How to Prepare for Treatment

STARTING TREATMENT CAN BE UNNERVING because you don’t know what to expect and because this is the part where you become a patient being treated for cancer. You may have had surgery already and everything may feel very surreal. This time is one of the toughest because you don’t know how your body is going to respond to treatment. You don’t yet know how to trust this new body, but you will. You will become a competent, capable cancer patient. I wish you didn’t have to, but you will.

In this chapter, I’m going to talk you through everything you need to know to prepare for radiation or chemotherapy. First, I’ll explain the basics of radiation therapy and how to prepare for it. Then, I’ll explain what chemotherapy is and how different classes of chemotherapy work. I’ll describe a typical day in the infusion unit, the facility inside the hospital or clinic where chemotherapy is provided. I’ll also tell you what you need to know about side effects, and how you can adjust your schedule for chemotherapy to better fit into your life.

This is one of the mainstays of cancer treatment, because radiation kills cancer cells by damaging their DNA. If the cells have enough radiation damage, then they will die when they go to divide. Many cancer cells don’t divide for four to eight weeks, which is why it often takes two months to see the optimum effect of radiation therapy.

People sometimes ask why we can’t apply radiation therapy to the whole body if it works this well to kill cancer cells. The answer is that radiation damages normal tissues in the same way that it damages cancer cells. So doctors think of radiation as a local therapy that should be directed at tumors alone. You can think of it the same way you would think about surgery, except without the incision and the pain.

There are two types of radiation therapy: internal and external. For internal radiation therapy—also called brachytherapy—a radiation oncologist places radioactive beads inside the body next to a tumor. Brachytherapy is sometimes used for patients with local tumors in the prostate, breast, and cervix, but there are limited applications for this kind of therapy. The most common form of radiation therapy is external beam radiation. A machine called a linear accelerator produces a beam of radiation therapy that goes into and through your body.

Why Do I Need Radiation?

There are several reasons doctors recommend radiation instead of surgery or in addition to chemotherapy. Some people are not good candidates for surgery, while others have a type of tumor that might be equally treatable with radiation or surgery. For example, men with prostate cancer often debate the merits of surgical removal of the tumor versus primary radiation therapy to treat a localized prostate tumor. Sometimes elderly patients with lung cancer are treated with primary radiation therapy because thoracic surgery to remove a lung cancer is deemed too dangerous.

Doctors also recommend radiation therapy in addition to surgery when there is a strong suspicion that microscopic cancer cells may remain around the site after the tumor has been removed. This is called adjuvant radiation therapy. Even if a surgeon has cut a wide swath around the tumor, patients can still be at risk of another tumor developing from those cells that were left behind. If the tumor was large or if there were a number of lymph nodes that showed metastases, that is, the spread of cancer cells to another location, doctors may suspect that there are cancer cells in the tissues surrounding the tumor that weren’t removed. Some cancers are like jellyfish in that they grow tentacles outward from the central tumor and these can’t be seen on scans. If there is a high chance that some cells remain after surgery, your doctor may want to use radiation on that area to have a better chance of killing those cells. If you get radiation prior to surgery to help shrink the tumor, this is called neoadjuvant radiation therapy. Adjuvant and neoadjuvant radiation should be used only when evidence from clinical trials supports it.

Radiation can also be used to reduce symptoms from metastatic cancer. In fact, it’s a wonderful way to reduce or even eliminate pain from metastatic sites, including bone metastases. It can also stop cancers from bleeding or growing into vital structures such as the spinal cord.

The Planning Session

Everyone who gets radiation therapy undergoes a planning session, often called a simulation, or “sim.” This planning session can often take an hour to complete. The radiation oncologist and radiation physicist will position your body so that multiple beams of radiation will cross the area of the tumor. By using multiple beams of radiation, the radiation oncologist can concentrate the highest dose around the cancer and limit the amount of radiation therapy normal tissues see.

When they have figured out the appropriate position for your body, one of them will place a small tattoo on the skin as a reference point. This ensures that the radiation therapist can position you correctly for each session of radiation. The tattoo is usually a small blue dot the size of a pen mark. Correct positioning is critical, and that’s why you will receive a small tattoo. If you have tumors in the brain, head, and neck, you might need to be fitted with a mask that will be used with each radiation treatment to make sure that the beam is in exactly the right position.

The radiation oncology team will discuss all of this with you and take you through it step by step. It can sound daunting, but just like with chemotherapy, once you learn the ropes and your team, it will all feel easier.

How Much Radiation Will I Need?

You may be scheduled to receive either a long course or a short course of radiation. In a long course, smaller amounts of radiation are delivered every day over an extended time, perhaps four to six weeks. In short course radiation therapy, larger doses of radiation are delivered every day over an abbreviated period, such as one week. There are pros and cons to the different schedules of radiation for each tumor type.

The dose of radiation that any patient receives is measured in Grays, named after Henry Louis Gray, one of the pioneers in X-ray technology. A Gray is often abbreviated Gy. Each Gy is equivalent to one joule of energy absorbed per kilogram of tissue. The total amount of Gys that are required to kill a tumor is dependent on the individual tumor, but many tumors require 40 to 70 Gy to be killed. By comparison, a CT scan has 16 mGy, or 0.16 Gy. The amount of radiation delivered with each dose is called a fraction, and this is also measured in Gy.

