Like most criminals, hackers often bring about their own downfall by failing to remove all traces of their crime. Not only do many hackers leave incriminating notes and printouts of their latest exploits scattered around, but they also can't resist bragging about their exploits in public chat rooms. Yet even this blatant indiscretion wouldn't be so damaging if these same hackers didn't unwittingly leave incriminating evidence stored all over their own computers too.

The biggest difference between electronic data and traditional data is that once you store electronic data on any form of magnetic media, it can stay there much longer than you expect. To understand how it's possible to recover a file that's been deleted, you need to understand how computers store and organize files on a disk.

When a computer stores information on a disk, it can't just toss it anywhere, because that would make it difficult to find it again—it would be like throwing your socks on your bedroom floor and then wondering why you can never find a matching pair when you need one. To help organize data, computers divide disks into multiple tracks, which you can think of as circular storage bins on the surface of a disk.

Each track is divided into smaller parts called sectors. A group of sectors is called a cluster. When you save data to your disk, your computer stores your file in multiple sectors. When you add or delete data from a file, the total number of sectors used to store your file grows or shrinks accordingly. Basically, a sector is a tiny box that contains part of a single file.

Ideally, your computer tries to store files as one continuous track, which allows it to retrieve data quickly. However, the more you save, edit, and delete files, the more likely it is that the computer will have to store one part of a file in one sector and another part of that same file in another sector, on a completely different part of the disk. When you defragment your hard disk, you're essentially rearranging all your files so the data from each file gets stored in adjacent sectors once more.

To keep track of which sectors contain which files, every disk contains a special directory, sometimes called a File Allocation Table (FAT) or a Master File Table (MFT). The FAT or MFT (or whatever name your particular computer uses) lists all the files stored on the disk along with pointers that identify the exact tracks and sectors that contain each file.

When you delete a file, your computer takes a shortcut. Instead of physically destroying the data, the computer simply erases its existence from the disk's directory, which pretends that the file no longer exists, although the contents of the file are still intact. Only when the computer needs the space taken up by the deleted file will it actually overwrite the old information with new data. This is like taking your name off your apartment building's directory when you move out, but leaving your unwanted belongings behind in your old apartment. Only when someone else moves in do the old contents of the apartment get thrown out.

If your disk has plenty of extra space available, you could go weeks, months, or even years before the data in those deleted sectors is overwritten. (You can accomplish almost the same thing as overwriting the data, however, by defragmenting your hard drive regularly.)

You can usually retrieve a trashed file by running an undelete utility program right away. An undelete utility simply changes the disk directory to identify any "deleted" files, so that the computer will recognize the files again. Of course, the longer you wait to run the utility, the more likely your computer will have overwritten some, or possibly all, of a particular deleted file's contents with new data, making it difficult, if not impossible, to recover the original contents.

Some utility programs, such as the Norton Utilities, come with a file-deletion protection feature that saves any deleted files in a special folder so that you can quickly and accurately recover them any time in the future. Obviously, this feature can be a lifesaver if you accidentally delete something important, but it can also work against you by preserving sensitive files you thought you got rid of months ago.

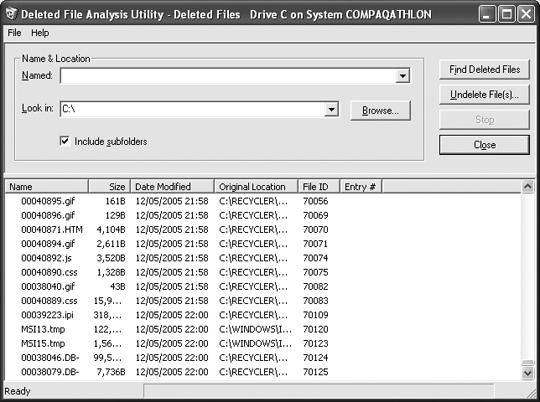

To find an undelete program, try Norton Utilities (www.symantec.com), Active@DELETE (www.active-undelete.com), Restorer 2000 (www.bitmart.net), or Undelete (www.execsoft.com). Executive Software, the maker of Undelete, also offers a free Deleted File Analysis Utility (see Figure 22-1), which examines your hard disk to see how many deleted files may still be recoverable. The results may surprise you.