Though wildly influential, the 1927 film Metropolis has existed in a fragmented and incomplete form for most of its history.

Though wildly influential, the 1927 film Metropolis has existed in a fragmented and incomplete form for most of its history.

In many ways, film and television are as foundational to science fiction and fantasy as is the more ancient art of literature. Through visual spectacle, inventive set design, and special effects, moving pictures spark the imagination in their own unique way.

This chapter explores some of the earliest entries in the one hundred-plus year-old tradition of SFF cinema; the work of ambitious filmmakers who through their nascent visions of a genre not yet defined, laid the groundwork for the field that would eventually bring us Star Wars, Star Trek, and Doctor Who.

We also imagine a few of the films that could have been—from Jodorowsky’s Dune to William Gibson’s Alien III, from an erotic “film noir” take on aliens in Manhattan to a horror-movie precursor to E.T. While they never made it to the big screen, these visions live on in screenplays, concept art, storyboards, and more; and their raw inventiveness influenced Hollywood and spawned many imitators.

Finally, we pay tribute to the unsung all-stars of moving pictures—concept artists. Though they seldom get the red carpet treatment reserved for directors, producers, and actors, concept artists have played a particularly essential role in SFF cinema, inventing the memorable and arresting characters and creatures, landscapes and planets, futures and pasts that make science-fiction storytelling so delightful.

Bonus: The science fiction movie that shaped American military policy; why Star Wars got slapped with a lawsuit for ripping off a Buck Rogers serial from the 1940s; the scientific discoveries of James Cameron; and a couple not-quite-canon films that shaped the genre.

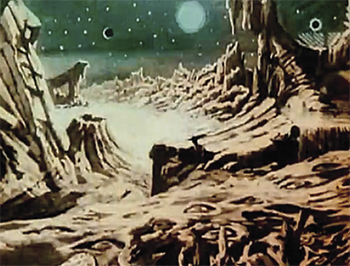

Science fiction’s first film is a surreal twelve-minute extravaganza created by a magician turned filmmaker. Le Voyage Dans la Lune (or A Trip to the Moon) was made in 1902 by French filmmaker Georges Méliès (1861–1938). No doubt fueled by his practice of the magical arts, Méliès brought an incredible sense of the surreal and fantastic to his visual storytelling. The short film’s most recognizable image—a makeshift space capsule landing in the eye of the Moon—remains one of the most iconic visuals in cinema history. The same image is often referenced in art and graphic design, particularly to evoke the retrofuturistic aesthetic of steampunk, H. G. Wells, and Jules Verne.

Indeed, Verne and Wells were both influential to the filmmaker and the film, Verne with From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon (Méliès called these major influences) and H. G. Wells with The First Men in the Moon, which was published in French just a few months before Méliès made Le Voyage Dans la Lune. He was quite likely also influenced by an operetta by Jacques Offenbach, also titled Le Voyage Dans la Lune, which parodied the works of Jules Verne.

Méliès starred in the film as Professor Barnenfouillis, leader of the voyage. The story follows the professor and his colleagues, a group of six astronomers (fancifully named Nostradamus, Alcofrisbas, Omega, Micromegas, and Parafaragaramus) who build a cannon-propelled, bullet-shaped space capsule, along with an appropriately sized cannon to launch it to the Moon. The six astronomers are loaded in and fired off by young women playing the role of flight attendants, dressed in sailors’ outfits. The Moon watches benevolently as the capsule courses toward it, sinking into its eye, in the image that’s become so iconic.

Built in 1897, Méliès’s film studio in Montreuil, Seine-Saint-Denis was modeled after a greenhouse, inviting plenty of sunlight through the glass walls and ceiling to aid in filming.

There are plenty of other striking and beautiful visuals in the film, which is done in a highly theatrical, stage-play influenced style (as film, in its early days, still sought its own voice). Each shot is packed full of action and visuals, with many actors in each scene, moving both individually and together in a complex choreography that occasionally becomes chaotic. The imagery is surreal and baroque, and the storytelling is racuous and slightly comedic, tongue in cheek.

The astronomers disembark from their capsule and bed down on the surface of the Moon. They watch Earth rise as they fall asleep; mythological celestial bodies frolic overhead. It begins to snow. They run to hide in a cave filled with giant semi-sentient mushrooms. There, the astronomers encounter a lunar inhabitant called a Selenite, who they promptly kill—pretty effortlessly, as the Selenites explode when struck. But many more Selenites soon appear, and the astronomers are captured and taken to the court of the Selenite king. One of the astronomers body-slams the Selenite King, who disintegrates into a puff of colored dust.

The Selenites pursue the astronomers as they run back to their capsule in a hasty attempt to escape. With no cannon to launch them back to Earth, Professor Barbenfouillis ties a rope to the space capsule to tip it off a Moon cliff and into the void of space. An attacking Selenite stows away at the last moment and makes it back to Earth with them. The capsule lands in a sea and is towed to shore. The Selenite ends up a captive in their celebratory parade.

The story sounds simple, but this film was one of the earliest narrative movies ever made. In that sense, its twelve-minute story was a groundbreaking achievement for film. Technically, it was also impressive, drawing on a larger budget than usual, a longer filming schedule (three months), and an unusually lavish and detailed film set. The film studio Méliès worked in had a large glass roof, which appears in the film as the astronomers build their spacecraft. The film’s special effects drew particularly on substitution splices—the cameras would stop rolling for a second, they’d switch up some stuff in the shot, and then splice the two shots together to create the visual illusion. That’s how Méliès achieved the shocking and delightful shot of the astronomer’s umbrella suddenly transforming into a giant mushroom. The iconic sequence of the capsule in the eye of the Moon was also created using this early special effects technique. Here, Méliès’s background as a magician no doubt came in handy, as he was already accomplished in the art of redirecting the eye to create the illusion of magic.

The original film is silent, though when shown to contemporaneous audiences, it was usually accompanied by a narrator as well as live music and other sound effects. In the century since, many composers have tried their hands at creating music for it. The French band Air (see this page) created a composition for it that offers a great accompaniment to the 2011 color-restored version.

Méliès made hundreds of short films over his career, leaving an indelible mark on the history and art of the cinema. Wildly popular at the time of its release, Le Voyage Dans la Lune remains his best known work today. The film can be seen in its entirety online, and at just twelve minutes, it’s a worthwhile and enjoyable watch for anyone who is interested in the history of SFF cinema!

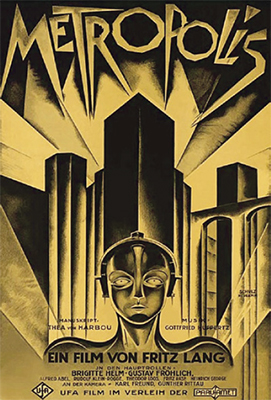

Film historian David Bordwell calls Metropolis (1927) “one of the great sacred monsters of the cinema.” As one of the seminal texts of science fiction, Fritz Lang’s famous silent film is both holy and profane. Visually, it’s a groundbreaking work whose production set standards in the still-youthful medium of film, and whose arresting aesthetic has been one of the most influential in shaping our conception of the future. Narratively, its story has been almost wholly incoherent for most of its ninety-year history, thanks to a botched editing job and lost footage. Politically, the film’s story can never be fully disentangled from its disturbing connections to the Third Reich.

Metropolis premiered in Berlin in 1927, a collaboration between Fritz Lang (1890–1976) and his wife, Thea von Harbou (1888–1954). The screenplay was written by von Harbou, developed in tandem with a novel by the same name. Lang and von Harbou had been co-writing all of Lang’s movies since the beginning of their partnership in 1921, and the collaboration had already proved creatively fruitful with popular hits, including a five-hour retelling of the folklore epic Die Nibelungen (taking place over two films). Adolf Hitler called the film his favorite, a more damning recommendation than it probably deserves.

But Metropolis was Lang and von Harbou’s most ambitious collaboration yet. It was a big, expensive production—the most expensive in Germany at the time—encompassing hundreds of extras, extensive set design, and pioneering special effects. Metropolis, for all its expense, was also a commercial flop. Its failure was the final straw for the already struggling film studio UFA, which declared bankruptcy. UFA was then purchased by Alfred Hugenberg, a powerful German nationalist and eventual Hitler supporter. As the Nazis came to power, UFA films became vehicles for Nazi propaganda. More on that later—but first, back to the film.

Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou at work together in their Berlin apartment. This picture was taken in 1923 or 1924 for Die Dame magazine.

