Chapter 3

From Human Progress to Universal Evolution

The double vision we inherited from nineteenth-century science, of evolution on Earth within a physical eternity, is rooted in a far older cultural duality. It reflects the double cultural heritage of Europe: on the one hand the intellectual traditions of Greece and Rome, and on the other hand the Christian faith. The eternities of physics are rooted in our Greek heritage, and our faith in progressive development in the religion of the Jews.

In the medieval synthesis of these two traditions, humanity was believed to undergo a progressive historical development through God’s revelation of himself in historical events and through faith in God’s purposes. But the rest of the world did not progress: the nature of nature was constant.

By the end of the eighteenth century, faith in human progress through the increase of human understanding was widespread; the advance of science itself strongly reinforced this faith, as did the growing industrial revolution. But still the old division held: humanity progressed, but the natural world did not.

As the nineteenth century wore on, a great new vision of progressive development opened up: not only human beings but all living things were seen to have evolved. But the theory of evolution was kept down to earth.

Now, finally, the entire cosmos is thought to have grown and developed in time: all nature is evolutionary. We can no longer think of nature under the aspect of eternity.

In this chapter, we look at the religious roots of the faith in human progress; at the way the concept of progress led to an evolutionary conception of all life on Earth; and at the Darwinian attempt to fit evolution into a mechanistic world. We end by considering the possibility of a new evolutionary synthesis in which the evolution of life is one aspect of the cosmic evolutionary process.

Faith in God’s purposes

The Greek philosophers, like the philosophers of other ancient civilizations, generally thought of time in terms of endlessly repeated cycles: cycles of breathing, of day and night, of the Moon, of the year, great astronomical cycles of years, and great cycles of cycles. In some Hindu systems, for example, a great cycle or mahayuga lasts for 12,000 years; and beyond this are further cycles, up to the great cycle of Brahma comprising 2,560,000 mahayugas.1

Almost all the ancient theories of great cycles of time were found in combination with myths of a golden age. Each cycle starts with a golden age, followed by successive ages of decadence and degeneration in all things. At the end of the last age of the cycle the world undergoes a general dissolution and is then regenerated. There is a new golden age, and so on in an eternal recurrence.2 Hindu and Buddhist philosophies see life itself in terms of repeated cycles of birth, growth and death, with human lives passing through successive cycles of rebirth. With a similar consistency, the Pythagoreans believed in reincarnation, and so did Plato.

By contrast, in the Judaeo-Christian tradition there is just one process of development in time. The Bible begins with the story of the creation, when ‘God created the heavens and the earth’, and ends with the vision of the new creation in the book of Revelation: ‘I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away.’3 The whole story of the Bible is thus set within a cosmic vision of creation, destruction and recreation. But this is not part of a system of eternal recurrences: the new creation of the book of Revelation is not followed by another stage of dissolution, but is the consummation of all things, in which the whole creation is taken up into the divine life, passing beyond its present state of existence in space and time into a final state of fulfilment.4 The six days of creation in the book of Genesis represent the week of time and of earthly activity, while the seventh day is the day of eternity when all labour ceases.

This is the Judaeo-Christian ‘myth of history’.5 It starts, like many other myths, with a golden age – our first parents in the Garden of Eden in harmony with each other, with the world and with God. Then comes the Fall, through the eating of the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, and the expulsion from Eden into a world of toil, suffering and death. But then a great journey begins towards a new Eden, towards the new country promised by God.

The prototype of this historical process was the journey of the people of Israel out of captivity in Egypt, through the sufferings in the wilderness and the covenant with God, and to the promised land. This metaphor of the journey underlies the concept of progress, of going forward. There can be no going forward unless there is a direction in which to advance; and journeys have a direction because they have a destination or goal.

A belief in progressive development was not absent from the ancient civilizations. Indeed, cities themselves were seen to be an advance over the primitive or barbarous state of man. The evidence was there for all to see in the splendour of the buildings, in the advances in the arts and the skills of artisans, and in the organization of empires.6 But the development of civilization was set against the myth of decline from the golden age. The future could only hold even further decadence and destruction.

