MUSIC

Behind the scenes, music is more often than not the storyteller’s fuel. Consider Stephen King’s affection for heavy metal—and the way he’s woven some of his favorite lyrics and images into his classic works.

On the other hand, musicians have equally been inspired by SFF storytelling of a more textual—or visual—nature, and often sought to tell science fiction stories of their own. This chapter explores landmark concept albums that from the 1960s onward, turned music into a bona fide genre of SFF storytelling . . . as well as some of the ambitious (maybe too ambitious) science fiction and fantasy albums that never made it to shelves.

Science-Fiction Storytelling in the 1960s and ’70s, Set to Music

Just as the 1960s welcomed a New Wave in science fiction literature (see this page), it also marked the beginning of an SFF musical renaissance that lasted well into the 1970s. Pop culture was alight with the excitement of the Space Age. The generation’s brilliant minds were reading Tolkien and T. H. White, Asimov and Heinlein, and the iconography of both ancient epics and futuristic galaxies filtered into their own creative efforts. The free-flowing LSD inspired plenty of weird and trippy work as well.

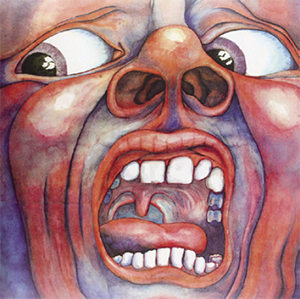

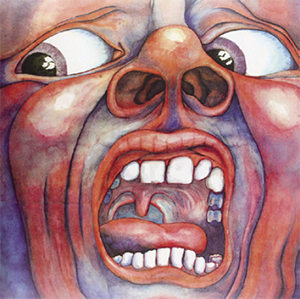

Writing for the Guardian on the 2009 release of a 40th anniversary re-mastered version (with surround sound mixed by Steven Wilson), Graham Fuller called In the Court of the Crimson King “the masterpiece that essentially launched progressive rock.” The band, and the album, have inspired other groups discussed in these pages, such as the Mars Volta. In 2019, the hyper-influential album will celebrate its 50th anniversary.

One of the era’s most ambitious concept albums was In The Court of the Crimson King (1969), the debut album from British prog-rock band King Crimson. This highly influential album is an anti-war polemic that cloaked its criticisms in the allegory of good and evil, blending soaring drama and psychedelic sound. It also inspired Stephen King, who took the name “the Crimson King” for his epic fantasy series The Dark Tower.

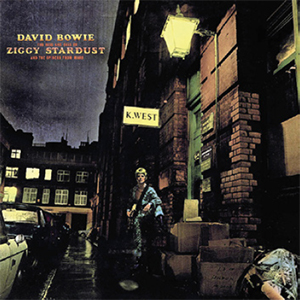

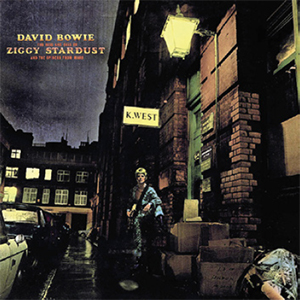

In 1972, David Bowie delivered what is possibly the greatest SF concept album of all time: The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. This ambitious glam-rock opera tells the story of Ziggy Stardust, a supernatural bisexual rockstar with a magnetic charisma and an alien connection. Ziggy Stardust is the messiah sent by aliens to deliver the human race from selfishness, violence, and greed. Bowie was a fan of William Burroughs and Stanley Kubrick, both inventive and experimental science fiction storytellers in their own medium, and was inspired by their work. In his book Strange Stars, Jason Heller describes how Burroughs’s use of collage and deconstruction techniques inspired Bowie’s work: “A pioneer of post-modern sci-fi pastiche as well as the literary cut-up technique, in which snippets of text were randomly rearranged to form a new syntax, Burroughs straddled both pulp sci-fi and the avant-garde, exactly the same liminal space Bowie now occupied.”

David Bowie’s tragic passing from cancer in January 2016 prompted a global outpouring of mourning and commemoration, leading many to revisit the artist’s greatest works from over the decades. Many of his albums re-entered the Billboard 200 chart, including The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars, which peaked at No. 21, forty-four years after its initial release. Blackstar, his final album, released just two days before his death, debuted at No. 1.

Burroughs and Bowie met for a discussion published in Rolling Stone—a sort of mutual interview between two great minds. During this conversation, Bowie sketched out his own interpretation of Ziggy Stardust: “The time is five years to go before the end of the Earth. It has been announced that the world will end because of a lack of natural resources. Ziggy is in a position where all the kids have access to things that they thought they wanted. The older people have all lost touch with reality, and the kids are left on their own to plunder anything. Ziggy was in a rock ’n’ roll band, and the kids no longer wanted to play rock ’n’ roll. There’s no electricity to play it.”

It’s an incredibly influential album, no less because as he took on the persona of Ziggy Stardust, David Bowie inspired a generation of queer and questioning kids who fell in love with his unapologetically androgynous, flamboyant, bisexual persona. He didn’t just invent Ziggy through music—he lived him through fashion and style.

Soon after came Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon (1973), the height of prog rock, a hippie classic, and one of the bestselling albums of all time. It explores the cosmic concerns of space, time, and the human experience. If you were born in the seventies or eighties (or, let’s face it, the nineties), there’s a good chance this is the album your dad jammed to while getting high in the garage. It’s not Pink Floyd’s only sci-fi influenced work by any means—some of their other great songs include “Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun” and “Interstellar Overdrive.”

In 1975, the universe welcomed Parliament’s Mothership Connection. Beyond the long shadow it cast on the funk music genre, Mothership Connection marked a major milestone in science fiction storytelling by bringing Afrofuturism to a popular audience (as Nisi Shawl explores on this page). This mythology laid groundwork for new threads of Afrofuturist storytelling across genres—not just the music of twenty-first century innovators like Deltron 3030 and Janelle Monáe (see this page and this page), but also some of the best speculative work emerging today in fiction, film, and comics.

With lyrics like “light years in time, ahead of our time, free your mind and come fly with me,” Mothership Connection invited its listeners to embark on a journey toward a different future. It presented a mythology in which funk music is the key to building a better world, casting Black people as the heroes and heroines of an epic science fiction story.

In 1976, Rush released one of the final big concept albums of the era: 2112. The story is told via the twenty-minute title track, which occupied one entire side of the band’s breakthrough album. The grandiose sci-fi storytelling is underlined by deep cuts and conveyed via a high-charged wall of sound that’s both dynamic and volatile, frequently changing pace to match the emotional highs and lows of the narrative.

Naturally, the story takes place in the year 2112, when the world is ruled by the oppressive Solar Federation. Art and music are regulated by priests—until a guy finds an old-ass guitar and discovers the pleasures of the forbidden. The priests of the Temples of Syrinx can’t let that stand; they destroy it. This young martyr to the music kills himself in protest, provoking chaos . . . and the beginning of a new era. Consequence of Sound calls the story a “classic tale of the individual versus an oppressive, collectivist entity,” comparing the world of 2112 to “Winston Smith’s world in 1984 or that of John the Savage in Brave New World.”

2112 is right up there with Ziggy Stardust and the Crimson King for greatest concept album in the universe. In future albums, Rush continued to explore science fiction themes, depicting an interstellar voyage through a black hole in the lengthy tracks “Cygnus X-1” and “Cygnus X-1 Book II,” respectively found on A Farewell to Kings (1977) and Hemispheres (1978).

