5

The 1980 Strategy: “Active Defense”

In September 1980, the General Staff Department (GSD) convened a month-long meeting of senior officers to discuss how to counter an attack by the Soviet Union. The meeting’s purpose was to determine what principles should guide PLA operations during the initial phase of such a war. At the end of the meeting, the CMC approved a new strategic guideline known simply as “active defense.” In contrast to the existing strategic guideline, which stressed luring the enemy in deep, the new strategy called for the PLA to resist a Soviet invasion and prevent a Soviet breakthrough using a forward defense anchored around positional warfare.

The adoption of the 1980 strategic guideline, which represents the second of the three major changes in China’s military strategy, is puzzling. China had faced a clear military threat from the Soviet Union for over a decade. In 1966, the Soviet Union signed a defense treaty with Mongolia and began to increase the number of troops deployed along China’s northern border. Following the March 1969 clash between Chinese and Soviet forces at Zhenbao (Damansky) Island, the Soviet threat continued to grow, with fifty divisions facing China by 1979. Nevertheless, despite this threat, China did not adopt a new military strategy until 1980. The onset of the Soviet military threat alone did not prompt China to change its military strategy.

Apart from the Soviet threat, two other factors are central to understanding when, why, and how China changed its military strategy in 1980. First, an important motivation was an assessment of a significant shift in the conduct of warfare that would characterize Soviet operations in an invasion of China. This assessment was based on observations of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, in

which clients of the United States and the Soviet Union employed advanced weapons in new ways. PLA strategists such as Su Yu and Song Shilun, among others, believed that a significant shift in the conduct of warfare had occurred that would place China in an even more disadvantageous position should conflict erupt with the Soviet Union. The content of the 1980 strategic guideline reflected an effort to counter a Soviet threat that would be characterized by new ways of warfare.

Second, a split at the highest levels of the CCP prevented the PLA from responding to the Soviet threat. Throughout the Cultural Revolution, the CCP elite was fractured, as different groups competed for power. After Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, the party lacked a clear consensus on the structure of authority. Hua Guofeng, who was anointed as Mao’s successor months before Mao’s death, held the top positions in the party, state, and military. After Deng Xiaoping returned to work in 1977, he would spend the next few years displacing Hua and consolidating his position as China’s paramount leader. After party unity was restored, the PLA was able to pursue a major change in strategy.

The adoption of the 1980 strategic guideline is illuminating for several reasons. Previously, Western analysts have often described China’s strategy during this period as “people’s war under modern conditions,” which implies continuity with Maoist approaches.

1

Although some senior officers used this phrase in their speeches, it was not part of the formulation of the new strategy. Instead, it only reflected the view that any war with the Soviet Union on China’s territory would be a protracted one, given the gap in Soviet and Chinese capabilities. The phrase did not describe how such a war would be waged or what forces would be required. Following the death of Mao, references to people’s war also likely maintained superficial ideological continuity, despite the significant changes in operations in the new guideline that rejected Mao’s idea of luring the enemy in deep.

The examination of the 1980 strategic guideline also clarifies the relationship between China’s military strategy and the “strategic transformation” in army building that was announced along with the reduction of one million soldiers in 1985. The strategic transformation did not signal the adoption of a new military strategy. Instead, it refers to Deng Xiaoping’s judgment that China would not face a total war for one or two decades and thus could shift from a “war footing” posture to peacetime military modernization. Moreover, the 1985 force reduction represents the continuation of downsizings in 1980 and 1982 to improve the quality and effectiveness of the force under the 1980 strategy. The strategic transformation did not outline what kind of wars the PLA should prepare to fight or how it should prepare to fight them.

This chapter unfolds in seven parts. The first section demonstrates that the strategic guideline adopted in 1980 represents a major change in China’s military strategy. The next section shows that senior military officers perceived a

significant shift in the conduct of warfare, which served as the external stimulus for the adoption of a new strategy in addition to the Soviet threat. As the third section demonstrates, however, the PLA’s high command could only act on these shifts in the conduct of warfare once political unity after Mao’s death had been restored following Deng’s consolidation of political power in 1979 and 1980. The next two sections examine the adoption and implementation of the new strategy, while the final two sections review the 1985 downsizing and adoption of the 1988 strategic guideline.

“Active Defense”

The strategic guideline adopted during the September 1980 meeting of senior officers represents the second major change in China’s military strategy since 1949. The 1980 guideline, known simply as “active defense,” outlined a strategy to counter a Soviet invasion and prevent a strategic breakthrough. It represented a clear rejection of the existing strategy from the mid-1960s based on luring the enemy in deep and strategic retreat. Instead, similar to the 1956 strategy, the 1980 strategic guideline envisioned a forward defense that would be based on positional warfare and supplemented by small-scale mobile warfare. Such a strategy required that the PLA develop the ability to conduct combined arms operations to coordinate tank, artillery, and infantry units, deployed in a layered defensive network of fixed positions.