By contrast, in the Judaeo-Christian tradition there was an intense religious faith in the future. As the Epistle to the Hebrews expressed it:

Faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen … By faith Noah, being warned of God of things not seen as yet, moved with fear, prepared an ark to the saving of his house … By faith Abraham, when he was called to go out into a place which he should after receive for an inheritance, obeyed; and he went out, not knowing whither he went … These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth. For they that say such things declare plainly that they seek a country. And truly, if they had been mindful of that country from whence they came out, they might have had opportunity to have returned. But now they desire a better country, that is, a heavenly: wherefore God is not ashamed to be called their God, for he hath prepared for them a City.7

According to one current of Christian faith, based on the authority of the book of Revelation, after his second coming Christ will establish a messianic kingdom here on Earth and will reign over it for a thousand years, until the Last Judgement. This is the millennium. At intervals throughout Christian history, millenarian groups of believers have sprung up over and over again. A characteristic of millenarian faith is a belief in the imminent coming of a new age here on Earth, not just in some other-worldly heaven, and not just for individual souls. The salvation of the faithful will be collective, and life on Earth will be totally transformed.8

A strong millenarian faith in the imminent coming of God’s Kingdom filled many of the Puritans in seventeenth-century England. In this faith the Pilgrim Fathers left the old country for the new – a New England in the New World. In England itself, the king was beheaded and the old order overthrown; and it was in this revolutionary atmosphere that an entirely new vision of the coming of a new age on Earth began to develop: a transformation of the world through human progress, with science in the vanguard.

Faith in human progress

The prophet of this new vision was Francis Bacon. In New Atlantis, written in 1624, shortly before his death, the new age became a kind of scientific utopia. The advancement of ‘the whole of mankind’ would be achieved through man’s dominion over nature by mechanical means. Only scientific knowledge, founded on the empirical method, could further the ambition ‘to endeavour to establish and extend the power and dominion of the human race itself over the universe’, as Bacon put it. In this way, the human race could ‘recover that right over nature which belongs to it by divine behest’.9

In New Atlantis, progress was guided by a group of researchers who studied nature by the experimental method. Nature was to be forced to give up her secrets, so that they might be used to benefit mankind.10 These investigators worked in a prototypic scientific research institute called Salomon’s House, wore special robes and were a kind of scientific priesthood.

In England, during the revolutionary regime of the Puritans, such a visionary group of scientists and philosophers began to meet informally. This group, known as the Invisible College, formed the nucleus of the Royal Society, founded in 1660, soon after the restoration of the monarchy. Here, in the ‘Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge’, was a deliberate realization of Bacon’s vision. The Royal Society was Salomon’s House. Similar bodies were subsequently established as state academies of science throughout the Western world.

The successes of science and the growth of new industries increasingly strengthened faith in scientific progress, and this faith continually grew and spread – in the eighteenth century throughout Europe and America; in the nineteenth century throughout the empires of the European powers; and in the twentieth century to the remotest corners of the Earth. Where Christian missionaries failed, the missionaries of technological progress succeeded.

This faith was carried from its homelands in the West in Marxist forms throughout the Soviet Union and China; in capitalist forms to Japan and the Far East; and finally to all the nations of the world, which consequently became ‘developing countries’. The process of conversion has now been extended to the remotest villages and tribes through education, economic development and the electronic media.

The aspiration for progress helps to make development happen. And even for those without education, there is compelling evidence of industrial progress everywhere. Where in the modern world are there no radios, for example, or mobile telephones? And where in the world had anything like them ever been seen before? They are not just repetitions of things that have always been known; they are truly new. Through science and technology things are happening that have never happened before.

We may of course wonder whether all such changes are truly progressive. Nevertheless, whether we like it or not, the processes of accelerating change all around us are born out of a faith in progress, a faith that is still very strong. But the ideal of the transformation of the world through scientific progress is only one version of millenarianism. We live also within the fields of others.

