On the morning of June 3, the party crossed the Missouri and set up a camp on the point formed by the junction of the two large rivers. “An interesting question was now to be determined,” Lewis wrote in his journal: “Which of these rivers was the Missouri?”

It was a difficult as well as a critical call. According to the Hidatsas, the Missouri ran deep into the Rocky Mountains to a place where it approached to within a half-day’s portage of the waters of the Columbia River. So far, their description of the Missouri had been accurate. But they had said nothing about a river coming in from the north after passing Milk River. How could they have missed this one? But they had also said nothing about a great river coming into the Missouri from the south. That the Indians had not mentioned such a river “astonishes us a little,” Lewis wrote.I

Jefferson’s orders were explicit: “The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river.” The Hidatsas were explicit: the Missouri River had a Great Falls as it came out of the mountains, after which it penetrated those mountains almost to the Continental Divide, at which place lived the Shoshone Indians, who had horses, essential to getting over the Divide, and whose language Sacagawea spoke as her native tongue.

The right-hand or north fork came in on an almost straight west-east line, meaning that going up that river was heading directly toward the mountains. The left-hand or south fork came in from the southwest. The right fork was 200 yards wide, the left fork 372. The right fork was deeper, but the left fork’s current was swifter. Lewis described the north fork as running “in the same boiling and roling manner which has uniformly characterized the Missouri throughout it’s whole course so far; it’s waters are of a whitish brown colour very thick and terbid, also characeristic of the Missouri.” The water of the south fork “is perfectly transparent” and ran “with a smoth unriffled surface.”

As Lewis suummed it up, “the air & character of this river [the north fork] is so precisely that of the missouri below that the party with very few exceptions have already pronounced the N. fork to be the Missouri; myself and Capt. C. not quite so precipitate have not yet decided but if we were to give our opinions I believe we should be in the minority.”

Lewis reasoned that the north fork had to run an immence distance through the Plains to pick up enough sediment to make it so cloudy and turbid, whereas the south fork must come directly out of the mountains. The bed of the south fork was composed of smooth stones, “like most rivers issuing from a mountainous country,” and the bed of the north fork was mainly mud. He and Clark talked it over, without reaching a precipitate conclusion. “Thus have our cogitating faculties been busily employed all day,” Lewis wrote.II

The captains sent Sergeant Pryor up the north fork to scout; he returned in the evening to report that at ten miles the river’s course turned from west to north. They sent Sergeant Gass up the south fork; he reported that at six and a half miles the river continued to bear southwest. “These accounts being by no means satisfactory as to the fundamental point,” Lewis wrote, “Capt. C. and myself concluded to set out early the next morning with a small party each, and ascend these rivers untill we could perfectly satisfy ourselves. . . . it was agreed that I should ascend the right hand fork and he the left. . . . we agreed to go up those rivers one day and a halfs march or further if it should appear necessary to satisfy us more fully of the point in question. . . . We took a drink of grog this evening and gave the men a dram.”

Lewis packed his “happerst,” or knapsack, and had it ready to swing on his back at dawn. He commented that this was “the first time in my life that I had ever prepared a burthen of this kind” (meaning, apparently, that since his childhood a slave, later an enlisted man or a servant, had carried his backpack), “and I am fully convinced that it will not be the last.”

In the morning, he set off, accompanied by Sergeant Pryor; Privates Shields, Windsor, Cruzatte, and Lepage; and Drouillard. (Lewis was a great admirer of “Drewyer,” calling him “this excellent man.” Whenever Lewis led a small party on a scouting mission, Drouillard was almost always the first man chosen.)

The party ascended the river along its north bank. “The whole country in fact appears to be one continued plain to the foot of the mountains or as far as the eye can reach,” Lewis wrote. The walking was difficult, partly because of the prickly pears, whose thorns readily penetrated the thin moccasins the men were wearing. These low cactus plants were so numerous “that it requires one half of the traveler’s attention to avoid them.” Further, the dry ravines were steep and numerous, so much so they caused Lewis to return to the river and travel through its bottoms. Despite the difficulties, he covered thirty-two and a half miles that day, most of it nearly straight north.

