4

The 1964 Strategy: “Luring the Enemy in Deep”

In June 1964, Mao Zedong intervened directly in military affairs and changed China’s military strategy. He rejected the identification of the northeast as China’s primary strategic direction where a US invasion might occur and the use of a forward defense to counter such an attack. Over the next twelve months, Mao would reorient China’s military strategy around the concept of “luring the enemy in deep,” in which territory would be yielded to an invader to defeat it in a protracted conflict through mobile and guerrilla warfare.

The adoption of the 1964 strategic guideline presents an anomaly. It represents the one instance when a top party leader initiated a change in military strategy. The other eight strategic guidelines adopted since 1949 were initiated by senior military officers. It also represents an example of a reverse or retrograde change in strategy, in which an older strategy replaces a current one. The 1964 strategy was not a major change based on a new vision of warfare or a minor change that adjusted elements of an existing strategy. Instead, as discussed in

chapter 2

, luring the enemy in deep was a concept of operations developed during the encirclement campaigns in the 1930s, when the Red Army sought to defend itself against a much stronger Nationalist force. Mao now sought to use this idea as the organizing principle for countering a US attack.

Mao’s intervention to change China’s military strategy is puzzling because China did not face an immediate or pressing external threat that would warrant such a dramatic reversal in how to defend China. China’s security environment had deteriorated in 1962, producing a large-scale mobilization to defeat a feared Nationalist invasion in June and then a border war with India in October and November. Yet these threats had diminished by 1963 and had

certainly dissipated by 1964. Although the United States was increasing the number of military advisors in South Vietnam, by mid-1964, there were still no indications that the war in Vietnam would expand beyond the seventeenth parallel toward China’s border. Despite ideological tensions with the Soviets, China’s northern border did not start to be militarized until the very end of 1965. Finally, China successfully tested its first atomic bomb a few months after Mao changed strategy, an event that should have significantly increased China’s security and confidence about preventing an invasion.

The adoption of the 1964 strategy illustrates how party disunity and leadership splits can distort and politicize strategic decision-making. In the early 1960s, Mao became increasingly concerned about the threat of revisionism within the Chinese Communist Party, which would prevent the continuation and deepening of China’s revolution. Mao pushed for a strategy of luring in deep not to enhance China’s security, but instead as part of a broader attack on party leaders whom he viewed as revisionists, including the decision to industrialize China’s hinterland by “developing the third line” (

sanxian jianshe

). These efforts would culminate with the launch of the Cultural Revolution two years later.

Understanding the origins of the 1964 strategic guideline is important for several reasons. One reason is that the strategy of luring the enemy in deep shaped China’s military strategy for more than a decade. It would not be abandoned until September 1980, when the second major change in China’s military strategy occurred. After the clash with the Soviet Union at Zhenbao Island in March 1969, China maintained this strategy of strategic retreat. By that point, too, the split within the CCP leadership and the PLA’s leading role in maintaining law and order likely prevented the formulation of a new strategy. Another reason is that the origins of the 1964 guideline highlight that Mao himself never stated during this period (or before 1969) that China needed to prepare to fight “an early, major, nuclear war” (

zaoda, dada, da hezhanzheng

).

1

Although China acknowledged that a war with the United States would involve nuclear weapons, the phrase did not become commonly used until after China faced the Soviet threat in 1969. Finally, it offers a revisionist interpretation of Mao Zedong’s own motivations. In most Chinese and Western histories of the period, Mao’s approach to the third line and military strategy is portrayed as a response to growing external threats. This chapter suggests that internal threats, in the form of revisionism, were the decisive factor in Mao’s calculus.

This chapter proceeds as follows. The first section examines the year of 1962, when China faced increased threats from many directions simultaneously. In response, China implemented its existing strategy of forward defense, mobilizing to counter a Nationalist invasion along the coast and then attacking Indian forces along the disputed border. The next section describes the content of the strategic guideline initiated in 1964, to show that it constituted a reverse

or retrograde change to China’s existing strategy. The third section outlines the political logic of Mao’s intervention and how his concerns about revisionism within the CCP led him to call for the development of the third line and decentralization of economic policy under the guise of a general exhortation to prepare for war. The fourth section examines the process by which the 1964 strategy was changed, highlighting how Mao’s concerns about revisionism and his desire to industrialize the hinterland also required a decentralized approach to military strategy under the idea of luring the enemy in deep. The final section examines briefly the continuity of this strategy after a Soviet invasion became the most pressing threat to China’s security in 1969.

New Threats and Strategic Continuity in 1962

In early January 1960, the CMC assessed that China faced a relatively stable external security environment. Mao’s own judgment was that neither a major war nor nuclear war was likely to occur. Similarly, in February 1960, Su Yu noted the weakness and vulnerabilities of the United States versus the socialist bloc.

2

Nevertheless, consistent with earlier assessments of the mid-1950s, Mao also believed that “so long as imperialism exists, the threat of war still exists.”

3

Marshal Ye Jianying observed that China should continue to prepare for the worst and “focus on the most dangerous aspects.”

4

Thus, China’s military strategy remained the same as before, adopting a forward defensive posture to defend against a “surprise attack” (

turan xiji

).

5

By mid-1962, however, China’s external security environment had deteriorated. In June, China faced simultaneous threats from multiple directions, including across the Taiwan Strait and along the disputed boundary with India as well as from the Soviet Union adjacent to Xinjiang. Yet, facing these threats, China did not change its military strategy. Instead, Beijing moved to improve combat readiness (

zhanbei

), in which the force was reorganized, growing from roughly 3 million soldiers in 1961 to 4.47 million by early 1965.

6

China also responded to the most immediate and severe threat of the time, a potential Nationalist assault, by mobilizing forces and adopting a forward defensive posture to repel the invasion—actions consistent with its existing military strategy. The new threats that arose did not warrant a new military strategy. When Mao rejected the existing strategy in June 1964, he did so not to counter external threats and enhance China’s security, but instead to pursue his domestic political agenda.

“THREATS IN ALL DIRECTIONS”

The context for the deterioration of China’s security environment was the election of John F. Kennedy as president of the United States, the shift to “flexible

response,” and the expansion of the US military. As Zhou Enlai noted in February 1962, “The enemy is expanding its force and preparing for war [

kuojun beizhan

].”

7

Of particular concern was the “two-and-a-half” doctrine, which suggested that the United States was preparing to wage war in Asia and Europe simultaneously. In June 1962, Zhou stressed the threat posed by the growing presence of the United States, observing that “Southeast Asia is a strategic area and the place where American imperialism is competing for the long term.”

8

China viewed the establishment of the US Military Assistance Command and the increase in US advisors in Vietnam by the end of 1962 as part of an effort to encircle China, but this reflected the continuation of hostility between the two countries from the 1950s and not a specific threat.

9

The most direct threat to China was a Nationalist invasion, especially if supported by the United States. Sensing weakness on the mainland after the Great Leap, Chiang Kai-shek saw a window of opportunity to strike. In his 1962 Chinese New Year’s speech, Chiang made bellicose statements about an imminent Nationalist return to the mainland.

10

In March, the Nationalist government issued a conscription mobilization decree to increase manpower, adopted a special budget for wartime mobilization efforts, and imposed a “return to the mainland” tax to help fund the effort.

11

By late May, China’s leaders concluded that a Nationalist attack was likely. According to the CMC’s strategy research small group, the Nationalists “will certainly seize the opportunity of our economic difficulties to come and attack us [

gao women

]” because it presented “an exceedingly rare good opportunity.” The group concluded that “the probability of hostilities occurring was greatest along the southeast coast.”

12

In early June, Zhou Enlai assessed the most likely scenario was the seizure of several beachheads on the Fujian and Zhejiang coasts that would be used as bases for surging forces and launching larger attacks on the mainland.

13

As tensions grew across the Strait, China faced a second, albeit lesser, threat on its western flank in Central Asia adjacent to the Soviet Union. From late April to late May 1962, more than sixty thousand ethnic Kazakhs fled from Xinjiang to the Soviet Union, during which a large riot erupted in the city of Yili (Kulja) on May 29, 1962. China accused the Soviet Union of encouraging this exodus by issuing false citizenship papers to Xinjiang residents in the cities of Yili and Tacheng (Qoqek), spreading print and radio propaganda about opportunities in the Soviet Union, and opening gateways in the border fence to facilitate emigration. From China’s perspective, the Soviet Union was seeking to destabilize a part of the country where the central government’s authority was weak, while also exposing China’s lack of border defenses and border control in the area. Although the “YiTa Incident” did not threaten to start a war or even a military clash, it underscored China’s sense of insecurity in 1962.