Metropolis’s story centers on a futuristic city that’s a frenzy of inequity; the capitalists frolic on the surface in opulence and luxury while the workers labor in a subterranean factory, serving a machine. The ruler’s son Freder discovers the bleak slums below his pleasure gardens and is horrified; he volunteers for a stint with the machine, the better to relate to the common people. He falls in love with Maria, a saintly woman from below, who serves as the people’s prophet, preaching patience and submission. Meanwhile Freder’s father, the ruler of Metropolis, conspires with an evil scientist named Rotwang to replace Maria with a look-alike robot (presaging replicants, Cylons, and synths). According to her programming, robot Maria spurs the proles toward revolt—and chaos ensues. If this seems confusing to you, you’re not alone.

In a contemporaneous review, H. G. Wells called it “unimaginative, incoherent, sentimentalizing, and make-believe.” These were far from his only unkind words for the film, which he also termed “immensely and strangely dull,” “ignorant, old-fashioned balderdash,” a “soupy whirlpool,” “with a sort of malignant stupidity.” It was a long review.

Never especially airtight to begin with, the film’s plot was rendered even more incoherent by aggressive editing within months of its release. The Berlin original premiered at 153 minutes. The version U.S. audiences saw was only 115 minutes—with a whole new script created by American distributors for American audiences. In 1936, an even shorter ninety-one-minute version was released. Then Fritz Lang’s original cut was lost—and with it, a full hour of footage.

For eighty years, Metropolis fans lamented the loss; for a time, almost no one alive had even seen the original cut, only the badly mutilated version often played at silent film festivals. As journalist Larry Rohter wrote in the New York Times, “For fans and scholars of the silent-film era, the search for a copy of the original version of Fritz Lang’s ‘Metropolis’ has become a sort of holy grail.”

The story of how the missing footage was eventually located is a fascinating piece of history in and of itself. It was discovered by Fernando Peña, an Argentine film archivist, in the archives of Buenos Aires’s Museo del Cine. He did not stumble upon it by accident; in fact, he’d heard rumors of its existence for twenty years, but his attempts to unearth it were ever thwarted by bureaucracy. In 2008, when his ex-wife and fellow film archivist Paula Félix-Didier became director of the Museo del Cine, she invited him over to have a look. They got to searching and discovered the full-length cut. Some of it was damaged beyond repair, but plenty was salvageable, adding another twenty-six minutes to the film. (How did a German film end up in an Argentinian archive? Sheer coincidence. It was purchased soon after the premiere by Argentine film distributor Adolfo Wilson, who just happened to be visiting Berlin. He brought the 35mm reels back home with him. Eventually it became part of a private collection and then a government archive.)

The newly discovered material helps clarify the story considerably, making it a little easier to offer a plot summary. But the power of Metropolis has never been its story; it’s always been the visuals. In a review for Tor.com, science fiction author Kage Baker wrote, “Yes, the visuals are brilliant . . . It’s a seminal film. Certain images are unforgettable. You should certainly watch it if you get the chance. It still stinks.” Kinder words than H. G. Wells might have used, certainly, but her conclusions were much the same: as a work of science fiction, it is extremely bad.

As an aesthetic, though? Metropolis really is stunning, in its rendering of a city somehow both decadent and drab, a double-edged future both luxurious and nightmarish. “Even if you’ve never seen Metropolis, you’ve seen a film, a dress, a building, or a pop video that was inspired by it,” wrote journalist and film critic Pamela Hutchinson in the Guardian. “The film’s look—the teetering architecture, the lever-and-dial mechanisms, the round-shouldered workers marching in unison, and of course, the robot . . . This silent film fires the imagination of everyone who sees it.”

The gold robot that graces the Metropolis poster might seem especially familiar. Legendary Star Wars artist and concept designer Ralph McQuarrie later based his vision of C-3PO on Metropolis’s robot, before she’s transformed into the Maria look-alike. (See this page for more on McQuarrie.) And the story itself, in which a ruler father and a socially conscious son butt heads, might also have served as a Star Wars influence.

Roger Ebert also noted the film’s vast influence on the genre, listing many other science fiction classics: Dark City, Blade Runner, The Fifth Element, Alphaville, Escape from L.A., Gattaca, and even Batman’s Gotham City. Ebert also mentioned that “the laboratory of its evil genius, Rotwang, created the visual look of mad scientists for decades to come, especially after it was so closely mirrored in Bride of Frankenstein.” Those decades continue; in its artfully self-aware depiction of Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory, the recent television show Penny Dreadful (2014–2016) casts its mad scientist in surroundings that bear a striking similarity to Rotwang’s, and remain as recognizable to us as ever.

Though the film was a commercial failure in Germany, it did find some unwelcome supporters: Hitler and his minister of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels. In 1933, Goebbels invited Lang to his office and offered him a position as head producer of Nazi propaganda films for the now state-controlled UFA. According to Lang’s account, Goebbels told him, “The Führer and I have seen your films, and the Führer made clear that ‘this is the man who will give us the national socialist film.’” In Lang’s telling, he immediately went home, packed his bags, and fled to Paris, leaving with such haste that he was unable to even stop at the bank. The story is probably apocryphal—a bit of self-mythologizing on Lang’s part—as the evidence suggests he left Berlin within a few months, not a few hours. He also divorced von Harbou.

While Lang chose to leave Germany, von Harbou did not. Instead, she joined the Nazis and worked on propaganda films. The extent of von Harbou’s own commitment to Nazi ideology remains an open question, although not a particularly relevant one. Whatever her personal beliefs, her role in the party’s PR wing is simply indefensible. Perhaps von Harbou’s Nazi affiliation is why her contributions to Lang’s films from that period have been minimized. Perhaps, in the tradition of co-creator husbands and wives, they would have been minimized regardless; it’s hard to say. Surfacing the contributions of unsung creators can also unearth some secret histories we’d prefer to forget.

Long before George Lucas forever revolutionized science-fiction cinema with Star Wars, he wrote and directed a slow-burning, visually arresting film titled THX 1138. Though certainly not as commercially successful as Lucas’s later endeavors, THX 1138 is a dystopian classic, massively influential on the genre. In fact, it’s one of those works that actually suffers from its own impact; you’ve probably already seen a dozen later films that drew on this one as inspiration, making the original feel oddly derivative. (To be fair, the plot is pretty derivative itself, drawing on classics of mid-century dystopian literature such as George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. But the film’s coldly oppressive atmosphere and stunningly bleak visuals have influenced many later visions of a high-tech dystopia.)

George Lucas paid tribute to his debut film with numerous references hidden in the Star Wars saga, particularly the number “1138,” which is linked to cell blocks, battle droids, and more.

THX 1138 began as a student film for George Lucas. He later reshot it as a feature film under the mentorship of Francis Ford Coppola, who had pitched it to Warner Bros.—with a tiny though bizarrely specific budget of $777,777.77. (Perhaps you can guess at Coppola’s lucky number.) Meanwhile, Lucas was paid only $15,000 to write and direct the film. Not much, but also not bad for a twenty-three-year-old.

The film is set in a repressive underground society where technology reigns supreme, sex has been eliminated, and the drug-sedated populace labors emotionlessly to increase production. Constant surveillance and impassive robot-policemen enforce the law. The titular character, THX 1138 (played by Robert Duvall), falls in love with his female roommate. They stop taking their drugs and begin a sexual relationship, falling afoul of the law. Though not without its share of action sequences, the film suggests that freedom from oppression must first be found in the mind.

“THX was perceived as a bleak, depressing film upon its release,” writes film professor and producer Dale Pollock in Skywalking: The Life and Films of George Lucas. “Even its admirers consider the movie to be austere and unemotional.”

Honestly, it’s difficult to imagine how this film could have come from the same director as an action-filled, big-hearted adventure like the Star Wars saga. Pollock suggests that audience reactions to THX 1138 may have altered Lucas’s perspective. “Lucas learned from the critical and popular reaction to THX that if he wanted to change the world, showing how stupid and awful society could be was not the way to proceed. It was a mistake he wouldn’t repeat.”

Instead, Lucas decided to make feel-good films with an aspirational vision. In Star Wars, rebels still risk everything to fight oppression—but good can triumph over evil. And unlike the bleak vision of THX 1138, which offers no alternate way of living for its characters, the Star Wars rebels are very clear on the world they want to build: a kinder galaxy where diversity is celebrated, life is cherished, and all planets deserve a right to self-determination. In the (much later) words of one Rose Tico: “Not fighting what we hate, but saving what we love.”*

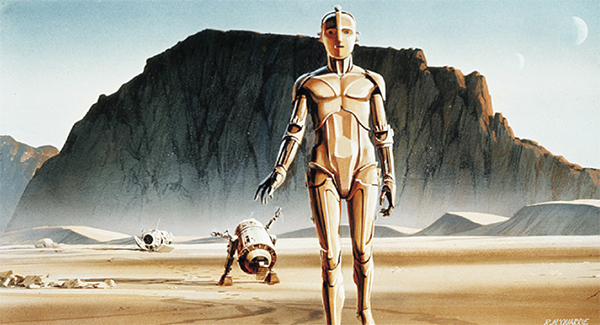

You don’t often hear his name spoken with the same reverence as George Lucas, but in his own way, Ralph McQuarrie (1929–2012) was equally instrumental in the making of Star Wars. The concept artist was the first person Lucas recruited to his design team—and his exacting, vibrant illustrations were crucial to obtaining funding for the film. With the paintings on hand, 20th Century Fox executives could really picture what Lucas was going for with Star Wars—and how groundbreaking it would be. McQuarrie continued to hold this pivotal role as visual designer of the Star Wars universe. In a tribute to McQuarrie’s contributions—and their role in motivating and inspiring the whole Star Wars cast and crew—Lucas said, “When words could not convey my ideas, I could always point to one of Ralph’s fabulous illustrations and say ‘Do it like this.’”

