It was always cold, often brutally cold, sometimes so cold a man’s penis would freeze if he wasn’t quick about it.

Lewis kept a weather diary, in which he faithfully recorded the day’s temperature at sunrise and at 4:00 p.m., as well as the conditions—fair, cloudy, snow, hail, and “c.a.r.s.” to indicate “cloudy after rain and snow”—wind direction and force, and the rise and fall of the river. This was the first collection of weather data from west of the Mississippi River.

It recorded a somewhat colder winter than the norm during the thirty-year period 1951–80, when December, January, and February temperatures averaged 12.3 degrees above zero. In 1804–5, it averaged 4 degrees above zero for December, 3.4 degrees below for January, and 11.3 degrees above for February, or an average for the winter of 4 degrees above zero.1

The Indians could take it. On various occasions, the Americans would hear of or meet Indians who had spent the night out on the prairie, without a fire and with only a buffalo robe to cover them, and only thin moccasins and antelope leggings and shirt to wear, and hardly suffer from it. On January 10, 1805, Clark reported two such incidents and commented, “Customs & the habits of those people has ancered to beare more Cold than I thought it possible for man to indure.”

The river was frozen solid enough so that great herds of buffalo could cross without breaking through. Lewis wanted to pull the keelboat on shore for repairs, but it was locked into the ice. Beginning on February 3, he tried various expedients to free it—chipping it out with axes, freeing it by means of boiling water and hot stones, or cutting it loose with “a parsel of Iron spikes.” At each attempt, he had a windlass and a large rope of elk skin ready to haul her up on the bank when freed from the ice. But it took weeks to break her free. Not until February 26 did the party finally get the boat out of the water. Why they didn’t pull the boat out before the river iced over neither of the captains ever bothered to explain.

Such extreme cold, one might have thought, would have induced the captains and the men to spend the winter in a state of semihibernation, seldom venturing away from their fires or out of their huts, which Ordway described as “warm and comfortable.”2 But the captains kept the men busy, both because there was lots of real work that had to be done and because they were good officers who knew for a certainty that an idle soldier is a bored soldier heading for trouble.

Larocque, MacKenzie, and other British traders could have told the captains about the troubles at Hudson’s Bay Company and North West Company posts during the winter, the trappers shut up in their huts, small smoky rooms illuminated only by candlelight. Such conditions led to bad temper, fistfights, ill-will, and lack of discipline.

But the Corps of Discovery was not a wandering band of trappers; it was an infantry company of the U.S. Army. Still, Clark and Lewis had seen plenty of trouble at Wood River the previous winter, and, bad as the weather had been in Illinois, it was nothing compared with North Dakota.

Yet at Fort Mandan there were no fights, no desertions. The worst infraction was relatively minor. On February 9, Private Thomas Howard got back to the fort after dark. Rather than call out to the guard to have the gate opened, he scaled the wall. Unfortunately for Howard, an Indian was looking on and shortly thereafter climbed the wall himself. The guard reported these doings to Captain Lewis.

Lewis was much alarmed. Although relations with the Mandans were excellent, they were not so good with the Hidatsas, and in any case the Mandans might decide at any moment to take advantage of their overwhelming numbers, overpower the expedition, and help themselves to the treasure trove of rifles, kettles, trade goods, and the rest. Private Howard’s thoughtless act had just revealed to the Indians how easy it was to scale the wall.

Lewis’s first thought was to leave Howard until later and deal with the threat immediately, by convincing the Indian who had followed him over the wall that what he had done was a bad idea. He had the man brought to him. “I convinced him of the impropryety of his conduct,” Lewis recorded, “and explained to him the riske he had run of being severely treated, the fellow appeared much allarmed, I gave him a small piece of tobacco and sent him away.”

Then he turned to Private Howard. He had Howard put under arrest and ordered him tried by a court-martial. Lewis was not inclined to be lenient, because “this man is an old soldier which still hightens this offince.”

