1

Explaining Major Change in Military Strategy

Any explanation of why a state pursues a major change in its military strategy must address two questions. First, what factors prompt, spark, or trigger a state to change its strategy? Second, by what mechanism is the new strategy adopted? This chapter seeks to provide answers to these questions and then discuss how they will be used to examine changes in China’s military strategy since 1949.

In extending existing arguments that highlight the role of external sources of military change, one likely motivation for why states pursue a change in their military strategy has been overlooked. This motivation is a significant shift in the conduct of warfare in the international system, as revealed in the most recent war involving a great power or its clients. A shift in the conduct of warfare should create a powerful incentive for a state to adopt a new military strategy if it highlights a gap between the state’s current capabilities and the expected requirements of future wars it may have to fight.

The mechanism by which a new strategy is adopted depends on the structure of civil-military relations within the state. The structure of civil-military relations shapes whether civilian or military elites are more likely to be empowered to initiate a change in strategy. In socialist states with party-armies and not national ones, the party can grant substantial autonomy for the management of military affairs to senior military officers, who should be more likely to initiate a change in strategy than civilian party leaders. Such delegation, however, only occurs when the party’s political leadership is united around the structure of authority and basic policies.

This chapter unfolds as follows. The first section describes what is being explained (military strategy) and the type of change being explored (major

change in military strategy). The second section considers competing motivations that can explain when and why states pursue major changes in military strategy, focusing on significant shifts in the conduct of warfare. The third section examines the mechanisms by which military change can occur, emphasizing the structure of civil-military relations and how party unity in socialist states empowers senior military officers to initiate a change in strategy. The fourth and final section discusses the study’s research design, including methods of inference and measurement of these variables, and how these will be applied in the study of China’s military strategy since 1949.

Major Change in Military Strategy

National military strategy is the set of ideas that a military organization holds for fighting future wars. Military strategy is part of but distinct from a state’s grand strategy.

1

Sometimes described as high-level military doctrine, a state’s military strategy explains or outlines how its armed forces will be employed to achieve military objectives that advance the state’s political goals. Strategy is what connects means with ends by describing which forces are necessary and the way in which they will be used. Strategy then shapes all aspects of force development, including operational doctrine, force structure, and training.

2

National military strategy refers to the strategy for the use of a state’s military as a whole. Locating the level of analysis at the national level is important for several reasons. First, it facilitates comparisons with the process of strategic change in other armed forces by specifying the type of change being examined. Second, it identifies the relevant explanations and arguments from the literature on military doctrine and innovation. A healthy portion of this literature, for example, examines changes within military organizations, especially combat arms and the development of weapons systems. Explanations of these changes often invoke competition within or among the service branches, which might be less salient when examining change in a state’s national military strategy.

3

National military strategy can be analyzed across various dimensions. These include the offensive or defensive content of the strategy or the integration of the strategy with a state’s broader grand strategy, among others.

4

This study, however, seeks to explain why and when states decide to adopt a new military strategy that requires substantial organizational change. Although the offensive or defensive content of a strategy can impact stability in the international system, it does not necessarily capture much of what occurs in military organizations, such as changes in concepts of operations, operational doctrine, force structure, and training. In addition, especially after the nuclear revolution and the decline in wars of conquest, many national military strategies combine offensive and defensive operations in the pursuit of limited aims.

Characterizing these strategies as either offensive or defensive is problematic. Similarly, states may have multiple military objectives, some of which require defensive capabilities and others offensive ones. A state may also believe it needs to develop some offensive capabilities for defensive goals. How to categorize a state that plans to use force differently in diverse contingencies presents a challenge for scholars.

Military strategy is associated more broadly with the idea of doctrine. This book, however, is not framed around the concept of doctrine for several reasons. To start, scholars have offered a variety of definitions, which implies a range of different concepts and dependent variables.

5

In addition, a gap exists between how scholars tend to use the term and how military professionals and practitioners conceive of doctrine. Although scholars often use doctrine to refer to the principles of strategic-level activities by a military or a state, many modern militaries use doctrine to refer to the principles or rules that govern any type of activity, at any level, that a military organization conducts, especially operational and tactical activities.

6

Finally, the meaning of the word itself varies from military to military, which can complicate comparative studies. Although widely used within the US military at the tactical level, it was a grand strategic concept for the Soviet Union and is not used at all by the Chinese military.

7

Major change occurs when the adoption of a new military strategy drives a military organization to alter how it prepares to conduct operations and wage war. Major change requires that a military develop capabilities that it does not already possess to perform activities that it cannot currently undertake. This distinguishes major change from a minor change or an incremental adaptation in strategy, whereby an existing strategy is tweaked or refined but does not require substantial organizational change.

My definition of major change draws on the concept of military reform. According to Suzanne Nielsen, in a military context “reform is an improvement in or the creation of a significant new program or policy that is intended to correct an identified deficiency.”

8

Reform does not necessarily require that an organization successfully change how it performs all its core tasks. Nevertheless, if the reforms are successful and deficiencies are addressed, they can substantially improve organizational performance. Nielsen notes that major peacetime components of military reform include not just doctrinal change, but also changes to training practices, personnel policies, organization, and equipment.

9

The concept of reform captures a great deal of what military organizations do, especially in peacetime.

Major change in military strategy contains two components linked with military reforms and can be regarded as high-level military reform. The first is that the strategy articulates a new vision of warfare and a call for change in how a military prepares to fight in the future. The second is that the new strategy must require some degree of organizational change from past practices,

including operational doctrine, force structure, and training. Major change highlights the desire to pursue significant organizational reforms over their successful institutionalization. The reasons why a state might decide to adopt a new military strategy are likely to differ from those that explain successful reform within a military organization. Nevertheless, by identifying attempts at organizational reform, major change is much more than just the articulation of an abstract vision of future wars.

Major change is closely associated with the concept of innovation. However, they are different in one important respect. Although many scholars use innovation as another word for change, others define innovation in military organizations as a change that is unprecedented or revolutionary, a significant departure from past practice, and a change that has been successfully institutionalized or implemented within a military organization, usually to improve its effectiveness.

10

In other words, innovation is institutionalized change. Nevertheless, the concept of innovation as institutionalized change may be less helpful for understanding national military strategy because successful institutionalization is likely to be a matter of degree and a continuous process.

11

In addition, as noted, the factors that prompt or trigger a desire to change strategy may not be the same as those that explain its successful institutionalization within a particular organization.

Two final clarifications are necessary before proceeding. One clarification is that major change in military strategy must be distinguished from two other outcomes. The first is no change in military strategy. The second is a minor change in military strategy, defined as adjusting or refining an existing strategy. Here, although a state adopts a new national military strategy, the purpose of the change is to better accomplish the vision contained in the existing strategy.

Another clarification is that I focus on peacetime change in military strategy. This serves to distinguish it from wartime change.

12

It is important to note, however, that the concept of peacetime includes wide variation in the international threat environment. It only excludes military strategies that are devised in wartime for a particular conflict.

Motivations for Major Change in Military Strategy

Within the literature on military doctrine and innovation, a rough consensus exists around the primacy of external motivations for great powers to pursue change in military strategy. As these states develop armed forces to defend against external threats or project power over others, a focus on external factors is unsurprising. These existing external incentives for change should be viewed as forming a general model of external sources of military change. The caveat, however, is that scope conditions, some of which are more restrictive than others,

can limit the effect of these incentives in particular cases, and not all of them may apply to China’s past strategies.

The first motivation is an immediate or pressing external security threat. If a state’s current military strategy is ill suited to meet the threat that it faces, then it will seek to change its strategy. One source of immediate threats can arise through a change in a state’s security environment, such as an increase in the capabilities of an opponent or the appearance of a new adversary with a different set of capabilities. Another source can be created by the failure of a state’s military to perform as expected during its most recent conflict, especially if it was defeated on the battlefield or failed to achieve its military objectives. Defeat or failure suggests a vulnerability or weakness to be rectified through the adoption of a new military strategy, though defeat could also lead a state to enhance the implementation of its current strategy.

