One winter morning in 1855, Makahs at Neah Bay village awoke to find a vessel anchored in the shelter of the bay. They recognized the schooner Potter and knew its captain, E. M. Fowler. During the past several years, Fowler had visited Neah Bay to trade, and, ominously, his Cynosure had brought smallpox to the Makahs in 1853. As on its previous visit, the Potter brought some Bostons (Americans) on government business. Earlier, Colonel Michael Simmons, the territorial Indian agent, had stopped at Neah Bay and tried to impress upon the People of the Cape the importance of signing a treaty with the United States.1 This time the Potter carried Washington’s territorial governor Isaac Stevens and members of his treaty commission, including Simmons, Benjamin F. Shaw (interpreter), and George Gibbs (surveyor and secretary). Stevens believed that he had tapped the best talent in the territory for his commission. “Old frontiersmen” and some of the earliest settlers to the region, Simmons had been described by his admirers as the “Daniel Boone of Washington Territory,” while Shaw was a noted translator of Chinook jargon, the local trade language. Gibbs had also lived in the area for some time, coming west after studying law at Harvard and working for the American Ethnological Society in New York.2 The commissioners had come to this remote corner of the United States to negotiate a treaty with the residents of Cape Flattery.

After warily observing the governor and surveyor map out reservation boundaries, six leaders from Neah Bay and other nearby Makah villages boarded the Potter to learn about the proposed treaty and to state their concerns. With the help of Captain Jack—a neighboring S’Klallam chief who translated from Chinook jargon, a language spoken by Captain Fowler and Shaw, into Makah—the chiefs listened while Stevens explained that the Great Father had sent him to watch over them. To open the negotiations, Governor Stevens explained his perspective on the proposed treaty. Like the treaties Stevens had signed with Puget Sound tribal nations, this one would transfer Native land to the United States. In return, the federal government would provide a reservation, school, farms, and a physician, among other items.3

The chiefs cared little for what Stevens offered. Instead, each one emphasized the importance of retaining their marine tenure. Five of them spoke about the need to reserve their fishing and whaling rights.  alču·t (“kuhl-choot”), one of the two chiefs representing Neah Bay, stated, “I ought to have the right to fish, and take whales and get food when I like. I am afraid that if I cannot take halibut where I want, I will become poor.” Governor Stevens acknowledged this position by replying that he wanted them to continue fishing and whaling; he only wanted whites to do so, too.

alču·t (“kuhl-choot”), one of the two chiefs representing Neah Bay, stated, “I ought to have the right to fish, and take whales and get food when I like. I am afraid that if I cannot take halibut where I want, I will become poor.” Governor Stevens acknowledged this position by replying that he wanted them to continue fishing and whaling; he only wanted whites to do so, too.  alču·t conceded that he “would live as a friend to the Whites and they should fish together.” Except for the 1853 smallpox epidemic, the past several decades of interactions with King George men (British) and Bostons had gone well because the People of the Cape had profited by selling oil, sealskins, and fish to traders and vessels.

alču·t conceded that he “would live as a friend to the Whites and they should fish together.” Except for the 1853 smallpox epidemic, the past several decades of interactions with King George men (British) and Bostons had gone well because the People of the Cape had profited by selling oil, sealskins, and fish to traders and vessels.

Bi id

id a (“bih-ih-duh”) Village, 1862. Neah Bay lies beyond Bi

a (“bih-ih-duh”) Village, 1862. Neah Bay lies beyond Bi id

id a, and the cedar longhouses of Neah Bay village can be seen on the far shore. Watercolor by James Swan, from the Franz R. and Kathryn M. Stenzel Collection of Western American Art. Image supplied courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

a, and the cedar longhouses of Neah Bay village can be seen on the far shore. Watercolor by James Swan, from the Franz R. and Kathryn M. Stenzel Collection of Western American Art. Image supplied courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

But Makah statements also articulated a marine space connection broader than fishing and whaling rights. Individuals spoke of specific marine locations they owned.  a·baksa

a·baksa (“kuh-buhk-saht”) from

(“kuh-buhk-saht”) from  u·yas (“tsoo-yuhs”), a coastal village at the mouth of the Sooes River, spoke of an estuary as his property.

u·yas (“tsoo-yuhs”), a coastal village at the mouth of the Sooes River, spoke of an estuary as his property.  i·čuk (“kee-chook”) of Tatoosh Island explained that his holdings encompassed the island and extended through marine waters to the Hoko River’s mouth, about fifteen miles away. More important, these Makah leaders identified the ocean as the homeland of their people. In describing his holdings,

i·čuk (“kee-chook”) of Tatoosh Island explained that his holdings encompassed the island and extended through marine waters to the Hoko River’s mouth, about fifteen miles away. More important, these Makah leaders identified the ocean as the homeland of their people. In describing his holdings,  i·čuk told the Bostons that “he did not want to leave the saltwater.” Another chief,

i·čuk told the Bostons that “he did not want to leave the saltwater.” Another chief,  it

it a·ndaha· (“iht-ahn-duh-hah”), echoed his words, repeating that he, too, did not wish to leave the saltwater. Appointed “head chief” by Governor Stevens,

a·ndaha· (“iht-ahn-duh-hah”), echoed his words, repeating that he, too, did not wish to leave the saltwater. Appointed “head chief” by Governor Stevens,  aq

aq ·wi

·wi (“tsuh-kah-wihtl”) of Ozette stated it clearest: “I want the sea. That is my country.” Wanting to impress upon the governor the importance of this statement,

(“tsuh-kah-wihtl”) of Ozette stated it clearest: “I want the sea. That is my country.” Wanting to impress upon the governor the importance of this statement,  aq

aq ·wi

·wi refused to even consider the terms of the treaty until Stevens joined him in a canoe on the saltwater. As the two leaders paddled around, the Ozette chief explained that the sea was his country. Although it is tempting to imagine this exchange as literally one where the two men were alone in a small canoe on the water, Captain Jack and Fowler probably accompanied them to help Stevens understand

refused to even consider the terms of the treaty until Stevens joined him in a canoe on the saltwater. As the two leaders paddled around, the Ozette chief explained that the sea was his country. Although it is tempting to imagine this exchange as literally one where the two men were alone in a small canoe on the water, Captain Jack and Fowler probably accompanied them to help Stevens understand  aq

aq ·wi

·wi .4

.4

Representing their people, forty-two Makahs signed the treaty by marking an “X” next to the approximations of their names that Gibbs noted. As their ancestors had done for generations, Makah chiefs protected their marine tenure and reserved their rights to the waters they claimed. Specifically, they secured their continued rights to fish and hunt whales and seals. This time, however, they used a non-Makah tool of diplomacy—a treaty—instead of indigenous protocols. From the perspective of the People of the Cape, Governor Stevens appeared to understand and acknowledge their tenure claims to customary marine space. They would not have signed the treaty otherwise.

The historical context of local power dynamics in the mid-nineteenth-century ča·di· borderland shaped the treaty negotiations between Bostons and the People of the Cape. At this time, the Makah held a better negotiating position than other American Indians west of the Cascade Mountains in Washington Territory, despite the recent mortalities from diseases that had burned through their communities. Not only were Makahs an important part of the settler-colonial economy, but whites still feared and respected them. Governor Stevens recognized that this tribal nation retained enough power to complicate the new territory’s development. Most important, though, Makah chiefs—the ones newly elevated to their positions due to the deaths of more experienced leaders—used the treaty to protect what was important to their people: the sea. Their ability to force Stevens to negotiate was significant because the governor appeared unwilling to do so with other tribal nations, even when it resulted in failed negotiations. Stevens’s negotiations south of Cape Flattery with the Quinaults, Queets, Satsops, Chehalis, Chinooks, and Cowlitz unraveled when he refused to grant them all their own separate reservations.5

The Makahs’ connection to the ocean and its resources shaped the concerns the chiefs expressed during the treaty negotiations. By describing the sea as his country,  aq

aq ·wi

·wi articulated cultural values central to his people’s relationship to customary marine space. First, his words reveal that the People of the Cape owned specific marine waters and resources. This contradicts the assumption underlying most narratives about settler-colonial expansion into indigenous spaces, namely the idea that property-oriented societies claimed lands and resources that Natives held in common and did not fully use. Second, the Ozette chief’s words and those of his peers also invoked the ways that Makahs made the sea their country through customary practices, such as whaling, sealing, and fishing. These practices enabled Makahs to exploit marine resources, which provided them with the wealth and power that better positioned them when they needed to negotiate with non-Natives.

articulated cultural values central to his people’s relationship to customary marine space. First, his words reveal that the People of the Cape owned specific marine waters and resources. This contradicts the assumption underlying most narratives about settler-colonial expansion into indigenous spaces, namely the idea that property-oriented societies claimed lands and resources that Natives held in common and did not fully use. Second, the Ozette chief’s words and those of his peers also invoked the ways that Makahs made the sea their country through customary practices, such as whaling, sealing, and fishing. These practices enabled Makahs to exploit marine resources, which provided them with the wealth and power that better positioned them when they needed to negotiate with non-Natives.