This was the most critical exploration Lewis had ever made. He was in country totally unknown except to the Blackfoot Indians, on a river he had never heard of that went he knew not where. Yet his eye for detail, for what was new, and for what was pleasing, was as sharp as always. He described the grass (short) and the distant mountains (the Bears Paw, the Highwoods, and Square Butte). He saw and wrote descriptions of two birds unknown to science, the long-billed curlew and McCown’s longspur. He camped in a shelter of riverbank willows and got thoroughly soaked from a hard, cold rain, but still concluded his June 4 journal entry, “The river bottoms form one emence garden of roses, now in full bloe.”

The following day, he made another thirty-plus miles upstream, or nearly to present-day Tiber Dam, on a course slightly north of west. He came to the conclusion, as he put it the next day, “that this branch of the Missouri had it’s direction too much to the North for our rout to the Pacific.” He made two discoveries: Richardson’s ground squirrel and the sage grouse.

He decided to make camp, and at noon the next day make an observation of the sun in order to fix the latitude of the place, in the hope that he was north of forty-nine degrees of latitude. But at noon on June 6, the sky was overcast, “and I of course disappointed in making the observation which I much wished.” His sense that he was at the northernmost point yet in the journey was correct, but he was not as far north as he hoped. Tiber Dam is about forty miles short of the forty-ninth parallel.

He had the men build two rafts to descend the river, but the craft proved too small for the task (one man almost lost his rifle), so “we again swung our packs” and set out over the plains. It was cold, rainy, miserable. The party made twenty-five miles that afternoon. Lewis closed his journal entry, “It continues to rain and we have no shelter, an uncomfortable nights rest is the natural consequence.”

It rained all night, “and as I expected we had a most disagreable and wrestless night.” At dawn “we left our watery beads” and proceeded downstream, but only with the greatest danger, because the wet clay was “precisely like walking over frozan grownd which is thawed to small debth and slips equally as bad.”III In passing along the face of a bluff, Lewis slipped at a narrow walkway of some thirty yards in length across a bluff, made by the buffalo. He nearly went straight down a craggy precipice of ninety feet. He saved himself with his espontoon and just barely managed to reach a place where he could stand “with tolerable safety.”

Before he could catch his breath, he heard Private Windsor call out, “God, God, Captain, what shall I do?”

Lewis turned and saw Windsor lying prostrate on his belly, with his right hand, arm, and leg over the precipice Lewis had just passed, holding on as best he could with his left arm and foot.

Windsor’s fear was all but overwhelming him. His dangerous situation frightened Lewis considerably, “for I expected every instant to see him loose his strength and slip off.” But, although alarmed, and still shaky from his own hairbreadth escape, Lewis managed to speak calmly.

He assured Windsor he was in no danger, then told him to take the knife out of his belt with his right hand and dig a hole with it in the face of the bluff to receive his right foot.

Windsor did as instructed, and with his foot in the hole was able to raise himself to his knees. Lewis told him to take off his moccasins (the wet leather was more slippery than bare feet) and crawl forward on his hands and knees, taking care to hold the knife in one hand and his rifle in the other. “This he happily effected and escaped.”

Their adrenaline used up, Lewis and Windsor joined the party to proceed. The plains were too slippery and too much intersected with ravines, so “we therefore continued our rout down the river sometimes in the mud and water of the bottom lands, at others in the river to our breasts and when the water became so deep that we could not wade we cut footsteps in the face of the steep bluffs with our knives and proceeded.” They shot six deer, and after making camp at dark ate their first food of the day.

“I now laid myself down on some willow boughs to a comfortable nights rest, and felt indeed as if I was fully repaid for the toil and pain of the day, so much will a good shelter, a dry bed, and comfortable supper revive the sperits of the waryed, wet and hungry traveler.”

His spirits may have been revived, but his worries remained. “The whole of my party to a man . . . were fully peswaided that this river was the Missouri.” Lewis, however, was so certain it was not the Missouri that he named it Maria’s River, after his cousin Maria Wood. “It is true that the hue of the waters of this turbulent and troubled stream but illy comport with the pure celestial virtues and amiable qualifications of that lovely fair one,” he admitted, “but on the other hand it is a noble river . . . which passes through a rich fertile and one of the most beautifully picteresque countries that I ever beheld.”

When the sun broke out around 10:00 a.m., the “innumerable litle birds” that inhabited the cottonwoods along the riverbanks “sung most inchantingly; I observed among them the brown thrush, Robbin, turtle dove, linnit goald-finch, the large and small blackbird, wren and several other birds of less note.”