You will typically need to arrive for radiation at the same time each day, and you will usually have the same radiation therapist to position you on the table and direct the radiation based on the location of your small tattoo. The radiation itself will be over in just a few minutes, but the entire visit to the radiation oncology department will generally take thirty to forty-five minutes. Like everything else, you will get used to the routine, and the staff will be able to get you in and out pretty quickly. I have had many patients tell me that they become friendly with the other patients getting radiation at the same time because you do see each other every day for up to several weeks. You become radiation buddies. When you complete a course of radiation at MGH, you get to ring a bell in the waiting room if you want. It becomes a celebratory moment to mark completion of the course.

Side Effects of Radiation

There are both short- and long-term side effects to radiation.

Fatigue. This is the most common immediate side effect of radiation. I tell my patients to expect to be exhausted beginning about two weeks after the radiation starts and lasting until two weeks after it ends. People who never needed an afternoon nap before will find themselves napping regularly. This will subside over the course of about a month, but I encourage people to think about how they will manage this fatigue so they are prepared.

Inflammation. Although the treatment itself is painless, radiation does cause some short-term swelling in soft tissues. This swelling can cause pain, but it is generally temporary. The specific side effects you may experience will depend on the location of the tumor and the direction of the radiation. If a tumor is close to the skin, you may develop what looks like a sunburn in that area. If radiation hits the gastrointestinal tract, you may develop nausea or diarrhea.

Scarring. The normal tissues in the path of radiation beams can sustain long-term damage. For women who receive radiation to the underarm for breast cancer, this scarring can cause the affected arm to swell. If radiation has hit the digestive tract, you can get scarring that causes obstructions there. Occasionally, vital organs can be scarred, including the heart and kidneys, and this can lead to long-term damage. Radiation oncologists do everything they can to avoid vital organs, but sometimes the location of the tumor doesn’t allow for this.

Bone marrow suppression. Radiation can damage the stem cells in your bone marrow, which can impair the production of blood cells in your body. You may have low blood counts after getting radiation to certain parts of your bone marrow. Usually, your body can bounce back quickly.

Pneumonitis. Sometimes patients can develop pneumonitis, or inflammation of the lung, if a portion of a lung has been radiated. This can sometimes be serious, and if you experience a cough or shortness of breath, you should call your oncologist. These symptoms can occur several weeks after the radiation is done. Sometimes we need to treat pneumonitis with steroids.

Cancer. The risk of developing a new radiation-induced cancer in the area that was radiated is about 1 percent over the course of the next twenty years. Still, this is a serious consideration that must be weighed against the beneficial effects of radiation for treating cancer. Tissues at high risk of developing cancer are those in young people that are still growing. That’s why doctors do everything they can to limit the amount of radiation to hit normal tissues in children and adolescents.

What Is Proton Beam Radiation?

Conventional radiation uses photons or X-rays that enter and exit the body. With protons, by contrast, there is no exit dose of radiation beyond the tumor. Instead, a narrow concentration of radiation is delivered to the tumor itself. In essence, radiation oncologists can “paint” the radiation around the tumor more precisely and limit the normal tissues receiving radiation.

Proton beam therapy is not more effective at killing the cancer. It’s merely more effective at limiting the long-term side effects of radiation. In some tumors, such as brain tumors in children, the advantages are obvious. But the advantages are less obvious in most adult solid tumors, and studies are under way comparing photons to protons. Generally, proton beam therapy is not considered standard care, and we do not offer it to solid tumor patients unless they are enrolled in a clinical trial.

What Is Chemotherapy?

Chemotherapy in its broadest sense is chemical therapy. Really, all of medicine is the use of chemicals to treat people. But, chemotherapy has come to mean any anticancer medication. Chemotherapy can be subdivided into four major categories: traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy. Each of these categories carries different side effects that can be easy or difficult to tolerate, and each can be administered in several ways. They can be given intravenously (through the vein), orally (by mouth), or subcutaneously (under the skin).

Traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy kills cancer cells usually by damaging their DNA in some way. This is the category of chemotherapy with which most people are familiar. It can cause nausea, hair loss, low blood counts, and all the other traditional side effects associated with chemotherapy. It can be given by an intravenous infusion or orally. Just because a drug can be given orally doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s better tolerated or safer for the patient.

Hormonal therapy kills cancer cells that are dependent on being fed by hormones in your body, specifically estrogen and testosterone. Many breast cancers respond remarkably well to antiestrogens. The side effects are often quite manageable when compared with traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy, but these treatments can cause problems such as early menopause, osteoporosis, cataracts, and other long-term complications caused by low estrogen. In much the same way, prostate cancer feeds off testosterone. Prostate cancers will stop in their tracks and often die as soon as you remove testosterone from the system. We can do this by surgically removing the testicles or by administering antitestosterone medications. Removing testosterone, however, can produce many long-term side effects such as diminished energy level, weight gain, increased risks of heart attacks, osteoporosis, diminished libido, and erectile dysfunction.

Of course, these side effects can be very disruptive. Sometimes patients feel that their oncologists don’t pay enough attention to their complaints about these deeply personal bodily changes. Oncologists can sometimes seem to dismiss these upheavals because they have patients dealing with life-threatening side effects from other therapies. I hope this isn’t the case for you, because your oncologist should be taking these side effects seriously. One of the major contributions we have made as palliative care clinicians is to help the oncologists recognize the impact hormonal agents can have on the overall well-being of patients.

