FANDOM AND POP CULTURE

SFF fans have always been particularly enthusiastic participants in their favorite genre, often with strong and passionate opinions about what science fiction and fantasy is and should be. We aren’t just fans . . . we’re fandom. And we change, shape, and grow the genre as actively as it changes us.

Sometimes those movements are right out in the open. Other times they’re tectonic, big waves beneath the surface that only show their impacts much later—such as the fan fiction influences that pointed the way to a new kind of storytelling for two contributors. Or these movements are tangential at first, odd bits of pop culture lore, which like the Illuminati or the Voynich manuscript, slowly weave their way into science-fiction storytelling.

One thing is for certain—science fiction is culture, and culture is science fiction. (Or as Thomas M. Disch put it, science fiction is “the dreams our stuff is made of.”) This chapter explores some of those lesser known interconnections . . . and how the active, participatory nature of SFF fan culture can bring them to the surface.

The Surreal Potential of the World’s Most Mysterious Manuscript

There are a few things we know almost definitively about the Voynich manuscript. We know that it dates back to the fifteenth century and was created somewhere in Central Europe. We know it was once owned by Emperor Rudolf II of Germany (1576–1612), who reportedly purchased it for 600 gold ducats, which sounds like a lot. We also know that it is named after Wilfrid Voynich, the eccentric bookseller who acquired it in 1912.

The rest—the manuscript’s origin, its history, its meaning—are shrouded in mystery.

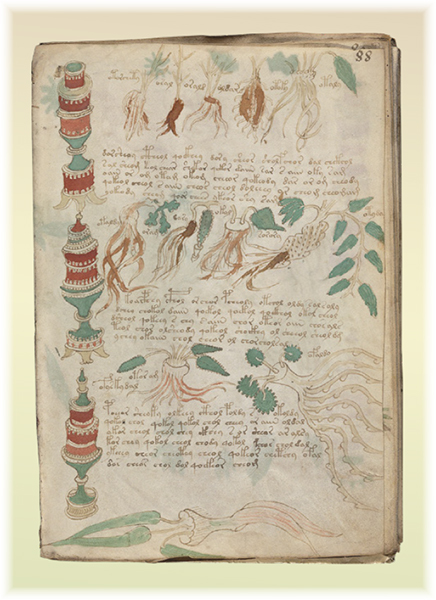

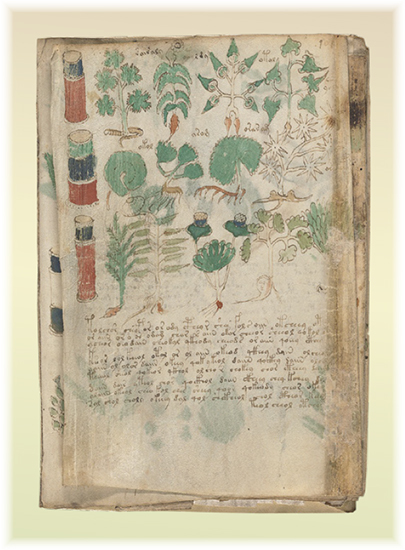

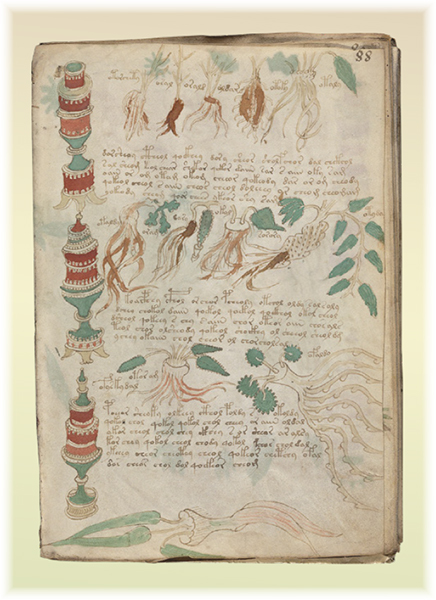

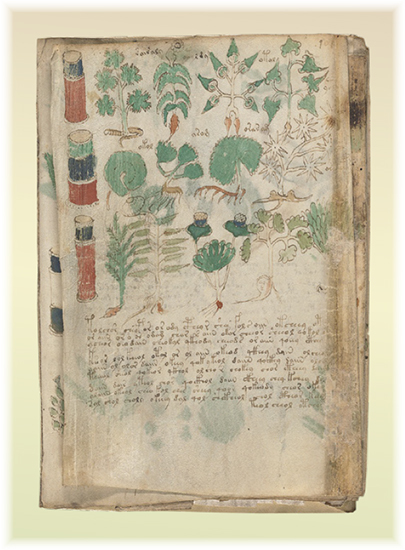

The manuscript combines looping, handwritten text written in an unknown and probably invented language with bizarre botanical and figurative drawings of 113 nonexistent flowers, roots, and herbs; nude females in a variety of situations; pipes, chimneys, and tubes; and astrological and cosmological charts and symbols. Voynich enthusiasts typically divide the book into four sections—herbal, astrological, pharmacological, and balneological (a word that refers to the study of therapeutic bathing, and should really be used more often). Through the manuscript’s entire history, the text has remained indecipherable, and the surreal drawings are equally enigmatic.

Likewise, the manuscript’s full history is a mystery. It is not clear who Emperor Rudolf purchased it from, though it may have been the English mathematician and alchemist John Dee (1527–1608). Possibly, Emperor Rudolph believed the manuscript to be the work of Roger Bacon (1220–1292), an English philosopher. For a time, contemporary Voynichologists also theorized that Bacon was the author, although this has since been debunked. The manuscript passed hands a few times after that. Its last known location was with Athanasius Kircher (1701–1680) in 1666. Then it disappeared from the historical record until Wilfrid Voynich obtained it from a Jesuit college near Rome in 1912.

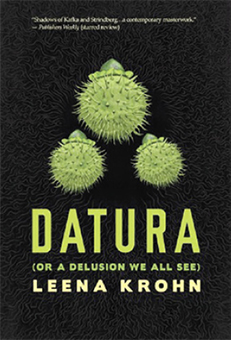

Originally published in Finnish in 2001, Leena Krohn’s Datura appeared in English for the first time in 2013 with a publication by Cheeky Frawg Books, translated by J. Robert Tupasela and Anna Volmari. In a starred review, Publisher’s Weekly praised the 2013 edition with the words “aficionados of the surreal will find this a contemporary masterwork.”

All images from the Voynich manuscript are courtesy of Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, where the “cipher manuscript” resides under call number Beinecke MS 408.

Voynich was quite the colorful character himself. Born in 1864 Lithuania (in what was then the Russian Empire) to a Polish family, he was impressively multilingual, reportedly speaking twenty languages. He was a social revolutionary and a member of the Proletariat Party, which earned him a sentence without trial and a five-year exile to Siberia. He escaped from Siberia, bartered his way onto a boat, and made it to England, where he continued to rub shoulders with the political and intellectual counterculture and became a successful book dealer.

When a group of Jesuits decided to sell some of their library to the Vatican, Voynich traveled in secrecy to Rome and purchased some of the collection first—including the Voynich manuscript. He believed, or claimed to believe, that the manuscript was a tome of black magic, with “discoveries far in advance of twentieth-century science.”

Considering Voynich’s fascinating persona, and the fact that he once sold the British Museum a forgery, it was once hypothesized that the entire manuscript was a hoax fabricated by Voynich himself. However, carbon dating offers solid evidence that it definitely dates back to the Middle Ages. (Unless Voynich somehow obtained a large quantity of blank vellum from the early fifteenth century—implausible, but not absolutely impossible.) If it is the work of a practical jokester, the jokester in question most likely hailed from much more antiquated times.

Historians and Voynichologists have proffered dozens of theories as to the book’s original authorship, but none have been proven. Likewise, cryptographers and codebreakers have spent the past one hundred years attempting to make meaning of the book’s unknown and enigmatic language. As William Sherman writes in “Cryptographic Attempts,” an essay that accompanies Yale’s recent facsimile of the manuscript, “The quest has also exercised the minds of some of the greatest code breakers in history.” Sherman goes on to detail some of these attempts, including work by William F. Friedman, “who would spend several decades as the U.S. government’s top maker and breaker of codes.”

Of course, attempts to crack the code are not only the domain of army cryptographers and scholarly medievalists. There are a hundred flourishing Internet communities and discussion groups where hobbyists and obsessives hash out a million theories of varying degrees of plausibility. Every few years, someone claims to have finally “cracked the code”—only to be refuted by their fellows. One of the first of these was William Romaine Newbold, a historian of medicine and philosophy. He announced his “breakthrough” in 1921 and went on a short but intense lecture tour. By 1928 his supposed cipher had been destroyed by skeptics and critics who pointed out his biases and errors.

These kinds of breakthroughs and retractions have happened a number of times over the past century. As recently as 2017, the Times Literary Supplement, a plenty reputable source, published an article by television researcher Nicholas Gibbs, who announced with no small modesty that he had finally found the solution. He’d identified certain common abbreviations of Latin words and then—following a circuitous chain of reasoning—concluded that the Voynich manuscript is in fact “a reference book of selected remedies lifted from the standard treatises of the medieval period, an instruction manual for the health and wellbeing of the more well to do women in society, which was quite possibly tailored to a single individual.” The news spread quickly across the Internet, receiving glowing and credulous coverage on just about every pop culture blog there is, until experts weighed in with their knowledge of medieval literature. Their assessment: This makes no sense at all.

