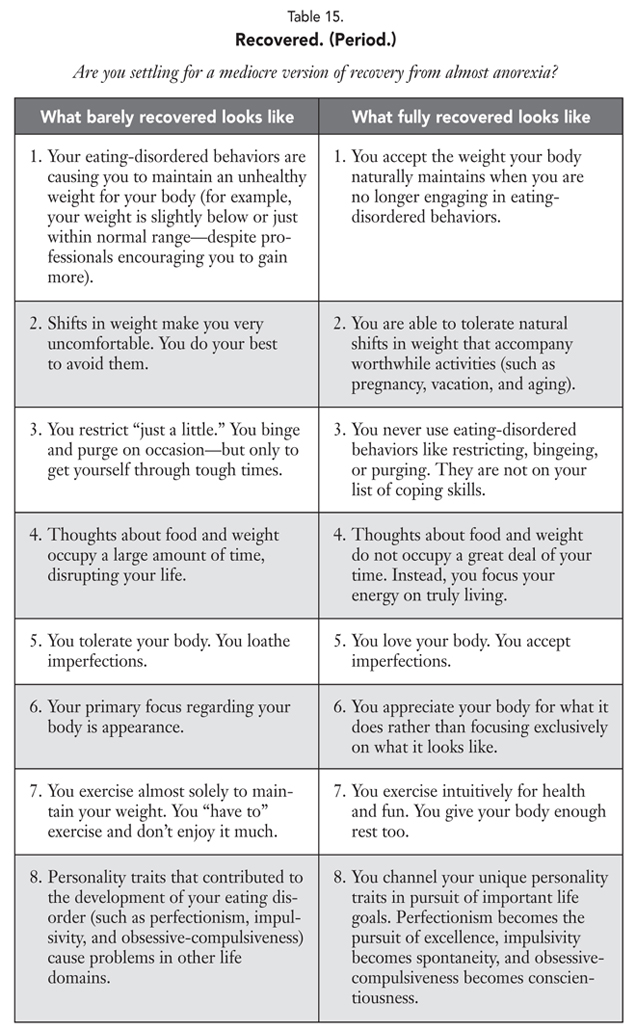

What does freedom mean to you? In her book 100 Questions & Answers about Eating Disorders, marriage and family therapist Carolyn Costin, who herself recovered from anorexia nervosa, defines recovery this way: “Being recovered is when a person can accept his or her natural body size and shape and no longer has a self-destructive relationship with food or exercise. When you are recovered, food and weight take a proper perspective in your life, and what you weigh is not more important than who you are; in fact, actual numbers are of little or no importance at all. When recovered, you will not compromise your health or betray your soul to look a certain way, wear a certain size, or reach a certain number on a scale. When you are recovered, you do not use eating disorder behaviors to deal with, distract from, or cope with other problems.”2 Are you settling for barely recovered? To help you find out, see the table 15 checklist. Similar to the normal eating table in chapter 7, you might find yourself in both columns at any given point on the same day. The goal is to move, in all areas listed, more toward “fully recovered” on the right. And, ultimately, if you keep moving, you will find yourself living fully recovered.

This exercise can be downloaded at www.almostanorexic.com.

You may believe that once you struggle with disordered eating, you always will. A study of individuals previously treated for anorexia nervosa found that 25 percent did not believe that full recovery was possible.3 At the height of her illness, Jenni was among them. But she ultimately broke free—after hearing Ed’s voice for more than twenty years. Similarly, Dr. Thomas recently worked with a remarkable woman who made major improvements at the age of sixty-five—after fifty years of anorexia!

But if you don’t believe us, believe the research. In three recent studies of individuals with EDNOS who received outpatient therapy for eating disorders (some after having been ill for many years), two-thirds were abstinent from disordered-eating behaviors one year after completing treatment.4 And although treatment typically speeds the recovery process, two recent prospective studies demonstrated that more than three-quarters of those with EDNOS recovered over the course of four to five years, regardless of whether they were treated during the course of the study.5 And we continue to be hopeful about the rest.