Just as the musicians who created these works were inspired by their favorite SF novels—often the tales they’d treasured as children—the vast mythologies hinted at in these albums went on to inspire a new generation of writers, who found in fragments of lyrics, and the feelings they evoked, the genesis of their own speculative stories. And the interchange and interplay between musicians and writers continues. *

NISI SHAWL

Astro Black

The future looked black. More to the point, it sounded black. Back in the mid-1970s, pre–President Reagan, post-MLK, Parliament/Funkadelic gave up the intergalactic funk in honor of an awakened community of musically oriented science fiction fans. Or perhaps it’s more accurate to describe them as SF-oriented music fans? At any rate, their semi-cargo-cultish audience eagerly absorbed the group’s outlandish, nay, offearthish stylings. The 1976 Mothership Connection tour featured a smoke-shrouded pyramidal spaceship cajoled into landing onstage by a song; the show’s star Afronauts wore silver lamé platform boots and swooping capes and collars, while the rest of the crew sported dangling furs, bobbing feathers, and bug eyes. Lyrics exhorting listeners to bathe in the healing energies broadcast by their radios and promising to expand their molecules, personae with names like Starchild and Dr. Funkenstein—all these deliberately chosen images and elements and a myriad more underscored P-Funk’s science-fictional bent. Those predilections had their predecessors.

One of the most frequently cited of Parliament/Funkadelic’s predecessors is Sun Ra (1914–1993), the highly theatrical jazz composer and perfomer, who many claim was Afrofuturism’s Ur-musician. Long, long ago—In the thirties? Forties? Fifties? Accounts vary.—following a non-corporeal journey to a planet he believed was Saturn, Sun Ra began spreading the news that space was the place. From the fifties through the early nineties he played avant-garde jazz alongside an ever-changing lineup that at times included thirty musicians, singers, dancers, and fire-eaters. “It’s after the end of the world, don’t you know that yet?” he asked on the 1970 live album It’s After the End of the World, making it clear that his forays into the speculative encompassed not just space but time.

Another influence, and a near contemporary: Jimi Hendrix (1942–1970). Guitarist Eddie Hazel was an obvious Hendrixite, and the psychedelic component of P-Funk’s shows and recordings has often been linked to Hendrix. But what about that SF content I mentioned? Plenty of Hendrix songs—“Third Stone from the Sun” and “1983 . . . (A Merman I Should Turn to Be)” to name a couple—are solidly genre. His love of Flash Gordon movies and postapocalyptic novels is documented in books and articles. Did Messrs. Clinton and Hazel (as well as P-Funk mainstays Bernie Worrell and Bootsy Collins) neglect that aspect of Hendrix’s pioneering work when taking inspiration from it? Doubtful.

Why, though, does Afrofuturism resonate so strongly in the echoing halls of musical knowledge? Perhaps, partly, for the same reason it’s a force to be reckoned with on any curve of the Afrodiasporic sphere: alienation and cognitive dissonance, the mainstays of the SF experience, science fiction’s hardcore jollies, are, for us, the default. As a child I tried to explain this to a white neighbor by sharing my theory that I came from Mars. Outsiders make myths of our exclusion. And then we play those myths, and sing them, and dance them, because we recognize that artistic expression of a truth makes it even more valid. Science fiction, as author Greg Bear says, is the modern mythos.

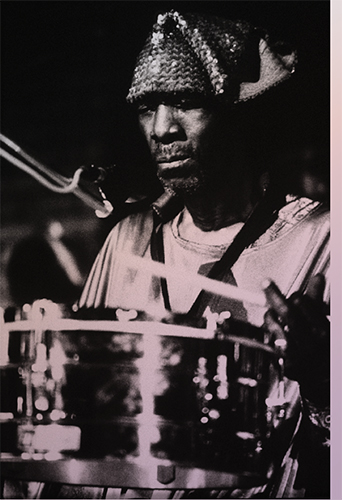

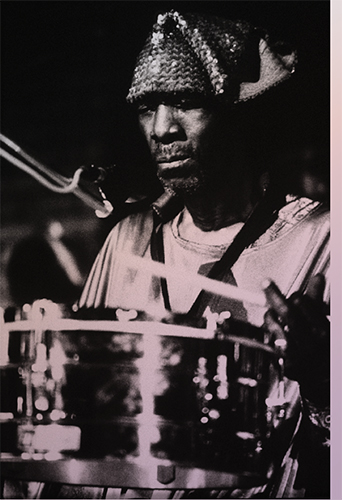

Saxophonist John Gilmore, a member of Sun Ra’s Arkestra, in 1990. The Arkestra was a flexible, ever-evolving ensemble of dozens of musicians that Ra led for decades. The Arkestra often performed in fantastic costumes that blended influences from Egyptian myth and iconography and Space Age science fiction, creating an early aesthetic for Afrofuturism. Photo credit: Sefton Samuels / Shutterstock.

So the intersection of music and Afrofuturism is a regularly visited spot. Sun Ra, Jimi Hendrix, Parliament/Funkadelic to be sure—and P-Funk’s contemporaries, too: Sly & the Family Stone, who accompanied the band on the Mothership Connection tour; Gil Scott-Heron, who predicted worldwide transformation in “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”; Earth, Wind & Fire, whose neo-Egyptian symbolism and proselytizing for Cosmic Consciousness fit right in with the Afrofuturist tradition.

It’s a living tradition. It can be found anywhere you look. Punk rock embodied Afrofuturism, if only briefly, in Poly Styrene, lead singer of X-Ray Spex. (Her songs “Germ Free Adolescents” and “The Day the World Turned Day-Glo” come particularly to mind.) Disco and New Wave diva Grace Jones has always been presented as beautifully inhuman, erotically robotic, and shockingly unearthly through her hair, clothes, makeup, and mannerisms. Yet another quondam disco star, Michael Jackson, was known for “moonwalking,” a dance move that seems to defy mundane causality. Jackson performed several Afrofuturistic numbers in the years following that early part of his solo career. His hit dance tune “Another Part of Me” first appeared in 1987 in the indubitably science-fictional short film Captain EO. “Remember the Time,” released in 1992, foregrounds the familiar Afrofuturist Egyptian aesthetic; “Scream,” released in 1995, originally accompanied a video in which MJ and his sister Janet sang and danced aboard an orbiting spacecraft.

Throughout the eighties and nineties, electronica and house—originally black musical forms—helped Afrofuturism keep on keepin’ on. Some SF authors had begun by then to lament the growing difficulty of writing about a future that got closer and closer every day. They complained that fast-paced innovation overtook their storylines, but electronica started off inviting listeners to discover the future by living in it, and went on to celebrate what could be found there.

Something experiential and empirical in the nature of music blends nicely with African-based attitudes toward science, time, and technology. This may be why the flow goes both ways, into the aural realm and out of it. Not only does genre fiction inspire Afrofuturist music, the music’s figures and numbers and other components inspire genre fiction—as when, for example, an avatar of P-Funk’s Starchild appears in my 2008 story “Good Boy.” Or when an anthology collecting that story is titled Mothership. Or sometimes when an Afrofuturist composer and performer such as DJ Gabriel Teodros writes the stuff himself. His 2015 story “Lalibela” appears in Octavia’s Brood: Science Fiction from Social Justice Movements and is reprinted in Volume 1 of the Sunspot Jungle anthology.

Because of this ongoing back-and-forth, and with Beyoncé (“Single Ladies”), Kendrick Lamar (“Alright”), and Janelle Monáe (The ArchAndroid) constantly updating Afrofuturism’s sound, scholars like Kinitra Jallow, Erik Steinskog, and DJ Lynnée Denise have endless sources of new material to examine in their studies of the subject. And those of us less studious have endless sources of material to which we can shake our multidimensional booties. *

The Who’s Lifelong Search for the “One Note”

After the massive critical and commercial success of Tommy (1969), a rock opera about an abused boy, the Who found themselves in search of an equally ambitious concept for their next album. For lead guitarist and songwriter Pete Townshend, that concept was Lifehouse—a science-fiction rock opera that would expand the potential of audience participation to dizzying new heights. The album would be supplemented with film and live performances, making it a full multimedia experience.

The Lifehouse storyline went through several iterations, but here’s the general thrust of it: In the not-too-distant future, environmental degradation means most people are locked up inside their houses 24/7, where they encounter the world solely through their connection to an experience/entertainment network called “The Grid.” (If you’re thinking that sounds a little like the Internet, you’re not alone.) Basically, the populace spends their lifetimes jacked into virtual reality, wearing haptic feedback suits to enhance the experience.