At 5:00 p.m., “much fatiegued,” he arrived at camp at the junction of the Missouri and Maria’s Rivers. Clark was relieved to see him come in, for he was two days later than expected. The captains conferred, studied the maps they had with them, especially the Arrowsmith 1796 map, and agreed that the south fork was the true Missouri.

The next morning, June 9, Lewis attempted to convince the men of the expedition that the south fork was the Missouri, without success. To a man they were “firm in the beleif that the N. Fork was the Missouri and that which we ought to take.” Private Cruzatte, “who had been an old Missouri navigator and who from his integrity knowledge and skill as a waterman had acquired the confidence of every individual of the party declared it as his opinion that the N. fork was the true genuine Missouri and could be no other.”

Despite Cruzatte’s certainty, the captains would not change their minds, and so informed the men. In a magnificent tribute to the captains’ leadership qualities, “they said very cheerfully that they were ready to follow us any wher we thought proper to direct but that they still thought that the other was the river.”

Lewis and Clark were not taking a vote, but, “finding them so determined in this beleif, and wishing that if we were in an error to be able to detect it and rectify it as soon as possible it was agreed between Capt. C. and myself that one of us should set out with a small party by land up the South fork and continue our rout up it untill we found the falls or reached the snowy Mountains . . . which should . . . determine this question prety accurately.”

Lewis rated Clark the better waterman and decided he should oversee the armada’s progress up the river, while Lewis undertook the land expedition. Besides, Lewis liked to hike—and it may be that he wanted to be the first white man to see the Great Falls.

The captains determined to leave the red pirogue hidden and secured on an island at the mouth of Marias River. Lewis put his brand on several trees in the area.IV The captains also decided to leave much of the heavy baggage in a cache—Cruzatte showed them how to make one. The purpose was to lighten the load, to have a supply depot available on the return journey (a strong indication that they intended to return overland and did not expect to meet a ship at the mouth of the Columbia River), and to provide seven more paddlers for the remaining pirogue and the canoes.

They buried the blacksmith’s bellows and tools, beaver pelts, bear skins, some axes, an auger, some files, two kegs of parched corn, two kegs of pork, a keg of salt, some chisels, some tin cups, two rifles, and the beaver traps. They also buried twenty-four pounds of powder in lead kegs in two separate caches. To leave so much buried in the ground indicated either that the expedition had been grossly overloaded up to this point, or that it was setting off to conquer the Rocky Mountains and whatever lay beyond with inadequate supplies.

In choosing the south fork, the captains had made their most critical decision yet. It was not quite irrevocable, but, considering the lateness of the season, it was almost so.V Not one noncom, not one enlisted man, not Drouillard, presumably not York or Charbonneau or Sacagawea agreed with the decision. Yet such was the spirit of the Corps of Discovery that Lewis could conclude his June 9 journal entry, “In the evening Cruzatte gave us some music on the violin and the men passed the evening in dancing singing &c and were extreemly cheerfull.”

The next day was spent in preparing the caches and making the deposits. Lewis saw and wrote the first description of the white-rumped shrike. He selected Drouillard and Privates Silas Goodrich, George Gibson, and Joseph Field to accompany him on his overland search for the Great Falls. Clark would come on with the remainder of the party in the white pirogue and six canoes.

•

During the night of June 10–11, Lewis suffered an attack of dysentery. He took some “salts,” not otherwise described, for the malady. In the morning, he felt a bit better, but weak. Nevertheless, at 8:00 a.m., “I swung my pack and set forward with my little party.” He was certain that he would discover the Great Falls. Drouillard, Goodrich, Gibson, and Field were sure he would not. They had covered some nine miles when they shot four elk, which they butchered and hung beside the river, for Clark and the party to use. Lewis directed that a feast of the marrowbones be made, but before it was ready “I was taken with such violent pain in the intestens that I was unable to partake.” The pain increased, accompanied by a high fever. It got so bad Lewis could not proceed.

Having brought no medicines with him, he decided to experiment with some simples—exactly what his mother would have done and had taught him to do. He had the men gather some of the small twigs of the choke cherry, stripped them of their leaves, cut them into pieces of two inches, boiled them in water until “a strong black decoction of an astringent bitter tast was produced,” and took a pint of it at sunset. An hour later, he forced down another pint, and within a half-hour “I was entirely releived from pain and in fact every symptom of the disorder forsook me; my fever abated, a gentle perspiration was produced and I had a comfortable and refreshing nights rest.”

