When Lewis arrived in Washington, he and Jefferson went to work immediately on the instructions. Jefferson had circulated them among his Cabinet and had their replies to consider.

Secretary of State James Madison had wondered “if the laws give any authority at present beyond the limits of the U.S?”1 That was a shorthand way of raising the point that this expedition was going into territory belonging to France and administered by Spain, whose governments might regard it as a military reconnaissance, or even an invasion.

Attorney General Levi Lincoln warned Jefferson that, “because of the perverse, hostile, and malignant state of the opposition, with their facility, of imposing on the public mind, & producing excitements, every measure originating with the executive will be attacked, with a virulence,” including the expedition. For his part, Lincoln declared, “I consider the enterprise of national consequence.”

But as a politician Lincoln knew that more justification was needed, to keep the Federalists from howling at the cost. He came up with a rationale that would appeal to the New England clergy: advertise the thing as a mission to elevate the religious beliefs of the heathen Indians. “If the enterprise appears to be, an attempt to advance them, it will by many people, on that account, be justified, however calamitous the issue.” Jefferson bought the idea; in his final instructions he ordered Lewis to learn what he could about Indian religion, because it would help “those who may endeavor to civilize & instruct them.”

Lincoln had another important suggestion. Jefferson had written that if Lewis were faced with certain destruction he should retreat rather than offer opposition. Lincoln commented, “From my ideas of Capt. Lewis he will be much more likely, in case of difficulty, to push to far, than to recede too soon. Would it not be well to change the term, ‘certain destruction’ into probable destruction & to add—that these dangers are never to be encountered, which vigilance percaution & attention can secure against, at a reasonable expense.”2

There is more than a hint here that Lincoln was one of the president’s advisers who feared Lewis was a reckless risk-taker, one of those Virginia gentlemen who would overreact to any challenge to his honor or bravery. Jefferson may have agreed; in any event, he adopted the wording Lincoln suggested.

Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin saw nothing in Jefferson’s draft that needed changing, but he did want some things added. He wanted to know more about the Spanish posts in Louisiana and the British activities along the Missouri River. “The future destinies of the Missouri country are of vast importance to the U.S.,” Gallatin wrote, “it being perhaps the only large tract of country and certainly the first which lying out of the boundaries of the Union will be settled by the people of the U. States.” Therefore, he wanted as much information as possible on the Missouri drainage.

As the instructions indicated, Jefferson had a multitude of motives for sending off the expedition, but number one for him was the all-water route to the Pacific. Not for Gallatin. He flatly stated, “The great object is to ascertain whether from its extent & fertility the Missouri country is susceptible of a large population, in the same manner as the corresponding tract on the Ohio.” He wanted Lewis enjoined to describe the soil and make judgments on its fertility by noticing the prevailing species of timber, to assess annual rainfall, temperature extremes, and other factors important to farmers.3

Jefferson adopted most of Gallatin’s suggestions, but in its final form the instructions issued by Commander-in-Chief Jefferson to Captain Meriwether Lewis put exploration and commerce ahead of agriculture. “The object of your mission,” Jefferson wrote, “is to explore the Missouri river, & such principal stream of it, as, by it’s course and communication with the waters of the Pacific ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregan, Colorado or any other river may offer the most direct & practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.”

Commerce being the principal object, Jefferson naturally wanted Lewis to learn what he could about the routes used by the British traders coming down from Canada to trade with the Missouri River tribes, and about their trading methods and practice. He wanted Lewis to make suggestions as to how the fur trade, currently dominated by the British, could be taken over by Americans using the Missouri route.

Good maps were essential to commerce. So Jefferson’s orders read, “Beginning at the mouth of the Missouri, you will take careful observations of latitude & longitude, at all remarkable points on the river, & especially at the mouths of rivers, at rapids, at islands, & other places & objects distinguished by such natural marks & characters of a durable kind.” Jefferson admonished Lewis to write his figures and observations “distinctly & intelligibly” and to make multiple copies, one of these to be “on the paper of the birch, as less liable to injury from damp than common paper.”

The fur trade would require knowledge of the Indian tribes. Jefferson instructed Lewis to learn the names of the nations, and their numbers, the extent of their possessions, their relations with other tribes, their languages, traditions, monuments, their occupations—whether agriculture or fishing or hunting or war—and the implements they used for those activities, their food, clothing, and housing, the diseases prevalent among them and the remedies they used, their laws and customs, and—last on the list but first in importance—“articles of commerce they may need or furnish, & to what extent.” This was an ethnographer’s dream-come-true set of marching orders.

