On December 24, 1851, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s brig Una wrecked at Neah Bay after having sheltered there for a few days. Even with both anchors down, the ship was blown by strong winds into Waadah Island at the opening of the bay. Bound from Fort Simpson, about five hundred miles to the north, to Fort Victoria at the southern end of Vancouver Island, the Una carried a load of furs and £300 worth of gold that the crew had collected from the Queen Charlotte Islands along the northern coast of British Columbia. Makahs salvaged stores, rigging, and other flotsam from the wreck of the 187-ton vessel. According to Northwest Coast ownership standards, chiefs of the People of the Cape (Makahs) owned whatever washed ashore at Neah Bay. Conflict erupted, however, when the Una’s crew and passengers attempted to prevent Makahs from exercising their salvage rights. In the fray, someone stabbed a passenger, Sudaał, daughter of a Gispaxlo’ots (Tsimshian) chief and wife of Fort Simpson’s chief trader, John Kennedy. A prominent individual in Northwest Coast and Hudson’s Bay Company societies, Sudaał was probably known by some of the People of the Cape; perhaps she was injured while attempting to use her high status to protect the ship’s cargo. Two American trading vessels, the Damariscove and Susan Sturges—also anchored in Neah Bay—intervened and took aboard the Una’s crew, passengers, and valuable cargo. As the survivor-laden ships departed, someone set fire to the wreck’s remains, demonstrating that the foreshore and sea around Cape Flattery was still Makah space.1

Two Makah leaders, Chiefs Yela ub (“yeh-luh-koob”) and

ub (“yeh-luh-koob”) and  isi·t (“klih-seet”), knew that they needed to make some effort to appease the King George men (British) of the Hudson’s Bay Company and officials of the nearby Vancouver Island Colony. The chiefs would have been eager to avoid having British gunboats shell Makah villages in reprisal. More important, they would have desired to maintain cordial relations with the company, which provided them with valuable trade goods that they used to maintain their authority among the People of the Cape and neighbors in the ča·di· borderland. They sent messages to James Douglas, HBC chief factor and governor of the colony, apologizing for their people’s conduct and offering to pay for the stolen and damaged property. As one of the chiefs explained, they were absent at the time of the incident, so they could not control the villagers. Recognizing an opportunity, Yela

isi·t (“klih-seet”), knew that they needed to make some effort to appease the King George men (British) of the Hudson’s Bay Company and officials of the nearby Vancouver Island Colony. The chiefs would have been eager to avoid having British gunboats shell Makah villages in reprisal. More important, they would have desired to maintain cordial relations with the company, which provided them with valuable trade goods that they used to maintain their authority among the People of the Cape and neighbors in the ča·di· borderland. They sent messages to James Douglas, HBC chief factor and governor of the colony, apologizing for their people’s conduct and offering to pay for the stolen and damaged property. As one of the chiefs explained, they were absent at the time of the incident, so they could not control the villagers. Recognizing an opportunity, Yela ub and

ub and  isi·t attempted to turn this incident to their advantage. By claiming their absence when the aggressive actions and violence occurred, they could point to the perpetrators as “bad” Indians while positioning themselves as the “good” chiefs with whom Douglas could work.2

isi·t attempted to turn this incident to their advantage. By claiming their absence when the aggressive actions and violence occurred, they could point to the perpetrators as “bad” Indians while positioning themselves as the “good” chiefs with whom Douglas could work.2

In fact, one Makah leader—probably Yela ub—performed his version of the “good” chief when the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Cadborough sailed into Neah Bay a month later, seeking restitution for damage to British property and pride.3 Instead of being cowed by this symbol of empire, he contained the threat by deploying customary Northwest Coast diplomacy. The Makah chief told Charles Dodd, the commander of the expedition, that he had already executed ten of the plunderers and burned alive the one accused of setting the vessel on fire. In reality, this leader had probably done nothing of the kind. If he had executed or immolated anyone, the individual would have been a slave. Within Northwest Coast societies, high-status individuals occasionally used slaves as proxies to pay for murders, property damage, and theft, a fact that Dodd, an experienced HBC employee, might have known. Although the Makah leader never offered up any physical evidence of the grisly justice, the Cadborough’s commander quietly accepted the chief’s assurances about punishing the perpetrators, thereby acknowledging this leader’s authority to punish his people for supposed crimes against British citizens and property. Yela

ub—performed his version of the “good” chief when the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Cadborough sailed into Neah Bay a month later, seeking restitution for damage to British property and pride.3 Instead of being cowed by this symbol of empire, he contained the threat by deploying customary Northwest Coast diplomacy. The Makah chief told Charles Dodd, the commander of the expedition, that he had already executed ten of the plunderers and burned alive the one accused of setting the vessel on fire. In reality, this leader had probably done nothing of the kind. If he had executed or immolated anyone, the individual would have been a slave. Within Northwest Coast societies, high-status individuals occasionally used slaves as proxies to pay for murders, property damage, and theft, a fact that Dodd, an experienced HBC employee, might have known. Although the Makah leader never offered up any physical evidence of the grisly justice, the Cadborough’s commander quietly accepted the chief’s assurances about punishing the perpetrators, thereby acknowledging this leader’s authority to punish his people for supposed crimes against British citizens and property. Yela ub then restored to the King George men every article of value that his people still possessed from the Una. Additionally, he offered an annual payment of whale oil as restitution. This leader had guessed that the expiations would result in the Cadborough’s departure from Makah waters without incident.4

ub then restored to the King George men every article of value that his people still possessed from the Una. Additionally, he offered an annual payment of whale oil as restitution. This leader had guessed that the expiations would result in the Cadborough’s departure from Makah waters without incident.4

While positioning himself as a broker of peace between King George men and the People of the Cape, Chief Yela ub followed indigenous protocols of Northwest Coast justice rather than acquiescing to British intimidation. A Native leader, not British officials, had “executed” the guilty Indians, and he paid the aggrieved party for the loss of property, as if making peace with another chief rather than suffering extortion from a coercive imperial agent. At this time, neither Great Britain nor the United States could apparently exercise Max Weber’s essential power of the state at Cape Flattery—neither could “lay claim to the monopoly of legitimate physical violence” at Neah Bay.5 Makah chiefs still held this power, despite Britain’s commercial hold on the area through the land-based fur trade and US territorial claims to the region. Yet Natives such as

ub followed indigenous protocols of Northwest Coast justice rather than acquiescing to British intimidation. A Native leader, not British officials, had “executed” the guilty Indians, and he paid the aggrieved party for the loss of property, as if making peace with another chief rather than suffering extortion from a coercive imperial agent. At this time, neither Great Britain nor the United States could apparently exercise Max Weber’s essential power of the state at Cape Flattery—neither could “lay claim to the monopoly of legitimate physical violence” at Neah Bay.5 Makah chiefs still held this power, despite Britain’s commercial hold on the area through the land-based fur trade and US territorial claims to the region. Yet Natives such as  isi·t and Yela

isi·t and Yela ub valued the trading relationship they had with the King George men, and they worried that the aggressive actions of some of their people jeopardized opportunities to benefit from the settler-colonial world of the mid-nineteenth century. Similarly, HBC employees, settlers, and colonial officials found themselves balancing retributive violence with reliance on local Indians, who provided the furs, supplies, and food that made colonialism possible in the Northwest Coast. Together these various stakeholders engaged one another and the new opportunities and challenges presented by the expanding settler-colonial world to meet differing needs of authority on the shifting grounds and waters of the borderlands.

ub valued the trading relationship they had with the King George men, and they worried that the aggressive actions of some of their people jeopardized opportunities to benefit from the settler-colonial world of the mid-nineteenth century. Similarly, HBC employees, settlers, and colonial officials found themselves balancing retributive violence with reliance on local Indians, who provided the furs, supplies, and food that made colonialism possible in the Northwest Coast. Together these various stakeholders engaged one another and the new opportunities and challenges presented by the expanding settler-colonial world to meet differing needs of authority on the shifting grounds and waters of the borderlands.