Perhaps the world’s most mysterious manuscript will never be explained; perhaps it’s better that way. We all need some mysteries, after all. As Josephine Livingstone wrote in The New Yorker, “Whether code breaker or spiritualist or amateur historian, the Voynich speculators are linked by their common interest in the past, quasi-occult mystery, and insoluble problems of authenticity. . . . This single, original manuscript encourages us to sit with the concept of truth and to remember that there are ineluctable mysteries at the bottom of things whose meanings we will never know.”

Leena Krohn, a remarkable writer of Finnish weird fiction, draws on these themes in her novel Datura, which features the Voynich manuscript as a through-line and a touchstone. The novel’s narrator works as an editor and writer for The New Anomalist, an obscure magazine that specializes in the occult and paranormal. One of the subjects she’s intended to cover is the Voynich manuscript, which she encounters for the first time with the typical bafflement: “It looked medieval and was richly illuminated: symbols, maps, circles, celestial bodies or maybe cells, it was impossible to know. Naked women with rosy cheeks bathing, and animals of unknown species, possibly frogs, salamanders, fish, cats, lions . . .” But our narrator has also begun dosing herself with the toxic seeds of the datura plant in an attempt to treat her asthma. Datura poisoning causes hallucinations, and as the story goes on, she finds herself increasingly untethered from reality.

But what is reality, anyway? That’s what the narrator begins to question—and as aficionados of the inexplicable parade through her editorial offices, the answer grows ever less clear. She says, “This is what I think I’ve learned: Reality is nothing more than a working hypothesis. It is an agreement that we don’t realize we’ve made. It’s a delusion we all see.”

If reality is a shared delusion, then perhaps the Voynich Manuscript is merely an artifact from another history’s waking dream. As the narrator’s connection to our own world grows more tenuous, it all seems like a hallucination, real and unreal. Toward the end she writes, “I wake up as if from another dream and look around myself for the first time. At times like that, all books are like the Voynich manuscript to me: ciphers, cryptographies, beyond all interpretation.”

Krohn is far from the only storyteller to be inspired by the enigma of an unreadable book. The Voynich manuscript, or documents like it, has shown up in a multitude of works, particularly speculative ones. Another popular writer who was influenced by it is novelist and historian Deborah Harkness. As a doctoral student, Harkness studied the library of John Dee, who may have been one of the earliest owners of the Voynich manuscript. She’s maintained a lifelong interest in the document, and a fascination with the mysterious and enigmatic that informs her fiction. Indeed, the narrative of her New York Times bestselling All Souls trilogy (which begins with A Discovery of Witches) hinges on the discovery of a rare manuscript.

In her introduction to the Yale facsimile, Harkness wrote of her first experience seeing the manuscript in the flesh, at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, where it goes by the moniker Beineke MS 408. “Perhaps my reaction to the Voynich manuscript was shaped by the fact that my interest in it was no longer as a Dee scholar but as a novelist. I don’t know what I expected, but at first glimpse it was oddly anticlimactic: small, worn, and drab outside; cramped and confusing inside . . . At the same time, I could not stop turning the pages. . . . And yet the more minutes I spent with it the more I suspected that all the time in the world would not make the Voynich manuscript yield its secrets—at least not to me.”

SELENA CHAMBERS

Celebrity Robots of the Great Depression

The United States during the 1930s is not exactly known for its automatons, but in-between the Crash and the New Deal, four humanoid robots toured the country and became Great Depression Rock Stars. First to set the stage was Britain’s Eric the Robot, who debuted in 1929 at an exhibition of the Society of Model Engineers in London as a speaker replacement for the Duke of York. Built by Captain William Richards and Alan Refell, Eric’s appearance was like an armored knight, and activated by voice control, he rose from his bench, bowed to the audience, and gave a four-minute address while turning his head, gesturing with his hands, and emitting blue sparks from his teeth.

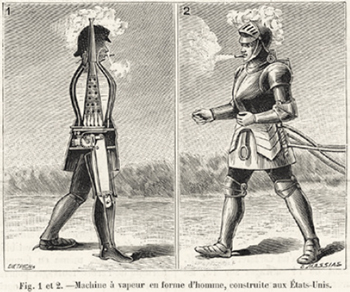

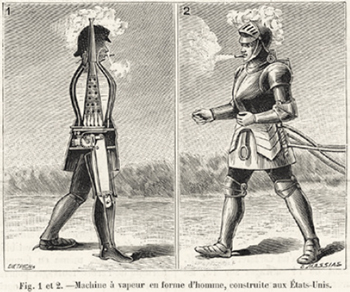

George Moore’s Steam Man (1893) by Georges Massias, an illustration of a steam-powered robot built by Canadian inventor and professor George Moore. The robot was life-size and exhibited widely.

After this famous premiere, Eric brought his mechanical chivalry to the United States, where he mysteriously disappeared. Richards replaced him with an improved second effort in 1930: George, whose multi-language program garnered him the reputation as an “educated gentleman” compared to “his rough-hewn awkward brother” in the press. Despite his gentle status and engineering advancements, George, too, vanished into the scrapheap of the unknown.

By 1934, audiences craved a more common man, and they got it with badboy Alpha. Also Britain-born, not much is known about this ruffian automaton with long metallic curls, other than he shot blank revolvers and cracked-wise with doe-eyed dames. Before he landed in the U.S., his reputation was preceded as a Frankenstein-like creature who shot his creator, Harry May, upon activation. Surely, this false rumor didn’t hurt ticket-sales.

Elektro, the cigarette-smoking robot. Image courtesy of the Mansfield Memorial Museum.

By the end of the thirties, the U.S. had seen many a foreign robot come and go, but none successfully captured a generation’s imagination like Elektro the Moto-Man. Built by the Westinghouse Electric Corporation in Mansfield, Ohio, he was the U.S.’s first homegrown humanoid. With a seven-foot-tall gold-brushed aluminum body and color-differentiating photoelectric eyes, Elektro’s stage presence seemed magical to the 1939 New York World’s Fair attendees.

Millions waited three hours to catch Elektro’s twenty-minute acts, where he walked the stage, taunted audience queries with provocative responses like “My brain is bigger than yours,” counted on his fingers, and made jokes about operator errors. The real crowd pleasers were when he smoked cigarettes and blew up balloons.

But there was no legerdemain present in Elektro’s performance, just a composition of the latest and greatest technologies. Under his golden aluminum skin was a metal skeleton containing camshafts, gears, motors, and a bellows system for lungs. His 700 word vocabulary was provided by a 78 rpm record player and was composed of forty-eight electrical relays that controlled the eleven motors that prompted his speech and twenty-six movements—all under voice control commands transmitted via telephone relay.

While all of his predecessors had been scrapped for war or disappeared, he enjoyed a much longer presence in the public eye, although it also became diminished over time. By the 1950s, Elektro went on revival at in-store promotions for all Westinghouse departments. He even dabbled in acting, appearing as Sam Thinko in the B movie Sex Kittens Go to College, receiving stripteases from Vampira and Mamie Van Doren.

Eventually, Elektro retired at the Palisades Park in Oceanside, California and the fervor and enthusiasm he once enjoyed as “America’s first celebrity robot” only remains in the black-and-white print of old newspaper and museum docent accounts. For those who want to relive the glory of the Moto-Man, a pilgrimage can be made to Ohio’s Mansfield Memorial Museum, where Elektro’s head and torso reside in its archive.

The Historical and Literary Origins of Assassin’s Creed

Assassin’s Creed is one of the top-selling video game franchises of all time, with eleven major games in the franchise as of 2018, and many more spin-offs. There was even a 2016 movie called Assassin’s Creed.

The powerful franchise began in 2007, when the first game launched for PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360. But we can trace the concept’s genesis much further back . . . to an obscure novel titled Alamut, published by Slovenian writer Vladimir Bartol in 1938, and its historical influences: eleventh-century Persia (today’s Iran), and real events that have been blurred by legend.

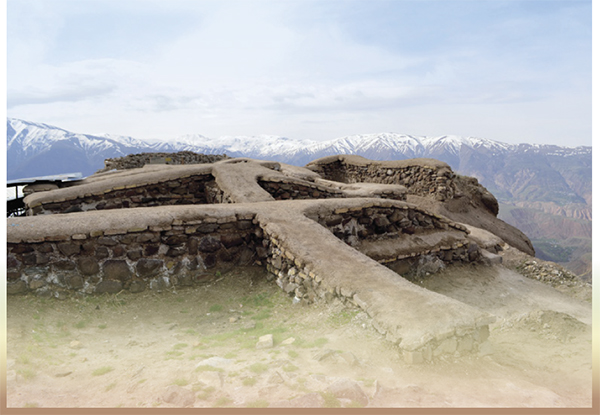

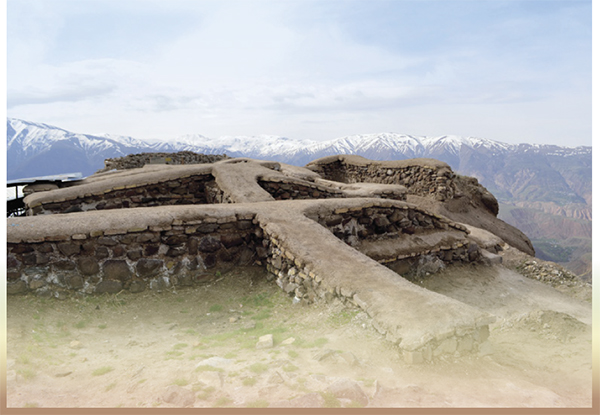

A 2014 photo of the remains of Alamut Castle in the Alborz (Elburz) Mountains, northern Iran. Photo credit: iStockphoto/ivanadb.

The ruins of Alamut Castle. Photo credit: iStockphoto/uskarp.