At sunrise, 4:30 a.m., Lewis rose feeling much revived. He took another pint of the choke-cherry decoction and set out. It was a glorious day. Despite his illness of the previous day, he made twenty-seven miles. The small party killed two bear. Lewis climbed to a height of land, from which

we had a most beatifull and picturesk view of the Rocky moiuntains which wer perfectly covered with Snow. . . . they appear to be formed of several ranges each succeeding range rising higher than the preceding one untill the most distant appear to loose their snowey tops in the clouds; this was an august spectacle and still rendered more formidable by the recollection that we had them to pass. . . .

This evening I ate very heartily and after pening the transactions of the day amused myself catching those white fish [the sauger, unknown to science; another unknown species, caught by Goodrich on this stretch of the river, was the goldeye]. . . . I caught upwards of a douzen in a few minutes.”

June 13 was an even better day. Lewis climbed to another height in the plains, where “I overlooked a most beatifull and level plain of great extent or at least 50 or sixty miles; in this there were infinitely more buffaloe than I had ever before witnessed at a view.” He struck out for the river, with the men out to each side with orders to kill some meat and join him at the river for dinner.

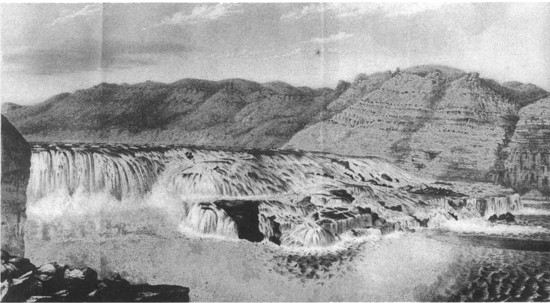

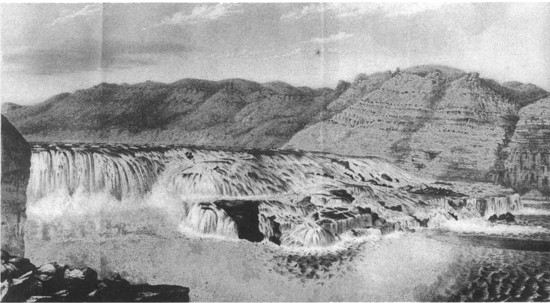

“I had proceded on this course about two miles . . . whin my ears were saluted with the agreeable sound of a fall of water and advancing a little further I saw the spray arrise above the plain like a collumn of smoke. . . . [It] soon began to make a roaring too tremendious to be mistaken for any cause short of the great falls of the Missouri.” He arrived at the river about noon and hurried down the two-hundred-foot bluff to a point on top of some rocks on an island, opposite the center of the falls, “to gaze on this sublimely grand specticle . . . the grandest sight I ever beheld.”

A. E. Mathews, Great Falls of the Missouri (1867). (Montana Historical Society)

He all but tripped over himself in attempting to describe the falls. After seven hundred words, he was “so much disgusted” with his “imperfect” description that he almost tore up the pages, “but then reflected that I could not perhaps succeed better than pening the first impressions of the mind.” He wanted to “give to the enlightened world some just idea of this truly magnifficent and sublimely grand object, which has from the commencement of time been concealed from the view of civilized man,” a nice indication of just how seriously he took his role of being the first white man to see such sights and the resulting responsibility to describe them to “the enlighted world.” He regretted that he did not have the “pencil of Salvator Rosa or the pen of Thompson.” (Rosa was a seventeenth-century Italian landscape painter; James Thomson was an eighteenth-century Scottish poet.)

He did not neglect to describe his own feelings—the sight filled him with “pleasure and astonishment”—but he did not indicate that the sight gave him the satisfaction of having been right about the true Missouri River. Still, he must have felt it, not only as vindication of his thought process but even more because he now knew for certain that Clark and the expedition were coming the right way.

Drouillard and the privates met him on his island camp with plenty of prime buffalo meat. Goodrich caught some trout, unknown to science, described by Lewis, delicious to eat—they were cutthroats.

