You need only reflect that one of the best ways to get yourself a reputation as a dangerous citizen these days is to go about repeating the very phrases which our founding fathers used in the struggle for independence.

Guess who has more political power in a democracy—an individual who can cast a single vote once every few years, or a major corporation that can shower politicians with campaign donations and other monetary favors any day of the week?

As much as the powers that be would like you to believe that your vote actually counts (when it's not being lost by a voting machine), the reality is that most individuals feel powerless and helpless in the face of lobbyist groups and corporate influence. That's why desperate people often resort to violence to force governments to deal with long-standing problems. For example, blacks protested against racial inequality during the April 1992 Los Angeles riots (sparked by the acquittal of four white police officers accused of beating Rodney King), and French immigrants rioted in October 2005 to protest high unemployment rates and police brutality in their community. Before riots brought attention to these issues, the problems were largely ignored by the governments that should have been actively looking for solutions.

Rather than waiting until situations reach such a boiling point, many individuals channel their energy into activist organizations. Before the Internet, activists had to rely on meetings, newsletters, and mass mailings to attract supporters and to keep their members organized and informed. However, the Internet has given them a medium for spreading their ideas and publicizing their goals to a worldwide audience.

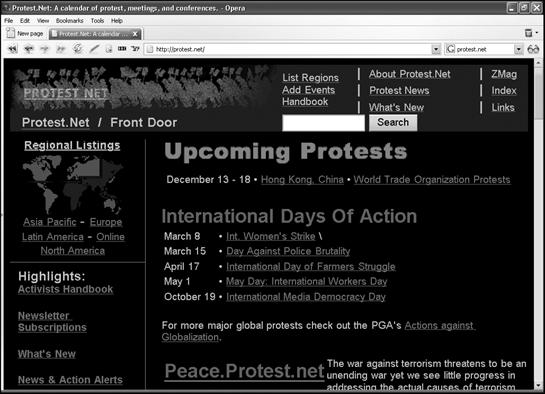

To learn more about using the Internet to form or improve an activist group, read The Virtual Activist, a training course offered by NetAction (www.netaction.org). If you want to find a protest rally near you, visit Protest.Net (www.protest.net), which lists events around the world and offers an Activist Handbook to help people get involved, as shown in Figure 16-1.

Email, websites, and instant messaging let activists communicate faster and more conveniently, but the real promise (or threat) of the Internet is as a protest medium in and of itself. The Internet provides the opportunity for virtual sit-ins and blockades, email bombing, web page defacing, and the creation and spread of worms and viruses for a cause.

Figure 16-1. Protest.Net lists different events by geographic location, date, and topic so you can demonstrate around the world at your convenience.

One common form of protest involves physically taking over or blocking access to an area or a building, such as the April 9, 1969, takeover of a Harvard University administration building by 300 students protesting the Vietnam War. Such sit-ins rarely cause any damage, but they help bring attention to the protesters' cause, especially if the protesters can occupy and shut down a high-profile target like Harvard. (Taking over and holding the men's room at a gas station in Barstow, California, wouldn't have quite the same dramatic effect, no matter how many people might be involved.)

Because physical takeovers can be difficult to organize, many activists engage in virtual sit-ins and blockades that anyone can join, no matter where they are. The goal of such virtual protests is the same as for their offline counterparts—to shut down access to a high-profile target and gain publicity.

On December 21, 1995, a group calling itself the Strano Network organized the world's first Internet strike with the following announcement:

BOIKOTT THE FRENCH GOVERNMENT'S INSTITUTIONS!

French Goverment has shown a total contempt for French people, for international community, for common people who just would like to grow up their sons in a better world as it:

goes on with nuclear experiments in Pacific Ocean's islands

goes on with use of nuclear energy as mainly source of "civil" energy

goes on with its projects of "social redrawing" without taking into account the enormous presence of people in recent demonstrations of protest against such kind of policy.

At a designated hour, the Strano Network asked that protesters visit a wide range of French government agencies' websites, including Le Ministere des Affaires Etrangeres (www.france.diplomatie.fr), Le Ministere de la Culture et de la Francophonie (http://web.culture.fr), and the OECD Nuclear Energy Agency (www.nea.fr). With such a massive flood of visitors, the Strano Network hoped to overwhelm the French government's webservers and knock their sites offline, which, according to some reports, they succeeded in doing.

What was unique about the world's first virtual sit-in was that it not only attacked a target and prevented legitimate users from accessing it, but it did so using completely legal methods. Participants in a physical sit-in risk arrest for trespassing, among other things, but there's nothing illegal about individuals visiting a single website simultaneously. The result, however, is a denial of service attack for which one individual person cannot be held responsible.

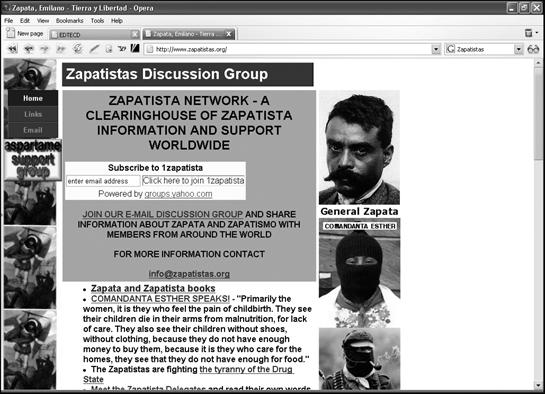

Few people know where Chiapas is (it's on the southern tip of Mexico), and even fewer people know who the Zapatistas are (they're the indigenous people of Chiapas, named for Emiliano Zapata, an early–20th-century Mexican revolutionary leader who fought for land and freedom for his people). All that changed on January 1, 1994, when the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) declared war against the Mexican state and demanded the liberation of the people of Chiapas and Mexico. As part of the Zapatistas' war declaration, they explained how the state of Chiapas was one of the poorest in Mexico, yet accounted for much of Mexico's oil wealth, along with exports of lumber, coffee, and beef.