14

Finally, in the southwest, India began a “forward policy” of occupying disputed territory on the China-India border. Implementation of the policy

started in the eastern sector around Tawang in February 1962 and in the western sector in the Chip Chap Valley in March 1962. In mid-April, China announced that it would resume patrols in the western sector, and the General Staff Department (GSD) ordered troops in Xinjiang to strengthen border defenses. By the end of May, the GSD issued a report on strengthening combat readiness along the border, and instructions regarding the deployment of forces, supplies, fortifications, and combat readiness training (

zhanbei xunlian

). Nevertheless, Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai both indicated that a Nationalist attack posed the primary threat and ordered that China should fight only if attacked by India first.

15

CHINA’S RESPONSE TO EXTERNAL THREATS

China responded to these threats in several different ways. Taken together, however, they did not prompt China to reevaluate the utility of its existing military strategy. Instead, China moved to enact its existing strategy.

16

China mobilized to counter a Nationalist invasion by preparing to execute a forward defense in the likely areas of attack.

Before the emergence of new threats in 1962, the PLA was implementing an eight-year organization and equipment plan (

zuzhi bianzhi jihua

) approved in October 1960. Consistent with the existing strategy, this plan marked the PLA’s continued transformation from a light infantry force to a combined force composed of multiple services and branches. The plan focused on modestly expanding the size of operational and combat-duty troops; strengthening air, naval, and specialized units as the production of new equipment would permit; strengthening forces in border areas; and establishing engineering and research units. By September 1961, the PLA grew by approximately three hundred thousand to three million.

17

During this process, many shortcomings were identified, which suggested that further reorganization was needed. Areas identified for future reform included oversized departments (

jiguan

), a surplus of officers, understrength infantry units (especially those engaged in border and coastal defense), and the limited mobility of units below the division level.

18

In February 1962, before the extent of the deterioration of China’s security environment became clear, the CMC convened an army-wide meeting on organization and equipment to address these shortcomings. This meeting would last for several months. At the end of February, Zhou Enlai participated in the meeting and said that military work should emphasize “reorganizing the military, improving combat readiness [

zhengjun beizhan

].”

19

The meeting determined the principle of reorganization would be the “four lightens and four strengthens” (

si qing si zhong

). This slogan called for concentrating heavy weapons in units in the north and at the army level and above, while those in the south and at lower levels would be more lightly armed. Noncombat departments (

jiguan

) should be reduced while operational units (

liandui

) should be increased.

20

The plan also sought to improve the mechanization of troops in the north and on coastal islands that would be the first line of defense in an invasion, while those in the south would remain equipped as light infantry units, owing to the tropical terrain that limited mobility of motorized vehicles.

21

Because of the challenges of arming the ground forces with new weapons, fifty-five percent of infantry divisions would be designated as full-strength combat-duty divisions to be equipped with the best equipment. By contrast, twenty-seven percent were designated as ordinary divisions that would engage in economic production for half the year, and eighteen percent as “small” divisions that would focus on training.

22

China responded to the threat across the Strait with the largest mobilization of forces since the Korean War.

23

Consistent with a strategy of forward defense, the operational guideline for countering a Nationalist attack was to “resist [

ding

]

,

do not let the enemy come.”

24

At the end of May, Shandong, Zhejiang, Fujian, Jiangxi and Guangdong provinces were instructed to prepare for conflict. Along the southeast coast, thirty-three infantry divisions, ten artillery divisions, three tank regiments, and other forces were placed on high alert.

25

An additional one hundred thousand veterans were mobilized to supplement these forces and efforts were begun to mobilize an additional one hundred thousand militia members.

26

On June 10, 1962, the CMC issued “Instructions for Smashing Nationalist Raids in the Southeast Coastal Area,” which implemented a widespread domestic mobilization in coastal provinces.

27

In June and July, seven combat-duty divisions, two railway corps divisions, and other specialized units from Liaoning, Hebei, Henan, and Guangzhou were deployed to Fujian while the air force placed almost seven hundred planes on alert status.

28

All told, the PLA mobilized approximately four hundred thousand soldiers and one thousand planes to repel an attack.

29

The threat began to dissipate after a meeting between US and Chinese ambassadors in Warsaw on June 23. The United States indicated that Washington did not encourage Chiang’s current efforts and would provide no military support to Taiwan in the event of a Nationalist assault.

30

Nevertheless, concerns about the security of China’s coastal areas dominated PLA planning for the next few years. In October 1962, to emphasize its commitment to coastal defense, the Fuzhou Military District adjacent to Taiwan organized a large-scale, live-fire anti-landing exercise with approximately 36,500 soldiers.

31

In 1963 and 1964, the defense of coastal islands would become a focal point in PLA operations planning, as the islands constituted the outer limit of China’s first line of defense against an attack.

32

As tensions eased across the Strait in the summer of 1962, the situation on the China-India border deteriorated. In September, a stand-off in the eastern sector over an area named Chola (Dohla) precipitated an escalation of tensions. In mid-October, China decided to attack Indian units that had been deployed

as part of the “forward policy” and attacked Indian forces in both sectors on October 20. After pausing to press India to hold talks, China attacked again in November, destroying the remainder of Indian forces in disputed areas before declaring a unilateral halt to hostilities and withdrawing to the line of actual control before the conflict started.

33

By the end of 1962, China’s security environment stabilized. The Nationalist invasion did not occur, while the PLA readily defeated Indian forces. Nevertheless, the size of the PLA grew significantly in 1963 and 1964. Although the 1962 reorganization plan called for maintaining the current size of the armed forces, the increase was consistent with growing threats and the need to increase combat duty units and address multiple threats simultaneously. In late 1961, the size of the force was approximately three million. Starting in 1963, it began to grow, reaching 4.47 million at the start of 1965.

34

Reflecting the focus on external threats, just over seventy-nine percent of the force consisted of combat troops (

zuozhan budui

), a share what would fall to just over fifty percent when the force expanded again after 1969 in the Cultural Revolution.

35

“Luring the Enemy in Deep”

In June 1964, Mao Zedong rejected the existing military strategy of forward defense during a speech at the Ming Tombs outside Beijing. Instead, Mao envisioned luring the enemy in deep, allowing an adversary to occupy territory, and then defeating it through a protracted war that would leverage China’s large territory and population.

Among all of China’s military strategies since 1949, the 1964 strategic guideline represents an anomaly. First, it envisioned a return to a familiar way of warfighting, not a new vision of warfare, and thus did not require the PLA to pursue major organizational reforms. Second, the new strategy was not codified in a report drafted, discussed, and approved by China’s senior military officers. Instead, it was based on the various remarks Mao had made over the following year. In 1980, Song Shilun, the president of the Academy of Military Science, lamented that only “fragments” of Mao’s remarks on strategy from this period were available.

36

The 1964 military strategy remained premised on countering a US invasion. Nevertheless, Mao changed the core components of the existing strategic guideline revised in 1960. The first was a change in the “primary strategic direction.” China’s existing strategy was premised on a US assault on the Shandong Peninsula. Nevertheless, Mao believed that the direction of attack was uncertain and could occur anywhere along the coast, from Tianjin down to Shanghai. Therefore, China could no longer rely on “resisting in the north, opening in the south,” which had been premised on a forward defense of northern areas, especially the Shandong Peninsula. The broader implication was that China

did not have a primary strategic direction around which to orient its military strategy and would need to prepare for an attack from multiple directions.

The second change followed from the absence of a primary strategic direction and concerned the “basic guiding thought for operations.” The concept of operations from the civil war—luring the enemy in deep—replaced the emphasis on defending fixed positions. Luring the enemy in deep was a form of strategic retreat, in which an adversary would be allowed to gain a foothold on China’s territory so that the PLA could then engage an enemy in a protracted war of attrition. In turn, mobile and guerrilla warfare replaced positional warfare as the main form of operations that the PLA should be able to conduct.

The 1964 strategy remained a strategy of strategic defense. The main objective of the 1964 strategy was to defeat an adversary through a protracted conflict on Chinese territory. Mao envisioned ceding territory to an invader, including major cities, so that it would extend its supply lines and be degraded through a protracted conflict, in which soldiers as well as civilians would be mobilized.

37

In other words, Mao envisioned that PLA main force units would remain the core fighting force, but that they would be supplemented by local armed forces and militia that would be able to conduct independent operations in different parts of the country. Guerrilla warfare would be waged in areas ceded to the adversary, while main force units would engage in mobile operations on fluid fronts in China’s interior.