The novel is a fictional retelling of the founding of an Islamic order of assassins; it’s also a commentary on fascism and totalitarianism, and the techniques that demagogues use to control their followers and manipulate the public. At the time of its writing in the 1930s, Europe was on the verge of crisis. Croatian and Bulgarian nationalists had just assassinated Yugoslavia’s King Alexander I—perhaps at the behest of the fascist government in Italy. The ugly fervor of nationalism was taking hold across the continent. World War II was just a few years away.

Much like the magical realist authors of Central and South America, Bartol evaded censorship by cloaking his criticism in a fantastical tale, creating a world that on the surface might have seemed much different from his own, but when you read between the lines, there were plenty of similarities. Bartol even dedicated the novel to Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, a delicious bit of irony and politely cast shade.

Bartol did his research. In fact, he spent a decade learning about the history underpinning the legends of the assassins, and studying the religious and cultural context.

At the center of Alamut is real-life Ismaili leader Hassan ibn Sabbah, who built a hilltop fortress called Alamut and created an elite squad of suicide attackers called the Assassins. Sabbah convinced his young warriors that paradise awaited them if they sacrificed themselves. He called his fighters “his living daggers.” He rewarded them with drugs, booze, and beautiful women.

This historical reality was embellished generously by the Italian explorer Marco Polo, who reported the sect’s existence to his fans back home. He may have exaggerated the full extent of the debauchery—there is some scholarly debate about whether his reports of drug use were totally accurate—but the sect’s existence is confirmed, as well as their strategic political and religious assassinations. The ruins of their castle fortress, perched atop a massive mountain of rock, can still be seen today.

Bartol’s Alamut is mostly told from the perspective of a young warrior named Ibn Tahir and a slave girl named Halima. Tahir assassinates a handful of Sabbah’s rivals, leaders of competing sects. But he begins to turn against Alamut. Eventually he confronts Sabbah, who invokes the creed, “Nothing is an absolute reality, all is permitted.”

In Assassin’s Creed, those lines become “Nothing is true, everything is permitted,” a manifesto that links the game’s many iterations and installments. (William S. Burroughs also appreciated the line, which he used in Naked Lunch.) And the storyline of the first Assassin’s Creed game also contains some parallels with Bartol’s novel and the historic assassins, adding a dose of alien technology and other weirdness.

The novel found its fans here and there throughout the twentieth century, particularly in the war-torn Balkans of the nineties, where its themes of totalitarianism and zealotry struck home. Still, it was mostly forgotten until 2001, when Al-Qaeda’s 9/11 terror attacks sparked the American public’s interest in the motives of violent extremists. The real-life story of Alamut and the hashshashin (or assassins) seemed as if it might be relevant. Perhaps this 1938 novel that fictionalized eleventh-century Persia as a commentary on fascist Europe could offer some insight into the minds of twenty-first-century terrorists from Saudi Arabia?

Alamut enjoyed a brief renaissance and was translated into many more languages, and was published for the first time in English in 2004. A few years later, the first Assassin’s Creed (2007) would be released to wide acclaim.

Judging from geopolitics, Alamut’s insights could neither solve the problem of terrorism, nor prevent the rise of fascist ideologues of any stripe. But its rich setting and compelling story may have helped to inspire a game with a powerful central narrative that continues to fuel a massive and successful franchise.

Jack Kirby, the King of Comics

Just about every pop culture fan is familiar with Stan Lee (1922–2018), whose name is practically synonymous with Marvel Studios and the midcentury’s comic book revolution. And while Stan Lee—who famously admitted he’d “take any credit that wasn’t nailed down”—undoubtedly made enormous contributions to the genre, they were equally rivaled by those of his less-famous co-creator, Jack Kirby (1917–1994). As dedicated comic fans pay tribute to Kirby’s contributions, he’s never quite become a household name. The characters he invented are another story. As journalist and comics critic Jeet Heer writes in The New Republic, “If you walk down any city street, it’s hard to get more than fifty feet without coming across images that were created by Kirby or inflected by his work. Yet if you were to ask anyone in that same stretch if they had ever heard of Kirby, they’d probably say ‘Who?’”

In fact, Kirby was instrumental in developing the pantheon of superheroes currently filling theaters for summer blockbusters and fueling new forms of extended storytelling via Netflix’s shows in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. His characters include Captain America, the Hulk, the X-Men, the Fantastic Four, the Avengers, and the Silver Surfer. He was both a storyteller and an artist, creating memorable storylines at the same time as he developed a unique and highly recognizable visual vernacular for superhero comics, bringing an energy and dynamism to the art that was previously lacking. He was massively prolific, creating an estimated 20,000+ pages of published art and 1,385 covers throughout his career.

Born to immigrant parents, Kirby grew up in a working class Jewish neighborhood in New York’s Lower East Side. (His birth name was Jacob Kurtzberg; he began signing his comics Jack Kirby and later changed his name legally.) Both his Jewish heritage and his impoverished upbringing were essential aspects of his identity. As a child, he often participated in one of the neighborhood kids’ favorite form of recreation: fighting. According to Rand Hoppe, curator of the biggest collection of Kirby images online, “Jack loved fighting so much that he once took a long subway trip to the Bronx to see if they fought any differently there.” His first-person experience of hand-to-hand combat later proved immensely valuable as he choreographed and illustrated superheroes fighting for justice in the mean streets of New York.

Kirby enrolled at Pratt Institute to study art, but only lasted a week—they weren’t interested in his artistic style and he couldn’t afford the tuition anyway. Instead, he found work at an animation studio, honing his skills as a draftsman doing gruntwork on cartoons like Popeye and Betty Boop. He moved into comics and worked on newspaper strips. It was then he began signing his name as Kirby.

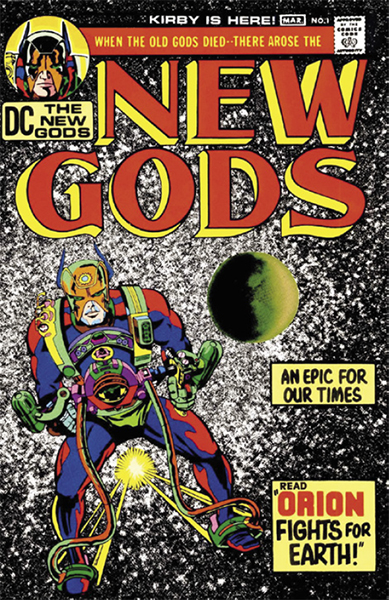

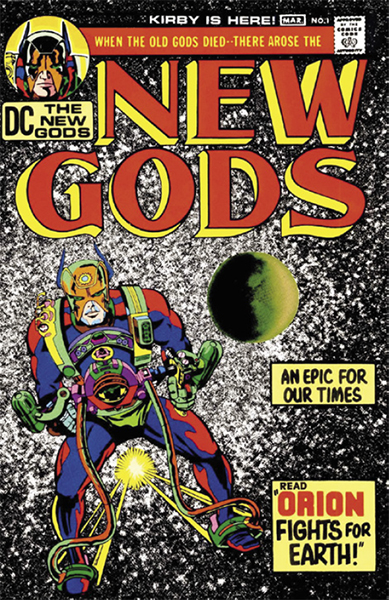

New Gods #1 © DC Comics. The opening volume of Kirby’s Fourth World series was published in 1971 and introduces characters Highfather, Lightray, Metron, and Orion. Image courtesy of DC Comics.

Soon, Kirby went into business with Joe Simon, who he’d met in the comics business. The two of them formed their own studio and began developing multipage comics. One of the earliest of these was Captain America. This patriotic, flag-flaunting hero made his arrival in 1940, a year before America entered World War II. The cover of the first issue depicted Captain America punching Adolf Hitler in the face.

It’s important to understand the cultural context here. While the United States’ selfhagiography of its actions in World War II portrays a nation united against the Nazis, the reality was quite different. Then, as now, the United States was home to an appallingly large contingent of fascist and Nazi sympathizers. For their bold repudiation of Nazism, Simon and Kirby received enough death threats from fellow Americans that the police had to intervene. In his biography of Kirby, Mark Evanier describes one notable occasion: “Jack took a call. A voice on the other end said, ‘There are three of us down here in the lobby. We want to see the guy who does this disgusting comic book and show him what real Nazis would do to his Captain America.’ To the horror of others in the office, Kirby rolled up his sleeves and headed downstairs. The callers, however, were gone by the time he arrived.” It’s safe to assume that Kirby would certainly have punched those Nazis himself, if he got a chance.

In 1943, Kirby was drafted to fight in World War II. During the war, his commanders utilized his drawing skills (as well as his ability to speak Yiddish) and sent him into enemy territory to scout and draw maps. He remained traumatized for life by the horrors he observed during this time, and that brutality—as well as an all-stakes fight between good and evil—undoubtedly influenced the stories he told in the years to come.

Kirby’s most prolific years came in the 1960s, during his collaboration with Stan Lee. The two worked ferociously to put Marvel Studios on the map, beginning with the Fantastic Four, which was a smashing success. The “Marvel Method” emerged, a stark contrast to how comics were typically created. Stan Lee, as the only writer on the team, would offer a very generalized outline, developed through a freewheeling discussion with Kirby, who threw out plenty of plot ideas. The artists would get to work, creating the panels. (Along with Kirby, Steve Ditko was one of these artists, and he also made really significant contributions.) This approach offered artists a lot of control over how the story was told—they made critical decisions on pacing and plotting. Then Lee would fill in the dialogue. Other studios had writers creating a complete script before handing it off to the artists.