Sitting at his camp at the foot of the falls, Lewis concluded his entry for June 13: “My fare is really sumptuous this evening; buffaloe’s humps, tongues and marrowbones, fine trout parched meal pepper and salt, and a good appetite; the last is not considered the least of the luxuries.” A fine ending to a memorable day.

In the morning, Lewis sent Private Field with a letter to Clark, telling him of the discovery of the falls. He set the remainder of his party to work drying meat, then took his gun and espontoon and went for a walk. He thought he would go a few miles upstream to see where the rapids terminated. It couldn’t be far—the Hidatsas had said the portage took half a day.

For the first five miles, however, it was one continuous rapid. Lewis came around a bend and to his surprise saw a second falls, this one of some nineteen feet, or about half as high as the first falls. He named this one Crooked Falls. He pushed on. “Hearing a tremendious roaring above me I continued my rout . . . and was again presented by one of the most beatifull objects in nature, a cascade of about fifty feet perpendicular streching at right angles across the river . . . a quarter-mile. . . . I now thought that if a skillfull painter had been asked to make a beautifull cascade that he would most probably have presented the precise immage of this one.”

Inevitably, he compared this one with yesterday’s discovery. “At length I determined between these two great rivals for glory that this was pleasingly beautifull, while the other was sublimely grand.”

Then there was another fall, of fourteen feet, then another of twenty-six feet. Altogether, five separate falls made up the Great Falls of the Missouri. The Hidatsas had never mentioned more than one. It suddenly looked like a much longer and more difficult portage than Lewis had anticipated.

Finally, there was an end to the twelve-mile stretch of falls and rapids. Lewis arrived at a point where the Missouri “lies a smoth even and unruffled sheet of water of nearly a mile in width bearing on it’s watry bosome vast flocks of geese which feed at pleasure in the delightfull pasture on either border.”

He was quite beside himself with joy. He wrote of “feasting my eyes on this ravishing prospect and resting myself a few minutes.” Then he decided to proceed as far as the river he had seen entering the Missouri from the northwest, a river the Hidatsas had mentioned and which they called Medicine River.

His walk took him past the biggest buffalo herd he ever saw—and therefore quite likely the biggest buffalo herd any white man ever saw. He thought he would kill a buffalo, then pick up the meat he needed for his dinner on his way back to camp from Medicine River. He shot a fat buffalo through the lungs, and watched as the blood spurted from its mouth and nostrils. Distracted by the sight, he forgot to reload his rifle.

At that moment, he became the hunted. Behind him, a grizzly had crept to within twenty steps of Lewis. Seeing the bear, Lewis brought up his rifle, but instantly realized she wasn’t loaded, and further realized that he had not nearly enough time to reload before the bear—now briskly advancing—reached him.

Instinctively, he searched the terrain. Not a tree within three hundred yards. The riverbank was not more than three feet above the level of the water. In short, no place to hide in order to gain enough time to reload.

He started to walk faster. The bear pitched at him, “open mouthed and full speed, I ran about 80 yards and found he gained on me fast.”

Lewis ran into the river, thinking that if he could get to waist-deep water the bear would be obliged to swim. Lewis hoped he could then defend himself with his espontoon.

He got to the waist-deep water, turned on the bear, “and presented the point of my espontoon.”

The bear took one look and “sudonly wheeled about as if frightened, declined the combat on such unequal ground, and retreated with quite as great precipiation as he had just pursued me.”

Lewis learned a lesson: as soon as “I returned to the shore I charged my gun, which I had still retained in my hand throughout this curious adventure. . . . My gun reloaded I felt confidence once more in my strength . . . determined never again to suffer my peice to be longer empty than the time she necessarily required to charge her.”

He got to, examined, and described Medicine River. By the time he was finished, it was 6:30 p.m. About three hours of daylight left, and twelve miles to hike back to camp.

He started down the level bottom of Medicine River. Just short of its junction with the Missouri, he spotted what he at first thought was a wolf; on getting to within sixty yards of it, he decided it was catlike. (It was probably a wolverine.) Lewis used his espontoon as a rest, took careful aim, and fired at it; the animal disappered into its burrow. On examination, the tracks indicated the animal was some kind of tiger cat. Lewis saw no blood; apparently he had missed, which mortified him and bothered him not a little, since he absolutely depended on that rifle for his life (which was why he had had it with him, unloaded, in the river as the bear advanced on him; if he went down, it would be with his rifle in hand), and he was sure he had taken careful aim and that his rifle shot true.