OVERVIEW OF THE 1980 STRATEGY

In the 1980 strategic guideline, the “basis of preparations for military struggle” was a surprise attack by the Soviet Union. The primary strategic direction was China’s northern border, also known as the “three norths” or the area from Heilongjiang province in the east to Xinjiang in the west.

2

Following the 1969 clash with the Soviets over Zhenbao Island, the situation on China’s northern border deteriorated, raising the prospect of a major war with Moscow.

3

Although the major Soviet attack that China’s leaders had feared in the fall of 1969 did not occur, the Soviet military threat grew throughout the decade. By 1979, the number of Soviet divisions along China’s northern border had increased from thirty-one to fifty.

4

Concerns about Soviet intentions intensified when Moscow signed a defense treaty with Vietnam in November 1978 and invaded Afghanistan in December 1979. Chinese strategists believed that a Soviet attack would involve tank columns conducting rapid, deep strikes, along with airborne operations in rear areas, to seek a swift and decisive victory.

5

The 1980 strategy was a strategy of strategic defense. It described how China would respond once the Soviet Union had invaded. The core of the 1980 strategy was a forward defense of China’s northern border, especially

potential invasion routes through Zhangjiakou or Jiayuguan, to prevent any strategic breakthrough and buy time for a nationwide mobilization. Afterward, the strategy called for combining the defense of strategic interior lines with offensive campaigns and operations on exterior lines to create a stalemate. Finally, if the effective strength of the invading force was sufficiently weakened, the PLA would shift to a strategic counterattack.

6

Although the new strategy altered how China would respond to an invasion, it remained based on waging a protracted war with the Soviet Union. A forward defense, rather than retreat, was viewed as key to victory in such a conflict.

The 1980 strategy excluded preempting a Soviet attack. The PLA lacked any credible means to launch strikes beyond its borders. Consistent with the principle of “gaining control by striking afterwards” or counterattacking (

houfa zhiren

), China would use force only after a Soviet invasion had started. In the initial phase, the role of offensive operations would be limited to small-scale mobile operations from fixed positions, especially along Soviet flanks. Once a strategic stalemate had occurred, offensive operations would play a central role in expelling the invading force. The role of nuclear weapons, which China now possessed, was also limited to defensive uses. Despite the potential of using nuclear weapons as a form of “invasion insurance,” China’s strategy envisioned their use only in response to a nuclear attack on China, including the use of tactical nuclear weapons by the Soviets. Although China researched the neutron bomb in the early 1980s, it did not ultimately decide to develop and deploy such weapons, nor did it alter its approach to nuclear weapons under the 1980 strategic guideline.

7

OPERATIONAL DOCTRINE

A key component of any strategic guideline is the identification of the “form of operations” that the PLA should be prepared to conduct in the future. In contrast to the centrality of mobile and guerrilla warfare in luring the enemy in deep, the 1980 strategy identified positional warfare as the main form of operations for the PLA or “positional warfare of fixed defense” (

jianshou fangyu de zhendizhan

).

8

By rejecting luring in deep as the basis for China’s strategy, senior military officers downplayed the role of mobile warfare at the strategic level. Instead, the 1980 guideline envisioned creating a layered, in-depth network of defensive positions, each of which an invader would need to destroy.

The “basic guiding thought for operations” was the way in which positional, mobile, and guerrilla warfare would be combined. In the initial phase of a war, positional warfare would occur in forward areas between China’s main population areas and its international frontiers. The new strategic guideline limited the role of mobile warfare to small and medium-sized offensive

operations close to the defensive positions that the PLA would try to hold. Nevertheless, the main goal of the strategy was to resist a Soviet attack as long as possible, to create a stalemate and buy time to mobilize forces.

9

Guerrilla warfare would be limited to those areas that China would be unable to defend in the initial phase of a war, such as parts of Xinjiang.

Successful positional warfare required developing combined arms capabilities for both defensive and offensive operations. Although the 1956 strategic guideline envisioned creating such a capability, this goal was never achieved because of Mao’s decision to pursue luring the enemy in deep and its emphasis on the dispersion of forces and independent operations. China’s 1979 invasion of Vietnam revealed the PLA’s inability to conduct combined arms operations, even though the war itself was not a primary factor in the adoption of the new strategy.