13

The effects of immediate and pressing threats apply to all states and are not limited by many scope conditions—only a gap between the existing strategy and the new threat.

A second motivation for change in strategy, closely related to immediate threats, is assessments of an opponent’s military strategy. A military may adopt a new strategy in response to a change in the war plans of its adversary. In a study of Soviet military doctrine, Kimberly Marten Zisk describes this as a “reactive innovation,” even in the absence of an immediate threat.

14

The possibility of a reactive innovation is limited to states already in a strategic or an enduring rivalry that would face a greater threat if an adversary changes its strategy.

15

Rivals must closely monitor the war plans and capabilities of their opponents and change their own strategy as circumstances require. Zisk, for example, argues that Soviet doctrine changed in response to changes in American grand strategy and military doctrine. Following the US adoption of “Flexible Response” that increased the role of conventional forces in the defense of Western Europe, for example, Soviet doctrine shifted to emphasizing limited war and the “conventional option.”

16

A third motivation for major change is the creation of new missions and objectives for the military by the state. This source of change can be described as environmental because it occurs independently of any military strategy.

17

New missions can arise for a variety of reasons, such as the acquisition of new interests abroad to be defended, changes in the security needs of an ally, or shifts in a state’s political goals for the use of force that require new capabilities (such as a desire to reclaim lost territory or establish buffer zones). In the early twentieth century, for example, the acquisition of the Philippines after the Spanish-American War created new overseas interests for the United States that in turn altered its military strategy. By acquiring a colony in the Pacific, the United States needed to prepare to fight naval battles far from home, which highlighted the importance of amphibious warfare to seize naval

bases to support operations in the region.

18

Likewise, Adolf Hitler’s broad ambitions required a force capable of mobile offensive operations.

19

New missions can require a military to perform new types of operations, which in turn can require a new military strategy. The impetus for change, however, lies in a state’s broader international political environment.

20

New missions as a source of change may be especially relevant to rising powers, which acquire new interests to be defended as their capabilities expand.

The long-term implications for warfare of basic technological change provide a fourth external motivation for change in military strategy. The advent of new technologies may lead states to consider their implications for warfare and to adjust their military strategies accordingly. Here, a state does not face an immediate or pressing threat. Instead, it considers how today’s technological advances will impact tomorrow’s war. Stephen Rosen, for example, suggests that the invention of the airplane led to the development of aircraft carriers, which ultimately replaced battleships as the main platform of naval firepower.

21

This motivation for change, however, applies primarily to the most advanced states in the system that enjoy a relative abundance of resources for developing military power along with mature industrial and technological capabilities that can develop or apply these technologies to warfare.

22

These motivations can account for strategic change under different circumstances, but they remain incomplete. Specifically, they cannot account for why a state might change its military strategy when these motivations are absent, such as when the state is not facing an immediate and pressing threat. Another possible motivation for a change in strategy is a shift in the conduct of warfare in the international system, as revealed in the last war that involved one or more great powers or their clients (equipped with their patron’s weaponry).

23

Such wars are similar to what Michael Horowitz describes as a “demonstration point” in the context of discrete military innovations.

24

This motivation should be especially powerful if a gap is believed to exist between how a state’s military plans to wage war and the requirements of future warfare. Since 1945, for example, the 1973 Arab-Israeli War has attracted a great deal of attention from military professionals because of its implications for armored warfare and the importance of the operational level of war.

25

Likewise, the 1990–91 Gulf War demonstrated the potential of precision-guided munitions when paired with advanced command, control, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems.

26

Of course, not all states will draw the same lessons from the same conflict, as demonstration effects will be filtered by a state’s security environment, military capabilities, and resources.

27

Nevertheless, other people’s wars may demonstrate the importance or utility of existing practices as well as what some scholars call military revolutions or military innovations.

How does this argument differ from emulation? In

Theory of International Politics

, Kenneth Waltz argues that because international politics is “a

competitive realm,” states will copy and emulate the most successful military practices in the system. In particular, Waltz suggests, “contending states imitate the military innovations contrived by the country of the greatest capability and ingenuity,” including its weapons and strategies. Waltz’s argument includes both a potential motivation for change (competition) as well as a mechanism by which such change occurs (emulation, discussed in the next section). As a possible motivation for when and why states pursue change in military strategy, however, Waltz’s argument is underspecified. Although Waltz highlights competition as a reason for change in strategy, the specific motivation for change at any one time is unclear. As discussed above, much of the existing literature seeks to identify different motives that the competitive pressures of the international system create for changing strategy. Although competition under anarchy causes states to change their military strategies, the more interesting questions are when and why such change occurs, which can be answered only by looking beyond the general argument that Waltz offers.

Shifts in the conduct of warfare are one such incentive for a major change in military strategy. When a war occurs in the international system, states are likely to assess its key features and implications for their own security. Depending on their strategic circumstances, states may seek to emulate or to develop other responses, such as countermeasures. The 1999 Kosovo War was revealing not just because it highlighted advances in stealth and precision-strike capabilities, but also because it suggested that simple tactics and procedures such as camouflage could blunt the potentially devastating effects of precision-guided munitions.

28

States vulnerable to airstrikes might have focused on the latter and not the former. Waltz also suggests that emulation will most likely occur among peer competitors or “contending states.” Yet the lessons from contemporary conflicts should be especially relevant for developing countries or late military modernizers, such as China, that may not yet be peer competitors but that seek to strengthen their armed forces and must allocate their scarce resources for defense with care.

External motivations for change have received the most attention in the scholarly literature because the basic mission for most armed forces of great powers or aspiring great powers is to defend the state against external threats. Nevertheless, internal motivations are also possible triggers for a change in strategy. But the arguments about organizational biases and military culture reviewed briefly below are usually presented to explain stasis or the lack of change in a military organization. For this reason, they are not especially well suited to answering the question posed by this book about when and why China changes its military strategy.

The first internal motive for change is a military’s organizational bias or preference for offensive operations that increase its autonomy, prestige, or resources. The logic of this motive draws heavily on organization theory. Such

biases can only have an effect on strategy, however, when civilian control is weak or when a benign external environment limits civilian monitoring and allows organizational biases to influence strategy.

29

The second internal motive is a military’s organizational culture apart from an offensive bias. A military’s organizational culture can shape its preferences, including for the kinds of strategies it would prefer to adopt. In her examination of the role of organizational culture in the British and French militaries in the interwar period, Elizabeth Kier suggests that when the civilian government in France limited conscription to one year, the military adopted a defensive doctrine because it believed that such recruits would be unable to perform offensive operations required for a more robust defense.

30

More recently, in a detailed study of counterinsurgency operations, Austin Long demonstrates how the deep-rooted cultures of the US Army, US Marines, and British Army shaped how they conducted such operations, regardless of the formal or operational doctrine they adopted. The effect of organizational culture should be especially salient in operational environments where information is ambiguous.

31

Mechanisms of Major Change in Military Strategy

The second component of any explanation of strategic change is the mechanism by which change occurs, which shapes how a new military strategy is formulated and adopted. In the literature on military doctrine and innovation, much of the debate about how change occurs in military organizations revolves around whether civilian intervention is required or whether change can be led by military officers and occur autonomously. The answer depends on the structure of civil-military relations and whether or not it empowers military leaders. In socialist states like China, with party-armies and not national ones, the structure of civil-military relations empowers senior military officers to initiate changes in strategy under certain conditions—when the party is united and delegates responsibility for military affairs to the armed forces.

CIVILIAN INTERVENTION VERSUS MILITARY-LED CHANGE

Two of the most commonly discussed mechanisms of change in military organizations examine the relative roles of civilian and military elites. Some scholars suggest that major change requires civilian intervention, while others contend that senior military officers can lead such change autonomously and independently.