One set of changes revolved around the geopolitical claims to the region. From the 1770s through the 1840s, competing empires—including Russia, Spain, France, Great Britain, and the United States—drew boundary lines throughout the Pacific Northwest and attempted to reconfigure preexisting indigenous spaces, such as the ča·di· borderland, into places of commerce and empire. By the early 1820s, these overlapping colonial claims had simplified into the Oregon Country, a region whose joint occupation the United States and Great Britain made official through the Anglo-American Convention of 1818. According to the dominant historical narrative, the Pacific Northwest went from a borderland to a bordered land in 1846 when these two nations settled the boundary issue by creating a border from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean along the forty-ninth parallel and extending through the Strait of Juan de Fuca, cutting through Makah marine space. This transformation supposedly meant that the messy complexities of the colonial borderlands—embodied through the jointly occupied Oregon Country, the ambiguous identities of people living there, and the ethnic diversity and mixed-race world of the fur trade—settled into a tidy division between the US and British Wests.6 But the reality was not as neat as non-Native colonial and territorial officials desired because of the persistence of the ča·di· borderland’s characteristics.

Considering this period from a Makah perspective highlights not only continued indigenous agency and power but also the palimpsest nature of this borderland.7 New international boundaries, such as the one that separated the two halves of the Oregon Country, “remained dotted lines that took a generation to solidify.”8 When nation-states consolidated their power in the hinterlands, indigenous borderlanders supposedly lost autonomy. The metaphor of the palimpsest, however, allows us to uncover competing histories, such as those of the People of the Cape, whose actions demonstrate that the indigenous dynamics of the ča·di· borderland persisted longer than a single generation and after nation-state control grew. Paddling in canoes, trading, marrying, and fighting among the many villages of the Olympic Peninsula and Vancouver Island, Northwest Coast peoples demonstrated that the indigenous ča·di· borderland continued to exist alongside the colonial borderlands. Instead of there being one borderland zone with conditions shaped and controlled by newcomers and distant colonial officials, two layers of overlapping and interacting borderlands defined this space.

These geopolitical changes unfolded within the context of the land-based fur trade, an industry that shaped the lives of  isi·t and Yela

isi·t and Yela ub much as the maritime fur trade had done for previous chiefs in the ča·di· borderland. The new industry resembled its maritime antecedent because both depended on the complex, interconnected relationships among numerous peoples—both Native and non-Native—of the Northwest Coast. From the beginning of the land-based fur trade in the early nineteenth century, indigenous contributions allowed for non-Native survival and success, highlighting the way that different peoples, societies, and practices “imbricated” into the regional fabric of the Northwest Coast.9 Similar to the maritime fur trade, the land-based industry depended on safe, ordered spaces for profitable exchanges. But different strategies for creating safety and order marked the greatest contrast between the two trades, influenced the lives of local indigenous peoples, and altered the dynamics of power in the region. The land-based fur trade established long-term, terrestrial toeholds for non-Natives in the Pacific Northwest. Kernels of settlement, the HBC forts and the trade goods they provided made the company influential and drew new kinds of non-Natives to the region. During the 1840s, US and British settlers began establishing sawmills, fishing operations, farms, and small settlements in the region. Eager to protect these newcomers, the colonial governments of the United Kingdom and the United States grappled with policies for managing the large populations of Indians who still outnumbered whites.

ub much as the maritime fur trade had done for previous chiefs in the ča·di· borderland. The new industry resembled its maritime antecedent because both depended on the complex, interconnected relationships among numerous peoples—both Native and non-Native—of the Northwest Coast. From the beginning of the land-based fur trade in the early nineteenth century, indigenous contributions allowed for non-Native survival and success, highlighting the way that different peoples, societies, and practices “imbricated” into the regional fabric of the Northwest Coast.9 Similar to the maritime fur trade, the land-based industry depended on safe, ordered spaces for profitable exchanges. But different strategies for creating safety and order marked the greatest contrast between the two trades, influenced the lives of local indigenous peoples, and altered the dynamics of power in the region. The land-based fur trade established long-term, terrestrial toeholds for non-Natives in the Pacific Northwest. Kernels of settlement, the HBC forts and the trade goods they provided made the company influential and drew new kinds of non-Natives to the region. During the 1840s, US and British settlers began establishing sawmills, fishing operations, farms, and small settlements in the region. Eager to protect these newcomers, the colonial governments of the United Kingdom and the United States grappled with policies for managing the large populations of Indians who still outnumbered whites.

Influential Makah chiefs engaged trade and colonization in personal ways to maintain their ability to control space, and their actions helped to make colonialism possible in this region.10 By the 1850s, two Neah Bay chiefs—Yela ub and

ub and  isi·t—emerged as the Makah Nation’s faces to the settler-colonial world. Born in 1818 or 1819 to a prominent Makah trader, Yela

isi·t—emerged as the Makah Nation’s faces to the settler-colonial world. Born in 1818 or 1819 to a prominent Makah trader, Yela ub worked as a kitchen scullion at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Langley, located about thirty miles up the Fraser River, which empties into the eastern waters of the ča·di· borderland. There he learned English and lived among King George men who gave him a new name, Flattery Jack, and likely treated him poorly due to his age, race, and position in the kitchens. After someone murdered his father in 1831, the teenage Yela

ub worked as a kitchen scullion at the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fort Langley, located about thirty miles up the Fraser River, which empties into the eastern waters of the ča·di· borderland. There he learned English and lived among King George men who gave him a new name, Flattery Jack, and likely treated him poorly due to his age, race, and position in the kitchens. After someone murdered his father in 1831, the teenage Yela ub took over the family trading activities, traveling throughout the borderlands and beyond to exchange animal skins, ha·ykwa (dentalia shells used as currency), and slaves. Largely through trading, Yela

ub took over the family trading activities, traveling throughout the borderlands and beyond to exchange animal skins, ha·ykwa (dentalia shells used as currency), and slaves. Largely through trading, Yela ub rose to power among the People of the Cape, and he cultivated ties with several HBC personnel, who commonly called the village at Neah Bay “Flattery Jack’s Village.” There, he and his extended family lived in a longhouse that was about a hundred feet long by 1850, an indication of his high status.11

ub rose to power among the People of the Cape, and he cultivated ties with several HBC personnel, who commonly called the village at Neah Bay “Flattery Jack’s Village.” There, he and his extended family lived in a longhouse that was about a hundred feet long by 1850, an indication of his high status.11

Known to non-Natives as “the White Chief” because of his light complexion and Russian heritage through his father,  isi·t competed against Yela

isi·t competed against Yela ub and other chiefs for authority among the People of the Cape. Born sometime between 1807 and 1812, he came of age as a whaler just as US and British coastal traders began purchasing large quantities of whale oil from Makahs. After the 1846 death of George, the previous ranking Makah titleholder,

ub and other chiefs for authority among the People of the Cape. Born sometime between 1807 and 1812, he came of age as a whaler just as US and British coastal traders began purchasing large quantities of whale oil from Makahs. After the 1846 death of George, the previous ranking Makah titleholder,  isi·t used the wealth garnered from whale oil to secure his position as the highest chief among the People of the Cape. He also married the sister of S’Hai-ak (“s-hay-uhk”), a prominent chief among the neighboring S’Klallams, a move that restored peaceful relations between the two tribal nations. Probably to counter the influence of Yela

isi·t used the wealth garnered from whale oil to secure his position as the highest chief among the People of the Cape. He also married the sister of S’Hai-ak (“s-hay-uhk”), a prominent chief among the neighboring S’Klallams, a move that restored peaceful relations between the two tribal nations. Probably to counter the influence of Yela ub,

ub,  isi·t sought closer ties with Bostons (Euro-American officials and traders) by the early 1850s.12

isi·t sought closer ties with Bostons (Euro-American officials and traders) by the early 1850s.12