With the launch and upheaval of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, it is impossible to observe the implementation of the 1964 strategy. Thus, the main change examined in this chapter is Mao’s rejection of the existing strategy for a variant of an older one, not the implementation of the new strategy. In general terms, the return to mobile warfare and luring the enemy in deep did not require the PLA to develop new operational doctrine. Instead, it only required the PLA to revive its “glorious traditions” from the civil war. No effort was made to draft new operational doctrine. The size of the force grew significantly, from 4.47 million in early 1965 as the strategy was changing to 6.31 million by 1969. Much of this growth occurred after the clash with the Soviet Union over Zhenbao Island in March 1969, though nineteen divisions were formed or reorganized between 1966 and 1968.

38

The PLA did not draft a new training program, though the training that did occur increasingly emphasized studying politics and not military affairs.

Mao pushed for the change in strategy to address the potential US threat to China only. Nevertheless, China continued to adhere to the 1964 strategic guideline after the Soviet threat replaced the American one in 1969. Whether or not it was an appropriate strategy for dealing with a ground invasion, the strategy could not be altered because of the deep divisions in the party and military leadership created by the Cultural Revolution

.

The Political Logic of Mao’s Intervention

Mao changed China’s military strategy in 1964 to counter revisionism and internal threats to his revolution rather than external threats to China’s security. In the aftermath of the Great Leap Forward, Mao became increasingly concerned about the potential for revisionism within the CCP, as the party leadership returned to conventional central planning practices and strengthened the role of the party’s central bureaucracy. It was these practices that Mao had sought to circumvent when he launched the leap. To challenge these tendencies and to again decentralize decision-making, he called for “developing the third line,” or the massive industrialization of China’s southwestern hinterland that would consume just over half of all capital investment in the Third Five-Year Plan.

39

The change was so radical that Mao could only justify it by the need to prepare for war, which also dictated that he intervene to change China’s military strategy as well as its economic policy.

The argument that Mao championed—developing the third line and changing China’s military strategy in 1964 to counter internal threats and not external ones—is itself a revisionist interpretation of this period. Almost all scholarship and histories from inside and outside China highlight the deterioration of China’s security environment as the reason why Mao pushed for development of the third line.

40

The only exception is an essay by a party historian, Li Xiangqian, that questions the role of the escalation of the war in Vietnam in Mao’s decision to develop the third line and suggests that Mao may have also harbored domestic motives.

41

GROWING CONCERNS ABOUT REVISIONISM

Revisionism refers to an unacceptable departure from orthodox Marxist-Leninist ideology that eventually leads to socialist degeneration. After the Great Leap Forward, Mao concluded that the greatest danger to China’s revolution was not an external attack. Instead, the main threat was internal—the “restoration of capitalism” led by “revisionists” within the CCP. Mao’s efforts to combat revisionism would culminate two years later with the launch of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

42

Mao targeted the CCP’s senior leadership, most of whom were purged in 1966, as well as the vast, centralized bureaucracy that they had created to govern the country, which Mao hoped to rectify through a “mass insurgency” from below.

43

Mao’s motives, of course, were mixed, as he sought to preserve both his own power within the CCP and the legacy of China’s revolution, as he defined it. Nevertheless, he viewed threats to his power through an ideological lens, as ideological threats.

Mao’s fear of revisionism within the CCP began in the aftermath of the Great Leap Forward. In launching the Great Leap, Mao aimed to circumvent

the Soviet-style approach that China had used in the First Five-Year Plan to achieve rapid growth by applying well-honed techniques of mass mobilization to the economy.

44

In practice, the policies of the leap weakened the control of the central bureaucracy over the economy and empowered local party leaders, who had become responsible for achieving ambitious production goals. Farmers were organized into large communes in the countryside to dramatically increase surplus grain that could then be used to support investment in heavy industry. As Andrew Walder writes, the Great Leap was a “political campaign that cast economic policy in terms of political loyalty, equating it with class struggle.”

45

The Great Leap, however, was a great failure. Grain output fell from 200 million tons in 1958 to only 143 million tons in 1961. Only in 1966 would grain output surpass 200 million tons again.

46

Likewise, from 1960 to 1962, industrial output fell by fifty percent and only exceeded the level output from 1958 in 1965.

47

Tens of millions of Chinese citizens perished in famines throughout the country, with estimates ranging from 30 to 45 million deaths.

48

As the calamity mounted at the end of 1960, the party started to take steps to stem the crisis and rebuild the economy. Taken together, these measures sought to reestablish the bureaucracy’s control over the economy, taking it back from the party. In practice, retrenchment involved lowering production targets, terminating mass mobilization, dismantling communes, and increasing material incentives for farmers under the slogan (approved in January 1961) of “adjustment, consolidation, replenishment, improvement” and prioritizing agriculture over industry. The goal was to return the rural economy to how it had been organized before the start of the Great Leap.

49

The economic and human devastation created by the Great Leap raised questions about the efficacy of Mao’s leadership. By early 1962, top party leaders had begun to blame the party’s policies, and thus Mao himself, for the catastrophe. To encourage support for the recovery effort and “unify thought,” the party center in January 1962 convened an unprecedented meeting of over seven thousand cadres from the party center to the county and factory level.

50

Top party leaders criticized the party’s role in the crisis. Liu Shaoqi, then the party’s vice-chairman and Mao’s successor, even suggested that the famine was “three tenths natural disaster, seven tenths man made calamity.”

51

Mao could only view such a remark as a direct criticism.

52

In 1959 and 1960, Mao stated repeatedly that the “accomplishments” of the Great Leap could be counted on nine fingers while the “setbacks” could be counted on only one.

53

Liu publicly reversed this assessment, criticizing Mao before the largest meeting of party cadre ever held since 1949.

Mao did offer a rare, if vague, self-criticism at the conference. Nevertheless, the criticisms of the policies that produced the catastrophe, and blaming the party in addition to natural disasters, raised questions for Mao about the loyalty

of the leaders in charge of day-to-day policymaking, like Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping (secretary-general of the Central Committee Secretariat), and their commitment to continuing Mao’s revolution. At the end of 1958, Mao started to delegate responsibility for the party’s daily affairs to Liu and Deng by deciding to move himself to the “second line,” and stopped attending Politburo meetings on a regular basis. Mao was beginning to regret that decision.

In early 1962, Liu and Deng redoubled their efforts to rescue the economy by reestablishing central control. Economic recovery measures were put in place to restore balance between the rural and industrial economies, primarily by reducing investment in industry to increase support for agriculture. These measures included policies such as reducing the urban population, decreasing investment in capital projects, and continuing experiments with household farming methods like the household responsibility system, to create material incentives for increasing production. Liu and Deng also started to reexamine the cases of some cadres persecuted in the Anti-Rightist Movement in 1958, a topic that Mao had opposed when it was raised at the seven thousand cadres conference.

54

The Liu and Deng approach rolled back Mao’s emphasis on decentralization and empowering localities, marking a return to the more centralized, bureaucratic, and technocratic approach to economic policy that Mao had rejected when he launched the leap.

By the summer of 1962, Mao was becoming alarmed. He was especially concerned with the household farming system, which set quotas for output and allowed farmers to keep any surplus production. At the same time, the party began to loosen restrictions on intellectuals in a bid to tap their expertise to aid the recovery.

55

In July, during a tense exchange with Liu Shaoqi, Mao accused Liu of abandoning the revolution, asking, “What will happen after I die?”

56

In August 1962, at the annual leadership retreat at Beidaihe, Mao revealed his reservations to a wider audience. He criticized what he viewed as excessive pessimism in assessments of the situation and noted the danger that household farming could increase class polarization. He also underscored the need to continue with the collectivization of agriculture and not reversing verdicts on those deemed as rightists, especially Peng Dehuai.

57

Mao’s concerns about revisionism and the importance of continuing class struggle featured prominently in the Tenth Plenum in September 1962. He laid down a marker in the plenum’s communiqué, which he edited, noting that “class struggle cannot be avoided” because there were some people who “intend to depart from the socialist road and go along the capitalist road.” Moreover, “this class struggle will inevitably be reflected in the party.” Thus, the communiqué warned, “While struggling against class enemies at home and abroad, we must be vigilant and resolutely opposed to all types of opportunistic ideological tendencies within the party.”

58

As party historians would later observe, Mao at the meeting outlined his “basic strategy” of “opposing revisionism and preventing

revisionism” (

fanxiu fangxiu

) at home and abroad.

59

The imperative of continuing class struggle to prevent the “restoration of capitalism” would prompt Mao’s decision to launch the Cultural Revolution four years later.