Concept art for a film based on Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light, designed by Jack Kirby and screen-writer Barry Ira Geller, and drawn by Kirby, with color later added by Heavy Metal Media, LLC. While the film was never made, the CIA used the concept art—and the movie-shooting—as a cover story to rescue six U.S. diplomats in Iran in 1979. The story is dramatized in the film Argo.

The Marvel Method led to innovative and dynamic work, encouraging the story to evolve organically and letting artists participate more fully in the storytelling; it was an ideal format for Kirby, both an avid storyteller and an inventive artist, to grow and thrive. The method also created a number of problems, because it was not totally clear who contributed what to the end product. Conflicts over authorship eventually soured the partnership between Kirby and Lee; a sad turn of events, because each of them did their best work while under the other’s influence. As novelist Jonathan Lethem writes, “Lee and Kirby were a kind of Lennon-McCartney partnership, in several senses: Kirby, like Lennon, the raw visionary, with Lee, like McCartney, providing sweetness and polish, as well as a sense that the audience’s hunger for ‘hooks’—in the form of soap-operatic situations involving romance and family drama, young human characters with ungodlike flaws, gently humorous asides, etc.—shouldn’t be undernourished.”

The work that emerged from Kirby and Lee’s collaboration remains the foundation for much of what Marvel is still producing today. “The great Kirby and Lee comics of the 1960s were pivotal in remaking superhero comics into something more than children’s fables, and one fundamental addition was the concept of a super-hero team,” writes Heer. Under their influence, comics became more than action; they became vehicles for a powerful mythology. “Operatic, sprawling, and mythopoetic, the stories Kirby and Lee worked on remade superhero comics into a form of space opera, taking place in a teeming, lively, and imaginatively exciting universe.”

Nevertheless, Lee and Kirby’s irrevocable split over authorship and royalties was made more acrimonious by what Kirby saw as Lee’s grandstanding. (A 1965 newspaper profile of the two that characterized Lee as “ultra-Madison Avenue” and Kirby as “the assistant foreman of a girdle factory” certainly didn’t help.)

In 1970, in the aftermath of this breakup, Kirby shocked the entire comics world by making a switch to Marvel’s number one rival: DC. This move was motivated in part by DC promising Kirby full creative control over his own stories. There he embarked on his most ambitious work yet. This series of titles, called The Fourth World comics, included Mister Miracle, The New Gods, and The Forever People. It was a complex and sprawling epic, overflowing with interwoven threads and dancing across genres—the innovative work of an auteur given free rein to explore his most genuine artistic impulses. Lethem describes it as “massively ambitious, and massively arcane.” To DC’s disappointment, it was not a commercial success.

“At DC, Kirby seemed to have flown off into his own cosmic realms of superheroes and supervillains without any important human counterparts or identities,” Lethem says. “The feet of his work never touched the ground. The results were impressive, and quite boring.”

Storytelling aside, it’s not just his prolific creation of characters that earned Kirby the title the “King of Comics.” His vibrant, boisterous, highly stylized illustrations influenced a generation of comic book artists. He pioneered foreshortening techniques, a part of the scene thrusting into the immediate foreground, bringing more depth to previously flat images. “There was something special about any story with Kirby art,” writes biographer Mark Evanier in his Afterword to Kirby: King of Comics. “His work fairly crackled with life-affirming energy. Even with the bad printing and the sometimes-bad inking, it commanded your attention and your involvement.”

Likewise, Kirby’s intricate depictions of machines and technology—such as his rendering of Black Panther’s futuristic techno-utopia of Wakanda—inspired creators like James Cameron, who called Kirby “a visionary.” Cameron said of his own work on Aliens: “Kirby’s work was definitely in my subconscious programming. . . . He could draw machines like nobody’s business. He was sort of like A. E. van Vogt and some of these other science-fiction writers who are able to create worlds that—even though we live in a science-fictionary world today—are still so far beyond what we’re experiencing.”

Valérian, the Popular French Comic Series That Inspired a Generation

The Fifth Element (1997) is one of those delightfully polarizing movies that people seem to either love or hate; it’s a weird spectacle, a baroque fever dream, both surreal and unforgettable. The narrative centers on an ancient alien evil that threatens to destroy a twenty-third century Planet Earth. The only weapon that can defeat it is comprised of four stones (expressing the classic elements, earth, water, air and fire) . . . plus Milla Jovovich. This narrative is often baffling and occasionally incoherent, but is carried by the charismatic performances of Gary Oldman, Chris Tucker, and a ruggedly handsome and wisecracking Bruce Willis, playing that guy he always plays—you know the one. A red-headed, waiflike Milla Jovovich is breathtakingly beautiful, making her status as the most supreme being on the planet a little easier to accept.

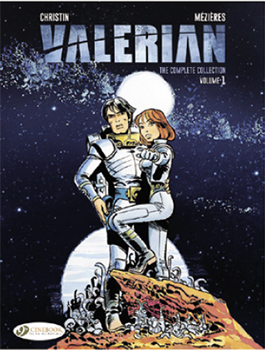

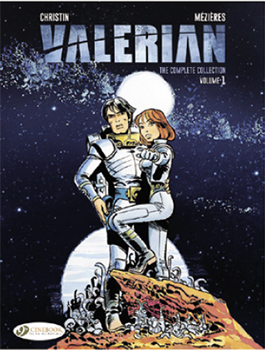

Valerian: The Complete Collection Volume I, which contains The City of Shifting Waters and The Empire of a Thousand Planets. Published by Cinebook in 2017.

The film’s greatest appeal is in its sheer spectacle. It’s bizarre, exuberant, occasionally grotesque, a boisterous pastiche. As pop culture critic Emily Asher-Perrin wrote in a review for Tor.com, “It is loud and dark, funny and frightening, heavy-handed but full of mesmerizing and carefully rendered detail. It is the cinematic equivalent of Rococo artwork, of New Year’s Eve fireworks, of a gorgeous rainbow cocktail that gives you the worst hangover of your life.” Back in 2000, film critic Adam Smith wrote for Empire, “This is a film that looks unlike any you’ve seen before. Ever.” Arguably, the descriptions still stands.

The film’s director, Luc Besson, hired fashion designer Jean Paul Gaultier to create the over-the-top costumes. He also called on several immensely talented consultants to aid in the design of the film. One was Jean Giraud, the famous French concept artist and illustrator who also went by Moebius (see this page). The other was Jean-Claude Mézières, co-creator of the long-running smash-hit graphic novel, Valérian et Laureline, which chronicles the adventures of two time-traveling government agents. Valérian, the time-traveling space agent, meets and is saved by a peasant girl in eleventh-century France, who then joins him on his journey, traveling to the twenty-eighth century to become his partner.

Mézières’s presence on the film was no coincidence. Besson had long dreamed of making these beloved French comics into a movie. In fact, he’d been a fan as a child, as the series first began in 1967. In 2016, he told an audience at San Diego Comic-Con that he began reading the comics when he was ten. “I wanted to be Valérian,” he said, “but I fell in love with Laureline.” Despite being a lifelong fan, Besson couldn’t see a plausible way to make the movie. Valérian, a grand intergalactic space opera about time-traveling space agents, was not the kind of story one could easily film. Until, of course, CGI changed the game.

Besson credits James Cameron’s Avatar with giving him the courage to finally tackle this project, his lifelong dream. “I thought to myself that the technology to make it was perhaps finally there. I’d already written several drafts of an adaptation a few years before then, but it was Avatar that made things possible.”

Without any major studio backing, Besson assembled the funding himself, coming up with around $200 million to finally bring Valérian to the big screen—the most expensive non–U.S. studio movie ever made. Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets hit theaters in summer of 2017. Fans of The Fifth Element were elated, ready to once again enjoy a space opera extravaganza brought to them by the brilliant imagination of Luc Besson.

The Avatar influence is obvious from the first moments of the film, which depict the idyllic island paradise of the alien Pearls, who are bald, slender, graceful, and almost translucently pale (and slightly blue-tinged, though maybe that’s just the reflection of the sky and sea). Like The Fifth Element, the film is a massive visual spectacle, vibrant and frenetic, a million colors at once. Almost all of it is CGI. One of the earliest examples is a scene set in absolutely massive inter-dimensional market, an entire world somehow folded inside the atoms of ours. Writing for Vanity Fair, Richard Lawson calls the scene “an absolute marvel, clever and kitschy and suspenseful.”

But Valérian’s sparkling eye candy and bizarre set pieces, while entertaining, feel entirely tangential to the story—and go on so long it becomes impossible to tell what the story is. “To pretend that there’s a plausible or comprehensible narrative line to the film would be a punishable misrepresentation,” wrote an unimpressed reviewer in the Hollywood Reporter (the trade paper wasn’t a fan of The Fifth Element, either). One notable example is Rihanna portraying a shape-shifting “glampod” who, for some reason, treats our reluctant hero to several long minutes of exotic dance. There are deeply problematic aspects to some of the alien representations, which are offensive in much the same way as The Phantom Menace’s worst offenders—with twenty years to do better. There is also a hearty helping of misogynist dialogue and a side of sexual harassment on the job, which comes across even more awkwardly because of the complete lack of sexual chemistry between the two leads.

It’s a shame the movie didn’t turn out better. But it did introduce the comic to a global audience, and it’s a fun one to discover. Valérian’s originality made it a fan favorite. It’s also surprisingly influential. In his 2007 introduction to the series, French critic and science fiction historian Stan Baretz wrote, “Catching it mid-run or discovering it today, in a world overflowing with heroic fantasy and virtual reality, Valérian might appear simple. Yet another spatio-temporal traveler juggling the mysteries of time and space? Wrong! In its time, Valérian was a groundbreaking series. It’s the original archetype from which everything flows.”

