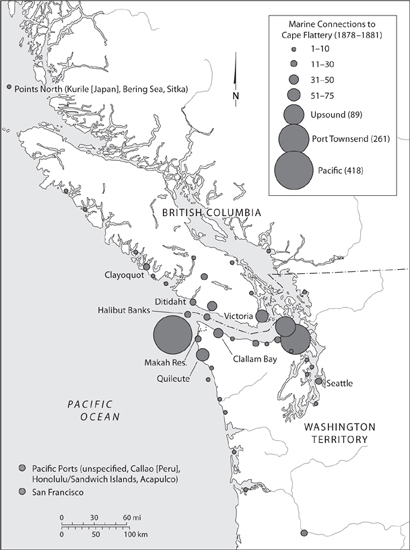

In June 1865, Henry Webster, US Indian agent at Neah Bay, composed the agency’s annual report for the commissioner of Indian affairs, characterizing his Makah charges as “an anomaly in the Indian service.” From his vantage at the most northwestern point of the United States, the people living in a collection of cedar longhouses hugging the rugged shore of Cape Flattery must have appeared this way. Violent storms swept across heavily forested, mountainous terrain and regularly dumped more than a hundred inches of rain each year. With the nearest US settlement several days away by Indian canoe, Neah Bay felt isolated from the world. After one of his earliest visits to Cape Flattery, James Swan described Webster as living an “almost Robinson Crusoe residence on this bleak, extreme northwest portion of the domain of the United States … the farthest west of any settlers on American soil.”1 But in this seemingly isolated and unwelcoming environment of Cape Flattery, Makahs anomalously thrived.

This was no “bleak,” remote edge of the world for the indigenous people who made this their home. Networks of trade, kinship, and conflict knit together village communities and growing non-Native towns in the ča·di· borderland and Puget Sound. Makah whalers, sealers, and fishers harvested a wealth of resources from customary waters. Agent Webster reported that they did not “procure a scanty and temporary supply, but have abundance to dispose of in trade with the Indians and whites.” He advised the commissioner that the federal government should encourage their fisheries so that they could remain self-supporting and attain a “state of civilization.” This also made them anomalous to the Indian service: rather than civilizing Makahs by transforming them into Jeffersonian yeoman farmers, Webster contradictorily believed that the federal government should support customary marine practices to help them progress.2

Perhaps the People of the Cape appeared anomalous to Agent Webster in a third way, for he came from a culture that defined whites and Indians as opposites.3 Euro-Americans pictured themselves as modern, civilized, prosperous, masculine, and dynamic, believing themselves to be agents of the future who would usher in progress and develop the Northwest Coast wilderness. Conversely, American Indians were supposed to be traditional, uncivilized, impoverished, feminine, childlike, and static. Nearly all non-Natives saw Indians as a part of nature, relics of the past, and impediments to the inevitable progress and economic development of the continent. Men like Webster regarded Makahs as anomalous because they did not fit the Indian stereotype.4 During the second half of the nineteenth century, the People of the Cape bought and used expensive vessels and prospered as dynamic actors in regional and international markets of exchange. Their labor in modern extractive industries of the North Pacific strengthened their ability to continue living as Makahs even though the United States attempted to tighten control over indigenous peoples in the West. They labored and engaged in new economic experiences in order to maintain cultural practices, thereby establishing new paths to capitalist development.5 Agent Webster witnessed the beginning of a Makah version of economic development that was part of the rise of indigenous entrepreneurs in Gilded Age America.

Some historical narratives that detail the rise of regional and global markets continue to cast indigenous peoples as either tragic victims or ignorant dupes who could only accept or react to European and Euro-American actions and changes. These narratives simplify the role of indigenous peoples in commercial exchanges. Natives appear at the fringes, as peripheral hunters or fishers swept aside or exploited by dynamic non-Natives, “the utmost antithesis to an America dedicated to productivity, profit, and private property.”6 These characterizations obscure the way indigenous entrepreneurs created roles for themselves within market societies in order to maintain and strengthen distinct cultural identities. Reports such as those written by Agent Webster perpetuated this false conclusion and framed successful Makahs as anomalous, as the exception to the rule.

A marine-oriented approach to Makah history of the late nineteenth century reveals that these whalers, sealers, and fishers combined new opportunities and technologies with customary practices to maintain their identity, much as other Native peoples of North America did as they confronted settler-colonialism and growing capitalist markets.7 Rather than allowing expanding networks of capital to overwhelm and replace indigenous practices, these fishers and sea mammal hunters engaged markets of exchange and attracted—even made—capital investments in North Pacific extractive industries. When examined from a Makah perspective, these actions reveal dynamic, indigenous actors who exploited new opportunities within their own cultural framework. The subsequent success of the People of the Cape stemmed from measures Makah chiefs had taken to protect access to customary marine space while negotiating the 1855 Treaty of Neah Bay.

During this period, the Claplanhoo family exemplified Makah prosperity. Prominent patriarchs such as John, James, and Jongie emerged as indigenous entrepreneurs and occupied the ranks of tribal leadership for more than a century, from the early 1850s to the late 1950s. Although James engaged in the pelagic sealing industry and Jongie both sealed and fished commercially, all three Claplanhoo chiefs whaled. Similar to other Northwest Coast whaling chiefs, these men married women from prominent families around the ča·di· borderland, which enabled them to maintain close ties with influential in-laws. In 1860, John married Ši· a·štido (“shee-ahsh-ti-do”), sister to Chief Quistoh (Ditidaht of Port Renfrew) and originally betrothed to Chief

a·štido (“shee-ahsh-ti-do”), sister to Chief Quistoh (Ditidaht of Port Renfrew) and originally betrothed to Chief  isi·t (“klih-seet”), a casualty of the 1853 smallpox epidemic. James married Mary Ann George, daughter of Tsat-tsat-wha (Makah chief of Tatoosh) and Mei-ye-te-tidux (Ahousaht). In 1897 Jongie married Lizzie Parker, daughter of Wilson Parker and Babitsweyklub, two Makahs. James married his daughter Minnie to Chestoqua Peterson, the son of Peter Brown and nephew of Wha-laltl as sá buy, the Makah chief whose murder in 1861 perpetuated the conflict with the Elwhas.8

isi·t (“klih-seet”), a casualty of the 1853 smallpox epidemic. James married Mary Ann George, daughter of Tsat-tsat-wha (Makah chief of Tatoosh) and Mei-ye-te-tidux (Ahousaht). In 1897 Jongie married Lizzie Parker, daughter of Wilson Parker and Babitsweyklub, two Makahs. James married his daughter Minnie to Chestoqua Peterson, the son of Peter Brown and nephew of Wha-laltl as sá buy, the Makah chief whose murder in 1861 perpetuated the conflict with the Elwhas.8

Claplanhoos first appear in the documentary historical record during the negotiations of the 1855 Treaty of Neah Bay with Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens. Early in the treaty council, a Neah Bay chief named Klah-pe at hoo (John Claplanhoo) spoke about his continuing sadness at the death of his brother, Halicks—whom he identified as the third-highest chief—from smallpox.9 After Halicks died, his chiefly position, titles, and other property passed on to his brother. But John also inherited his brother’s responsibilities. This meant that during the treaty negotiations, a distraught John still focused on what his people needed: access to customary marine waters, whales, seals, and fish.

To varying degrees, all three Claplanhoo chiefs during the post-treaty decades engaged new opportunities—schools, local and global markets, influential whites, and non-Native technologies—that accompanied settler-colonialism in the region. Yet they continued to participate in cultural practices ranging from lengthy potlatches to ritual preparations for customary hunting and fishing practices. Other Makahs also succeeded during this period; the Claplanhoos were not unique among their community. These accomplishments, tracked through archival and oral sources, reveal that the People of the Cape combined customary practices with new opportunities to attain high standards of living. Their participation in the expanding settler-colonial world supported their ability to continue forging a unique Makah identity and to resist the cultural assault of federal assimilation policies.