Of course, in 1970 there wasn’t much popular terminology for virtual reality or haptic feedback suits; no one had even seen The Matrix. Perhaps this was Lifehouse’s downfall; as Pete Townshend tried to explain his brain-busting concept to his bandmates and manager, they were just like “. . . We don’t get it.”

Anyway, in this world governed by virtual reality, a hacker named Bobby discovers rock ’n’ roll, which is outlawed by the Grid. Bobby lives outside the virtual reality network—you could say he’s taken the red pill—and so from his position in a commune of fringe-people and farmers, he begins broadcasting classic rock to the helpless denizens of the Grid. The music will happen live in a concert hall called Lifehouse, played by none other than the Who. Like Mothership and Rush, this story would lean into its own medium by casting music as a powerful and mystical force and the key to freedom from oppression.

The Lifehouse narrative focuses on a family of humble turnip farmers, who also live outside the Grid, in the unpolluted wilderness of Scotland. Their teen daughter Mary runs away to go to the concert. This is where narratives diverge; in some iterations, the parents go after her together, in others it’s just Ray. Anyway, Ray and sometimes Sally arrive at the rock festival just in time to find Bobby and the band hitting the One Note . . . that one powerful and mystical sound, fully in tune with the vibrations of the universe, that unites all people and achieves world peace.

The Who performing in Chicago in 1975. Left to right: Roger Daltrey, John Entwistle, Keith Moon, Pete Townshend. Photo credit: Jim Summaria.

Perhaps even more complicated than the virtual reality stuff was Townshend’s conception of music as a metaphysical force. The idea was that Bobby, on his path to the One Note, would create songs that uniquely represented individual audience members, connecting directly to their souls. More challengingly, Townshend imagined that in their role as the band, the Who would find a way to do the same thing. It’s one thing to envision the supernatural; it’s quite another thing to aspire to execute it. In 1978, Townshend admitted as much to Trouser Press: “What fell apart with it . . . was that I actually tried to make this fiction that I’d written happen in reality. That’s where I went wrong, actually trying to make a perfect concept.”

Their attempts to capture the sublime began and ended at the Young Vic, a theater in London where the band booked a months-long residency. The goal was to develop the concept through daily live performances in which the band’s synergy with the audience would organically melt into total harmony. Instead, the confused audience heckled the new material and demanded to hear the hits.

Under pressure from the rest of the band, Townshend reluctantly gave up the Lifehouse concept. They narrowed the material down to the strongest songs, which became the basis for a non-concept album, Who’s Next—widely regarded as one of the best rock albums of the twentieth century. Those songs include “Baba O’Riley,” “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” and “Behind Blue Eyes,” some of the Who’s biggest and most enduring hits.

But Pete Townshend remained fascinated by the SFF elements of Lifehouse and never abandoned his vision for it. He drew on it heavily for inspiration on his 1993 solo album Psychoderelict. In 1999, the BBC produced Lifehouse as a radio play. In 2000, Townshend released a six-disc boxed set called Lifehouse Chronicles.

Lifehouse Chronicles includes original 1971 demos of Lifehouse songs, live recordings, new studio recordings, orchestral arrangements for the radio play, and the radio play itself. Unfortunately for Lifehouse fanatics, the full box set is out of print and hard to find; used copies go for $300 or more online. On the other hand, Lifehouse Elements—a one-disc sampler with eleven tracks—is widely available, and offers a rousing glimpse of the Lifehouse that could have been. *

JOHN CHU

Sweet Bye and Bye and Speculative Fiction in Musical Theatre

Scientists have located, “under the waters of Flushing Bay,” the time capsule buried during the 1939 New York World’s Fair. On the United States’ tricentennial, scientists recover and open the capsule. They find among its contents a letter from a Solomon Bundy to his namesake in the future. He bequeaths his future namesake five shares of stock in the Futurosy Candy Corporation, which is now “the biggest candy cartel there is.” These five shares from 137 years ago gives his namesake a controlling interest in the company and make him one of the wealthiest people in the world.

The Solomon Bundy of 2076 is a tree surgeon who thinks of himself as being “born too late.” He is completely unprepared to be the president of the Futurosy Candy Corporation. This is, of course, precisely what he has just become.

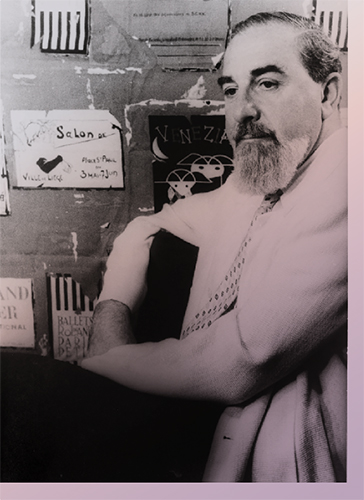

This reads like the setup for a science fiction satire. And it is. But it’s also the 1946 musical Sweet Bye and Bye, featuring robots and a partially drowned New York City, not to mention a second act where Solomon Bundy flees to Mars on a space liner. The pedigree of the creative team was also out of this world, with a book by S. J. Perelman, the revered New Yorker writer and humorist, and Al Hirschfeld, the legendary caricaturist, lyrics by Ogden Nash, the popular poet, and music by Vernon Duke, whose collaborators over his career included Ira Gershwin and Johnny Mercer. Sadly, despite all this talent, the original production failed before it reached Broadway. The score was thought lost for decades until it was rediscovered in a warehouse in Secaucus, N.J., in the mid-eighties, but happily, sixty-five years after the show opened, it was made into an audio recording in 2011.

Setting Sweet Bye and Bye in the future heightens what Tommy Krasker, the producer of the 2011 recording, identifies as the theme of the show: “How do you really find your way in a world of limitless possibilities?” Unfortunately, while this was the show Duke and Nash wrote, what Perelman and Hirschfeld wrote was a farcical revue. The show then had an exceptionally difficult out-of-town tryout. The original leading man couldn’t sing. His replacement couldn’t remember lines. The original leading lady had a nervous breakdown (but was replaced by Dolores Gray). The show closed in Philadelphia, canceling its Broadway run. As brilliant as the score was, the book didn’t work, and fixing it left the score in tatters. There was never a version of the show to present both elements in their full genius. (Although one can listen to the 2011 recording and imagine the wonderful show that could have been.)

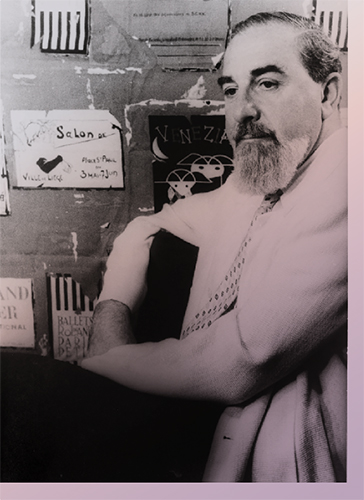

Caricaturist Al Hirschfeld, who contributed to the book for Sweet Bye and Bye. Photo credit: Carl Van Vechten.

Despite the heavy hitter talent behind Sweet Bye and Bye, it is not a successful example of the subgenre, but there are a surprising number of shows that do work.

Theater, from its various origins, has always included the fantastic. So works like Kurt Weill’s One Touch of Venus (1943), where a statue becomes the literal goddess Venus, have never been out of bounds. Even in works that are essentially mimetic, like Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel (1945) and Damn Yankees (1955), Billy Bigelow tries to fight his way into heaven in the former, and Joe Boyd makes a pact with the Devil, kicking off the plot of the latter.

