Depending on the seriousness of the crime and the importance of recovering the data stored on a disk, computer forensics experts generally rely on four basic tools when retrieving deleted data: file-undeleting programs, hex editors, and magnetic sensors and electron microscopes.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, file-undeleting programs, readily available with programs like Norton Utilities, are often sufficient to catch novices who attempt to get rid of incriminating files, such as pictures of child pornography. But they are only effective if the file contents have not already been overwritten on your hard disk, so undeleting programs are a relatively weak forensics tool.

Hex editors are special programs that let you peek at the physical contents stored on a disk. Programmers often use hex editors to modify or examine files, while hackers often use hex editors to peek inside copy-protected games so they can peel away the security or so they can modify the video game to find and turn on hidden features.

Hex editors can probe the contents of any disk. Instead of forcing you to view a disk's contents as organized into partitions, directories, and files, as usually shown to the user by an operating system, a hex editor lets you examine the contents of a disk in terms of its physical layout, such as scanning the surface of the storage media from the outer edges of the disk down to its inner edges.

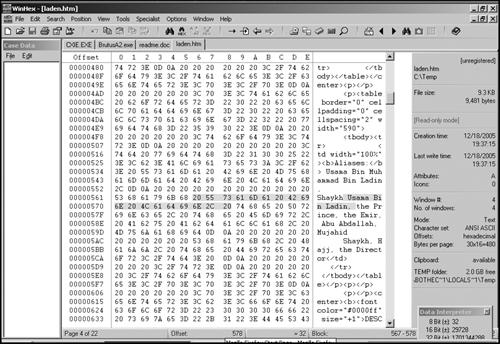

By using a hex editor, computer forensic specialists can identify and retrieve information that can't normally be accessed by the operating system. As shown in Figure 22-4, hex editors don't rely on operating system services to open and access "files." Instead, they display the physical disk area holding the contents of a file, using hexadecimal codes to represent the actual bytes of data.

Using a hex editor to examine an entire hard disk would be like scouring the inside of a skyscraper for fingerprints, so they're best used for searching only the specific parts of a drive where desired information may reside. Still, hex editors can often recover some or all of the data from a deleted file that you might not otherwise be able to access, such as in the slack space of a file. To see what a hex editor can find on your hard disk, download and try Hex Workshop (www.bpsoft.com), UltraEdit (www.idmcomp.com), WinHex (www.x-ways.net), or VEDIT (www.vedit.com).

No matter how many times you overwrite a file or format and partition a hard disk, traces of the original data may still remain. File shredders make it progressively more expensive and difficult to retrieve, but not impossible.

Every file you delete leaves residual magnetic traces of itself. Each time the computer overwrites a file's contents, the disk heads may be aligned slightly differently with respect to the surface of the media, and fragments of the deleted file may remain afterwards. Forensics experts can use sensors to measure the changes in magnetic fields on a disk's surface and then reconstruct part or all of the bytes in a deleted file, or they can use an electron microscope to do the same thing. Electron microscopes—extremely expensive but available to many governmental organizations—can also measure tiny changes in magnetic fields, left over from the original data, that not even overwriting can completely obliterate.

People may burn their floppy or hard disks, crush and mangle them, cut them into pieces, pour acid on them, and physically manhandle them in a myriad of ways, thinking there will be no possible way of using them on another computer again. However, even the physical destruction of a floppy or hard disk can't guarantee that the data has been safely destroyed, because government agencies such as the FBI and CIA are able to practice a specialized technique known as disk splicing. Disk splicing entails physically rearranging the pieces of a floppy or hard disk as nearly as possible back to its original condition. Then magnetic sensors or electron microscopes scan for traces of information still stored on the disk surface.

Obviously, disk splicing is a time-consuming and expensive procedure, so don't expect your local police force to have that kind of knowledge, skill, or equipment. But if you've destroyed evidence that might interest the NSA, CIA, or FBI, don't expect a mangled disk to hide your secrets from the prying electronic eyes of rich and powerful government agencies. In fact, the American government even has a special laboratory called The Defense Computer Forensics Lab (www.dcfl.gov), located in Linthicum, Maryland, which specializes in retrieving information from computers, no matter what condition of the hardware or disks.

The ultimate lesson to learn is that if you don't want to risk having information retrieved off your hard or floppy disk, your only absolutely foolproof option is to avoid storing it on any computer in the first place.