Doug Chiang, who served as design director on Star Wars Episodes I and II, concept artist for The Force Awakens, and production designer for Rogue One, paid tribute to Ralph McQuarrie’s immense influence on his own work and the look of Star Wars overall. Chiang stated, “Since I didn’t go to art school, I learned to paint and draw through Ralph’s work. The Art of Star Wars books and McQuarrie portfolios became my textbooks.”

Elsewhere, Lucas wrote, “His imaginary lands had history and his weirder inventions looked plausible.” Indeed, like the best science–fiction artists, every one of McQuarrie’s paintings was imbued with a sense of narrative, an inherent drama hinting at a story you’d like to know. McQuarrie envisioned Tatooine, the dusty desert planet of Luke Skywalker’s childhood. He also designed our beloved characters: Darth Vader, Chewbacca, R2-D2, C-3PO. Darth Vader’s infamous and character-defining mask, for instance, was McQuarrie’s idea: “In the script, Vader had to jump from one ship to another and, in order to survive the vacuum of space, I felt he needed some sort of breathing mask,” McQuarrie told the Daily Telegraph in one of his last interviews. He added a samurai helmet to complement Vader’s flowing black robes, and the iconic character was born.

McQuarrie found the ubiquity of his famous character quite satisfying. (Even people who haven’t seen Star Wars—yes, such people exist—can identify Darth Vader. Vader is even recognizable in flat silhouette!) “It’s interesting to have done something out in the world that everyone looks at all the time,” he said. “You become part of the public happening.”

He also played a significant role in the creation of everyone’s favorite anxious android, C-3PO. His design drew liberal amounts of inspiration from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and the art deco aesthetic, and this early painting was one of the first that Fox executives saw. It also inspired Anthony Daniels, the actor who voiced C-3PO. According to Daniels, he’d been intending to turn down the role, but the evocative painting changed his mind: “He had painted a face and a figure that had a very wistful, rather yearning, rather bereft quality, which I found very appealing.”

In a charming tribute to McQuarrie’s influential role, he was given a cameo in The Empire Strikes Back—briefly portraying Rebel General Pharl McQuarrie. He was uncredited and had no dialogue, but in 2007, Hasbro issued an action figure in General Pharl’s image . . . a must-have for any true McQuarrie fan.

His work continues to inspire and influence the makers of today’s Star Wars. The settings and environments he created—places that lived and breathed their own alien history—still serve as the background to the galaxy, shaping the look of the recent blockbusters The Force Awakens, Rogue One, and The Last Jedi. For instance, his original concept art helped shape the look of the farm where we encounter a very young Jyn Erso in the opening sequence of Rogue One.

Though he is best known for his Star Wars work, McQuarrie created concept art for many beloved science fiction properties. He worked on the 1978 Battlestar Galactica series; he worked with Steven Spielberg to design the alien ships in Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T.; and in 1985 he won an Academy Award for visual effects for his work on Cocoon. *

Though far from a household name, John Berkey (1932–2008) conceptualized one of science fiction’s best-known symbols, familiar to just about anyone with even a passing interest in pop culture: the Death Star of Star Wars fame.

His role in developing the visuals of Star Wars was an early one, as he was one of the first artists to influence George Lucas. Lucas commissioned several paintings from Berkey during the stage where he was still trying to get studio funding to make Star Wars, and Berkey’s conceptualizations of futuristic spacecraft helped Lucas bring his science fantasy to life. Berkey laid the visual groundwork for spacecraft such as the B-wings, Imperial Shuttles, and Mon Calamari ships.

“One of Berkey’s illustrations—a rocket-plane diving down from space toward a gigantic metal world—seems to have especially caught and held the director’s eye,” says designer Michael Heilemann in an essay titled “John Berkey & The Mechanical Planet.” “It would, in fact, be echoed in his film’s climax as squadrons of Rebel X-wing fighters attack the Imperial Death Star.”

Later, Ralph McQuarrie took over the concept art for Star Wars, contributing the lion’s share of the arresting visuals that turned the franchise into a genre-defining hit. But there’s no question that Berkey’s ideas also played a role.

Like McQuarrie, Berkey also worked on Battlestar Galactica (1977). (Certain similarities between Star Wars and Battlestar Galactica then led to a lawsuit, but that’s another story—see this page.) Berkey’s passion for envisioning high-tech and futuristic space vessels has shaped the genre indelibly, deeply influencing our entire conception of space warfare.

SFF art expert and critic Jane Frank describes Berkey’s style as “the perfect balance between painterly impressionism and hard-edged realism.” In The Art of John Berkey, Frank collected more than one hundred of his illustrations and provides a nice overview of his contributions to the genre.

Ironically, Berkey never even saw Star Wars, the site of his best-known work. In 2005, he opined, “I suppose I should see it one of these days.” *

Untitled (1971) by John Berkey, often referred to as “Mechanical Planet” or “Tin Planet.” Tempera, 14” × 14”. The painting was purchased by George Lucas as inspiration.

When Star Wars hit the scene in 1977, it revolutionized science fiction forever. In the wake of the movie’s smashing success, TV and film producers at every studio sought their own swashbuckling space opera. On television, the most successful of these was Battlestar Galactica (1978–1979), the original series created by Glen A. Larson.

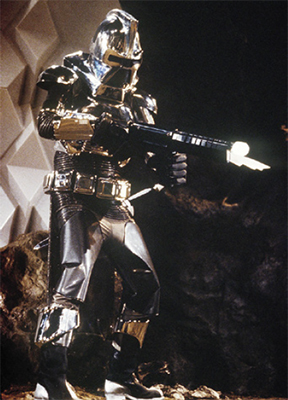

Though not many present-day fans have seen the original Battlestar Galactica, the basic story will be familiar to anyone who saw (or absorbed by osmosis) the more recent twenty-first-century remake by SyFy—after a lengthy battle with the Cylons, the ragtag survivors of humanity flee the Twelve Colonies of Mankind in a massive warship, the “battlestar” Galactica. They journey through space searching for a long-lost thirteenth colony while being relentlessly pursued by the Cylons at every turn. Unlike in the SyFy remake, throughout which the Cylons’ human appearances proved a major plot element, the original Cylons were metallic, humanoid robots—their sleek, bulky exteriors and awkwardly heavy strides not unlike the stormtroopers of Star Wars.

With a 148-minute run time and a $7 million budget, the pilot’s production values rivaled that of a feature film. Narratively and visually, the show’s early episodes delivered similar pleasures to that of Star Wars—and therein lay the problem, as some viewers believed them to be too similar. This camp included George Lucas and 20th Century Fox, who together launched a lawsuit against Universal, months before the show even premiered, based on the courtesy script Universal provided (provocatively titled Galactica: Saga of a Star World).

In its lawsuit, Fox pointed to “34 similarities” between the two properties. Some are eye-rollingly broad, seeming to implicate dozens—if not hundreds—of works in the science fiction genre, particularly in the decades since Star Wars cast its long shadow. Consider “The central conflict of each story is a war between the galaxy’s democratic and totalitarian forces” or “The heroine is imprisoned by the totalitarian forces.” Others are a little more specific, and perhaps damning: “Space vehicles, although futuristic, are made to look used and old, contrary to the stereotypical sleek, new appearance of space age equipment” or “There is a scene in a cantina (Star Wars) or casino (Battlestar), in which musical entertainment is offered by bizarre, non-human creatures.” (Though, to be fair, fans of the French comic series Valérian might argue that the cantina scene wasn’t original to Star Wars, either—see this page.)

Ralph McQuarrie designed concepts for the human fighter spacecraft Vipers, the Cylon Raiders and Basestar, and the Battlestar Galactica itself. The Galactica housed a fleet of about 150 Vipers.

Key characters also bore some resemblance to each other. Starbuck, a male character in the 1978 version, is a fighter pilot whose masculine charm and swagger rival that of Han Solo’s. His more straitlaced friend, the handsome young Captain Apollo, carries a heavy family legacy as the son of military legend Commander Adama; his mother was tragically killed by Cylons. In earlier drafts of the script, Captain Apollo was named Skyler, telegraphing his connection to Luke Skywalker a bit too strongly.