10

To develop such a capability, the PLA started to draft the “third generation” of combat regulations in 1982, which were finished in 1987.

11

Similarly, the drafting of the

Science of Campaigns Outline

, the PLA’s first text on the operational level of war, restarted in the early 1980s and was published in 1987, along with the first edition of the

Science of Military Strategy

.

12

FORCE STRUCTURE

The 1980 strategic guideline required China to develop a more nimble and effective force. When the strategy was adopted, the PLA had roughly six million soldiers. As early as 1975, Deng Xiaoping as chief of the general staff had criticized the PLA as “bloated” because of the rapid growth in the number of officers and noncombat troops in the late 1960s. Following the adoption of the 1980 strategic guideline, three major force reductions were undertaken to improve the flexibility of command and overall effectiveness of the force while also reducing the defense burden on a national economy now focused on reform and opening. The first two reductions occurred in 1980 and 1982, in which roughly two million soldiers were cut. Planning for the third reduction of one million troops began in early 1984 and was announced in June 1985, bringing the total size of the force to 3.2 million when it was completed in 1987.

13

The 1985 reduction was part of a much broader reorganization of the force, including the consolidation of eleven military regions into seven and the transformation of thirty-five armies into twenty-four combined arms group armies in addition to the reduction and streamlining of headquarters and command departments.

14

Changes in force structure were also pursued to enhance the PLA’s ability to conduct combined arms operations. One of the topics discussed at the 1980 seminar to adopt the new strategic guideline was the importance of creating a “combined force” (

hecheng jundui

) that would be able to conduct combined arms operations. The PLA decided to experiment with transforming armies

into combined arms group armies composed of infantry, artillery, tank, rocket, and antiaircraft artillery units. These would be used as a mobile reserve force (

yubei dui

) that would be deployed in the direction of the Soviet attack to prevent a breakthrough. In early 1981, the CMC decided to form two units on a trial basis.

15

Pilot units were created in 1983 and by 1985 all armies (

jun

) had been converted into combined arms group armies as part of the 1985 force reduction.

TRAINING

All aspects of education and training changed under the 1980 strategic guideline. In October 1980, the general departments issued a sweeping plan to reopen and revitalize military academies, which had ceased to function effectively during the Cultural Revolution and were ill suited to training soldiers to conduct the complex military operations that the new strategy required.

16

In November 1980, the PLA held an army-wide training meeting, which identified “coordinated operations” (

xietong zuozhan

)— essentially combined arms operations—as the focus for future training of the force.

17

In February 1981, the GSD issued a new training program that provided a new framework for all aspects of training, with an emphasis on combined arms operations.

18

Along with changes to education, the PLA increased the scope and tempo of military exercises. The renewed emphasis on exercises and training was symbolized by an exercise held in the Beijing Military Region in September 1981. Dubbed the “802” meeting, it represented the PLA’s largest exercise since 1949 and involved more than 110,000 troops from eight divisions. The purpose was to explore defensive operations during the initial phase of a Soviet invasion and thereby “concretize the strategic guideline.”

19

Afterward, other military regions as well as the services began to hold larger and more realistic exercises, in stark contrast to the 1970s, when small-scale exercises were held sporadically, if at all, reflecting a much higher degree of professionalism with the force.

The 1973 Arab-Israeli War and the Conduct of Warfare

Throughout the 1970s, China faced a clear and growing threat from the Soviets, but did not alter its military strategy of luring the enemy in deep for a decade. Nevertheless, by the mid-1970s, senior PLA officers began to reconsider China’s approach for countering the Soviet threat and to advocate for changing China’s military strategy. These assessments were based on shifts in the conduct of warfare that were seen as characterizing how the Soviets would fight, especially the increased speed and lethality of modern military operations involving armored forces and airpower

.

SU YU’S CRITIQUES OF LURING THE ENEMY IN DEEP

Su Yu, the chief of staff from the 1950s, was the earliest and most prominent advocate for changing China’s strategy. In 1972, after the death of Lin Biao, Su Yu had returned from working in the State Council on government affairs to serve as the commissar and party secretary of the Academy of Military Science (AMS). Su was worried. From his perspective, the PLA in the Cultural Revolution had failed to study how to fight future wars and ignored foreign technological developments that would influence warfighting. Instead, as Su’s biography notes, “it was as if the abstract slogan of people’s war could solve all problems.”

20

In a series of reports to party and military leaders, Su assessed China’s military strategy and critiqued the focus on luring the enemy in deep.

Su spent almost a year drafting his initial report on how China should fight a future war. Drafting was difficult, as he held many views that were “obviously different from dominant views within the party and army.”