During the second quarter of the nineteenth century, Yela ub’s and

ub’s and  isi·t’s actions reveal aspects of Makah politics. The People of the Cape employed customary Northwest Coast leadership strategies to maintain their people’s autonomy in the face of mounting settler-colonial pressure, such as the racialized nature of power in this emerging colonial borderland. During the mid-nineteenth century, however, Native deaths from epidemics combined with increasing numbers of non-Native immigrants to change the demographics of the region and undercut the ability of Indians to define and control space on indigenous terms. In the years following the burning of the Una, a suite of diseases hammered the People of the Cape and other Native borderlanders. These catastrophes threatened to unravel the networks of kinship and trade that bound together the many peoples of the ča·di· borderland; that this did not occur is a testament to the resilience of the Makahs and their neighbors.

isi·t’s actions reveal aspects of Makah politics. The People of the Cape employed customary Northwest Coast leadership strategies to maintain their people’s autonomy in the face of mounting settler-colonial pressure, such as the racialized nature of power in this emerging colonial borderland. During the mid-nineteenth century, however, Native deaths from epidemics combined with increasing numbers of non-Native immigrants to change the demographics of the region and undercut the ability of Indians to define and control space on indigenous terms. In the years following the burning of the Una, a suite of diseases hammered the People of the Cape and other Native borderlanders. These catastrophes threatened to unravel the networks of kinship and trade that bound together the many peoples of the ča·di· borderland; that this did not occur is a testament to the resilience of the Makahs and their neighbors.

THE LAND-BASED FUR TRADE AND RISE OF THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY, 1811–1848

Native responses to the rising presence of King George men and Bostons transformed the ča·di· borderland into the sociopolitical region in which  isi·t and Yela

isi·t and Yela ub emerged as Makah leaders. Beginning in the 1810s, Makahs and other indigenous peoples of this marine borderland encountered more people from outside the Northwest Coast. Provided to non-Natives by various indigenous peoples, a wealth of natural resource commodities—furs, fish, whale oil, timber, and coal—drew newcomers to the region during the first half of the nineteenth century. Both

ub emerged as Makah leaders. Beginning in the 1810s, Makahs and other indigenous peoples of this marine borderland encountered more people from outside the Northwest Coast. Provided to non-Natives by various indigenous peoples, a wealth of natural resource commodities—furs, fish, whale oil, timber, and coal—drew newcomers to the region during the first half of the nineteenth century. Both  isi·t and Yela

isi·t and Yela ub developed ties to the most powerful newcomer, the Hudson’s Bay Company, as the People of the Cape became one of the key indigenous peoples central to the company’s regional success. When HBC forts appeared in the Northwest Coast, the young

ub developed ties to the most powerful newcomer, the Hudson’s Bay Company, as the People of the Cape became one of the key indigenous peoples central to the company’s regional success. When HBC forts appeared in the Northwest Coast, the young  isi·t and Yela

isi·t and Yela ub confronted the company’s efforts to produce and control space in and around the outposts. During this period, HBC officials at the forts employed retributive violence against Indians for supposed depredations on whites and their property. This established a precedent for the racialized nature of settler-colonial power that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century.13 Yet Makah chiefs such as

ub confronted the company’s efforts to produce and control space in and around the outposts. During this period, HBC officials at the forts employed retributive violence against Indians for supposed depredations on whites and their property. This established a precedent for the racialized nature of settler-colonial power that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century.13 Yet Makah chiefs such as  isi·t and Yela

isi·t and Yela ub retained enough power to interrupt imperial processes at least until the early 1850s.

ub retained enough power to interrupt imperial processes at least until the early 1850s.

From the beginning, the new iteration of the fur trade presented Makahs with competition and opportunity, a pattern that carried through many of the later changes the People of the Cape faced. Although established during the maritime fur trade, Fort Astoria became the first land-based fur trade outpost at the edge of the ča·di· borderland. Having made his fortune in the Northeastern fur trade after emigrating from Germany to the United States, John Jacob Astor financed the Pacific Fur Company (PFC), whose employees erected Fort Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River in 1811. Astor planned to collect furs from Indian hunters around the Columbia basin, ship the pelts to China, and exchange them for valuable products that could then be sold to US consumers. But Astor focused even more on attempting to monopolize provisioning the Russian-American Company’s settlements to the far north, thereby undercutting the incentive for potential competitors in the North Pacific. His plans went far beyond “calculations of profit”—he sought to extend US political and economic dominion beyond the Rockies, which would inhibit the expansion of his primary competitors, the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company, into the Pacific Northwest. But the early loss of the Tonquin, en route to the Russian outpost of New Archangel (Sitka, Alaska) to deliver a load of gunpowder and additional goods, and other difficulties stymied Astor’s plans. By the fall of 1813, in the midst of the war between Britain and the United States, the Pacific Fur Company’s partners at Fort Astoria decided to abandon the enterprise. They sold the fort and the company’s goods and furs to the North West Company, and many of the personnel stayed on with the new owners. With no other land-based operations to contend with at this point, the newly renamed Fort George continued to be an important hub during the waning years of the maritime fur trade.14

Drawn by the trade’s opportunities for goods and labor, indigenous peoples both local and from farther away proved central to the success of the land-based fur trade. The Tonquin brought a dozen Kanakas (Native Hawaiians) to the Columbia River basin, and the Pacific Fur Company’s Beaver brought another sixteen to Fort Astoria in May 1812. In addition to helping to construct and maintain the fort, these men played a critical role in sustaining the Astorians by crewing vessels, felling trees, clearing land, tending livestock, maintaining the post garden, foraging for edibles, hunting deer and elk, and fishing.15 The Astorians and their Kanaka employees would have failed from the beginning had they not received the consent and assistance of local Native leaders, such as Chiefs Concomly (Chinook) and Coalpo (Clatsop). Already adept at handling non-Natives through the maritime fur trade and Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery, which wintered at the mouth of the Columbia River from 1805 to 1806, Concomly and Coalpo understood the advantages to be gained from a local fort to which they could control access. Chinooks, Clatsops, and other Lower Columbia peoples protected the Astorians from hostile Indians, piloted ships across the treacherous sandbars of the river, passed on news and intelligence of regional events, and guided trade and reconnaissance expeditions into the interior and along the coast. They also performed more quotidian assistance as porters, hunters, gatherers, and fishers; women sold Astorians hats, moccasins, and baskets. As Alexander Ross, one of the fort’s clerks, complained, they “had to depend at all times on the success or good-will of the natives.” The Astorians’ amicable relationships often depended on their intimacy with Native women of rank and power. Daughters of prominent chiefs married white employees of the fort, and these exogamous relations fostered commercial ties and strategic alliances vital for the outsiders’ survival and success.16

Although they lived two hundred miles away, Makahs saw Fort Astoria as a potential trade competitor and just another small polity, one of several “little sovereignties” that composed indigenous Oregon from 1792 to 1822.17 During a reconnaissance to lands and peoples along the coast, Robert Stuart, a junior partner in the Pacific Fur Company, received warnings from Quinaults of a numerous and “wicked” nation to the north that “kill a great many Beaver & dispose of them (as well as the Quinhalt people, of their sea otter, of which they kill a considerable number) to the Neweetians for Hyquoyas.” Quinaults were likely referring to Makahs, who leveraged exchange and kinship networks to control the flow of furs, slaves, ha·ykwa, and other goods from peoples living between the mouth of the Columbia River and Nahwitti, a Tlatlasikwala Kwakwaka’wakw village at the northern tip of Vancouver Island. During the summer months, Indians from the north visited Baker’s Bay on the northern side of the Columbia’s mouth to fish and trade. Concomly warned PFC officials that these visitors were trying to encourage Chinooks to assist them in destroying the fort. Astorians conflated most northern Indians into “Neweetie Indians” and assumed that they were from Vancouver Island, although these northern visitors were more likely Makahs. Not only did they have marriage ties with Concomly’s Chinook family and make regular trips to the Columbia River, but they also would have had a significant motivation to attack interloping competitors.18