60

Despite raising the question of class struggle, the economy remained fragile and the plenum agreed to continue with recovery measures. Although Mao emphasized class struggle, he was unable to pursue it at the expense of the economy. In April 1963, an enlarged meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee decided that “opposing revisionism” would focus on growing tensions with the Soviet Union over the direction of the worldwide communist movement. The party published nine open letters or polemics between September 1963 and July 1964 that denounced Soviet revisionism in its foreign and domestic policies and delegitimized its leadership. Many of the critiques of the Soviet Union, however, reflected Mao’s concerns about the CCP’s own trajectory. The Politburo Standing Committee also decided that “preventing revisionism” at home would start with the Socialist Education Movement.

61

The movement began with the “four cleans” (

siqing

) in the countryside and “five antis” (

wufan

) in the cities, and would continue until the start of the Cultural Revolution.

62

By 1964, the trends that would push Mao to attack the CCP’s leadership and launch the Cultural Revolution were present. The party’s top leadership favored pragmatism over ideology. The central bureaucracy had regained authority over the vast majority of enterprises and the allocation of goods that it had lost during the Great Leap.

63

The State Council had returned to its size in 1956, before the start of the Great Leap.

64

Even the Socialist Education Movement emphasized strengthening party organization and combating corruption, not rooting out revisionism and engaging in class struggle.

65

As Walder writes, the ninth polemic against the Soviet Union published in July 1964 “expressed what was to be the ideological justification for the Cultural Revolution.”

66

The document decried the domestic and foreign policies of “the revisionist Khrushchev clique” before asking whether “genuine proletarian revolutionaries” would maintain control of the party and the state in China. The selection of revolutionary successors, the letter concluded, was “a matter of life and death for our Party and our country.”

67

MAO ATTACKS ECONOMIC PLANNING

In mid-March 1964, Mao decided that he would now focus on revisionism inside China. His decision was announced at a Politburo Standing Committee meeting to discuss an upcoming central work conference. He informed his colleagues that “in the past year, my main efforts have been spent on the struggle with Khrushchev. Now I should turn back to domestic issues, connecting [

lianxi

] opposing revisionism and preventing revisionism internally.”

68

Mao’s decision

to focus on domestic revisionism set the stage for a clash over economic policy, from which he had retreated in late 1958.

One main topic for the central work conference was the draft framework of the Third Five-Year Plan. The State Planning Commission began to work on the plan in late 1962 and emphasized the recovery of the economy. Li Fuchun, head of the State Planning Commission, proposed that the plan concentrate on agricultural output and the production of “food, clothing, and daily necessities” (

chi, chuan, yong

).

69

Basic industry and national defense would be secondary priorities. In the summer of 1963, Mao agreed with Li Fuchun’s suggestion to postpone the start of the Third Five-Year Plan to give the economy more time to recover. The period from 1963 to 1965 would be a “transitional stage” between the second and third five-year plans, again with a focus on agriculture.

70

Bo Yibo, Li’s deputy on the State Planning Commission, recalls that, during this transitional period, “agriculture was first, basic industry second, and national defense third.”

71

In early 1964, Li Fuchun’s approach to the Third Five-Year Plan remained focused on these objectives. The draft framework circulated in April 1964 contained three main tasks to be accomplished. The first task was “greatly developing agriculture, basically resolving the people’s issue of food, clothing and daily necessities.” The second and third tasks were to “appropriately develop national defense, striving for breakthroughs in sophisticated technology,” and to strengthen basic industry.

72

In other words, national defense and basic industrial development remained lower priorities and would only be pursued if they did not harm the recovery of the economy based on agriculture.

73

According to Bo Yibo, agriculture would be the “foundation” of “planning.”

74

Yet on the eve of the central work conference, Mao attacked the approach to economic policy that he had previously endorsed. Instead of supporting the emphasis on agriculture, he called for the industrialization of China’s hinterland

75

or “developing the third line.”

a

When Li Fuchun briefed Mao in early May, Mao responded that defense and heavy industries should receive greater attention, thereby negating the priorities in the draft framework of the plan. He said he “could not relax” if steel mills at Panzhihua (in Sichuan province) and Jiuquan (in Gansu province) were not built, asking “what should be done if a war erupts” and China lacked such industrial plants.

76

These projects had been initiated in 1958 and later postponed because of the economic crisis.

77

Mao also observed that “defense industries” should be a “fist” for the economy as well as agriculture, indicating he believed that they should play an equally

important role in the economy.

78

As Li Fuchun’s biographers observe, Mao now viewed “the starting point for the Third Five-Year Plan as more about preparing for war.”

79

When the central work conference began, Mao attacked the framework for the Third Five-Year Plan before the party’s top leadership. During a meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee on May 27, he argued that the plan paid insufficient attention to the development of China’s “butt” (basic industry) and rear (

houfang

) or the “third line.” Mao observed that “in the nuclear age, it is unacceptable to have no rear area.”

80

He further suggested that, over the next six years, “a foundation should be established in the southwest” with industrial bases for metallurgy, national defense, oil, railroad, coal, and machinery.

81

The main reason for developing the third line was to “prepare for the enemy’s invasion” (

fangbei diren de ruqin

).

82

Mao’s intervention was remarkable and must have surprised Li Fuchun and other top leaders. Available sources contain no instances of Mao ever referring to the third line before this meeting.

83

The immediate effect of his intervention was to transform the focus of the conference. The next day, May 28, Liu Shaoqi transmitted Mao’s instructions on developing the third line to the work conference’s leading small group, thereby altering the direction of the conference in a way that none of the participants had anticipated when it started.

84

Although Mao had avoided economic policy since the Great Leap, he had decided to reengage. His intervention could not be ignored.

On June 8, Mao participated in the central work conference for the first time, chairing an enlarged meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee. In various remarks at this session, he connected his concerns about revisionism with his critique of the Third Five-Year Plan and the need to develop the third line.

85

He criticized China’s method of planning, which was “basically learned from the Soviet Union” and simply “using a calculator.”

86

Mao thus implied that China’s approach to planning, and those executing it, was revisionist. This method, he charged, was “not suited to reality” because it could not account for unexpected events that might arise, such as natural disasters or wars. Revealing his dissatisfaction, Mao asserted that “[we] must change the method of planning.” He described such a task as a “revolution,” as once the Soviet approach was adopted it was hard to change, and critiqued not only the content of the framework for the Third Five-Year Plan, but also the process by which it had been developed and thus the top party leaders who had formulated and approved it.

87

Next, Mao highlighted how planning should be anchored in the need to prepare for war. Such arguments were a cudgel for attacking what he viewed as revisionism within the party, including the flaws in central planning and complacency among local cadre.

88

Mao reminded his colleagues that “as

long as imperialism exists, there is a danger of war.”

89

He said that every coastal province should have ordnance factories, as these provinces could not wait for the second and third lines to supply them once a war started. Mao also said that every province should have their own first, second and third lines and urged that “every province should have some military industries to produce their own rifles, sub-machine guns, light and heavy machine guns, mortars, bullets and explosives. As long as we have these, we can relax.”

90

At the same time, Mao viewed local cadres as complacent, not interested in preparing for the worst. He complained that “now localities do not engage in military affairs” and then called for developing local armed forces (

difang budui

) in first- and second-line provinces.

91

Otherwise, “as soon as something happens, you will be unprepared.” Mao further chided the audience, stating that local cadre were less prepared than the Viet Cong, who were waging a guerrilla war in South Vietnam. He asked, “What happens when war erupts? When the enemy invades [

dajin

] our national territory? I dare to assert that it will not be like South Vietnam.” For Mao, the core of the problem was that “party committees in all localities cannot care only about civil affairs and not military ones, only care about money and not care about guns.”

92

Foreshadowing his emphasis on luring the enemy in deep, Mao noted that “as soon as fighting starts, prepare to smash [the enemy] to pieces, and prepare to abandon cities. Every province must have a solution.”

93

Mao’s concerns about revisionism within the CCP motivated his criticism of planning and local cadre. When Liu Shaoqi raised the subject of revisionism occurring in China, Mao said “it had already appeared.”

94

More ominously, again implicating local cadre, Mao warned that “a third of the power of the state is not in our hands, it is in the hands of the enemy.”

95

He then issued what Bo Yibo recalled as a solemn appeal: “Pass on [this message] all the way down to the county level: what if a Khrushchev-like figure emerges? What if there is revisionism at the center in China? County party committees must resist a revisionist center.”

96

Mao implied that localities must not only prepare to deal with an invasion, but also with a revisionist central leadership.