The Pilgrim Fathers founded New England in the seventeenth century in a millenarian spirit. The revolutionary political movements of the late eighteenth century were millenarian: the old order would be overthrown and a new era established, an era of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity, in the words of the slogan of the French Revolution. And the vision of a new age was built into the foundations of the newly formed United States and proclaimed on the Great Seal: Novus ordo seclorum, a new order of ages. It can be seen on every dollar bill.

Communism was another expression of messianic faith. Neo-liberalism is yet another, with its promise of universal prosperity through globalized free-market capitalism.11 During the Cold War, the great millenarian powers of the Soviet Union and the United States confronted each other in continuous preparation for an apocalyptic war. Although the Cold War came to an end, nuclear weapons are still with us, and now the world faces great economic uncertainties and climate change as well.

In the last days of this age, according to the book of Revelation, there will be plagues, the casting down of fire, darkness over the Earth, a great war in heaven – and much more. The apocalyptic aspect of the Judaeo-Christian vision of history has not gone away: on the contrary, it has taken on a new and dreadful plausibility as a result of science, technology and economic development themselves.

Progressive evolution

The progress of science took place within a larger vision of human progress, which itself developed in the context of a religious faith in God’s guidance of history towards a new creation. In the course of the nineteenth century, this vision of progressive development was extended to encompass the whole of life on Earth. The evolution of science paved the way for the science of evolution.

By the end of the eighteenth century, it had become obvious to many Europeans and Americans that human progress and the increasing power of man over nature were taking place through the growth of human understanding and above all through science and technology. But was this progressive development in accordance with God’s purposes, and was it guided by God’s will? Many people believed that it was, and many still do. But for the atheists of the Enlightenment, human progress was the achievement of human reason itself. Human reason was the supreme form of consciousness in a mechanistic universe, and human purposes were the only purposes there were. In the French Revolution, the churches of Paris were closed, and the cathedral of Notre Dame was transformed into a Temple of Reason.

But if human reason was developing, how and why was it doing so? In the early nineteenth century, the philosopher Hegel found an answer in terms of dynamic processes of progressive development. Hegel saw the evolution of human thought as an aspect of the process of the Absolute, or in religious language the manifestation of God, through a rhythmic process of developing wholeness. Each such process starts with an initial proposition, the thesis; this proves to be inadequate, and generates its opposite, the antithesis. This in turn proves inadequate, and the opposites are taken up into a higher synthesis. The synthesis leads to a new thesis, to which a new antithesis springs up, and so on.

Hegel’s system proved to be self-fulfilling; to his thesis, Karl Marx opposed the antithesis: not spirit but matter develops dialectically. Dialectical materialism in the tradition of Marx and Engels was a progressive, evolutionary philosophy that regarded historical progress as governed by objective, scientific laws. Human progress was just one aspect of the general progressive development of matter, from which mind itself arose.

In the evolutionary philosophy of Herbert Spencer, progress was the supreme law of the universe. Spencer, like Marx, was interested primarily in human progress; his philosophy of universal evolution was a grand generalization that enabled human evolution to be seen as an aspect of a universal process. Spencer and other nineteenth-century philosophers of evolution, such as C.S. Peirce (above), were proposing a sweeping vision of evolution as a universal process long before an evolutionary cosmology became orthodox in physics. Thus the idea of evolution started life in evolutionary philosophies; only later did it become the dominant idea in biology, and much later still in physics.

It was Spencer, rather than Darwin, who popularized the word evolution, even before the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species in 1859. In the first edition, Darwin scarcely used the word ‘evolution’; only in the sixth edition did he begin to apply it to his theory, and then only sparingly. Instead, he wrote of ‘descent with modification’ or simply ‘progress’.12

The word evolution literally means ‘unrolling’. It was originally used to refer to the progressive unfolding of embryonic structures such as buds. The ‘evolutionist’ school of eighteenth-century biology maintained that the development of embryos took place by the evolution of a microscopic preformed structure that was present in the fertilized egg in the first place.