Musicals like Kurt Weill and Alan Jay Lerner’s Love Life (1948), Leonard Bernstein’s 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue (1976), and Heading East (2001) play with time differently than Sweet Bye and Bye. They span multiple centuries while their characters age only years, if at all. This drives home that the struggles in marriage, American democracy, and Asian American immigration recur over the broad sweep of history. Speculative devices function for works meant to be performed in the same way they function for works meant to be read—they heighten those works in a way that would be more difficult, if not impossible, without them. *

ANNALEE NEWITZ

X-Ray Spex, Poly Styrene, and Punk Rock Science Fiction

In the mid-1970s, a young woman from Brixton named Marianne Elliott-Said had a profoundly transformative experience. She went to a Sex Pistols concert and was galvanized by the realization that punk meant expressing herself however she wanted. Shortly thereafter, she saw a fiery pink UFO hovering in the skies over Doncaster. By 1976, she’d taken the name Poly Styrene and formed a punk band called X-Ray Spex, whose singles “Oh Bondage Up Yours,” “Identity,” and “World Turned Day-Glo” rocketed up the charts. Though X-Ray Spex only released one album, Germfree Adolescents (1978), the band had a profound effect on punk rock, feminist fashion, and science fiction.

Proudly calling herself “artificial” and “a poseur,” Poly sang about a future of genetically-engineered humans, consumer droids, environmental apocalypse, and mind-blowing explorations of outer space. Wearing retro fashion mixed with gilded junk, she belted out songs that combined elements of ska, punk rock, and new wave synth weirdness. In 1977, she told an Australian TV interviewer that her trippy sound and look weren’t about LSD, but futuristic fantasy: “I wanted to write something using all kinds of plastic words and artificial things and sort of make a fantasy around it. It’s about the modern world.”

Germfree Adolescents should be read in the tradition of Samuel Delany, Octavia Butler, and Joanna Russ, with some sarcastic notes of Philip K. Dick thrown in for good measure. In the song “Genetic Engineering,” she gives us a future ruled by biologists, where a “worker clone” is a “subordinated slave” ruled by “expertise proficiency.” But in the song “Plastic Bag,” she’s become a clone herself, calling her mind a “plastic bag that corresponds to all those ads.”

Poly’s lyrics were often absurdist and surreal, almost as if she were channeling Delany’s Dhalgren. But there was also no mistaking her rage. Like Russ and Butler, whose characters are often treated like aliens and monsters by the men around them, Poly wanted the world to know what it felt like to be a mixed-race woman in a scene dominated by white men.

Her song “Identity” tackles this head-on, asking, “Do you see yourself on the TV screen . . . When you see yourself does it make you scream?” Here she’s grappling with the problem of representation in the media. Like many punk and ska acts inspired by her, from the Specials to Bikini Kill, Poly loved to dress up in outfits that were arresting precisely because they defied gender norms. In the song “Highly Inflammable,” she trills about a person who is both man and woman, who “wants to join the hermaphrodite clan.”

X-Ray Spex in concert, September 14, 1991. Photo credit: Ian Dickson / Shutterstock.

Over a decade later, intersectional and queer feminists would explore this issue, highlighting how women of color in mass media are either demonized or rendered invisible. In her lyrics, Poly calls identity a “crisis you can’t see.”

Early in her career, Poly explained that her obsession with artificiality came from women’s punk fashion, recalling that she started writing “Oh Bondage Up Yours” after a Sex Pistols show where she saw “two girls handcuffed together.” Poly liked the way they were “drawing attention to the fact that they were in bondage as opposed to pretending they weren’t.” For Poly, bondage wasn’t just a matter of identity. It was about a future ruled by consumerism. “Oh Bondage Up Yours” describes a fake consumerist utopia with wordplay: “Chain-store, chain-smoke . . . chain-gang, chain-mail!” She throws off her bondage by immersing herself in it completely. “I consume you all!” she screams in the chorus.

The science fiction of X-Ray Spex was ahead of its time. Poly was an intersectional feminist in an era when that concept had no name. And she was describing a cyberpunk future long before cyberpunk became popular. Her music gave voice to a generation for whom authenticity was artificiality, and futurism felt like a dead end.

Though she struggled with depression that often kept her out of the limelight, Poly continued writing genre-inspired songs until the end of her life. Her final album, Generation Indigo, was released in 2011 a month before she died at fifty-four of metastatic breast cancer. Like all of her work, it was eclectic; there’s an electroclash satire of MySpace culture called “Virtual Boyfriend,” and a dreamy post-punk song called “Ghoulish” about loving creatures who seem monstrous but are actually just nice guys.

In the video for “Ghoulish,” we’re given a final glimpse of the alternate future world that Poly made real for so many young people who never saw themselves on TV. We watch a surreal version of American Idol unfolding, as mixed-race kids and queers dance for judges who offer bizarro commentary. Finally, a Michael Jackson impersonator lights up the stage with amazing moves and magical glitter powers, the judges cheer, and we have our new idol. The room fills with dancers, many of them mixed-race and androgynous, and we zoom in on the winner. He looks up from beneath his white fedora . . . and we realize this Michael Jackson clone has been female all along. She turns to the camera, her face alight with mirth, and lip syncs to Poly Styrene singing, “I’m not so foolish to be scared.”

This moment sums up what Poly Styrene has left in her wake. It’s a narrative fusion of sharp social satire and playfulness that keeps the world’s horrors at bay. But it’s also a promise. Maybe one day, in a world without slave clones, we’ll see ourselves on the mobile screens and it won’t make us want to scream. *

Weezer’s Songs from the Black Hole

Weezer’s first album, Weezer (aka The Blue Album), went triple platinum when it was released in 1994, and launched the band to sudden and stratospheric success. Lead singer Rivers Cuomo felt that he, too, had been launched into outer space . . . and for the band’s sophomore effort, they set out to make a concept album exploring the experience. As Ryan Bassil put it in Noisey, “Blue Album had been released to critical acclaim and Rivers Cuomo, a maverick in despondency, had mixed feelings about its success.”

Weezer released their eleventh album in October of 2017. The band’s creative inspiration for Pacific Daydream is “reveries from a beach at the end of the world,” and includes the hit “Feels Like Summer.”

The album would have been a musical space opera, titled Songs from the Black Hole. Cuomo envisioned Songs from the Black Hole in the tradition of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, as one coherent, flowing musical narrative. The band wrote the songs and shared two track lists, but the album’s concept was eventually rejected, and Songs from the Black Hole was never officially released. Many of its songs were eventually recorded and released in other forms. With the track lists and lyrics floating around on the Internet, plus some eventual versions of the songs, it’s possible to piece together a vision of what might have been. But the full album in its bombastic and space-operatic glory was never truly realized, to the lasting disappointment of fans.

The album’s story is reminiscent of the best YA SF drama, a “space opera” that’s definitely heavier on the opera than it is on the space. A group of the top young graduates from the Star Corps academy are on a mission in space, which is to stop a planet called Nomis from getting “swallowed by its sun” . . . but their main focus seems to be on who’s boinking whom. (And yes, “boink” is a direct quote.) “Basically, the concept was bat-shit crazy ridiculous,” concludes Vice.

The lead character is Jonas, the moody, brooding ship’s captain, jaded and depressed by the whole space travel experience, and caught in a love triangle between two shipmates, Laurel and Maria, an allegorical representation of Cuomo’s own love troubles at the time. Meanwhile, Jonas’s buds Wuan and Dondo—stand-ins for his bandmates—are eager and enthusiastic about the trip to space. The ship, Betsy II, is named after Weezer’s tour bus, which they called Betsy.

Maria is a friend with benefits who wants something more, while Jonas keeps jerking her around. His friends talk shit about her. Dondo calls her a “cheap ho,” and Jonas sets out to comfort her, telling her he hates Dondo . . . who “acts like he knows he’s got a big dick.” (Keep this in mind; it will be important later.) The long middle of the narrative is mostly Jonas angsting about various things, like how annoying it is that all his fans constantly want to have sex with him, and how getting what you want is never as amazing as you think it will be.