Captured by calling the sea their country, the Makahs’ worldview highlights how they conceptualized marine space differently from whites. Shaped by a common European geographical conceptualization that divided water from land, British and US officials in 1846 had used the Strait of Juan de Fuca, which separates Vancouver Island from the Olympic Peninsula, to make a convenient and natural boundary between colonial claims in the Oregon Country. When Governor Stevens and his treaty commission drew up the boundaries of the Makah reservation, they assumed that the coastline made a natural boundary to the north and west, like some invisible fence that would keep Makahs inside and other Indians and non-Native settlers outside. However, those on either side of the international border frustrated both British and US colonial officials who desired to keep Natives in their respective political, social, and economic places.

Unlike Europeans and Euro-Americans who saw marine water as a boundary separating one colonial space from another, Makahs and other indigenous borderlanders continued to experience these waters as a space of connections. Preexisting indigenous networks of trade, kinship, and violence endured. The continuation of these networks confounded the efforts of officials on both sides of the border to create a more traditional boundary line between nation-states. By engaging in regional indigenous networks, peoples such as Makahs and neighboring Nuu-chah-nulths illustrate that characteristics and processes of the ča·di· borderland endured throughout the nineteenth century. The indigenous borderlands persisted not only into the period when a separate but related colonial borderland emerged but also after 1846, when Britain and the United States established what they considered a definitive boundary between their respective claims. The continuation of ča·di· borderland dynamics shaped the development of Washington Territory and the British colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia to the north.6 These borderland characteristics also enabled Makahs to resist the growing power of the United States even as they continued to engage with settler-colonialism to benefit their people.

LOCAL POWER AND NEGOTIATING THE TREATY OF NEAH BAY, 1855

The ability to exploit lucrative marine resources left the People of the Cape in a better position than other American Indians when negotiating with the United States. Because the US treaty negotiators valued Makah contributions to the nascent settler-colonial economy, Governor Stevens was willing to negotiate a few key points in the Treaty of Neah Bay. As they had been for decades, the Makah were the most feared tribal nation west of the Cascades in the new territory, and officials worried that this group could cause them trouble, even after having lost three-quarters of their people to Eurasian diseases. In North America “every land transfer of any form included elements of law and elements of power.”7 When examining treaty making, land sales, and theft of indigenous spaces, most scholars have limited their scope to explaining that settler-colonial societies possessed more power than indigenous peoples. Looking back in time with a wide-angle lens, we can see that US treaty negotiators in Washington Territory acted from a “position of assured dominance,” believing that they possessed more power than Indian tribes in the mid-nineteenth century.8 For instance, the population of the United States outnumbered American Indians in the territory; an entire legal framework of treaties, laws, and courts supported the taking of Indian land and control of Natives; and the nation could deploy its military might against tribal nations. Without denying these facts, however, we should consider local dynamics of indigenous power that shaped specific negotiations, such as the Treaty of Neah Bay. Due to the aggressive actions of the People of the Cape and their leaders in the period before the treaty negotiations, Bostons and King George men continued to respect Makah power. So even within the framework of a process predisposed to work against indigenous peoples, Makah chiefs in 1855 had enough power to alter the treaty to protect what was most important to their people—continued access and rights to the sea and its resources upon which they had relied for generations.

At the time of the treaty negotiations, whites depended on the contributions the People of the Cape made to the settler-colonial economy. Makahs provided whale oil, fish, furs, information, and labor to the British colonies in the region and Washington Territory, a fact the treaty commissioners appreciated and respected. Having lived in Puget Sound for nine years before Stevens appointed him Indian agent in 1854 and to the treaty commission, Michael Simmons wrote in a local paper, “[The Makah] are altogether the most enterprising within the Territory. In industry, thrift, and enjoyment of the comforts of life they are not approached by any neighboring tribe southward. They take the whale with harpoon, spears, etc., of their own invention and venture in their whale excursions in their light canoes an almost incredible distance from land.” Other observers informed the governor that the Makah technique with indigenous equipment was “vastly superior” to American whaling methods, which lost many whales each voyage. George Gibbs, surveyor for the commission, understood the scale of contribution Makah whalers made to the settler-colonial economy—in the 1850s, he had reported to Congress that Makahs annually traded tens of thousands of gallons of oil.9 The fact that most of these anecdotal observations of Makah contributions to the settler-colonial economy were written after diseases had severely reduced the tribal nation seems to indicate that local whites still believed that the People of the Cape had an important economic role to play in the new territory.

Since the maritime fur trade, Makahs had participated in making colonialism possible in the Northwest Coast. A product harvested and processed into a vital commodity for both indigenous peoples and newcomers, whale oil was a key ingredient non-Natives used to expand colonial spaces in the region. Makah oil heated and lit homes and businesses in nearby towns such as Victoria and Port Townsend. Victorian era colonialists prided themselves in bringing light—a central component to imperial projects across the world—to the Pacific Northwest. Many Victorians believed that wherever the British flag flew, they had a “responsibility to import the light of civilization (identified as especially English), thus illuminating the supposedly dark places in the world.”10 Little did these Victorians expect, though, that indigenous oil would fuel English lamps. Large quantities of Makah oil also greased the skids of local logging operations. By removing trees, newcomers tamed an otherwise threatening wilderness by clearing the land for towns and farms. Proud of transforming wilderness spaces into civilized places, non-Natives ignored the irony that indigenous oil expedited the processes of settler-colonialism. Although this seemed lost on Stevens, Gibbs, and Simmons, these individuals knew and appreciated the products provided by the People of the Cape. These treaty negotiators expected to hear Makah statements that insisted on their continued rights to whale and fish in customary waters. During the negotiations, Stevens acknowledged Makahs’ contributions to settler-colonialism when he told the chiefs, “I know what great whalers you are,” and when he promised that “[the Great Father] will send you barrels in which to put your oil, kettles to try it out, lines and implements to fish with.”11 But the federal government never kept these promises after local officials gained enough power to ignore Makah demands later in the nineteenth century.

Acknowledgment of the ways American Indians supported settlers provided a problematic tension in the treaty process advocated by the federal government and territorial officials. During the third quarter of the nineteenth century, whites possessed a “deep ambivalence about the place of Indians in urban life.”12 But settlers living outside urban spaces felt this ambivalence, too. Non-Natives wanted to continue benefiting from indigenous products, trade, and labor. Local Indians, and even those from as far north as Alaska, provided a wealth of goods that fed early settlers and fueled commercial enterprises. Native men, women, and children cleared forests and broke ground; harvested crops; delivered mail, cargo, and people in their canoes; piloted non-Native vessels through unknown and dangerous waters; and provided companionship to white men far from home. Yet many newcomers desired to separate Indians from white society.