21

Entitled “Operational Guidance in Future Anti-Aggression Wars,” Su submitted the report to Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Ye Jianying in February 1973.

22

A second report, “Several Issues in Future Anti-Aggression Wars,” was given to top party leaders and the CMC in late December 1974 and subsequently distributed to all Politburo members in Beijing in January 1975.

23

Because these reports were authored by a senior officer with Su’s prestige and authority on strategy, and distributed at the highest levels in the party and the PLA, they offer insight into changing views of the conduct of warfare.

The 1973 report contained the basic ideas that Su would develop throughout the rest of the decade. The clear implication is that the PLA’s existing strategy was ill suited to the threat that China faced from the Soviet Union, which was characterized by vast armored forces with unprecedented firepower and mobility along with air power. Although Su Yu blamed Lin Biao for the PLA’s current shortcomings, he was really critiquing Mao’s 1964 strategic guideline, which Lin had implemented.

24

Su argued that China’s troops were too dispersed, which would weaken their effectiveness, strength, and ability to conduct maneuver operations, placing China in a passive position.

25

More controversially, he questioned the primacy of mobile warfare by suggesting that some cities and key strategic points (

yaodian

) “must be resolutely defended tenaciously” and that even “some must be defended to the death [s

ishou

].”

26

Su stressed that “there should be sufficient understanding” of the importance of positional defensive operations, which relied on fixed fortifications to blunt assaults.

27

He also challenged luring the enemy in deep by highlighting the importance of operations on open plains and around transportation nodes, rather than just retreating to mountainous areas. Specifically, he suggested that such operations would require an in-depth deployment of forces (

zongshen peizhi

) along with the construction of anti-tank obstacles and improved use of

artillery to destroy invading armored forces. He also underscored the importance of denying the Soviets air control by strengthening China’s air defenses.

By 1975, Su Yu believed a fundamental shift in the conduct of warfare had occurred. In a lecture on anti-tank warfare, Su stated that “future wars will be unlike those” against Japan, the Nationalists, or the United States.

28

He stressed that the Soviet Union’s advanced weaponry, especially its tanks and armored vehicles, could not be destroyed using the PLA’s traditional methods of “gouging eyes” (throwing grenades through sight openings) and “cutting ears” (crawling on tanks to remove the antenna).

29

Although not always explicit, Su’s concern was not just with Soviet intentions, but rather the Soviet Union’s advanced weaponry and new operational methods.

For military professionals around the world, the 1973 Arab-Israeli War marked a turning point in modern military operations. A key question is whether this conflict influenced China’s assessments of the Soviet military threat, given the prominence of Soviet weaponry and tactics in the Egyptian and Syrian armed forces. When the 1973 Arab-Israeli War occurred, the PLA’s research institutes were only beginning to resume normal operations.

30

Documents from the period are extremely limited. Nevertheless, available sources suggest that the war informed China’s assessments of the Soviet threat.

In January 1974, the GSD dispatched a delegation to Egypt and Syria to study the conflict. The seven-person delegation was headed by Ma Suzheng, the deputy commander of the engineering corps, and spent two weeks in the region as guests of the Egyptian and Syrian militaries. When the delegation returned in February, Ma briefed the leadership of the general departments and authored a report on the war. He noted that anti-tank and antiair operations were the “main defining features of the conflict” and “the tactics of the two sides basically reflected the operational thought of the Soviet Union and United States.”

31

Importantly, he stressed, “the experience and lessons of the October War were beneficial for our army’s preparation for war against foreign aggression.”

32

Ma’s report, along with materials on the war from the Egyptian and Syrian militaries, were approved for wide distribution within the PLA, “attracting attention from leaders at all levels.”

33

Ma’s report and related materials almost certainly informed Su Yu’s analysis. Su’s reports are consistent with the characteristics of this conflict, especially the focus on the speed and lethality of armored assaults, the role of anti-tank weapons, and the importance of achieving or denying air superiority. These same features of the 1973 war were highlighted in a 1975 article in the

Liberation Army Daily

, which also suggests that the lessons of the war were widely discussed within the PLA. The article notes that the war was characterized by the use of multiple offensives to achieve frontal breakthroughs, the role of large numbers of tanks in these offensives, the effectiveness of anti-tank weapons, the struggle for air superiority and the success of Egypt’s air defenses, the use

of US and Soviet weaponry, and the rapid consumption or expenditure of equipment.