They finally prepare to land, to the great excitement of Wuan and Dondo and the typical pessimism of Jonas, who demands to know why they even bothered to yank him out of his pod. (Earlier in the album, Maria begs him to come to her pod, and they discuss the types of leisure activities they could enjoy within its privacy. Perhaps the fact that Jonas is now alone in his signifies some trouble in paradise.)

Then . . . SPOILER ALERT! . . . Maria gives birth to Jonas’s kid, a baby girl. Awestruck and emotional to meet his offspring, Jonas is finally ready to commit. “She’s Had a Girl” is a sweet, haunting song that might even make an OK lullaby. Jonas’s backup girl Laurel dumps him, despite the fact that she still loves him; this song, “I Just Threw Out the Love of My Dreams” is one of the most compelling songs from the album, a catchy and affecting number sung by Rachel Haden.

But alas, Jonas should have put a ring on it, for his return to Maria reveals an unsettling discovery . . . a used condom. An extra-large used condom. Who could have left behind such an artifact? Well, none other than Dondo, his shipmate with the big dick.

The final song, titled “Longtime Sunshine,” sees Jonas singing wistfully of purer and simpler times. He elects to stay behind on Nomis, perhaps to be devoured by the sun, which would explain the title. With all the relationship drama going on, it’s not exactly clear what happened regarding the mission or the fate of the sun-doomed planet. “Longtime Sunshine” is a wistful and melancholy song that also pulses with energy and a catchy, driving beat.

As a work of science fiction, the story leaves a lot to be desired. But as music—as a raw, unfiltered taste of Weezer during their most inspired period—it’s exhilarating and satisfying. It would be fantastic to hear the thing in its entirety, produced with full theatrics (heavy on the synthesizers). Along with the standout songs already mentioned, there’s the opening number “Blast Off!,” which Jason Crock describes as “a fleeting rush of distortion-driven joy.” Writing for Noisey (Vice), Ryan Bassil proclaimed the album “better than almost everything they’ve released in the last fifteen years.”

But it was not to be. Cuomo recorded some demos for the album during Christmas of 1994, using synthesizers he’d found at a pawnshop in Connecticut. The band continued to work on the album throughout the early months of 1995, but personal issues began to get in the way. In March, Cuomo underwent difficult and extensive surgery on his leg, followed by painful physical therapy. At the end of 1995, he enrolled at Harvard to study music. He found his time there lonely and isolating. He continued to suffer from chronic pain.

These difficult experiences pushed Cuomo’s creative interests in a different direction. Songs from the Black Hole was always kind of a goofy, tongue-in-cheek concept, good-naturedly accepting of its own ridiculousness. The whimsical tone no longer worked for him. Instead, he went in a darker, more confessional direction. The result was Weezer’s actual second album, Pinkerton. Cuomo called it “an exploration of my ‘dark side’—all the parts of myself that I was either afraid or embarrassed to think about before.”

Pinkerton was not treated kindly by critics, who’d expected something better, based on the success of the Blue Album—or at least something different. Cuomo himself eventually joined in on panning it, calling it a “hideous record” and a “hugely painful mistake.” He regretted the intensely personal nature of the album, telling Entertainment Weekly in 2001 that the experience was like “getting really drunk at a party and spilling your guts in front of everyone and feeling incredibly great and cathartic about it, and then waking up the next morning and realizing what a complete fool you made of yourself.”

Those scars took some time to heal, but they did. Eventually, Cuomo made his peace with the album. A retrospective look reveals its unmistakable impact on the world of rock ’n’ roll. Still, it’s tempting to imagine what might have been, and what direction a completed Songs from the Black Hole might have taken the band.

A few of the songs from SFTBH’s track list made it onto Pinkerton: “Tired of Sex,” “Getchoo,” and “No Other One.” These songs were written before the Black Hole concept came to be, so it was easy to transition them. Indeed, they make more sense on a confessional album like Pinkerton than they did as the diary of an angst-ridden and oversexed astronaut.

Two more songs from Black Hole were later released as Pinkerton B sides: “I Just Threw Out the Love of My Dreams” and “Devotion.” Five more songs made it into Alone: The Home Recordings of Rivers Cuomo, a demo compilation. Three more tracks made it onto Alone II, and six onto Alone III. Alternate versions recorded at shows also circulate on the Internet and among fans. With all this material to choose from, playlists approximating the imagined album can be found easily. So cue one up . . . and imagine. *

Speculative Music of the New Millennium

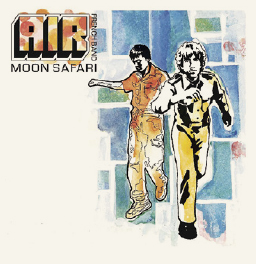

The dawn of the new millennium heralded a particularly rich moment for SFF-inspired music, and the late nineties and early oughts brought us several lasting masterpieces of the genre. Radiohead delivered the heavy hitters: OK Computer (1997) and Kid A (2000). The Flaming Lips contributed the unforgettable Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots (2002). And there were plenty of others: OutKast’s ATLiens (1996), Air’s Moon Safari (1998), Daft Punk’s Discovery (2001), Goldfrapp’s Black Cherry (2003), and The Mars Volta’s De-Loused in the Comatorium (2003).

Goldfrapp live at the annual Summer Series at Somerset House in 2017. Photo credit: Sonic PR/Daniel Roberts.

OK Computer regularly makes it onto lists of greatest albums of all time, so if you haven’t listened to it yet, you probably never will. Still, if you haven’t, you should. It’s a masterpiece that perfectly blends its many disparate influences into something altogether new. The album utterly encapsulates a mood that pervaded science-fiction storytelling in the late nineties: trepidation about the unknown future blended with a weary ennui at the isolation and inauthenticity of an artificial present. (Or as Newsweek puts it: “The terrifying and dehumanizing malaise of modern life and consumerist culture. Exhibit A: Every song on the album.”)

Also, one the album’s best-known songs is titled “Paranoid Android,” inspired by Marvin the depressed robot in Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Marvin also suffers from the galaxy’s most severe case of ennui, spouting grim lines such as “Here I am, brain the size of a planet, and they tell me to take you up to the bridge. Call that job satisfaction? Cos I don’t.” Meanwhile, on the track “Subterranean Homesick Alien,” “aliens hover making home movies for the folks back home,” and like the overlooked women in James Tiptree Jr.’s classic story “The Women Men Don’t See,” the song’s narrator only wants the aliens to take him with them.

While not exactly a concept album per se, Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots delivers a coherent narrative across several songs, more in the tradition of prog rock’s grand epics. Obviously, the heroine of this story is Yoshimi, a black belt and all-around badass, who along with an army of similarly badass girl warriors, is called to keep “the city” safe from the scourge of psychedelic robots with an evil plan for world domination. Her counterpoint is unit 3000-21, the robot who discovers in itself the seeds of humanity, “feeling a synthetic kind of love . . . one more robot learns to be something more than a machine.” Rolling Stone calls the Flaming Lips’ tenth album “a delightful iridescent bomb of buoyant electronics, imaginary Japanese anime and plaintive vocal surrender.”

After Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik put OutKast on the map as a majorly talented rap duo to watch, ATLiens solidified that reputation with its delightfully funky and futuristic hip-hop. The influence of George Clinton and the Parliament/Funkadelic collective is evident. ATLiens speaks to the duo’s feelings of alienation, and weaves a narrative of personal marginalization together with imagery from science fiction and folklore that expands the story into something much larger. The lyrics are both smart and catchy, and are underlined with addictive beats and spaced out sci-fi sound effects.

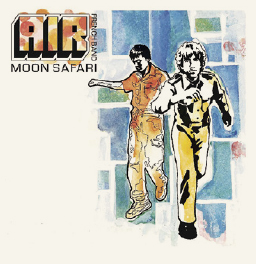

Air’s Moon Safari, Daft Punk’s Discovery, and Goldfrapp’s Black Cherry each offer a unique take on synth-pop electronica, with abstract, minimal lyrics and lengthy instrumental interludes. The science-fiction appeal of these albums is primarily in their enchanting space-pop sound. Moon Safari, for instance, includes the track “Kelly Watch the Stars,” whose lyrics consist of the one line “Kelly watch the stars” . . . repeated seventeen times. Slant Magazine writes of the album, “At the same time that it’s space-y and breathless, it’s also organic and downbeat; at the same time that it’s nostalgic, it’s also clearly planted in the future.” This is the music that plays in the passenger lobby of the space yacht while you wait for the hyperdrive to kick in.