Although initially plotting to attack Fort Astoria, by 1816, Makahs had decided that without Chinook support, they were better off selling furs to these white traders on the Columbia, who by then were Nor’westers, employees of the North West Company. Peter Corney, an English sailor, noted that a group of Indians from Classet (Makahs) often camped at Baker’s Bay from June to October to cure salmon and sturgeon and to sell beaver and sea otter skins to Fort George, formerly Fort Astoria. Despite their decision to trade with the King George men, Makahs made it clear that they were a powerful people whom the outsiders should respect. Corney noted that “they are a very warlike people, and extremely dangerous, taking every advantage if you are off your guard.” Makahs continued to exchange furs with non-Native traders at the mouth of Columbia throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.19

With the support of the British government, the Hudson’s Bay Company absorbed the rival North West Company in 1821 and acquired Fort George. The company then began an aggressive expansion in the Pacific Cordillera stretching from the Columbia River to northern British Columbia, establishing fourteen posts between 1821 and 1846. Reflecting the shifting geography of the fur trade, in 1825 the company replaced the coastal Fort George with Fort Vancouver, located ninety miles upriver along the northern bank of the Columbia River, to better access inland exchange networks and the beaver skins they provided. The new fort became the Hudson’s Bay Company’s administrative headquarters and supply depot west of the Rocky Mountains. It also became home to an increasingly diverse population. After a visit in the winter of 1846–47, the Canadian artist Paul Kane described Fort Vancouver as “quite a Babel of languages, as the inhabitants are a mixture of English, French, Iroquois, Sandwich Islanders, Crees and Chinooks.”20 Like its predecessor, Fort Vancouver lay at the southern extent of the ča·di· borderland, “dropped into … [the] fully formed system of Chinook and Salish trade and culture,” by which it continued to receive furs from coastal peoples.21

Although the Hudson’s Bay Company set out to monopolize the industry in the Pacific Northwest, US competition provided indigenous peoples with even more trade options. Based out of New England ports, small “coasters” frequented the southern side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Puget Sound, and the Pacific shores to the mouth of the Columbia River. The brig Owhyhee entered the Columbia River in 1827, even sailing up to Fort Vancouver in an attempt to intercept furs bound for the HBC headquarters. Fearing potential losses from American coasters, Chief Factor John McLoughlin sent a crew to the mouth of the Fraser River at the eastern end of the ča·di· borderland to establish a new post, Fort Langley, in the fall of 1827. Reflecting a pattern typical of HBC workforces, this construction crew included one Abenaki from northeastern North America, two Native Hawaiians, one “York Factory Indian” from the shores of Hudson Bay, two Iroquois from upstate New York, and one “Canadian Half breed.” The Hudson’s Bay Company began collecting beaver skins from local Coast Salish peoples, Vancouver Island communities, and S’Klallams on the southeastern edge of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Fort Langley also drew Native laborers to the Fraser River area. They cleared land, provided large quantities of fish, cut timber and firewood, and performed other tasks important for the fort’s survival. Shortly after the establishment of Fort Langley, an influential Makah trader arranged to have his ten-year-old son, Yela ub, work in the kitchens.22 Yela

ub, work in the kitchens.22 Yela ub’s father probably wanted his son to learn English and to gain a better understanding of the culture of King George men in order to benefit his people’s commercial dealings with the newcomers.

ub’s father probably wanted his son to learn English and to gain a better understanding of the culture of King George men in order to benefit his people’s commercial dealings with the newcomers.

Other goods that Native peoples brought to Fort Langley outpaced the value of furs collected there and became commodities in the developing transnational exchange networks crossing the Pacific. In the early nineteenth century, Americans were the first to pursue a strategy of diversification that catalyzed an economic transformation for the northeastern Pacific. Beginning in the mid-1810s, maritime fur traders from New England traded sailing vessels with Kamehameha I, first king of the Kingdom of Hawai‘i, for sandalwood, which they exported to Canton, where Chinese craftsmen made incense, medicines, and carvings from the wood. During the 1820s, US coasters carried spars from the Northwest Coast to Oahu and supplied Russian outposts in Alaska and Spanish missions in California with provisions. Eyeing the success of these small competitors, George Simpson, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s administrator of the Columbia Department, urged the company to diversify its economic activities by expanding into provisioning these growing Pacific markets, and Fort Langley occupied an important role in the efforts. When Honolulu became the base of the North Pacific whaling fleet during the second quarter of the nineteenth century, the company was well positioned to supply specialized naval stores and hardware—including sheet copper, sheathing nails, anchors, anchor chains, rolls of canvas, tar, black and white paint, pitch, varnish, paint brushes, iron hoops, copper bolts, salted pork, arrowroot, charts, and nautical almanacs—to vessels that visited the Oahu agency. This outpost in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i became the primary supplier of produce, cured salmon, and spars, commodities collected from Northwest Coast peoples. The outcome of Simpson’s plan pleased company officials in the Pacific Northwest. In 1832, Archibald McDonald, chief trader at Fort Langley, reported, “Our Salmon … is close upon 300 Barrels, & I have descended to Oil & Blubber too…. I am much satisfied with its proceeds myself.” In return for indigenous goods, HBC traders such as McDonald provided standard trade items like tea, rice, tobacco, molasses, sugar, and salt. More exotic goods requested by Northwest Coast chiefs included coral and Chinese-made sandalwood and camphor boxes, which became popular potlatch gifts. Native demands illustrated the complexity of early nineteenth-century Pacific trade networks. Not only were indigenous peoples suppliers of commodities, but they also were savvy consumers of Asian and European goods.23

By the second quarter of the nineteenth century, the regional economy depended on the trade among indigenous peoples and newcomers. Much as powerful chiefs had monopolized exchanges with vessels during the maritime fur trade, prominent Northwest Coast leaders controlled access to forts after they had been built on their lands or those of a weaker neighbor. Concomly, the ranking Chinook chief, and members of his family mediated many of the exchanges between Natives and traders at Forts Astoria and George during the first part of the nineteenth century. Cowichans, a powerful people at the eastern edge of the ča·di· borderland, controlled Native access to Fort Langley and prevented others, such as Makahs, from trading there, even though the Hudson’s Bay Company had built the post in Stó:lō territory.24

The People of the Cape circumvented Cowichan control over exchanges at Fort Langley by trading with HBC vessels when they stopped at Neah Bay. Shortly after the post’s founding in 1827, Cape Flattery emerged as “the critical spot” in Fort Langley’s trading area.25 Captain James Scarborough, who worked for the company for twenty years, so frequently visited Neah Bay that some colonial records called this body of water Scarborough Bay.26 Located between Nuu-chah-nulth peoples to the north and Coast Salish peoples to the east and south, the early nineteenth century Makahs continued to attract indigenous trade from all corners of the ča·di· borderland. Compared to surrounding parts of the Northwest Coast, valuable sea otters could still be found off Cape Flattery, where Makah men such as Yela ub and his father hunted them from canoes in the open sea and from behind blinds on coastal beaches. In addition to sea otter pelts and beaver skins from other parts of the borderlands, Makahs provided whale oil and bone, fresh fish, slaves, and ha·ykwa, shells they harvested from the deep seafloor by means of a long pole. Indicating its importance as a commodity, the chief traders at Fort Langley tallied the acquisition of “Cape Flattery oil,” whale oil that HBC ships often purchased at more than one hundred gallons at a time. They shipped much of it to London, where it was distilled into benzene to light homes and businesses.27

ub and his father hunted them from canoes in the open sea and from behind blinds on coastal beaches. In addition to sea otter pelts and beaver skins from other parts of the borderlands, Makahs provided whale oil and bone, fresh fish, slaves, and ha·ykwa, shells they harvested from the deep seafloor by means of a long pole. Indicating its importance as a commodity, the chief traders at Fort Langley tallied the acquisition of “Cape Flattery oil,” whale oil that HBC ships often purchased at more than one hundred gallons at a time. They shipped much of it to London, where it was distilled into benzene to light homes and businesses.27

Despite the rising presence and power of the Hudson’s Bay Company, the wealth of goods provided by Northwest Coast peoples continued to draw US coasters to the region through the 1830s. The presence of these small, private traders backed by New England capital frustrated HBC traders and strengthened the position of Indian traders who could—and did—hold out for more favorable prices. Many of these coasters stopped at Neah Bay to purchase furs, fish, and whale oil, thereby intercepting commodities that normally went to Fort Langley.28 The overall trade in Cape Flattery oil increased, and by 1852, Makahs sold more than thirty thousand gallons of whale oil (valued at more than $20,000) to passing HBC and American vessels, and the People of the Cape kept a similar amount for personal consumption and exchange with neighboring Indians. According to whaling returns provided by a Makah chief in the late 1850s, sixty thousand gallons of oil represented approximately twenty-six whales killed annually.29 At times, Makahs had so much whale oil on hand that the visiting ships lacked enough casks and had to turn away Indian traders.30 A successful whaler such as  isi·t would have been a primary supplier and overseen his people’s interactions with the Bostons and King George men when exchanging whale oil for trade goods at the cape.

isi·t would have been a primary supplier and overseen his people’s interactions with the Bostons and King George men when exchanging whale oil for trade goods at the cape.