34

THE 1977 STRATEGIC GUIDELINE

Despite Su’s reports, China did not change its military strategy. In fact, during a rare plenary meeting (

quanti huiyi

) of the CMC held in December 1977, the CMC instead affirmed and formalized Mao’s strategy from the mid-1960s, calling it “active defense, luring the enemy in deep.” This plenary meeting was the first meeting of the PLA high command after the death of Mao and arrest of the Gang of Four, following the election of a new CMC at the Eleventh Party Congress in August 1977. At the meeting, Ye Jianying, CMC vice-chairman in charge of daily affairs, called for “carrying out Chairman Mao’s strategic thought and completing war preparations.” Ye repeated the basic tenets of Mao’s strategy, affirming that “the basic method is annihilating the enemy through movement [

zai yundong zhong

],” that the strategic guideline was “active defense, luring the enemy in deep,” and to “be rooted in fighting an early, major and nuclear war.”

35

Nevertheless, some senior military officers did call for a change in strategy. At the 1977 plenary meeting, Song Shilun, the president of AMS, argued that luring the enemy in deep should be dropped as part of China’s strategic guideline, stating it was “inadvisable.”

36

In January 1978, Su Yu submitted a report to Xu Xiangqian, head of the CMC’s strategy commission, that also rejected a strategy based on luring in deep and outlined a strategy of forward defense.

37

Su highlighted the importance of building fortifications, using strategic reserves to conduct counterattacks, and increasing the importance of positional warfare. His report, discussed in more detail below, was then circulated to the CMC vice-chairmen, including Deng Xiaoping, and within the GSD.

The 1977 plenary meeting most likely maintained luring the enemy in deep as a temporary measure. Senior military officers understood the need to rebuild an armed force that had been ravaged by the Cultural Revolution. Although Mao had changed China’s strategy to luring in deep in 1964, it had never been adopted formally by the PLA. Thus, as Ye Jianying noted at the plenary meeting, one imperative for the PLA after the Cultural Revolution was “to unify operational thought,” a prerequisite for consolidating and rebuilding the force as a whole.

38

By emphasizing Mao and the existing strategy, Ye invoked a leader whom all in the PLA could support and attributed the PLA’s deficiencies to Lin Biao and the Gang of Four.

39

Similarly, as Deng said at the meeting, “without a clear strategic guideline, many matters cannot be handled well.”

40

For these reasons, one general recalls that the 1977 strategic guideline “played an important role in promoting army-building and war preparations after the smashing of the Gang of Four.”

41

Raising the question of changing military strategy so soon after Mao’s death would have invited broader reexamination of his

legacy that the party and the PLA were not yet ready to undertake, especially given the divisions among the top party leaders over the structure of authority. Mao also still enjoyed a great deal of admiration among the PLA’s grassroots, who joined the force during the Cultural Revolution.

CONSENSUS BUILDS FOR CHANGE AMONG THE HIGH COMMAND

In early 1978, Su Yu continued his challenge of luring the enemy in deep. His 1978 report to Xu Xiangqian, discussed above, was entitled “Several Opinions on Strategy and Tactics in the Initial Phase of a War.”

42

Su observed that “whether the initial phase of the war is fought well will have a significant relationship on the development of the entire course of the war.”

43

He then stressed the importance of identifying key defensive points (

fangshou yaodian

) and increasing the size of the reserve forces in the center of the country. Again challenging the existing strategy, he believed that “the initial phase of future wars will be different when compared with many past wars.”

44

For example, “the proportion of defensive positions [

zhendi shoubei

] should be increased and our army’s positional warfare capability must be raised” to resist waves of armored and artillery attacks.

45

Foreshadowing a focus on combined arms, Su called for infantry, armored, engineering, and air forces as well as the militias to create a “tight anti-tank firepower network [

huowang

]” with long, medium and short ranges.

46

In April 1978, Su Yu repeated similar themes in a lecture at AMS.

47

Given the speed and range of the Soviet Union’s heavy weapons, Su concluded that “our operational methods, ways, and means must also change and even must be transformed.”

48

The PLA needed to employ more troops in defensive operations, limit mobile operations at the start of the war to supporting defensive operations, and avoid decisive battles in which the poorly equipped PLA forces would suffer heavy losses. In the civil war, Su said, “we generally used mobile defense,” but this required gradual retreats that would now require abandoning cities that he believed should be defended to the death, given their importance for China’s ability to mobilize its population for a longer war. Su grounded his arguments in shifts in the conduct of warfare, and repeatedly referred to “the rapid development of modern science and technology and its extensive use in the military.” For Su, this “inevitably will lead to changes and even a transformation in operational methods, raising a new series of problems for war preparations [

zhanzheng zhunbei

].”

49

Su Yu’s challenge to China’s existing strategy gained much wider exposure in January 1979, when he was invited to lecture at the PLA’s Military Academy and the CCP’s Central Party School. He examined “solving operational problems under modern conditions,” or how to deal with the Soviet threat based on

the shifts in the conduct of warfare.