In the morning, Howard was charged with “Setting a pernicious example to the Savages.” He was found guilty and sentenced to fifty lashes, a heavy punishment for an offense that amounted simply to thoughtlessness. Perhaps for that reason, the court recommended mercy, and Lewis forgave Howard the lashing. That was the only court-martial held at Fort Mandan, and the last on the entire expedition.

•

The garrison at Fort Mandan maintained regular military security, with drills, sentry-posting, challenges, daily inspection of the weapons, and the rest. When the temperature went well below zero, sentries were replaced every half-hour. Aside from the possibility of a hostile move by Mandans and Hidatsas, the Sioux were definitely hostile and not so far away that they couldn’t stage a raid, and the Arikaras might join them. So the expedition stayed constantly on guard.

The Sioux did make a raid, in mid-February. Clark had gone out on a nine-day hunt with a large party of men. The hunters killed more meat than they could transport. When Clark got back to Fort Mandan, he dispatched Drouillard with three men and three horse-drawn sleighs to retrieve the carcasses. A band of Sioux warriors spied the small party.

Clark’s description of what happened next, based on Drouillard’s testimony, tantalizes rather than satisfies our curiosity about how it went: “About 105 Indians rushed on them and Cut their horses from the Slays two of which they carried off in great hast, the 3rd horse was given up to the party [by the Indians, for] fear of some of the Indians being killed by our men who were not disposed to be Robed of all they had tamely.”

However determined the party, the Indians got away with the two sleighs and two knives. However bold the Indians, they were forced to give back a tomahawk and one horse and sleigh. So the Americans didn’t do too badly, given that the encounter pitted 105 warriors against four men—Drouillard, Privates Robert Frazier and Silas Goodrich, and Newman, who was not allowed to carry a weapon.

At the end of November, Clark had led a party to punish the Sioux and Arikaras for attacking the Mandans. This time it was Lewis’s turn to go on the warpath. He set out at sunrise, February 15, at the head of twenty-four volunteers, including a few Mandan warriors coming along as allies, to find and punish the Sioux. But the weather was bad, the snow was deep, and the men soon had their feet cut and bleeding on the sharp ice. The Mandans told Lewis the trail was cold and the cause hopeless, and they abandoned the search.

Lewis, always persistent, doggedly kept on, covering thirty miles before he discovered two abandoned tepees. Thoroughly exhausted, the party slept in them. The next day, Lewis finally abandoned the search and instead went hunting. The party stayed out all week and brought back more than a ton of meat (thirty-six deer, fourteen elk).3

•

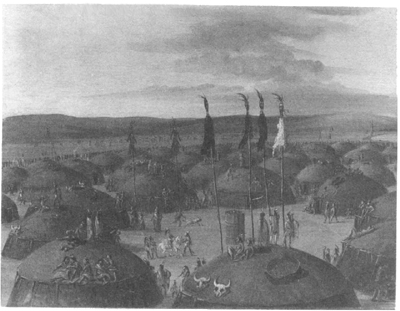

Encounters with the Mandans were altogether different. The neighbors got along just fine. The chiefs and captains, warriors and men called on one another, went hunting together, traded extensively, enjoyed sexual relations with the same women on a regular basis, joked, and talked—as best they could through the language barrier—about what they knew. They managed to describe wonders to one another, using their hands to illustrate their points, drawing maps, mountains, or wooden houses on the dirt floor of the lodge, educating one another. The Mandans and the Hidatsas knew something of the country to the west and were glad to share their knowledge with the captains; the Americans knew the country to the east of the Mississippi River and were eager to induce some Mandan and Hidatsa chiefs to make the journey to Washington.

Holidays and special occasions brought the red and white men closer together. On New Year’s Day, 1805, half the detachment went to the lower Mandan village, at the particular request of the chief, to dance to the music of a tambourine, a sounding horn, and Private Cruzatte’s fiddle. The Indians enjoyed the music and the dancing, especially the Frenchman, who danced on his hands.