But the resemblance that most strongly struck the average viewer were the visuals. “There’s no escaping how much the original version of Battlestar Galactica looks like Star Wars,” essayist and genre critic Ryan Britt writes for Tor.com. “From the red stripe painted on the fuselage of the Vipers, to the rag-tag worn-out look of the spaceships, to the feathery haircuts of Starbuck and Apollo, a small child or elderly parent in 1978 could have easily squinted at the television and believed this was Star Wars: The TV Show.” It turns out there was a very good reason for these visual similarities. Two key creators lent their considerable talents to both projects, in fact going directly from the set of Star Wars to working for Glen Larson on Battlestar Galactica. Those artists were Ralph McQuarrie and John Dykstra.

Ralph McQuarrie, of course, was the concept artist who created many of the most iconic characters and landscapes in the entire Star Wars saga (see this page); his paintings, drawings, and sketches continue to massively influence the franchise. John Dykstra is a lighting and special effects virtuoso whose company Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) used a new motion-controlled camera that enabled some of Star Wars’s most groundbreaking special effects. For their work on Star Wars, Dykstra’s team won Academy Awards for best special effects and special technical achievement.

Despite the accolades Dykstra would receive, George Lucas wasn’t entirely happy with his work, and ended the contract early—perhaps making Dykstra’s move to Battlestar Galactica all the more contentious. With his new company Apogee (which included several employees from ILM), Dykstra created the visuals and special effects for the Battlestar Galactica pilot, which continued to be used throughout the series.

For his part, McQuarrie developed concept art and paintings for Battlestar Galactica that would set the look of the series—including the Galactica, the Cylon ships, and the vaguely Stormtrooper-esque Cylons themselves.

When the Battlestar Galactica pilot finally aired, the lawsuit was still ongoing. It had also grown more complex, since Universal had promptly countersued Fox, claiming that Fox had in fact stolen Star Wars from them, by plagiarizing a Buck Rogers serial from 1939 as well as Silent Running (1972).

As the lengthy pilot premiered, lines were drawn among viewers and fans: Was Battlestar a rip-off? SF master Isaac Asimov said yes: “Battlestar Galactica was Star Wars all over again,” he wrote in a syndicated newspaper column in September 1978. “I couldn’t enjoy it without amnesia.” The ever-obstreperous Harlan Ellison was also #TeamRipOff, saddling the show’s creator Glen Larson with the nickname “Glen Larceny.” Others found the comparisons superficial, especially as the show progressed, giving it more opportunity to flesh out its characters and expand its plot lines, inevitably treading new territory.

McQuarrie provided early artwork and concepting for the metal-attired Cylon centurions, rudely nicknamed “toasters” in the 21st century remake.

The lawsuit was thrown out in 1980 (by a court that also found the resemblances superficial)—then appealed. Universal eventually settled with Fox for $225,000.

Battlestar Galactica itself only ran for a single season—outlived at the time by the lawsuit that followed it. While initially its ratings were strong, they dropped over the season, leading to its early cancellation. After a massive fan outcry—including a suicide—the show returned briefly as Galactica 1980. This iteration lacked most of the original cast, and was not good.

In 2003, the franchise returned on SyFy, first as a three-hour miniseries and then as a series that ran from 2004–2009, produced by Ronald D. Moore and David Eick. (Plus a handful of spin-offs such as The Plan (2009) and Caprica (2010–2011).) This grittier, sexier reboot staked out a territory far removed from its “Space Western” beginnings; now, comparisons to Star Wars would seem absurd. Yet both properties remain a lasting testament to the conceptual artistry of Ralph McQuarrie, who created the iconic visuals that so thoroughly define each story. *

In Frank Pavich’s award-winning documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013), the famed director himself relays an odd and hilarious story about David Carradine, the actor tapped to play Duke Leto (a lead character). Alejandro Jodorowsky (b. 1929) invited Carradine to meet him in his hotel room. When Carradine walked in, he saw a jumbo-sized jar of vitamin E, which Jodorowsky had purchased “to take one pill every day, in order to have the strength.” As soon as Carradine crossed the threshold and laid his eyes on this delightful prize, he exclaimed, “Oh, vitamin E!” . . . and proceeded to swallow the entire bottle. Here, Jodorowsky does an impression of Carradine’s insatiable vitamin E–gobbling: head tossed back, the imaginary jar pouring its contents straight into his gargling throat. “It was like a monstrosity!” Jodorowsky concludes.

Harkonnen’s Flagship, concept art by Chris Foss for Jodorowsky’s Dune.

This bizarre, unrestrained act signified to Jodorowsky that Carradine could pull off the ambitious role, and he told him, “You are the person I am searching for.”

Jodorowsky is a charismatic, charming figure, and this story, like many of his recollections, is relayed with a fierce vitality that makes it quite enjoyable to watch. It’s very funny. But as he moves on to other topics, some practical questions remain—who in the world, no matter how eccentric, would swallow a hundred vitamin E pills in one sitting? Wouldn’t Carradine need a bit of beverage to wash them down? Did he . . . chew them? How long did this take? What were Jodorowsky and colleagues doing as the situation unfolded?

But no further explanations are forthcoming. This is the story; it is what it is. And this is the spirit in which it’s best to encounter the documentary as a whole, and the larger-than-life legend of the greatest movie never made. It’s a rousing vision, and a fantastic story. Would it have been an equally fantastic film? We’ll never really know.

In the early 1970s, Chilean film director Alejandro Jodorowsky was making major waves in art house and indie film circles. His psychedelic western El Topo (1971) was an early cult film, some say the first “midnight movie.” El Topo was followed by Jodorowsky’s surrealist fantasy film The Holy Mountain (1973), which the New York Times called “dazzling, rambling, often incoherent satire on consumerism, militarism, and exploitation.” So it makes sense that he was tapped to direct the film adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965), a groundbreaking novel to which many of the above descriptions apply. Dune (the novel) is a massive epic of the far future, where the corrupt, decadent villains of the galaxy execute complex political maneuvers in order to control the backwater planet Arrakis (colloquially called Dune). Though a barren and hostile place, Dune is home to an extremely rare element called “spice,” an addictive substance and energy source that’s essential to the function of the entire galactic order—essentially, what fossil fuels were to civilization in the 1970s, combined with a tinge of LSD.

Writing for the Guardian in 2015, novelist and journalist Hari Kunzru said, “Every fantasy reflects the place and time that produced it. . . . Dune is the paradigmatic fantasy of the Age of Aquarius. Its concerns—environmental stress, human potential, altered states of consciousness, and the developing countries’ revolution against imperialism—are blended together into an era-defining vision of personal and cosmic transformation.” Fueled by this timely vision, Dune became one of the bestselling science fiction novels of all time. It won the Hugo and the Nebula (the genre’s biggest awards). As of 2003, it had sold twelve million copies.

A galaxy-spanning epic . . . a worldwide phenomenon . . . Dune was the perfect target for Jodorowsky’s almost limitless vision and ambition. In a 1985 essay on the subject, Jodorowsky wrote, “There is an artist, only one in the medium of a million other artists, which only once in his life, by a species of divine grace, receives an immortal topic, a MYTH.” For him, Dune was that once-in-a-lifetime project. “I had received a version of Dune and I wanted to transmit it,” he writes. “The Myth was to give up the literary form and to become Image . . .”

Terming it “easily the geekiest and most obsessive documentary I saw all year,” Entertainment Weekly’s Chris Nashawaty declared Jodorowsky’s Dune one of the ten best movies of 2014.

In Pavich’s documentary, Jodorowsky articulates similar thoughts: “For Dune, I wanted to create a prophet. Dune will be the coming of a God.”

For such a visionary project, there could be no ordinary cast and crew. Jodorowsky began assembling a team of “spiritual warriors,” each individual painstakingly selected and tirelessly persuaded. Jodorowsky understood exactly the talents he required, and there could be no substitutions, no alternates.

In this way he assembled a truly remarkable creative team: legendary concept artists Jean Giraud (who went by Moebius for his sci-fi work), H. R. Giger, Chris Foss, and artist/writer Dan O’Bannon, all of whom later did outstanding, genre-defining work on Ridley Scott’s Alien. Jodorowsky asked each of these three very different artists to work individually on specific aspects of the set design. This smart move ensured unique aesthetics for galactic actors separated by gulfs of space and time. The Swiss surrealist H. R. Giger, for instance, created the look and feel of the degenerate, depraved world of House Harkonnen, poisoned by their own greed and perversion.

Jodorowsky also recruited Mick Jagger, Salvador Dali, and Orson Welles as actors. His own twelve-year-old son Brontis trained in fighting techniques for six hours a day for two years straight, in preparation for the lead role of young Paul Atreides. Together with avant-garde band Magma, Pink Floyd would create the soundtrack—a work that could have become an unforgettable SF classic in its own right.