“In all your intercourse with the natives,” Jefferson went on, “treat them in the most friendly & conciliatory manner which their own conduct will admit.” Lewis should “satisfy them of your journey’s innocence,” but simultaneously tell them of the size and strength of the United States. He should temper that implied threat by assuring the tribes of our wish to be “neighborly” and of our peaceful intentions: Americans only wished to trade with them. Lewis should invite a few chiefs to come to Washington for a visit, and arrange for some Indian children to come to the United States and be “brought up with us, & taught such arts as may be useful to them.”

On the distinct possibility of an Indian attack, Jefferson was specific. If faced by a superior force determined to stop the expedition, “you must decline it’s further pursuit, and return. In the loss of yourselves, we should lose also the information you will have acquired. . . . To you own discretion therefore must be left the degree of danger you may risk, and the point at which you should decline, only saying we wish you to err on the side of your safety, and to bring back your party safe even if it be with less information.”

Jefferson told Lewis that, “on the accident of your death, you are hereby authorised to name the person who shall succeed to the command.”

When Lewis reached the Pacific Coast, he should seek out a European trading vessel and possibly sail back to the United States on it. Or he could send back a copy of the journals with two men, if he wished, and return by the route he had come.

Taken all together, the military section of Jefferson’s orders was all that a company commander setting off on an expedition could hope for. He had the authority he needed, including the specific permission from the commander-in-chief to make his judgments in the field.

Jefferson realized that, when Lewis reached the Pacific, “You will be without money, clothes or provisions.” To deal with that situation, Jefferson provided a letter of credit for Lewis, authorizing him to draw on any agency of the U.S. government anywhere in the world, anything he wanted. “I also ask of the Consuls, agents, merchants & citizens of any nation to furnish you with those supplies which your necessities may call for. . . . And to give more entire satisfaction & confidence to those who may be disposed to aid you, I Thomas Jefferson, President of the United States of America, have written this letter of general credit for you with my own hand, and signed it with my name.”

In its final version, dated July 4, 1803, this must be the most unlimited letter of credit ever issued by an American president.

Beyond commerce, the purpose of the expedition was to discover flora and fauna. The instructions ordered Lewis to notice and comment on the soil, the plant and animal life—especially plants not known in the United States—dinosaur bones, and volcanoes. Jefferson wanted to know about “mineral productions of every kind,” but the ones he listed were limestone, pit coal, and salt.

There is no direct order to keep a daily journal. Jefferson did write about the possibility of sending Indians down the Missouri to St. Louis, carrying letters and “a copy of your journal, notes & observations,” the only use of the word “journal” in the instructions, and he did tell Lewis to send “a copy of your notes” by sea if he could, but there is no order about journal keeping.4 Perhaps it was a taken-for-granted matter; perhaps, in their many long discussions about the instructions, Jefferson made the order orally.

Donald Jackson’s description of Jefferson’s instructions cannot be bettered: “They embrace years of study and wonder, the collected wisdom of his government colleagues and his Philadelphia friends; they barely conceal his excitement at realizing that at last he would have facts, not vague guesses, about the Stony Mountains, the river courses, the wild Indian tribes, the flora and fauna of untrodden places.”5

•

As they talked about the instructions, Lewis and Jefferson also discussed such matters as when Lewis could get going, what additional instruments and maps he would need, the size of the party and additional supplies, what the War Department could contribute to the expedition, and the negotiations over Louisiana. All these subjects were intermingled. They came together in the need for another officer.

Recognition of that need evidently came simultaneously; it certainly came naturally. The arguments for such an appointment were overwhelming. The instructions called for information in so many areas that one man could hardly provide it all and certainly could not do it all well. It was plain common sense to have two officers, so that if something happened to one the other could bring back the maps, scientific discoveries, descriptions of the Indians encountered, and all the rest. A second officer would be a help in enforcing discipline, and in fighting Indians if it came to that. There was no good reason not to take a second officer, except cost—and since Jefferson had just authorized spending millions of dollars for New Orleans, and he had his whole heart and mind invested in the Lewis expedition, he wasn’t going to let cost be a factor.