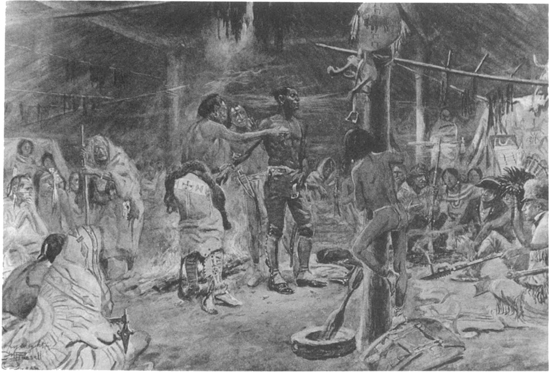

York, watercolor (1908) by Charles M. Russell. A Mandan chief, suspicious of York’s color, is trying to rub it off. (Montana Historical Society)

George Catlin, Bird’s-Eye View of the Mandan River (1837–39). (National Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C./Art Resource, N.Y.)

Toward noon, Clark and York arrived at the village, where festivities were in full swing. Clark called on York to dance, “which amused the croud verry much, and Some what astonished them, that So large a man Should be so active.”

The following day, it was Lewis’s turn. He led the party of musicians and dancers to the second Mandan village, for more of what Sergeant Ordway called “frolicking.”4

From January 3 to 5, the Mandans held a nightly dance of their own. They invited the garrison to join them. When the men arrived, they were ushered to the back of the communal earth lodge. The dance began. To the music of rattles and drums, the old men of the village, dressed in their finery, entered the lodge, gathered into a circle, sat down, and waited. Soon the young men and their wives filed in, to take their places at the back of the circle. They fixed pipes for the old men, and a smoking ceremony ensued.

As the drumbeat became more insistent and the chanting swelled, one of the youngsters would approach an old man and beg him to take his wife, who in her turn would appear naked before the elder. She would lead him by the hand and—but let Clark tell it, as only he can: “the Girl then takes the Old man (who verry often can Screcely walk) and leades him to a Convenient place for the business, after which they return to the lodge.”

In the event that the old man failed to gratify the wife, the husband would offer her again and again, and throw a robe into the bargain, and beg the old man not to despise the couple.

“All this,” Clark noted, “is to cause the buffalow to Come near So that They may kill them.” In the winter, the herds migrated far and wide in search of windblown bare spots where they could get at the grass. The buffalo dance was thought to be a magnet to the wandering herds.

There was a second purpose to the dance. The Mandans believed that power—in this case, the hunting abilities of the old men—could be transferred from one man to another through sexual relations with the same woman. To the great good luck of the enlisted men, the Mandans attributed to the whites great powers and big medicine. So, throughout the three-day buffalo dance, the Americans were said to be “untiringly zealous in attracting the cow” and in transferring power. One unnamed private made four contributions.5 Sure enough, there was a good buffalo hunt a few days later.

Much about the Mandans was curious or inexplicable. Lewis was especially struck by their treatment of their horses. When some Mandan ponies on loan to the Americans arrived at the fort late on February 12, they appeared “so much fatieged” that Lewis ordered them fed corn moistened with a little water, “but to my astonishment found that they would not eat it but prefered the bark of the cotton wood which forms the principall article of food usually given them by their Indian masters in the winter season.”

The Mandans, according to Lewis, “are invariably severe riders, and frequently for many days in pursuing the Buffaloe they [the horses] are seldom suffered to tast food.” After the hunt, the Indians brought their horses into their lodges for the night, where the animals were given what Lewis regarded as “a scanty allowance” of cottonwood ranging from the size of a man’s finger to that of his arm. Lewis could hardly believe that a horse could exist long under such circumstances, but he had seen with his own eyes and knew it to be a fact that the Mandan horses “are seldom seen meager or unfit for service.”

•

Lewis’s long essay on Mandan horsemanship was the last in a series of ten journal entries he made beginning on February 3. That was the day Clark set out with sixteen men on a nine-day hunting expedition. In no way does Lewis indicate that because Clark was gone from Fort Mandan it had become his responsibility to keep up the journal, but since the Lewis journal stopped when Clark returned, it seems likely that is what happened. If so, Lewis was not keeping a regular journal in the winter of 1804–5, although he was doing a great deal of writing in the form of reports to Jefferson.