Much of Pavich’s documentary is devoted to Jodorowsky describing the bold strategies employed to convert these figures to his cause—and enumerating the various coincidences and serendipities that brought them together. Orson Welles, a legendary foodie, refused his pleas to play Baron Harkonnen until Jodorowsky promised to hire his favorite chef to cook for him every day on set. Salvador Dali invited Jodorowsky to join him at a table filled with Dali’s friends and admirers, then posed a surreal riddle, claiming that he’s often discovered clocks in the sand—has Jodorowsky ever found one? Jodorowsky is momentarily stumped, wanting to seem neither too bereft of clocks nor too boastful, until he hits on the perfect answer . . . he’s never found a clock, but he’s lost plenty. Dali is impressed and agrees to play the emperor. And so on.

Leading his design team with messianic fervor, Jodorowsky would give them a speech each morning: “You are on a mission to save humanity.” As the documentary makes clear, his passion for the project inspired and motivated them, eliciting their very best work. “It was a phenomenally creative period,” said Chris Foss in Skeleton Crew magazine. “Goaded by the guru-like Alejandro, I produced some of my most original work. We were literally a gang of three working under the master to create a multi-million-dollar movie.”

For two years the team worked on sketches, scripts, concept art. Moebius storyboarded out the entire film with Jodorowsky’s direction. All those materials now form a massive—as in unbelievably gigantic—book; allegedly only two of these books exist. We get a glimpse of this book in the documentary, rifling through the pages. Its rarity feels like a bit of a waste. Though it would no doubt cost a fortune to reproduce, it would make a hell of a coffee table book.

Everything was ready to begin filming, but it was not to be. By 1976, Jodorowsky had already spent $2 million in preproduction, and the film as imagined would need a great deal more funding to realize the vision. Not to mention it was intended to be a fourteen-hour-long experience akin to an acid trip. The film’s financial backers got cold feet and pulled the funding, and just like that, the project was over. It was a devastating blow.

A few years later, the rights were acquired by Dino De Laurentiis. De Laurentiis first hired Ridley Scott—who’d recently directed Alien, working with some of the key creative talents involved in Jodorowsky’s Dune. But a family tragedy compelled Scott to exit the project. Next De Laurentiis recruited David Lynch, still a relatively young and inexperienced director.

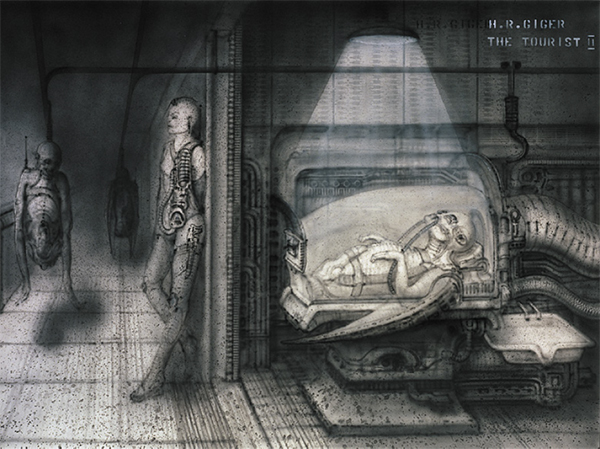

HR Giger: Dune V, 1976, 70 × 100 cm, acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the HR Giger Museum, Gruyeres, Switzerland.

Lynch’s version of Dune is still plenty bonkers. It stars his frequent muse Kyle MacLachlan and the musician Sting. The band Toto took a break from blessing the rains down in Africa to create the soundtrack.

The film is undeniably awful—a fact that cheered the heartbroken Jodorowsky immensely. (As an admirer of Lynch, a kindred creative spirit, Jodorowsky blamed not the director but the short-sighted producers who’d done them both wrong.) Lynch’s Dune cost $45 million to make and only grossed $31 million, a financial disaster. A TV adaptation called Frank Herbert’s Dune premiered on Syfy December 3, 2000; the three-part miniseries was one of the channel’s highest-rated programs and won Emmys for cinematography and visual effects. Writing for Tor.com, Emily Asher-Perrin pronounced it “the Most Okay Adaptation of the Book to Date,” which is, well, something.

In an odd twist, Frank Pavich’s documentary—the best look we’ve ever gotten at Jodorowsky’s Dune—was a hit at Cannes and a classic for fans, winning acclaim and awards.

Now, another adaptation is (hopefully) headed for the big screen. In 2017, Legendary Films hired director Denis Villeneuve to take a shot at it. Villeneuve directed Arrival (2016), a gorgeous, heartrending masterpiece of a film based on a brilliant short story by Ted Chiang. Arrival wowed genre and mainstream audiences alike, winning the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation and receiving Oscar nominations for best picture, best director, and best adapted screenplay (among others). Perhaps Villeneuve is the director to finally conquer this seemingly unconquerable story. *

Imagine this: Men in Black, but darker, stranger, sexier. Star Wars’ Mos Eisley Cantina, but designed by H. R. Giger of Alien fame. A New Wave noir starring an enigmatic bombshell blonde, authored by a female screenwriter. That was “The Tourist”: a 1980 screenplay by Clair Noto that never made it to the screen. If it had been made, it would have been the first film noir science fiction movie, groundbreaking for the innovation that Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner claimed instead. Some have termed “The Tourist” a masterpiece, and it frequently makes appearances on lists of the greatest sci-fi movies never made. But will it ever be more than a dream?

HR Giger: The Tourist II, Biomechanic Bird Robot in His Room, 1982, 70 × 100 cm, acrylic on paper. Courtesy of the HR Giger Museum, Gruyeres, Switzerland.

HR Giger: The Tourist VI, Alien Heads, 1982, 70×100 cm, acrylic on paper, Courtesy of the HR Giger Museum, Gruyeres, Switzerland.

Noto’s previous writing credits included a stint working on Marvel Comics’ Red Sonja. One of her inspirations was the 1951 sci-fi classic The Day the Earth Stood Still, in which an alien walks among us disguised as a human. Another inspiration was the work of H. R. Giger, whose darkly erotic illustrations she followed in the pages of Heavy Metal magazine—making the artist the perfect candidate to render concept art for “The Tourist.”

The script follows Grace Ripley, a gorgeous blonde, a corporate executive, and a secret alien exiled on Planet Earth. An encounter with another disguised alien draws Grace into Manhattan’s seedy underbelly, where alien refugees congregate in a hidden place called The Corridor. The Corridor is home to a variety of extraterrestrials from many worlds; those who aren’t disguised must spend their lives hiding away in this cramped underground slum. The Corridor is part internment camp, part sex club, where aliens get up to the type of kinky shenanigans you’d expect from higher beings stranded on a really boring planet a zillion light years from home. Noto said, “I wanted to portray sexual agony and ecstasy in a way I’d never seen before, and science fiction seemed like the arena.”

Grace navigates this weird secret world in search of a person who is rumored to have a way to leave Earth. The journey brings her face to face with her alien nemesis in a no-holds-barred confrontation.

Influenced by directors Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni, and inspired by the aesthetic of the New Wave, Noto’s screenplay used an unconventional structure. It was a uniquely compelling and highly original work, which immediately captured the attention of directors and producers. In 1980 it was optioned by Universal. Director Brian Gibson, who would soon go on to direct Poltergeist II (1986) oversaw the script development. H. R. Giger, who had just played a major role in the creative design of the highly successful film Alien (1979), began envisioning the alien denizens of the Corridor.

In an interview with film critic David Hughes, Gibson said of “The Tourist,” “What struck me as being totally original was the idea of a rather gloomy, existentialist film noir, with the premise of Earth being a dumping ground for monsters from various galaxies, which was very resonant with a depressed view of the human condition. It made it a movie with art-house appeal, but with a premise that had a much wider potential audience.”

Unfortunately, it was the potential for a bigger audience that sunk the project. The studio wanted to revise Noto’s unconventional script structure into something more appealing to mainstream audiences, as the large special effects budget for this visually lush movie would demand a big investment—in need of a big return. Script doctors struggled to mesh their edits with Noto’s idiosyncratic voice. Creative differences and personality clashes stalled the project.

The screenwriter herself was candid about the script’s structural challenges. “There are certain projects that have a form and a structure to them that any good writer can really come in and deal with,” she told Fred Szebin for Cinefantastique. “This doesn’t have that. It’s all over the place; definitely a can of worms.” But she was content with that approach, drawing as she had on New Wave influences. On this particular script I didn’t give a damn to try to make a mainstream script,” she added. Her characters were also inspired by figures from her own life, a source of creative fodder that future script doctors would not understand.