Immunotherapy treatments are chemicals or proteins that are designed to augment or activate immune cells to fight the cancer. Typically, these regimens have none of the usual side effects associated with traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy that you receive in the infusion unit. So we often won’t use antinausea medicines, and we are not worried about hair loss or low blood counts. But they can activate the immune system to such a degree that it can accidentally start attacking normal tissues and organs.

For instance, Jim is a fifty-eight-year-old man with melanoma who was prescribed immunotherapy. Every three weeks he was scheduled to come to the infusion unit for a one-hour visit in which the nurse would give him the drug intravenously. He felt fine at the time of his first infusion and for the next couple of days, but during the second week after receiving the drug, he started to have severe diarrhea, occasionally as often as seven or eight times per day. Other than the diarrhea, he felt fine. It turns out that the immunotherapy that Jim was receiving was causing his T cells—immune cells—to attack his colon. When he had a colonoscopy, it looked just like ulcerative colitis, an autoimmune disease where a patient’s immune cells attack his or her colon. In fact, many of the new immunotherapy medications are causing autoimmune diseases as their main form of toxicity. Thankfully, most go away when you stop the medication.

Targeted therapy refers to medications that target a specific protein pathway that the cancer cells are using to survive. For this type of treatment, we rely on the molecular pathologist to study the DNA of the cancer cell and tell us whether a mutation that the tumor has is creating too much or too little of a specific protein, which may be allowing the cells to grow out of control. For certain mutations, there are treatments that shut down the protein pathway and allow the cells to die naturally. In chapter 2, Dave describes the importance of determining the genetic defects of the cancer, and targeted therapy is directed at these defects.

These medications can be given intravenously, usually when they are antibodies against a specific protein, or orally, often called targeted therapies. Your oncologist may refer to them as tyrosine kinase inhibitors. These tyrosine kinase inhibitors have very different kinds of side effects compared with standard chemotherapy. You probably won’t experience nausea or low blood counts. But you may experience reactions such as rashes and sometimes specific organ toxicities. For instance, Sarah is a forty-nine-year-old woman who is receiving a targeted therapy against a protein called HER2 for her breast cancer. After about six months on the therapy, she started to get short of breath when she was climbing the stairs. It turns out that the medication was affecting her heart muscle. When her oncologist stopped the drug, her heart muscle returned to normal, and she could walk without a problem. There are times when a targeted therapy is doing a great job of controlling the cancer, and yet it causes such severe side effects that it needs to be stopped.

Targeted therapies have been one of the major advances in the past ten years of oncology, and their use has dramatically enhanced our understanding of how cancers become resistant to different medications. If you are fortunate to have the type of cancer that responds to a targeted therapy, you should know that the cancer will likely become resistant to this treatment at some point. It’s similar to the way in which chronic infections eventually become resistant to a certain antibiotic. Oncologists are now using repeat biopsies of cancer cells that have become resistant to a targeted treatment to see whether another targeted therapy will be effective.

Sometimes, oncologists use a combination of several types of drugs to treat cancer. It can often get confusing for patients and their families, but asking about which class of drugs your treatment falls into will help you keep track of the kinds of side effects you can expect. It will also help you better understand what your team is trying to accomplish.

Getting Ready for Chemotherapy

There are several questions you will want to ask your doctor about chemotherapy to help you get oriented before you start. Even if you have already started treatment, these questions will spark important conversations about treatment and how you can better prepare yourself:

What Is a Cycle of Chemotherapy?

Chemotherapy is like many medical treatments in that you will need several of them to get good results, and a standard grouping of these treatments is called a cycle. Oncologists think solely in terms of cycles of chemotherapy. Every type of chemotherapy has a different measurement that constitutes a cycle. For regimens that are given weekly, a cycle usually refers to four weeks of treatment. For regimens that are given every other week or every three weeks, each treatment will usually be considered its own cycle. For oral regimens, oncologists usually label a cycle as a month of therapy, because most of these regimens have a set number of days that you will be taking the drug. Sometimes you get these medications continuously, and sometimes these medications are given for a set number of weeks followed by a set number of weeks off of the medication. These are rough guidelines, and you should always ask your oncologist what he or she considers a cycle for your specific chemotherapy regimen.

So your doctor should be able to tell you how many treatments you will need to complete a cycle and how many cycles of treatment you will need to complete before tests will show how well the treatment is working. Your doctor is also going to be monitoring how your body reacts to chemotherapy at different points in a cycle, so that he or she can adjust the dosage for the next cycle if you experience toxicity.

All chemotherapy regimens cause some side effects, but your doctor is going to be checking to see whether you are developing what’s called toxicity. It sounds serious, but really it means any side effect caused by the medication.

Some toxicities are so mild that we hardly pay any attention to them. For instance, some drugs will cause mouth sores that last for a day or two. Other toxicities can be life threatening, and we have to follow you closely. Luckily, you don’t have to worry about what these kinds of toxicities are because we are often following them by checking your labs. Certain toxicities can happen at the beginning, middle, or end of a cycle, and your doctor will be monitoring your health to check for them. If your doctor is concerned about toxicity affecting your health, he or she may decide to give you a lower dose of the chemotherapy during the next cycle. Some patients try to argue with oncologists who want to reduce the dosage. You should know that lowering the dose of chemotherapy won’t necessarily reduce its efficacy. Instead, the oncologist is trying to make sure that your body can tolerate the treatment.