There are many scientific reasons to predict that recovery rates for almost anorexia and other eating disorders will continue to improve with time. First, many recovery statistics are based on individuals who were ill long before effective treatments were developed. Indeed, therapist manuals for the two best-studied outpatient eating disorder treatments—family-based treatment for anorexia and cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia and EDNOS—were just published in the last few years.6 This means that true recovery rates today may be even higher than earlier studies reflect. Second, novel treatments are constantly being developed, and clinical researchers are increasingly raising the bar for testing them. Whereas previous studies required just weight gain and menstrual recovery to declare anorexia treatment successful,7 recent studies (including some of those described earlier) have used more rigorous definitions of recovery that also require abstinence from eating-disordered behaviors and normalization of attitudes toward food and weight.8

Before Dr. Thomas became Dr. Thomas, she was an aspiring ballerina at the Anaheim Ballet. Her teachers had a tradition that whenever a student—whether beginning or advanced—fell down, the whole class would clap and shout “Progress!” They believed that dancers who executed every step perfectly couldn’t be truly challenging themselves and that real improvement could only come from falling down, getting back up, and trying again. Given how many of their students went on to dance professionally (Dr. Thomas’s childhood rival, Amy Watson, is now a principal dancer with the Royal Danish Ballet), they were probably right.

In our experience, recovery from disordered eating is like this. The beginning is filled with awkward moments, fear of falling—and some actual falling. You might have heard “falls” referred to as setbacks, slipups, relapses, or simply lapses in behavior. We don’t care what words you use. What is crucial is that, like Jenni’s favorite Japanese proverb says, if you “fall down seven times,” you “stand up eight.” And the sooner you stand up, the better. It is easier to get back on track after one night of restricting (a lapse) than six weeks of bingeing and purging (a relapse).

At first, just standing back up is a triumph, but the next step is figuring out what knocked you down in the first place. Research has identified many predictors of eating disorder relapse. Some may seem obvious, like the persistence of body image disturbance, insufficient caloric intake, and excessive exercise after acute symptom remission.9 Others are not directly related to food and weight—like work stress (such as being laid off), social stressors (such as breaking up with a close friend), and low overall psychosocial functioning—but nonetheless trigger disordered-eating behaviors. 10 The best way to identify your own individual triggers is to ask yourself immediately after a lapse, “Why did I feel compelled to return to a disordered-eating behavior just then?” When you’ve identified your triggers, start brainstorming ways to handle each of them in a healthy way.

Times of transition can be triggering to many people. For example, many students are fearful of gaining the dreaded “freshman fifteen” pounds during their first year on campus—even though such a gain is a myth.11 Developing or returning to eating disorder symptoms is common in college. In one study, 49 percent of female students reported at least one symptom of disordered eating (such as strict dieting, bingeing, or purging) in the past year.12 In a study of male undergraduates, 25 percent reported binge eating and 24 percent reported fasting in the past month.13 Obviously, going to college is not the only transition that can be difficult. Others that can pose problems include getting divorced or even joyful times like getting married or having a baby. Keep in mind that just because certain times in life can be problematic does not mean that they have to be. Clinical psychologist Margo Maine told us, “I warn all my patients and their families about what I call ‘the trouble with transitions.’ Just as eating disorders initially develop at ages 13 to 15 and 17 to 19—during school transitions, physical changes in the body, and huge steps away from the family and into the world—we meet lots of transitions in adulthood and have little time or support to process these.”14 Surround yourself with social support to protect yourself during these times. And don’t forget that you can be your own support, too, by practicing good self-care.