Deng Xiaoping later concluded that Mao’s decision to overturn economic policy in 1964 marked the start of the Cultural Revolution. Deng recalled that after the “defeat” of the Great Leap, Mao “rarely inquired about the economy” and focused on class struggle. But in 1964, Mao “scolded” Li Fuchun, Li Xiannian and Bo Yibo when he asked “why China was not developing the third line.” Deng noted that “China subsequently entered into a high tide of fervent development of the big and small third lines. I think the Cultural Revolution found its origin at that time.”

9

7

Adoption of the 1964 Strategic Guideline

At the end of the central work conference, Mao met with the Politburo Standing Committee and the first party secretaries of the CCP’s regional bureaus at the Ming Tombs outside Beijing. As Liu Ruiqing recalled, Mao in his remarks “negated” the existing strategic guideline of “resist in the north, open in the south.”

98

In its place, Mao called for a strategy based on preparing for an attack from any direction and abandoning a forward defense in favor of luring the enemy in deep. By increasing the importance of military affairs for local party committees, such a military strategy complemented Mao’s plans to decentralize economic planning and combat revisionism within the party bureaucracy.

MAO REJECTS THE EXISTING MILITARY STRATEGY

Several features of Mao’s speech highlight his domestic political motivations. To start, his concerns about the existing military strategy were not raised in a meeting of China’s senior military officers, such as a CMC meeting, or even during an informal gathering of senior generals, such as Lin Biao and Luo Ruiqing. Lin Biao, the ranking party member in charge of the PLA, was only briefed on Mao’s speech several weeks later.

99

Instead, Mao chose to challenge China’s existing military strategy before central and regional party leaders with little or no direct involvement in high-level military affairs. The choice of venue alone indicates that his comments on strategy were designed to bolster his political agenda, not China’s security. In addition, Mao’s remarks did not focus exclusively or primarily on military strategy. Instead, the two topics of his speech were the need for local party committees to “grasp” military affairs, and the question of leadership succession within the party—two areas at the fore of his concerns about revisionism.

The first part of Mao’s speech stressed again the need for local party committees to emphasize their work on military affairs. To do so, Mao questioned the primary strategic direction in the 1960 guideline. As noted earlier, he believed that local officials were lax and complacent. Identifying a general problem for local party leaders to solve would counter such complacency—in this case, their lack of preparations to conduct independent military operations in their areas if China was attacked. If China lacked a primary strategic direction and an attack could occur anywhere, then military affairs and preparing for war would be the responsibility of all local leaders, not just those in the likely area of a US attack in the north. The emphasis on independent operations also evoked the revolutionary spirit of the civil war, again reflecting Mao’s concerns about revisionism.

Mao began by stating that “local party committees need to work on military affairs.” For Mao, “just watching exercises is not enough.” He then stated that

all regions (

daqu

) and provinces “need to create a plan that includes working on the people’s militia and repairing machinery and munitions factories.” He placed the onus on provincial party committees, stating that they needed to “take an interest in the troops and militia within the provinces,” and further chided provincial first party secretaries, who were also political commissars, for shirking their responsibilities and being “phony commissars.”

Then Mao turned to the strategic guideline, which he said he “had thought about for long time.” He first questioned the primary strategic direction in the 1960 strategy, which had been premised on an attack occurring in the northeast, especially the Shandong Peninsula. Mao began by stating that “in the past, we have discussed resisting in the north and opening in the south. My view is, not necessarily.”