Civilian intervention as a mechanism for major change in military strategy is most commonly associated with either high threat environments or states with revisionist goals. Both conditions place a premium on the integration of a state’s grand strategy with its military strategy to ensure the security of the

state or the achievement of its ambitious political objectives.

32

Yet, deductively, no reason exists why other motivations for a change in strategy might not also occur through civilian intervention, except perhaps regarding the long-term military implications of basic technological change. Even here, though, efforts to develop new weapons systems would require funding controlled by civilians.

Civilian intervention for military change can be direct or indirect. In its direct manifestation, a civilian political leader pushes the military to change, such as Hitler’s intervention in the Wehrmacht before World War II.

33

In its indirect form, the structure and strength of civilian control mechanisms can create strong incentives for military officers to pursue the change that civilians desire. In a study of counterinsurgency doctrine, Deborah Avant demonstrates that the British military adapted to the counterinsurgency campaigns political leaders wanted to wage because civilian oversight and monitoring was centralized in the cabinet, which controlled military promotions. The US military was less able to adapt to such campaigns because the executive and legislative branches of government shared control of the armed forces, which allowed military elites to resist some civilian oversight.

34

Military-led change without civilian intervention is another possible mechanism of strategic change. This mechanism stresses military autonomy, positing that change can occur from within, led by senior military officers without a push from civilians.

35

In principle, senior officers could advocate for a change in strategy in response to any of the external motivations identified above. As some scholars have noted, military officers are perhaps more sensitive to changes in the conduct of warfare than civilians because officers must plan to confront these changes on the battlefield.

These two mechanisms—civilian intervention and military autonomy—are usually cast as opposing arguments. Most studies of military innovation begin by contrasting these approaches.

36

Nevertheless, these two mechanisms are probably much more complementary than commonly believed, depending on two scope conditions. The first is the urgency and intensity of external threats that a state faces. The more immediate and greater the threat, the more likely civilian leaders will monitor their military’s strategy and intervene if it is ill-equipped to meet the threat.

37

Conversely, the less immediate or intense the threat, the greater the likelihood that a change in strategy will come from within a military organization as it considers the requirements of its future security environment.

The second scope condition concerns the level of organizational change that one seeks to explain. Civilian intervention should be more likely to occur as one moves from the level of tactics and operations to the level of strategy, as information asymmetries decrease, and as formal channels of civilian influence over the armed forces grow. By contrast, military-led change should be more likely to occur as one moves within a military organization from the level of

strategy to the level of operations and tactics because of the importance of specialized technical knowledge that most civilians will lack.

National military strategy is perhaps the level of military affairs where civilian and military elites are equally positioned to shape the process of strategic change. Civilians must rely on the professional and technical expertise of the military to devise and implement a strategy, while the military depends on civilians for the necessary resources to implement a new strategy. If this is the case, then the structure of civil-military relations and the degree of delegation to the armed forces should play an important role in creating relatively greater opportunities for either civilians or senior military leaders to initiate a major change in military strategy.

Although the structure of civil-military relations can determine whether civilian or military elites are more likely to push for change in military strategy, scholarship on military innovation and civil-military relations is only loosely integrated. On the one hand, studies of civil-military relations rarely treat the subject as an independent variable that can explain military outcomes of interest, such as operational doctrine, effectiveness, or innovation.

38

Instead, most studies seek to explain the dynamics of civil-military relations and the potential for military intervention in the civilian sphere, such as coups, military influence in politics short of coups, civil-military conflict, military compliance with civilian demands, and the dynamics of civilian delegation.

39

Scholars have only just started to explore civil-military relations as a variable that can explain military as well as political outcomes, and it requires greater attention as both an intervening and independent variable in military affairs.

40

On the other hand, few studies of military innovation draw explicit links with civil-military relations. To be sure, civilian intervention is discussed, but usually not in the context of theoretical approaches to civil-military relations. For instance, many studies of World War I identify weak civilian control as a key source of the offensive biases displayed by militaries in the run-up to the conflict.

41

Similarly, although Avant casts her argument in terms of institutional theory, its logic is based on the incentives for military change created by different mechanisms of civilian control in democratic systems and how these mechanisms shape the responsiveness of the military to the preferences of civilians.

42

Likewise, in Kier’s study of French and British military doctrine in the interwar period, a key variable is the degree of consensus among civilian elites about the role of the armed forces in society. When consensus was absent, political elites sought to intervene more in military affairs.

43

Finally, the struggle for autonomy features prominently in Zisk’s study of Soviet military doctrine, but is never discussed in terms of research on Soviet civil-military relations or theories of civil-military relations more generally.

44

These examples are far from exhaustive. Instead, they illustrate how the structure

of civil-military relations in a given society creates opportunities for either civilian or military elites to intiate and lead the process of strategic change.

PARTY UNITY AND MILITARY CHANGE IN SOCIALIST STATES

In socialist states such as China, a distinct kind of civil-military relations suggests that senior military officers can be empowered to initiate change in military strategy without civilian intervention. Any discussion of civil-military relations almost always begins with Samuel Huntington’s arguments in

The Soldier and the State

.

45

Nevertheless, his framework fits somewhat uncomfortably with socialist states characterized by professional armies that are nevertheless subject to a series of intense political controls and routinely involved in activities beyond the military sphere, and which occasionally participate in internal party conflicts. Put simply, in terms of their relations with the civilian sphere, party-armies differ fundamentally from national armies. In socialist states, the more appropriate subject of study is not civil-military relations, but “party-military” relations.

46

Huntington starts with the premise that an inherent conflict exists between the state and its armed forces, where the greatest danger is military intervention into politics, especially coups. With party-armies in most socialist states, however, this problem does not exist: there have been few if any military-led coups in communist countries, especially those founded through violent revolution.

47

When the military does intervene in politics, it seeks to maintain the hegemony of the ruling communist party, not seize power for itself.

The effect of civil-military relations on the timing and process of strategic change in socialist states such as China reflects the structure of political authority in these societies. Building on various conceptualizations of civil-military relations in the Soviet Union, Amos Perlmutter and William Leogrande sought to develop a unified theory of civil-military relations in socialist states.

48

They explain that socialist states are characterized by the political hegemony of a “vanguard” party. This hegemony requires the subordination of all nonparty institutions, including the military, to the party and not to the state (which the party controls). Subordination of nonparty actors is achieved and sustained through a number of different mechanisms, including the creation of dual elites known as an “interlocking directorate” who hold top positions in the party and the military as well as the construction of a party structure of political commissars and party committees within the armed forces. Subordination of the military to the party, however, does not mean that the military lacks autonomy, especially in the realm of military affairs. The party must grant enough freedom to the military for it to perform the tasks that the party requires. As the technological complexity of war progresses, for example, militaries in socialist states

are likely to enjoy greater autonomy in military affairs in order to perform the tasks that are required.

49

From their analysis, Perlmutter and Leogrande draw several conclusions about civil-military relations in socialist states. First, conflicts over national policy are resolved within the party, not between the party and other institutions such as the state or military. Second, due to this institutional arrangement, the military’s participation in politics is the norm and not the exception as in noncommunist states. A party-army can be drawn into politics because a military officer with party membership, as William Odom writes, is an “agent of the party.” Third, when the military intervenes decisively in the political sphere, it does so to uphold and maintain the party and its hegemony over the state rather than to seize power. This applies even when the military intervenes to support one faction within the party over another. What prompts intervention is not the military’s desire for power, but disunity in the party that threatens its hegemonic position. A final implication that Perlmutter and Leogrande do not discuss is that the military may be required to defend the party not just against external threats to the state but also against internal threats to its continued hegemony. Thus, one should expect the military in socialist states to perform those tasks that the party deems necessary to its continued survival, including the suppression of dissent and opposition movements.