He had not taken three hundred more steps when three buffalo bulls, feeding with a herd about half a mile away, separated from the others and ran full-speed at Lewis. He thought to give them some amusement at least and changed his direction to meet them head-on. At one hundred yards, they stopped, took a good look at Lewis, turned, and retreated as fast as they had come on.

“It now seemed to me that all the beasts of the neighbourhood had made a league to distroy me, or that some fortune was disposed to amuse herself at my expence,” he wrote.

He returned to the carcass of the buffalo he had shot in the morning, where he had thought he might camp, but decided to go all the way to base camp at the foot of the first falls: he “did not think it prudent to remain all night at this place which really from the succession of curious adventures wore the impression on my mind of inchantment.”

At times, walking over the plains as full darkness came on, he thought it was all a dream. But then he would step on a prickly pear.

In the morning, June 15, he spent hours writing in his journal (his entry covering his June 14 adventures is some twenty-four hundred words long; at twenty words a minute of stream-of-consciousness writing, with no pause for reflection, it would have taken him two hours minimum). Then “I amused myself in fishing, and sleeping away the fortiegues of yesterday.”

The curious adventures that marked the week he discovered there were five great falls, not one, were not finished. When Lewis awoke from his nap, “I found a large rattlesnake coiled on the leaning trunk of a tree under the shade of which I had been lying at the distance of about ten feet from him.” He killed the snake—he does not bother to tell how—and examined it (176 scuta on the abdomen and 17 on the tail).

Private Field returned, to report that Clark and the main party had stopped at the foot of a rapid about five miles below. Clark thought he had gone about as far upstream as possible, and that the portage should therefore begin from that place. Lewis needed to examine the ground. He had already decided there were too many ravines on the north bank, and that, because the river bent toward the southwest, a portage on the south side would be shorter.

Where and how he did not know. Or how long it would take. But it was obviously going to be a much greater task than he had anticipated, and far more time-consuming.

In a week, the days would start getting shorter. And always in the back of his mind, even as he wrestled with his immediate problems, were those tremendous mountains looming to the west, standing between him and his goal—mountains that he could only just see, but which he already realized were much greater, higher, deeper than anything he had seen in the Blue Ridge, or anywhere else. For a man who could never expect to travel more than twenty-five miles in one day, he was in a tremendous hurry.

He was eager to vault his energy over those mountains before winter set in, but he had to deal with the reality of a more-than-sixteen-mile portage over rough terrain, do it patiently, and use the time in as positive a way as possible.

I. The explanation was simple, although it did not occur to Lewis or Clark, probably because their orientation was so completely centered on the river. When the Hidatsas raided to the west, they went on horseback. They could easily cut the big bends in the Missouri by riding overland. Up on the plains, they saved not only miles but the very rough country of the breaks and White Cliffs. Following that route, they would strike the Missouri again at or south of Fort Benton, and thus never see the river coming in from the northwest that so puzzled Lewis.

II. Sacagawea was of no help. She had not been on this part of the river.

III. A modern floater’s guide to Montana states that the gravel roads in the area of the river are like “impassable grease” after a rain. Moulton, in his note to the June 7, 1805, entry, calls this clay a “gumbo,” and writes, “Only a small amount of moisture is needed to make it extremely slippery.”

IV. The branding iron bore the legend “U.S. Capt. M. Lewis.” It is now in the Oregon Historical Society Museum, one of the few surviving authenticated articles associated with the expedition. It was found near Hood River, Oregon, in 1892, 1893, or 1894. See Moulton’s note to the entry of June 10, 1805.

V. Had the expedition gone up Marias River, at about one hundred miles it would have reached a fork, the junction of the Two Medicine and the Cut Bank Rivers. Had the party taken the left-hand fork, it would have arrived at Glacier National Park in the vicinity of present East Glacier. It would have gone over the Contintenal Divide at Marias Pass—the route that the Northern Pacific Railroad later used, and still uses today. That would have put the expedition in the Columbia River drainage—down the Middle Fork of the Flathead River to the Flathead, then south until eventually making a junction with the Clark’s Fork, running north to the Columbia. As the crow flies, this would have been the shortest route, but it would have taken the party through an incredible jumble of mountains and whitewater, without horses. At the least, the odds would have been against the men and their captains.