Thus evolution implied a pre-existing plan or structure that progressively unrolled in time. This is probably why Darwin avoided this word when he first put forward his theory.13 The ‘evolution’ of life would imply the existence of a pre-existing structure or plan – presumably a divine plan – and this is what Darwin wanted to rule out. But if they were not divinely planned, how could the forms of life on Earth have evolved by spontaneous natural processes?

Darwin found an answer that mirrored processes at work in the progress of commerce and industry: innovation, competition, the elimination of the inefficient and the inheritance of wealth.

In the realm of life, Darwin pointed out, organisms vary spontaneously, offspring tend to inherit the characteristics of their parents, and in the competition that inevitably results from the prodigious fertility of plants and animals, the unfit are eliminated by natural selection. Thus natural selection could, he thought, account for both the wonderful adaptations to their environment shown by plants and animals and the progressive development of new forms of life.14 This conception was summarized in the title of his most famous book, The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.

Darwin’s theory was cast within the context of a mechanistic universe; his evolutionary tree of life grew up within a world of physical eternities. We now consider in more detail how this pre-evolutionary framework of thought has shaped the Darwinian theory of evolution. We then go on to consider the possibility of a new evolutionary synthesis – a synthesis in which the evolution of life can be understood as one aspect of a cosmic evolutionary process in which not just nature but the ‘laws of nature’ evolve.

Time for very slow change

An essential precondition for Darwin’s theory of progressive evolution by gradual change was the expansion of terrestrial time. The biblical account of creation was generally supposed to refer to events that occurred only thousands of years ago: according to one well-known chronology the world was created in 4004BC. The mechanistic cosmology provided a very different context for the origin of the Earth: a universe that went on forever.

Descartes, for instance, supposed that the planets were carried around the Sun in a vortex of transparent aether (above), and saw no reason why one vortex should not run down while another appeared elsewhere. In this way a sun and planetary system, such as ours, could be formed within the ceaseless motions of the physical universe. Or, according to other theories, the Earth had been a comet, formed by the condensation of dust particles in space under the influence of gravity into a solid body, which had then been trapped in orbit around the Sun. Or the Earth had been formed by the cooling of hot matter thrown out by the Sun when a comet dived into it.15

The philosopher Immanuel Kant proposed the most successful theory in 1755. According to his ‘nebular hypothesis’ the solar system began as a cloud of dust particles that condensed under the force of its own gravity and gradually acquired a tendency to rotate. Small amounts condensed into solid bodies circling around the main concentration, which ignited to form the Sun. In Laplace’s System of the World (1796) it was assumed that all stars condensed in this way; hence the majority had planets circling them. The gradual formation of a planetary system such as ours therefore became a perfectly natural, mechanistic phenomenon. There was no need for God to have created the Earth, or the Sun, or indeed anything at all.

Such theories provided one background for speculations about the history of the Earth. The book of Genesis provided the other: the Earth and the living creatures on it were created in stages, represented by the days of creation. After the creation, there had been a series of catastrophes on Earth, most notably the Flood.

Throughout the long history of evolutionary debate, these two models have continued to conflict and to interact with each other. Mechanists have generally preferred slow, gradual change; those who have believed in the divine guidance of evolution have generally seen in it a series of stages and sudden jumps. Of course, abrupt changes do not necessarily imply divine intervention, but with the Bible in the background, they have often been thought to do so.

As the science of geology developed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, some geologists saw evidence in the rock strata for processes not unlike those described in the book of Genesis: clear evidence for a flood or a series of floods; sudden discontinuities; and in the strata above the primary rocks, the occurrence of fossils roughly in the order of Genesis – fish, animals on land, and finally man.16