Perlmutter and Leogrande do not consider how party-military relations might influence military or strategic outcomes. Nevertheless, the structure of party-military relations should influence whether and when either party or military elites will push for change in military strategy in socialist states. Because the military in socialist states can enjoy substantial autonomy, it is positioned to initiate the process of strategic change. Yet because the military leaders are also party members, they will formulate new strategies consistent with the party’s broader political goals and priorities. As Odom notes, the military in socialist states is an “administrative arm” of the party, as are other state institutions, and “not something separate from and competing with it.”

50

If this view of party-military relations is accurate, the timing and process of strategic change in socialist states will depend on the unity of the party—the condition that enables substantial delegation of military affairs to senior military officers. Party unity refers to the agreement among the top party leaders on basic policy questions (i.e., the proverbial “party line” or general guideline) and the structure of power within the party. When the party is united, it will delegate responsibility for military affairs to the armed forces, with only minimal oversight. As a result, senior officers are likely to play a decisive role in initiating and formulating major changes in military strategy, if required by the state’s external security environment. When the party is united, the armed forces remain beholden to only one actor, the party, which sustains its autonomy in the military sphere to pursue strategic change. The party’s various control

mechanisms ensure that the military will adopt policies consistent with the party’s broader political objectives. Debate over military policy and strategy can occur, of course, but does so within the party. In this way, party unity creates an environment similar to Huntington’s ideal of objective civilian control, which fosters professionalism, even though a party-army is a politicized armed force. To borrow from Huntington, this might be described as “subjective objective control.”

51

The reasons why party unity enables strategic change in socialist states can be illustrated through Risa Brooks’s argument about strategic assessment. Brooks suggests that states are most likely to produce the “best” assessments when the preference divergence between civilian and military elites over questions of strategic assessment is low and when political dominance of the armed forces is high.

52

Party-military relations in many ways reflect such a relationship. As members of the same hegemonic socialist party, preference divergence between the top party leadership and senior military officers should be low. At the same time, a party-army is by definition under the political dominance of the communist party.

53

By contrast, disunity at the highest levels of the party will likely prevent major strategic change from occurring, even if the state faces strong external incentives for change. Disunity can paralyze strategic decision-making in a party-army for several reasons: first, the military may be required to perform nonmilitary tasks relating to governance or maintaining law and order.

54

If political disunity produces domestic instability (or vice versa), then the military may be given a new primary mission of restoring or maintaining law and order. Second, the military may become the object or focus of political contestation at the highest levels of the party. Because the military is the ultimate guarantor of the party’s hegemonic rule, contending groups or factions may seek to increase their influence over the military to prevail in the intraparty struggle. Factional struggle within the party may also spread to the armed forces, hampering their ability to focus on military affairs. Third, as a party-army, the military must also carry out the policies of the party, especially ideological ones such as mass campaigns. Such campaigns would likely interfere with military training and politicize larger policy decisions such as a change in strategy. Fourth, even if the military remained united and depoliticized during periods of disunity, the party may be unwilling to consider proposals for strategic change or, as with any major policy decision, a divided party might be unable to come to any agreement on military change. Fifth, top military leaders may also become involved in intraparty politics—again, at the expense of military affairs such as strategy.

Deductively, periods of party disunity could present the military with an opportunity to back one party faction or group in exchange for support from that faction for its own interests once unity is restored. For example, the military might demand a higher budget or approval of a new military strategy

in exchange for their support in order to end the period of disunity. Nevertheless, party-armies should be less able or less willing to engage in these kinds of bargains. Their intervention may not restore unity, and in fact could be a source of greater intraparty tension, further harming the military and the party. The military would be seen as an overt political actor and an independent source of power that could increase disunity and instability in the long term. Moreover, if disunity has created factionalism within the military, then it may be unable to act in a unitary fashion in the intraparty competition. Instead, the military, or a faction in the military, would most likely intervene not to advance its parochial organizational interests, but only to restore unity in the party.

A final question to consider is whether party unity is independent of the external motivations for change. For example, the onset of an immediate or pressing external threat could enhance party unity and thus party unity would be a function of the external environment. External threats are likely to enhance elite cohesion in democracies, as leaders are ultimately accountable to their publics and more likely to set aside partisan differences during periods of duress. Nevertheless, external threats may be less likely to unify a fractured Leninist party in a socialist state, where the party leadership is not accountable to the public and the issues that create disunity involve either the distribution of power within the party or questions relating to the party’s basic or fundamental policies. External threats are unlikely to compel leaders to resolve these differences. In the case of China, for example, growing tensions with the Soviet Union after 1969 did little to unify the party leadership that had been divided during the Cultural Revolution.

EMULATION OR DIFFUSION?

The main alternative set of mechanisms to the debate over civilian intervention are the processes of emulation and diffusion. When applied to a change in military strategy, arguments about emulation or diffusion both expect that it occurs because one state seeks to copy or imitate the strategy of another. The relative roles of civilian and military leaders are largely irrelevant, as emulation and diffusion assume elite consensus about the preferred course of action.

Emulation offers one mechanism through which a change in strategy might occur. This draws on the work of Kenneth Waltz, who argues that competition “in the arts and the instruments of force … produces a tendency toward the sameness of the competitors.” Waltz further claims that states should adopt the practices of the militarily most powerful states: “The weapons of the major contenders, and even their strategies, [will] begin to look much the same all over the world.”

55

Competition leads to copying and convergence.

56

Emulation is an especially important potential mechanism for developing countries or late military modernizers such as China. These states not only have the desire

to increase their military capabilities, but will also likely search for templates or models to import in order to jump-start their modernization drive.

57

Although the competitive pressures of the international system no doubt may lead states to adopt new military strategies, emulation as a mechanism for major change in strategy has several limitations (with the caveat that Waltz only devoted two paragraphs to the subject).

58

One limitation is that its logic implies that because states will imitate leading practices, they must face the same set of strategic circumstances and intend to fight the same type of war (most likely industrialized wars of conquest among peer or near-peer great power competitors). Of course, states face a variety of strategic circumstances, and security maximization might be best achieved through countermeasures or counterinnovations, or simply a different strategy, not necessarily by imitating and copying others.

59

A second limitation is that even if some institutional or organizational similarity among militaries occurs, this may be less helpful in illuminating the choices that states make about their military strategies. Since 1918, most states have moved to adopt elements of what Stephen Biddle calls the “modern system,” defined as a set of methods for conducting military operations “in the face of radical firepower.”

60

Earlier, as a precursor to the modern system, many states instituted the mass army.

61

In this sense, imitation might explain the choices that states make at the highest level of institutional design and that may be especially relevant during the formation of the modern state and the industrialization of warfare. At the same time, it cannot explain, for example, how a state intends to implement the modern system on the battlefield.

62

Waltz expects military strategies to converge, but this might be precisely where they should diverge because of the different goals, circumstances, and capabilities of states. Perhaps for this reason, Joao Resende-Santos explicitly excludes military strategy in a lengthy study of emulation.

63

Finally, at the most general level of institutional and organizational forms, what states seem to do is selectively adopt military practices (or innovations) developed by other states. This, in fact, would not be emulation if such selective adoption occurred because of a state’s particular threat environment, its resource endowments and capacity to mobilize resources, the level of its own military modernization, or its level of industrialization. States will not engage in wholesale emulation if it breaks the bank. Moreover, it may just not always be practical, given the long lead times for importing innovations from elsewhere. Instead, states will look for the most efficient solution to their security problem. Even if the style of warfare is similar to the modern system, national strategy will still determine how it is employed and for what ends.