However, Makahs of the second half of the nineteenth century experienced enormous challenges that eventually undercut their success and autonomy. These challenges illustrate the limits of Makah agency in the face of unequal power held by non-Natives and historical trends outside their control.10 The People of the Cape and other indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast were not the only ones who hunted whales and seals. The growing number of non-Native whalers and sealers in local waters and the larger Pacific Ocean devastated marine species that provided for Makah subsistence and commercial economies. As more users overhunted Pacific resources, nation-states established conservation measures that legally privileged non-Natives over Natives and large over small operations. By the early twentieth century, Makah hunters of the sea found themselves excluded by law from once-lucrative fisheries then collapsing. Without the wealth and subsequent power Makahs accrued from customary marine harvests, the People of the Cape became susceptible to assimilation and poverty.

MAKAH WHALERS, 1850–1928

A customary practice for more than two thousand years, whaling had secured substantial wealth and power for the People of the Cape, but this situation began to change in the second half of the nineteenth century. As non-Native commercial whalers depleted Pacific stocks, Makahs experienced greater difficulty finding  i

i apuk (“chih-tuh-pook,” whales) in local waters. Subsequently, these indigenous whalers petitioned the federal government for new technologies to expand their Pacific hunting range. Yet Makahs received inconsistent levels of support for these requests, which prevented them from securing access to modern technologies for whaling to the degree that they wanted. Troubled by the dearth of whales migrating past Cape Flattery, Makahs suspended the active practice of whaling in 1928 until stocks rebounded at some point in the future.

apuk (“chih-tuh-pook,” whales) in local waters. Subsequently, these indigenous whalers petitioned the federal government for new technologies to expand their Pacific hunting range. Yet Makahs received inconsistent levels of support for these requests, which prevented them from securing access to modern technologies for whaling to the degree that they wanted. Troubled by the dearth of whales migrating past Cape Flattery, Makahs suspended the active practice of whaling in 1928 until stocks rebounded at some point in the future.

Whaling had always provided the foundation of the subsistence and commercial economies of the People of the Cape. They hunted many species of leviathans found in the Pacific. In 1852, they caught more than two dozen whales, which provided them with more than 60,000 gallons of oil, an amount exceeding the average take of a whaling ship returning to its northeastern port after a two-year voyage. A ship returning to New Bedford, Massachusetts, that same year carried an average number of 1,343 barrels, which represented between 40,290 and 47,005 gallons, of oil harvested during a two-year period.11 Makahs exchanged oil for a wide range of Native and non-Native goods, which made whalers wealthy individuals within the community and the ča·di· borderland. One Makah elder today recalls stories of his grandfather Hiškwi (“hish-kwee”), a Wa a

a (“wuh-uhch”) chief born in 1845 who had earned substantial wealth from whaling. When federal Indian agents in the late nineteenth century forced him to give up two of his three wives, Hiškwi provided these women with enough money to live in comfort for the rest of their lives.12 But overhunting by non-Natives in the Pacific Ocean eventually changed the fortunes of Makah whalers.

(“wuh-uhch”) chief born in 1845 who had earned substantial wealth from whaling. When federal Indian agents in the late nineteenth century forced him to give up two of his three wives, Hiškwi provided these women with enough money to live in comfort for the rest of their lives.12 But overhunting by non-Natives in the Pacific Ocean eventually changed the fortunes of Makah whalers.

Initially, the arrival of non-Native whalers to the Pacific brought further wealth to Makahs, much as maritime fur traders did. In the late eighteenth century, these outsiders sailed into the Pacific as they sought new hunting grounds, and their numbers grew rapidly. In 1787, the English whaler Amelia took the first sperm whale in the Pacific, and by 1791, Yankee whalers from Nantucket and New Bedford hunted in the ocean, too. Maritime historians sometimes aggrandize the role of white whalers, characterizing them as “part of the advance guard of civilization” because they explored uncharted seas and brought unknown areas and peoples—unknown at least to the United States and Europe—into global markets. But this assessment becomes complicated when we consider the role of indigenous peoples in these pursuits. The Butterworth, one of the earliest ships to return to England after trading along the Northwest Coast and generally credited for commencing North Pacific whaling, brought back about twenty thousand gallons of whale oil in 1795. The Butterworth’s crew, however, did not procure this oil from whales they had hunted; they had purchased it from indigenous whalers in the ča·di· borderland. By the early nineteenth century, a few whaling vessels from England and New England told port authorities that they were bound for the Northwest Coast to hunt leviathans.13 After making the long trip around Cape Horn, these ships needed fresh provisions, which encouraged them to interact with indigenous peoples along the Northwest Coast. Savvy Native traders also offered whale oil to these outsiders, meaning that perhaps indigenous whalers harvested and processed a substantial portion of oil landed in Atlantic ports by these ships.

After the War of 1812, the Pacific whaling industry grew as the fleet expanded and engaged new ports along the northeastern seaboard of the United States. Whalers targeted sperm whales because of the high quality of their oil, which was used for illumination. The “golden age” of whaling began in 1835 with the taking of the first right whale—called this because it was the “right” whale to hunt due to its high oil content and ease of capture—off the Northwest Coast above 50°N latitude. This coincided with a booming demand for whale oil lubricants used by textile factories filled with power looms. In 1851 alone, one factory in Lowell, Massachusetts, used 6,772 gallons of whale oil, which represented the harvest of three sperm whales.14 By 1846, more than seven hundred barks, brigs, and schooners from US ports whaled in the Pacific, most of them cruising right-whaling grounds in the Gulf of Alaska and off Kamchatka and the Kuril Islands.15

Whaling vessels often came into the ča·di· borderland, where they interacted with Makahs and other indigenous peoples. Whalers anchored at Neah Bay to procure fresh provisions and whale oil from the People of the Cape. But because of the legacy of violent encounters during the maritime fur trade, some feared Makahs and neighboring communities. In September 1843, the Caroline (US) and Réunion (French) fled Cape Flattery despite a brief and friendly encounter. After whaling together off Alaska’s Kodiak Island, the two vessels approached the cape to seek provisions and new hunting grounds. Seven canoes of Makahs greeted them, offering fresh fish and whale oil for sale. An English-speaking chief tried to persuade them to come into Neah Bay where they could sojourn for several weeks until whales migrating north came into the strait. But Captain Daniel McKenzie of the Caroline “d[id] not like the appearance of things” and feared a trap. Over the strenuous objections of the French captain, whose crew needed provisions, McKenzie departed the area and sailed for San Francisco. Fearing to anchor alone at Neah Bay, the Réunion followed the Caroline south. Although anxiety marked this encounter, enough whaling ships visited Neah Bay that Makahs knew what crews needed and wanted.16

Some vessels came into the Strait of Juan de Fuca looking for new whaling grounds or for locations to establish shore whaling operations. In the fall of 1847, the General Teste, a French whaler from Le Havre, cruised into the strait to hunt in the Gulf of Georgia and northern Puget Sound, sixty to eighty miles east of Cape Flattery. But the General Teste did not do well—the crew killed only one whale and lost even that one—and they had left by early 1848. Non-Native shore whaling operations in this region also faltered in the beginning. From 1867 to 1871, just under a dozen companies—all operating from shore stations on the British side of the border—formed and collapsed, and none lasted longer than two seasons. They suffered from stormy weather, lack of proper equipment, low oil prices, vessel losses, and perhaps unskilled workers. In the dense fogs characteristic to the area, these nonlocal hunters often lost slain whales, which drifted off or sank. The most successful venture captured only nineteen whales and produced about thirty-three thousand gallons of oil in 1869, about half of what Makahs had processed a decade earlier.17

As with similar expansions of the settler-colonial world into the region, Makahs engaged in the non-Native whaling industry. Along with other Pacific peoples, some, such as  i·tap (“kee-tuhp,” David Fischer) and General Jackson, labored on non-Native whaling ships and explored the larger world. Shipping out of Neah Bay in the 1850s, Fischer joined cruises lasting years in length and even traveled as far abroad as Africa.18 A few indigenous borderlanders also labored at local shore whaling stations, although white operators ignored the whaling expertise of these people, limiting them to tasks such as towing carcasses to shore and stripping the flesh and blubber. Native women lived with some non-Native men working at the shore stations and probably contributed by rendering blubber into oil, a customary activity back in their home villages. Indigenous whalers often picked up the prey struck but lost in the fog by their non-Native counterparts. Although whites complained in local papers that Indians “appropriated to their own use” carcasses belonging to shore whaling operations, Natives probably sold to traders oil processed from these “losses.”19 Through this wage work and by harvesting drift whales that had escaped from white shore whalers, Natives continued to mark historical and cultural places in the ča·di· borderland as theirs.20

i·tap (“kee-tuhp,” David Fischer) and General Jackson, labored on non-Native whaling ships and explored the larger world. Shipping out of Neah Bay in the 1850s, Fischer joined cruises lasting years in length and even traveled as far abroad as Africa.18 A few indigenous borderlanders also labored at local shore whaling stations, although white operators ignored the whaling expertise of these people, limiting them to tasks such as towing carcasses to shore and stripping the flesh and blubber. Native women lived with some non-Native men working at the shore stations and probably contributed by rendering blubber into oil, a customary activity back in their home villages. Indigenous whalers often picked up the prey struck but lost in the fog by their non-Native counterparts. Although whites complained in local papers that Indians “appropriated to their own use” carcasses belonging to shore whaling operations, Natives probably sold to traders oil processed from these “losses.”19 Through this wage work and by harvesting drift whales that had escaped from white shore whalers, Natives continued to mark historical and cultural places in the ča·di· borderland as theirs.20