About that influence. The comparisons to Star Wars extend beyond the awkward depictions of aliens in The Phantom Menace. In fact, many of the film’s reviewers compared it to the Star Wars saga. Like Peter Debruge, who wrote in Vanity Fair, “Written as a kind of cocky intergalactic lothario, Valérian ought to be as sexy and charismatic as a young Han Solo.” (Spoiler alert: He isn’t.) There are plenty of other similarities between the comics and Star Wars: the all-aliens-on-deck festival-like aura of an intergalactic cantina, a hero encased in a clear yet solid slab, a heroine in a metal bikini, and a people who wear hightech helmets to cover their burned faces.

Mézières, the comic’s artist, also noticed the resemblance. Stan Baretz wrote, “It was in 1977 during the International Science Fiction Festival that had seen the cream of the profession gather in Metz, France. Included in the film program: the premiere of Star Wars in France. At the end of the film, I remember Mézières laughing and telling me: ‘It looked like an adaptation of Valérian for the big screen.’” One panel in Pilote #13 made Mézières’s feelings clear; it shows Valérian and Laureline on a double date with Han and Leia, sharing a table in a dim cantina, a hodgepodge of aliens gathered round. Leia says, “Fancy meeting you here!” Laureline retorts: “Oh, we’ve been hanging around here for a long time!”

His co-creator, series writer Christin, was more diplomatic. “That’s how it goes in sci-fi: it’s all about copying from one another,” said Christin in an English-translated interview with German newspaper Die Welt. “Or, in other terms, you borrow something from someone else and develop it further.”

Barets casts a fair bit of shade in his writings on the topic, but concludes with savoir faire, “All creators thrive on influences, of course. Things, as the saying goes, are in fashion, and Mézières has become philosophical about it. He knows, though, that he is one of the fathers of modern science fiction iconography, one of the main inspirations of that pool of images from which all later illustrators drank, consciously or not.”

Valérian’s core conceit is a pure genre classic: the time traveling space agent and his smart, sexy companion. (Doctor Who first premiered in 1963, so we probably can’t credit Valérian with the concept; it was simply the zeitgeist.) That’s the fantastic thing about speculative fiction—it’s a genre that begs, borrows, and occasionally steals, combining and recombining influences and still always managing to come up with something absolutely new. Some ideas are far too awesome to use only once.

FRANK ROMERO

Beyond D&D: Lesser-Known Fantasy Role-Playing Games

In 1974, a small self-publishing venture named Tactical Studies Rules (TSR) released Dungeons & Dragons. While D&D continues to be the first game that comes to mind when thinking of tabletop role-playing, the 1970s spawned a number of imitators, contenders, and pretenders to D&D’s popularity.

Tunnels & Trolls is the second role-playing game ever published. Self-published by a librarian named Ken St. Andre in April of 1975 and republished by Flying Buffalo later that year, T&T represents St. Andre’s fascination with fantasy role-playing and his reluctance to deal with the complexity he found in D&D. Tunnels & Trolls combat is decided by a roll-off between combatants. Perhaps the greatest innovation of Tunnels & Trolls is the amount of material supporting solo play, a revolutionary concept then and now.

That same year, TSR tried to replicate their success by publishing Empire of the Petal Throne by M.A.R. Barker, a Fulbright scholar and chair of South Asian Studies at the University of Minnesota. Barker went to Tolkienesque lengths to create the fantasy world of Tékumel, creating languages and writing thousands of pages of history. Empire of the Petal Throne provided a deep and complex setting hitherto unseen. Despite spawning five more games, five novels penned by Barker, and exerting influence on numerous other game designers, Empire of the Petal Throne remains undeservedly obscure.

Not all fantasy games involved wizardry and fighting men, however. In 1976, Fantasy Games Unlimited released Bunnies & Burrows, written by Dennis Sustare and Scott Robinson, and inspired by Richard Adams’s novel Watership Down. Players took the role of individual rabbits contending with warren politics, human encroachment, and basic survival. While the rabbits in the game didn’t swing swords or sling spells, they did use Bun-fu and participated in the first-ever skill-based system in a role-playing game. Bunnies & Burrows transcended the tropes that were rapidly becoming commonplace in the hobby and created a devoted fan base.

Perhaps the most notable non-D&D game published during the hobby’s infancy was RuneQuest, written by Steve Perrin and released by Chaosium in 1978. RuneQuest introduced a percentage-based combat and skill system. Set in the world of Glorantha, it allowed players to play as the same monsters they battled, including a race of intelligent ducks cursed by the gods. Despite not possessing the breadth of Tékumel, the fresh world that Glorantha provided paved the way for the complex worlds of the Forgotten Realms and the Dragonlance that D&D would come to use as its default settings.

An original illustration by Ashanti Fortson, inspired by the fanciful world of Bunnies & Burrows.

While none of these the above games became as popular as Dungeons & Dragons, they each catered to the needs of players that Dungeons & Dragons hadn’t yet served. The 1970s functioned as an incubator, sustaining an industry built on escaping the reality that grew out of the instability of the 1960s and early ’70s. Role-playing games allowed players to create a fantasy world where good triumphed with the strength of arms and the hidden knowledge contained in a spell book . . . simply by throwing some funny dice.

MOLLY TANZER

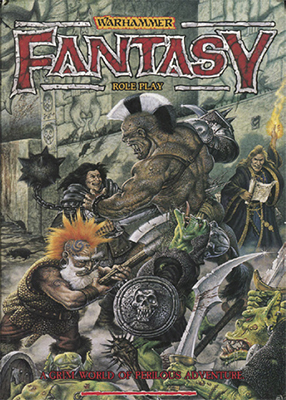

Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play:

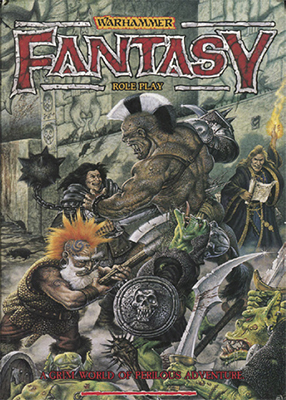

A Grim World of Perilous Adventure

These days, when gamers hear “Warhammer” they tend to think of miniature wargames, usually either Warhammer 40,000, a far-future science-fantasy setting where Dune meets Paradise Lost, or Warhammer Fantasy Battle, which puts your typical elves, dwarves, men, and halflings in a gritty setting called “the Old World” that has more in common with the Holy Roman Empire than Middle-earth. But in 1986, Games Workshop released Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, a pencil and paper RPG. Warhammer Fantasy Role Play is the grimdark cousin of Dungeons & Dragons and Pathfinder, taking its cues less from Tolkien and more from the Conan stories and Michael Moorcock’s Elric saga. After all, the first edition of WHFRP tells us right on the cover that the players are entering “a grim world of perilous adventure.” And it’s true, they are.

The perils of WHFRP aren’t just orcs, chimeras, and other fantasy beasts, however. Evil exists in the Old World, yes—but even at its worst, evil possesses motive. Evil can be understood, even if it is disgusting to the good (or those who are neutral).

Warhammer Fantasy Role Play First Edition Core Rulebook from Cubicle 7 Entertainment Ltd.

The forces of Chaos, on the other hand, are incomprehensible. Chaos has no ultimate goal—by its very nature that is impossible—but if it did, it would be to strip away the warp and the weft of civilization itself. Four gods are responsible for most of Chaos’s influence on the Old World: Tzeentch, the god of unending change; Nurgle, the god of plague and ruin, Khorne, the god of eternal war, and Slaanesh, the god/goddess of excess. Their agents are beastmen who prowl the wilds, sorcerers who traffic with demons, and sworn warriors who consider their mutations blessings. The kindly wizards of heroic fantasy have no place in WHFRP; to use magic is to risk being corrupted by Chaos, and thus your average citizen of the Old World is more eager to see a witch burn than to seek her out for a healing potion.

Indeed, man’s inhumanity to man is the real danger of WHFRP, a theme echoed by the system’s tendency to round dice rolls down, and always against the player’s interest. Starting players choose “careers” that fit into familiar classes such as warrior, academic, rogue, or ranger, and yes, one can roll a herdsman, a scribe, or a nobleman . . . but one can also come into the game as a political agitator, a bounty hunter, a grave robber, tax collector, or rat catcher. Some of the advanced careers include assassin, demagogue, highwayman, slaver, and of course, witch hunter. And in the end, even a witch hunter with full plate armor or a templar with a horse (most players start with a hand weapon, “sturdy clothes,” and maybe some pocket change) can—and will—be humbled by disease and madness.

The Old World is unforgiving. It’s best not to get attached to anyone or anything—but then again, if a player flees, their opponent gets a free attack with a +10 bonus. No parrying allowed, and shields provide no protection. For anyone used to the brighter, more merciful worlds of D&D and Pathfinder, WHFRP can be a nice change of pace, nice here meaning “delightfully frustrating.”

JESSE BULLINGTON

Kentaro Miura, Grandmaster of Grimdark

While the term “grimdark” may have initially been coined as a pejorative, it has undeniably become convenient shorthand for describing works of dark fantasy characterized by moral relativism, gritty realism, and graphic violence. George R. R. Martin was hardly the first author to take this approach to fantasy, but his A Song of Ice and Fire catapulted the subgenre into the mainstream consciousness and is widely acknowledged at the quintessence of the form—here in the West, that is. Years before the 1996 publication of Game of Thrones, Japan witnessed the rise of its own grimdark champion in the form of mangaka Kentaro Miura and his revolutionary Berserk.