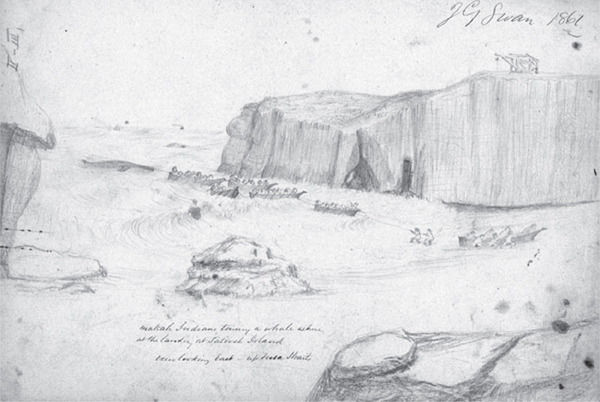

Makah Indians towing a whale ashore at the Tatoosh Island landing, 1861. Just as they did in 1999, the Makahs depicted in this sketch are pulling the whale onto the beach. Sketch by James Swan. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution [NAA INV 09037900].

The actions of territorial officials such as Governor Stevens and the treaty commissioners often reflected this ambivalence. Stevens believed that Washington Territory urgently needed Indian treaties, and he set out to put Natives in their place. By 1855, American settlers had already filed thousands of land claims under the Donation Land Act and the Preemption Act, which Congress had extended to Washington Territory the previous year. Often located on indigenous lands, these claims brought newcomers into conflict with local American Indians. In the winter of 1846, Indians shot and butchered a bull owned by an American settler who had taken up a claim near Fort Nisqually, and conflicts such as these became common when more outsiders arrived.13 Just before Congress created Washington Territory in 1853, separating it from the northern half of Oregon Territory, the number of whites killed by American Indians had increased from thirteen in 1850 to fifty-eight in 1852, including thirty-nine emigrants.14 Although many of these deaths occurred in areas south of the Columbia River, which separated Washington and Oregon territories, the statistics pointed to a disturbing regional trend of rising interracial conflict. Natives also complained of violent whites who failed to pay for work or services.15 These incidents weighed on the mind of the new governor.

A Jacksonian Democrat, West Point graduate, veteran of the Mexican War, and ardent expansionist, Isaac Stevens initially believed that he had the power and personal ability to impose the government’s reservation policy on Indians. Characterized as a “young man in a hurry,” Stevens felt pressured to negotiate treaties quickly to open the land for settlers, economic development, and roads. On February 28, 1854, in his address to the first session of the territorial legislature, the governor promised to take the “promptest action” at terminating Indian title to lands. He also hoped that peaceful settlement with tribal nations would enable white citizens and businesspeople in the territory to continue benefiting from the indigenous labor and goods critical to settler-colonial processes.16

One strain of Stevens’s ambivalence about the place of Indians in Washington Territory emerged from the federal government’s entwined reservation and treaty policies. George W. Manypenny, commissioner of Indian affairs, had committed his agency to a strategy of using treaties to assign tribal nations to small reservations where federal agents would work to “civilize” American Indians, training them to develop “such habits of industry and thrift as will enable them to sustain themselves.” Manypenny believed that this strategy was a viable alternative to extermination. Before beginning the territory’s treaty negotiations, Stevens met with Manypenny and the commissioner’s second-in-command, Charles Mix, in the nation’s capital. These officials directed the new territorial governor to concentrate Washington’s American Indians onto as few reservations as possible. Mix advised Stevens to minimize the number of treaties in the territory, encouraging him to unite bands into tribes and to concentrate multiple tribes onto each reservation. Manypenny and Mix were concerned about creating many small reservations because this strategy had caused the Senate to deny ratification of the nineteen earlier treaties Anson Dart (first superintendent of Indian affairs for Oregon) had negotiated with Indians in Oregon Territory in 1851. Agreeing with their recommendations, Stevens left Washington, DC, hoping to consolidate all the territory’s Natives onto two reservations, one west of the Cascades and another east of the mountains. He did not plan on making the same mistake Dart had made in giving each tribe its own reservation. Stevens assumed that this strategy would reduce administrative costs and curb “mischievous” Indian dispositions.17

To facilitate the process, Stevens adopted a treaty template that reflected the federal government’s philosophy and the policy advocated by the Office of Indian Affairs. Before treating with any of Washington’s tribal nations, he asked Gibbs to develop a uniform treaty that reflected local conditions and could be used with all groups. This template included a key provision protecting indigenous fishing at “usual and accustomed places” both on and off the reservations. The treaty commissioners believed that if they allowed tribal nations to continue normal subsistence practices, American Indians could support themselves, which would save the government money. Besides, Native fishing would not compete with settler-colonial land uses, such as farming, lumbering, mining, road building, and town establishment, the commissioners assumed. The fishing clause embodied the other strain of Stevens’s ambivalence over the place of Indians in the social and economic life of the territory. By protecting the right of tribal members to fish at “usual and accustomed places,” the treaties—documents designed to remove indigenous peoples from their lands and keep them separate from white spaces and society—encouraged Natives to leave the reservation in order to pursue customary practices that kept them engaged with Euro-Americans.18

The treaty commission then attempted to follow a reservation policy designed to draw lines around American Indians, removing them from territorial society to prepare them for eventual assimilation. Ardent supporters of this policy, Stevens and the commissioners assumed that physical reservation borders would contain Indians. In an 1858 annual report, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Mix explained the goal of the reservation policy to the secretary of the Interior, writing, “Great care should be taken in the selection of the reservations, so as to isolate the Indians for a time from contact and interference from the whites.” Also, “No white persons should be suffered to go upon the reservations.” And further, “There should be sufficient military force in the vicinity of the reservations to prevent the intrusion of improper persons upon them … and to aid in controlling the Indians and keeping them within the limits assigned to them.”19 When marking out the reservation at Cape Flattery, commissioners believed that borderlines drawn across the land and along the coast would keep Makahs in and non-Makahs—both Natives and non-Natives—out.

Territorial officials reinforced the physical reservation border with additional boundaries designed to keep Makahs and other Washington Natives in their place. Controlling American Indians lay at the heart of these efforts.20 Some officials, such as Governor Stevens, advocated military control over the territory’s indigenous peoples. A longtime supporter of using the military to monitor Natives in the frontier, Stevens tried and failed to get support for a strong territorial militia. Without this type of military power at his disposal, Stevens turned to the treaties to encode some method of control. Along with other territorial officials, Stevens wanted to control Indian trade, redirecting it to benefit US rather than British interests. Although the Hudson’s Bay Company went unnamed, article 13 of the Treaty of Neah Bay dealt implicitly with the company by prohibiting Makahs from trading “at Vancouver’s Island or elsewhere out of the dominions of the United States.” While foreclosing indigenous economies if enforced, this provision reflected Stevens’s desire to undermine the Hudson’s Bay Company’s influence over the territory’s Indians. In his instructions to the officers in charge of surveying the territory, Stevens wrote, “The Indians must look to us for protection and counsel…. I am determined, in my intercourse with the Indians, to break up the ascendency of the Hudson Bay Company and permit no authority or sanction to come between the Indians and the officers of this government.” The treaty provision prohibiting American Indians from trading outside the nation’s boundaries struck at the heart of ča·di· borderland dynamics that ignored nation-state boundaries yet echoed concerns expressed by Edmund Starling, an earlier Indian agent, who complained about Natives crossing the border to trade for blankets and other goods.21 As the colonial entities of Vancouver Island and Washington Territory took shape in the mid-nineteenth century, each set of officials worked to make this trade benefit their colony and not the other’s. Ironically, this treaty provision redirecting Indian trade toward Americans strengthened the connections between the territory’s indigenous peoples and non-Native society precisely when the federal government was attempting to separate the former from the latter through reservation policies. If enforced to the letter of the provision, the People of the Cape could no longer trade with their most important partners, the indigenous communities on Vancouver Island, instead needing to establish and enhance ties with newcomers living south of the strait.