The Zapatistas initially tried communicating their mission to the world through traditional news media, such as CNN and the Mexican state-controlled TV network, Televisa, but they found their letters, reports, and stories severely edited, which prevented others from understanding the true nature of their rebellion. Only the Mexican newspaper La Jornada published the Zapatistas' materials complete and unedited, but this newspaper rarely reached anyone outside of Mexico City. As far as the traditional news media were concerned, the Zapatistas didn't exist and most people reading the limited news coverage concluded that they were simply troublemakers who deserved to be put down.

Even when the Mexican government rushed in 15,000 troops to suppress the rebellion militarily, the media continued to downplay news about the Zapatistas, effectively muzzling their pleas for freedom and ignoring their reports of government suppression and exploitation. To circumvent the indifference of the traditional news media, Zapatista supporters started typing or scanning information from the group and distributing it over the Internet.

People translated the Spanish text into English and other languages, and soon the Zapatistas' plight began attracting attention from overseas newspapers and magazines that might never have bothered to cover the rebellion otherwise. When the Mexican Army surrounded 12,000 guerillas, the Zapatistas reported through the Internet that they had escaped the encirclement and conquered several nearby villages, which caused confusion in world markets and brought about a sudden drop in the value of the Mexican peso. As more independent news media sources confirmed the Zapatistas' claims (to the embarrassment of the Mexican government), the Zapatista movement gained more credibility and garnered more interest. In this case, the Zapatistas didn't have to stage a virtual sit-in to publicize their plight; they simply used newsgroups, email, and websites to broadcast the Zapatista struggle to the rest of the world.

To learn more about the Zapatistas, visit the Zapatistas Network (www.zapatistas.org), shown in Figure 16-2, or Chiapas Watch (www.zmag.org/chiapas1).

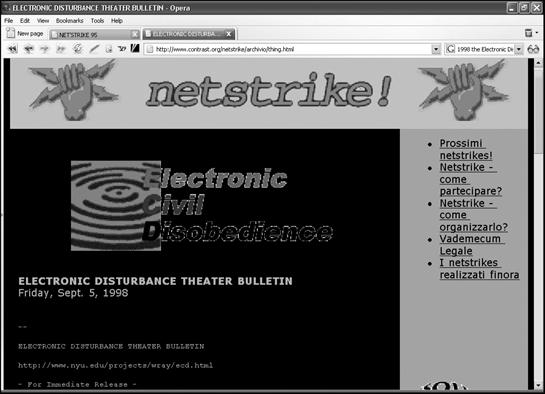

A group calling itself the Electronic Disturbance Theater (www.thing.net/~rdom/ecd/EDTECD.html) has taken the Zapatistas' cause to a new level by developing virtual activism software and organizing Internet strikes, as shown in Figure 16-3.

To organize its Internet strikes, the Electronic Disturbance Theater created a special Java applet dubbed FloodNet that participants could install to reload the target websites automatically every few seconds. According to the Electronic Disturbance Theater, more than 10,000 people from all over the world participated in the Internet strike on September 9, delivering 600,000 hits per minute to each targeted site using FloodNet.

Figure 16-3. On September 5, 1998, the Electronic Disturbance Theater called for an Internet strike against the Pentagon, the Frankfurt Stock Exchange, and Mexican President Zedillo's website to support the Zapatistas.

When the Pentagon detected FloodNet's attacks, it redirected FloodNet users to another web page with a Java Applet program called HostileApplet, which would endlessly reload a document in the participant's browser, effectively tying up his computer and preventing him from attacking the Pentagon's site.

President Zedillo's site didn't retaliate during the September 9 attack, but later, during a similar attack the following June, his site caused protesters' browsers to keep opening windows until their computers crashed. Despite these countermeasures, the Electronic Disturbance Theater declared their second Internet strike a success too, noting that "our interest is to help the people of Chiapas to keep receiving the international recognition that they need to keep them alive."

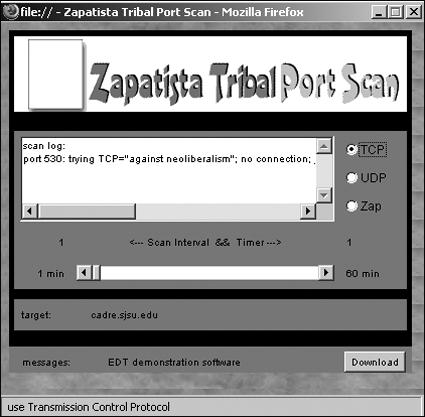

On January 3, 2000, Zapatista supporters wrote messages to the Mexican soldiers fighting to suppress the Zapatista rebellion, folded these messages into paper airplanes, and then launched the Zapatista "Air Force." To commemorate this event, the Electronic Disturbance Theater created the Zapatista Tribal Port Scan (ZTPS) program, which works in a similar way by scanning a random port on a target computer and sending it a text message as shown in Figure 16-4.

Besides the Zapatistas, the Electronic Disturbance Theater has supported a variety of other causes as well. To oppose US military strikes and economic sanctions against Iraq, the Electronic Disturbance Theater used its FloodNet program to attack the White House website, and in January 1999, it also helped organize animal-rights activists to protest different websites in Sweden. If you have a cause that needs worldwide publicity, consider contacting the Electronic Disturbance Theater for help.