A richly detailed world inspired by medieval Europe, rife with intrigue, betrayal, and brutal combat, where mercenaries and knights are pawns in the schemes of nobles . . . schemes soon eclipsed by a monstrous threat growing in the darkness. A cultural touchstone that has inspired countless imitators and been adapted many times over, to television, video games, and the big screen. A creator’s lifework that remains ongoing decades after its inception, provoking endless moans from entitled fans who resent the speed of the artist’s output and the sabbaticals between new installments.

Yes, we’re still talking about Miura.

Born in Chiba City in 1966, Miura began creating his own manga at a young age—his first comic appeared in a school publication when he was just ten years old, and by high school, drawing had become an obsession. While attending the Comi Manga School, Miura created a short comic about a hulking warrior taking on a shapeshifting Vlad Ţepeş (AKA Vlad the Impaler). This initial iteration of Berserk won a prize from his art school in 1988, and after working on a few other projects, he returned to his prototype.

The first official volume of Berserk was published in 1990. It introduced readers to Guts, a mysterious wanderer with a really big sword and an even bigger vendetta against the grotesque monsters that hide amongst humankind. While Miura’s art was impressive from the start, it wasn’t until the series flashed back to Guts’s past that the story transcended its roots to become something truly unique and phenomenal. This “Golden Age” arc, which is the heart of the Berserk saga, was first adapted as a twenty-five episode anime series in 1997 and then as a trilogy of animated feature films in 2012.

In “The Golden Age,” the overt supernatural elements of Berserk’s early chapters fade into the background as Miura chronicles the heroic rise and tragic fall of the Band of the Falcon, a mercenary company led by the ambitious Griffith. Against a backdrop of medieval action and courtly intrigue, Miura focuses the story on Guts’s complicated relationship with Griffith—and with Casca, the sole female captain in the Band. When the fantastical elements reassert themselves in the text it is to nightmarish consequence, and the grim fate of these three friends is the explosive conflict that has propelled Berserk for the last quarter century.

“Before Golden Age, I couldn’t decide if I want(ed) to make a pure fantasy story or a piece of historical fiction,” Miura told one interviewer. “. . . However, the moment when The Band of the Falcon took form in my mind, the name of Midland, a fictional country, emerged as well. The ‘historical fiction’ route stopped being an option, leading to Berserk turning into a fantasy story. And if so, I had to try using some trademark tropes of fantasy. Fairies, witch hunts, sorcery, pirate ships, et cetera. The representative features of medieval Europe.”

Miura is very open about the influences that contributed to his meticulously rendered anti-heroes, their world of gloomy forests and mist-wreathed cities, and the hideous monsters of every conceivable shape and size. He cites everything from earlier manga titles like Guin Saga, Violence Jack, and Fist of the North Star to Paul Verhoeven films and the Hellraiser series to the works of Hieronymus Bosch, M. C. Escher, Gustave Doré, and Pieter Bruegel. Miura even admits to picking up a few things from Disney films and credits an unlikely source for helping him crack open the emotional core of the series when he began the “Golden Age” arc: “As I like shōjo manga (romantic comics aimed at a teen girl demographic) as well, I thought I could change my methods and put in some sad human relationships and an emotional story. Until then, I was exclusively going down the Fist of the North Star route, but couldn’t compare with its author, Buronson-sensei. This is a good moment to try a different weapon . . .”

From this witch’s cauldron of inspiration, Miura continues to draw forth exciting new chapters as Berserk approaches its thirtieth anniversary. Having sold over forty million volumes around the world and with both a new video game adaptation and anime series released in 2016, Berserk continues to hold global audiences in its dark spell.

The Ambitions of BioForge

Released in 1995, BioForge is a vaguely cyberpunk action-adventure game that was literally ahead of its time. Developed by Origin Systems to run on DOS (remember DOS?), the game’s technical requirements were too extensive for most home computers. As a result, only the most dedicated of PC gamers with top-of-the-line hardware ever really got a chance to play it. Such are the risks of creation at the cutting edge!

BioForge official screenshot from Origin/EA digital catalog.

BioForge is set sometime, somewhere in the far future. Your character awakens to discover himself stranded in an alien facility on an abandoned moon. He has no memory of how he ended up here. Then it gets worse: He’s apparently undergone a series of body modifications and is now covered in cybernetic implants and metal prosthetics. As he eventually discovers, he was kidnapped by a religious cult called the Mondites, with a penchant for body mods—a story that almost feels like it could be written by Brian Evenson, perhaps our greatest contemporary writer of weird fiction. There’s also a hint of the thinking behind Doctor Who’s cybermen in the aliens’ quest to conquer the galaxy by remaking themselves as robots. Of course, the cybernetic implants also come with an advantage—as the somewhat indestructible marriage of man and machine, your character has better chances for survival and escape.

You wander around this facility, piecing together your past through documents found on terminals or within logbooks scattered throughout the complex. There are several levels to explore, and rooms that contain appropriately cyberpunk alien technology. You solve puzzles to unlock new areas of the facility, and fight enemies using guns, melee weapons, and sometimes your wits. Meanwhile, you’re on a search to figure out how you ended up here and what your captors are really up to . . . a foreboding sci-fi mystery with a touch of horror.

In 2013, Giant Bomb’s Patrick Klepek interviewed Ken Demarest, programmer, producer, and director of BioForge, and Demarest shared some recollections from the game’s development. “To some extent, it’s a reflection of who I was back then,” he said. “I cared about the technology, and that’s really all I cared about.” The technology was indeed cutting-edge—with running requirements that brought 1995 computers to their knees. But Demarest also fondly remembered his colleague Jack Herman’s “over-the-top crazy writing.” With that writing moved to journals and documents—not essential to the progression of the game, but simply there for players to enjoy at their leisure—Herman was free to explore the setting and backstory in whatever detail he pleased.

To be fair, beyond the fact that the game was so advanced technologically, the gameplay was decidedly clunky. The controls were awkward and the combat was slow and unwieldy, and sometimes unintentionally hilarious, as the characters continued to repeat the same dialogue over and over again while fighting.

Klepek believes that this clunkiness is in some way part of the game’s appeal: “The reason the game was so much fun to play, even now, is due to all the rough edges and the randomness and the weirdness. . . . It was clearly a labor of love, a game like this wouldn’t have existed without people who really wanted to make it.”

Origin Systems was known for their innovative work, and BioForge was part of this tradition. Originally, it started out as an “Interactive Movie”—which in those heady days of the early 1990s, was destined to be the next big thing. The form of the interactive movie was as yet pretty undetermined, so the studio wanted to take a stab at it and maybe even do some genre-defining work. As Demarest put it, “‘Go define what interactive movies can be, go do it.’”

Of course, interactive movies didn’t actually turn out to be a thing, and what the team ended up making is pretty clearly a video game. (“It may not be an ‘interactive movie,’ but there’s no doubt that BioForge is a compelling experience,” wrote PC Gamer in 1995.) But the idea of an “interactive movie” is obviously fundamental to the far more cinematic video games of today, the best of which combine solid plots, engaging dialogue, strong character development, and gorgeous visuals. Demarest believes that BioForge was one of the first games to do scripted cut scenes, as well as fully 3-D texture-mapped characters.

BioForge still has its loyal fans. A MobyGames user review from the early 2000s calls it “overlooked, underrated and unexplored.” Another terms it a “a highly underrated action adventure with a sci-fi feel to it.” Another calls it “a grand action adventure with one of the best plots, and best character-descriptions in the history of computer games.” In 2018, it’s more of a historical artifact than anything else . . . but still a fascinating and significant chapter in video game history.

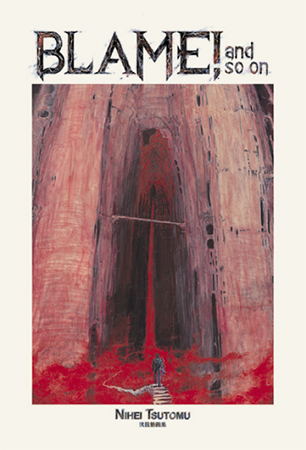

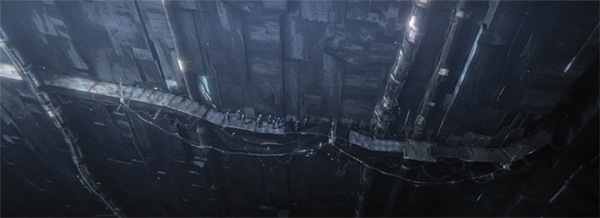

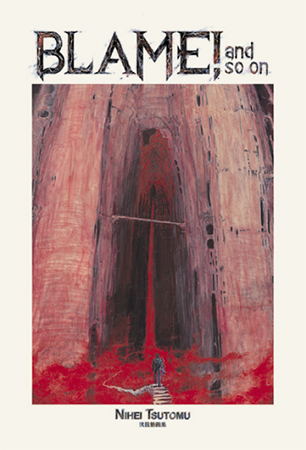

The Massive Artificial Landscape of Tsutomu Nihei’s Blame!

Though far from a household name in the United States, Japanese manga artist Tsutomu Nihei (b. 1971)—considered a mastern of modern sci-fi manga—has long maintained an enthusiastic cult following, wowing aficionados and collectors with the strength of his artwork, which manages to fit a sense of devastating vastness into each small panel. His vision of the far future is influenced by cyberpunk and biopunk, with a visual inventiveness that’s been invigorating and inspiring for creators beyond the bounds of manga and anime.

For instance, journalist Chris Priestman discussed Nihei’s influence on video game design, citing games from Aloft Studios such as NaissanceE, “an adventure taking place in a primitive mysterious structure.” Priestman writes, “What all these works have in common is that their creators have been inspired by Blame! and looked to transpose its design approach to a video game.”