What Is an Infusion Like?

Intravenous chemotherapies are referred to as infusions. The length of the actual infusion will be different for each regimen of chemotherapy. Some are relatively short, an hour, and some can take up to eight hours, so it’s good to ask how long the infusion will take for your type of chemotherapy. A few regimens require a two-day infusion, but that doesn’t mean you will be in the hospital for two days. Instead, the infusion will be started via IV in the infusion unit, and then you will go home with a portable pump and come back two days later to have it disconnected.

While in the infusion unit, you will be attended to by nurses who are experts at answering your questions about the process and at making you more comfortable. They can get you blankets and ice chips and help keep you updated on the progress of the infusion. In some hospitals you will have the same infusion nurse throughout your treatment, and he or she will get to know you really well and will be an enormous asset during this time.

In addition to administering the actual infusion, these nurses are carrying out the important function of double-checking the doses of the medications that have been ordered and checking with the pharmacy to see when they will be mixed. Infusion nurses are also communicating with your doctor about how you are doing on any given day. If you are being given extra medications or fluids through your IV to help with side effects, infusion nurses know exactly what these are and why they are being given. So if you have questions about anything, this is the person to ask. Infusion nurses also have a lot of information and tips about how to deal with side effects.

Do I Need a Portacath?

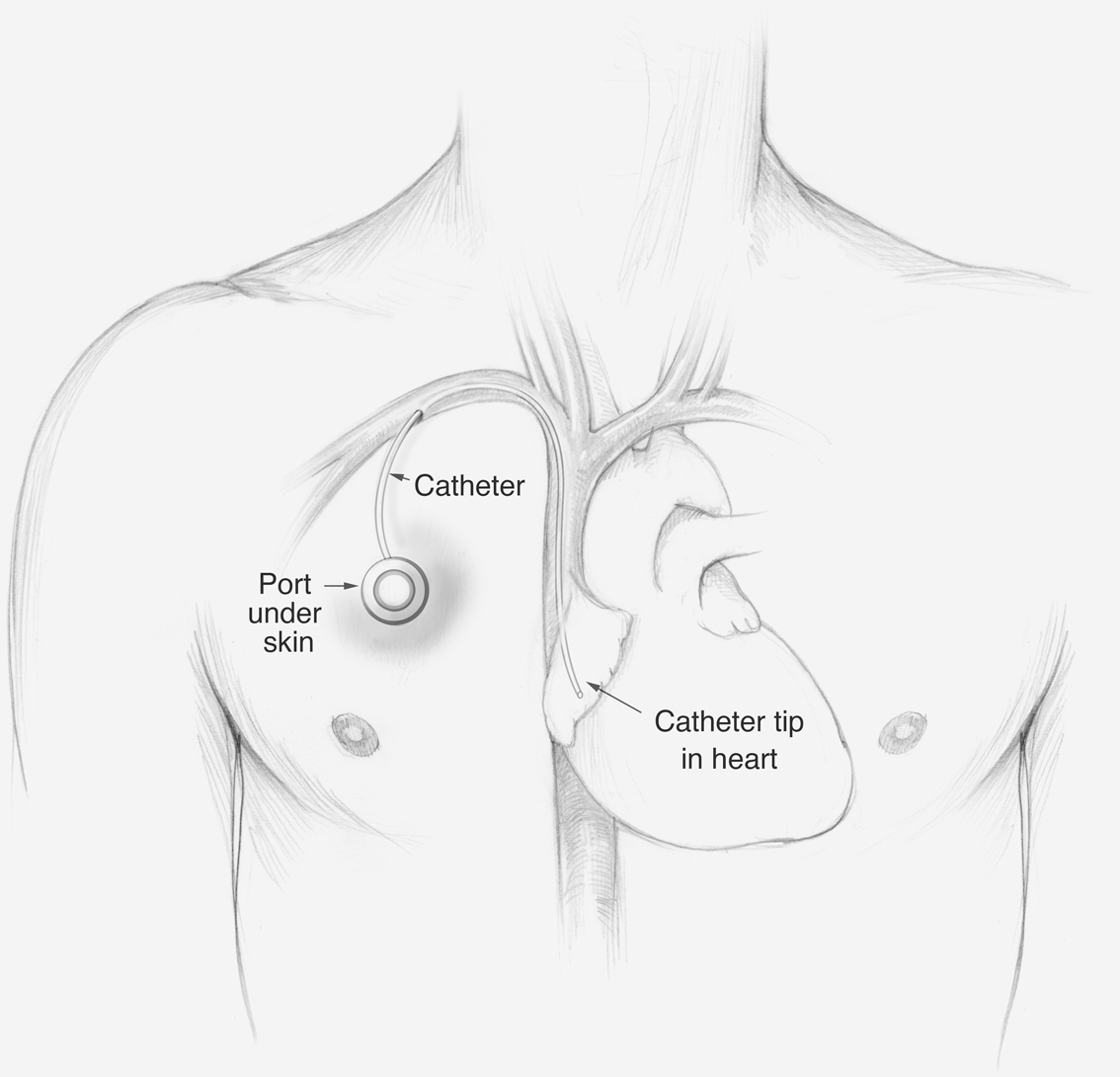

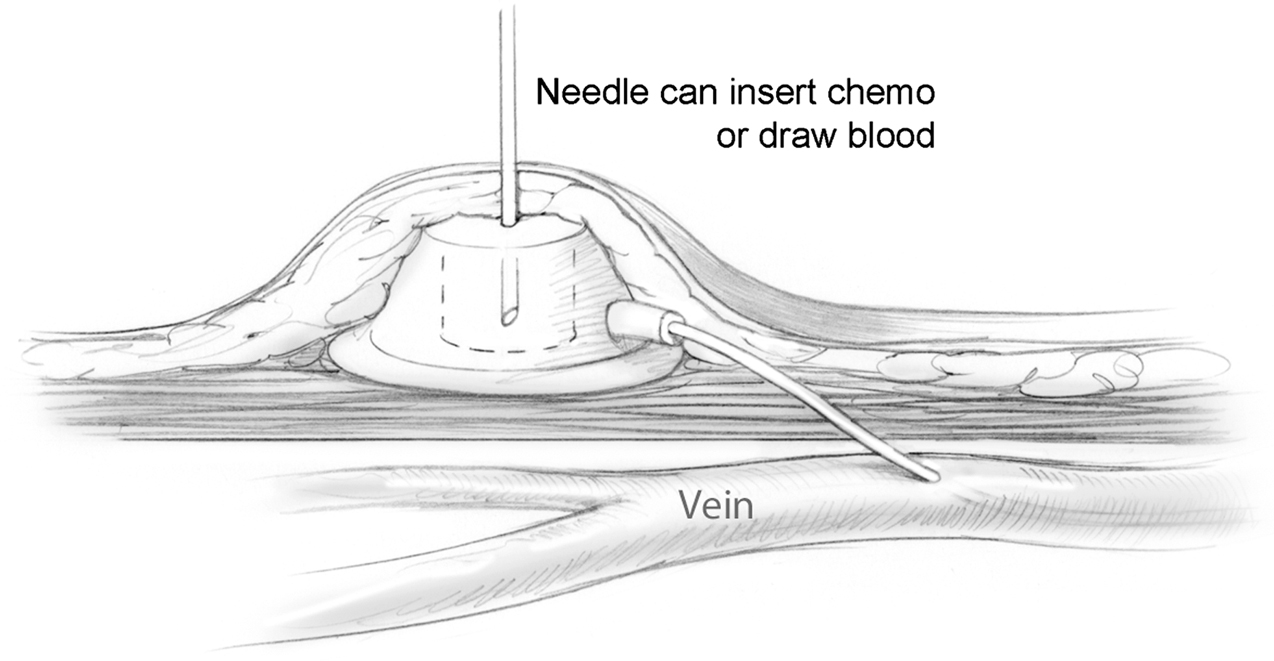

We sometimes recommend that people who are getting intravenous chemotherapy get a portacath, also called a port. These are special venous access devices that are implanted under your skin (figure 5.1). The port is a disk with a chamber that attaches to an intravenous catheter, so that the infusions can be delivered into your bloodstream. This prevents the nurses from having to insert an IV line into your arm with every infusion, and it allows nurses to easily do a blood draw without searching for a vein in the arm. But it’s not merely a convenience for infusion nurses. Many patients hate the constant sticks in the arm that it can take to find a vein for infusions. And after several months of infusions, some of the veins can become scarred and difficult to access.

An interventional radiologist or surgeon at your hospital can insert the port during a procedure that generally takes about forty-five minutes. You will receive local anesthesia to numb your skin along with intravenous medications to lessen any pain and anxiety. When the procedure is finished and the local anesthesia wears off, you will feel some discomfort that should resolve over the course of a day. It’s fine to take acetaminophen or oxycodone for a day or two to ease the discomfort.