Jefferson opened the coffers of the War Department for Lewis, acting in his capacity as commander-in-chief in support of an expedition sanctioned by Congress. In the process, he stretched the Constitution considerably, but penny-pinching the expedition was worse than bending his strict constructionist principles. He told the War Department to pay Lewis an eighteen-month advance in his salary, possibly for land speculation or to pay off debts; Lewis also borrowed $108 from Jefferson.6 Secretary of War Henry Dearborn had sent an order to Harpers Ferry to supply anything Lewis requested in the way of arms and ironwork, “with the least possible delay.” Jefferson saw to it that Lewis had unlimited purchasing power; the chief clerk of the War Department received orders to “purchase when requested by [Lewis] such articles as he may have occasion for, which he has not been able to obtain from the public Stores,” and the Treasury Department was ordered to turn over a thousand dollars for Lewis’s goods.7 Even with some smoke-and-mirrors bookkeeping, the cost overrun was now at 100 percent, and growing daily.

Making the selections took time. Jefferson had hoped that Lewis would be off by June 28, or even earlier, but the day came and went and Lewis still had much to do. Nevertheless, Lewis expected to be on the Missouri by September 1, which would give him two traveling months, during which he hoped to go seven or even eight hundred miles up the Missouri, before going into winter quarters.8

•

On June 29, Dearborn ordered the army paymaster to give Lewis $554, “being six Months pay for one Lieutenant, one Sergeant, one corporal, and ten Privates.”9

That amounted to Lewis’s official authorization to add an officer. Lewis had already acted on it, because Jefferson had agreed within a day or so of Lewis’s arrival in Washington that it had to be done. On June 19, Lewis had written to William Clark. The letter contained what Donald Jackson described as “one of the most famous invitations to greatness the nation’s archives can provide.”10

It is a critical document. It launched one of the great friendships of all time and started the friends on one of the great adventures, and one of the great explorations, of all time.

It is also revealing. Lewis and Clark have become so entwined by history that for many Americans the name is Lewisandclark, but in 1803 they were not intimate friends. Although Clark was born in Virginia four years earlier than Lewis, he had moved to Kentucky as a small boy. They knew each other only in the army, for six months, when Lewis had served under Clark. No ancedotes survive, or any correspondence between them in the next decade except for a business letter from Lewis to Clark, asking him to make inquiries about land in Ohio.

But in that six months together they had taken each other’s measure. That they liked what they saw is obvious from Lewis’s letter to Clark, and Clark’s response. They complemented each other. Clark was a tough woodsman accustomed to command; he had been a company commander and had led a party down the Mississippi as far as Natchez. He had a way with enlisted men, without ever getting familiar. He was a better terrestrial surveyor than Lewis, and a better waterman. Lewis apparently knew of his mapmaking ability. In general, in areas in which Lewis was shaky, Clark was strong, and vice versa.

Most of all, Lewis knew that Clark was competent to the task, that his word was his bond, that his back was steel. Clark knew the same about Lewis. Their trust in each other was complete, even before they took the first step west together. How this closeness came about cannot be known in any detail, but that it clearly was there long before the expedition cannot be doubted.

•

Clark had retired from the army in 1796, partly for reasons of health, partly to try his hand in business, mainly to do something to help straighten out the terribly tangled financial affairs of his older brother, General George Rogers Clark. He was living in Clarksville, Indiana Territory, when Lewis’s letter arrived.

Lewis opened his invitation thus: “From the long and uninterupted friendship and confidence which has subsisted between us I feel no hesitation in making to you the following communication.” He described the origins of the expedition, the congressional action, what he had done in Harpers Ferry and Philadelphia to get ready, and his intention to set out for Pittsburgh at the end of June. He thought he would be in Clarksville to meet Clark about August 10. On the way, he intended to “find and engage some good hunters, stout, healthy, unmarried men, accustomed to the woods, and capable of bearing bodily fatigue in a pretty considerable degree: should any young men answering this discription be found in your neighborhood I would think you to give information of them on my arivall at the falls of the Ohio.”

Lewis described the expedition in matter-of-fact language that may well have left Clark breathless: “My plan is to descend the Ohio in a keeled boat thence up the Mississippi to the mouth of the Missourie, and up that river as far as it’s navigation is practicable with a keeled boat, there to prepare canoes of bark or raw-hides, and proceed to it’s [the Missouri’s] source, and if practicable pass over to the waters of the Columbia or Origan River and by descending it reach the Western Ocean.”

Lewis wrote that he would return to the United States on a trading vessel, if possible. He gave Clark a summary of his instructions from Jefferson, and described the instruments he had collected for making observations.

To carry out the mission, Lewis said he had authorization from Jefferson to pick noncommissioned officers and men, not to exceed twelve, from the western army posts. He added that he was also authorized “to engage any other man not soldiers that I may think useful in promoting the objects of succes of this expedition.” He had in mind hunters, guides, and interpreters.