•

He was also doing a good deal of doctoring. On the first day of winter, a Mandan woman brought her child to Lewis, showed him an abscess on the child’s back, and offered Lewis as much corn as she could carry for some medicine to cure the sore. Lewis complied. On January 10, a thirteen-year-old Mandan boy came to the fort with frozen feet. The captains used a standard treatment, soaking the feet in cold water. It appeared to work (it did with the men, who had frequent cases of frozen toes and fingers but always recovered). In this case, however, the boy was too far gone. On January 26, Clark recorded that “Capt. Lewis took off the Toes of one foot of the boy who got frost bit Some time ago.”

Dr. E. G. Chuinard, whose medical history of the expedition all Lewis and Clark scholars turn to when the subject is doctoring, comments: “Probably the necrotic tissue had demarcated in the two weeks since his toes were frozen, and probably the amputations done by Lewis consisted of plucking loose the dead tissue, possibly disarticulating the joints, and possibly having to sever tendons.”6

Five days later, the captains “sawed off the boys toes” from the other foot. How it was done, they don’t say. Dr. Chuinard notes that a surgical saw was not listed in the medical kit and speculates that one of the two handsaws was used.7 However it was done, more than three weeks later, on February 23, Clark reported, “The father of the Boy whose feet were frozed near this place, and nearly Cured by us, took him home in a Slay.”

Aside from frozen skin and extremities, the most common medical problem the captains faced was syphilis. Few details come down in the journals, but it is possible that nearly every man suffered from the disease. As for the captains, they never mention taking the standard treatment themselves.

That treatment consisted of ingesting mercury, in the form of a pill called calomel (mercurous chloride). The side effects of mercury could be dangerous; the phrase “mad as a hatter” referred to hatmakers who used mercury in the process of their work and became a bit crazy from breathing in all those fumes. But it was sovereign for syphilis, and Lewis knew this and administered it routinely.8

The captains applied all their treatments on the principle that more is better. On January 26, one of the men was “taken violenty Bad with the Plurisee.” How he survived the captains’ treatment is a wonder. They bled him, purged him with Rush’s pills, and greased his chest (which might actually have done some good). He was still suffering the next day, so Clark bled him again and then put him into a sweat lodge, where water was splashed onto hot rocks to produce a sauna—and that must have done some good, for the patient is not again mentioned.

Lewis’s most unusual experience as a doctor came on February 11, when he was present at the labor of one of Charbonneau’s wives, Sacagawea. Lewis noted that “this was the first child which this woman had boarn and as is common in such cases her labour was tedious and the pain violent.” Lewis worried about her, because he was counting on her as a translator with the Shoshone Indians (known by Lewis to be rich in horses) when he got to the mountains. He consulted with Jessaume, who said that in such cases it was his practice to administer a small portion of the rattle of the rattlesnake. According to Jessaume, it always worked.

“Having the rattle of a snake by me,” Lewis wrote in his journal, he broke the rattles into small pieces and mixed them with some water, which Sacagawea then drank. “Whether this medicine was truly the cause or not I shall not undertake to determine,” Lewis said, “but she had not taken it more than ten minutes before she brought forth.” In a sentence itself pregnant with hope but tempered by a skepticism befitting a scientist of the Enlightenment, Lewis wrote, “This remedy may be worthy of future experiements, but I must confess that I want faith as to it’s efficacy.”

The baby, a boy named Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, was healthy and active. The family had its own hut inside Fort Mandan, so the cries of a hungry infant rang through the parade ground and surely caused at least some pangs of homesickness among at least a few of the men, as they remembered their own families and their own little brothers or sisters. Siblings were very much on Lewis’s mind. In a long letter to his mother about this time, he gave over a special section to his siblings.

Charbonneau, the new father, was all set up by what he had done and was coming to have a wholly new view of his own importance. Quite probably this escalation in self-importance was fed by the conversations he translated through the winter between the captains and the Indians. From the captains’ questions about what lay out west, and the Indians’ answers, Charbonneau knew that Sacagawea was critical to dealing with the Shoshones. And without Charbonneau, no Sacagawea.