Noto regained the rights and took the script to Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope. With the wild success of The Godfather and Apocalypse Now, Coppola was already legendary. But Zoetrope was a financial failure. The studio shut down in 1984, and Noto’s script went back to Universal Studios. It spent the following years bouncing back and forth between creative teams, stranded in development purgatory.

Today, almost forty years since Noto first wrote the script, “The Tourist” still has its enthusiastic fans, many of whom would still love to see the screenplay become the film it deserves . . . or even a TV show. With its weird and unsettling atmosphere; its story about xenophobia and alienation, desire and isolation; and its strong female lead, perhaps the time for “The Tourist” has finally come. In the age of all-you-can-watch streaming originals, “The Tourist” might even be the making of Netflix, Hulu, or Amazon’s next big hit. *

From the Alien quadrilogy to TRON to 1980s Marvel, the direct and indirect influence of French artist and illustrator Moebius/Jean Giraud (1938–2012) is widespread and unmistakable. After getting his start in Western-themed comic books as a young artist, Moebius developed a gritty, dark style of realism that caught the eye of film directors who were looking to capture the Spaghetti Western aesthetic, including surrealist Alejandro Jodorowsky for his doomed adaptation of Dune (see this page). Despite that grand film never getting made, the collaboration between Jodorowsky and Moebius led to the creation of a dark surrealist graphic novel (Les yeux du chat) that brought Moebius further into the worlds of science fiction and fantasy. Later, the two would collaborate on another—and better-known—French graphic novel series, The Incal, first published from 1980 to 1988 in the French science fiction/horror comics magazine Métal Hurlant. Written by Jodorowsky and illustrated by Giraud, The Incal is a baroque and expansive space opera that centers on the adventures of an archetypal “everyman” character named John DiFool. After a move to California, Moebius made art for well-known DC and Marvel titles, including Batman, Iron Man, Static, and a Silver Surfer miniseries written by Stan Lee that won the Eisner Award for limited series in 1989. Moebius’s style had a subtle influence at both houses, incorporating a grittier, more heavily textured technique than most of the illustrators of the decade.

Jean Giraud in conversation with journalists at the 26th Edition of the International Comic Show in Barcelona, April 2008. Photo credit: Alberto Estevez/EPA/Shutterstock.

The artist enjoyed a long run of successful projects in Hollywood after having made a name for himself in the United States. Moebius contributed character design and storyboard art for such blockbusters as Alien, TRON, The Abyss, and The Fifth Element. His style is as visible and as commonly imitated in 1990s science fiction as his contemporary H. R. Giger, though the latter is more commonly cited as the visionary artist responsible for the terror of facehuggers and chest-bursters. Moebius’s work did not emphasize body horror, but it was just as instrumental in visual worldbuilding.

Not only a visual artist, Moebius wrote the story and created the conceptual art for Yutaka Fujioka’s 1989 animated film Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland, and wrote a graphic novel series for the same story five years later with artist Bruno Marchand.

The artists and directors who claim Moebius as a major influence on their work reads like a who’s who of the twentieth century. George Lucas tried to get Moebius to work with him on Willow, only to lose him to other projects and regret the loss for years afterward. He has been cited as an inspiration by Neil Gaiman, Federico Fellini, Paulo Coelho, Mike Mignola, and Hayao Miyazaki. Ridley Scott counted himself lucky for having had Moebius’s input on the Alien franchise, and continued to cite his importance through Blade Runner and the whole genre of science fiction in film.

Moebius was eulogized by the French minister of culture at his 2012 funeral, described as a double loss to the French arts: both as Giraud and as Moebius. The artist is interred at Paris’s elite Montparnasse Cemetery, where many of the greatest figures in the country’s history are laid to rest.

But an artist never truly dies, so long as their work and the works that they touched live on. In his own words, Moebius admitted that he had become something legendary and uncatchable in a much-quoted moment of self-description acknowledging the effect he has had on the many different worlds in the art realm:

“They said that I changed their life. ‘You changed my life. Your work is why I became an artist.’ Oh, it makes me happy. But you know, at same time I have an internal broom to clean it all up. It can be dangerous to believe it. Someone wrote, ‘Moebius is a legendary artist.’ That puts a frame around me. A legend—now I am like a unicorn.”

Moebius is a unicorn. You may not know what you saw, but you know you saw it. You never forget. *

Remember WarGames?

In this 1983 movie, a computer-savvy teen, played by the always lovably dopey Matthew Broderick, accidentally hacks into a computer at the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) while searching for fun new games to play. The computer challenges him to a game of “Global Thermonuclear War.” Enthusiastically, Broderick agrees, and unintentionally sets off a nuclear crisis that could launch World War III.

WarGames got a 21st century follow-up with the 2009 sequel, WarGames: The Dead Code. The movie went straight to DVD and, with a 25% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, was not a hit.

“As a premise for a thriller, this is a masterstroke,” the late, great film critic Roger Ebert wrote in his review. Even today the film is a fun watch, even if such a thing could certainly never have happened. The very premise is patently ridiculous . . .

Or is it?

President Ronald Reagan wondered the same thing. And the terrifying answer changed the future of cybersecurity.

As a former film star himself, Reagan loved watching movies. He saw the film soon after it came out during some relaxation at Camp David. When he returned to the White House, he was scheduled to meet with national security advisors and senior members of Congress. The meeting agenda focused on forthcoming nuclear arms talks with Russia.

But Reagan was still thinking about WarGames. He interrupted the talk of Russia to ask his assembled national security advisors what they thought of the film. No one else had seen it yet, so he gave them the play-by-play, describing the film in detail while his audience listened in confusion.

In a retelling of the event, cybersecurity expert Fred Kaplan writes, “Some of the lawmakers looked around the room with suppressed smiles or raised eyebrows. Three months earlier, Reagan had delivered his ‘Star Wars’ speech, imploring scientists to build laser weapons that could shoot down Soviet missiles in outer space. The idea was widely dismissed as nutty. What was the old man up to now?”

Undeterred, Reagan asked his chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General John W. Vessey Jr. to investigate a key question: “Could something like this really happen?”

Vessey did. And his findings were . . . concerning. “Mr. President,” he’s reported as saying, “The problem is much worse than you think.”

As it happens, the movie’s shocking premise didn’t just emerge from the fevered mind of a screenwriter. When Lawrence Lasker and Walter Parkes were writing the screenplay, they interviewed one of the world’s foremost experts on computer security—an engineer named Willis Ware.

Ware had actually helped design the NORAD computer’s software (so he knew exactly what Broderick was getting into). He’d written a paper on the system’s vulnerabilities way back in 1967. Like Cassandra, he’d been warning fruitlessly about a life-and-death hacking scenario for decades. But when the story was brought to life by WarGames, the threat finally captured America’s attention . . . as well the president’s.

Fifteen months later Reagan signed a classified national security decision directive, the “National Policy on Telecommunications and Automated Information Systems Security.” And cybersecurity was born.

WarGames did pretty well, too, earning $80 million at the box office, not bad for a film that only cost $12 million to make. It even got three Oscar nominations, including one for Lasker and Parkes’s original screenplay.

WarGames’ concluding line, “A strange game. The only winning move is not to play,” tapped into America’s Cold War–weary zeitgeist. But the film’s lasting legacy is intimately connected with the cybersecurity concerns of today. *

In James Cameron’s Aliens (1986), Sigourney Weaver reprised her role as Ellen Ripley, reliving her greatest trauma as she joins a mission to the planet where the aliens were discovered—and now, it seems, are wreaking havoc. There, she discovers a small, terrified girl, the settlement’s last survivor. Like Ripley, Newt has suffered unimaginable horrors through her encounters with the aliens; like Ripley at the end of Alien (1979), she’s the only one left. Their relationship offers a powerful narrative thread as Ripley, the marines, and an android named Bishop take on one nasty beast after another.

The movie was a smashing success, receiving accolades from viewers and critics alike. It was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won two. (And Sigourney Weaver was nominated as best actress for her role, rare recognition for a science fiction film.) Despite the fact that it was made for only $18 million, it brought in $180 million worldwide, an impressive return on investment.

Unfortunately, Alien 3, the second follow-up from 1992, did not garner such praise. Though it wasn’t a complete flop, reviews were mixed, and it did not enjoy the same commercial success. Its director, David Fincher, has since disowned it.

But, as journalist Abraham Riesman phrases it mournfully in Vulture, “there’s an alternate universe where the series’ propulsive momentum only increased . . . the alternate universe where legendary science-fiction writer William Gibson’s Alien III (that’s “III,” not “3”) screenplay was realized. It is, perhaps, a better world than ours.”