“Thus my friend,” Lewis concluded, “you have a summary view of the plan, the means and the objects of this expedition. If therefore there is anything under those circumstances, in this enterprise, which would induce you to participate with me in it’s fatiegues, it’s dangers and it’s honors, believe me there is no man on earth with whom I should feel equal pleasuure in sharing them as with yourself.”

Lewis wrote that he had talked with Jefferson about the offer and that the president “expresses an anxious wish that you would consent to join me in this enterprise.” There followed the most extraordinary offer. “He [Jefferson] has authorized me to say that in the event of your accepting this proposition he will grant you a Captain’s commission which of course will intitle you to the pay and emoluments atached to that office and will equally with myself intitle you to such portion of land as was granted to officers of similar rank for their Revolutionary services; your situation if joined with me in this mission will in all respects be precisely such as my own.”

It was remarkable for Lewis to propose a co-command. He did not even have to add a lieutenant to the party, and most certainly did not have to share the command. Divided command almost never works and is the bane of all military men, to whom the sanctity of the chain of command is basic and the idea of two disagreeing commanders in a critical situation is anathema. But Lewis did it anyway. It must have felt right to him. It had to have been based on what he knew about Clark, and what he felt for him.

Lewis wanted Clark along, even if not as an official member of the party. He closed his letter by saying that, if personal or business or any other affairs prevented Clark from accepting, Lewis hoped that he could “accompany me as a friend part of the way up the Missouri. I should be extremely happy in your company.”11

It would take a month for Lewis’s letter to reach Clark, another ten days for his reply to arrive. Meanwhile, a mystery. Ten days after Lewis made his offer of a shared command to Clark, he received from Secretary Dearborn the advance pay for the party to be recruited. It authorized one lieutenant only. Lewis made no known protest. Jefferson should have been alert enough to notice that Dearborn was thinking lieutenant while Lewis was offering captain, and he should have corrected the situation by telling Dearborn that Lewis’s offer would prevail and Clark, if he accepted, would be a captain. But the commander-in-chief did nothing. It was uncharacteristic of Lewis and Jefferson to miss a detail of any kind, much less one fraught with such potential danger for embarrassment, misunderstanding, and bad feeling, but they missed this one.

•

Lewis spent the last week of June buying supplies and instruments, gathering more books, and going over maps. He made arrangements for a stand-in as his fellow officer, should Clark decline. He chose a man he had met in 1799 and served with, Lieutenant Moses Hooke, and assured Jefferson that Hooke was the best officer in the army, “endowed with a good constitution, possessing a sensible well informed mind, is industrious, prudent and persevering, and with-all intrepid and enterprising.” Lewis didn’t hand out praise easily, and since it was clear that he was ready to cross the continent with Hooke, he obviously meant what he said about Hooke’s superior abilities. But there was no hint of a promotion to captain and a co-command.12 Good as Hooke was, he wasn’t William Clark.

•

By July 2, Lewis was nearing completion of the preparations and about to set off for Pittsburgh. That day, he wrote his mother.

He opened with an apology for not having the time to come home for a visit before departing for the western country, a trip he expected to take about a year and a half. As boys setting off on an adventure are wont to do, he reassured his mother: “The nature of this expedition is by no means dangerous, my rout will be altogether thorugh tribes of Indians who are perfectly friendly to the United States, therefore consider the chances of life just as much in my favor on this trip as I should conceive them were I to remain at home.”

After telling his mother not to worry, he wrote of what being Mr. Jefferson’s choice meant to him: “The charge of this expedition is honorable to myself, as it is important to my Country.”

Then it was back to reassurance: “I feel myself perfectly prepared, nor do I doubt my health and strength of constitution to bear me through it; I go with the most perfect preconviction in my own mind of returning safe and hope therefore that you will not suffer yourself to indulge any anxiety for my safety.”

There followed a series of instructions on the education of Lewis’s half-brother, John Marks. Lewis insisted that John go to the College of William and Mary at Williamsburg, even if land certificates had to be sold to pay the tuition. Given how deeply Virginia planters hated to sell land, Lewis’s priorities show the high value he set on education. After the crash courses he had been put through in Philadelphia, he had reason to wish he had gone to college.