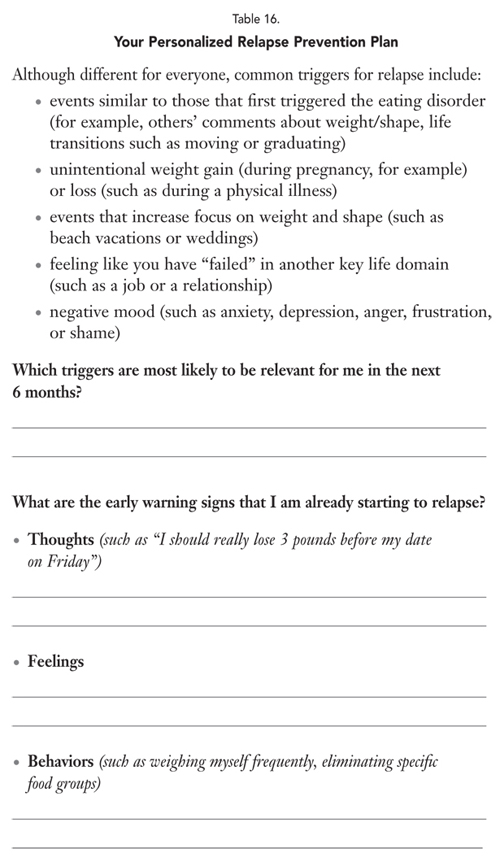

Watching out for yourself includes recognizing that slipping into destructive eating behaviors begins far before the actual bingeing, purging, or restricting. If you binge, for instance, the beginning of that setback might have actually happened days earlier when you let a friend take advantage of you. Stuffing your resentment—not reaching for the food—might be considered the start of that binge. For this reason, one of the most effective relapse prevention strategies is to avoid getting to the place where you are on the verge of symptom use. To do this, you will need a recovery toolbox filled with tools that really work. If certain ideas and exercises in this book have been particularly helpful to you, consider listing them in your personalized relapse prevention plan in table 16 or in a notebook.

________________________________________________________________________________________

What can I do to get back on track so a lapse doesn’t become a full-blown relapse?

Strategies that have worked for me in the past include:

________________________________________________________________________________________

Jenni’s former dietitian, Reba Sloan, has explained, “Treating an eating disorder is like fighting a forest fire. We must put the entire fire out. If an ‘ember’ is still smoldering, there is a chance that the fire will be reignited.”15 If you keep falling into disordered-eating behaviors, maybe an ember of Ed is still burning in your life. Are you trying to keep your weight below a specific number? Is Ed still a coping mechanism? We all have a list of ways that we cope with life. To fully recover, Ed’s name has to be taken off of that list completely. In the beginning, moving Ed’s name to the bottom of the list is a great feat. But in the end, his name can’t be scribbled in anywhere. Full freedom means that Ed is not an option. Period.

Sometimes, people have made promises to themselves about the circumstances under which they will truly commit to recovery. I’ll stop using eating-disordered behaviors when I graduate college. When I get married. This is a trap. Samantha thought that she would give up her anorexia when she had a baby. But as long as she was too underweight to get her period, getting pregnant wasn’t even a possibility.

If you keep lapsing into disordered-eating behaviors, you might be trying to hold on to the “good” parts of almost anorexia while getting rid of the bad. But to get better, you cannot hold on to any part, which means saying good-bye to it all—even to the good. Remember from your “Friend” letter in chapter 6 that disordered eating serves a purpose in your life. Try rewriting that letter, which expressed gratitude to Ed, to also say good-bye. Letting go will be a grieving process, so feelings of sadness and even anger are common. But if you remain patient and stay the course with recovery, these feelings will usually pass.

When you first let go of almost anorexia, it might be helpful to remind yourself that you can always go back. Dr. Thomas often says to patients, “You have an impressive ability to restrict food, and no one can ever take that away from you. It’s not like you’re going to ‘forget’ how to be anorexic.” Similarly, you can always go back to bingeing and purging if you make that choice. But our bet is that, once you experience the freedom of full recovery, you won’t want to.

You recover from an eating disorder in order to recover your life. This means that recovery will bring you face to face with your dreams. This is both exciting and scary. When you first start to feel better, you might wonder, like many people, Who am I without my eating disorder? This part of recovery is kind of like being placed in an empty room. The room is dull, not to mention uncomfortable, with no place to sit. But recovery is really about decorating the room. This is the fun part. You can fill up your room with anything at all—your favorite color, passions, relationships, and more.

Discussing the more recent twenty-five-year follow-up interviews of women with anorexia and bulimia nervosa in the longitudinal study that we described earlier, Dr. Kamryn Eddy told us that one of the best indicators of recovery was redefining one’s identity. She said, “Eating disorder recovery involves an attentional shift away from a self-worth based solely on weight, shape, eating, and their control and toward a sense of self that is founded in a broader collection of values and experiences. While the mechanisms of this progression from illness to wellness are difficult to describe, some women cite engagement in relationships—falling in love or having children, feeling connected with animals, and being valued at work—as experiences that impel this shift by giving their lives meaning.”16