Recently, the reach of Nihei’s work has grown significantly, since Netflix developed two of his manga series into anime features, both available to stream. Knights of Sidonia is a two-season show, with twenty-four episodes total. Blame! is a stand-alone film (106 minutes). The original graphic novels are also available in new, oversized editions from Vertical Comics.

Before he became a manga artist, Nihei was trained as an architect and also worked in construction. The influence is readily apparent in his work, which is filled with breathtaking depictions of futuristic built environments that begin to feel like characters in their own right. “Nihei’s art is simultaneously sparse and labyrinthine, his body of work defined by a unifying obsession with invented spaces,” wrote Toussaint Egan for Paste magazine.

Blame! premiered globally on Netflix in May 2017 (and also appeared in theaters in Japan). The film was directed by Hiroyuki Seshita, with story and writing by Tsutomu Nihei. A sequel is underway.

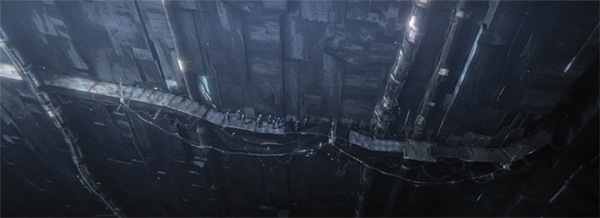

The effect is one of awe, alienation, and utter loneliness; humans both dominated by and disconnected from this massive artificial landscape their ancestors built long ago. Thematically, it’s akin to Jack Vance’s Dying Earth books—a civilization overshadowed by the weight of its history, a world in decay. Aesthetically, it’s biopunk and cyberpunk, with cyborgs, aliens, and genetic engineering. This unique combination has been massively influential on the genre as a whole, its inspiration spilling over into fiction, film, and game design.

Nihei’s first big work, Blame!, is set in a far-future megastructure the size of the world, or possibly even larger—its inhabitants are unable to measure or even estimate its total size. This self-replicating megastructure is simply called The City. It’s a smart city, and in its own uncanny cyborg way, it is alive, and hostile. Once humans had the ability to control the machines with their minds, and thus the city. They lost that ability, and now they’re refugees in the world they built, hiding out from the Safeguard, killer robots whose only job is to eliminate them. A mysterious young man named Kyrii (also spelled Killy) traverses this landscape, empowered by a lethal device (aka a gun) called the Graviton Beam Emitter, in search of a human who still possesses the “Net Terminal Genes”—which could allow humanity to take control of their world once more. But as with every quest story, the narrative is less about the destination and more about the journey, using Kyrii’s perspective to explore the world.

As Jason Thompson wrote in Manga: The Complete Guide, “The amazing thing about Blame! is that it’s such a good read even though it has almost no story or characters. It’s all about the art and the experience of being there, of not knowing what will happen next, of the contrast between landscapes of endless sameness and bloody eruptions of chaos and gore.”

The anime feature capitalizes on this by honing in on one story and one adventure among many (leaving the option open for a sequel or even a series). The movie centers on a handful of kids in an isolated, struggling village that’s running out of food and on the brink of starvation. We see the story from their perspective, as the mysterious stranger named Kyrii arrives in town (after rescuing them from the Safeguards) and, while continuing to pursue his own search for the net terminal genes, also helps the village carve out a new means for survival. While the story may be small-scale, the world it depicts is just as massive as it is on the page, and the film’s biggest strength is its wide panning shots of tiny humans miniaturized by the awe-inspiring scale of their empty and desolate surroundings.

Kyrii is a hero of few words, a mostly silent and enigmatic figure—especially to the curious and grateful villagers. Their first introduction to him is via his Gravitational Beam Emitter, a rare, powerful weapon capable of blasting massive holes in the landscape.

Knights of Sidonia is set in a similarly artificial environment, but this one is a spaceship, traversing the desolate wilderness of empty space a millennium after the solar system has been destroyed. “Nagate Tanikaze has only known life in the vessel’s bowels deep below the sparkling strata where humans have achieved photosynthesis and new genders,” reads the cover copy from Kodansha Comics. Much like in Blame!, humanity is menaced by a hostile and alien life form—this time actual aliens—whose sentience and perspective is so foreign to our own that negotiation is impossible.

Nihei’s third major work, Biomega, is also set on earth, in another brutal and decaying artificial landscape, which is in the process of succumbing to a zombie plague. Its synthetic android protagonist, immune to the zombie virus, traverses this apocalyptic world on a motorcycle in search of humans who are also immune.

With its preoccupation on the distant future, the built environment, and the augmented human in an artificial world, Nihei’s work tackles the biggest questions of science fiction: What human thread connects us to the future, and what remains when everything is changed? But it’s not all philosophical. With intensely choreographed fight scenes and breathtakingly gorgeous visuals, there’s plenty of eye candy there, too.

ROBERT LEVY

Raëlism:

The Space-Age Message of the Elohim

A great many of us earthlings—and presumably a decent percentage of this book’s readership—have a fascination with the potential for extraterrestrial life. But who among us can claim that the existence of aliens forms the core of our religious views? Enter the Raëlians, the real-life believers in a theological doctrine centered on the premise that life on Earth is a result of alien experimentation, and that these technologically advanced beings walk among us still. They are called the Elohim.

The faith was established in 1974 by a French journalist and racecar test driver named Claude Vorilhon. During an initial close encounter with a kindly ET named Yahweh at the Puy de Lassolas volcano park, the alien shared with him the first of many messages to impart to humankind. Vorilhon was subsequently brought to a distant planet, where he learned that he himself was half-Elohim, as well as the Last Prophet to humanity that would herald the extraterrestrials’ final return. Renamed Raël and introduced to other fellow ambassadors such as Moses, Buddha, Jesus, and Mohammed, Vorilhon became determined to spread the Elohim’s message, as well as prepare us for the reemergence of our alien designers.

Thus a religion (though some would say cult) was born, one that has swelled to many thousands of followers across the globe (just how many thousands is a source of dispute). There is no sacred text in Raëlism, though Raël is himself an author of many books, including The Message Given to Me by Extra-Terrestrials, Space Aliens Took Me to Their Planet, Sensual Meditation, and Yes to Human Cloning. Oh, and their symbol is a swastika integrated into a Star of David, a conflation later obscured when the logo was redesigned during the church’s effort to build an embassy for the Elohim in Jerusalem (the attempt was ultimately rebuffed by the Israeli government).

Raëlism is known for its disavowal of theism as well as its many pro-science and sex-positive stances and initiatives, which can be traced back to the movement’s principal tenet that human life is shaped in the alien Elohim’s own image. Take Clonaid, for example, a project launched by Vorilhon and Raëlian bishop and chemist Dr. Brigitte Boisselier in order to advance cloning, and in 2001 Dr. Boisselier and Clonaid claimed to have secretly cloned the first human being. Another noteworthy endeavor is Clitoraid, a clitoral reconstruction mission started in 2006 that seeks to open a “pleasure hospital” in Burkina Faso to combat female genital mutilation. And then there’s Go Topless Day, an annual (and self-explanatory) celebration in August timed to coincide with Women’s Equality Day.

Blurring the boundaries between human and alien, pseudoscience and science fiction, self-promotion and legitimate activism, Raëlism might not be the largest or most famous UFO religion—it’s certainly not the one with the most celebrity devotees—but it just might be the most forward-thinking. As for the future of the Raëlian movement, it depends on how enthusiastically we embrace the return of our extraterrestrial creators. Let’s try not to disappoint them, shall we?

CyberCity: Hackers, Virtual Reality, and the Games Of War

So you know how the shockingly plausible scenario of WarGames aroused the concern of President Ronald Reagan (see this page), and led to the United States’ first major cybersecurity initiative? Science fiction has always been majorly intertwined with the more forward-thinking elements of the U.S. military, and vice versa.

Today, the military is using virtual reality worlds to anticipate and prevent potential cyberattacks that seem like something cyberpunk writers like William Gibson or Neal Stephenson might have once dreamed up. With recent reports of Russian state hackers penetrating U.S. utilities like electrical grids, these fears are becomingly shockingly real.

One expert at the forefront of the video game/cybersecurity nexus is Ed Skoudis, owner of the company Counter Hack, and a highly sought-after instructor on cyber incident response. Skoudis’s first claim to fame was a video game called NetWars, where the player’s goal is to stop cyberattackers from . . . well, cyberattacking. Both corporate computer security experts and military defense personnel used NetWars as a training tool. But they also wanted something more; they wanted something that felt less like a video game and more like real life.

Skoudis recounts the conversation to Eric Molinsky on the Imaginary Worlds podcast. He’d been presenting NetWars on a military base when a commander told him, “What we need is something that teaches our warriors that cyber action can have kinetic effect”—i.e., that stuff cyberattackers do doesn’t just affect our digital lives. Malicious hackers can impact our physical surroundings by targeting traffic signals, water treatment plants, hospital systems, the power grid. Skoudi took the commander’s words to heart and began brainstorming a more tangible approach. The result is CyberCity, a “fully authentic urban cyber warfare simulator” built with the support of the U.S. Air Force.

CyberCity is a digital world, but it’s a model of a real city, too. The model town, deep in Skoudis’s lab (in an undisclosed location on a secret military base), is just 6′ × 8′, but it has all the amenities of a real town of 15,000 people—a bank, a coffee shop (with unsecured WiFi), an elementary school, a power grid, a water treatment plant, a hospital, public transit, business offices and residential cul-de-sacs, and even a local newspaper.

A sunny day in CyberCity. Photo taken by radio producer Eric Molinsky, host of the Imaginary Worlds podcast.