The iconic cover art for Air’s debut album, Moon Safari, first released in 1998, with a tenth anniversary re-release from Virgin Records. Rolling Stone included it in a list of the best albums of the 1990s.

Like Air, Daft Punk is a French electronica duo. Discovery is a more uptempo album, with a pulsing dance beat and lyrics that are almost hypnotically repetitive. (This album includes the world-conquering workout anthem “Harder Better Faster Stronger.”) Treble Zine calls it “a record that truly sounds like an outer-space version of an ’80s rock band.” Discovery is primarily instrumental and doesn’t listen like a concept album, but in a fairly unprecedented move, the duo turned it into one—by releasing an animated movie alongside it that wasn’t widely seen.

Interstella 5555: The 5tory of the 5ecret 5tar 5ystem is a Japanese-French anime that tells a story solely through its visuals, using the entirety of Discovery as its soundtrack. Interstella 5555 is about a blue-skinned alien techno band kidnapped by evil earthling music executives (and followed by space pilot Shep, who is in love with bass player Stella). The band’s memories are reprogrammed and they are forced to perform as the Crescendolls (see Discovery, track five). Shep intervenes, and slowly the band overcomes their amnesia to piece together what happened and how they ended up here, so they can go back home. It’s a pretty hallucinatory ride, but critics hailed the trippy film as a success, comparing its kaleidoscopic pleasures favorably to Disney’s Fantasia. The film was created in a collaboration between Daft Punk, Leiji Matsumoto, Cédric Hervet, and Toei Animation, and reportedly cost $4 million to make.

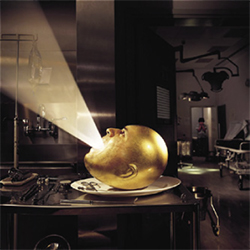

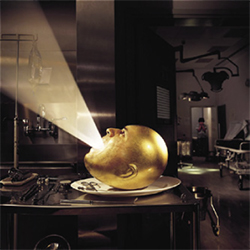

De-Loused in the Comatorium (2003), the debut studio album from the Mars Volta, with album cover art by Storm Thorgerson. This weird concept album follows the metaphysical journey of Cerpin Taxt. From the accompanying storybook: “Faith vanishings, hence the litter passing by muttering underbreath, and waterlike, I thought someone might still be able to spot me . . . testator nomadic. Trailing a tail of trick mirrors, hyperventilating as I did past my own temple.”

Goldfrapp’s Black Cherry is slinky, seductive, and charged with sexual tension. It’s the perfect album to accompany dark and erotic fairy tales for adults in the vein of Angela Carter, Tanith Lee, Helen Oyeyemi, or Catherynne M. Valente. Writing for Bustle on Alison Goldfrapp’s “fantasist’s dream” wardrobe, Freyia Lilian Porteous describes Goldfrapp’s music as “sparkling with something akin to both fairy dust and the sheen of a futuristic spaceship.” Perhaps not just a perfect accompaniment to Tanith Lee’s fairy tales, but her equally luscious and uniquely feminine science fiction stories, such as The Silver Metal Lover, Electric Forest, and Don’t Bite the Sun.

At The Drive-In live in concert in 1999 at 3B in Bellingham, Washington. Left: Omar Rodriguez-Lopez. Right: Cedric Bixler-Zavala on vocals. Photo credit: Jacob Covey.

The Mars Volta’s debut full-length studio album, De-Loused in the Comatorium, is about as far as you can get from Goldfrapp’s chilled out pop . . . but prog rock has its virtues too, as well as a storied legacy in the halls of SFF.

The Mars Volta formed in 2001 from the same duo who previously performed as successful band At The Drive-In: Omar Rodriguez-Lopez and Cedric Bixler-Zavala. This voluntary reinvention speaks to the innovative impulses that motivated the duo’s creativity—a desire to tread new territory. With De-Loused in the Comatorium they delivered that, and the album was both a critical and a commercial success. It pays tribute to their close friend Julio Venegas, an artist whose troubled life ended in suicide—after recovering from a drug overdose that left him in a lengthy coma. This tragic story is recreated in De-Loused as the fictional story of Cerpin Taxt, whose mind undertakes a series of nightmarish voyages as his body remains comatose following an overdose on morphine and rat poison.

Bixler-Zavala and Rodriguez-Lopez also wrote a storybook to be released alongside the album. This story weaves a more complex fictional narrative to accompany each song’s lyrics, detailing the people and places that Taxt encounters on his otherworldly journey. Much of this story, like the album’s lyrics, is a surreal and Burroughs-esque stream of consciousness whose chaotic litany of words evokes a vision through accretion rather than explanation. *

MARK OSHIRO

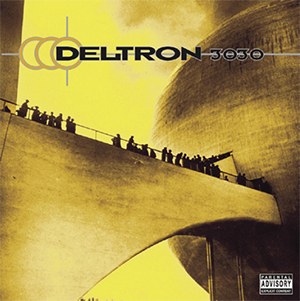

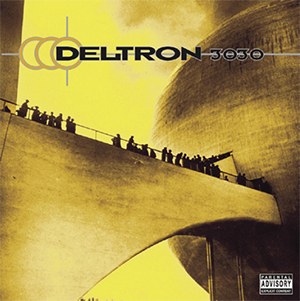

The Timeless Brilliance of Deltron 3030

It’s been nearly two decades since the world was given the debut record from Deltron 3030—the hip-hop supergroup comprised of Del the Funky Homosapien, Dan the Automator, and Kid Koala—and yet Deltron 3030 remains relevant, prescient, and exciting. It came out while I was in high school, right at a time where I was thirsting for more—for art that addressed the oppressive structures that dictated the difficulties in my life. For music that made me feel less alone. For the escapism of densely-constructed worlds. Del’s lyrical complexity and vocal uniqueness—which I’d fallen in love with on his fourth album, Both Sides of the Brain—was present here. He’s got a voice that is instantly recognizable, and even to this day, no one sounds like Del. But this voice was paired with a sweeping, operatic story set in the year 3030, where hip-hop is the last hope in a society ruined by a set of oppressive oligarchs.

I devoured it. Here was a world where I could easily imagine myself as the hero, even though I can’t rhyme to save my life. Musically, both Dan the Automator and Kid Koala provided a soundtrack that managed to straddle the line between soulful throwbacks and futuristic intensity. Nothing in hip-hop sounded like this record!

Truly, the brilliance of Deltron 3030 was multifaceted. The complex future that’s spread over the album felt living, real, and frightening. Half the planet is an unlivable desert, populated by brain-eating cannibals. And the world that is tenable is controlled by a vicious military force, which is where the album’s hero, Deltron Zero, rises to the occasion. While referencing The Matrix, Ghost in the Shell, Metropolis, and other popular science fiction narratives, Del’s rhythmic lyrics portray the struggle between independence and fascism, violence and hope, self-determination and despair. And practically all of it works as a scathing indictment of the problems and issues that Del and his contemporaries were dealing with back in 1999 and 2000.

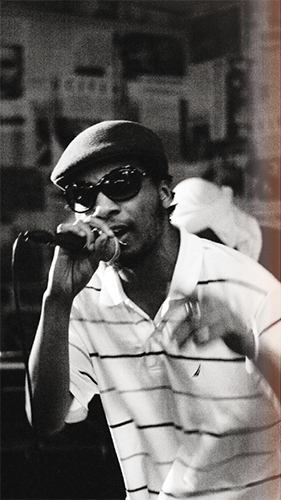

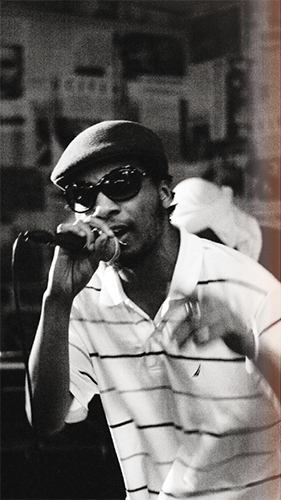

Deltron3030’s Del the Funky Homosapien.