He closed with a wish to be remembered to various members of the family, especially the two youngsters, Mary and Jack. “Tell them I hope the progress they will make in their studies will be equal to my wishes.”13

•

Also on July 2, Dearborn handed Lewis the authorization to select up to twelve noncommissioned officers and privates. He could pick them from the garrisons at the posts at Massac and Kaskaskia, the former on the lower Ohio and the latter on the Mississippi, above the mouth of the Ohio. In separate orders, Dearborn told the commanding officers at the posts to furnish Lewis with every assistance in “selecting and engaging suitable men to accompany him on an expedition to the Westward.” That was a license to raid, sure to be resented by captains about to lose their best men, but Dearborn made it stick. “If any [man] in your Company should be disposed to join Capt. Lewis,” and if Captain Lewis wanted the volunteer, “you will detach them accordingly.”

In addition, Captain Russell Bissell at Kaskaskia was ordered to provide Lewis with the best boat on the post and with a sergeant and “eight good Men who understand rowing a boat.” They would carry baggage for Lewis, to his winter quarters on the Missouri, then descend before the ice closed in. Bissell refused Sergeant Patrick Gass’s request to join the expedition, presumably on the grounds that he couldn’t afford to lose his best noncommissioned officer. Lewis used the authority given him by Dearborn to enlist Gass anyway.14

For the descent of the Ohio, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Cushing provided Lewis with eight recruits from the post at Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In a pouch accompanying the order, Cushing included a couple of dozen letters for Lewis to deliver to officers at the western posts. He asked Lewis, after he reached St. Louis, to send the eight recruits down the Mississippi to Fort Adams. Cushing closed with a nice note: “That your expedition may be pleasant to yourself and advantageous to our Country; and when its toils and dangers are over, that you may enjoy many years of happiness, prosperity and honor, is the sincere wish of, Sir, Your most Obdt. Servt.”15

•

July 4, 1803, the nation’s twenty-seventh birthday, was a great day for Meriwether Lewis. He completed his preparations and was ready to depart in the morning. He got his letter of credit in its final form from President Jefferson. And the National Intelligencer of Washington reported in that day’s issue that Napoleon had sold Louisiana to the United States.

It was stunning news of the most fundamental importance. Henry Adams put it best: “The annexation of Louisiana was an event so portentous as to defy measurement; it gave a new face to politics, and ranked in historical importance next to the Declaration of Independence and the adoption of the Constitution—events of which it was the logical outcome; but as a matter of diplomacy it was unparallelled, because it cost almost nothing.”16

Napoleon’s decision to sell not just New Orleans but all of Louisiana, and the negotiations that followed, and Jefferson’s decision to waive his strict constructionist views in order to make the purchase, is a dramatic and well-known story. It is best described by Henry Adams in his History of the United States in the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson, one of the great classics of American history writing.

Napoleon was delighted, and rightly so. He had title to Louisiana, but no power to enforce it. The Americans were sure to overrun it long before he could get an army there—if he ever could. “Sixty million francs for an occupation that will not perhaps last a day!” he exulted. He knew what he was giving up and what the United States was getting—and the benefit to France, beyond the money: “The sale assures forever the power of the United States, and I have given England a rival who, sooner or later, will humble her pride.”17

For Lewis, what mattered was not how Louisiana was acquired, a process in which he played no role, but that the territory he would be crossing from the Mississippi to the Continental Divide now belonged to the United States. As Jefferson nicely put it, the Louisiana Purchase “lessened the apprehensions of interruption from other powers.”

The Purchase did more for the expedition than relieve it of threats from the Spanish, French, or British. As Jefferson noted, it “increased infinitely the interest we felt in the expedition.”18

When Adams wrote that the Purchase “gave a new face to politics,” he meant that it signified the end of the Federalist Party, which was so shortsighted and partisan that many of its representatives criticized the act. Alexander Hamilton was wise to content himself with remarking that Jefferson had just been lucky. The Purchase, he said, resulted from “the kind interpositions of an overruling Providence.” But a Boston Federalist newspaper did not like the deal at all: it called Louisiana “a great waste, a wilderness unpeopled with any beings except wolves and wandering Indians. We are to give money of which we have too little for land of which we already have too much.” Jefferson was risking national bankruptcy to buy a desert.19

Angry partisanship was the order of the day. Senator John Quincy Adams complained in his diary, “The country is so totally given up to the spirit of party, that not to follow blindfold the one or the other is an inexpiable offence.” But the New England Federalists were putting themselves on the wrong side of history to oppose the Purchase. One denounced it as “a great curse,” and another feared that the Purchase “threatens, at no very distant day, the subversion of our Union.”20

Caspar Wistar of Philadelphia, Lewis’s sometime tutor, got it right. He wrote to congratulate Jefferson “on the very happy acquisitions you have made for our Country. Altho no one here appears to know the extent or price of the cession, it is generally considered as the most important & beneficial transaction which has occurred since the declaration of Independence, & next to it, most like to influence or regulate the destinies of our Country.”21

One immediate effect of the Purchase was to change Lewis’s relationship with the Indian tribes he would encounter east of the Divide. The Indians were now on American territory. Lewis would be responsible for informing them that their Great Father was Jefferson rather than the Spanish and French rulers. Jefferson wanted Lewis to bring them into the trading net of the United States, which meant bringing peace among them and telling the British around the Mandan villages that they were on foreign soil.