100

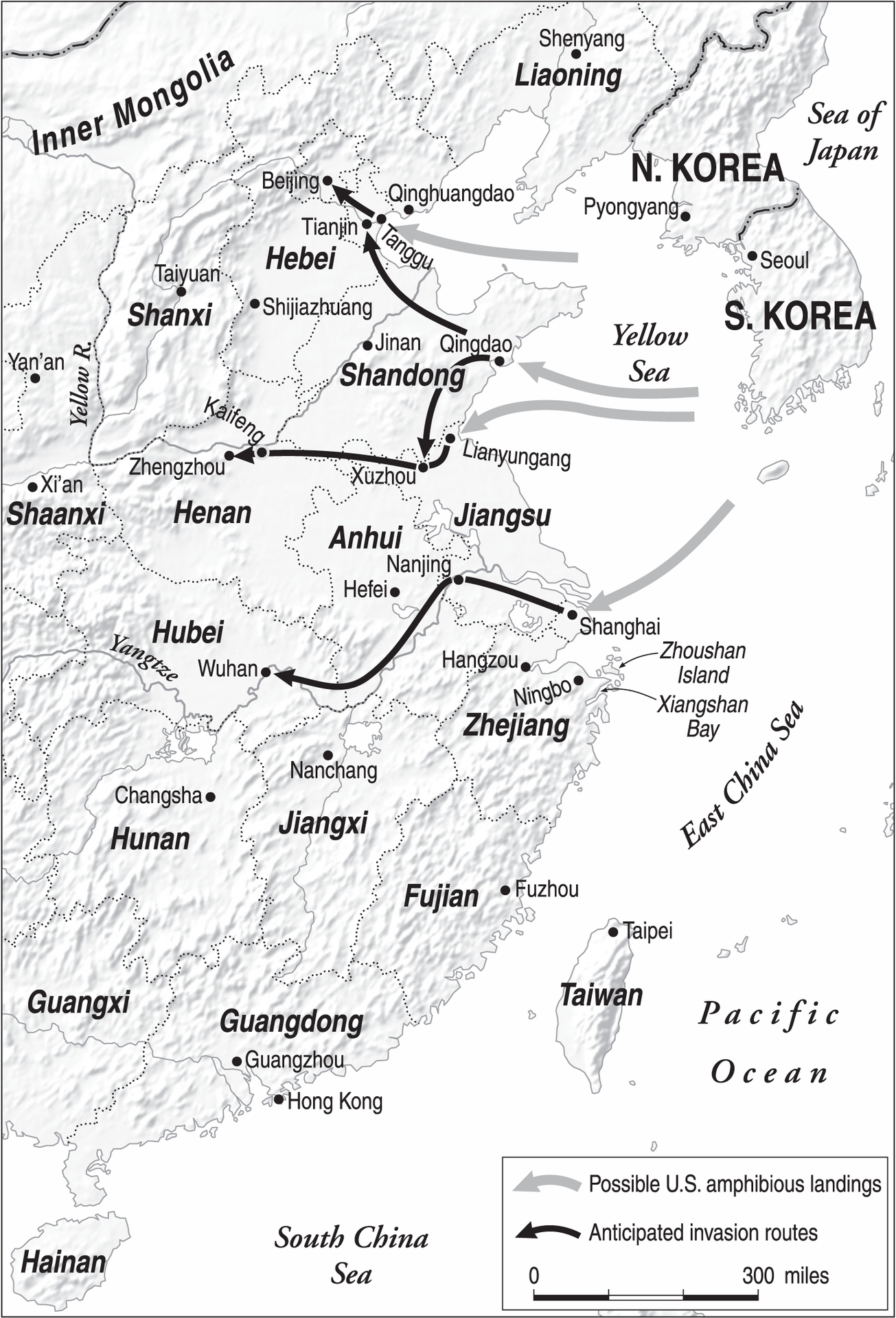

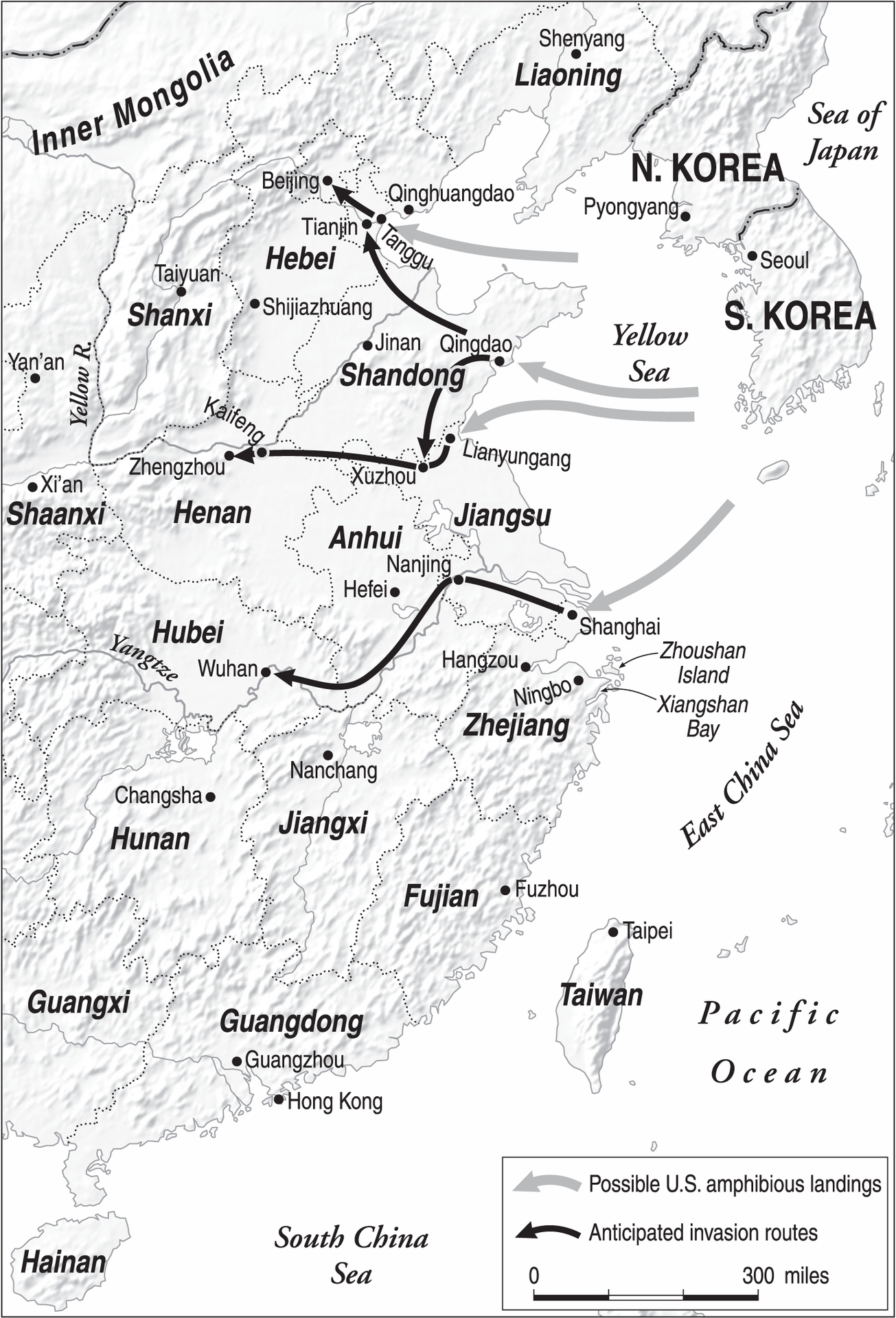

Mao then asked whether the enemy would “necessarily have to come from the northeast.” After dismissing the possibility of an attack from the southwest through Guangxi, he then raised alternative directions of attack. As shown in

map 4.1

, these included landing at Tanggu in the Bohai Gulf to occupy Tianjin and Beijing; landing at Qingdao to occupy Tianjin or Xuzhou; landing at Lianyungang to advance onto Xuzhou, Kaifeng, and Zhengzhou; or landing at Shanghai to take Nanjing and Wuhan. His larger point was the danger of focusing on a singular strategic direction, as “it is possible that the enemy may come in from any of these places.”

Mao then questioned the second component of the 1960 strategy, the basic guiding thought of “resisting” (

ding

) an invasion by defending fixed positions. Against invoking the revolutionary period, Mao said that “we can still use the old way of fighting,” the combination of fighting and moving at the heart of mobile warfare. Invoking language from his 1936 lecture on military strategy in the revolution, he stated: “Fight if you can fight and win, and move when you cannot fight and win.” More generally, he asserted that it would be unacceptable “to consider action based entirely on being able to resist the enemy.” Thus, for Mao, “considerations must be based on the inability to resist the enemy. If you can’t resist the enemy, it’s better to go!” Any member of the audience would understand that Mao was signaling his preference for luring the enemy in deep and mobile warfare.

Mao used these critiques of the existing strategy to argue that each province, county, and prefecture should develop its own militia and local forces that would be able to conduct independent operations in a major war. If a war broke out, he instructed, “Do not rely on the central government; do not rely on only the few millions of the People’s Liberation Army. In a country of this size, with a battlefront this long, it is insufficient to just rely on the People’s Liberation Army.” Again underscoring the need for self-reliance, local officials would be responsible for the defense of their own territory. Mao once more chastised them, stating that “there must be preparation. You people here only demand money, not guns.” He also called on the provinces to build their

military factories. For Mao, “it will be too late to do so once the fighting starts and you are cut off.

”

MAP 4.1.

Mao Zedong’s view of possible invasion routes (June 1964)

The second part of Mao’s speech focused on the need to select successors, foreshadowing the ninth open letter to the Soviet Union that would be published in July. Mao linked “preventing revisionism” with the questions of “selecting successors” in the party. He called for the need to select successors at all levels, including the center, provinces, prefectures, and counties—a task that he also assigned to party secretaries. He then outlined several ways to avoid revisionism in the next generation of leaders, such as practicing Marxism-Leninism, focusing on serving the majority of people and not a few, uniting with the majority of people, adopting a democratic work style, and conducting self-criticisms when making mistakes.

101

Afterward, Mao continued to stress themes mentioned in his June 16 speech. On July 2, he broadened the scope of his concern to include the Soviet Union, though he would still focus primarily on the United States for the next few years. Mao noted that “you cannot only pay attention to the east and not the north, only to imperialism and not revisionism.” He then emphasized again the need for all provinces to build their own munitions factories. Furthermore, “if problems arise,” such as a war, “the provinces are in charge of themselves” and “cannot rely on the center and the CMC” because “the center cannot take care of this.” Finally, Mao also underscored what appeared to be at least part of his motivation for using military preparations to counter revisionism: “If everything is prepared well, the enemy may not come, but if it is not prepared well, the enemy may come.”

102

On July 15, Mao again hinted at luring in deep as the basic guiding thought for operations. As he told Zhou Enlai, “Our way of fighting [

dafa

] is that if ‘I’ can defeat ‘you,’ then I will defeat you. When I cannot defeat you, then I won’t allow you to defeat me. If the opportunity is not ripe, our main forces will not fight with you desperately, but will maintain their distance. Until the time when we can wipe you out, we will annihilate you. Little by little, you will be defeated.”

103

Mao also said, “If Beijing is lost, it is not critical” and that party leaders “will go to caves in the mountains between Beijing and Taiyuan and struggle with the enemy there.”

104

He stressed again the development of local forces and the importance of being able to conduct independent operations, suggesting that eleven or twelve divisions be sent to coastal and border provinces to develop and train militias to carry out these operations.

105

For Mao, in the upcoming war, “these divisions would form the backbone” of any resistance.

106

USING THE THIRD LINE TO ATTACK CENTRAL PLANNING

As Mao rejected the existing military strategy, he continued his attack on China’s central planning apparatus. After Mao’s initial interventions in May 1964,

Li Fuchun began to study how to enact Mao’s instructions for the third line. In the middle of June, teams from the State Planning Commission visited various locations that would become part of the third line. Nevertheless, putting Mao’s ambitious plan into practice was challenging. For example, during the planning process, a dispute arose over where to site the Panzhihua steel mill. Local officials from the Southwest Bureau and the Sichuan party committee believed the proposed location was too remote and inhospitable, contradicting officials from the State Planning Commission seeking to enact Mao’s wishes.

107

By mid-August, Mao had become “greatly dissatisfied” with the pace of plans for developing the third line. He asked Li Fuchun, “Why is the third line construction so slow?”

108

Li replied as one might expect an economic planner to reply, stating that the conditions surrounding Panzhihua were complicated, that that China lacked funds, and that formulating an investment plan would require additional meetings and analysis. Although Li’s response was reasonable, Mao blamed the State Planning Commission. He then charged that its methods of planning were “inappropriate” and that its work was “ineffective.”

109

Mao’s criticisms reflected his dissatisfaction with the Soviet-style planning process that it was designed to execute, and the party bureaucracy more generally.

At the annual Beidaihe leadership retreat in early August, criticism of the State Planning Commission mounted. Mao’s surrogate on the commission, Deputy Director Chen Boda, attacked it for its “procrastinating and lax work style.”

110

Chen echoed Mao by alleging that the commission’s Soviet-style “management system helped revisionism grow.”

111

Mao then instructed that Chen’s views be distributed to all local party committees and be placed on the agenda for the upcoming central work conference in October. Mao included his own criticism of the commission, leaving no doubt about his intentions. He declared that “the method of planning work must change within the next two years. If they do not change, it would be better to eliminate the planning commission and replace it with another body.”

112

At the end of the month, Mao even criticized the State Planning Commission for not “reporting their work” (

huibao gongzuo

) and “blocking” (

fengsuo

) him and Liu Shaoqi.

113

Given that many members of the State Planning Commission’s leadership were also part of the Central Committee’s Secretariat, Mao’s claim was disingenuous, but it did reflect his dissatisfaction with the front-line leadership of the party.