The closely related literature on the diffusion of military innovations seeks to understand in more detail when and how the processes of emulation and imitation occur. Although similar, this work differs from Waltz’s argument

about emulation in several ways. First, it examines the variation in the adoption of military innovations, especially technological innovations such as the development of new weapons systems, as part of a broader effort to understand how the spread of military technology may influence the distribution of power in the system. Second, it typically examines discrete innovations, such as aircraft carriers or nuclear weapons. Third, it moves beyond structural factors to examine variables that might shape the choices of individual states, including those factors that push states to adopt foreign practices as well as those factors, especially cultural ones, that inhibit adoption. The range of potential factors includes geography, financial resources, access to military hardware necessary for the adoption of new operational doctrines or software, the social environment, national culture, organizational capital, organizational culture, and bureaucratic politics.

64

Like emulation, arguments about diffusion have a teleological quality, a sense that the adoption of military innovations, especially technical ones, is inevitable and will occur when constraints are few and when resources are abundant. The baseline expectation is that states will copy innovations if they have the means and ability to do so. Adoption does not occur when barriers to importation are present, such as culture, the lack of resources, or domestic politics. In one recent study of diffusion, for example, Michael Horowtiz argues that states are much more likely to adopt “major military innovations” when they possess the financial resources to fund development of these technologies and the organizational capital to develop them indigenously. What is missing from many accounts of diffusion, however, is a consideration of a state’s assessment of its security environment and its strategic goals, which in turn identify the capabilities required to defend the state and preferences for the adoption of military innovations. States facing different adversaries and pursuing different goals will likely make different choices about how to structure their armed forces and which foreign practices and innovations to adopt.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

To sum up, whether China pursues a major change in military strategy depends on whether it encounters a strong external incentive for change and whether politics within the party enables senior military officers to respond to these changes by formulating a new military strategy if necessary. The external stimulus—the shift in the conduct of warfare—is a necessary condition for major change to occur. Party unity is a sufficient condition that allows the military to respond to the external stimulus.