By far the most important effect of the Purchase on the expedition was a negative that stemmed from the fact that no one knew what the boundaries of Louisiana were. Napoleon sold Louisiana “with the same extent that it now has in the hands of Spain, and that it had when France possessed it.” The general belief was that Louisiana consisted of the western half of the Mississippi drainage. That meant from the Gulf of Mexico northward to the northernmost tributaries of the Missouri, and from the Mississippi westward to the Continental Divide. But no American, Spaniard, Frenchman, or Briton knew how far north that was. Jefferson, greatly excited by the prospect of adding more northern territory to the Purchase, at once began urging Lewis to explore those northern tributaries, where earlier, in the formal instructions, he had emphasized exploration of the southern tributaries.

Jefferson wanted land. He wanted empire. He reached out to seize what he wanted, first of all by continually expanding the boundaries of Louisiana. Diplomatic historian Thomas Maitland Marshall describes it well: “Starting with the idea that the purchase was confined to the western waters of the Mississippi Valley, Jefferson’s conception had gradually expanded until [by 1808] it included West Florida, Texas, and the Oregon Country, a view which was to be the basis of a large part of American diplomacy for nearly half a century.”22

•

Lewis started out for Pittsburgh on July 5, 1803, the day after the news of the Purchase arrived. Although he was in a good mood, he had a great deal to be worried about. Would Clark accept, or would his health or business commitments prevent him from joining? Had the wagonload of supplies gotten from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh? Had the weapons and other items selected at Harpers Ferry been sent to Pittsburgh? Had he selected the right items, in sufficient quantity? What kind of soldiers would be meeting him in Pittsburgh for the trip down the Ohio? Was the keelboat he had ordered made in Pittsburgh completed?

He had a sense of urgency. Having used up more than a month of good traveling weather, he knew the Ohio River would be falling as summer wore on, knew that he had to get going if he were to have any hope of making any significant distance up the Missouri before the weather closed in. But he still had a great deal to do, in Harpers Ferry and Pittsburgh.

So he could not have been altogether easy in his mind as he turned his horse’s head west and started out. But he must have had a joy in his heart. He certainly had a determination: with that first step west, he intended never to look back until he had reached the Pacific.

•

Lewis got to Fredericktown (present Frederick), Maryland, the evening of July 5. There was good news: the wagon carrying supplies from Philadelphia had passed through Fredericktown ten days earlier. There was bad news: on arrival at Harpers Ferry, the driver had decided the arms and other weapons Lewis had ordered were too heavy for his team, so he had gone on to Pittsburgh without them. Lewis hired a teamster in Fredericktown, who promised he would be in Harpers Ferry by July 8. Lewis pushed on to Harpers Ferry, where “I shot my guns and examined the several articles which had been manufactered for me at this place; they appear to be well executed.” What pleased him most was the completed iron-frame boat.

But good feelings gave way to worries—the teamster “disappointed me.” Lewis hired another, locally; the man promised to load up the guns and the iron-frame and the rest and be on his way to Pittsburgh early the next morning. Lewis then set off for Pittsburgh, where he arrived at 2:00 p.m. on July 15.23 He immediately wrote a report to Jefferson, so as to catch the 5:00 p.m. post. It had been hot and dry, the roads “extreemly dusty, yet I feel myself much benifitted by the exercise the journey has given me, and can with pleasure anounce, so far and all is well.” Though the Ohio was low, it could be navigated if he could get a quick start. He had not yet had time to see the boat he had ordered.24

The boat contract called for completion on July 20, but, to Lewis’s intense disappointment, the builder wasn’t even close to done. The contractor claimed he had found it difficult to get the proper timber, but now it had arrived, and he promised to have the work completed by July 30. Lewis reported to Jefferson that he was “by no means sanguine” that he could meet that date; August 5 was more like it. “I visit him every day,” Lewis wrote, “and endeavour by every means in my power to hasten the completion of the work; I have prevailed on him to engage more hands. . . . I shall embark immediately the boat is in readiness.”