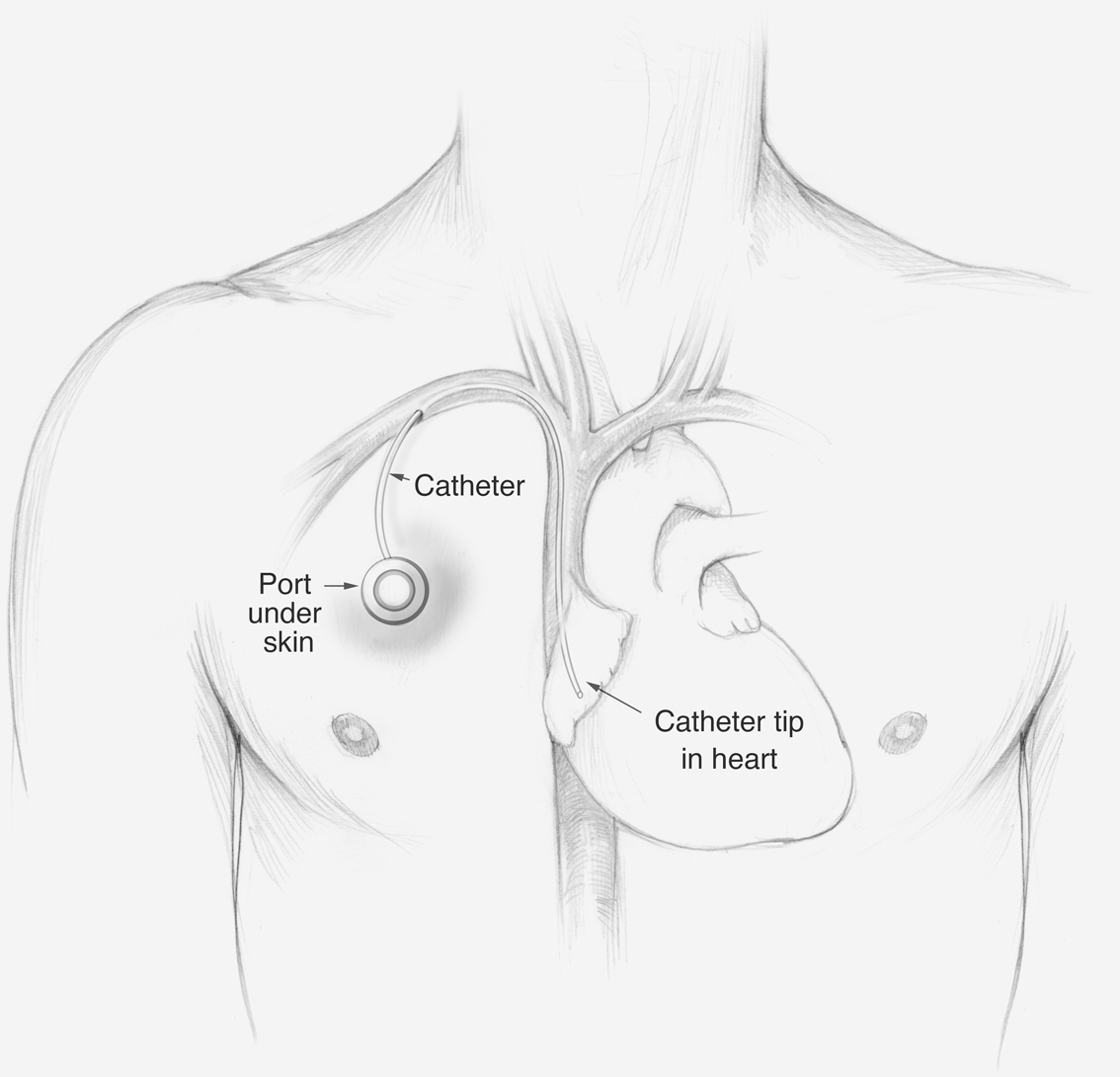

The port will look like a half-dollar just underneath the skin below your collarbone. An infusion nurse can insert a needle into the port to give you intravenous medications or fluids, or to take a blood draw (figure 5.2).

Figure 5.1 Placement of portacath

Some chemotherapy drugs can be given only through a port because they are too toxic to administer through smaller peripheral veins. If you are receiving one of these regimens, your only options are to have a port or to have a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) placed. PICCs are long IV catheters that you can leave in place for weeks at a time, but they are less convenient because you have to leave the IV taped to your arm for the entire time that you have it. By contrast, a port is covered entirely by your skin, so when it’s not being accessed, you can swim and shower without damaging it.

Figure 5.2 Inserting a needle into portacath

There are two major concerns about ports, however. The first is that they can become infected, so anyone who accesses the port has to use sterile technique. Ports can also clot, and they can be a source of blood clots that can travel to the lung. If a port becomes infected or clotted, it almost always has to be removed. Ultimately, you should ask your doctor whether a port is right for you.

What Is a Day of Chemo Like?

While the infusion itself may take only a short time, a typical day in the clinic is likely to be much longer. Like most everything associated with medical treatment, there will be several necessary steps you have to go through along with some waiting around. To get an infusion, all these steps have to happen in order:

Sometimes the lab gets backed up doing blood counts, sometimes your clinician is running late because of an emergency, and sometimes the pharmacy gets overwhelmed with chemotherapy orders. So the infusion may not start exactly at the appointed time. I had a patient, Stan, who was a grade school teacher, and very meticulous. During one of our first appointments, he stood to excuse himself, telling me that he had to hurry to the infusion unit because his appointment was at 10 a.m. exactly. I had to tell him that the nurses on the unit weren’t expecting him exactly at his appointment time. They know that they can’t give an infusion until the blood work comes in, the clinician orders the chemo, and the lab has mixed it. In this case, it’s okay to just relax and go with the process.

I find that patients do best when they plan to spend an entire day in the infusion unit by bringing something to do, a book to read, movies to watch, or a loved one or friend to spend some of the day with them. Then, if things run really smoothly and they are done in a few hours, they consider it a bonus.

There are several things you can do to help speed things along:

Additional Medications

After you get to the infusion unit and your nurse has the chemotherapy mixed for you in hand, you will get different medications to help with the side effects of the chemotherapy. You might get antinausea medications like ondansetron, which are more fully explained in chapter 9. These drugs dramatically reduce the nausea that patients experience from chemotherapy. You might have been instructed to take some steroids the night before the chemotherapy infusion. Taking all these medications as prescribed is crucial to minimize the side effects of the chemotherapy infusion.