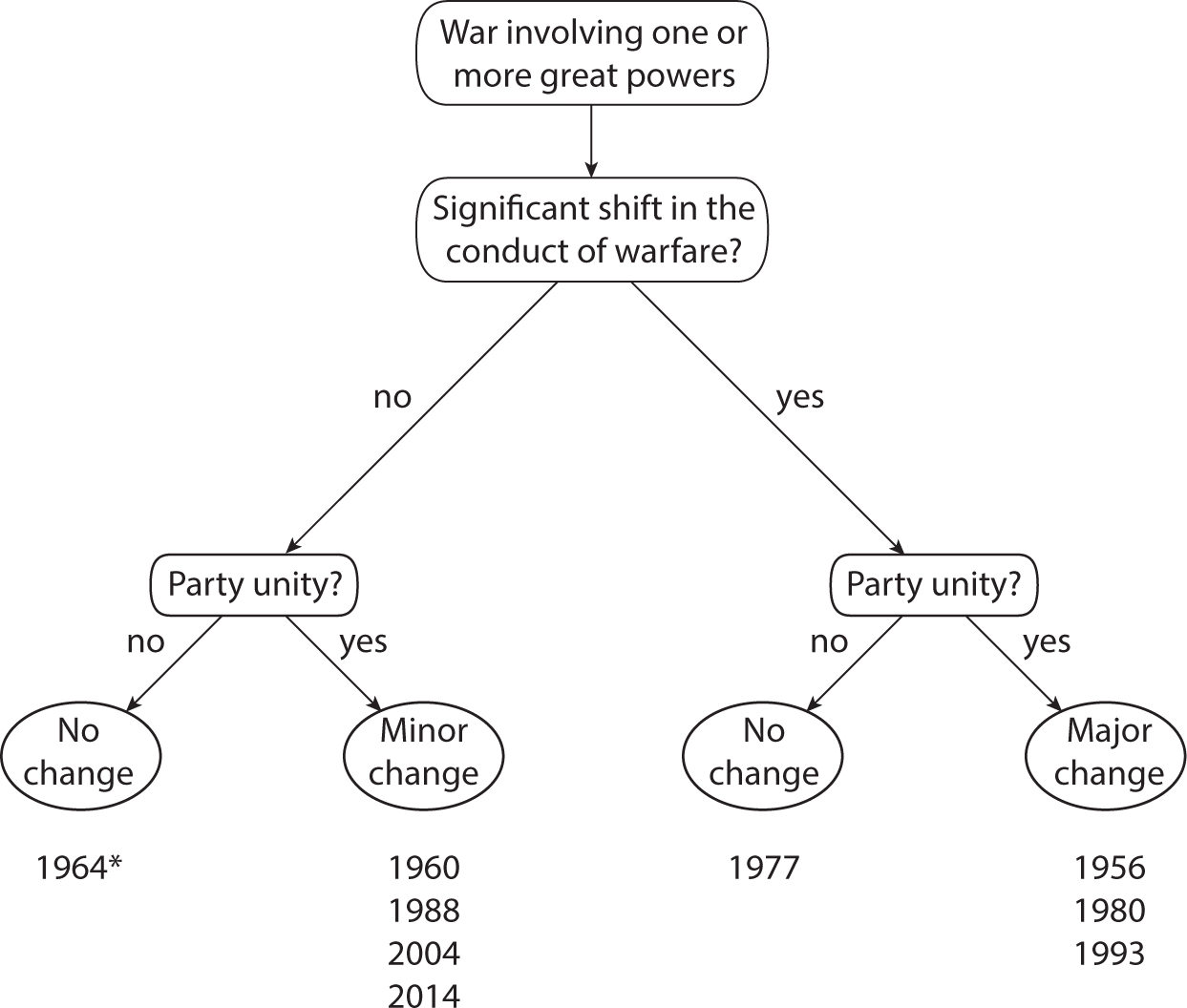

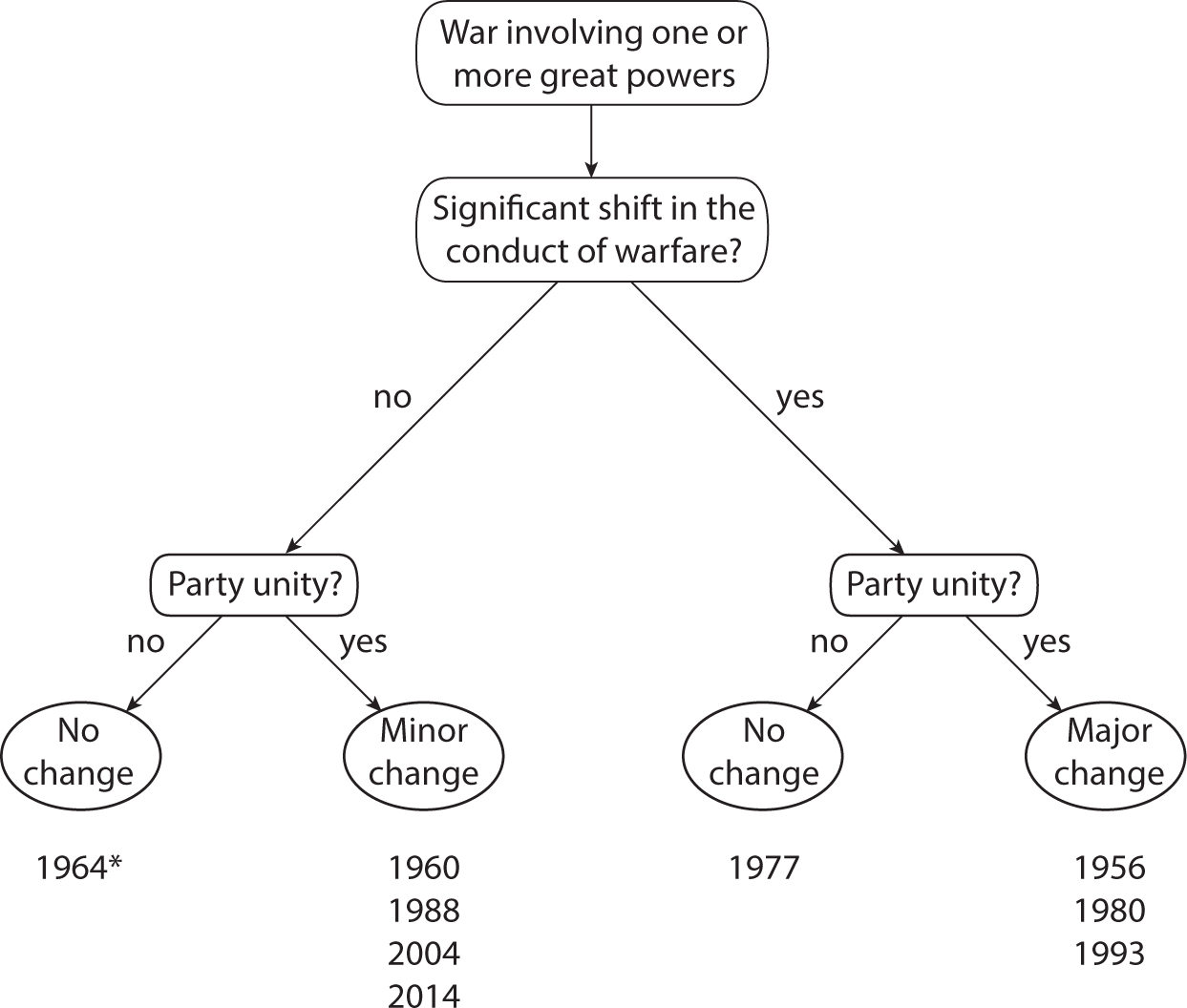

As shown in

figure 1.1

, four outcomes are possible. If China faces a shift in the conduct of warfare and the party is united, senior military officers will push for a major change in military strategy. If China faces a significant shift

in the conduct of warfare, but the party lacks unity, then no change in strategy will occur (major or minor), as disunity prevents the military from responding to the external stimulus. By contrast, if China does not face a significant shift in the conduct of warfare but the party is united, then senior military officers will pursue minor change in their country’s military strategy, if external circumstances require it. If China does not face a significant shift in the conduct of warfare and the party lacks unity, then party disunity will prevent the military from undertaking even minor changes in strategy.

FIGURE 1.1.

Conduct of warfare and party unity in strategic change

Note: The years below each node refer to my argument’s prediction for each of China’s strategic guidelines. The asterisk (*) denotes the adoption of a guideline not predicted by my argument.

This framework can accommodate all external motivations that could prompt a change in military strategy. This book argues that past changes in China’s strategy have occurred in response to assessments of a shift in the conduct of warfare. Looking forward, however, China may pursue a major change in its strategy in response to other external factors, such as new missions for its armed forces created by the expansion of its interests overseas. Depending on the intensity of these interests, this process could result in a major change in China’s military strategy, so long as the party remains united. Nevertheless, since 1949, a significant shift in the conduct of warfare best explains the

reasons why China’s senior military officers have pursued major changes in their country’s military strategy.

Research Design

Any explanation of major change in military strategy must complete two empirical tasks. The first is to identify those changes in military strategy that can be considered “major” and represent a clear departure from past strategy. The second task is to demonstrate why key decisions were taken at particular points in time and not others. Below I discuss how I will complete these tasks in the remainder of the book.

METHOD

This book uses two methods of inference. First, each of the three major changes in China’s military strategy is compared with the minor changes in strategy and periods of no change in strategy to determine which motivations and mechanisms best account for the major changes. Such comparisons are a variant of the method of “structured, focused comparisons.”

65

By examining both major changes as well as minor ones and periods of continuity, I explore the full range of variation in China’s military strategy, not just the instances of major change (which could bias the findings).

Second, the process by which change occurred is examined to determine which mechanism best accounts for change in military strategy. Examination of primary and secondary sources on military affairs, including official documents and leadership speeches, can help to determine if the decision to adopt a new strategy is consistent with the motivations for adopting a new strategy and if the change was initiated by senior military officers. Such process tracing permits an assessment of the mechanisms by which a change in strategy occurs.

66

The longitudinal study of change in one country’s military strategy over seven decades has several advantages. It controls for many potentially confounding factors, such as regime type, culture, and geography, while also allowing for wide variation in a state’s security challenges, threat environment, and wealth. It also permits a complete examination of the process of strategic change by focusing on just one country in detail, and allows scholars to examine periods when change was not pursued and when it might have been expected to occur over a seventy-year period.

This approach improves upon existing longitudinal studies of strategy in two ways. First, it restricts the analysis to the same type of change—the adoption of a new military strategy. This ensures unit homogeneity by holding constant the type of change being examined and the level within a military

organization where change should occur. Zisk’s study of Soviet doctrinal change, for example, compared both changes in grand strategy (the response to Flexible Response) and changes in operational doctrine (the response to AirLand Battle).

67

Second, by distinguishing among major, minor, and no changes in strategy, it allows for comparisons that reduce selection bias created by examining only instances of major change. This approach can isolate those factors linked with major change in strategy and not minor adaptations.

China presents a rich empirical environment for the study of change in military strategy. Many of the different potential motivations are present. To start, the intensity of threats that China faced since 1949 has varied widely. On one level, there have been several periods when China feared imminent attack, including the spring of 1962, when Taiwan mobilized forces; in 1969 after the clash with the Soviets over Zhenbao Island; and in the 1970s when the Soviets deployed hundreds of thousands of troops on its northern border. There have also been periods of sustained threats to Chinese security, such as during the Cold War, when China squared off against both superpowers, who changed their own military strategies in ways that might have prompted a reactive innovation. Likewise, China’s security environment has changed substantially over the past seventy years. Although homeland security and the defense of territorial claims have been the main missions assigned by the CCP to the PLA, these missions have begun to expand in the past two decades as China’s economy has grown. Regarding basic technology that might influence the conduct of warfare, China’s first military modernization began in the shadow of the revolution in firepower displayed during World War II and the birth of the nuclear revolution. The growing importance of information technology, and the “revolution in military affairs” it purportedly fosters, overlap with the last thirty years of the PLA’s modernization. Finally, a significant number of major wars with demonstration effects about the conduct of warfare have occurred over this period, from World War II to the 2003 Iraq War.

MILITARY STRATEGY IN CHINA

In China, the strategic guideline serves as the basis for China’s national military strategy. As the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping stated in 1977, “without a clear strategic guideline, many matters cannot be handled well.”

68

After 1988, the “strategic guideline” (

zhanlue fangzhen

) has been described as the “military strategic guideline” (

junshi zhanlue fangzhen

).

69

For the sake of consistency, I will simply use the term “strategic guideline” throughout.

The strategic guidelines are closely linked with the concept of strategy more generally. Within China’s approach to military science, the definition of military strategy remains influenced by Mao’s own writings. The 2011 edition of the PLA’s glossary of military terms defines strategy as “the principles and

plans for preparing for and guiding the overall situation of war,” including both offensive and defensive strategies.

70

Although the language is different, the essence is the same as the US military’s emphasis in its definition of strategy on the “how” of warfare.

71

The PLA’s definition of military strategy, however, remains abstract. Strategy can only be implemented when a series of principles for force planning, training, and operations are articulated and disseminated. China’s strategic guidelines contain these principles. As defined by the PLA, a strategic guideline is the “core and collected embodiment of military strategy.”

72

Similarly, Chinese military scholars describe the strategic guidelines as the “principal part and heart of strategy.”

73

Formally, the guidelines are defined as containing “the program and principles for planning and guiding the overall situation of war in a given period.” The guidelines cover both general principles about the whole process of military operations and concrete or specific principles for certain types of operations.

74

In short, the strategic guidelines outline how China plans to wage its next war.

Authoritative Chinese sources indicate that the guidelines have several components. One is the identification of the “strategic opponent” and “operational target,” based on a strategic assessment of China’s security environment and the perceived threats to China’s national interests.