The eastern Pacific whale fisheries followed a similar pattern of declining returns as non-local, commercial whalers depleted a given stock within a decade and then moved on to another species. During the 1840s, whalers targeted right whales in the North Pacific, and by the 1850s, returns had plummeted to a quarter of those from the previous decade. These whalers often lost many they harpooned. In 1841, the Superior struck fifty-eight whales along the Northwest Coast but only recovered twenty-six, noting that another five sank before retrieval. After examining numerous logs from whaling’s golden age, one historian concluded that the death of unrecovered whales was high because nearly every logbook made references to encountering the carcasses of right whales that had died from harpoon strikes.21 After discovering bowhead grounds in the Bering Sea in 1849, whalers shifted to this baleen whale, and by 1865, they had reduced the bow-head population by more than half. Due to decreasing numbers of bowheads—and the actions of the Shenandoah, a Southern privateer steamship that burned thirty-four Yankee whaling vessels in the Bering Sea toward the end of the Civil War—non-Native whalers shifted their focus to hunting gray whales in calving grounds off Baja California. Intense commercial whaling also caused this fishery to collapse, and the gray whale population plummeted from a high of twenty-four thousand at the beginning of the century to two thousand by the 1880s.22

Overhunting of Pacific whale populations caused the New England whaling industry to wither and die during the 1870s. Decades of fluctuating prices for oil and baleen made it difficult for investors to sustain steady returns. Profitable years resulted in the growth of the fleet and new ports, which in subsequent years flooded markets with whale products and drove prices down. This situation meant that voyages were too expensive for the meager returns. Once lasting just two years, cruises in the 1870s stretched from four to six years, yet amounts of oil and baleen decreased. Longer voyages required a more substantial outfitting of vessels, an expense that grew out of proportion with profits. Only the Northern Pacific and Arctic fisheries—“where disasters were the rule and immunity from them the exception”—retained any hope of profit. The whaling fleet in the Arctic suffered a catastrophe in 1871, when ice crushed thirty-four ships. The financial losses from this numbered in the millions of dollars. More than a thousand survivors eventually made it to Honolulu, where they languished while seeking employment in a dwindling industry. As whaling profits plummeted, the output from the nation’s petroleum wells increased, providing a plentiful, high-quality, and cheap alternative to whale oil for lighting and lubricants.23

For New England laborers and investors, other industries beckoned. By the 1870s, whaling captains, experienced sailors, and “green hands” were earning little; crewmember income averaged between $3 and $7 a month. These laborers felt that “a strenuous and dangerous voyage of a year yielded not a penny besides the food.” They found better wages in the booming manufacturing industry of the Northeast. Pacific Rim gold discoveries encouraged desertions as whaling became less profitable. Sailors—and even captains and officers—joined whaling ships simply to get to the region. Profits also diminished for shipowners. After the 1871 catastrophe in the Arctic, insurance premiums rose to “almost prohibitive heights.” The transition from sail-powered ships to more successful steam-powered vessels was too expensive for many who had already invested their capital in sailing ships.24

Although the end of the industry in the Northeast was not the end of US whaling, the demise of Yankee whaling in the 1870s affected the People of the Cape, illustrating just one way that larger trends undercut Makah opportunities. After the Civil War, San Francisco grew into the leading port for whalers, and competition from this new center of the industry contributed to the waning influence of Northeastern ports, whose vessels had once frequented the Cape Flattery villages. By 1883, San Francisco had whale oil refineries and sperm candle works. Instead of shipping oil and other whale products around Cape Horn—an arduous and long voyage, at best—merchants used new transcontinental railroads to transport commodities east. By 1893, thirty-three whaling ships were based out of the Pacific port, and twenty-two of these were steamers. Instead of anchoring at Neah Bay to resupply, steamships put in at other ports, which had access to abundant coal. With no Yankee whalers stopping at Cape Flattery and the new steam-powered whaling fleet bypassing Makah villages, the People of the Cape lost an important market for whale oil. The shift to expensive floating factory ships at the turn of the century moved whaling even farther from the coast and indigenous whalers. Twentieth-century whaling focused less on whale oil, a commodity easily provided by Makahs, and more on goods indigenous peoples could not provide, such as fertilizers, bone meal, animal fodder, glue, cosmetics, and other products requiring expensive industrial processes.25

Most important, the overall decline of whales in the Pacific affected Makah whalers such as John Claplanhoo. Known as Captain John by whites, this patriarch was a whaling chief. But he seemed to doubt his whaling ability when he measured his kills against those of other hunters. To bolster his hunting prowess and prove his lineage as a whaler, he made theatrical shows of his ancestral “whale medicine,” pieces of dead whales and a bone of the  i

i i·ktu·yak (“hih-heek-too-yuhk”), a sea horse–like snake that stuns whales with lightning. According to Northwest Coast legends, Thunderbird uses the

i·ktu·yak (“hih-heek-too-yuhk”), a sea horse–like snake that stuns whales with lightning. According to Northwest Coast legends, Thunderbird uses the  i

i i·ktu·yak when he comes down from his alpine nest to hunt whales. When John had trouble hunting in the mid-1860s, he underwent extra ritual preparations, including fasting, sleep deprivation, and bathing in saltwater with his whale medicine.26

i·ktu·yak when he comes down from his alpine nest to hunt whales. When John had trouble hunting in the mid-1860s, he underwent extra ritual preparations, including fasting, sleep deprivation, and bathing in saltwater with his whale medicine.26

Others who noticed the declining number of whales attributed it to various causes. In 1858, Makahs complained to an Indian agent that they objected to the government lighthouse at Tatoosh Island not only because it was built on land that belonged to the tribal nation but also because “it keeps the whales from coming as usual.” Several decades later, Lighthouse Jim (Makah) joked to James Swan that they had a harder time catching  i

i apuk “as [they] now drink coffee at each breakfast before going out as the whales smell their breath.” However, John’s poor whaling skills, the new lighthouse, and Lighthouse Jim’s coffee breath probably did not make it harder to catch whales. Instead, their experiences reflected the changing ecology of the Pacific, namely the removal of vast numbers of leviathans by non-local commercial whalers.27

apuk “as [they] now drink coffee at each breakfast before going out as the whales smell their breath.” However, John’s poor whaling skills, the new lighthouse, and Lighthouse Jim’s coffee breath probably did not make it harder to catch whales. Instead, their experiences reflected the changing ecology of the Pacific, namely the removal of vast numbers of leviathans by non-local commercial whalers.27

Despite the increasing difficulty of securing whales throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, whaling remained important to the People of the Cape. The continued prominence of whalers among tribal leadership indicates that these chiefs must have provided tangible benefits. John Claplanhoo maintained his position as a recognized leader of his people, and detailed census records of the 1860s show his longhouse as one of the largest. From 1861 to 1865, average longhouse populations fell from 18 to 12.6, whereas the Claplanhoo longhouse grew from 22 to 24 individuals. In the first American-style election held on the reservation, the residents of Neah Bay chose John as one of their four chiefs, who, in turn, elected him tribal chairman in 1879. Although Claplanhoo drew his profits from a variety of economic activities—his slaves cut wood, cleared land, and did chores for the Neah Bay Agency; he fished; and he engaged in regular trade with Native villages and colonial towns—he continued to value his identity as a whaler. In 1878, during a grand ceremony, he took the name Łutka·bałid (“lthoot-kah-buh-lthihd,” Thunder on the Ocean), which tied him to his family’s whaling heritage.28