The treaty commissioners also sought to control another troubling crossing of social boundaries, the captivity of non-Natives. Article 12 in the Treaty of Neah Bay ordered Makahs to free all slaves and not acquire any more. On the surface, this provision reflected national concerns over the expansion of slavery in the US West, and Congress had established Washington as an antislavery territory.22 Euro-Americans—especially those such as Stevens who had strong abolition backgrounds—characterized Northwest Coast Indian slavery as a backward institution that should be prohibited in the progressive territory.23 Even though the number of these incidents was small, white fears of Natives enslaving non-Natives underscored the importance of prohibiting slavery. In the decades before signing the Treaty of Neah Bay, Makahs had drawn the attention of HBC, British, and US officials intent on combating slavery because wealthy chiefs had purchased or captured Japanese, Russians, and white Americans, in addition to indigenous peoples from other communities. During the mid-nineteenth century, Neah Bay continued to be the center of the indigenous slave trade, and whites still feared becoming the property of Indians.24 Therefore, when the US treaty commission came to Neah Bay, prohibiting slavery—especially across racial lines—was a top priority. Yet in the decades after signing the treaty, federal agents at Neah Bay made few efforts at ending Makah slavery of Natives, thereby revealing that officials at the time only desired to prevent Indians from enslaving whites and other “civilized” peoples.25

The territorial legislature also used laws to erect legal boundaries controlling interracial relations. In 1854 and 1855, the legislature passed and amended a law voiding all solemnized marriages—unions officiated by clergymen or government officials—between whites and Indian men and women and making it illegal for anyone to solemnize such unions. During the land-based fur trade, interracial unions had been common.26 When settlers and colonial officials came to the region in the 1840s, they expressed their distaste for these relationships, especially when they resulted in mixed-race children. Berthold Seemann, botanist aboard the British survey vessel HMS Herald, described his “disgust” at the “half-castes” he saw at Fort Victoria in 1846, surmising that they “appear to inherit the vices of both races.” Five years later, the first schoolteacher in the Colony of Vancouver Island complained about HBC officers living with Native women.27 Through these laws and others (such as barring Indians from testifying in civil and criminal proceedings), US territorial officials sought to separate Natives from most aspects of white society.

Of all the tribal nations west of the Cascade Mountains, Governor Stevens worried most about the Makahs at Cape Flattery. He knew of their reputation for violence and intransigence. In his report on Indians in the US West, Stevens predicted, “The superior courage of the Makahs, as well as their treachery, will make them more difficult of management than most other tribes of this region. No whites are at present settled in their country; but as the occupation of the territory progresses, some pretty stringent measures will be probably required respecting them.” Characterizing them as “the most formidable [tribe] to navigators of any in the American territories on the Pacific,” Stevens worried that the People of the Cape could interfere with his dream of transforming the territory into a strategic trade link to Asian markets. Situated at the entrance to Puget Sound, angry Makahs could disrupt maritime traffic. But Stevens also knew that he had a timely opportunity to negotiate with the People of the Cape because smallpox had killed the leading chiefs and had left survivors despondent. If he was ever going to badger such a formidable people onto a reservation with other coastal Natives, he felt that this was the moment.28

But Makahs and other Puget Sound Indians were neither as cooperative nor despondent as Stevens hoped. Even before the Potter arrived at Neah Bay, the commissioners had abandoned the goal of placing all American Indians west of the Cascades onto one reservation. Stevens began his treaty negotiations with Puget Sound peoples, who forced him to concede to several reservations rather than one. Like the indigenous leaders Anson Dart had negotiated with previously, the Puget Sound chiefs refused to give up ancestral lands, convincing Stevens that doing so would lead to war. The most dramatic example of this was when Chief Leschi (Nisqually) told Stevens that if he could not get his home, then he would fight. One eyewitness to the incident reported “Leschi then took the paper out of his pocket that the Governor had given him to be sub-chief, and tore it up before the Governor’s eyes, stamped on the pieces, and left the treaty ground, and never came back.” Eventually, Simmons forged the chief’s mark on the treaty.29 Makahs had already refused to join the S’Klallams for the negotiations with Stevens; they insisted on having their own treaty with the United States. Expecting complications, Stevens tried to frighten the Makah chiefs, warning them that “many whites were coming into the country, and that he … did not want the Indians to be crowded out.”30 His threat failed to intimidate the chiefs into leaving Cape Flattery, and the leaders informed him that they would not sell or abandon ancestral lands and waters. Eager to leave Neah Bay with some kind of settlement and fearing the repercussions of angering the People of the Cape, Stevens conceded to Makah demands.

In 1855, Makah chiefs still held enough power to force Stevens to alter a critical clause in the Treaty of Neah Bay. At their insistence, he changed article 4, which detailed their fishing rights, to include whaling and sealing rights (the addition is emphasized): “The right of taking fish and of whaling or sealing at usual and accustomed grounds and stations is further secured to said Indians in common with all citizens of the United States.”31 This small but important alteration made this the only treaty to protect indigenous whaling rights in the continental United States. With the exception of this addition in the Treaty of Neah Bay, all the Stevens treaties contained the same exact language detailing tribal fishing rights.32 The fact that Stevens made this change is important because Makahs forced him to alter his treaty template, something he loathed doing. The Treaty of Neah Bay was the only Stevens Treaty to have this—or any—tribally specific condition beyond particular reservation boundaries.

The smallpox deaths did encourage Makah chiefs to negotiate with Stevens, but not in the way that the governor had hoped. The recent disease mortalities still affected Makahs. Klah-pe at hoo (Claplanhoo), a Neah Bay chief, told Stevens that “he had been sick at heart” since his brother’s death.33 Others also explained that the losses of the ranking chiefs had resulted in their promotion to leading titleholders. But instead of undercutting Makah power, the recent disease experience encouraged the chiefs to approach the treaty negotiations as an opportunity to protect what was important to the People of the Cape. They knew that the dynamics of the ča·di· borderland had changed. The recent smallpox epidemic had slashed Makah numbers, reducing their power and influence among neighboring indigenous peoples, King George men, and Bostons. Perhaps they believed that US acknowledgment of Makah marine tenure in a treaty would protect customary marine space not just from white settlers but also from indigenous rivals.

Makah chiefs appeared to know what to expect from a treaty negotiation. Although this was their first treaty with a colonial authority, indigenous networks of trade and kinship had brought news of other such negotiations. Between 1850 and 1854, James Douglas, as governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island, negotiated fourteen treaties with Natives north of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. On the surface, these were little more than land purchases. Douglas paid the “Swengwhung” (a band of Lekwungens) of Victoria Peninsula HBC blankets valuing £75 for their land in April 1850. Through these negotiations, these Lekwungens secured for themselves a small reserve and hunting and fishing rights in customary areas.34 Makahs would have also known of the 1851 Dart Treaties, particularly the Tansey Point Treaty, signed with Quinaults and neighbors to the south.35 These earlier British and US treaties gave Makah chiefs certain expectations for their own treaty: payment for lands they conceded, protection of key ancestral lands, and guaranteed fishing and hunting rights. These earlier negotiations provided Makahs with the notion that treaties could benefit their people.

Makahs today remember the treaty negotiations as a time when ancestors fought for their way of life. This conclusion aligns with oral histories kept by other tribal nations that were parties to Stevens’s treaties. Ted Strong (Yakama) speaks of his people’s belief that their chiefs saw the 1855 Yakama Treaty as “an instrument to preserve life for our tribal nation…. Our treaty was looked upon by our leaders as a way of preserving what tribal members were left after decimation by war, by diseases and a reduction in the quality of life because of the encroachment of a new order of people and society that was coming to the Northwest.” Makahs still speak of the treaty as a document in which they “kept the sea” for themselves.36

MAKAH MARINE TENURE IN THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY

In 1855, Makah chiefs believed that keeping the sea for the People of the Cape was paramount. By calling the sea his country during the treaty negotiations,  aq

aq ·wi

·wi expressed Makah tenure over customary marine waters and resources. During the mid-nineteenth century, tenure meant ownership of land, according to the doctrine of property that predominated in the United States and Britain.37 Americans and Britons understood that ownership was exclusive and gave the owner the right to buy and sell her or his property and to manage the land as he or she saw fit. But ownership was not absolute within the context of modern nations. Through legal institutions and political bodies, societies have exercised constraints over both the use and allocation of property, including taxation and regulatory powers, such as policing and zoning. The existence of tribal marine tenure extends traditional scholarship on indigenous peoples that limits Native tenure concepts to terrestrial spaces. Many studies on American Indians examine the relationship of a particular people to its land and related resources, defining land as the foundation of tribal identity.38 This terrestrial perspective overlooks those indigenous peoples, such as Makahs, who vested marine rather than terrestrial spaces and resources with their most valued tenure rights.

expressed Makah tenure over customary marine waters and resources. During the mid-nineteenth century, tenure meant ownership of land, according to the doctrine of property that predominated in the United States and Britain.37 Americans and Britons understood that ownership was exclusive and gave the owner the right to buy and sell her or his property and to manage the land as he or she saw fit. But ownership was not absolute within the context of modern nations. Through legal institutions and political bodies, societies have exercised constraints over both the use and allocation of property, including taxation and regulatory powers, such as policing and zoning. The existence of tribal marine tenure extends traditional scholarship on indigenous peoples that limits Native tenure concepts to terrestrial spaces. Many studies on American Indians examine the relationship of a particular people to its land and related resources, defining land as the foundation of tribal identity.38 This terrestrial perspective overlooks those indigenous peoples, such as Makahs, who vested marine rather than terrestrial spaces and resources with their most valued tenure rights.