50

Importantly, he delivered his talk shortly before China’s invasion of Vietnam the following month. Although China’s poor performance in this conflict may have created an additional impetus for military reforms, Su’s views on shifts in the conduct of warfare as a reason to change strategy were formed well before China’s invasion and whatever lessons might have been learned on the battlefield.

51

He began with the observation that advances in science and technology heralded a new stage in the development of weapons, equipment, and war-fighting methods. According to Su, “these changes challenge some of our army’s traditional operational arts and urgently demand that our army develop our strategy and tactics.” Otherwise, “as soon as the enemy launches a large-scale war of aggression, we may not be able to adapt to the requirements of the circumstances of the war and may even pay much too high a price.”

52

The Soviet and US militaries were dominated by heavy weapons that were “armored, fast, powerful, and long range.” For this reason, Su argued, “the destructive power and lethality of modern conventional weapons are unmatched in the past,” and would play a key role in warfare especially in a war with its northern neighbor.

53

As he quipped, “Even if you make a lot of noise using bullets and grenades against tanks, you cannot destroy the tanks.”

54

For China, the main challenge in a war with the Soviet Union would be countering a surprise attack. Soviet military theory viewed the opening phase of the war as decisive, determining whether a rapid victory could be achieved.

55

Soviet advantages in weaponry would allow them to rapidly strike China’s strategic political, economic, and military centers, and thus paralyze China’s “defensive system” and destroy its ability to resist. The key issue was “resisting the first few waves of the enemy’s strategic surprise attack” while maintaining the PLA’s effective strength and avoiding concentrating forces and decisive battles.

56

Su’s answer, consistent with his previous writings, contradicted the existing strategy by emphasizing positional warfare over mobile warfare. As Su said, “An important difference with the past is that positional defensive warfare has clearly grown in importance.”

57

Mobile warfare should be restricted to areas near fixed positions and medium-sized battles in prepared positions behind the front line. “Under modern warfare conditions,” he said, “at the beginning of the war, the main feature of the form of operations will be positional operations [

zhendi de zuozhan

] and operations not far from these positions.”

58

Although mobile warfare had been the mainstay of PLA offensive campaigns in the Korean War, he stated that it emphasized mobility without taking rear areas into consideration that would now be critical in mobilizing the nation. As Su noted, “In the past, we would attack if we could win, and flee if we could not, but now whether or not we can win or lose, there is a still a problem whether or not we can get away.” Thus, “if we copy that way of fighting from the revolution, it would not be pragmatic.”

59

Instead, “the situation of future wars of

anti-aggression was different” because China would need to defend key fortifications (

zhongdian shefang

) and garrison areas, including key cities, islands and coastal areas as well as other strategic areas.

60

Although some areas could be abandoned, others the PLA must “defend to the death.” For Su, some cities not only needed to be held, but also could be used like Stalingrad as an opportunity to weaken the enemy.

Su Yu’s speech received a great deal of publicity. A Xinhua reporter attended the meeting and introduced its basic ideas to a wider audience.

61

The GSD organized staff to listen to recordings of the lecture. By March, seventy percent of cadres in the GSD had heard the speech.

62

The lecture was published in an internal AMS journal,

Military Arts

, in March 1979 and then in the widely circulated

Liberation Army Daily

newspaper on May 15, 1979, sparking vigorous debate and discussion.

63

The CMC also instructed that Su’s speech be distributed as required reading for all senior cadre in the army, which indicated high-level approval of the contents of his lecture.

64

That summer and fall, many senior officers publicly endorsed Su’s ideas and called for a new strategy. In October 1979, for example, Xu Xiangqian, one of the PLA’s ten marshals, published a lengthy article on defense modernization in

Red Flag

, a publication under the Central Committee, that linked changes in the conduct of warfare with questions of strategy. Xu noted how the application of new technologies to military affairs was “causing great changes in weaponry and equipment.” Furthermore, “these changes will inevitably lead to corresponding changes in operational methods.” For Xu, “modern warfare is very different from any war in the past.” In a war with the Soviet Union, for example, “the target of attack, scale of war, and even method of fighting are something we have not encountered before. We must study and solve a number of new problems according to these new conditions.” Rejecting Maoist ideas, Xu said that “if we view and command a modern war with the old vision of the 1930s and the 1940s, we are bound to be rebuffed and suffer great hardships in a future war.”

65

The clear implication of Xu’s remarks was that China needed a new strategy.

Over the following year,

Military Arts

published articles supporting Su’s position, including many by senior officers.