Others, in the light of the physical eternity of the world machine, tried to find a conception of the Earth that was as gradual and as non-progressive as possible. At the end of the eighteenth century, James Hutton insisted that the scientific geologist should do his utmost to explain the structure of the Earth through causes he can observe in action now: ‘We find no vestige of a beginning, no prospect of an end.’ He dismissed as unscientific the idea of catastrophes on a scale we no longer observe. We see landmasses continually eroded by wind and water; the debris is carried out to sea and deposited on the ocean floor, where it can harden into rock strata; earthquakes can elevate these new rocks to form dry land. Earthquakes are driven by heat and pressure from the Earth’s core, and volcanoes occur when molten rock from the interior finds its way to the surface.17

Because the changes we observe today are very slow, Hutton’s scheme demanded a great antiquity for the Earth, an innovation of the greatest importance.18

Charles Lyell took this gradual approach further in his Principles of Geology (1830–33), which strongly influenced Darwin. Like Hutton, Lyell adopted a steady-state view of the Earth and emphasized the role of gradual changes in accordance with universal physical laws. He denied any directional trend in the development of life. He tried to account for the fossil evidence in terms of fluctuating climates, and supposed that all life forms had always been present in every geological period; there had been no sequential development of higher forms from lower – except for the appearance of man.19

However, the investigations of rock strata by geologists increasingly supported the idea of directional changes in the Earth’s development. Sudden breaks between rock formations indicated sudden changes in conditions. Most spectacular of all were the remains of giant reptiles such as dinosaurs. The sequence of fossil remains convinced many naturalists that the history of animal life began with an age of invertebrates, followed by fishes, reptiles, mammals and finally man.

Some theologians saw in this process the creative guidance of God. New species did not appear gradually through the operation of everyday laws of nature; they appeared suddenly through divine interventions in the history of life. Periodic extinctions occurred as a result of catastrophes, and then new forms of life were created.20

Darwin rejected divine intervention by insisting that evolution took place gradually through the smooth operation of the ordinary laws of nature: there were no sudden changes. This aspect of his theory was controversial from the outset, but Darwin stuck to the principle of gradual evolution in the face of all criticism. To admit the existence of any abrupt and inexplicable changes would, he believed, be ‘to enter into the realm of miracle, and to leave those of science’.21

In the sixth edition of The Origin of Species, Darwin did make one concession to his critics:

One class of facts, however, namely the sudden appearance of man and distinct forms of life in our geological formations, supports at first sight this belief in abrupt development. But the value of this evidence depends entirely on the perfection of the geological record, in relation to periods remote in the history of the world. If the record is as fragmentary as many geologists strenuously assert, there is nothing strange in new forms appearing as if suddenly developed.22

This argument has a familiar ring, and is still in widespread use today. Darwinians have generally followed Darwin in emphasizing the role of gradual change, and the absence of evidence for missing links has always been explained in terms of imperfections in the fossil record. But the evidence for catastrophes and the abrupt appearance of new forms of life has not gone away. On the contrary, it has been strengthened by increasingly detailed studies of the fossil record. Evolution that occurs by fits and starts seems to fit the facts better than a process of slow and steady change, and the former idea has been advanced again and again. Its most recent form is the hypothesis of ‘punctuated equilibria’.23

Meanwhile, the notion of global catastrophes has undergone a revival in scientifically respectable form. In 1980, abnormal quantities of iridium and other metals were found in clay layers at the boundary between Cretaceous and Tertiary rock strata – in other words layers which were formed some 65 million years ago, at the time that the dinosaurs, as well as many other animals and plants, became extinct. Many scientists now accept the hypothesis that an asteroid collided with the Earth and caused so much dust to be thrown into the atmosphere that sunlight was blotted out for weeks, causing the extinction of dinosaurs and many other forms of life.24 This hypothesis gained in plausibility as a result of calculations of the effects of a nuclear war, and in particular the prospect of a ‘nuclear winter’ caused by the blotting out of sunlight by the smoke and debris in the atmosphere.25

Subsequently, a variety of calculations have suggested that mass extinctions occurred over the last 250 million years with a periodicity of about 26 million years. The regularity of this cycle suggests the need for an astronomical explanation, and several have been proposed. We find ourselves back in the realm of great cycles of astronomical time.