Some good news: the wagon from Harpers Ferry arrived on July 22. So had the party of seven recruits (the eighth recruit had pocketed his bounty for enlisting and promptly deserted) from Carlisle who would make the descent of the Ohio with the keelboat. But what nagged was the falling river. “The current of the Ohio is extreemly low and continues to decline,” Lewis told Jefferson. “This may impede my progress but shall not prevent my proceeding, being determined to get forward though I should not be able to make a greater distance than a mile pr. day.”25

The next week was agony for Lewis. The boatbuilder was a drinking man, so he seldom worked mornings, and sometimes not in the afternoons either. He had none of Lewis’s sense of urgency. But there was no one else in Pittsburgh capable of doing the work. So Lewis fretted and fumed but did not fire the contractor.

•

On July 29, the mail brought in the best possible news. It was a letter from Clark. He had accepted! “The enterprise &c. is Such as I have long anticipated and am much pleased with,” Clark wrote, “and as my situation in life will admit of my absence the length of time necessary to accomplish such an undertaking I will chearfully join you in an ‘official Charrector’ as mentioned in your letter,I and partake of the dangers, difficulties, and fatigues, and I anticipate the honors & rewards of the result of such an enterprise. . . . This is an undertaking fraited with many difeculties, but My friend I do assure you that no man lives with whome I would perfur to undertake Such a Trip &c. as yourself.”

He asked Lewis to tell Jefferson to send his commission on to Louisville, across the river from Clarksville. He said he would try to find a few good men for the expedition, which he reported was the chief subject of conversation in Louisville.26

In a follow-up letter of July 24, Clark related that “several young men (Gentlemens sons) have applyed to accompany us—as they are not accustomed to labour and as that is a verry assential part of the services required of the party, I am causious in giveing them any encouragement.” He told Lewis he would be ready to go as soon as the keelboat reached Louisville, for he too was eager to get as far up the Missouri as possible that season. “My friend,” he concluded, “I join you with hand & Heart.”27

“I feel myself much gratifyed with your decision,” Lewis told Clark by the next post, August 3, “for I could neither hope, wish, or expect from a union with any man on earth, more perfect support or further aid in the discharge of the several duties of my mission, than that, which I am confident I shall derive from being associated with yourself.”

Lewis said he was pleased that Clark had engaged some men and reminded him that this was their most critical job. The enterprise “must depend on a judicious scelection of our men; their qualifycations should be such as perfectly fit them for the service, outherwise they will reather clog than further the objects in view; on this principle I am well pleased that you have not admitted or encouraged the young gentlemen you mention, we must set our faces against all such applications and get rid of them on the best terms we can. They will not answer our purposes.”28

Clark absolutely agreed. On August 21, he informed Lewis that “I have had many aplications from stout likely fellows but have refused to retain some & put others off with a promis of giveing ‘an answer after I see or hered from you.’ ” Lewis was simultaneously being pestered by young men in Pittsburgh who wanted to join up.

Clearly the word was out in the western country, and what young unmarried frontiersman—whether gentlemen’s sons or the sons of whiskey-making corn farmers—could resist such an opportunity? It was the ultimate adventure. The reward for success would be a land grant, similar to those given the Revolutionary War veterans—a princely reward to frontiersmen.

So Lewis and Clark could be highly selective. Clark was an excellent judge of men. He had gathered seven of “the best young woodsmen & Hunters in this part of the Countrey”—these were the men awaiting Lewis’s approval before being accepted. They included Charles Floyd, Nathaniel Pryor, William Bratton, Reubin Field, Joseph Field, George Gibson, and John Shields. Lewis was equally good as a judge; in Pittsburgh, he selected John Colter and George Shannon (at eighteen, the youngest of the group), subject to Clark’s approval.

•

The boatbuilder was guilty of “unpardonable negligence,” Lewis charged. August 5 came and went and only one side of the boat was partially planked. In desperation, Lewis thought of purchasing two or three pirogues. It is impossible to tell what he meant by this, as he used the words “pirogue” and “canoe” interchangeably. A pirogue is a flat-bottomed dugout, designed for marshes and shallow waters, most popular today among Louisiana duck-hunters. The pirogues Lewis had in mind, however, were much larger (and possibly not dugouts at all, but big flat-bottomed, masted rowboats built from planks). A canoe is a round- or curved-bottom craft, either dug out of the trunk of a large tree, or built to a frame and covered with bark or skins, most popular today for recreation on large, fast rivers. When Lewis said “canoe,” however, what he meant was a round-bottomed dugout much larger than today’s sporting canoes.