Photo credit: Elliothtz.

I don’t know if it’s sad that, eighteen years later, the album is just as politically and socially familiar. It seems fitting, though, because Deltron 3030 is cyclical in nature. When “Memory Loss” hits and Deltron Zero loses his memory upon his return to Earth, we’re shown how the forces that hurt us repeat over and over, in large part because humans are so ignorant to the repetitive nature of history. Let Deltron 3030 be your lesson then. Let the sultry grooves and beats take you over as you immerse yourself in the intoxicating and invigorating experience of one MC’s fight against a dystopian world. It’s an album that rewards multiple listens, and it remains one of the more underrated albums in the genre—well, both the genres of hip-hop and science fiction. Get into it. *

The Science-Fiction Soundscapes of Porcupine Tree

Composer, singer, and guitarist Steven Wilson (b. 1967) founded Porcupine Tree in the 1980s as a solo project, but as the music found its footing as postmodern psychedelic prog rock, Porcupine Tree evolved into a genuine band. Their music is often experimental and ambitious, changing significantly from album to album. Their discography is incredibly varied, making them one of the era’s most difficult musical acts to classify. Writing for Rolling Stone, David Fricke called their music “an aggressively modern merger of Rush’s arena art rock, U.K. prog rock classicism—especially Pink Floyd’s eulogies to madness and King Crimson’s angular majesty—and the postgrunge vengeance of Tool.”

Despite the unpredictability of each new album from this innovative group, one clear uniting element is a preoccupation with outer space and the otherworldly, a thread running though their discography to date. These themes are perhaps most explicit on their first album, On The Sunday of Life (1991), when the band was still finding its footing, with over-the-top and occasionally parodic lyrics rife with lush and purple prose. The album includes acid-trip-ready tracks such as “Jupiter Island,” which evokes “magenta forests on a crimson sea, the electric clouds are as vivid as can be,” and “It Will Rain For A Million Years” (“I locked myself inside the capsule and watched the planet slowly turning blue . . .”). Perhaps the most over-the-top of all is the track “Space Transmission,” which purports to convey a message from someone who has been trapped on Planet Earth in darkness ever since the sun exploded fourteen years ago.

Porcupine Tree’s early albums also wear their Pink Floyd influence on their sleeves, paying homage to their prog rock progenitor through similar expansive soundscapes and psychedelic riffs. The SF Encyclopedia draws this comparison specifically with regard to The Sky Moves Sideways (1995), which “details a materially disintegrating world, but this apocalypse is so dreamily hallucinogenic as wholly to avoid the usual outré stylings of this manner of end-of-the-world music.”

Lightbulb Sun (2000) includes the fantastic track “Last Chance to Evacuate Planet Earth Before It Is Recycled,” which samples a recorded speech by the leader of the suicidal cult Heaven’s Gate, whose members believed themselves to be representatives of another dimension. Explaining the cult’s impending departure, its leader states, “Let me say that our mission here at this time is about to come to a close . . . We came from distant space . . . We are about to return from whence we came.”

Steven Wilson live on the To The Bone tour. Photo credit: Hajo Mueller.

Voyage 34: The Complete Trip (2000) also samples an existing recording, while continuing to riff on the concepts of inner and outer space. The found audio that serves as the backbone of this concept album reports on a young man’s bad acid trip in the 1960s. “It was an anti-LSD propaganda album,” Wilson said to Rolling Stone, “and it was perfect to form a narrative around which I could form this long, hypnotic, trippy piece of music.” Though primarily instrumental, the album nevertheless transports its listener into psychedelic planes.

Perhaps the best way to enjoy Porcupine Tree’s early, SFF-adjacent and influenced work is through their retrospective compilation album Stars Die, which collects some of the band’s best work from 1991—when it was really just Steven Wilson and a synthesizer—to 1997. It includes the fantastic tracks “And The Swallows Dance Above the Sun,” “Synesthesia,” “Stars Die,” “The Sky Moves Sideways,” “Fuse the Sky,” and “Dark Matter.” It’s the perfect soundtrack for an especially dark night watching the especially bright stars, dreaming of all the worlds that have long since died, even as on our own distant planet we continue to glimpse their long-lost light. *

LASHAWN M. WANAK

Metropolis Meets Afrofuturism:

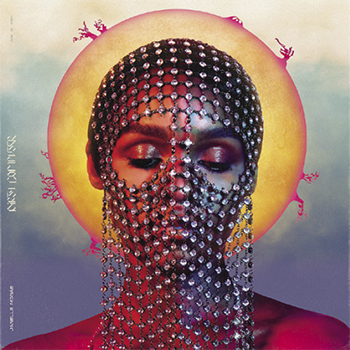

The Genius of Janelle Monáe

A dark alley behind an apartment complex in Neon Valley Street. Two figures running hand in hand, one human, the other android. The buzz of chainsaws and the crackle of electro-daggers. This evocative image begins the tale of Cindi Mayweather, spun in lyrical form by Janelle Monáe: songstress, poet, dreamer, prophet, feminist, Afrofuturist.

To listen to Janelle Monáe is to immerse oneself into an audio-cinematic experience. From her debut EP Metropolis to her current album Dirty Computer, Monáe’s songs sweep through genres with the ease of donning clothes: crooned ballads, punk rock screamfests, bubblegum pop, swelling orchestral arias, blistering rap. Through it all, science fiction wends like a pulsing heartbeat. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis influences the creation of Neon Valley Street, with Monáe adopting its titular poster image for her album cover of ArchAndroid. There are references to electric sheep, time travel, and a prophecy about a cyborg messiah who will unite the whole world.

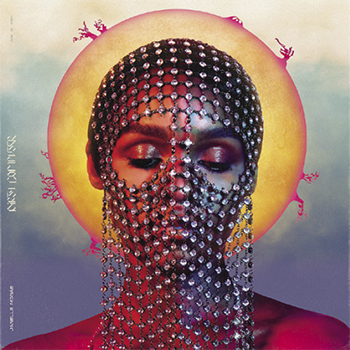

Named by NPR as the top album of 2018, Dirty Computer—Janelle Monáe’s third studio album—was showered with accolades by critics and fans alike. Rolling Stone called the accompanying 46-minute film (“emotion picture”) “a timely new sci-fi masterpiece,” exploring the way Monáe deploys classic science fiction tropes of enigmatic identity, fluid reality, and fascist dystopia in service of her own inventive mythology. Image credit: Atlantic Records.

“I thought science fiction was a great way of talking about the future,” Janelle Monáe told Bust Magazine in a 2013 interview. “It doesn’t make people feel like you’re talking about things that are happening right now, so they don’t feel like you’re talking down to them. It gives the listener a different perspective.”

But Monáe doesn’t just borrow science-fiction motifs. She rewrites them in Afrofuturistic terms that reflect her own experiences as a black, queer woman trying to survive in a world that sees little value in her. Metropolis and ArchAndroid particularly explore how androids are used as stand-ins for the marginalized and the oppressed. Monáe joins the ranks of other black music artists who have blended science fiction into their works: George Clinton/Parliament, Sun Ra, Missy Elliott. But Monáe stands out as having a single narrative span across several albums—that of Monáe’s alter ego, Android 57821, otherwise known as Cindi Mayweather.