One proposed explanation is that the Sun has a dark companion star, Nemesis, in a highly eccentric orbit. When Nemesis comes close to the comet cloud at the outer limits of the solar system, it disturbs it, triggering an intense shower of comets. The ensuing series of impacts on the Earth lasts up to a million years. Another model proposes a cycle due to the Sun’s oscillation about the plane of the galaxy, resulting in changes in cosmic radiation sufficient to cause major climatic changes. Yet another proposes that the Earth may have passed periodically through interstellar clouds of dust or gas.26 But some scientists argue that the great extinctions have followed no such regular cycle after all.27 The debate continues.

The tree of life

In the beginning, according to the book of Genesis:

The Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden … And out of the ground made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden.28

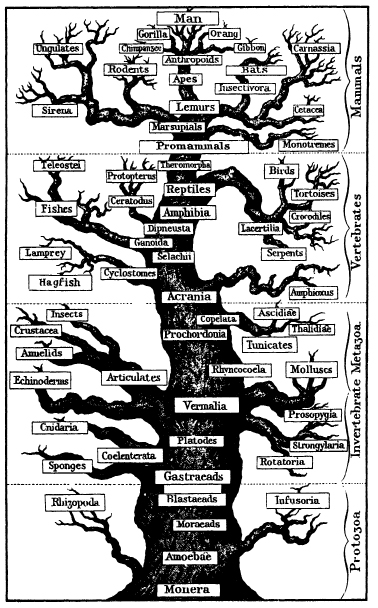

In Darwin’s great evolutionary vision, the whole of life developed like a great tree: the evolutionary tree of life (Fig. 3.1). Ever since the first seed of life appeared on Earth, this tree had been growing by itself, entirely naturally and in accordance with the laws of the natural world. Evolution, like the growth of a tree, was an organic, spontaneous process of continual growth and adaptation to the prevailing conditions of life. It all happened naturally.

Figure 3.1 The evolutionary tree of life, according to Ernst Haeckel. (From Haeckel, 1910)

For Darwin, it was not God who planted the tree of life, nor God who tended it: Darwin conceived of God very differently. God was the designer and creator of the world machine, who had designed all living things within it in the most wonderful and intricate of ways. All creatures but man were inanimate; they were machines whose designing intelligence was outside themselves, in the mind of God, just as the designing intelligence of man-made machines is not inside the matter of the machines, but outside them, in their human makers.

One of the exponents of this kind of theology was William Paley. His Natural Theology (which deeply influenced Darwin in his youth) takes the beautiful and appropriate designs of living organisms as proof of a designing intelligence, and hence as proof for the existence of God. This book begins with his famous example of the watch. Suppose, he wrote, when walking on a heath I find a watch. Without knowing how it came to be there, its precision and intricacy of design would force us to conclude

that the watch must have had a maker: that there must have existed, at some time, and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers, who formed it for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction and designed its use.

He then extended this argument by analogy to the works of nature:

Every indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater or more, and that in a degree which exceeds all computation.

Paley compared the human eye to a man-made instrument such as a telescope, and concluded that ‘there is precisely the same proof that the eye was made for vision, as there is that the telescope was made for assisting it’.29

In a mechanistic universe designed by such a God, there was no freedom or spontaneity anywhere in nature. Everything had already been perfectly designed. For Darwin’s tree of life to grow of its own accord, Darwin had to get rid of this all-designing God. But he could do so only by finding some other way of explaining the designs and purposive adaptations of flowers, wings, eyes – indeed of everything alive. He, like Paley, found this designing agency outside living organisms – but it was not in God, it was in nature. Natural selection chose the best designs from those which Nature herself threw up spontaneously. And, working gradually over many generations, natural selection shaped all the forms of life there are, and all the forms that have ever existed.