In mid-August, the pace of efforts to develop the third line accelerated. Mao commented on a GSD report written in April 1964, which had outlined the high concentration of people, infrastructure, and industry in coastal provinces that would be vulnerable to an attack in a war.

b

Mao’s comments led to the

formation of a leading small group, headed by Li Fuchun, to oversee drafting of plans for developing the third line. More broadly, Mao also began to push for decentralization in economic decision-making. In his study of China’s economy during this period, Barry Naughton concludes that economic decentralization and the third line development were “complementary.”

114

In September 1964, local governments were authorized to control output from smaller factories and to hire temporary workers, thereby allowing localities to “run truly autonomous industrial systems.”

115

The role of the State Planning Commission was limited in favor of the empowering the provinces and multiprovince economic regions, who were encouraged to be more self-reliant and responsible for economic development within their own areas. Thus, the development of the third line, justified by an ambiguous threat, helped Mao to weaken a core pillar of the bureaucracy, which he associated with revisionism.

In December, Mao completed his attack on the State Planning Commission when he removed Li Fuchun, its director, from daily work. Mao had Yu Qiuli transferred from the Daqing oil field to serve as deputy director and party secretary of the State Planning Commission. Yu served as a political commissar in the First Field Army during the civil war and, in 1958, became minister of petroleum in charge of developing the Daqing oil field in Heilongjiang province. Yu formed a group within the State Planning Commission that became known as the “little planning commission” (

xiao jiwei

), which reported directly to Mao and subverted existing party channels. It oversaw the drafting of the Third Five-Year Plan that would be keyed to the third line development and an economy that would be geared to preparing for war.

116

Mao had regained control.

EXTERNAL THREATS?

The conventional explanation for Mao’s desire to develop the third line, and to change China’s military strategy in 1964, emphasizes external threats, especially the US escalation of the war in Vietnam. Nevertheless, although external security concerns may have been part of Mao’s calculus, they offer a weak explanation for Mao’s decisions regarding economic policy and military strategy for several reasons.

First, although China had experienced heightened insecurity in 1962, China’s external environment had stabilized by 1963. After its defeat in 1962, India refrained from challenging China’s control of the border. Following the aborted effort to attack the mainland in June 1962, the Nationalists focused on small-scale coastal raids, most of which were easily defeated.

117

Toward the south, the United States had escalated its commitment to defending South Vietnam since 1962, dispatching an increasing number of advisors. Yet there were no indications in the spring of 1964 that the United States was planning to escalate the

war to include attacks on North Vietnam or the deployment of combat forces in South Vietnam.

118

Finally, after the 1962 YiTa Incident in Xinjiang revealed China’s inability to secure its borders against the Soviet Union, China had begun to rectify its weak border defenses in the northwest.

119

Nevertheless, in early 1964, Moscow had not yet started to increase the number of forces along China’s northern border; this would begin at the very end of 1965.

120

Moreover, throughout the first half of 1964, Beijing and Moscow held substantive negotiations on their disputed border, reaching a consensus on how to delimit the eastern sector.

121

Although Soviet-Chinese ties were poor, armed conflict was far from imminent. Chinese military planners studied how to improve border security, but primarily to rectify the lack of any defenses in the 1950s rather than to prepare to defend against a major attack.

122

Finally, when Mao pushed for the third line, China was on the cusp of exploding its first atomic device in October, a development that should have allayed concerns about growing external threats.

Second, Mao’s push for the third line and rejection of the existing military strategy occurred three months before the Gulf of Tonkin Incident in early August 1964. Thus, US escalation of the war in Vietnam cannot explain the change in Mao’s approach to either economic policy or military strategy.

123

A week before Mao rejected the existing strategy in June, he did not view a US attack as imminent, stating that “we are not the chief of staff of the United States. We do not know when he will fight.”

124

Even the Gulf of Tonkin incident in early August did not alter Mao’s assessment of the likelihood of a conflict with the United States. During a meeting with the Vietnamese leader Le Duan on August 13, for example, when commenting on the US bombing of North Vietnam after Tonkin, Mao observed that “America has not sent ground forces.” He concluded that “it appears that America does not want to fight, you do not want to fight, we do not want to fight.”

125

Third, Mao appeared to reject the most likely way in which the United States and China might clash. In his June speech, he downplayed the possibility of a US attack in southern China along the border with Vietnam and said that “even if the enemy comes through Guangxi and Guangdong? He could fight into Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan, but he wouldn’t obtain anything.”

126

In both this speech and in remarks in November 1965, after the United States had escalated the war in South Vietnam, Mao continued to emphasize different points of attack along the coast. In other words, he did not propose reorienting China’s strategy to address the most likely scenario and instead continued to underscore that the direction was unclear. External threats cannot account for this aspect of Mao’s thinking, but internal threats and revisionism can. Focusing on wide possibilities along the coast allowed Mao to magnify the threat that China faced, justifying the development of the third line and the shift in strategy to luring the enemy in deep

.

Fourth, when Mao discussed external threats in May and June 1964, he described them vaguely and without urgency. He did not appear to believe that China would be attacked immediately, except for a brief period in the spring of 1965, as discussed below.

127

Mao’s statement in May 1964 to guard against a surprise attack repeated almost verbatim a similar remark from 1955.

128

Both remarks reflected ongoing hostility between the United States and China rather than an imminent threat. In early July 1964, Liu Shaoqi, summarizing Mao’s remarks from the central work conference, did not convey any sense of urgency. Liu said that “we have not yet seen the sign of when the imperialists plan to attack, but we must prepare and every day be alert to the presence of the enemy.”

129

Finally, in mid-July 1965, Luo Ruiqing summarized his understanding of Mao’s comments on strategy as “thinking of things as if they were more difficult, and taking into consideration all possible difficulties.”

130

Fifth, the plans for developing the third line in the fall of 1964 did not reflect a sense of urgency that would be associated with an increased external threat. At this point, plans for the third line were as much about industrial development as specific defense industries and war preparations. The main projects Mao identified, for example, were steel mills, other basic industries, and railway networks. These projects were capital-intensive efforts with long lead times of seven to ten years, reinforcing the emphasis on industry over agriculture in economic policy and the general lack of urgency. If these projects were necessary for China to defend itself in the way Mao imagined, then their long lead times implied that a major war was not imminent. But these projects were necessary for weakening the party bureaucracy and enabling self-reliance.

U.S. ESCALATION IN VIETNAM

The escalation of the war in Vietnam in 1965 created an opportunity for China to reconsider US threats. The prospect of escalation provided an opportunity for Mao to reemphasize many of the ideas he had raised since June 1964, including his general exhortation of “preparing for the worst.” Yet when the US threat abated in June 1965, he continued to press ahead with his new economic policy and military strategy, becoming much more explicit about the role of luring the enemy in deep. Mao’s emphasis on luring in deep after the US threat receded is consistent with his domestic motivations to change China’s military strategy in June 1964.

At the start of 1965, Chinese leaders did not perceive an increased threat from the United States. On January 9, during an interview with the American journalist Edgar Snow, Mao sounded relatively optimistic. In response to Snow’s statement that a major war would not occur between China and the United States, Mao concurred, replying, “It may be that you are right.”

131

He also noted Secretary of State Dean Rusk’s comment that the United States

would not escalate the war in South Vietnam to the North, thereby precluding the possibility of a direct US-China conflict.

132

At the same time, the CMC issued a directive instructing Chinese pilots to avoid direct engagements with aircraft from United States that entered into Chinese airspace.

133

In February 1965, the Viet Cong attacked a US Army helicopter base at Pleiku in South Vietnam. The immediate US response was to conduct several bombing campaigns against the North. The strategic response was the decision to deploy combat forces, which began in early March, when two Marine battalions landed in Danang and would grow to over eighty thousand by June 1965.

134

Following the initial US deployment of combat troops, North Vietnam dispatched a delegation to Beijing to seek greater support from China. This request prompted China’s top leaders to make a series of decisions about their involvement in the Vietnam War that offers an opportunity to examine how a significant increase in threat—the prospect that the war would escalate to China’s border—influenced thinking on military strategy.

First, over the next few months, China agreed to provide Vietnam with military support. Although China did not provide the pilots that Vietnam requested, by June 1965 China began to dispatch air defense, engineering, logistics, and others troops to Vietnam. Between June 1965 and March 1968, China would send a total of 320,000 troops.