While the model town might look like the kind of project a particularly obsessive hobbyist might build in his garage, it’s connected to an advanced virtual reality. Molinsky says, “The city itself is built pretty cheaply—they just went to a hobby shop. But the power grids that run this model, that run the lights and the little train that goes around this town, they had to be tiny duplicates of the kind of equipment that Amtrak or Con Edison use.” That power grid is hyperrealistic, designed by a real engineer who also designs power grids for military bases. And the residents of CyberCity have digital lives too, with email and bank accounts, and even a social networking site called FaceSpace.

So how do U.S. defense forces use this as training tool?

The assignments vary from day to day. Skoudis’s team plays the role of cyberterrorists. They hack into the networks that power CyberCity, contaminating the water at the reservoir, targeting the natural gas pipeline, shutting off the lights, or derailing the local train. The cyber-defense trainees must figure out how to use cyber-warfare tools to stop them. They are training from all over the world—but as they solve the puzzles, they remain hooked into a live visual feed of CyberCity, a reminder that virtual actions have physical consequences. When real-life cyberattacks happen, there are lives at stake.

The charming verisimilitude of CyberCity is part of that psychology. On Imaginary Worlds, Skoudis offers a little tour of CyberCity’s homey qualities: “There’s fire hydrants, there are mailboxes. Now let’s go over to the houses, over in the residential quadrant. There’s a dog, there’s a rug that’s airing out, there’s a rocking chair on the porch. I told you, it feels kind of like home.”

There are also some fun nods to CyberCity’s science fiction roots. For example, the DeLorean parked along a quiet street. In one mission, zombies invade the city. After the cyber-defenders prevail, they’re supposed to hack into the billboards to let the CyberCity populace know the zombies are defeated and it’s safe to emerge. (Don’t panic—this was not a specific request of the U.S. military. Skoudis’s team designed the zombie outbreak mission solely for their own amusement.)

But despite the quirky details, CyberCity is deadly serious.

“CyberCity provides insight into some of the Pentagon’s closely guarded plans for cyber war,” writes investigative reporter Robert O’Harrow Jr. for the Washington Post. “It also reflects the government’s growing fears about the vulnerabilities of the computers that run the nation’s critical infrastructure.”

“It might look like a toy or a game,” said Skoudis. “But cyberwarriors will learn from it.”

K. M. SZPARA

On the Internet, No One Knows You Aren’t a (Gay) Wizard:

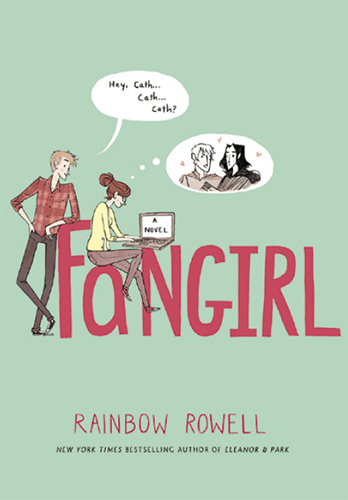

An Ode to Fan Fiction

Like many nineties kids, I grew up with Harry Potter. Literally. We were both eleven in 1997. We both wanted to be wizards. We both faced adventures during school—though mine involved fewer dragons. He had spats with teachers and friends, and experienced all the angst of growing up as a pubescent teenager. He was everything I wanted except for one thing. He wasn’t gay.

I didn’t know I was gay then, because I didn’t even know I was a guy then. I was a teenage girl reading Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix by lamplight while Harry watched Draco Malfoy’s every move on the Marauders’ Map, by wandlight. But while an abundance of magic stopped technology from working at Hogwarts, in the muggle world, the Internet was taking off. On the Internet, Harry Potter could be gay. And so could I.

I’m not the only queer writer with this origin story—nor is Harry Potter the only fandom through which baby queers experienced personal revelations—but those stories go something like this: Many of today’s twenty- to thirtysomething authors grew up during a time when Young Adult was beginning to take shape as a defined category and become part of the larger popular culture conversation, and during which the Internet provided a way for people to discuss their interests. Though fanfic has existed for much longer, through zines and other creative works, our generation experienced it with unprecedented speed and convenience.

Those of us with Internet access could spend hours online, often during which our parents had no clue what we were doing. I was privileged to attend a high school that instituted a laptop program, and, in the early 2000s, Internet safety extended to “don’t use your real name online.” So, while I was waiting for J. K. Rowling to finish writing the next Harry Potter book, I filled the void with wizarding worlds where Harry Potter and Draco Malfoy ventured from enemies to lovers. Where a magical war chewed them up and spit them out, jaded, angry, and mottled with scars. Where they were the only ones who could understand each other. Where they were G-A-Y.

Fanfic became an underground space where readers could bring themselves to light. So many characters were—and still are—cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied, neurotypical, and white. Plenty of readers are all of those things, but many are not. I, for example, identify as a femme gay trans guy. I am also white, able-bodied, and neurotypical, but failed to find many characters like me growing up.

The only book in which I did was Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles series. It blew my mind that her vampires were queer on the page—so many dog-eared scenes in my paper-backs—and yet it failed to make the impact Harry Potter did, despite Harry being straight and cisgender, because Anne Rice doesn’t allow people to write fanfic. Technically, it utilizes copyrighted material. An author could issue takedown notices to fanfic authors, but most choose to ignore it, assuming no money is being made from their intellectual property.

Rice’s fans are forced to exchange fanfic through private means, write for themselves or not at all. So while the characters are canonically queer, there’s no means for fans to imagine themselves as queer vampires. To interrogate the world through her stories or reimagine her characters. To suggest that dandy Lestat de Lioncourt might experiment with his gender identity.

When fans are allowed to experiment without constraints, however, magic happens. Take, for example, author thingswithwings’ Captain America fanfic “Known Associates.” Published in 2016, “Known Associates” is an approximately 300,000-word story about a queer Steve Rogers who identifies as a fairy and experiences bodily dysphoria once he becomes Captain America. Queer and trans people rarely see their experiences reflected authentically in mainstream fiction, which is why so many turn to fanfic. Thingswithwings utilized what Marvel didn’t—and maybe couldn’t: that while a souped-up muscle-body might be a fantasy for straight cis men, it could trigger gender dysphoria for a genderqueer person.

It’s important to note that in 2018, “Known Associates,” in all its queer glory, broke a barrier between original fiction and fan fiction when it was selected for the Tiptree Long List, which recognizes writing that “encourag[es] the exploration and expansion of gender.” However, it’s not the first penetration of fandom into mainstream fiction. Cassandra Claire is famous for having written The Draco Trilogy, which helped shape the fandom characterization of Draco Malfoy, whose arc in the Harry Potter series left many readers unsatisfied. Claire, a BNF (“big name fan”), went on to write The Mortal Instruments, a YA urban fantasy series, as Cassandra Clare. Though she deleted her fanfic from the Internet, Clare set a precedent for writers moving between fan and original fiction.

In 2013, Rainbow Rowell published Fangirl, a contemporary YA novel about a college freshman who is a BNF in a fandom similar to Harry Potter. Furthermore, in 2015, Rowell published Carry On, the novel-length fanfic the protagonist of Fangirl is working on, wherein Simon Snow, teen wizard and Chosen One, fights an evil magical force, while falling in love with Tyrannus “Baz” Basilton Grimm-Pitch, another teen wizard who is also a secret vampire and secret queer.

While Fangirl is mainstream validation of how fanfic not only transforms original works, but also how readers and writers interact with their personal identities and the world at large, Carry On provides direct commentary on aspects of Harry Potter that Rowling didn’t dig as deeply into, such as the abuse Harry suffers at the hands of his caregivers and Dumbledore, as well as what it means to be a Chosen One. But beyond thematic exploration, Rowell queered the Harry and Draco analogue characters, as well as gender- and race-bent several secondary characters.

Fiction, both fan and original, has always provided me a space to explore what it means to be a queer and trans person, through my protagonists’ stories. I was myself in fiction before I was myself in real life. And now I’m a grown-up writer, like so many of my peers. While I was getting to know the science-fiction and fantasy community of writers and publishing professionals, I hid my origin story. I was ashamed that I hadn’t read all the straight cisgender white authors that were named on convention panels and in essays as the Science Fiction and Fantasy Canon. My canon was comprised of queer fanfic. I’m not ashamed anymore.

The Internet fan fiction generation is done with fanfic being treated like unoriginal, derivative work that’s cast off as porn. It is worthwhile for many personal reasons, but also because it’s taught a generation of emerging authors to experiment with stories. To write without worrying whether their plots are too tropey, their sex too gratuitous, their queers too unpalatable for the masses. To experience unabashed enthusiasm for characters. To bring all that to their original fiction and science fiction and fantasy at large.

SYLAS K. BARRETT

The Time of the Mellon Chronicles

The Return of the King stars Orlando Bloom (left) as Legolas Greenleaf and Viggo Mortensen (right) as Aragorn. Despite his boyish charm, the immortal Legolas is actually ancient; his 87-year-old friend Aragorn is youthful in comparison. Photo credit: Moviestore Collection / Shutterstock.

The fandom mailing list is likely as old as fandom itself. Letters and zines have always allowed fans around the world to build communities that shared the same passions. Once, physical mail was the only way large groups of fans could communicate with each other across such distances; but just as the Internet has greatly reduced the popularity of paper letters, it has also changed the way fans interact. Now, they share their thoughts on Twitter and Reddit, post drawings and photo manipulations on Tumblr or DeviantArt, and store their fan fiction on Websites like Archive Of Our Own.

And yet there was a moment, a brief springtime of the Internet, in which people tried to use the web the way it had once used the postal service. This was the time of Yahoo mailing lists.

This was the time of The Mellon Chronicles.