Jenni welcomes readers to post comments, questions, and words of inspiration on her Facebook and other social media pages. One particular post that caught her eye was from college student Amanda Olsen who said, “Finally found a dream big enough to beat Ed!” Battling Ed since middle school, Amanda had been through many ups and downs. In high school, her disordered eating even caused her to miss out on an opportunity to be a student ambassador in Japan—and she loved Japanese culture more than almost anything else. Years later when an opportunity arose yet again for Amanda to study abroad, Ed immediately said, “You can’t do it.” But then she asked herself, Why not? Amanda told us, “I realized then that all of my reasons for not being able to go were related to Ed, so for the first time, I genuinely wanted to get better for me. Since then, I’ve been working harder than ever before to achieve my dream.”17 Ultimately, Amanda was accepted to a university in Japan.

Do you have a dream big enough to beat Ed? You might have a dream for something you desire within the next five minutes (to finish this chapter), five hours (to eat your next meal), five days (to buy clothes that fit your body now, not five pounds from now!), five months (to go hiking in Costa Rica with your friends), or five years (to be in a happy relationship with a partner other than Ed).

You might even consider making a list of all the dreams that Ed says are not possible for you. Then start doing those things and checking them off your list. One of Dr. Thomas’s patients referred to this as her “recovery bucket list.” Without Ed constantly telling her that she was fat, she could finally take a dance class, go on a date, and tell her recovery story at a local high school. Share your dream with us at www.jennischaefer.com.

People often ask us how they can share their recovery story in an effort to help others. There are all kinds of ways to share your story, but first ask yourself if you are ready. If talking with others about almost anorexia only triggers you to fall backward, then obviously it’s not worth it. From experience, Jenni recommends that people wait to share their story until they have at least one year of solid recovery and also have experienced some success at avoiding relapse during difficult times. For some, their passion ultimately leads them to working professionally in the eating disorders field. If this is you, determine whether your desire is tied to an unhealthy need to stay connected with disordered eating (If I can’t have an Ed, I can at least talk with other people’s Eds all day) or if you genuinely want to help others. Guard against letting your “recovered” status define who you are as a person, even if it does end up being what you do as your job. Explaining his decision to specialize in eating disorders, physician Mark Warren, who is recovered himself, told us, “Given my visceral knowledge of the disorder, my optimism about recovery, my desire to have a more organized treatment world for those with whom I shared an experience, there was little else that held my attention like working in the eating disorder field.” To help those considering following a similar path, he said, “This is not the right work if you feel triggered and unsafe. This is the right work for you if it gives you energy and makes you feel more whole.”18

Don’t sell yourself short by getting halfway or even three quarters of the way better. Push past the various versions of “pseudorecovery”19 to a complete one. It might be tempting, but try not to settle for even 99 percent better. Sure, we have heard people argue that they can survive in an almost-recovered phase, so why move further? And that might be true. But surviving and truly living are two different things.

You might be wondering how you will know when you are fully recovered. Hindsight often tells people when they are better, so try not to worry about exactly where you are along the way. Jenni, for instance, did not realize that she was fully recovered until friends and family started pointing it out. If your loved one is struggling, you can be a mirror like this—reflecting what you see, especially in terms of progress. When Jenni looked back at her life, she realized that she had been through many stressful periods without turning to eating-disordered behaviors (or even thinking about it). She discovered that she had formed genuine friendships and was living a joyful life. That’s recovered. We have connected with countless men and women who have found this place of contentment and health. You can get there too.

Trade in jumping on the scale for jumping into life. This might surprise you, but a standard bathroom scale works, in large part, from one little spring, which snaps the dial back to zero when you step off. We have known people in recovery who have destroyed their scales, removed the spring, and then used it as a reminder to spring—not into body loathing, but into life. And that is exactly what recovering from disordered eating will help you to do. When Jenni first tried to get Life Without Ed published, literary agents and publishers were not interested. Okay, that’s an understatement: she has a pile of more than fifty rejection letters at her house! Jenni did not quit despite this rejection, because she had already recovered from Ed, which was 100 times harder than facing this rejection. After you overcome almost anorexia—possibly one of the most difficult challenges you will ever face—something like a pile of rejection letters won’t seem like a big deal. Your fresh perspective on life will move you in a different direction—one you never imagined possible. And with the tools from this book, you have the power to write a brand-new ending to your story.