75

Another is the “primary strategic direction,” which refers to the geographic center of gravity that will decisively shape the overall conflict as well as military deployments and war preparations. Perhaps the core component is the “basis of preparations for military struggle,” which describes the “form” or “pattern” of wars and operations that outline how war will be waged. The final component of a strategic guideline is the “basic guiding thought” for the overall use of military force and for the general operational principles to be applied in a conflict.

The strategic guidelines focus on conventional military operations. Available sources indicate that none of the nine strategic guidelines since 1949 provide explicit guidance for the use of nuclear weapons, though China’s nuclear strategy has been formulated to be consistent with the strategic guidelines in a general sense. The guidelines also do not provide guidance for noncombat operations, such as disaster relief or humanitarian operations. At times, such noncombat missions have been assigned to the PLA and were formalized under the rubric of the PLA’s New Historic Mission in 2004.

The formulation and implementation of the strategic guidelines should be viewed through the lens of how the CCP makes policy, not Western military planning. With one exception, China’s strategic guidelines have been drafted and adopted by the CMC. The CMC is not part of the PLA. Instead, it is a party committee under the Central Committee of the CCP that is responsible for guiding all aspects of military affairs. As a party committee, although the party’s top leader has always served as the chairman of this body, most other members (and usually all of them) represent the leadership of the PLA who

manage military affairs on behalf of the party. New guidelines are drafted by either the CMC’s general office or the leadership of the general staff department, which is often described as the CMC’s staff office or “

canmou

.” Unlike the drafting of the

National Defense Strategy

in the United States, direct civilian (or party) input is minimal. Party leaders usually approve only the general parameters for new strategic guidelines, usually in response to a suggestion by senior officers to change military strategy.

Once drafted, a new strategic guideline is adopted at an enlarged meeting of the CMC. These enlarged meetings gather together not just members of the CMC but also the leadership of the general departments, services, branches, military regions, and other top-level units in the PLA directly under the CMC. Typically, a new strategic guideline is introduced in a speech or report to the participants at the enlarged meeting. This speech has the same status as a work report to a CCP national party congress and its contents will be viewed as authoritative. Of the nine strategies identified for this book, however, the complete text of speeches introducing new guidelines is only publicly available for those adopted in 1977 and 1993. The 1956 strategic guideline, for example, was contained in a report delivered by Peng Dehuai when he was vice-chairman of the CMC and defense minister, but it has not been published openly.

The PLA, however, has no tradition of published doctrine where any officer (or soldier) can read a strategic-level document. Thus, the content of the speech introducing the new strategic guideline—and thus the new strategy—is transmitted within the PLA through a process of “

chuanda wenjian

” in which excerpts, key quotes, or a condensed version of the speech are distributed to lower-ranking units, usually in meetings convened by the leadership of these units. In 1980, for example, Song Shilun, the president of the Academy of Military Science (AMS), complained that “there are basically no complete written instructions of Comrade Mao Zedong on questions of the strategic guidelines. Instead, they have been mentioned only in parts of speeches from meetings and in conversations with party and military leaders.”

76

The strategic guidelines are just that—guidelines. Like high-level CCP policymaking, the adoption of a new strategic guideline represents only the beginning of a new strategy. They contain the major goals to be achieved and the principles that should guide the achievement of these goals. A new guideline usually does not outline in detail how the new strategy should be implemented or contain a definitive and complete list of the tasks needed to be carried out to accomplish what PLA sources describe as “national defense and army building.” The expectation is that the details will be fleshed out afterward in a way consistent with the objectives and principles in the guidelines. In many instances, the programmatic details are often determined when developing the next five-year plan for the armed forces.

To complicate the analysis of strategic decision-making, very little information about the guidelines is made publicly available outside of the PLA.

In general, enlarged meetings of the CMC are not reported in the military or party newspapers, which means that the content of these meetings is also not reported. Thus, a new strategic guideline is not announced outside of the PLA at the time when it is adopted. The 1956 guideline developed by Peng Dehuai, for example, was never announced in either the

Liberation Army Daily

(

jiefangjun bao

), the PLA’s main newspaper, or the

People’s Daily

(

renmin ribao

), the mouthpiece of the Central Committee of the CCP. Likewise, the first reference to the 2004 revision of the 1993 strategic guideline occurred afterwards, in a footnote in the last entry in Jiang Zemin’s

Selected Works

and only indirectly in the 2004 white paper on national defense.

77

Despite these challenges, several aspects of the process by which new strategic guidelines are formulated and disseminated make them well suited to explaining changes in China’s military strategy. First, because the guidelines are issued internally and not announced publicly, analysts can be confident that they are not being adopted as part of an effort to send signals to either foreign adversaries or domestic audiences. Second, unlike in some other militaries, new Chinese strategies are not adopted according to a timetable. The

Quadrennial Defense Review

in the United States and the

National Defense Program Outline

in Japan, for example, are issued according to a semipermanent schedule, every four and ten years, respectively. Instead, China’s strategic guidelines are formulated when the PLA’s leadership (with the consent of the top party leader) concludes that a change in strategy is necessary. For this reason, it should be easier to isolate those factors that prompt the adoption of a new guideline. Finally, the speed with which a new strategy can be adopted also facilitates identifying those factors that prompt the formulation of a new guideline, as they should be closely correlated in time.

IDENTIFYING MAJOR CHANGES IN CHINA’S MILITARY STRATEGY

Three indicators can be used to determine whether a change in a state’s national military strategy can be considered to be major or not. The essence of a major change in strategy is that it requires a military to change how it prepares to fight future wars. Specifically, it requires change in a military’s operational doctrine, force structure, and training.

Operational Doctrine

.

Operational doctrine refers to the principles and concepts that describe how a military plans to conduct operations. Operational doctrine is usually codified in field manuals or regulations and then distributed throughout the organization. A change in operational doctrine is considered a major change, based on two different criteria. The first is the content of the new doctrine and whether it represents a departure from existing doctrine. In 1982,

for example, the US Army issued a new edition of FM 100–5, which contained its basic operational doctrine. This edition reflected a dramatic departure from how the United States prepared to defend Western Europe through the adoption of a more offensive- and maneuver-oriented approach when compared with the 1976 edition of that same document.

78

The second is whether the new doctrine is disseminated to all the relevant units. If new doctrine is written, but not disseminated, then it is unlikely to influence how units train or how forces are equipped. In the early 1990s, for example, the British Army drafted a new doctrine for counterinsurgency operations. Only two hundred copies of the document were produced, however, and the British Army failed to adopt the doctrine until the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

79

In China, operational doctrine is contained in operations regulations (

zuozhan tiaoling

), which include combat regulations (

zhandou tiaoling

) and campaign outlines (

zhanyi gangyao

).

Force Structure

. Force structure refers to the composition of an armed force in terms of both the relative roles of different services (such as the army and the navy) and within a given service, its branches or combat arms (such as infantry and armor). Changes in inter- and intraservice force structure are an important indicator of strategic change because they involve the allocation of scarce resources within an organization and the relative capacity of different services to conduct specified operations. They may also reflect an underlying change in command structure.

A major change in military strategy can be reflected in force structure in different ways. First, strategic change could shift the allocation of resources and the relative importance of the different service branches. One example would be the strengthening of the navy at the expense of the army by reducing the army’s budget and shifting resources to the navy. Second, a new strategy could require the creation of new combat arms or other units in order to complete new tasks. Third, a new strategy could alter how units are equipped and armed. An infantry division, for instance, could be light, motorized, or mechanized depending on whether the unit is designed to be carried by vehicles into battle or walk to the fight on foot. Similarly, a navy could be equipped only with submarines, only with surface combatants, or some combination of both. Fourth, strategic change could alter how a particular service is organized. An army, for example, might use a division as the basic unit of organization or it might use smaller brigades. Finally, the types of weapons and equipment that a military provides its troops and whether it invests in the research and development for these weapons or purchases them abroad are also important indicators of organizational change.