The HBC answer to increasing competition—the building of more forts—entangled Makahs more closely with the company after the establishment of Fort Victoria in 1843. Earlier forts had appeared at the ča·di· borderland’s edges; Fort Victoria, however, was located squarely within the borderland, or “in the midst of the Natives’ world.” By 1843, the company had grown concerned about the boundary issue. Hudson’s Bay Company officials worried that the United States and Britain would place the border north of Fort Vancouver, which would leave their primary Pacific depot in US territory. They wanted a depot situated farther north in order to supply more easily the majority of their outposts in the northern Pacific Cordillera. During the 1820s and 1830s, several ships wrecked at the dangerous mouth of the Columbia River, resulting in the loss of years’ worth of trade goods, thereby undercutting the company’s ability to compete with American coasters. These reasons encouraged the HBC to erect a new outpost at the southern end of Vancouver Island. In addition to its advantages over Fort Vancouver, Fort Victoria lay close to the important fisheries in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Puget Sound, and the Fraser River. The new outpost also had easy access to ample lumber for construction, to good-quality land for expansion, and to a large Native population. The company assumed that Indians throughout the ča·di· borderland would construct the fort, sell food to HBC employees, supply goods for export, and provide a market for British imports.31

The establishment of Fort Victoria and its early operations highlight the way indigenous peoples were the cornerstone of HBC growth in the region. When charged with the task of constructing the fort in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Chief Factor James Douglas chose Camosun, a sheltered harbor on the southern tip of Vancouver Island, where Indians could beach their canoes easily. To Douglas, this site appeared appealing—even Edenic—because the Coast Salish Lekwungen set regular fires to maintain this as one of the region’s prime camas fields. After disembarking at Camosun, Douglas told the Lekwungen chiefs who owned the site that he desired to build a trading post on their land. Knowing that Fort Langley had benefited neighboring indigenous peoples along the Fraser River, the chiefs gave Douglas permission to build the fort and provided labor to help in its construction. Later that summer, the company brought to the new outpost wild Spanish cattle and workhorses from Fort Nisqually in Puget Sound. Lekwungens helped to care for the livestock, even taking them into their longhouses during severe winters. In the beginning, non-Natives often called Fort Victoria by its “Indian” name, Camosun, delaying the immediate tendency of Europeans to replace indigenous place-names and illustrating that early colonial places often occupied spaces where indigenous peoples continued to exercise power.32 Fort Victoria thrived because of the consent, labor, and support provided by nearby indigenous villages.

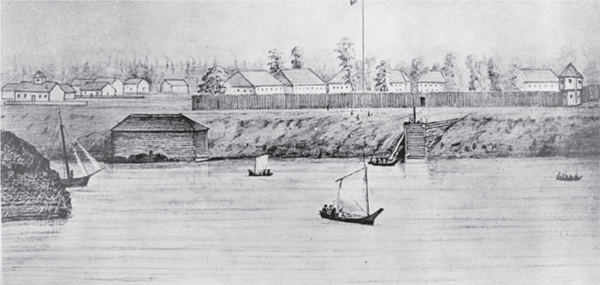

Fort Victoria, 1854. The artist captured the post’s marine connections with local Native communities by including Northwest Coast canoes, some with sails, traveling to and from the fort. Drawing by unnamed artist. Image A-04104 courtesy of Royal BC Museum, BC Archives.

Even more than they had with Fort Langley, the People of the Cape played a key role in Fort Victoria’s survival and early success. After construction began at Camosun, Makahs became regular visitors at the new HBC outpost, located just a short canoe paddle across the strait from their Cape Flattery villages. During Fort Victoria’s first summer and fall, Makahs and Nuu-chah-nulth peoples provided salmon and potatoes that fed the King George men and the Kanaka and Lekwungen laborers constructing the outpost.33 Just as important to the fort’s success, though, were the commercial products brought there by the People of the Cape and other indigenous communities. Makah chiefs, such as Yela ub and

ub and  isi·t, visited the fort with their people to sell fish, furs, and whale oil.34 Other borderlanders also brought goods to the fort, including enormous quantities of salmon, cedar shingles by the thousands, and canoe-loads of blueberries. The Hudson’s Bay Company earned a substantial margin of profit from these indigenous commodities by funneling them into the Pacific market that provisioned miners in California and the growing urban center of San Francisco. Douglas estimated that in 1854 Fort Victoria exported ten thousand gallons of Native-produced oil to California, where it fetched two to three dollars per gallon.35 Acknowledging the advantageous location of Fort Victoria and its rising importance in the provisioning trade, the Hudson’s Bay Company made it the company’s Pacific depot and headquarters in 1849. The commodities that

isi·t, visited the fort with their people to sell fish, furs, and whale oil.34 Other borderlanders also brought goods to the fort, including enormous quantities of salmon, cedar shingles by the thousands, and canoe-loads of blueberries. The Hudson’s Bay Company earned a substantial margin of profit from these indigenous commodities by funneling them into the Pacific market that provisioned miners in California and the growing urban center of San Francisco. Douglas estimated that in 1854 Fort Victoria exported ten thousand gallons of Native-produced oil to California, where it fetched two to three dollars per gallon.35 Acknowledging the advantageous location of Fort Victoria and its rising importance in the provisioning trade, the Hudson’s Bay Company made it the company’s Pacific depot and headquarters in 1849. The commodities that  isi·t, Yela

isi·t, Yela ub, and others exchanged at Fort Victoria helped to transform this outpost into a prosperous commercial hub and provisioned colonial activities throughout the Pacific.

ub, and others exchanged at Fort Victoria helped to transform this outpost into a prosperous commercial hub and provisioned colonial activities throughout the Pacific.

While providing commercial opportunities for Native traders, the presence and actions of the Hudson’s Bay Company in the ča·di· borderland exacerbated existing tensions among the indigenous peoples, much as the maritime fur trade had done earlier. Unlike the previous industry, in which vessels—sometimes several at a time vying for the attentions of Native traders—anchored for short periods of time off villages, the land-based fur trade established long-term trading opportunities in the homelands of specific indigenous groups. Throughout the year and over decades, these forts repeatedly drew a range of Native leaders, families, and warriors to the same places. This meant that when tensions escalated into violence, they often coalesced outside fort walls on the same Native lands time and again. Fortunately for Makahs, no forts were located at Cape Flattery, so they did not suffer from this violence at home. Instead, they found themselves in conflict with neighboring groups often on the lands of another people with whom they were not at war.