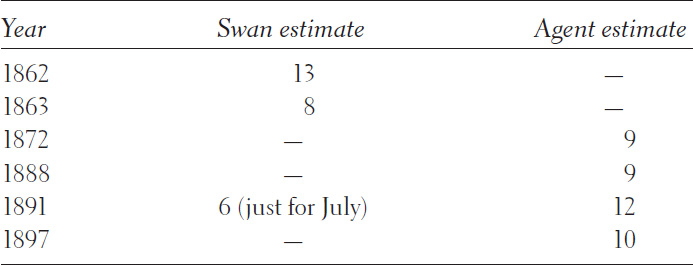

Whaling statistics from the second half of the nineteenth century are difficult to ascertain because no one kept complete returns for the entire community, yet available evidence indicates that Makahs regularly landed around a dozen whales each year. Based on statistics provided by the whaling chief Wha-laltl as sá buy (Swell) in 1859, Swan noted that thirty canoes of Makah whalers harvested thirteen whales that year and produced about thirty thousand gallons of oil.29 During his tenure at Neah Bay as the agency teacher, Swan noted occasions when Makahs hunted whales; but these numbers were less accurate than the 1859 statistics provided by Wha-laltl because Swan could not be everywhere on the reservation at all times. He never heard of some hunts—especially those from the coastal villages of Wa a

a ,

,  u·yas, and Ozette—and there were probably times when he did not report whaling about which he did hear. Yet some of Swan’s numbers are close to those reported by Wha-laltl, as are those reported by Indian agents who also occasionally noted the number of whales taken that year. Agents’ numbers are lower than they actually were because they, too, were not in a position to report every hunt.

u·yas, and Ozette—and there were probably times when he did not report whaling about which he did hear. Yet some of Swan’s numbers are close to those reported by Wha-laltl, as are those reported by Indian agents who also occasionally noted the number of whales taken that year. Agents’ numbers are lower than they actually were because they, too, were not in a position to report every hunt.

These whaling returns compared favorably to contemporaneous non-Native operations along the West Coast. In 1872, Makahs hunting in canoes produced an estimated 20,700 gallons of oil from the nine whales the agent reported among this community of 604 individuals. Two years earlier, San Francisco, a growing city with nearly 150,000 people, landed 4,013 barrels (or about 130,423 gallons) of whale oil from six vessels that identified the city as their homeport. This oil resulted from four-to-six-year cruises in the Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean, and 1870 saw one of the highest oil returns recorded by the city’s port officials until the advent of steam-powered whaling ships later that century. When we consider that this non-Native oil came from leviathans harvested during voyages lasting several years, this statistic represents an average of 27,590 gallons per year, an amount not much higher than what Makahs produced in 1872.30

Table 1. Snapshot of Makah whaling returns during the second half of the nineteenth century

Sources: From Swan’s Diaries, 5–7, 55, Swan Papers, 1833–1909; E. M. Gibson, Agent Report, ARCIA (1873), 308; W. L. Powell, Agent Report, ARCIA (1888), 225; John P. McGlinn, Agent Report, ARCIA (1891), 448; Samuel G. Morse, Agent Report, ARCIA (1897), 292.

As whale oil returns dwindled at similarly sized white operations, Makah harvests remained high during the last two decades of the nineteenth century. In 1888, Makahs again harvested at least nine whales, which produced approximately 20,700 gallons of oil. In comparison, a shore whaling station occupied by Portuguese at San Simeon Bay, California, took seven gray and humpback whales in 1888 and the same amount in the following year. From these whales, this station produced only 180 and 260 barrels (or 5,850 and 8,450 gallons) of oil, respectively. With twenty-one men and nine boats at the time, this operation was “one of the principal whaling stations on the Pacific Coast” and had operated since 1865.31

Comparing the oil returns of Makah whalers to a similar whaling operation along the coast of California reveals two important conclusions. First, during a period when leviathans were “disappearing from the Pacific Ocean,” as reported by the New York Times, Makah whalers harvested more whales than non-Natives engaged in the same industry. Second, Makah women were more then twice as efficient when it came to processing oil—either that or Makahs hunted larger specimens than their Portuguese counterparts in California did. The fact that the People of the Cape on average rendered 2,300 gallons of oil from each whale is significant. This number might appear unusually high because scholars commonly assume that commercial whalers in the nineteenth century harvested between 20 and 30 barrels (anywhere from 600 to 1,050 gallons) of oil per whale. Butchering a whale on the high seas was dangerous because it produced a large amount of blood and oil, making the deck of a whaling vessel slick. Sailors slipped in the mess and sometimes ended up overboard in waters filled with sharks drawn to the carnage. Add to this the way large waves or storms would rock a ship, and it is easy to see that whalers probably sacrificed thoroughness for speed when it came to butchering a whale, which could take many hours or even days. When compared to Long Island shore whaling stations of the eighteenth century, Makah returns appear reasonable. Lord Cornbury, the British governor of New York and New Jersey (1702–8), reported in 1708 that two-year-old whales often yielded nearly 2,000 gallons of oil, with the largest specimens resulting in more than 3,000 gallons. Industrial whaling of the early twentieth century sometimes resulted in yields of 7,500 gallons of oil from the blubber of large whales.32

Despite their success as whalers, the People of the Cape could do little about the impact of modern whaling on sea mammal populations in the Pacific. Claplanhoo oral histories recall that 1909 marked the last whale hunt completed by a family member. Jongie, grandson to John Claplanhoo, killed this whale and added the one-hundred-and-forty-second notch to the harpoon that his forebears had used for four generations. Makahs took the occasional whale during the second decade of the twentieth century, but by this time, they rarely saw  i

i apuk in local waters. A whale sighting resulted in tremendous excitement and the immediate launch of whaling canoes. In 1928, nineteen years before non-Natives decided to suspend the hunt of gray whales, concern over the dearth of whales caused the tribal nation to suspend the active practice of whaling until populations had rebounded. Makahs took their responsibilities to nonhuman kin such as whales seriously, and this tough decision made sense. To provide the youngest generation with the experience of welcoming a whale to Neah Bay, whalers held a final hunt. The tribal nation always intended to revive an active whaling practice at some point in the future.33

apuk in local waters. A whale sighting resulted in tremendous excitement and the immediate launch of whaling canoes. In 1928, nineteen years before non-Natives decided to suspend the hunt of gray whales, concern over the dearth of whales caused the tribal nation to suspend the active practice of whaling until populations had rebounded. Makahs took their responsibilities to nonhuman kin such as whales seriously, and this tough decision made sense. To provide the youngest generation with the experience of welcoming a whale to Neah Bay, whalers held a final hunt. The tribal nation always intended to revive an active whaling practice at some point in the future.33

Charles White harpooning a whale. The whale has already been harpooned; White is making a second thrust and has a sealskin float attached to the harpoon line. This is thought to be a photo of the hunt in 1928, the last one for more than seventy years. Photograph by Asahel Curtis, courtesy the Makah Cultural and Research Center, Neah Bay, WA.

Before deciding to suspend whaling, the People of the Cape looked to new technologies that would allow them to expand their hunting grounds deeper into the Pacific, much as non-Native commercial whalers were doing at the time. In 1862, John Claplanhoo spoke with Swan about the possibility of purchasing a schooner from a local trader. Already finding it more difficult to locate whales along the coast, John hoped to use the larger vessel to hunt far from the safety of the coast. In 1884, a hundred Makahs met in council with an Indian inspector and urged him to convince the government to provide them with a steamship so they could more easily haul in whales from the Pacific. Some of these individuals had been present at the 1855 treaty negotiations, and they recalled that Governor Stevens had promised to support tribal marine industries. By making these requests in the decades following the treaty, the People of the Cape attempted to hold the government responsible for its promises.34

Some officials supported Makah requests for modern vessels, despite federal efforts to transform all American Indians into farmers. In his annual reports for 1865 and 1867, Henry Webster, the Makah agent, forwarded the tribe’s requests to his superiors, as did agents Elkanah M. Gibson (1873) and Charles A. Huntington (1876). They questioned the department’s wisdom in sending agricultural implements to coastal peoples such as the Makah, who found the intended purpose of these tools nearly pointless. Instead, the People of the Cape fashioned them into fishhooks, blubber knives, and points for whaling lances.35 During the 1860s and 1870s, the Indian Affairs Department ignored Native entreaties for vessels. In the 1880s, however, the department agreed to finance the Makah request for a steamship due to a favorable review by an Indian inspector. Unfortunately, the final decision rested on the advice of the current Makah agent, Oliver Wood, who apparently thought that all American Indians, including those living on the Pacific Coast, should abandon fishing in favor of farming. Even though many Makahs were experienced deckhands aboard local steamships plying Northwest Coast waters, Wood considered the request unreasonable because a steamer would cost $8,000, plus the cost of fuel and wages for white crewmembers. If they had acquired either of these vessels earlier, Makah whalers could have possibly met the challenge of a dwindling number of whales migrating past Cape Flattery by expanding their hunting range farther into the Pacific.36 Instead, they spent more time seeking fewer whales that swam into coastal waters. In this way, a combination of environmental (non-Native overhunting) and policy (federal policies and assimilationist agents) factors outside their control curtailed a fundamental Makah practice.