66

In November 1979, for example, Yang Dezhi endorsed Su Yu’s ideas about the importance of defensive operations and positional warfare. Yang would replace Deng Xiaoping as chief of the general staff in March 1980. Yang observed that the CMC had already determined China’s strategic guideline, but acknowledged that issues remained regarding “how to better understand and implement the guideline”—a not so subtle way of saying that the guideline should be revised. More bluntly, he said the core issue was whether to “resist the enemy’s strategic breakthrough” or “carry out luring the enemy in deep.”

67

He then argued for emphasizing positional warfare and for improving coordination among the services and combat arms as the key to success.

6

8

Many commentaries on Su’s speech in

Military Arts

used the 1973 Arab-Israeli War as an important example. In a January 1980 speech at AMS, for example, Song Shilun repeatedly referred to the 1973 war when describing the characteristics of modern warfare, such as the high consumption of weaponry and the importance of strategic surprise.

69

Similarly, when commenting on how to revise a draft of the

Science of Campaigns

in August 1980, Song instructed that researchers at AMS should “appropriately borrow from the campaign operational experience of foreign armies, especially the operational experience of the Fourth Middle East War.”

70

The

Science of Campaigns

was to serve as a guide for how to conduct campaigns and thus should “strive to reflect operational characteristics under modern conditions.”

71

The 1973 Arab-Israeli War had also become an important reference point for training. A report from the Shenyang Military Region in late 1978, for example, notes that the war was used as the main case study (

zhanli

) for anti-tank operations.

72

In 1979, the war featured prominently in anti-tank training in the Beijing Military Region.

73

In 1981, a study group at an army in the Nanjing Military Region was established to study surprise attacks in the opening phase of a war. The group used three books, including one entitled

The Fourth Middle East War

.

74

Most likely, similar study groups were formed in other military regions. Likewise, in 1985, AMS published a translation of a Japanese study of the Arab-Israeli wars. The preface written by AMS stated that “in the history of warfare to this day, the Fourth Middle East War is the one war that prominently reflects modern characteristics.”

75

The Deng-Hua Power Struggle and Restoration of Party Unity

Although senior PLA officers recognized by 1978 that China needed to change its military strategy, a new strategic guideline was not adopted until October 1980. The main obstacle was the disunity in the highest levels of the party, created by the politics of the Cultural Revolution, that continued even after the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. The restoration of party unity required that a new consensus be reached on the structure of power and authority within the party, which was achieved when Deng Xiaoping defeated Hua Guofeng in a struggle to become China’s top leader.

FRAGMENTATION AT THE TOP

When Mao Zedong died in September 1976, four contending elite groups or factions existed. The “leftists” were radicals unleashed by Mao to rectify revisionism he believed had taken root in the party, who controlled propaganda and education, among other areas. The most prominent members of this group

were the so-called “Gang of Four,” although they had not always operated as a unitary group in the Cultural Revolution.

76

The “beneficiaries” were those party elites whose careers had prospered during the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution and found themselves in elevated positions of power after more senior leaders were persecuted. The veteran “survivors” included those older members of the party who largely avoided being purged, either because they had been protected by Mao or Zhou or because they successfully navigated the ever-changing politics of the time. Waiting in the wings, however, was a fourth group: the “victims” or members of the old guard who held senior positions before 1966 and had then been persecuted. These individuals were often associated with more pragmatic and less radical policies before the Cultural Revolution and had held important positions in the party, state, and military. They most likely resented the beneficiaries, who often occupied posts that they had vacated, but also possessed the bureaucratic skills and extensive connections within the party that would be needed to rebuild the country when the Cultural Revolution ended.

77

To varying degrees, the Cultural Revolution created divisions within the party, state, and military. When Zhou Enlai died, the position of premier of the State Council became vacant for the first time since 1949. Mao appointed Hua Guofeng, a beneficiary, to replace Zhou because a leftist would have lacked support from other senior leaders. As first vice-premier throughout 1975, Deng Xiaoping would have been Zhou’s logical successor. Deng, however, had fallen out of favor with Mao at the end of 1975 and would be stripped again of his positions in April 1976. When Hua became premier, he was also named as the first vice-chairman of the CCP, indicating that he had become Mao’s chosen successor.

78

When Mao died in September 1976, the positions of party chairman and CMC chairman became vacant. An alliance formed between veteran survivors, led by Ye Jianying, and the beneficiaries, such as Hua Guofeng. Following a series of moves by the Gang of Four to consolidate power immediately after Mao’s death, the leading survivors and beneficiaries agreed to the arrest of the “gang” and their key supporters, thus rejecting a radical vision for the future of the party and eliminating one group contending for power.