Darwin started from the analogy of human selection whose powers can be seen so clearly in the great range of varieties of dogs, pigeons and other domesticated animals and plants. All these had been produced through spontaneous variation and by selective breeding, through conscious or unconscious human selection. Natural selection worked in a similar way, except that no consciousness and no purposes were involved. The term ‘natural selection’ could, he admitted, be taken to imply some conscious choice, but this was not what he meant. Nor was natural selection an active power:

It has been said that I speak of natural selection as an active power or Deity: but who objects to an author speaking of the attraction of gravity as ruling the movements of the planets? Everyone knows what is meant by such metaphorical expressions; and they are almost necessary for brevity … With a little familiarity such superficial objections will be forgotten.30

And thus Darwin replaced the designing intelligence of Paley’s machine-making God with the blind workings of natural selection. Darwinians have continued to do so ever since.

The blind watchmaker

Richard Dawkins, one of the most forceful modern defenders of Darwinism, replied to Paley all over again in his book The Blind Watchmaker (1986). Dawkins opened with a statement of faith:

This book is written in the conviction that our own existence once presented the greatest of all mysteries, but that it is a mystery no longer because it is solved. Darwin and Wallace solved it, though we shall continue to add footnotes to their solution for a while yet … I want to persuade the reader, not just that the Darwinian world view happens to be true, but that it is the only known theory that could, in principle, solve the mystery of existence.31

Dawkins’ argument, like Darwin’s, stands in antithesis to Paley’s. And Paley’s arguments have been resurrected in a modern, molecular biological form by the advocates of Intelligent Design.32 But notice that both sides of this debate share an assumption that is not questioned by either: the mechanistic worldview. Plants and animals are like machines; either they are intelligently designed by an external intelligence, or they are the product of the blind workings of evolution by natural selection. But what if we change our way of thinking about the external designing intelligence, or about the nature of life? Different possibilities open up that do not fit into either of these standard positions. Here are two examples: the first involves a modified conception of external designing intelligence, and the second the idea of creative organizing principles within life itself.

Alfred Russel Wallace, like Darwin, understood the power of natural selection; he, like Darwin, discovered it. But he became convinced that Darwinian mechanisms alone could not explain the evolution of life. His last book was called The World of Life: A Manifestation of Creative Power, Directive Mind and Ultimate Purpose (1911). In it he proposed that ‘higher intelligences’ had directed the main lines of evolutionary development in accordance with conscious purposes:

We are led, therefore, to postulate a body of what we may term organizing spirits, who would be charged with the duty of so influencing the myriads of cell-souls as to carry out their part of the work with accuracy and certainty … At successive stages of development of the life-world, more and perhaps higher intelligences might be required to direct the main lines of variation in definite directions in accordance with the general design to be worked out … Some such conception as this – of delegated powers to beings of a very high, and to others of a very low grade of life and intellect – seems to me less grossly improbable than that the infinite Deity not only designed the whole of the cosmos, but that He Himself alone is the consciously acting power in every cell of every living thing that is or ever has been upon the earth.33

By contrast, Henri Bergson saw the purposive organizing principles of the evolutionary process as internal to the evolving forms of life. He compared the evolutionary process to the development of mind through the onward movement of the current of life, the élan vital:

This current of life, traversing the bodies it has organized one after another, passing from generation to generation, has become divided among species and distributed amongst individuals without losing any of its force, rather intensifying in proportion to its advance … Now, the more we fix our attention on this continuity of life, the more we see that organic evolution resembles the evolution of a consciousness, in which the past presses against the present and causes the upspringing of a new form of consciousness, incommensurable with its antecedents.34

Bergson did not, however, believe that this process of creative evolution had any ultimate, external purpose. If there was a God of the evolutionary process, he was not an external God, but a god who created himself in the very process of evolution.

The evolutionary theories of Wallace and Bergson illustrate what sorts of things can happen if we step outside the Paley-Darwin antithesis. But when we step back into the mechanistic worldview, the choice narrows again to that between the designing intelligence of the Great Artificer, or the blind inanimate mechanisms of Darwinian evolution.

But why should we keep forcing living organisms into mechanistic metaphors? Why should we not think of them as they really are: living organisms?