Although customary whaling methods endured throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, the People of the Cape sought more efficient ways to hunt whales. In 1861, James Swan observed Peter Brown—an individual from a long line of whalers—use a rifle during a casual hunt. Eighteen years later, after seeing a mortar fired, older whalers expressed interest in acquiring one to use for whaling. When the opportunity presented itself, whaling crews hired powered ships to haul harpooned whales into Neah Bay. In 1905, two vessels, the Wyadda and the Lorne, witnessed a hunt and competed for the opportunity to bring in the carcass. The Makahs chose the Wyadda, a tugboat that pulled ships into or out of the strait. Because the federal government had failed to honor Makah requests for a modern vessel, the People of the Cape turned to local ships to assist in their hunts.37 Using tugboats to tow whales ashore, employing rifles to hunt, and expressing interest in other modern gear did not dilute the customary practice of whaling. Nor did these modifications and participation in local and global markets make these hunters any less Makah. By engaging non-Native tools and opportunities during the third quarter of the nineteenth century, Makah whalers continued what they had been doing for generations—adapting to a changing world in ways that maintained their wealth and distinct identity as the People of the Cape.

MAKAH PELAGIC SEALING, 1871–1897

When Makah families such as the Claplanhoos combined customary practices with modern opportunities and technology in the case of pelagic (oceanic) sealing, they accumulated considerable wealth.38 This strategy enabled them to better resist assimilation and to control both their marine space and reservation lands. Not only did Makah hunters labor on vessels owned by non-Natives, but they also became important investors in this extractive industry, purchasing expensive, modern schooners that the federal government would not. Sealing from ships allowed this tribal nation to expand Makah marine space substantially as they hunted pinnipeds in local waters, to the south off the coast of California, to the north in the Bering Sea, and eastward to Japan. The environmental cost of this industry—in which Makahs were particularly successful hunters—prompted the United States to focus the nation’s first international conservation efforts on fur seals, the target of pelagic sealers. At the end of the nineteenth century, Congress passed laws that ended commercial pelagic sealing for Makahs and other laborers while allowing well-capitalized and politically connected non-Native corporations to continue hunting. When nations grappled with conservation issues on the international stage, diplomats not only shut out indigenous investors from a profitable industry but also denied them compensation opportunities. Wealthy Makah entrepreneurs found themselves shackled to the timeless stereotype of the Native subsistence hunter. The US prohibition on pelagic sealing reversed the fortunes of the People of the Cape, transforming many from wealth to poverty as they entered the twentieth century.

Like his father, John, James Claplanhoo took advantage of modern opportunities to secure and strengthen his leadership position among Makahs. Although James whaled, his financial success in the fourth quarter of the nineteenth century came from sealing rather than whaling.39 By the 1870s, the skins of  iładu·s (“kih-lthuh-doos,” fur seals)—a sea mammal long hunted by Makahs for their flesh, hide, and oil—had become a valuable commodity. Skins from the North Pacific ended up in London, where furriers turned them into stylish, ebony sealskin coats worn by the likes of wealthy, urban women and Mark Twain. An early twentieth-century reference book for English women called a sealskin coat a “precious possession” and carefully detailed how to select one, which usually cost around £200.40 By 1871, Makahs were trading sealskins for clothing, flour, and other items. London merchants prized skins from fur seals caught off Cape Flattery; these skins garnered the best prices in the 1870s. As local traders on both sides of the international border competed for sealskins, Makahs began demanding cash. In 1873, James and about 150 Makah hunters together earned over $10,000 (nearly $200,000 today) selling 1,500 skins from seals they had taken up to forty miles offshore during the first five months of the year. A year later, they sold twice the amount of sealskins and made $15,000.41

iładu·s (“kih-lthuh-doos,” fur seals)—a sea mammal long hunted by Makahs for their flesh, hide, and oil—had become a valuable commodity. Skins from the North Pacific ended up in London, where furriers turned them into stylish, ebony sealskin coats worn by the likes of wealthy, urban women and Mark Twain. An early twentieth-century reference book for English women called a sealskin coat a “precious possession” and carefully detailed how to select one, which usually cost around £200.40 By 1871, Makahs were trading sealskins for clothing, flour, and other items. London merchants prized skins from fur seals caught off Cape Flattery; these skins garnered the best prices in the 1870s. As local traders on both sides of the international border competed for sealskins, Makahs began demanding cash. In 1873, James and about 150 Makah hunters together earned over $10,000 (nearly $200,000 today) selling 1,500 skins from seals they had taken up to forty miles offshore during the first five months of the year. A year later, they sold twice the amount of sealskins and made $15,000.41

By the late 1870s, Makah sealers began accumulating substantial cash by joining crews aboard white-owned schooners based out of Victoria, Port Townsend, Seattle, and San Francisco. Nuu-chah-nulths from the West Coast of Vancouver Island had been sealing from schooners for more than a decade before this. For one-third of the catch, schooners took sealers and their canoes and gear out to sea for weeklong voyages. By the mid-1880s, indigenous hunters could make almost twice as much in one sealing season as non-Native laborers in other industries earned in a year because of the high price of sealskins. Some chiefs earned fees for brokering labor agreements with ship captains, traders, and Indian agents. A local trader agreed to pay Lighthouse Jim $30 at the end of the sealing season if he persuaded his friends to sell their skins to him. Occasionally, a sealer’s wife joined the crew as cook and skinner. Makah women also processed seal blubber into oil—around 1,500 gallons each season—reserving the cleanest oil for consumption. In 1880, the Makah-organized Neah Bay Fur Sealing Company chartered the Lottie, a Port Townsend schooner, and made over $20,000 during the four-month season. Competition for sealskins enabled skilled hunters to command high values for their catches and choose the captains and vessels for which they would hunt.42

The People of the Cape understood the benefits of schooner ownership. James Claplanhoo was one of the first Native borderlanders to acquire one of these vessels. After spending the previous year considering several, James purchased the thirty-one-ton Lottie from a local trader at the beginning of 1886. He paid $1,200 cash, some of which he borrowed from Ditidaht relatives across the Strait of Juan de Fuca, with another $600 due at the end of the sealing season. Crewing his new ship with Makah sealers, James employed it in the spring hunt along the Washington and Vancouver Island coasts. The Lottie transported canoes to sealing grounds up to one hundred miles offshore. At night, the sealers ate and slept on the Lottie, which allowed them to stay out on cruises for a week or longer. After purchasing the schooner, James increased his profits from commercial pelagic sealing. That year Makah sealers earned $16,000; although the Indian agent did not record the division of profits, the Claplanhoos and the hunters they took with them on the Lottie probably cornered a large share of these profits.43

Nuu-chah-nulth pelagic sealers aboard the Canadian schooner Favorite, 1894. For one-third of the catch, schooner owners took Indian sealers aboard their vessels to hunt fur seals in the Pacific, from California to the Bering Sea. This photograph was taken in the Bering Sea. Photograph by Stefan Claesson. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association/Department of Commerce.