Company officials lacked the power to control intertribal conflicts for most of the first half of the nineteenth century, so no consistent policy with respect to this type of violence emerged. At times they desired to curb indigenous violence in order to create a safe and ordered environment for profitable exchanges. From the perspective of Chief Trader James McMillan at Fort Langley in 1828, violence among Indians was not the problem; instead, it was that conflict hampered Native abilities to collect furs. He wrote, “The poor tribes of this quarter Cannot attend to any thing like hunting [for furs] while their Powerful Neighbours from Van[couver] Island are allowed to Murder and Pillage them at pleasure.”36 McMillan believed that the commercial existence of the fort required order and safety. But company officials ignored intertribal violence when it did not inhibit trade. At least one official, Roderick Finlayson, even promoted conflict among communities, noting years later, “The policy of the Company was honesty—and also to keep the several tribes divided and at enmity among themselves. This plan followed for purposes of protection to ourselves—in short to keep up a jealous feeling between the respective tribes.”37 In charge of Fort Victoria from 1844 to 1849, Finlayson ignored the murder of Chief George, a Makah titleholder, just outside Fort Victoria in 1846. Visiting from the Columbia River, several Chinooks murdered the Makah chief after watching him exchange a sea otter skin for trade goods from Finlayson. While robbery might have partly motivated the killers, the reasons for attacking him were probably more complex. One British observer noted, “[George] had doubtless in his time played many tricks of the same kind as that to which he now fell a victim; they usually act and react one upon the other.”38 Although this comment is steeped in white assumptions of vengeful Natives, it speaks to the underlying reality that complex indigenous reasons—probably a combination of economic competition and a protest against Makah control of regional trade networks, in this case—provided the motivations for violence.

At other times, however, intertribal conflict made Finlayson anxious. During the fall of 1846, S’Klallams took possession of a drift whale Makahs had harpooned but lost. When the People of the Cape demanded a share of the whale and, more important, the return of their whaling gear, S’Klallams refused. This resulted in a “great battle” between the two peoples, and the S’Klallams “had suffered very severely.” S’Klallams retaliated by killing Chief Yela ub’s brother and some of his people when the Makah traders were paddling home after visiting Fort Victoria. Yela

ub’s brother and some of his people when the Makah traders were paddling home after visiting Fort Victoria. Yela ub set out in twelve canoes with more than one hundred warriors and attacked a S’Klallam village. He took eighteen slaves and the heads of eight warriors that he “stuck on poles placed in the bows of the canoes[…,] carried to their village and placed in front of the lodge of the warriors who had killed them.”39 A year later, the tensions between the two peoples still simmered and concerned those living at Fort Victoria. In 1848, Captain George Courtenay soothed Finlayson’s anxiety by bringing the fifty-gun HMS Constance into Victoria Harbor to defuse a Makah-S’Klallam conflict unfolding just outside the fort’s gate.40 This incident reflected the Hudson’s Bay Company’s minimal ability to control indigenous peoples in the spaces beyond the walls of forts.

ub set out in twelve canoes with more than one hundred warriors and attacked a S’Klallam village. He took eighteen slaves and the heads of eight warriors that he “stuck on poles placed in the bows of the canoes[…,] carried to their village and placed in front of the lodge of the warriors who had killed them.”39 A year later, the tensions between the two peoples still simmered and concerned those living at Fort Victoria. In 1848, Captain George Courtenay soothed Finlayson’s anxiety by bringing the fifty-gun HMS Constance into Victoria Harbor to defuse a Makah-S’Klallam conflict unfolding just outside the fort’s gate.40 This incident reflected the Hudson’s Bay Company’s minimal ability to control indigenous peoples in the spaces beyond the walls of forts.

The company did use its limited power to exercise retributive violence against Indians for perceived depredations on non-Natives and their property. This ad hoc policy established a racialized precedent that haunted the ča·di· borderland for decades. In January 1828, S’Klallams killed HBC employee Alexander McKenzie and his companions along Hood Canal. As with many interracial acts of violence in this borderland, the S’Klallams had numerous reasons for attacking the HBC party. An experienced fur trader, McKenzie had married the “Princess of Wales,” the daughter of Concomly, the powerful Chinook chief who kept slaves, including several S’Klallams. McKenzie’s wife accompanied the party, and S’Klallams took her hostage, perhaps to bargain for their people’s freedom from Concomly. S’Klallams were also upset that the company traded with their longtime borderlands enemies, the Cowichans of Vancouver Island. S’Klallam chiefs had made several efforts to dissuade McKenzie and others from trading with Cowichans. Adding insult to injury, the company had established Fort Langley north of S’Klallam space. This benefited indigenous rivals and prevented S’Klallam chiefs from serving as intermediaries. Last, indigenous oral accounts point to earlier injustices traders had committed against these people: McKenzie’s party could have been killed in retaliation.41

Chief Factor John McLoughlin decided that the Hudson’s Bay Company needed to employ a policy of retributive violence against Indians who murdered company employees. Writing from Fort Vancouver to his superiors in London about the killing of McKenzie, McLoughlin argued, “To pass over such an outrage would lower us in the opinion of the Indians, induce them to act in the same way, and when an opportunity afforded kill any of our people, and when it is considered the Natives are at least an hundred Men to one of us it will be conceived how absolutely necessary it is for our personal security that we should be respected by them, & nothing could make us more contemptible in their eyes than allowing such a cold-blooded assassination of our People to pass unpunished & every one acquainted with the character of the Indians of the North West Coast will allow they can only be restrained from committing acts of atrocity & violence by the dread of retaliation.” He believed that conditions unique to the Northwest Coast at this time—Indians outnumbered whites, these Natives only respected vengeance—necessitated a violent response.42

Although the punitive expedition targeted ethnic S’Klallams rather than all Indians in general, this action illustrated an early example of the racialized nature of colonial power that whites used to control indigenous peoples, something that officials noted at the time. Led by Chief Trader Alexander McLeod, a force of about sixty men left Fort Vancouver in June, entered Puget Sound from the south, and set out in canoes for S’Klallam villages. McLoughlin instructed McLeod to find the “murderous tribe, and if possible, to make a salutary example of them, that the honour of the whites was at stake.” On the way to rendezvous with the HBC schooner Cadborough, McLeod’s party encountered two S’Klallam lodges. They fired on those sleeping inside, killing at least two families. After meeting up with the Cadborough, the expedition set out for the distant S’Klallam village at New Dungeness on the south side of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Under cover of fire from the schooner, the expedition’s forces landed. After recovering the Princess of Wales and some articles from McKenzie’s party, they looted what provisions and whale oil they could carry. Then they burned the village and destroyed the rest of the S’Klallams’ property, including nearly thirty canoes, while the inhabitants watched from the forest’s safety. Although critical of McLeod’s leadership, Frank Ermatinger, an HBC clerk accompanying the expedition, reported that the extensive destruction of property would “be seriously felt for some time to come.”43 He believed that news of this retribution would travel among regional Indians. Makah chiefs certainly heard of this incident, and this story of HBC vengeance likely made the rounds among Indians such as young Yela ub, then working at Fort Langley. A year later, McLoughlin exacted a similar punishment on Clatsops for pillaging the wreck of the company’s William and Ann at the mouth of the Columbia River.44 Together, these responses illustrated the desire of some HBC officials to use collective violence when they could in order to punish Indians for perceived wrongs.

ub, then working at Fort Langley. A year later, McLoughlin exacted a similar punishment on Clatsops for pillaging the wreck of the company’s William and Ann at the mouth of the Columbia River.44 Together, these responses illustrated the desire of some HBC officials to use collective violence when they could in order to punish Indians for perceived wrongs.