Allergic Reactions

Many people have allergies of some kind, and most people know of someone who is allergic to some class of medication. Chemotherapy is no different in that there are some people who have, or develop, an allergic reaction to the chemotherapy drug they are being given. Rest assured that infusion nurses are experts in seeing and treating even mild allergic reactions. This is one of the reasons they will be constantly checking on you to see how you are responding to each infusion.

Most times an allergic reaction is mild, such as a single hive on your arm. It’s rare but possible for certain patients to develop an overwhelming allergic reaction, called anaphylaxis, in which the tongue will begin to tingle and swell and they may start to wheeze or cough. In some people a reaction is preceded by a funny feeling in the head or body, and, in a few of these cases, people have a severe and sudden reaction in which they pass out before they know what’s happening. Know that a capable nurse will be steps away from you at all times during your infusion and that if you do have even a mild reaction, your nurse will stop your infusion immediately and give you medications such as steroids and antihistamines to stop it.

Patients who do have a severe reaction may have to see an allergist to undergo desensitization to the chemotherapy, just as you would undergo desensitization to penicillin if you were allergic and really needed it.

Side Effects

You probably already know that chemotherapy causes some side effects. The classic examples in movies and television are nausea and hair loss, but every regimen is different, and some regimens don’t result in either of these side effects. Some side effects, such as nausea, can be controlled well with medication, while most—including hair loss—are temporary. Side effects such as nausea will change and improve in the days following an infusion, while other side effects may be cumulative over the course of a cycle of treatment.

The best way to prepare is to ask your oncologist what kinds of side effects are common for your regimen. Rather than asking for the entire list of possible side effects, ask for a list of the top three. Ask whether these side effects happen almost always, usually, or only sometimes. Ask how long these side effects are likely to last. You will also want to know whether any of the side effects can be cumulative. Will they likely be worst during the first infusions, or are they likely to be worst during the final infusions of a cycle? Whom do I call when something seems amiss or when I have a question? That last question is extremely important. Some oncologists will have you call an answering service, while others will give you an office number or their direct e-mail address or cell phone.

Knowing the answers to these questions will help you plan the other activities in your life, so that you are doing the things that are important to you when your energy is highest and when you feel most like yourself. Although side effects such as fatigue and nausea or rashes or mouth sores are disruptive and frustrating, there will likely be days during treatment when you feel pretty good. We talk a lot in treatment about planning to cope during those days when you feel crummy, but you also want to plan for those days when you feel strong and able to get out and live your life.

The most common side effects include fatigue, rash, diarrhea, hair loss, and mouth sores.

Fatigue. Most people experience fatigue in two ways. There is the immediate fatigue that a person feels after the infusion of chemotherapy. Some people fall asleep during the infusion. Most patients just hunker down those first couple days until they begin to feel better. The other kind of fatigue is more cumulative. If you are getting chemotherapy for several cycles, you may be more tired at the end of a cycle or at the end of several cycles.

Plan to get out and move around when you feel more energetic. Even going for a short walk will help you stay energized and keep you from becoming deconditioned, which can make you even more tired. We discuss fatigue more in chapter 16.

Rash. This is a common side effect of newer, targeted therapies. It looks sort of like an acne rash. One patient of mine was taking an oral regimen for chemotherapy, and she felt fine after each dose. The problem was that she had a rash on her face and that made her feel as though she didn’t want anyone to see her. She told me that she felt like a fourteen-year-old kid and didn’t want anyone taking pictures of her. We put her on an antibiotic for the rash, which cleared it up enough that she could go out without feeling that she had to explain why she looked so different.

Diarrhea. Certain therapies, including irinotecan, have this unfortunate side effect. The newer, targeted therapies can also cause bowel irritation. We discuss bowel-related side effects more in chapter 10, but the important thing to remember is to watch your diet. Some patients find that diarrhea is more stable when they take Imodium every day. One of my patients loved to eat salad, but it made her diarrhea worse. She found that she could eat salad once a week, and just plan to take more Imodium on that day. But you may find that there are certain foods that you can’t eat while in treatment.

Hair loss. Remember that not all chemotherapy causes hair loss, and you’ll have to ask your doctor whether you can expect this side effect. Thinning hair typically starts to be noticeable about three weeks after the beginning of a regimen. You may notice clumps of hair in the shower or on your pillow in the morning. Some regimens cause significant (short-term) hair loss, and you may want to keep a close-cropped haircut or even be fitted for a wig near the start of your treatment. Remember that it’s temporary. Your hair will grow back, but this can feel like the first of many ways in which the cancer and its treatment change your body and your sense of self. You can read more about this aspect of living with cancer in chapter 8.

Mouth sores. One common side effect of chemotherapy is the tendency to get small mouth sores for a few days after infusion. This is often called mucositis (inflammation of the mucus membrane). Some chemotherapy regimens cause irritation in the mucus membranes inside the mouth, or sometimes they activate a previous herpes infection. These are a nuisance, although they typically heal quickly, but if they cause enough pain that you have trouble swallowing or opening your mouth or eating, you should contact your doctor.

Other Side Effects

Part II of this book details the most common ongoing side effects of treatment and how to manage them more effectively.

Some side effects can be permanent, and you will want to be informed about these as well. I recently had a patient who was an orthopedic surgeon. Cyndi loved operating, but her chemotherapy regimen came with a 20 percent chance of developing a permanent neuropathy (tingling or numbness in the hands and feet), which could affect her ability to operate. We could have chosen a less effective regimen that didn’t have neuropathy as a side effect. In the end Cyndi decided to take her chances with the more effective regimen, and she thanked me for bringing it up as she started to mentally prepare for a life that might not include performing operations.