Other Makahs also invested in pelagic sealing. A year before James bought the Lottie, the high-ranking chief Peter Brown purchased the Letitia for $1,000. In 1886, the same year that James acquired his first schooner, Klahoowik and Haspooey bought the twenty-six-ton Sierra from three San Franciscans for $1,500. A month later, Lighthouse Jim paid over $1,000 for the C. C. Perkins. These owners recruited Makahs and other Natives from neighboring villages on both sides of the strait to work their vessels, and occasionally they hired white captains and sailors. By 1887, five Makah-owned schooners engaged in sealing out of Neah Bay, and that number more than doubled by 1893. As the People of the Cape integrated schooners more deeply in their society, they made toy schooners for boys so they could envision themselves growing up to become ship captains and owners.44

In the 1890s, local whites mistakenly assumed that the motivation—and perhaps even funds—for Makah schooner ownership came from the federal government, not entrepreneurial Native families. A popular history of the time surmised that “somehow the proprietorship of several well known sealing vessels has come to them without any effort on their part; it was something of a parental care on the part of a thoughtful government.”45 Yet the archival record and oral histories prove that the People of the Cape acted on their own initiative when making capital investments in the North Pacific extractive industry of pelagic sealing. By working hard, taking risks, and pooling and investing money, Makah families—not a paternalistic or helpful government—made this possible. Like late nineteenth-century Cherokee farmers and ranchers who had “a passion for building family fortunes in business ventures,” Makah schooner owners sought new entrepreneurial opportunity to build their own fortunes. Like Navajo coalminers and weavers, Menominee loggers, and Tsimshian, Tlingit, and Haida fishers and cannery workers, these Makahs exemplify yet another way that indigenous peoples situated their industries in a capitalist marketplace, even operating within capitalist modes of production, while adhering to local values to create unique economic accommodations and outcomes.46

By employing schooners as floating bases to hunt seals, the People of the Cape not only earned larger profits but expanded their hunting range. Whereas canoes alone had once limited Makahs to hunting pinnipeds within thirty miles of Cape Flattery and in the strait, schooners allowed them to extend their spring coastal sealing from the mouth of the Columbia River to the northern tip of Vancouver Island. Makah sealing also expanded into the North Pacific. In the summer of 1887, James took the Lottie farther north, for cruises in the Bering Sea made the greatest profits. Hunters could harvest many more seals, and these skins fetched high prices on the London market. The Bering Sea voyages were lucrative, netting James $3,600 in profits during the 1889 season in the Bering Sea. In following years, the Lottie’s profits from North Pacific pelagic sealing brought the Claplanhoos between $7,000 and $8,000 annually (about $180,000 to $200,000 today).47

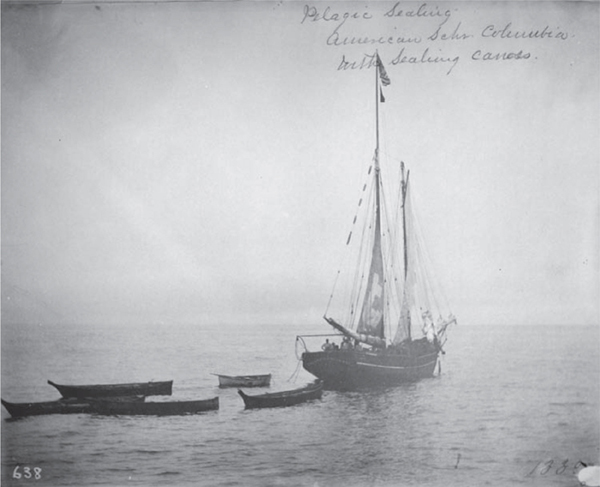

Makah sealing schooner Columbia, with sealing canoes, 1894. Chestoqua Peterson (Makah) purchased this schooner on October 22, 1893, and took it sealing in the Bering Sea. Photograph by Stefan Claesson, 1894. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association/Department of Commerce.

With these profits, James expanded his investment and purchased a small fleet of vessels. After the 1891 sealing season, he began shopping around for a second schooner, traveling to San Francisco aboard a steamer to inspect vessels. He eventually commissioned a boat builder in Seattle to construct the larger, forty-two-ton Deeahks, which he named after an ancestor and sailed back to Neah Bay in January 1893. That year, he also purchased the Emmett Felitz, a thirty-ton vessel. And sometime between 1887 and 1893, he bought the fifteen-ton Puritan. His son Jongie commissioned a new schooner for $2,500 at the beginning of 1897. James also maintained his vessels regularly. During the stormy winter months, he paid for sheltered moorage at Scow Bay near Port Townsend. He had them repaired by non-Native carpenters in Hadlock, another Puget Sound port, and bought new sails for his ships. The Claplanhoos and other Makahs insured their vessels with local white merchants, such as Frank Bartlett, owner of one of Puget Sound’s largest mercantile establishments, and J. Katz, a German immigrant who had become a successful mercantilist.48

Although less well documented than shipbuilding, pelagic sealing also supported the canoe-building industry among Northwest Coast peoples because it generated a demand for medium-sized hunting canoes. Sealing required hundreds of canoes across the ča·di· borderland. Many of these saw hard use; frequently damaged and broken canoes needed constant replacement. In the 1890s, top-quality sealing canoes cost as much as $300. Financial benefits from this industry flowed to more than just the handful of chiefs who owned the growing fleet of sealing schooners.49

Makah pelagic sealers such as the Claplanhoos succeeded as entrepreneurial capitalists, an identity that scholars rarely ascribe to indigenous people. As one historian explains in her analysis of “rich Indians,” the gaze of historians is drawn away from enterprising Natives by the “seductive paradigm … [that] contrasts an egalitarian, spiritual, traditionalist Indian ethos with a competitive, materialistic, activist non-Indian ethos.”50 Like other successful investors, James diversified his assets in 1890 when he bought out the reservation trader for $3,000, purchasing his inventory and operation. A year later, he deposited $5,000 in Port Townsend’s Merchants Bank, where his money earned 6 percent interest. Some Makahs invested their sealing profits in other ventures, including Koba·li (“koh-bah-lee”), a “full-blooded Indian” who owned a hotel and had saved $1,000 to erect “a more pretentious building for accommodation of his guests,” as one surprised Makah agent reported. The financial actions of the People of the Cape were part of a larger indigenous engagement with settler-colonial economies in the region. Aboriginal entrepreneurs of British Columbia made important contributions to the emerging capitalist economy of the colony—then province—during the second half of the nineteenth century. They traveled from one village to the next, buying Native products such as furs, fish, and oil to exchange in Victoria for goods they would resell up the coast. Indigenous artists created works for sale in non-Native markets, and Indian-owned stores and sawmills dotted the Northwest Coast. The diversity and scale of these financial and commercial activities reveal that many indigenous peoples of the ča·di· borderland were important investors in North Pacific extractive industries. Bucking the stereotype, these American Indians were highly sophisticated venture capitalists.51

Although sealers such as James embraced certain elements of non-Native technology and business acumen, they did not abandon Makah hunting methods. Instead, they combined the best aspects of both to increase their success in a customary practice. Even in the dangerous and new waters of the Bering Sea, Makahs preferred using customary gear. As along the coast, they conducted the actual seal hunt from specially adapted canoes. Most used a double-headed harpoon that they hurled with both hands instead of noisier rifles or shotguns that scared away seals. They adapted the harpoon’s design, incorporating iron or sheet copper tips instead of mussel shells. The reservation’s blacksmith, hired by the Office of Indian Affairs to support the tribe’s agricultural pursuits, instead became busy in the weeks before the coastal sealing season, fashioning metal tips for spears, lances, and harpoons. Prominent sealers in the community continued using traditional gear during important ceremonies, thereby indicating their enduring cultural value. By employing traditionally designed gear, Makahs rarely lost seals they struck. Some men used guns to hunt seals, but only when they worked from white-owned schooners in the Bering Sea.52