Training

. Within any military organization, training is a costly and complex activity. How a military trains its troops, and how often, offers another window

into major change in military strategy. One component of training is the curriculum of the professional military education system and whether the system provides soldiers and officers with the skills that they need to implement the new strategy. If the curriculum is inconsistent with the content of the strategy, this suggests that the organization has not attempted to pursue major change. A second component of training is the frequency, scope, and content of military exercises and whether they are consistent with what is taught in the classroom and required by the strategy.

In China, the PLA has held fourteen army-wide conferences on military education since 1949. Many of these conferences were held in the 1950s, when China was establishing its professional military education system. These conferences aimed to provide guidance for China’s professional military education. As a result, they offer one potential source of data for measuring major military change.

80

Regarding training, the PLA has issued eight training programs (

dagang

) that provide guidance for the entire force in terms of the goals of military training and, in particular, how military exercises should be conducted annually. The issuance of these training programs, as well as the content of exercises held to implement them, can be used to determine whether a change in military strategy is a major one or not.

Table 1.1

provides a list of China’s nine strategic guidelines based on these criteria. As the table shows, the PLA has pursued major change in its military strategy in 1956, 1980, and 1993.

SHIFTS IN THE CONDUCT OF WARFARE

One external motivation for a major change in military strategy is a significant shift in the operational conduct of warfare. Assessments of such shifts are most likely to arise when a war occurs in the system that involves at least one of the great powers or a client of a great power who uses its patron’s weaponry and equipment. Key elements of change include the way in which military operations are conducted, such as how new equipment is used, how existing equipment is employed in new ways, and, more generally, how operations are executed and force is employed. Through an examination of the secondary literature on warfare after 1945, the key features of these past conflicts that might create a motivation for a state to alter or change its military strategy can be identified and summarized.

These key features, however, are distinct from the lessons that individual states might draw from these conflicts. In other words, even if scholars can agree on the main features of a conflict, states are likely to draw different lessons based on their own strategic circumstances and capabilities. The lessons that China might draw from particular conflicts are not necessarily the same ones that other states will identify. One should probably expect a great deal of variety in

the lessons that states draw. A study of reactions to the Gulf War, for example, demonstrates the wide variation in lessons that states inferred shortly after that war.

81

As this study examines the period after 1949, the context for all the potential shifts in the operational conduct of warfare that might shape military strategy starts with the experience of World War II. Although the key features of this conflict cannot be summarized in a paragraph, several should be noted.

82

The first is the continued mechanization of warfare based on weapons first developed and deployed in World War I, especially tanks and airplanes, in addition to advances in artillery, all of which increased lethality and destructiveness. The second is the vast amounts of ammunition and supplies that were consumed because of the mechanization of warfare and the ability of states with industrialized economies to produce such large amounts of weapons and equipment. The third is the development of combined arms operations in which different types of units such as infantry and artillery were combined to achieve even greater lethality on the battlefield. The fourth is the attention drawn to the operational level of war, especially by the performance of the German Army in the opening years of the conflict.

Since 1949, there have been ten interstate wars involving a great power or its client using the great power’s equipment and doctrine. These wars are the 1950–53 Korean War, the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, the 1971 Indo-Pakistani War, the 1973 Arab- Israeli War, the 1980–88 Iran-Iraq War, the 1982 Lebanon War, the 1982 Falklands War, the 1990–91 Gulf War, the 1999 Kosovo War, and the 2003 Iraq War. Counterinsurgency wars, such as those involving the United States in Vietnam or the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, are excluded because these are unlikely to reveal major lessons for conventional wars, which are the focus of great power military strategy.

83

Among scholars of military history and operations, the 1973 Arab-Israeli War and 1990–91 Gulf War are viewed as having the greatest impact on how states viewed the conduct of warfare.

84

China should be most likely to change its military strategy in response to these conflicts.

PARTY UNITY

Unity and stability within a communist party refers to acceptance and support of the party’s policies by its leaders as well as consensus among the top leaders about the distribution of power within the party. Of course, party unity is hard to observe, especially in Leninist political parties that abhor public displays of discord or disunity. Moreover, party unity should ideally be measured independent of observable instances of leadership conflict, such as the purge of top leaders, but such measures may not be possible. Nevertheless, the degree of unity can be measured in several different ways

.

One measure of disunity would be change in the appointed successor to lead the party. Such change could be the product of factional politics within the party that are harder to observe.

85

Such change was more common in the Mao era and for most of the Deng era than under Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, or Xi Jinping. Liu Shaoqi was Mao’s chosen successor until 1966. Then, Lin Biao was anointed as the successor until his mysterious death in a plane crash in 1971. Hua Guofeng became Mao’s chosen successor just months before Mao’s death in 1976, which sparked a power struggle with Deng Xiaoping. Even the 1980s remained volatile, as two individuals served as general secretary of the CCP, Hu Yaobang (1980–1987) and Zhao Ziyang (1987–1989), but their removals were supported by the top party leadership. Under Jiang Zemin (1989–2002), greater stability emerged, as Hu Jintao, whom Deng chose to succeed Jiang, became general secretary in 2002. The anointed successor to Hu, Xi Jinping, was placed on the Politburo Standing Committee at the Seventeenth Party Congress in 2007.

86

Xi, however, has not yet named a successor.

Another measure of unity in the party is the continuity of membership in the leading bodies of the party. The top governing body is the Central Committee of the CCP, whose members are elected at party congresses. The real power, however, is held by smaller bodies, the Politburo and especially the Politburo Standing Committee. The Politburo is typically composed of top leaders from the most important bureaucracies and provinces. The Politburo Standing Committee is composed of a small group of leaders who assume direct responsibility for different aspects of party and state affairs.

87

Changes in the composition of these bodies offer one indicator of disunity and instability in the party, especially if existing members who meet the criteria for membership are not reelected, if new members are suddenly added, or if large numbers of current members are removed. Likewise, continuity in the membership of these bodies is perhaps an important indicator of unity. A related indicator might be the creation of new leadership bodies outside the existing structure of the party. In the early years of the Cultural Revolution, for example, the Cultural Revolution Group assumed some of the powers of the Central Committee and the Politburo.

A final measure of unity concerns agreement over the party’s core policies and guidelines. The greater the debate over policy, the greater the potential disunity. Perhaps the paradigmatic case is Deng’s efforts to maintain support for his broad reform agenda after the 1989 massacre in and around Tiananmen Square. Until his “southern tour” in mid-1992, consensus over whether to continue with reform and opening, and at what pace, divided the leadership. Nevertheless, by the Fourteenth Party Congress in October 1992, Deng had managed to rebuild consensus for his policies in the Central Committee and other leading bodies.

8

8

SOURCES

This book exploits the increasing availability of Chinese language materials about the PLA. Many of these materials have only been published in the past decade or were published earlier but have only recently become more accessible to scholars outside of China. Perhaps one of the most important sets of Chinese language materials is party history sources published by military and party presses. Several different types are now available, compiled by teams of party historians. The first are official chronologies (nianpu

), which record the daily activities of top military and party leaders and can contain excerpts of key speeches and reports not always found in other sources in addition to descriptions of important meetings and events. The second party history source is collections of selected documents (wenxuan

), selected works (xuanbian

), manuscripts (wengao

), and expositions (lunshu

), which include speeches, reports, and other documents, many of which are being published for the first time.

Another, more general type of Chinese language materials used for this study is the biographies and memoirs of military leaders. Most biographies (

zhuan

) are official publications, usually compiled under the direction of either the General Staff Department or the General Political Department and published by the PLA’s Liberation Army Press. These biographies are written by compilation teams composed of party and military historians, as well as members of the leader’s personal staff. Although biographies are usually published only after a leader has died, many key military leaders since 1949 have published their memoirs (

huiyilu