Planning Your Life after Infusions

Side effects tend to have a common rhythm. Many of my patients will say that they feel pretty crummy for the first two to three days immediately after the infusion. Many of them feel tired and sleep most of the first day after infusion. If the nausea is well controlled, they won’t feel sick, but they won’t feel like eating, either. Patients tend to feel better with each subsequent day after that until they are feeling much more like themselves. Depending on the structure of your cycle of chemotherapy, you may feel great for two weeks between infusions, or if you are on a weekly regimen, you might have only a few days that you feel like yourself.

Once you get a sense of how you are going to respond to a specific chemotherapy, you may decide a certain day is better for the infusion. Some people like infusions early in the week so they are feeling better by the weekend, while others like the infusions later in the week so they can hunker down over the weekend and then feel better during the week. One of my patients was a nurse who loved her job so much that she didn’t want to stop working while being treated for stage 4 ovarian cancer. She didn’t want to stay home the week after her infusions. She found that she preferred to get each infusion on a Friday, so that she could deal with fatigue over the weekend. By Tuesday, she would feel good enough to return to work, although she still needed rest times during the day. She was able to schedule her shifts so that she had a longer break at lunch and could rest for a couple of hours in the middle of the day that first week. By the second week after each infusion, she felt good enough to resume her usual work schedule.

There are no right or wrong answers. Just think about what might work best for you, and know that the clinic should be able to adapt to the schedule you prefer.

Additional Support

Starting treatment is always challenging, and more often cancer centers are including supportive services to help you relieve stress and ease into the cadence of chemotherapy. These might include massage, acupuncture, music or art therapy, or time with a social worker or religious counselor. Your palliative care team and your infusion nurses will be a great source for additional therapies available both inside the cancer clinic and within the community.

Everybody needs a break sometimes, even in the middle of a chemotherapy regimen. You may have an important trip planned or a family gathering for which you want to feel as much like yourself as possible. Many people benefit from having a little time away from chemotherapy. You can always discuss the option of delaying a treatment to accommodate a life event or special trip. These delays are often called chemo holidays, and oncologists understand that cancer treatment is one part of your life, but not your whole life. You should be able to take a break if you need one.

For those patients on lifelong chemotherapy, these breaks in treatment can be wonderful, even if not tied to a specific event. Some are extended breaks from treatment that last for several months. This will give you some time to feel normal again without having to spend time in the infusion unit. If you are receiving lifelong chemotherapy, you should definitely ask about the possibility of a chemo holiday. If you have a curable cancer, there may be excellent reasons why your doctor will not want you to take a break from chemo.

Fertility and Chemotherapy

Going through chemotherapy can affect your fertility, and if you are concerned about remaining fertile after treatment, you will want to talk to your doctor about how your body may be affected by treatment. Some women harvest eggs and some men bank sperm before starting chemotherapy. You want to think about the future if having children is a priority for you.

How Chemotherapy Affects the Family

One of the unpredictable side effects of chemotherapy is how it affects the whole family. Whether it’s your spouse, children, parents, or siblings, people will react differently to your chemotherapy because they want to help but don’t know how. These are incredibly stressful times for families. Everyone wants to do the right thing, but some things are more helpful than others. I am going to list some of the tricky issues that come up for patients and families. They may or may not apply to you.

Over the years, I have found some things help treatment go more smoothly. First, have one or two people who come to all of your appointments (or as many appointments as possible). One of them should be the agent of your health care proxy. This is crucial. You need to designate a person to make medical decisions for you if you are too sick to make them yourself. This person should be present for nearly every appointment so that he or she hears the same information that you are hearing. It is also important to talk about your wishes for treatments with this person.

During these appointments your loved ones have the opportunity to ask as many questions as they like. You can encourage a discussion about any of the issues they have been bugging you about. Sometimes it is helpful for them to hear the same message from your team that you are telling them. Sometimes they will want more or less information than you want to hear. This is normal. Your spouse or your sister might want to know everything about what might happen if treatment doesn’t go as well as we hope, and you may not. Or you might want to know about what might happen if the cancer progresses, while they want to hear nothing about it. Your medical team knows that you get to decide how much information you want to have about the future. And you can work with your team to get everyone’s needs met.

I had a patient, Rick, who wanted to know as much information about the future as possible while his wife was feeling particularly overwhelmed and didn’t want to think about anything but the current treatments. I would meet with the family at first, and then when Rick had additional questions, he and his daughter would stay to talk with Dave and me while his wife went for coffee.

You may have a larger group of people you want to meet the oncology team as well. It is fine to talk to your oncologist about having periodic family meetings so everyone can ask their questions. These often make sense when it is time to change to a new chemotherapy.

These family meetings are different from the clinic appointments that take place on the day of each infusion. Your infusion-day appointments become fairly routine after a while. It might be nice to have someone with you to pass the time, or it may be necessary to have someone drive you home if you are feeling crummy, but in the appointments before each infusion, your doctor will not usually be providing new information about how the treatments are working. For those appointments when your doctor will be reviewing scans or talking about treatment options, you may want to invite different people to join you, so that everyone hears the same information at the same time.