Settler-colonial nations and empires have used tenure concepts to their advantage in order to dispossess indigenous peoples of land and terrestrial resources.39 During the North American colonial period, expanding empires acknowledged varying degrees of indigenous tenure rights to enable them to purchase Native lands or to seize vast tracts through “just wars.” During the treaty era, the United States recognized American Indian tenure in order to negotiate for land cessions, just as Governor Stevens did during the 1855 Treaty of Neah Bay. Congressional legislation, such as the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887, granted ownership rights to individuals to fragment tribal holdings and to transfer more land out of American Indian hands. Like other Western concepts applied to indigenous peoples, tenure has a long history of being used to the advantage of the colonizer.40 Therefore, when discussing indigenous tenure, we must differentiate it from the version of market capitalism–style tenure that predominated in the United States. For Makahs of the mid-nineteenth century, tenure included sentimental and spiritual components and entailed rights and responsibilities that owners possessed and maintained.

In North America, indigenous tenure concepts and protocols varied from one society to the next and over time. Like their Nuu-chah-nulth relatives, Makahs observed a complex system of ownership rights encompassing nearly every cultural and material item, including propertied spaces. When Europeans and Euro-Americans encountered Northwest Coast peoples during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, many complained that everything—driftwood, fish, shellfish, game, sea mammals, timber, wild plants, and freshwater—appeared to have an owner. In the early 1940s, Makah elder Henry St. Clair explained that ownership rights were tied to specific marine and terrestrial places. Called tupa·ts (“too-pahts”), these property items included intangible objects, such as songs, names, and stories, and places like fishing or hunting grounds, beaches, and other identifiable spots. No one was allowed to remove or harvest anything from someone’s tupa·t unless they had permission. Anything that came into a tupa·t belonged to the owner of that place. If someone found something of value, such as a drift whale, in another person’s tupa·t, he or she was supposed to tell the owner, who in turn paid the informant. People with tupa·ts threw regular feasts in order to remind everyone where their property was and who owned it. Tupa·ts continued to be relevant to the People of the Cape until at least the early twentieth century.41

As non-Natives became more familiar with indigenous societies of this corner of the Pacific, they learned that ownership rights extended to cultural property. These included names, songs, dances, games, stories, rituals, and privileges to practice particular occupations, such as whaling. Northwest Coast peoples embedded ownership rights within social hierarchies. Chiefs held the most important resources and hunting, fishing, and gathering areas, including cranberry bogs, locations for fishing weirs, and offshore fishing grounds. They managed and monitored use of these resources and extended usufruct rights—the right to use something owned by someone else—to family members and others, even possibly to non-Makahs on an occasional, case-by-case basis. Makah oral histories differ on this point. Some recall hearing elders mention that they allowed non-Makah Indians with kinship ties to a Makah family to fish propertied grounds on an occasional basis, whereas others state that non-Makahs never fished tribal grounds. Regardless, when the People of the Cape occasionally allowed non-Makah Natives to fish in customary waters, they did not transfer ownership rights to these people; nor did it make these sites part of the collection of “usual and accustomed grounds” non-Makahs could claim under a treaty.42 In 1941, Makah elders explained to an attorney connected to the federal Indian Office that their ancestors never fished an area that did not belong to them unless the owner invited them to do so.43 While Makahs of the mid-nineteenth century owned many terrestrial resources and lands, the ocean around Cape Flattery was their most valuable property.44 They rooted their marine tenure rights within the very fabric of what made them Makah—cultural practices and performances related to the marine environment.

A combination of natural forces made Makah home waters off Cape Flattery a complex marine environment. Fluctuating winds, nearby mountains and watersheds, submarine geological features, circulating water masses, and a rich marine ecosystem interacted to create Makah marine space. Located just off the cape, the Juan de Fuca Eddy drew rich nutrients from the cold ocean depths to the surface. This upwelling fueled a food web that included a wide variety of fish, seabirds, and marine mammals—especially whales—which were culturally significant to Makahs. While scholars characterize the entire Northwest Coast region as a rich marine environment, substantial variations occurred from one place to the next and over time. Because of the Juan de Fuca Eddy, customary Makah waters were some of the most consistently plentiful marine environments in the region.45

Societies conceptualize spaces as more than a collection of places people use. We can best understand spaces as social realities with sets of forms and relations; societies use culturally specific processes to transform “amorphous space into articulated geography.”46 Focusing on the maritime space of Torres Strait Islanders between the Australian continent and New Guinea, one geographer argues that “sea territories are not just bounded sea space but areas named, known, used, claimed and sometimes defended. A social group’s familiarity with an area creates a territory. A territory, whether terrestrial or marine, is more than simply spatially delimited and defended resources for the exclusive use of a particular group. A territory is social and cultural space as much as it is resource or subsistence space. Sea space becomes an entity because a social group establishes and recognizes the location, pattern and interaction of marine things and processes.”47 These ideas confirm what Chief Umeek (Richard Atleo), a hereditary chief of the Ahousaht First Nation, has explained about his people today: “There is a direct relationship between membership in a community and the resources of that community.”48 The People of the Cape, then, expressed membership within their community through the ways they experienced local marine space and related to and relied on the resources within their waters.

Makahs expressed tenure over these bountiful waters through indigenous knowledge of local spaces. During the treaty negotiations,  alču·t, the first Makah leader to speak on behalf of his people, connected knowledge to tenure rights. When introducing himself to Governor Stevens,

alču·t, the first Makah leader to speak on behalf of his people, connected knowledge to tenure rights. When introducing himself to Governor Stevens,  alču·t stated, “I know the country all around and therefore I have a right to speak” about Makah ownership of the sea and their fishing rights.49 One of the highest-ranking chiefs, he owned important marine resources, such as specific halibut fishing banks just off the coast, and his family had fished them for generations. The “country” he and other Makahs described was the ocean around the Cape Flattery villages, which provided access to lucrative fishing, whaling, and sealing grounds. Their familiarity with the area transformed this portion of the Pacific into Makah home waters to which they held title.

alču·t stated, “I know the country all around and therefore I have a right to speak” about Makah ownership of the sea and their fishing rights.49 One of the highest-ranking chiefs, he owned important marine resources, such as specific halibut fishing banks just off the coast, and his family had fished them for generations. The “country” he and other Makahs described was the ocean around the Cape Flattery villages, which provided access to lucrative fishing, whaling, and sealing grounds. Their familiarity with the area transformed this portion of the Pacific into Makah home waters to which they held title.