So, on March 11, when the captains sat down with Charbonneau to make a contract, it was Charbonneau who took the high ground and tried to dictate the terms. The captains said he would have to pitch in and do all the work the enlisted men had to do and would have to stand a regular guard. Charbonneau replied that “let our Situation be what it may he will not agree to work or Stand a guard.” There was more: “If miffed with any man he wishes to return when he pleases, also have the disposial of as much provisions as he Chuses to Carry.”

“In admissable,” Clark and Lewis flatly declared. They told Charbonneau to move out of the fort, taking his family with him, and they hired Mr. Gravelines as interpreter.

After four days of living in the Mandan village, Charbonneau sent a message to the captains via one of the Frenchmen “to excuse his Simplicity and take him into the cirvise.” Did he come to his senses on his own? Or did the Frenchmen tell him what a fool he was, what a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity he was passing up? Or was it Sacagawea who said she absolutely had to go see her people and participate in this great adventure? However it happened, Charbonneau was ready to crawl.

The captains sent word for him to come to the fort for a discussion. He showed up on March 17. “We called him in,” Clark reported, “he agreed to our terms and we agreed that he might go on with us &c &c.”

The roster for the expedition was complete. The permanent party that was getting ready to head west consisted of the three squads of enlisted men, each with its sergeant, plus the two captains, and five persons from outside the military establishment, namely Drouillard, York, Charbonneau, Sacagawea, and Jean Baptiste (nicknamed “Pomp” or “Pompey” by Clark).

•

By February 4, Lewis noted in his journal, the expedition had about run out of meat. That morning, Clark set out on his hunting expedition. The next day, Lewis reported that the immediate problem of scanty provisions had been overcome, although not with meat but with corn, and thanks to a bellows rather than a rifle.

Private John Shields was a skilled blacksmith. He had set up for business at the expedition’s forge and bellows inside the fort. There he mended iron hoes, sharpened axes, and repaired firearms for the Indians in exchange for corn. But by the end of January, business was turning sour. The market for mending hoes had been satisfied. Shields needed some new product to attract business.

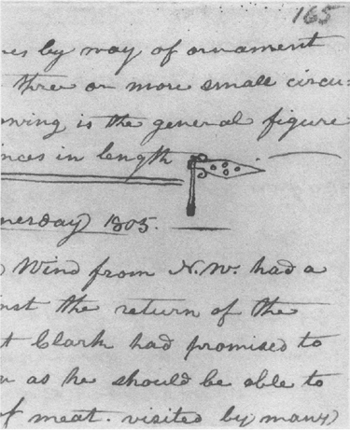

The arms trade was the obvious answer. Not in firearms—the captains turned away all requests for rifles or pistols—but in battle axes. There was a particular form of battle ax highly prized by the Indians and easily made by Shields. Lewis disapproved of the design, writing that it was “formed in a very inconvenient manner in my opinion.” The blade was too thin and too long, the handle too short, the overall weight too little, all of which combined to make a weapon that made “an uncertain and easily avoided stroke.”

Battle-ax, sketch by Lewis, in his journal. (Courtesy American Philosophical Society)

But arms merchants give the customer what he wants. Shields went to work, getting his sheet iron from an all-but-burned-out stove. Some of the men were detailed to cutting timber to provide wood to make a charcoal kiln, to expand production capacity. Still, the Americans couldn’t turn out battle axes fast enough.

The Indians were skilled traders who drove hard bargains. On February 6, Lewis had Shields cut up what was left of the stove into pieces of four inches square, which could then be worked into arrow points or buffalo-hide scrapers. After some haggling, a price was set: seven to eight gallons of corn for each piece of metal. Each side thought it had made a great bargain.I

In his February 6 journal entry, Lewis paid tribute to Shields and his helpers: “The blacksmiths take a considerable quantity of corn today in payment for their labour. the blacksmith’s have proved a happy resoce to us in our present situation as I believe it would have been difficult to have devised any other method to have procured corn from the natives.”