During the 1830s and 1840s, Makahs and others challenged HBC efforts at controlling Indians. One area of contention involved Northwest Coast slavery, specifically the enslavement of non-Natives by indigenous peoples. Company employees found it necessary to adhere to indigenous protocols when redeeming slaves from Makah leaders. During the winter of 1833, a storm drove a “junk” laden with rice and fourteen sailors out of sight of the Japanese coast. They drifted east across the Pacific for three months and came within sight of Cape Flattery. Makahs paddled out to the vessel and found a man and two teenage boys who had survived on rice and freshwater collected from rain. After enslaving the Japanese survivors, Makahs seized the vessel and its goods and broke it apart to salvage the useful materials. Chinook Indians brought the news of the unusual slaves to McLoughlin at Fort Vancouver; although he wanted to free the captives as soon as possible, he could not address the issue until later that year. Captain William McNeill, master of the HBC brig Llama, redeemed the captives by purchasing them from Chief George, the same chief whom Chinooks murdered a decade later outside Fort Victoria. After spending several months at Fort Vancouver waiting for a ship, the Japanese survivors caught one headed to London; from there the survivors attempted to return to Japan. Diplomatic tensions between the United Kingdom and Japan, in addition to the Japanese attitude that regarded anyone who left the country—even accidentally—as contaminated, prevented them from returning home.45 In the mid-1840s, the Hudson’s Bay Company also redeemed a white sailor whom Chief George had enslaved; much to the consternation of other whites, this sailor voluntarily returned to Chief George after his release. Stories of powerful Makah chiefs who kept non-Native slaves continued to color white opinions of the People of the Cape throughout the mid-nineteenth century.46 These incidents demonstrated that Makahs had the ability to control space on their terms. King George men could not enter Makah villages and simply demand the release of non-Native slaves—they had to accede to indigenous protocols and purchase them from the owner.

Even in spaces closer to forts, the Hudson’s Bay Company had only slightly more ability to punish Indians for perceived depredations, especially theft. At Fort Victoria, some Makahs ran afoul of the company’s efforts to control Natives and protect HBC property. In 1847, an HBC employee whipped a Makah man caught breaking into one of the outpost’s warehouses; when “a body of Cape Flattery Indians … threatened to attack the Post in retaliation,” Lekwungen warriors took up arms to protect the fort, Douglas noted to his superiors. But the theft of company livestock vexed Douglas more. In 1848, he complained of this “mischievious practice which must be checked by the punishment of the Offender, an object in which we have partly succeeded.” By 1850, “wandering Tribes” became such a problem that he appointed four guards to stand permanent watch over company livestock. Although he did not name the “wandering Tribes,” Makahs frequented the lands around the fort and were likely part of this group.47

A range of experiences during the decades of the land-based fur trade shaped  isi·t’s and Yela

isi·t’s and Yela ub’s strategies for interacting with the growing presence of King George men and Bostons in the ča·di· borderland. They learned about the many ways they could use trade and new labor opportunities to the advantage of themselves and their people. But Makahs also participated in, witnessed, or heard about the kinds of violence that these opportunities drew, especially when the outsiders established permanent operations in Native homelands. So when non-Natives intruded on Makah spaces, the People of the Cape responded aggressively.

ub’s strategies for interacting with the growing presence of King George men and Bostons in the ča·di· borderland. They learned about the many ways they could use trade and new labor opportunities to the advantage of themselves and their people. But Makahs also participated in, witnessed, or heard about the kinds of violence that these opportunities drew, especially when the outsiders established permanent operations in Native homelands. So when non-Natives intruded on Makah spaces, the People of the Cape responded aggressively.

SETTLERS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES, 1845–1855

British and American settlers began arriving during the 1840s, thereby challenging indigenous sovereignty while providing more opportunities for Natives to engage the expanding settler-colonial world. The newcomers no longer simply needed small islands of security and order—forts—within an indigenous world; by the mid-nineteenth century, they required larger spaces of safety and order for pioneer enterprises, such as lumbering, farming, mining, and settling. This brought the newcomers into conflict with indigenous peoples, especially those living in places where outsiders wanted to build sawmills, open mines, and establish farms and towns. In order to ensure the newcomers’ safety, US and British officials drew from HBC strategies to attempt to control Indians.48 As in previous encounters, early settler-colonial processes depended on the participation and support of Native peoples. Without the labor provided by Natives who cut down trees, cleared land, tended livestock, and dug up coal, many early ventures would have failed. Northwest Coast peoples provided fish, potatoes, berries, and sea mammal oil to nascent settlements, critical commodities that sustained many of the first settlers who arrived in the mid-nineteenth century. More important, Native leaders interacted with settlers and colonial officials in order to strengthen their own authority over rivals and neighboring peoples.

During the mid-nineteenth century, the US and British empires began carving up the ča·di· borderland into supposedly discrete colonial spaces, yet these changes did not affect indigenous polities immediately. Coming along the Oregon Trail, increasing numbers of American filibusters settled south of the Columbia River. Supported by politicians with dreams of a continental nation, these newcomers agitated for US control over the entire Oregon Country. During the 1844 presidential contest, the Democratic Party embraced expansionist ideology and campaigned on the slogan “Fifty-Four Forty or Fight!” Once elected, President James K. Polk—who had never taken the slogan very seriously—abandoned the assertion that the western US boundary should extend north to the Russian frontier. Compromising instead on the forty-ninth parallel, his administration settled the boundary issue in 1846 through the Oregon Treaty. This ended nearly three decades of joint occupation in the Pacific Northwest and placed the boundary between US and British claims in the Far North American West “along the said 49th parallel of north latitude to the middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver’s Island, and thence southerly through the middle of the said channel, and of Fuca’s Straits, to the Pacific Ocean.” In 1848, the US Congress created the Oregon Territory, comprising the current states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho. A year later, Britain created the Colony of Vancouver Island. In 1853, Congress separated Washington Territory from Oregon Territory; six years later, Oregon became the thirty-third state in the union.49

Although the Oregon Treaty had defined the border between colonial claims, government officials quickly discovered what the People of the Cape and other borderlanders already knew—by nature, the marine portion of the boundary along the Strait of Juan de Fuca was permeable. Makahs probably learned of the new boundary quickly. If crewmembers of HMS Herald neglected to tell them when visiting Cape Flattery in 1846 while surveying the marine borderline, then HBC officials at Fort Victoria would have informed Makah visitors and traders. Throughout most of the 1850s, the Hudson’s Bay Company remained the Makahs’ top trading partner, with company vessels stopping at Neah Bay and the People of the Cape traveling to Victoria. Indiscriminate trade between Makahs and the company concerned US officials. George Gibbs, a member of the Pacific Railroad Exploration and Survey of 1852, noted that it was impossible to “check this traffic,” and he advised Congress that “in any treaties made with them, it should enter as a stipulation that they should confine their trade to the American side.” In 1858 an Indian agent surveying the region complained that “all the money paid out by [our] government and citizens [to the Makah] goes immediately over to Victoria to be invested in blankets, muskets, etc.” Both US and British officials complained of citizens from the other side crossing the border to sell liquor to Indians, “an evil which endangers the peace of the frontiers.” One Puget Sound Indian agent, G. A. Paige, noted in 1857 the impossibility of controlling this traffic because of the many small trading vessels plying local waters. Like those living in other borderlands in North America, local residents—both Native and non-Native—exploited the boundary for their own economic advantage.50

At this time, mobile Indians who ignored the border were part of a larger colonial concern about local borderlanders who disrespected official boundaries. For much of the mid-nineteenth century, the British worried about American squatters. Despite the demarcation of the boundary line in 1846, the potential for squatters north of the borderline concerned colonial and company officials. In response—and to support their economic diversification efforts—the Hudson’s Bay Company decided to encourage British emigration to Vancouver Island. Based on information provided by Douglas, the company believed that the island would be an ideal place for a colony because it offered cultivable lands in the south, sheltered harbors for a naval depot, and abundant timber and coal. Sir John Pelly, HBC governor, secured permission from the British crown to allow the company to establish a colony on Vancouver Island in 1849. The first settlers arrived by the barque Harpooner on May 31, 1849, and included coalminers, workmen, carpenters, bakers, a shipwright, and their families. These would have been the first settlers to interact regularly with the People of the Cape.51