Pelagic sealing in the late nineteenth century supported and complemented other Makah labor and industry. Based out of Neah Bay, the coastal sealing season typically began in mid-January and lasted until early June. Beginning in mid-May some years and usually lasting until early October, Makahs sealers and their vessels hunted in the Bering Sea.53 In the 1880s and 1890s, sealing was the most important occupation for Makah males. Chestoqua Peterson, a prominent Makah by birth and marriage—he had married James Claplanhoo’s daughter—told Swan that 112 Makah males had hunted seals during the coastal season in 1892. This represented about three-fourths of the community’s hunting-age males, who began sealing at the age of ten with their older male relatives and continued into their mid-sixties. Unlike whaling, sealing was not limited to high-status Makah men, so anyone with access to a canoe and hunting gear could participate. During the coastal hunting season that year, these sealers made $21,242 (over $500,000 today), a substantial injection of cash and goods to the reservation community.54 A smaller percentage of Makah men sealed in the Bering Sea, earning thousands of dollars more during the summer. Those not sealing in the Bering Sea often headed to regional salmon canneries to labor as fishers, earning in the early 1880s nearly $60 per month, which compared favorably to wages of a skilled tradesperson.55 Seeking to get the most from their investments, indigenous schooner owners chartered their vessels for other purposes when they were not sealing. Makah ships transported goods around Puget Sound, hauled lumber and dynamite, and salvaged shipwrecks. Lighthouse Jim even shipped cargo to Honolulu aboard his vessel, the C. C. Perkins. Makahs also made their schooners available for family and friends who traveled around the region, such as groups of hop pickers headed to fields south of Seattle. Part of a larger migration of seasonal indigenous laborers, Makah hop pickers headed into Puget Sound in late August, returning to Cape Flattery in mid-October. Like other indigenous workers of this period, Makahs blended seasonal labor opportunities and extended their maritime customary practices well into the era of assimilation.56 Makah families spent the profits from their labors on various goods and services, including potlatches, vessels, homes and housing material, clothing, food, and photographs.57

As with Pacific whaling, commercial hunting rapidly exacted a catastrophic toll on fur seal numbers. Native and non-Native hunters took pinnipeds from the Pribilof herd, a once-massive population that migrated along the Northwest Coast to their breeding grounds on the Pribilof Islands in the Bering Sea. After the United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867, various fur companies flocked to the Pribilofs the following year, slaughtering more than three hundred thousand seals on Saint Paul and Saint George Islands. Concerned that a continued free-for-all would wipe out the herd, Congress designated the islands a government reserve and restricted hunting to a single leaseholder. In 1870, the Alaska Commercial Company (ACC) agreed to pay the US government $500,000 each year for a twenty-year hunting lease, which allowed them to harvest 100,000 fur seals annually. This lucrative arrangement allowed the federal government to net $10 million during the lease period, while the company paid more than $22 million to company shareholders, many of whom were congressmen. During the lease period, ACC hunters clubbed dead an average of 98,823 seals each year in their rookeries. In 1890, Congress awarded the second twenty-year lease to the North America Commercial Company (NACC). Attempting to conserve the Pribilof herd, the Department of Treasury limited the annual quota of seals killed on land to 60,000. NACC employees harvested well below this number, normally taking between 12,000 and 30,000 seals any given year. In 1892 and 1893, the government limited them to 7,500 seals annually in an effort to relieve hunting pressure on the herd.58

Seal fishery, Saint Paul Island, 1895. During the nineteenth century, the Alaska Commercial Company and North American Commercial Company used Aleut wage labor to club and skin seals. Photograph by Stefan Claesson. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association/Department of Commerce.

Convinced that seals belonged to no one until caught, pelagic sealers plied the North Pacific and Bering Sea, taking their prey from the same Pribilof herd from which the ACC and NACC hunters harvested. During the Alaska Commercial Company’s lease from 1870 to 1889, pelagic sealers took 269,276 fur seals, for an average of just over 14,000 seals a year, a number substantially below the lessee’s catch. However, this situation reversed in the mid-1880s as more vessels hunted seals in the North Pacific. In 1883, three hunters aboard the American City of San Diego caught 900 seals in the Bering Sea, which inspired a geographic expansion of the pelagic industry.59 By the time the North American Commercial Company assumed the Pribilof lease in 1890, the catch at sea outnumbered the land harvest by nearly three to one. From 1890 to 1897, pelagic sealers took 364,203 fur seals (an annual average of 45,525), while the NACC land hunters caught only 135,976 (an annual average of 16,997). Employing shotguns, non-Native pelagic hunters lost from half to three-fifths of what they shot, a wasteful practice deplored by Makah hunters who largely kept to using spears. Osly, a Makah who had sealed in the Bering Sea three separate times on both white-owned and Makah-owned schooners, complained, “The white hunters who used guns in the Bering Sea were banging away at the seals sometimes all day long, and they would lose a great many of those that they had shot. I do not think that they brought to the schooner one-half of those that they killed.” More concerning for conservationists, 75 to 80 percent of the pelagic catch consisted of breeding females, which undercut the ability of the Pribilof herd to sustain its numbers. When considering the additional loss of unborn pups and nursing ones that starved to death after the loss of the mother, pelagic sealing resulted in the loss of nearly two million seals from 1868 to 1897. Hunting pressure at sea and in the terrestrial breeding grounds triggered the collapse of the fur seal population.60

Among the first to notice reduced seal numbers in coastal waters, the People of the Cape went farther out seeking seals, which brought them into the ocean where sudden storms could capsize canoes or push them even farther away from home. Seven Makah men died at sea in 1875, and in 1881, on his way from Port Townsend to Honolulu, Captain Rufus Calhoun picked up two exhausted Makahs and their canoe more than fifty miles west of Cape Flattery. The 1883 season appeared particularly dangerous—“West Coast” Indians from Vancouver Island reported that “between 40 and 50 men of the different tribes, who ventured too far out to sea in their frail canoes, in search of seals, have been overtaken by gales and perished.” Although maritime accidents were not uncommon, schooner ownership enabled sealers to expand their customary activity from overhunted local waters to the greater North Pacific and into the Bering Sea with relative safety.61

Makah hunters faced an even greater obstacle: seal conservation backed by the power of the state and the London fur industry. As pelagic sealers, Makah hunters and shipowners such as the Claplanhoos found themselves on the losing side of a diplomatic struggle over the Pribilof seal herd. When he began investing in schooners in 1886, James Claplanhoo confronted Treasury Department officials keen on discouraging pelagic sealing in the Bering Sea. That year, he asked for permission to take the Lottie to Alaska to hunt sea otters and seals. The acting secretary of the Treasury replied that his department would not authorize any sealing permits for anyone other than the leaseholder of the Pribilofs, the Alaska Commercial Company, so James did not take his schooner into the Bering Sea. Fearing that they were getting cut out of the more lucrative hunting grounds in Alaskan waters, he and other Makahs repeated the request the following year. When federal officials neglected to reply, James took his schooner to the Bering Sea that summer, thereby expanding Makah marine space.62 Makahs did not extend ownership or control over these far northern waters as they did with more local waters off Cape Flattery. Instead, they began to make this space “theirs” through the shared experience of labor. For many Makah men in the late nineteenth century, sealing in the Bering Sea became an important part of their marine identity.

The People of the Cape brought their vessels into the Bering Sea at the same time that the federal government attempted to make the North Pacific into a more “legible” space. States attempt to arrange populations and resources in ways that simplify functions such as taxation, conscription, and order.63 From the perspective of the US government administering the District of Alaska, the most orderly and profitable way to benefit from the seal catch was by leasing to a single corporation the rights to hunt fur seals on the Pribilof Islands. Enforcing licensing fees on more than a hundred individually owned vessels and collecting taxes on the sale of skins from these ships was nearly impossible for any single nation-state. Many of the shipowners and individual hunters were not even US citizens—they instead hailed from Russia, Japan, and, most especially, Canada. When shipowners found any one nation’s licensing fees or hunting restrictions too onerous, they simply registered their vessel in another country.64 Schooner captains had numerous places in the North Pacific—many not even in the United States—where they could dock to sell their skins. From the view of US officials, pelagic sealing was anything but orderly, and it threatened the profitability of a lucrative national resource.