•

Lewis gave the full credit to Shields when he might well have split it, giving at least some to the Indians for having the corn available in the first place. Working as hard as they did in such extreme cold weather, the men ate prodigiously, six thousand calories or even more per day. A modern athlete seldom consumes more than five thousand, but the calories the men were getting in 1805 contained very little, if any, fat. Consequently, no matter how much they ate, the men were always hungry.9 It was Mandan corn that got the expedition through the winter. Had the Mandans not been there, or had they had no corn to spare, or had they been hostile, the Lewis and Clark Expedition might not have survived its first winter.

Lewis never put it that way and in fact probably never thought of it that way. Two days after writing the passage praising Shields for procuring corn, Lewis had a visit from the chief of the upper Mandan village, Black Cat. Lewis had been with him in Black Cat’s village on January 2 and other occasions. This was Black Cat’s seventeenth visit to Fort Mandan. He brought presents, including a fine bow. Lewis gave him some fishing hooks and some ribbon. Black Cat’s squaw gave Lewis two pairs of handsome moccasins; he gave her a mirror and a couple of needles. Black Cat stayed to dine at the captains’ quarters.

That evening, Lewis wrote in his journal, “This man possesses more integrety, firmness, inteligence and perspicuety of mind than any indian I have met with in this quarter, and I think with a little management he may be made a usefull agent in furthering the views of our government.”

A remarkable sentence. In the first half, Lewis obviously was speaking from the heart. Clearly he enjoyed being with and greatly respected Black Cat. Yet, in the second half of the sentence, he blandly discusses his plans to manage and manipulate his friend for the benefit of the United States.

A further problem is this: what were the views of the Americans? On the one hand, peace. Lewis and Clark always preached peace to the Indians, giving them what the Americans thought of as overwhelmingly powerful reasons to avoid war. On the other hand, the Americans were arms merchants. As James Ronda puts it, “Typical of this dilemma was the request from a war chief who came to purchase an axe and obtain permission to attack Sioux and Arikara warriors. For the proper price in corn the axe was handed over but the request to use it was denied.” The Hidatsa chief must have wondered what sort of man would sell arms to a warrior and then tell him not to engage the enemy.10

•

The winter at Fort Mandan involved hunting, trading, keeping fit, dealing with the cold, doing extensive repairs to old equipment and building new canoes, visiting the Indians, and much more. But for Meriwether Lewis it was primarily a winter of scholarship, of research and writing. For most of the day, most days, he was involved in gathering information or writing down what he had learned. He had endless discussions with the Indians about what lay out west, or what this or that faraway tribe was like. Or he bent over his writing desk in his smoky room, with a candle for illumination, dipped his quill into the inkstand, and wrote for hours on end.

His subject was America west of the Mississippi River. He wrote about what he had seen and learned, and what he had heard. He tried to think like Jefferson, to anticipate what the president would want to know or to guess how the president would present this or that subject.

•

And what of Jefferson, meanwhile? What did he know about where the expedition was, and how it was doing?

Precious little. He had no direct word from Lewis after the expedition left St. Charles. The Osage chiefs whose visit Lewis had arranged arrived in Washington in July 1804. In greeting them, Jefferson spoke of his “beloved man, Capt. Lewis.”11 On January 4, 1805, Jefferson wrote Lewis’s brother, Reuben, to report that he had just learned (apparently by word-of-mouth via a trapper who had returned to St. Louis that fall) that on August 19 the expedition was near the mouth of the Platte. According to the report, “No accident had happened & he [Lewis] had been well received by all the Indians on his way. It was expected that he would winter with the Mandans, 1300 miles up the river.”

Jefferson predicted that the expedition would reach the Pacific during the coming summer, then return to the Mandan villages for the winter of 1805–6. “If so,” the president cheerfully concluded, “we may expect to see him in the fall of 1806.”12

I. How popular those axes were among the Indians, and consequently how far they traveled across the trade routes, Shields found out some fourteen months later, when he discovered axes he had made at Fort Mandan among the Nez Percé on the other side of the Rocky Mountains.