When Aliens came to theaters in 1986, novelist William Gibson was a hot young talent and rising star; his first novel, Neuromancer, had been published in 1984 to wide appreciation. Unknown to the makers of Alien, the “dirty spaceship aesthetic” of the first movie had already found its way into his fiction, shaping the gritty world of Neuromancer’s Sprawl. In 1992, speaking of the original Alien movie, Gibson told Cinefantastique, “I thought there were germs of stories implicit in the art direction. I always wanted to know more about those guys. Why were they wearing dirty sneakers in this funky spaceship? I think it influenced my prose SF writing because it was the first funked up, dirty kitchen-sink space ship and it made a big impression on me.”

This latent influence spawned an ironic but charming loop. As Douglas Perry described it in Cinescape in 1995, “[David] Giler had read Gibson’s award-winning novel Neuromancer and realized with a jolt that the futuristic Earth the novelist envisioned jibed perfectly with the exhausted techno-society represented by the Nostromo and its crew in Dan O’Bannon’s original story.” Giler and his fellow producer Walter Hill offered Gibson a chance to write the screenplay, and he accepted.

There was a catch, however. Sigourney Weaver would not be able to appear in this film; contractual disputes may have played a role, as she did eventually return as Ripley in the real-world version of Alien 3. Ripley was such a powerful protagonist in the first two films, and it would be a challenge to reinvent the narrative without her. Instead, Gibson chose to focus on his second-favorite character from Aliens; the android, Bishop. Giler and Hill gave Gibson a basic treatment for the story and sent him off to work.

In a way, Gibson seems an odd choice for a screenwriter. What is most brilliant and striking about his body of work is his talent for evoking a world through language. He has a talent for description that cascades in glittering onslaughts of synesthesia that cut like a diamond. You see and feel and taste his worlds, even the indefinable and ambiguous space of virtual reality (or as it’s termed in his Sprawl trilogy, “the matrix”). The opening sentence to Neuromancer is one of the most famous in science fiction: “The sky above the port was the color of a television, tuned to a dead channel.” For a virtuoso of description like Gibson, the screenplay format seems like a waste of his talents.

Nevertheless, Alien III is a very solid story. Though his script was never translated to the big screen, the visual moments it evokes come through powerfully enough that your imagination fills in the gaps; there are scenes that one can picture so completely that it’s as if you really watched them. The description that follows is based on Gibson’s first draft, which can be read in its entirety online, offering it a kind of lasting narrative life of its own.

The script picks up where Aliens left off. In the closing minutes of that movie, only a few have survived the carnage on the planet where the xenomorphs were first discovered. The last characters standing are Ripley, a marine named Hicks, the loyal android Bishop, and a little girl named Newt. This small band of survivors has made it to their ship, the Sulaco, ready to get the hell out of this place. But the Xenomorph Queen has stowed away for one last major battle. Her massive stinger rips apart Bishop, separating his torso from his legs. Despite the severe damage, his upper body continues to function. Ripley and the Queen go head-to-head in a major showdown, as Ripley risks everything to save Newt, her surrogate daughter. The Alien Queen is ejected into space and the team survives. They go into hypersleep and head back toward Earth.

Gibson’s Alien III opens on the Sulaco drifting in space. Ripley, Hicks, Newt, and the wounded Bishop are unconscious in their hypersleep capsules, oblivious to the navigation error that sends their ship into a disputed sector of space, claimed by the Union of Progressive Peoples (U.P.P.)—a Communist coalition that serves as an obvious stand-in for the 1980s Soviet Union and its satellite states.

A passing U.P.P. ship stumbles on the Sulaco and sends a small boarding party to check it out; an eerie, voyeuristic moment ensues, as the slumbering Sulaco crew has no idea they’re being boarded and observed by enemy soldiers. “Commandos move down the line, guns poised,” reads the script. “They peer in at Newt, Ripley, and Hicks, but the lid of Bishop’s capsule is pearl-white.” They open the capsule to discover an Alien egg rooted in Bishop’s wounded torso. Seconds later, a feisty, well-rested face-hugger ejects itself and attaches to their Leader’s head. His soldiers manage to shoot it without killing him but the alien’s acidic body fluids spew everywhere and burn through his helmet. The commandos grab Bishop’s torso and scramble back to their own ship.

The next sequence opens on a space station called Anchorpoint, “the size of a small moon, and growing”; “a vast, irregular structure, the result of the shifting goals of successive administrations.” The Sulaco has just docked, with the team still in hypersleep. Tissue culture lab tech Tully is called in the middle of the night to come take samples and basically figure out what the deal is. Mysteriously, a couple of high-ranking people from “Millisci, Weapons Division” have also arrived . . . and the plot thickens.

Accompanied by a couple marines, Tully heads onto the Sulaco to collect atmosphere samples. Of course, just as they arrive in the hypersleep chamber, some unwelcome visitors arrive. Alien stowaways attack the marines, who barely manage to escape, hosing down the entire chamber with liquid fire from their flamethrowers. (In Gibson’s second draft, this scene is omitted entirely, which is probably for the best as it’s not entirely clear why or how the full-sized xenomorphs were roaming around the ship.)

In Anchorpoint’s medical clinic, Hicks and Newt meet lab tech Spence, Tully’s girlfriend; she will be one of the key players in this story. In accordance with Gibson’s parameters, Ripley remains in a coma, stuck in the interminable nightmare of Alien carnage.

This leads to one of the story’s most poignant moments. Newt stands beside the bed of the unconscious Ripley, “monitored by assorted white consoles. Her forehead is taped with half a dozen small electrodes.”

“She’s sleeping,” Spence tells Newt. “Sometimes people need to sleep . . . To get over things . . .”

“Is Ripley dreaming?” Newt asks.

“I don’t know, honey.”

“It’s better not to.”

William Gibson’s Alien 3 #3, written by William Gibson and Johnnie Christmas, illustrated by Johnnie Christmas. Published by Dark Horse Comics in 2019.

This short exchange encapsulates so much of what’s gone before; the unspeakable trauma of survival, the cosmic dread the aliens represent, and the unshakeable bond formed between Ripley and Newt, who’ve each lost all except each other.

It also exposes the script’s fundamental weakness. This early moment touches on deeper emotion than anything that follows. Newt gets shipped back to her grandparents on Earth, Ripley never wakes up, and the emotional stakes that remain are ambiguous. Every other character may as well be cannon fodder; as it turns out, the vast majority of them are.

Back on the U.P.P.’s Rodina, the Commies are mining Bishop’s torso for data, learning all about the aliens. Meanwhile, in a clever cut shot, technicians on Anchorpoint are extracting similar biological information from Bishop’s legs. Something unexpected is happening, and here, Gibson introduces an idea that in the real-life history of the franchise wouldn’t emerge until 2012, in the prequel Prometheus. Gibson imagines the Alien Queen as a biological weapon, leaving behind an instinctually hungry residue that’s as fiercely desperate for survival as its eggs. (The “black goo” in Prometheus is not alien residue, but the concept is similar; a biological substance that bends and mutates other living matter to its will and remakes it in its own image.)

The scary Millisci folks who’ve arrived on Anchorpoint are interested in exactly that. They inform Colonel Rosetti, Anchorpoint’s head of military operations, that scientific testing will continue on the aliens’ bizarre genetic material. (“The alien genetic material looks like a cubist’s vision of an art deco staircase, its asymmetrical segments glowing Dayglo green and purple,” Gibson writes.) Rosetti protests that such testing is in violation of weapons treaties. In a wink-wink manner, the Millisci people tell him the experiments are for cancer research. “We’ll nourish the cells in stasis tubes, under constant observation,” one says. Back on the U.P.P. Rodina, they’re doing the same thing.

The Millisci command also insists that Tully, the marines who originally boarded the Sulaco, and anyone else who knows about alien shenanigans be forced to sign a rigorous nondisclosure agreement.

But silence breeds death. A number of people have already been exposed to the alien DNA. As Rodina and Anchorpoint play politics over the safe return of Bishop, and insiders and outsiders on Anchorpoint jockey for power, the infection is spreading beneath the surface. And it bursts forth in a spectacular fashion at a meeting of Anchorpoint’s top brass, when one of the Millisci bad guys, a woman named Welles, is interrupted mid-evil-monologue to transform into something horrifying. This ain’t a chest-burster; it’s more like a whole-other-being-burster.

“Segmented biomechanoid tendons squirm beneath the skin of her arms. Her hands claw at one another, tearing redundant flesh from alien talons. . . . She straightens up. And rips her face apart in a single movement, the glistening claws coming away with skin, eyes, muscle, teeth, and splinters of bone . . . The New Beast sheds its human skin in a single sinuous, bloody ripple, molting on fast forward.”

This point occurs about halfway into the script, and from that point forward, it’s pretty much nonstop carnage, with people molting into New Beasts left and right, and the loose New Beasts doing plenty of damage themselves. The same thing is occurring over on the Rodina, which calls for help from its comrades, who come quickly—to obliterate the entire ship with a nuclear missile. An effective containment strategy, no doubt. Only one female commando escapes in the small shuttle first used to board the Sulaco.