To curb the depredations on the American herd by foreign sealers, US Revenue cutters stopped twenty Canadian schooners from 1886 to 1890. They turned five foreign vessels out of the Bering Sea and confiscated the rest. Masters and mates of captured ships were imprisoned and fined, while the hunters were set “adrift several hundred miles from homes, without food or shelter,” as one contemporary commentator noted.65 Harry Guillod, the Indian agent for the West Coast Agency on Vancouver Island, detailed the difficulties Nuu-chah-nulth hunters experienced after US Revenue cutters seized the W. P. Layward in the Bering Sea: “These Indians suffered exceptional hardship having to find their way home from Sitka by canoe, it taking them 19 days to Port Simpson where they parted with their canoes for provisions also personal property, being there 26 days finally working their passage to Victoria on the Boscowitz. They lost their sealing gear and everything they had with them.” The US Treasury Department auctioned some of the seized vessels, such as the Anna Beck, a Victoria schooner that Chestoqua Peterson, the son of Peter Brown and husband to James Claplanhoo’s daughter, bought and renamed the James G. Swan. The US confiscations of Canadian vessels triggered a twenty-year-long diplomatic struggle between the United States and Great Britain—and eventually Japan and Russia, two other sealing nations—over the Pribilof herd.66

The US Revenue cutters also targeted Makah vessels in the Bering Sea. Narrowly escaping the cutters in early July 1889, Claplanhoo’s Lottie stayed in Alaskan waters for the summer and returned to Neah Bay at the end of August with 600 sealskins for a profit of $3,600. Peterson’s newly purchased James G. Swan was not as lucky; the Revenue cutter Rush seized it with 190 sealskins at the end of July. Fearing that the loss of the schooner and the summer’s returns would be a great hardship, Peterson pled ignorance of the law, arguing that he believed that the Revenue cutters had been in the Bering Sea to protect US schooners from foreign competitors.67 In previous years, the few Euro-American-owned vessels the Revenue cutters had seized had been either released or cleared of all charges by Treasury officials, a fact that infuriated Canadian sealers. At the urging of W. L. Powell, the Indian agent at Neah Bay, the commissioner of Indian affairs asked the attorney general’s office to provide legal protection to the schooner’s owner and Makah crew. But the Office of the Attorney General refused to offer them legal protection. Unlike Euro-American owners of vessels, Makah schooner owners suffered prosecution from the federal government.68

Peterson then hired James Swan, after whom he had named the schooner, as his attorney to help settle the case with the government. Swan petitioned the secretary of the Treasury on Peterson’s behalf, but the department declined to intervene in the case. When Judge Cornelius Hanford of the US district court decided against Peterson and ordered him to pay a $350 fine and nearly $100 in court costs, Peterson paid to get the vessel released immediately, and Swan filed an objection. He argued that the Bering Sea was an open sea and that no law of Congress could make it a mare clausum, or closed sea. He told the court that the ruling had made Peterson “suffer hardship and consequent loss” and that although the schooner owner would like to appeal the ruling, he lacked the financial means to do so. Swan wanted the district court to forward Peterson’s case as a claim for consideration by the court of arbitration in Paris, which would be adjudicating illegal seizures of Canadian schooners by US Revenue cutters. Agent Powell concurred, asking the Office of Indian Affairs to tell him how Makahs could file for their share of the $470,000 award issued by the Paris court.69 The department ignored this request, however, because the award applied only to British vessels seized by US Revenue cutters. During the tribunal’s hearings in Paris, arbitrators made it clear that they would not consider claims of British-licensed vessels owned by US citizens. Closing a potential loophole in the settlement, the tribunal would determine claims to be valid only if British citizens owned these vessels.70

At the same time, Makahs of the late nineteenth century encountered local courts and judicial officials increasingly hostile to Native sealers and indigenous vessel owners. In November 1893, Koatslanhoo (Makah) leased the Mary Parker to Captain Frank Bangs of Seattle for coastal trading. Bangs insured the schooner and cargo in his name, scuttled it in December, and pocketed the insurance money. When Koatslanhoo sued, the federal court acquitted Bangs because he employed “able counsel” and Koatslanhoo recovered nothing, despite the jury’s acknowledgment that the captain had scuttled the ship.71 In 1895, Judge Hanford—the same official who had decided against Chestoqua Peterson several years earlier in the case of the James G. Swan—refused to hear the case of a white sealer, Henry Anderson, accused of murdering Philip Brown (Makah) as the two divided their catch of seals at Ozette. Although a Port Angeles judge ordered Anderson to appear before the US district court and set bail at $5,000, Hanford referred the case back to the local court, whose jury released the white murderer.72 With growing numbers of Euro-Americans in the new state, officials and colonial juries were more interested in privileging whites over Indians.

But even in this settler-colonial regime growing increasingly hostile to American Indians, not everything hampered the ability of the People of the Cape to continue succeeding in the sealing industry. In 1894, the US and British governments agreed to follow a modified version of the recommendations of the tribunal of arbitration in Paris. Unknowingly echoing James Swan’s argument from two years earlier, the Paris tribunal decided against the US claims that the Bering Sea was a mare clausum and that seals swimming in the North Pacific were exclusive government property. Instead, the tribunal made several recommendations to conserve the Pribilof herd. They proposed a closed season from May 1 to July 31 in the North Pacific and Bering Sea and prohibited firearms and other explosive devices in the hunting of seals. These conservation measures provided both confusion and opportunity for Makah sealers and schooner owners.73

The closed season caused some trouble for indigenous sealers. Although required to notify schooners of the beginning of the closed season, US Revenue cutters passed the Makah fleet anchored at Neah Bay for weeks without telling them of the upcoming date. Instead, in June the Revenue cutter Grant seized two Makah schooners, the Puritan and the C. C. Perkins, weeks after they had reportedly sealed during the closed season. Citing the fact that the cutters ignored Euro-American vessels in Puget Sound ports, even though everyone knew that they, too, had sealed illegally in the Bering Sea, Agent Powell begged Captain Dorr Tozier of the Grant to release the schooners. It appeared that the cutters had unfairly targeted Makah schooners once again. The cutters released the vessels only after Swan petitioned the secretary of the Treasury on behalf of the Makah owners. Makah sealers lobbied federal officials for a partial exemption to the closed season because it prohibited sealing during May, one of the best months for marine conditions off the Washington coast. Although their agent and the acting secretary of the Interior supported this request, the government failed to grant an exemption.74

The Paris tribunal’s 1894 prohibition on firearms, however, worked in favor of indigenous sealers because they alone were proficient in the use of spears. After learning about the 1894 regulations, a local newspaper noted jealously, “Ten schooners for sealing voyages are being fitted out by the Makat Indians of Neah Bay. The fleet will be worth over $20,000, and will be entirely owned, officered and manned by aborigines. As the regulations as laid down in the Paris tribunal forbid the use of firearms in sealing, the Indians will have a decided advantage in the industry, since at handling the spear they are experts.”75 Anticipating an attitude that would resurface in many US treaty rights debates in the twentieth century, this white Canadian commentator objected to the “special rights” the regulations appeared to confer on Indians. This situation must have been especially galling to non-Natives already suffering from the global depression of the 1890s.

Under the new conservation regulations, Makah sealers did very well. During the first year of the firearms prohibition, the People of the Cape caught more than 2,500 seals off the coast of Washington. In 1895, Jongie took the Deeahks to the Bering Sea and brought back nearly six hundred skins after two months of hunting. According to the agent at Neah Bay, this was one of the best years for Makah sealers, who earned over $44,000 ($1.2 million today) during several months of work. The following year, the Claplanhoos hired Henry Hudson, an experienced Quileute captain, as master to take the schooner into the Bering Sea, which netted them over five hundred skins.76 These returns compared well to those taken from the Bering Sea in the years before the Paris tribunal’s regulations. This success demonstrated to the federal government and the North America Commercial Company, the new lessee of the Pribilof Islands, that the firearms prohibition was no disadvantage to experienced indigenous pelagic sealers. Further steps were necessary for conserving the herd from Indian hunters.

The late 1890s were a critical turning point for Makah sealers because national laws privileged powerful and well-connected business interests over small, family-run operations such as the Claplanhoo fleet. Darius Ogden Mills, the principal NAAC shareholder, had strong ties to the Republican Party. His political connections with President Benjamin Harrison likely helped to secure the twenty-year lease in 1890, and they probably served the company well when the Republicans took back the White House and won strong majorities in Congress in the 1896 election. Big businesses such as the North American Commercial Company supported William McKinley and contributed to his victory, so it should come as no surprise that in the first year of his presidency, McKinley backed and signed a congressional act protecting the monopolistic company at the expense of small sealing operations. This measure prohibited all US subjects from pelagic sealing in the North Pacific and Bering Sea.77 From the perspective of the federal government and the North American Commercial Company, this legislation was necessary because the pelagic catch from 1890 to 1896 was nearly three times higher than the land catch, and pelagic hunters killed more than they caught. Coastal Natives such as the Makahs would be exempt from the prohibition, as long as they hunted seals for subsistence purposes and from canoes with spears. They would not be able to use schooners to support their hunting efforts, nor could they engage in any form of commercial sealing, the cornerstone of the economy of the People of the Cape at this time.