135

Second, China decided to signal its resolve to the United States to deter any expansion of the war in Vietnam to China’s border or within China. This started with “militant” articles in outlets like the

People’s Daily

. In early April, while in Karachi, Zhou Enlai asked Pakistani President Ayub Khan to send a message to Washington. The essence of the message was that China would not initiate or provoke a conflict with the United States, but would fiercely resist “should the United States impose a war on China.”

136

After Khan’s trip to the United States was postponed in mid-April, China asked the British chargé d’affairs in Beijing to pass along the same message, which took place in Washington on June 2.

137

Mao also authorized a change in the rules of engagement after US intrusions in the airspace over Hainan Island on April 8 and 9, stating that China “should resolutely attack” such aircraft.

138

On April 12, the

People’s Daily

carried a strongly worded editorial about the encounters consistent with this change.

139

Third, Mao instructed that China undertake a domestic mobilization. As Mao had explained at the end of March, domestic mobilization “displays strength [

shiwei

] to the enemy, supports Vietnam, and promotes all aspects of our work.”

140

Reflecting his preference for worst-case planning, Mao concluded that China “must prepare to fight this year, next year, the following year.”

141

Even with the heightened level of threat and uncertainty about US escalation, Mao’s comment that mobilization would help “all aspects of our work” also points to the domestic imperative behind his effort to change strategy. On April 12, a full meeting of the Politburo was held to discuss the

mobilization. At the meeting, Deng Xiaoping stated that “the scope of the war could expand” to include Chinese territory along the border with Vietnam or even a larger scale limited war with the United States.”

142

This period in early April likely represents the peak of Chinese concerns about US escalation. Nevertheless, China had not yet mobilized PLA units or localities to counter a potential US attack, unlike the preparations to counter a Nationalist attack in May and June 1962.

On April 12, the Central Committee issued instructions for strengthening war preparations. The document noted that the US expansion of the war in Vietnam “directly threatens our security” and that China “must prepare for the United States to bring the flames of war to our homeland.” Reflecting the uncertainty over the future of the war that Deng had raised, the instructions also noted that China “must be prepared for a small, medium or even large war.” They also highlighted China’s vulnerability to aerial attacks and the need to defend major military facilities, industrial bases, transportation nodes, strategic areas (

yaodi

) and cities.

143

Ironically, the document echoed many of the reasons why Mao had pushed for the development of the third line a year earlier, when there was no imminent threat of the United States expanding the war.

Fourth, the PLA held an army-wide operations meeting, which lasted for about six weeks. In the early 1960s, the PLA convened such army-wide operations meetings every spring, in either March or April.

144

The purpose of this particular meeting was to discuss Mao’s various instructions on military strategy since his June 1964 speech to “unify thinking” and then draft army-wide operations and combat readiness (

zhanbei

) plans.

145

As Luo Ruiqing recalled, “This operations meeting specifically discussed implementing the strategic guideline instructed by the chairman.”

146

Although the discussion was no doubt colored by concerns about US escalation of the war in Vietnam, the meeting was not convened for this reason, and the question of how to respond to this contingency does not appear to have been its main focus. For example, when a document distributed during the meeting suggested that the United States would attack China through Guangxi province, which is adjacent to Vietnam, Luo criticized it for contradicting Mao’s comment in June 1964 that the area of attack was uncertain and would not necessarily come from this direction.

147

The meeting also stated that although the PLA should be rooted in preparing for the worst case, China was not facing “imminent danger or in a desperate situation [

jiji kewei buke zhongri

].”

148

In late April, senior military officers briefed Mao on the army-wide operations meeting. In his response, Mao emphasized themes that he had already introduced in 1964. On the one hand, he agreed with building three defensive layers and not allowing the “enemy” to “drive straight in,” as in Germany’s invasion of Russia. On the other hand, he also underscored the importance of not holding territory for “too long.” For Mao, the only purpose of a fixed defense

was to buy time to mobilize. Afterward, he said, “let him in, lure the enemy in deep and afterwards annihilate him.” Mao also indicated that he did not believe that China faced an immediate threat from the United States. He described the United States as an “opportunist” and “not that adventurous,” asserting that the United States had entered World War I and World War II only after other states had done most of the fighting.

149

The clear implication was that Mao did not believe a US attack on China was imminent.

The party leadership’s instructions to the army-wide operations meeting were also consistent with Mao’s views on strategy. On May 19, top party leaders attended the operations meeting, including Liu Shaoqi, Zhou Enlai, Zhu De, Lin Biao, and Deng Xiaoping. All issued instructions that did not reflect a concern about an immediate threat. The leaders noted that China should “prepare for an early war, a large-scale war and fighting enemies on all sides.” Such preparations were viewed as key to delaying or even preventing a war because “as long as we are well prepared, enemies will not initiate conflicts easily.” The leaders nevertheless cautioned against significantly increasing force levels, noting that “if we spend too many resources and too much effort on the military, national economic development will be affected.”

150

CONSOLIDATING LURING THE ENEMY IN DEEP

On June 7, the British chargé d’affairs in Beijing informed the foreign ministry that China’s warning had been transmitted to Secretary of State Dean Rusk. Combined with US statements about limiting its combat operations to South Vietnam, the threat of expansion of the war in Vietnam had receded. Nevertheless, Mao continued to emphasize the change in China’s military strategy he made a year earlier by underscoring the role of luring the enemy in deep over a fixed, forward defense.

The occasion for Mao’s remarks was a debate over the appropriate force posture along the east coast during a meeting of party leaders in Hangzhou on June 16, 1965. The exchange itself indicated that the PLA had not yet “unified thought” on China’s military strategy, despite Mao’s previous instructions and remarks. Xu Shiyou, commander of the Nanjing Military Region, advocated for “completely resisting the enemy”: defeating him on the coast and not allowing him to “come in.”

151

Xu echoed the strategy of forward defense, which he had used to prepare to defend the region since the mid-1950s.

152

Mao responded by arguing for luring the enemy in deep, stating that “if you don’t give the enemy a slight advantage, giving him a taste of victory, then that just won’t do because he won’t come in. He will only come in when you let him feel a taste of victory.” He then suggested that China “prepare to give the enemy Shanghai, Suzhou, Nanjing, Huangshi, and Wuhan. This way our forces can spread out [

baikai

] and fight victoriously.”

15

3

Mao’s remarks are revealing. First and foremost, by mid-June, the threat of conflict with the United States on China’s border adjacent to Vietnam had abated. Zhou’s warning to the United States had been delivered by the United Kingdom, allaying Chinese fears.

154

The United States indicated that it would not expand the war to North Vietnam or beyond. Mao emphasized luring the enemy in deep when the threat of conflict with the United States decreased. Moreover, he continued to push for luring in deep throughout the second half of 1965, which is consistent with the political logic outlined above but inconsistent with China’s assessment of the situation it faced in Vietnam. Likewise, Mao’s June remarks in Hangzhou contained no reference to the situation in Vietnam. Nor did Luo Ruiqing’s summary of Mao’s thinking on military strategy delivered a few weeks later.

155

Second, Mao’s emphasis on luring the enemy in deep revealed his desire for a decisive and total victory over the United States. Mao did not emphasize luring in deep because it provided a better way to defend China. He preferred luring in deep because it was the only way for China to fight a “war of annihilation” (

jianmie zhan

) that would produce a decisive victory, which would presumably enhance Mao’s reputation at home and within the socialist bloc. Such an approach would also complement efforts to decentralize decision-making power and weaken the party’s central bureaucracy. Mao believed that a protracted war inside China would create conditions for a decisive victory when compared with more limited operations to prevent the United States from seizing territory. As he noted, “I simply worry that the enemy won’t come in and that he’ll only fight a little on the border … the enemy can only be fought well when he is lured deep into home territory.”

156

Later Mao was more explicit, noting that “you can’t catch fish without bait.”

157

He also partly contradicted himself by stating that if China prepared sufficiently for war, then the enemy would not attack. Nevertheless, he still preferred to prepare to fight a protracted war on Chinese territory that might hold the promise of a decisive victory versus more limited operations to prevent an enemy from seizing any territory.

Third, Mao preferred luring in deep because of the domestic political benefits for countering revisionism and continuing class struggle. For Mao, “if the enemy really will not come, that’s actually a bad thing.” He reasoned that, without an invasion, the masses would not gain any experience and “bad” elements in society would not be “differentiated [

budao fenhua

],” such as landlords, rich peasants, and counterrevolutionaries. Moreover, “the enemy will not be exposed”—by implication, Mao’s domestic enemies and not China’s foreign ones.

158

The domestic political benefits of a strategy of luring the enemy in deep explains why strategic retreat was more important than stopping an invasion. Because preparing to lure the enemy in deep would further administrative decentralization from the center to localities, general war preparations would