On the Anchorpoint, Tully goes down, leaving Spence, Hicks, and the recently returned and fully repaired Bishop to lead a band of soldiers and crew on a perilous journey through the station to reach the lifeboat bay. The remaining sequences are pure action, as New Beasts pick them off one by one and the brave crew dwindles to nothing. Meanwhile, Bishop departs on a secret solo mission to hack the fusion reactors on the station to blow the whole thing, leaving just enough time for their escape. There are bloody, acid-bathed battles, claustrophobic tunnel sequences, and people getting skewered by alien stingers at the most dramatically ironic moments; all the things we know and love from Alien and Aliens. On the big screen, this would no doubt be fast-paced, heart-pounding, and exquisitely satisfying, but on the page it can be a bit hard to follow.

There are implications that the alien DNA isn’t just colonizing the people, but the ship itself. As in a side trip through a hydroponic farm, where “two of the Styrofoam structures have been overgrown with a grayish parody of vegetation, glistening vine-like structures and bulbous sacs that echo the Alien biomech motif. Patches of thick black mold spread to the Styrofoam and the white deck.”

Another compelling scene sees Spence revisiting the Anchorpoint’s eco-module, described in earlier scenes as “an experimental pocket Eden . . . lush rainforest, sun-dappled miniature meadows, patches of African cactus.” Once an idyllic refuge, the eco-module is now poisoned by the aliens, too. The primates are cocooned, poised to hatch. The lemur has become an alien itself, screaming and pouncing from the trees above. As it represents the Anchorpoint’s downfall, this arc also foreshadows the unthinkable, which has remained a source of ultimate dread throughout the franchise: What if the aliens make it to Earth?

In the story’s tense final moments, the U.P.P. commando arrives at the rescue. Hicks, Spence, and Bishop are the only survivors who make it onto her shuttle. (The still-unconscious Ripley was previously launched to safety in a lifeboat.) As Hicks and Spence try to comfort the commando, who is dying from radiation poisoning, Bishop observes, “You’re a species again, Hicks. United against a common enemy . . .”

But this particular version of Alien III would never be made (at least not into a film). Perhaps the producers had hoped for something more strikingly cyberpunk; perhaps they didn’t know exactly what they were hoping for, but this wasn’t it. David Giler told Cinefantastique, “We got the opposite of what we expected. We figured we’d get a script that was all over the place, but with good ideas we could mine. It turned out to be a competently written screenplay but not as inventive as we wanted it to be. That was probably our fault, though, because it was our story.”

Gibson’s script was followed by about thirty others. In the end, Alien 3 was based on a script by independent filmmaker Vincent Ward, although some significant changes were made to his story. This is a secret history all its own, as Ward’s original concept is also a famous unmade version—perhaps more famous, as it came much closer to being fully realized.

In Ward’s treatment, the penal colony where Ripley crash-lands in Alien 3 was originally meant to be, in Gibson’s words, “a wooden space station inhabited by deranged monks.” It’s also a fascinating take on the franchise. As pop culture critic Ryan Lambie describes it on Den of Geek, “when Ripley lands on the planet in an escape vessel, the horrors she brings with her are, from the monks’ perspective, straight from the depths of hell: the chestburster erupts from its victims like a demon. The full-grown alien is regarded as a dragon, or perhaps even the Devil himself.” Concept art was created by artist Mike Worrall and architectural designer Lebbeus Woods; the wooden sets were even built. Then the film’s release date was moved up and the producers decided to scrap the baroque weirdness and go with the more conservative setting of a prison planet. The frustrated Ward, who’d aspired to do something more ambitious with the story, then exited the production.

In 2018, it was announced that Gibson’s Alien III would be getting a second life. Dark Horse Comics is creating a five-part comic series based on the script, adapted by talented writer/artist Johnnie Christmas. “When your first contracted screenplay (or screenplay of any kind, in my case) isn’t produced, but the film is eventually made with a different screenplay, retaining nothing of yours but a barcode tattoo on the back of a character’s neck, the last thing you ever expect is to see yours beautifully adapted and realized, decades later, in a different medium, by an artist of Johnnie Christmas’s caliber,” William Gibson told CBR. “It’s a wonderful experience, and I have no doubt that Johnnie’s version, which adheres almost entirely to the script, delivers more of my material to the audience than any feature film would have been likely to do.” Christmas’s past work includes the critically acclaimed Sheltered (Image Comics) and a collaboration with legendary writer Margaret Atwood on a graphic novel series Angel Catbird. It will be a pleasure to see his interpretation of Gibson’s script. *

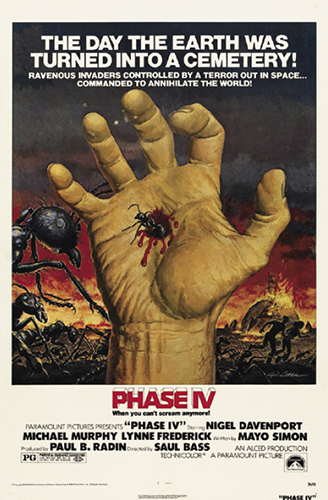

Phase IV (1974) could’ve been another schlocky, nature-run-amok B movie. Instead, it’s a strange, daring film full of big ideas and stunning imagery that informs speculative film/fiction four decades later.

The movie’s director, Saul Bass, was a legendary graphic designer and artist, credited as the founder of modern title design. A short list of his iconic title sequences include: The Night of the Hunter (1954), Vertigo (1958), West Side Story (1961), Goodfellas (1990), and both Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Gus Van Sant’s curious (to be kind) remake (1999). In the original Psycho, Bass’s credits also included “pictorial consultant.” If you’re looking to make a deep Internet dive, go read about Bass claiming he directed the infamous Janet Leigh shower scene, offering his detailed storyboards as proof. Bass also won an Oscar for directing a short documentary film in 1969. Phase IV (1974), however, was the only feature length film he directed, as it bombed at the box office and initially received tepid critical response.

For a movie about killer ants, Phase IV was surprisingly heavy on the arthouse aesthetic, with surreal montages and inventively artsy shots.

The film opens with a deep space vista, replete with glowing galaxies, organ music to make the band Iron Butterfly jealous, groovy morphing colors, and an eclipse. The bright sun contrasted by its negative, which appears to be a black hole in space and time, is a visual motif that is repeated throughout the film. Via voiceover narration, Michael Murphy’s character Dr. Lesko (a code-breaking mathematician-cum-biocommunicator, able to translate whale calls and whistles) speaks of a mysterious cosmic event, one we were able to observe and one many feared would result in worldwide catastrophes. All was quiet on earth until, well, ants. Yes, the nameless, unknowable cosmic event wakes not the usual monstrous candidates (Lovecraftian squids and cephalopods), but jumpstarts global consciousness within the ants. The twitching trillions begin interspecies communication and cooperation. The resulting uber-hivemind is as alien as it is a formidable hyper-intelligence.

For the first nine minutes of the film, Dr. Lesko’s voiceover is the only human on or offscreen. We get an ant-only extended jam (way more organ music) as we watch them swarm and crawl through their labyrinthine nests, antennae and legs twitching. We eventually find the queen’s royal chamber, her head adorned in nature’s version of a crown, and as the camera pans down the length of her body, we see her laying eggs from a grotesquely large, translucent sac. (Flash-forward twelve years to when Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley first sees the queen alien in James Cameron’s Aliens (1986), and that scene plays like a shot-by-shot repurposing of Phase IV’s hail to the queen.) Otherworldly and hypnotic, Bass’s direction shows us these earthbound aliens interacting and planning, and he creates an ineffable sense of their culture without ever anthropomorphizing the creatures. It’s an unsettling and thrilling trick, managing to propel the first-act narrative through the ants while demonstrating the alien-ness of their group intelligence.

At the behest of the United States government, Dr. Lesko joins the maniacal Dr. Hubbs in a chunk of ravaged Arizona desert where ants have run amuck (that’s an entomological term). The two scientists hole-up in a white geodesic dome, stationed near a chorus of obelisk-like ant hives. The scientists attempt contact with the ants and when that doesn’t work, Dr. Hubbs provokes aggression by destroying the hives. Science fiction horror ensues, including a truly disturbing scene in which the scientists press the “yellow” button and accidentally poison a family of farmers who did not evacuate in time. Kendra, the farmer’s doe-eyed granddaughter, survives and becomes a third tenant of the dome.

The ants remain more than a few steps ahead as the humans succumb to the desert heat, paranoia, fear, and moral philosophizing. Dr. Hubbs (imagine a British, hirsute Jack Nicholson) loses what little he has left of his mind, and Dr. Lesko manages rudimentary communication with the ants using really old computers, audio wavelengths, and basic geometric shapes and concepts. It’s not quite an Arrival (2016) level of linguistic theory in play here, but for the purposes of this essay, it’s close enough.