In his anxiety to get going, and with his doubts that the boatbuilder would ever complete the keelboat, Lewis was proposing to descend the Ohio River in pirogues until he could find a keelboat somewhere downriver to purchase. But when the local merchants told him there was no place to procure a boat below, and the boatbuilder promised to be done by August 13, Lewis abandoned the fantasy and waited and fumed.

Four days later, the builder got drunk and quarreled with his workmen, several of whom quit on the spot. Lewis threatened him with a canceled contract, but there wasn’t much reality to the threat: the boatbuilder had no competition within hundreds of miles. The builder did give a promise of greater sobriety, but this lasted less than a week. Lewis charged that he was “continuing to be constantly either drunk or sick.” Lewis spent most of his time at the work site, “alternately persuading and threatening.” He soothed himself some by buying a dog and naming it Seaman. He paid twenty dollars for the Newfoundland, a large black dog.

Each day the river sank a bit lower. It got so bad that Lewis was told “the river is lower than it has ever been known by the oldest settler in this country.”29

•

The delays all but drove him mad, but they had to be endured, because the job had to be done right. After all, Lewis was proposing to descend the Ohio, then ascend the Mississippi to the mouth of the Missouri, then ascend the Missouri to the Mandan villages in that boat. A lot of thought had gone into it, requiring skilled woodworking; the complexity of the thing must have been some part of the cause of the delay.II

Lewis had designed it, and he oversaw its construction and probably made modifications in the plans as the work progressed. It was basically a galley, little resembling the classic keelboat of the West. It seems to have been the standard type of vessel for use on inland waters at the outset of the nineteenth century, especially for military purposes. Lewis probably had been on a similar keelboat on the Ohio when he was a paymaster.

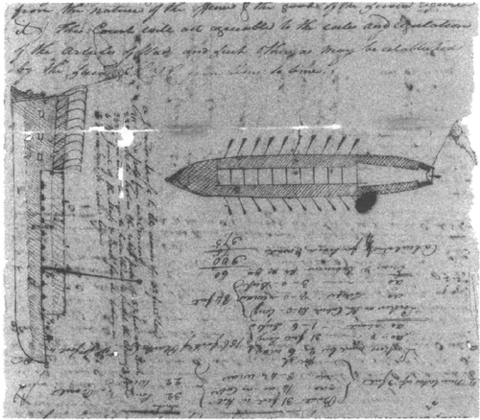

Clark’s sketch of the keelboat, from his field notes, January 21, 1804. (Beinecke Library, Yale University)

It was fifty-five feet long, eight feet wide at midships, with a shallow draft. It had a thirty-two-foot-high mast that was jointed near the base so it could be lowered. The mast could support a large square sail and a foresail. A ten-foot-long deck at the bow provided a forecastle. An elevated deck of ten feet at the stern accommodated a cabin. The hold was thirty-one feet in length and could carry a cargo of about twelve tons. Crossing the deck were eleven benches, each three feet long, for use by two oarsmen.

The boat could be propelled by four methods: rowing, sailing, pushing, and pulling. In pushing, the crew set long poles in the river bottom and pushed on them as they walked front to rear on the boat. Men or horses or ox used ropes for pulling, sometimes from the water, sometimes from the shore.30

To hurry the builder along, Lewis tried getting on his knees, he tried shouting and cursing, “but neither threats, persuasion or any other means which I could devise were sufficient to procure the completion of the work sooner than the 31st of August.”

He had hoped to be on his way on by July 20, at the latest by August 1. By the time the boat was ready, the river had fallen so low that “those who pretend to be acquainted with the navigation of the river declare it impracticable to descend it.” Lewis was going anyway.31

How anxious he was to get going he demonstrated on the morning of August 31. The last nail went into the planking at 7:00 a.m. By 10:00 a.m., Lewis had the boat loaded. To keep it as high in the water as possible, he shipped a considerable quantity of goods by wagon to Wheeling. In addition, he purchased a pirogue to carry as much as possible, to further lighten the load. He intended to purchase another at Wheeling to carry the goods coming by land. Then he was on his way.

I. Here Clark first wrote “on equal footing &c.,” then crossed it out and substituted “as mentioned in your letter.”

II. It took a dozen or more volunteers in Onawa, Iowa, more than sixty working days to build a replica in the late 1980s, using power tools.