Like other societies, Makahs articulated their ownership and knowledge through place-naming. Using examples from Western Apaches, anthropologist Keith Basso explains how the process of place-naming invests spaces with social meaning by invoking stories that teach culturally specific values. Place-names also encode cultural knowledge that reflects subsistence patterns and a people’s understanding of geography and natural forces. Among Torres Strait Islanders, “Names acknowledge familiarity with places…. Place names provide traditional title to land and sea territory. History and tenure are confirmed by places named.” Stó:lō scholar Albert McHalsie reminds us that place-names “transform our landscape from what others consider a terra nullis (‘empty land’) into a place where our ancestors continue to live in spirit.” Makahs also employed place-names in ways similar to Apaches, Stó:lös, and Torres Strait Islanders to transform the sea into their home.50

Archival records before, during, and after the nineteenth century illustrate the importance of marine place-naming to Makahs. During the 1792 Galiano and Valdés expedition to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Spaniards noted several Makah names for harbors, river mouths, islands, passages, and other marine features. The geographic breadth of these names demonstrates that Makah mariners knew the entire Strait of Juan de Fuca and northern Puget Sound. Makahs still remembered many of these place-names into the late twentieth century, reflecting the continued importance of these sites both off-reservation and on the Canadian side of the border.51 While residing at Neah Bay in the decades after the Treaty of Neah Bay, James Swan, the first Euro-American teacher on the reservation, noted many Makah place-names for marine locations. Some identified fishing grounds over which specific families and villages held particular usufruct rights. In his unpublished manuscript on Makah geography of the early twentieth century, anthropologist T. T. Waterman recorded 144 marine place-names (64 percent) out of a total 224 from the Cape Flattery region. Examples ranged from named sea stacks (vertical columns of rock formed by coastal erosion) to submerged rocks to particular spots on beaches. The high densities of place-names demonstrate the People of the Cape’s long-term occupation and intimate knowledge of these places.52

The naming of Tatoosh Island exemplifies how Makahs used names to articulate indigenous knowledge, history, and values. The island actually has several names. Hupačakt (“hoo-puh-chuhkt,” island) was one of the original Makah names for the island.53 But from the eighteenth century, the People of the Cape have referred to it more frequently as Tatoosh Island, its current name. Ditidahts, a group of Vancouver Island Nuu-chah-nulths and close relatives of Makahs, named the island Too-too-tche, the Nootkan word for Thunderbird, a powerful, supernatural being. According to John Claplanhoo, a mid-nineteenth-century Makah chief, “[Thunderbird] is in all aspects like an Indian and feeds on whales. When he is hungry he clothes himself with wings and feathers, as he would put on a blanket and soars away like a vast cloud over the ocean. When he sees a whale he throws down the Ha hake to ak—an animal like the sea horse—who with his red tongue causes the lightning by thrusting it out like a snake. This stuns or kills the whale when the Thunderbird seizes it with his talons and carries it home for food. The rustling of its wings causes the thunder.”54 Accounts such as this illustrate the cultural belief that Thunderbird taught Makahs and Nuu-chah-nulths to whale. To mid-nineteenth-century Makahs, Thunderbird was not a mythological relic of the past—he was still physically present. George Gibbs spoke with one Makah whaler who encountered Thunderbird while chasing a whale. Thunderbird appeared and plucked the whale from the water, “causing a great commotion … and nearly capsizing the canoe.”55 Therefore, when Ditidahts named Tatoosh Island, they were recognizing this as one of the premier whaling sites in the ča·di· borderland. The People of the Cape accepted this name, even though Ditidaht oral histories purport that they once claimed the island.56 Makahs adopted Tatoosh as an honored name that prominent whaling chiefs earned the right to hold as any other ceremonial property.

More than just expressing ownership, indigenous knowledge of this named marine country allowed Makahs to navigate it safely and to exploit its resources. When on the water, they used both landmarks and seamarks to pinpoint their location. Fishers located fishing spots by referencing features along Vancouver Island and the Olympic Peninsula. To help them locate usual places where migrating fur seals slept, sealers noted the difference between shallower inshore waters and the deeper “blue sea” above the submerged continental shelf. They also knew the locations of regular kelp beds and used them as overnight anchorages when away from their villages, just as the Nuu-chah-nulth canoe fleet did in 1852 when intimidating the US Pacific Survey at Cape Flattery. Whaling crews occasionally lost sight of land and stayed out on the tu ał (“too-puhlth,” ocean) for days. On clear evenings, they steered by the pole star. Combinations of regular swell patterns and winds enabled them to fix their approximate location, even in the regular fogs that conceal the coast. Experienced Makah mariners also used the water’s appearance and the set of the riptide to approximate their location when out of sight of land.57

ał (“too-puhlth,” ocean) for days. On clear evenings, they steered by the pole star. Combinations of regular swell patterns and winds enabled them to fix their approximate location, even in the regular fogs that conceal the coast. Experienced Makah mariners also used the water’s appearance and the set of the riptide to approximate their location when out of sight of land.57

Spending so much time on the water, the People of the Cape also needed to understand and be able to predict local weather. Individuals with the most developed weather-prediction skills were “broadcasters” who advised fishers, sealers, and whalers when to go out. Makahs embedded this indigenous knowledge in cultural terms. They had two months that they named after the changing weather conditions.  ułačaktpał (“kloo-lthuh-chuhkt-puhlth”), their equivalent of February, marked the beginning of good weather, indicating that it was safe to canoe alone.

ułačaktpał (“kloo-lthuh-chuhkt-puhlth”), their equivalent of February, marked the beginning of good weather, indicating that it was safe to canoe alone.  a

a a·

a· uqšpał (“tsuh-tsah-ooksh-puhlth”) began in late November, and its name means “month of winds and screaming birds.” They also differentiated between certain weather phenomena on land and at sea. Łutka·bałid (“lthoot-kah-buh-lthihd”) means “thunder on the ocean.”58 For Makahs, this term not only recognized that thunder sounds different on the ocean, but it also signified the whaling power of Thunderbird, who causes thunder on the ocean when he whales.

uqšpał (“tsuh-tsah-ooksh-puhlth”) began in late November, and its name means “month of winds and screaming birds.” They also differentiated between certain weather phenomena on land and at sea. Łutka·bałid (“lthoot-kah-buh-lthihd”) means “thunder on the ocean.”58 For Makahs, this term not only recognized that thunder sounds different on the ocean, but it also signified the whaling power of Thunderbird, who causes thunder on the ocean when he whales.

Makah ability to predict the weather impressed non-Indians. In 1863, James Swan reported that Makahs recognized that the clamor of birds and a particular type of swell preceded storms. The swell caused “strange noises” to emanate from the rocky caverns on Cape Flattery; Makahs believed that “Indians who have been drowned about the Cape, whose office it now is to warn other Indians of impending danger,” made these sounds. When fishers and sealers on the water heard these noises, they had just enough time to round the cape and seek safety in Neah Bay before the storm hit. In a separate account, Swan also recorded the ability of Makahs and neighboring peoples to predict upcoming seasons of especially unpleasant weather. Toward the end of September 1865, he wrote in his diary, “Capt. John [Claplanhoo] tells me that the Indians predict a very cold winter. There will be according to his statement, very high tides, violent gales, great rains, much cold and snow. The Arhosetts [Ahousahts on Vancouver Island] predict rain from an unusual number of frogs in a particular stream at their place. The Oquiets [Ohiahts on Vancouver Island] predict cold from the fact that great numbers of mice were seen leaving an island in Barclay Sound and swimming to the mainland.” His entries that winter noted the conditions his “informants” had predicted. This level of familiarity with their home illustrated ways the People of the Cape made the sea their country.59

Makah knowledge of their marine environment also extended to the biological resources within it. This allowed them to adapt gear and techniques to harvest a range of oceanic foods and materials. Similar to indigenous knowledge of the local environment, the work they did in these waters also expressed tenure. Statements made by Makah chiefs during the treaty negotiations demonstrate that they understood the connection between labor and ownership. In the same breath as they spoke of their ownership of the sea, they detailed the importance of maritime work, such as catching halibut and hunting whales. By mixing their labor with the ocean through customary marine practices, Makahs transformed the sea into their country.60