Cindi Mayweather is an android who has committed the sin of falling in love with a human. Monáe tells her story in fragments, in music lyrics, and music videos. Throughout Metropolis, Cindi runs from bounty hunters, gets captured, and languishes in cybertronic purgatory. In the video for the song “Many Moons,” she is programmed to sing at an android auction, where she experiences a strange power that levitates her, then shorts her out. In ArchAndroid, she discovers that she may be the archangel who could save the world. In the video for “Tightrope,” a tuxedo-clad Cindi causes an almost-successful rebellion in The Palace of the Dogs asylum. In The Electric Lady, considered a prequel to ArchAndroid, Cindi is still on the run, known as Our Favorite Fugitive.

The story is fragmented, and may in some cases contradict itself, but Monáe keeps it going by framing the narrative in suites numbered I through V (much like a science fiction series). She also fleshes out Cindi’s story through music videos, liner notes, Websites, motion picture treatments (music video concepts in written form), and even short films and fan art put out by Monáe and her producers at Wondaland Records. All of this is woven into a cohesive narrative that not only works, but also gives glances into a richer world full of intrigue, drama, love, loss, and revolution.

Monáe’s use of Cindi Mayweather brings to mind Ziggy Stardust, David Bowie’s alter ego and subject of his fifth album, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. His album features a bisexual, androgynous being who was sent as a messenger from extraterrestrials and is used by Bowie to explore sexual themes and social taboos. In Bowie’s case, however, he did not want to be continually defined by Ziggy and dropped the persona. Janelle Monáe could have done this as well, but rather than fade Cindi May-weather into obscurity, Monáe chose to continue the narrative of Android 57821 by taking a new direction—utilizing clones of herself.

Monáe’s clones populate her album covers and videos: strutting at android auctions, serving as waitresses and newscasters, dancing in unison, causing small rebellions that fail. Some of these clones have names—the album cover of Electric Lady is depicted as a painting of Cindi Mayweather and her “sisters”: Andromeda, Andy Pisces, Catalina, Morovia, and Polly Whynot. Monáe can then shift her narrative while remaining in keeping with the android universe she’s created. This is most prevalent in Dirty Computer, where we are introduced to Jane 57821, who shares the same number as Cindi Mayweather, but is older, less naïve, and more of a revolutionary than a messiah. This reflects Monáe’s own change as she becomes more open about her pansexual identity, as well as responding to the #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo movements. Even the music style shifts from the angelic crooning of Cindi Mayweather in ArchAndroid to the throatier rasp of Jane/Janelle in Dirty Computer.

Janelle Monáe’s work reinvents the boundaries of identity performance with herself as the fictional and ever-evolving character at the story’s center. (The comparisons to David Bowie are unavoidable.) In The New Yorker, Doreen St. Félix wrote in 2018 that the artist “has taken the concept album to complex heights.”

It’s a brilliant strategy. In having multiples selves, Monáe can expand upon the worldbuilding of her narrative, told in multiple viewpoints but all originating from herself. She is not locked into a single narrative, but is able to explore all facets of her self-identity, from her queerness to her blackness to her religious faith. This makes Monáe not only an excellent musician, but also an amazing storyteller, one who is telling a science fiction story in real time.

In her SyFy Wire article “Octavia Butler and America as Only Black Women See It,” Tari Ngangura wrote, “It is a rare writer who can use sci-fi not simply to chart an escape from reality, but as a pointed reflection of the most minute and magnified experiences that frame and determine the lives of those who live in black skin.” Through her music, the story of Cindi Mayweather/Django Jane/Janelle Monáe is bringing people who have been in separate worlds—science fiction enthusiasts, the hip-hip community, queer folk—and uniting them in a shared universe just as diverse as her musical styles.

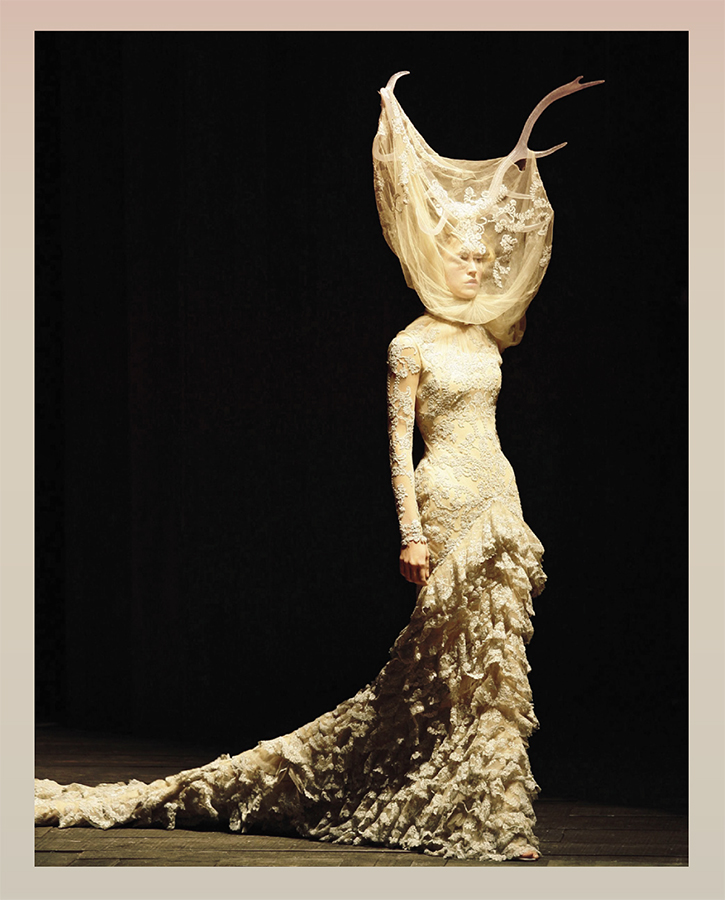

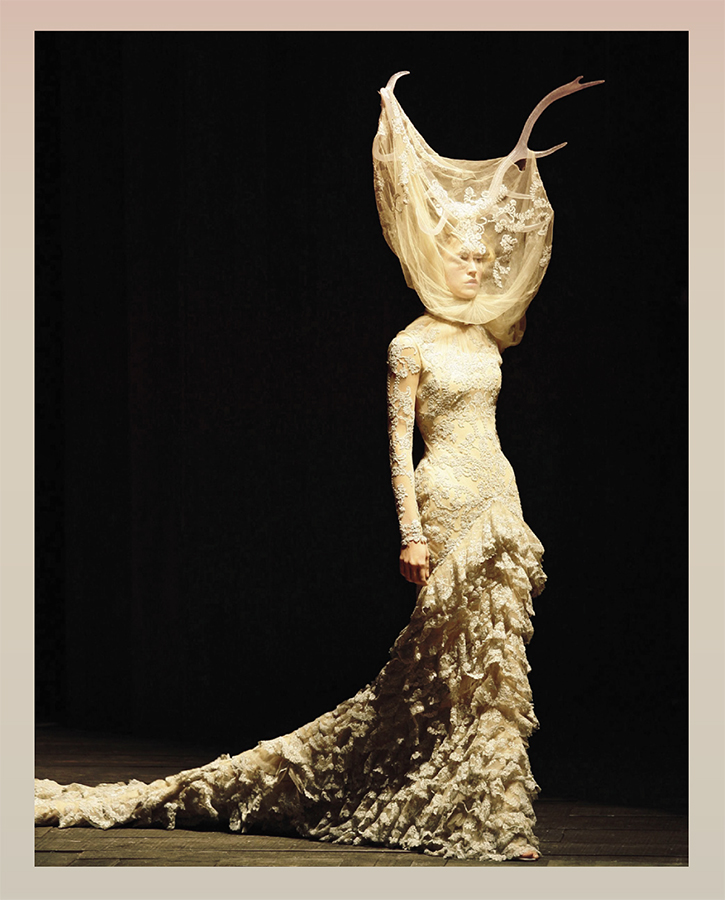

A model on the runway at Alexander McQueen’s fall 2006 show at the Palais Omnisport de Paris Bercy. Photo credit: Giovanni Giannoni/Penske Media/Shutterstock.