The experience of Walter Colquhoun Grant, the first non-Native to settle independently of the Hudson’s Bay Company on Vancouver Island, illustrates that early emigrants needed assistance from both local Indians and company officials. A Scottish native, Grant arrived on Vancouver Island in the fall of 1849. He planned to manufacture prefabricated house frames to sell in California for $250 each. From the beginning, his venture encountered difficulties. Concerned about Grant’s “destitute means”—he came with no money—the company paid for his passage from California to Fort Vancouver, gave him company credit, and provided him with livestock. The men Grant hired for this venture arrived at Fort Victoria two months before him, and Douglas had trouble preventing them from leaving for more lucrative work on American vessels or for the California gold fields. When Grant arrived, Douglas took him along the coast to point out potential sites for his sawmill and to introduce him to local Indians. Against Douglas’s recommendation, Grant chose a location twenty-five miles from Fort Victoria because it offered an abundant supply of timber and a stream for his sawmill. Douglas “endeavoured strongly to impress on the minds of Captain Grant and his followers, the invaluable importance, both as regards the future well being of the Colony, and their own individual interests, of cultivating the friendship of these Children of the forest.” The experienced fur trader worried that settlers such as Grant would antagonize local Indians.52

But Natives and settlers had many motivations for interacting in productive ways. Grant relied on indigenous labor and information. While at Neah Bay during a survey of the region, he asked Chief Yela ub for advice on where to settle and locate his sawmill. Already exhibiting a proclivity to direct settlers away from Makah space, Yela

ub for advice on where to settle and locate his sawmill. Already exhibiting a proclivity to direct settlers away from Makah space, Yela ub told him about large tracts of arable land and timber resources across the strait on Vancouver Island.53 Men from nearby Nuu-chah-nulth villages helped in felling trees and building Grant’s sawmill, which he had located on indigenous land. Like those living near Fort Victoria, Grant and his men bought salmon and potatoes from their indigenous neighbors. Many Native borderlanders welcomed the new markets in commodities and labor that settlers provided. Others, however, worried about newcomers taking land and resources, and resistant Indians stole from and threatened the outsiders. Echoing the complaints of other settlers, Grant accused Indians of “depredations”—the contemporary term for theft—and claimed that they caused everything to go “to ruin” during his absences.54 As interracial tensions mounted, colonial officials on both sides of the new boundary became concerned.

ub told him about large tracts of arable land and timber resources across the strait on Vancouver Island.53 Men from nearby Nuu-chah-nulth villages helped in felling trees and building Grant’s sawmill, which he had located on indigenous land. Like those living near Fort Victoria, Grant and his men bought salmon and potatoes from their indigenous neighbors. Many Native borderlanders welcomed the new markets in commodities and labor that settlers provided. Others, however, worried about newcomers taking land and resources, and resistant Indians stole from and threatened the outsiders. Echoing the complaints of other settlers, Grant accused Indians of “depredations”—the contemporary term for theft—and claimed that they caused everything to go “to ruin” during his absences.54 As interracial tensions mounted, colonial officials on both sides of the new boundary became concerned.

Those governing the Colony of Vancouver Island worried that the presence of British settlers made it all the more important to control Indians. After founding the colony in 1849, the Hudson’s Bay Company intensified its policy of inflicting devastating retribution for violence against whites and their property. Unlike previous attempts to develop a coherent policy, these efforts worked because official colonization brought with it the military backing of the British crown. On the Northwest Coast, this power manifested itself in the gunboats (sloops-of-war, corvettes, and frigates) of the Royal Navy, which local officials deployed against Indians. The resultant gunboat diplomacy approved by Douglas left “the smouldering ruins of a village and a scattered village tribe” as “the telling testaments of the process of keeping Northwest Coast Indians ‘in awe of British power.’ ”55 These destructive expeditions illustrated the growing colonial ability to project power into indigenous spaces.

The People of the Cape kept a wary eye on the Royal Navy vessels sailing—then steaming—through local waters to shell other villages. During 1850 and 1851, the fledgling colonial government at Victoria found itself needing to respond in kind to the murder of three deserters from the company ship Norman Morison. Believing that the Newitty (Tlatlasikwala Kwakwaka’wakws) near Fort Rupert on the northern edge of Vancouver Island had murdered the deserters, colonial officials called on the Royal Navy’s corvette Daedalus to punish the offenders. Echoing sentiments expressed by HBC officials in previous decades, they believed that “if we make no demonstration the Indians will lose all respect for us and may make an attack on [Fort Rupert].” As in the earlier incidents against the S’Klallams and Clatsops, the British burned longhouses and canoes at Nahwitti village, deciding that if the community would not surrender the murderers, then the whole group deserved punishment. The Newitty sued for peace on their own terms by bringing three mangled Indian bodies to Fort Rupert, telling the British that these were the offenders.56 Colonial officials felt that they had accomplished their goals. Douglas reported to William Tolmie at Fort Nisqually, “The Indians [are] all quiet and civil, being greatly awed by the example made of the Neweetees.”57 In what would become a pattern for Douglas, however, he ignored the way in which the Newitty chiefs confronted British retributive violence. Newitty actions demonstrated that Native leaders still had enough power to control some outcomes of conflicts within indigenous spaces. Native chiefs, not British officials or soldiers, executed the offenders.

Less than six months later, at the beginning of 1852, British colonial officials again faced Natives—this time Makahs and their aggressive salvaging and burning of the Una—exercising sovereignty over indigenous spaces. The way colonial officials responded reveals the limitations of colonial power while highlighting the emerging racial divide in the region. When initially reporting on the brig’s loss and Makah actions, Douglas highlighted the fledgling colony’s inability to protect British lives and property: “The Natives … gathered about the wreck in vast numbers, and behaved with great barbarity towards such of the ‘Una’s’ crew as were landed from the wreck. They broke open and rifled the Seamens’ chests, stript them of their clothes, and maltreated those who attempted, unarmed as they were to defend their property.” In fact, only the intervention of the Americans—fellow whites—prevented “greater atrocities” from happening and kept the valuable furs and gold out of Makah hands.58 Incidents such as this supported his argument that the colony needed even more naval support to protect it.

Most especially, though, the incident frustrated Douglas because there was little he could do immediately about this affront to British authority and property. For one, he did not have ready access to a company vessel that he could use to punish Makahs. The Cadborough was on a trading voyage in the north, while US customs officials in Olympia detained another two—the brigantine Mary Dare and steamer Beaver—for alleged duties violations. It was not until the end of January that he could deploy the Cadborough and “a well appointed force” to Neah Bay to bring the Indians “to a serious account for their barbarous conduct on that occasion, in order to repress the mischievous consequences likely to arise from their evil example, and deter other Savage Nations from committing wanton outrages on the persons and property of Her Majesty’s subjects.” Seeming more appropriate for a purposeful attack on the Una than a vigorous salvaging of a shipwreck, Douglas’s rhetoric indicated the mounting pressures he felt at securing white property against aggressive and still powerful Indians. Second, he could not ignore the fact that Neah Bay was in US territory. Unlike dealing with Native peoples north of the border, he could not simply shell this village of American Indians as he had responded to the Newitty. Instead, he was careful to inform Edmund A. Starling, the federal Indian agent for the Puget Sound District in Oregon Territory, of his actions against the Makahs.59

When reporting back to his superiors in both the colonial and company offices, Governor Douglas downplayed the fact that a Makah chief had handled the threat of British violence in his own manner. The governor condemned the chief’s “barbarous actions” of the summary execution of ten Makahs and the immolation of another while reassuring his superiors that deploying gunboat diplomacy—even without the firing of any shots—had achieved a suitable result. He explained that this expedition “produced the desired effect of alarming the Natives” and “has made a deep impression in the minds of the Natives, who were intently watching our proceedings.”60 Douglas’s threat of gunboat diplomacy reflected Lord Palmerston’s mandate from several years earlier: “Wherever British subjects are placed in danger … thither a British ship of war ought to be … for the protection of British interests.” But it also exemplified an even longer HBC effort of “keeping the Indians in awe” of British power in the Pacific Northwest.61 Although he framed the outcome of this incident as a success of personal, HBC, and colonial policies, the governor appeared too embarrassed to admit that Cape Flattery was still Makah space under the sovereign power of influential chiefs. Neither the British nor the Americans were in control—the People of the Cape were. For the time being, Douglas had to acquiesce to Makah authority because HBC operations in this region still depended on the consent and support of local chiefs.