Makah sealers drew upon indigenous knowledge to hunt two species of seals,  iładu·s (“kih-lthuh-doos,” fur seals) and

iładu·s (“kih-lthuh-doos,” fur seals) and  a·š

a·š u

u u (“kahsh-choo-oo,” hair seals), the former at sea and the latter in caves dotting Cape Flattery. The customary practice of sealing, something they had done for generations, also expressed Makah tenure of their marine country. Sealers embarked from winter villages at 2:00 a.m. to take advantage of the east wind that propelled their canoes, rigged with sails woven from cedar bark, out to the ocean. They went ten to forty miles into the Pacific, reaching the hunting grounds at daylight in order to catch herds of sleeping fur seals. From January to May, the Davidson Current, which carries warmer, equatorial-type water along the Washington coast, brings migrating seals close to shore. In fair weather, sealers stayed on the water for more than twenty-four hours, lighting fires in their canoes to stay warm.61

u (“kahsh-choo-oo,” hair seals), the former at sea and the latter in caves dotting Cape Flattery. The customary practice of sealing, something they had done for generations, also expressed Makah tenure of their marine country. Sealers embarked from winter villages at 2:00 a.m. to take advantage of the east wind that propelled their canoes, rigged with sails woven from cedar bark, out to the ocean. They went ten to forty miles into the Pacific, reaching the hunting grounds at daylight in order to catch herds of sleeping fur seals. From January to May, the Davidson Current, which carries warmer, equatorial-type water along the Washington coast, brings migrating seals close to shore. In fair weather, sealers stayed on the water for more than twenty-four hours, lighting fires in their canoes to stay warm.61

Sealers used specially designed silent canoes to approach the sleeping herd, getting close enough to hear individual fur seals snore.62 Twenty-four feet long, these canoes held a three-man crew—a harpooner and two paddlers—and up to fifteen carcasses. Canoe makers constructed these vessels to ride high in the water so that the harpooner could more easily see his prey, and they scorched the bottoms to burn off splinters that might make noisy ripples and wake sleeping seals. Paddlers approached from the leeward side of the herd so that the seals could not smell them coming. When the canoe got within twenty feet of the prey, the hunter hurled a fifteen-foot harpoon shaft mounted with two barbed spearheads. The best harpooners sometimes only needed one throw with the double-headed harpoon to strike two seals sleeping side by side. Attached to lines sixty feet long and to buoys made from inflated sealskins, the harpoon heads detached from the shaft when they struck. Then the hunters hauled the seal toward the canoe and clubbed it dead. In the afternoon, they took advantage of the west wind to carry them home.63

Pelagic (oceanic) sealing entailed a certain amount of manageable danger. Like other wild animals, injured seals bite. When dragged close enough to club, seals lashed out, biting limbs and sometimes even gouging canoes. A combination of thrashing fur seals and turbulent waters occasionally overturned canoes. One Makah sealer recounted a time when his canoe overturned and dumped him, his brother, their little white dog, and bleeding seal carcasses into the ocean off Tatoosh Island. This attracted nearby sharks that circled and made “savage runs” at them and the dead seals.64 Sudden storms could sweep sealers far out to sea. In 1874, a ship bound for Asia picked up a canoe of Makahs that a storm had forced far offshore; the sealers switched to another vessel bound for San Francisco and returned home two months later.65 Indigenous knowledge allowed Makah sealers to minimize these dangers and to hunt this marine resource with some predictability and safety.

Of all their customary practices, whaling best demonstrates how the People of the Cape combined indigenous knowledge with labor to express marine tenure. Makah whalers have relied on their knowledge of the marine environment to hunt leviathans for the past two thousand years. Through the mid-nineteenth century, most whalers caught one or two  i

i apuk (“chih-tuh-pook,” whales) annually and as many as five in good years. Primarily hunting sixwa·wi

apuk (“chih-tuh-pook,” whales) annually and as many as five in good years. Primarily hunting sixwa·wi (“sih-hwah-wihk,” California gray whales) and

(“sih-hwah-wihk,” California gray whales) and  i

i iwad (“chih-chih-wuhd,” humpbacks), whalers also occasionally harvested

iwad (“chih-chih-wuhd,” humpbacks), whalers also occasionally harvested  u·cqi (“koots-kee,” sperm whales),

u·cqi (“koots-kee,” sperm whales),  i·

i· up (“ee-choop,” right whales), ka·

up (“ee-choop,” right whales), ka· a·p

a·p  apa·wad (“kah-uhp uh-pah-wuhd,” fin whales), and even

apa·wad (“kah-uhp uh-pah-wuhd,” fin whales), and even  i

i iš

iš ał (“ih-ihsh-pulth,” blue whales). They also took

ał (“ih-ihsh-pulth,” blue whales). They also took  wa

wa w

w aq

aq i· (“kwuhk-uhk-klee,” porpoises),

i· (“kwuhk-uhk-klee,” porpoises),  i·ł

i·ł u· (“tseelth-koo,” dolphins), saba·s (“suh-bahs,” sharks), and kawad (“kuh-wuhd,” orcas).66

u· (“tseelth-koo,” dolphins), saba·s (“suh-bahs,” sharks), and kawad (“kuh-wuhd,” orcas).66

Makah rock art at Ozette, 1905. Photograph by Edmond S. Meany. University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, NA1274.

Successful whalers possessed knowledge and experience specific to particular species of whales, information guarded and passed from father to son, just as whaling gear was. The Claplanhoo family remembers a harpoon that fathers had passed to sons since the mid-eighteenth century. In 1907, this device had 142 notches on it for the whales Claplanhoo whalers had killed with it. The crew of eight, assembled by the harpooner, sometimes remained on the ocean for days at a time, fifty to a hundred miles away from shore, pursuing  i

i apuk. A whaler harpooned his prey several times and then bled it to death with a lance amid “great fountains of crimson spray.” In extreme cases, a whaler would leap onto a harpooned whale that took too long to die. He held onto the lines connecting the whale to the canoe while stabbing the leviathan to dispatch it. Whalers even practiced holding their breath underwater in case they needed to hold onto submerging whales in these situations. Once the whale was dead, a naked diver sewed shut its mouth to prevent it from sinking. Then the crew towed the whale back to the coast, sometimes taking three days to get it ashore. Staying out for this length of time and paddling across such great distances required Makah whalers to rely on their knowledge of the ocean environment and their navigational and weather-prediction skills within a large marine area.67

apuk. A whaler harpooned his prey several times and then bled it to death with a lance amid “great fountains of crimson spray.” In extreme cases, a whaler would leap onto a harpooned whale that took too long to die. He held onto the lines connecting the whale to the canoe while stabbing the leviathan to dispatch it. Whalers even practiced holding their breath underwater in case they needed to hold onto submerging whales in these situations. Once the whale was dead, a naked diver sewed shut its mouth to prevent it from sinking. Then the crew towed the whale back to the coast, sometimes taking three days to get it ashore. Staying out for this length of time and paddling across such great distances required Makah whalers to rely on their knowledge of the ocean environment and their navigational and weather-prediction skills within a large marine area.67

Canoes at Neah Bay, 1900. The canoe in the foreground is filled with sealskin floats used in whaling. Photograph by Anders B. Wilse, courtesy Museum of History and Industry, Seattle.

Laboring in their country, the sea, Makah families harvested enormous quantities of marine products during the mid-nineteenth century. The wealth they earned from these products allowed them to wield significant authority and power in the ča·di· borderland. Abetted by indigenous knowledge, access to unique trade goods harvested from halibut, seals, and whales enabled the Makah to establish their middleman position in regional trade networks before the appearance of Europeans. The People of the Cape maintained their influence by exchanging customary marine products with non-Native traders during the postcontact decades. In the early encounter years, non-Natives desired sea otter pelts; other products increased in importance during the first half of the nineteenth century. Seals provided Makahs with several valuable subsistence and commercial products. The People of the Cape ate the flesh, rendered the blubber into oil, used the skin for bedding, and employed the bladder to store sea mammal oil. From entire hair sealskins that they inflated, whalers made floats used when hunting. They often employed thirty to forty of these buoys to slow down and tire out harpooned whales, and these prevented the heavy carcass from sinking. During the second half of the nineteenth century, fur sealskins became an important commodity that Makahs traded with whites on both sides of the strait.68