Evolving organisms

For over 80 years, an alternative to the mechanistic philosophy of nature has gradually been developing: the philosophy of organism. This philosophy, sometimes called the holistic or organismic philosophy, or the ‘systems’ approach, is in one sense a new form of animism: nature is once again seen as alive, and all organisms within it contain their own organizing principles within themselves. These are no longer thought of as souls, as they are in the Aristotelian philosophy, but are given a variety of other names such as ‘systems properties’ or ‘emergent principles of organization’ or ‘patterns which connect’ or ‘organizing fields’. But the modern philosophy of organism differs in two essential respects from pre-mechanistic animism: first, it is post-mechanistic, and is developing in the light of the insights and discoveries of mechanistic science; and second, it is evolutionary.

As the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead pointed out in 1925:

A thoroughgoing evolutionary philosophy is inconsistent with materialism. The aboriginal stuff, or material, from which a materialistic philosophy starts is incapable of evolution. This material is itself the ultimate substance. Evolution, on the materialistic theory, is reduced to the role of being another word for the description of changes of the external relations between portions of matter. There is nothing to evolve, because one set of external relations is as good as any other set of external relations. There can merely be change, purposeless and unprogressive. But the whole point of the modern doctrine is the evolution of the complex organisms from antecedent states of less complex organisms. The doctrine thus cries aloud for a conception of organism as fundamental for nature.35

In Whitehead’s phrase, organisms are ‘structures of activity’ at all levels of complexity. Even subatomic particles, atoms, molecules and crystals are organisms, and hence in some sense alive.

From the organismic point of view, life is not something that has emerged from dead matter, and that needs to be explained in terms of the added vital factors of vitalism. All nature is alive. The organizing principles of living organisms are different in degree but not different in kind from the organizing principles of molecules or of societies or of galaxies. ‘Biology is the study of the larger organisms, whereas physics is the study of the smaller organisms,’ as Whitehead put it.36 And in the light of the new cosmology, physics is also the study of the all-embracing cosmic organism, and of the galactic, stellar and planetary organisms that have come into being within it. As the philosopher Lancelot Law Whyte put it:

The universe confronts us with this obvious but far-reaching fact. It is not a mere confusion, but is arranged in units which attract our attention, larger and smaller units in a series of discrete ‘levels’, which for precision we call a hierarchy of wholes and parts. The first fact about the natural universe is its organization as a system of systems from larger to smaller, and so also is every individual organism!37

Think, for example of a termite colony, which is an organism made up of individual insects, which are organisms made up of organs, made up of tissues, made up of cells, made up of organized subcellular systems, made up of molecules, made up of atoms, made up of electrons and nuclei, made up of nuclear particles. At each level are organized wholes, which are made up of parts that are themselves organized wholes. And at each level the whole is more than the sum of its parts; it has an irreducible integrity.

What are these elusive principles of organization that are manifested in organisms or systems at all levels of complexity? In L.L. Whyte’s words:

A neglected principle of order, or better, a process of ordering runs through all levels; the universe displays a tendency towards order, which I have called morphic; in the viable organism this morphic tendency becomes the tendency to organic co-ordination (not yet understood), and in the healthy human mind it becomes the search for unity which gives rise to religion, art, philosophy and the sciences.38

In an evolutionary universe, the organizing principles of all systems at all levels of complexity must have evolved – the organizing principles of gold atoms, for example, or of bacterial cells, or of flocks of geese, have all come into being in time. None of them was there in the first place, at the time of the Big Bang.

But were they already present as transcendent Platonic archetypes in an immaterial form, as it were awaiting the moment when they would first be manifested in the physical universe? Or are they more like habits that have developed in time?

These are the questions we explore in the following chapters of this book. We begin by considering the structures of molecules, crystals, plants and animals and the ways in which they come into being.

The whole of this book represents an attempt to develop a new conception of the evolutionary nature of things. In the final three chapters we return to a discussion of evolution, and conclude with a discussion of the nature of evolutionary creativity, leaving open the perennial question of whether or not the evolutionary process has any ultimate purpose.