Mid-nineteenth-century Makahs profited most from the trade of whale products. Popular assumptions about indigenous peoples emphasize the subsistence aspect of hunting, fishing, and gathering while minimizing or ignoring the commercial importance of these customary practices in the past. However, archaeological analysis of sea mammal remains at Ozette demonstrates that Makah whalers took far more whales than they could consume—whaling during the centuries before the arrival of Europeans and global markets in whale products was nonetheless a commercial activity. Indigenous peoples of the ča·di· borderland prized whales for their flesh, sinew, blubber, oil, and bones. As with halibut and seal meat, women smoked whale flesh, which spoils more quickly than blubber. Makahs ate blubber fresh and hung the remainder in smoke to cure it like bacon. Non-Natives who tried dried blubber thought it tasted like sweet pork. The People of the Cape used the bones as tools—spindle whorls, bark shredders, bark beaters, mat creasers, clubs, wedges, and tool handles—and structurally in water diversion efforts and as retaining walls to help stabilize small mudslides. But whale oil was the most important subsistence and commercial product harvested. After stripping the blubber from a carcass, women boiled it and used clamshells to skim off the oil as it rose to the surface. Makahs stored processed oil in bladders and consumed it like butter, dipping dried fish, potatoes, and berries in it. In earlier times, the People of the Cape traded whale oil among themselves and with neighboring peoples, measuring out precise quantities of this valuable commodity with a two-and-a-half gallon bucket made from a pelican’s beak.69

While Makahs valued the material goods the sea provided, their marine country and the resources within it had an importance beyond economic terms. Unlike forms of tenure that predominated in the United States during the first half of the nineteenth century, Makah tenure had sentimental—even spiritual—components. By mixing their labor with the sea, they communicated a “bond of belonging.”70 In writing about Hispano loggers’ belief that they owned the forests of northern New Mexico, anthropologist Jake Kosek reminds us that “sentimental arguments over nature are often considered the antithesis of rational discourse about property rights.” Applied to American Indians, scholars mistakenly dismiss these sentiments as stereotypes of the Ecological Indian.71 For Makahs, their bond with the sea has been and continues to be far more complex. When  aq

aq ·wi

·wi described the sea as his country, he invoked the Makahs’ spiritual bond with the waters around Cape Flattery. His words referenced the ways they owned marine space, used customary practices to express tenure rights, and exploited the ocean’s bounty to gain wealth and power.

described the sea as his country, he invoked the Makahs’ spiritual bond with the waters around Cape Flattery. His words referenced the ways they owned marine space, used customary practices to express tenure rights, and exploited the ocean’s bounty to gain wealth and power.

During the nineteenth century, Makahs recognized that tenure often entailed both rights and responsibilities.72 These rights included usufruct rights, and high-ranking leaders decided who else could share the property in question and on what terms.73 Makahs embedded tenure concepts within a larger worldview that recognized “numinous forces” in their environment and that the spiritual and physical realms are one, so they understood that ownership also entailed responsibility.74 The People of the Cape believed they were responsible for maintaining a balanced relationship with a community that included the very animals and fish that they harvested. For most indigenous cultures, the “community extends beyond human relationships.”75 But we should not misconstrue this as Makahs acting like proto-ecologists. Hunting thousands of seals and harpooning dozens of whales annually illustrate that Makahs cannot be stereotyped as Ecological Indians. More than anything else, their belief that marine tenure entailed responsibility differentiates the Makahs’ understanding of ownership from similar concepts that predominated in the nineteenth-century United States.

The worldview of the People of the Cape related spirituality with responsible stewardship. From their perspective of a “sacred ecology,” most animals, plants, and prominent landmarks were nonhuman people.76 Billy Balch, one of Swan’s “informants” and Chief Yela ub’s son, told Swan that Makahs believed that everything—including trees, animals, birds, and fish—were “formerly Indians who for their bad conduct were transformed into the shapes that now appear.”77 Balch told Swan that Seal was once a thief, so the brothers Sun and Moon shortened his arms and tied his legs. They then cast him into the sea and told him to eat only fish. Sharing a common origin and designation as people, everything deserved respect, which Makahs demonstrated through protocols, laws governing the relationships between human and nonhuman beings. Northwest Coast peoples continue to believe that “the land, the plants, the animals and the people all have spirit—they all must be shown respect. That is the basis of our law.”78 Through stories elders told, Makahs learned that protocols kept relationships balanced and that violating these laws had consequences. Makahs also embedded their worldview in the marine-oriented, spatial context of the geography around Cape Flattery. “Se kar jecta” was an “evil genius”—probably a powerful shaman—who had transformed into a large rock off the coast south of the cape. On two separate canoe trips, Swan observed Makahs throwing offerings of bread, dried halibut, and whale blubber at Se kar jecta in order to ensure their safe passage.79

ub’s son, told Swan that Makahs believed that everything—including trees, animals, birds, and fish—were “formerly Indians who for their bad conduct were transformed into the shapes that now appear.”77 Balch told Swan that Seal was once a thief, so the brothers Sun and Moon shortened his arms and tied his legs. They then cast him into the sea and told him to eat only fish. Sharing a common origin and designation as people, everything deserved respect, which Makahs demonstrated through protocols, laws governing the relationships between human and nonhuman beings. Northwest Coast peoples continue to believe that “the land, the plants, the animals and the people all have spirit—they all must be shown respect. That is the basis of our law.”78 Through stories elders told, Makahs learned that protocols kept relationships balanced and that violating these laws had consequences. Makahs also embedded their worldview in the marine-oriented, spatial context of the geography around Cape Flattery. “Se kar jecta” was an “evil genius”—probably a powerful shaman—who had transformed into a large rock off the coast south of the cape. On two separate canoe trips, Swan observed Makahs throwing offerings of bread, dried halibut, and whale blubber at Se kar jecta in order to ensure their safe passage.79

Like other Northwest Coast peoples, Makahs believed that the nonhuman members of their community possessed power and punished those who failed to observe protocols correctly. Cedakanim, a mid-nineteenth-century Clayoquot chief whose son was married to a Makah woman, told Swan about a time when sea otters had vengefully drowned the son of a chief, who was a successful hunter of the species. The chief exacted his revenge by killing a great number of sea otters and feeding their dried hearts to his dogs, a serious sign of disrespect. This severe protocol violation insulted the otters, and they left the coast. Although Nuu-chah-nulths and Makahs had hunted sea otters to near extinction in the ča·di· borderland during the maritime fur trade, some blamed a high-ranking chief’s behavior for the dearth of otters. His disrespectful behavior to nonhuman people resulted in both personal (a drowned son) and society-wide (sea otters abandoned the coast) consequences. Therefore, chiefs were most responsible for maintaining respectful relationships with nonhuman members of the community.80 Makahs blamed the poor salmon and sealing seasons in 1879 on a chief who had allowed his pregnant wife to eat of the first salmon of the season. This resulted in the deaths of her and their unborn twins and caused salmon to leave the rivers and seals to flee.81 For commoners, it appears that the consequences for disrespectful behavior were personal, whereas the actions of chiefs had both personal and societal consequences, explaining why leaders took seriously their responsibilities to follow correct protocols.

The spiritual dimensions of the whaling practice best exemplify how Makahs honored and propitiated the nonhuman members of the marine community. To become a “skookum whaleman” (strong whaler), a harpooner—who was also the captain of a whaling crew—needed supernatural powers. Because a harpooner’s success at whaling relied on his ability to interact with a nonhuman person possessing greater spiritual strength, he needed additional powers. Makahs believed that humans normally possessed limited supernatural power and ability, especially in comparison to a powerful being such as a whale. Whaling included both physical and spiritual hazards. To meet these challenges, whalers sought spiritual assistance through ceremonial practices. Prayers could help someone attain a power, and dreams could also grant a power or reveal how to earn it. To secure these supernatural powers, an individual performed specific actions, such as ritual bathing, or scoured the woods and beaches for signs of power. Whalers also sought guardian spirits whose supernatural strength would protect the crew.82

Makahs believed that acquiring “whale medicine” ensured one’s success at sea and augmented an individual’s authority within the community. A spar that waves had thrown to the top of a nearby sea stack enticed many whalers for years. They devised methods to retrieve the inaccessible spar because they believed that they could craft it into a harpoon shaft that would bring its owner immense whaling luck. John Claplanhoo told Swan several stories of whale medicine he or his family members had received. One time, “raven lit on a stone a few feet off and ruffling up his feathers as they do when angry, first uttered a hissing sound and then a croak, and opening his beak wide twice to vomit up something,” a bone, three inches long. Claplanhoo believed that this was a bone of the  i