79

The Politburo named Hua as the chairman of both the CCP and the CMC. Hua thus became the first political leader since 1949 to hold the top positions in the party, state, and military.

Hua’s formal titles, however, exceeded his informal authority and status within the party. After the arrest of the Gang of Four, the Politburo Standing Committee had only two members: Hua (chair) and Ye Jianying (vice-chairman). A new Politburo Standing Committee would need to be formed, which required convening a party congress. When the Eleventh Party Congress was finally held in August 1977, almost a year later, new leadership bodies were formed but they

reflected an unstable balance among beneficiaries, survivors, and victims. Hua remained chairman of the CCP and thus chairman of the Politburo Standing Committee. Wang Dongxing, another beneficiary who played an instrumental role in the arrest of the gang, was named as vice-chairman of the party in addition to running the powerful central office of the CCP. Two survivors joined the new Politburo Standing Committee: Ye Jianying, who had been in charge of the PLA’s daily affairs, and Li Xiannian, one of Zhou Enlai’s economic advisors. The final member, Deng Xiaoping, represented the aspirations of the many victims.

Deng’s return to work in 1977 required delicate negotiations between the beneficiaries and veteran survivors. Wang Dongxing and Wu De, the mayor of Beijing and another beneficiary, opposed Deng’s return. But many others supported it, especially given the need to address widely acknowledged problems in the military. Deng wrote in a disingenuous letter in May 1977 that he accepted Hua’s leadership of the party.

80

In July 1977, Deng assumed all the positions he had held in 1975—vice-chairman of the party, vice-chairman of the CMC, vice-premier, and chief of the general staff. By resuming positions in all three pillars of power, Deng also posed a clear threat to Hua Guofeng. The disunity within the highest levels of the party was reflected in the official ranking of Politburo members: Hua a beneficiary ranked first, Ye a survivor second, and Deng a victim third.

81

Although the top party leadership remained divided, the new CMC formed after the Eleventh Party Congress was more favorable to Deng than any other leader. Hua remained chairman, with Ye Jianying, Deng Xiaoping, Liu Bocheng, Xu Xiangqian, and Nie Rongzhen as vice-chairmen. All but Hua were military professionals who had been involved in the PLA’s modernization since the 1950s. The nucleus of the new CMC was its standing committee (

changwei

), which had eight members and would serve as the CMC’s principal decision-making body. Only one member of this committee, Wang Dongxing, had strong ties to Hua.

82

The new CMC also had forty-three additional members, including the leadership of the three general departments, services and branches, military regions, and other units under the CMC. Thus, the CMC, like the PLA itself, was both bloated and fragmented, unable to take quick or resolute decisions.

DENG’S CONSOLIDATION OF POWER

Starting August 1977, Deng waged a steady campaign to consolidate power within the CCP. Following the arrest of the Gang of Four, the struggle for power occurred mainly between the beneficiaries around Hua Guofeng and the return of victims around Deng. In addition, within the lower ranks of the party and military, many beneficiaries and leftists remained, both of which could be mobilized by top party leaders and underscored the fragility at the

top of the party. In this contest, Hua had two advantages. He held the top positions in the three institutional pillars of power, while also having been blessed by Mao with legitimacy as the chairman’s chosen successor.

83

Hua’s status as Mao’s successor, however, also linked him to any reevaluation of the Cultural Revolution, which would touch on Mao’s responsibility for what had occurred.

84

Deng ranked lower in the party, state, and military hierarchies, but nevertheless held senior positions in each, along with years of experience at the highest levels of policymaking from the founding of the PRC, which Hua lacked. Deng was especially powerful within the PLA, not just because of his historical ties with many of the top leaders on the CMC, but also by serving as a vice-chairman of the CMC and as chief of the general staff. Deng represented the aspirations of many others, inside and outside the military, who had been persecuted by the leftists and resented the beneficiaries.

As new research on Chinese elite politics demonstrates, the contest between Deng and Hua did not reflect underlying differences over policy or ideology. Deng and Hua surprisingly agreed on many policy issues, especially economic ones.

85

Where they likely disagreed would concern the future of the party, the evaluation of the Cultural Revolution, and, most important, the structure of power at the top of the party.

86

The struggle between Hua and Deng will not be recounted in detail here.

87

For the purposes of explaining major change in China’s military strategy, the most important element of the struggle was the outcome—namely, the consolidation of authority and restoration of unity within the party under one leader, Deng Xiaoping.

Deng consolidated power over the next year and a half, roughly in two phases. In the first phase, which culminated in the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Party Congress in December 1978, Hua Guofeng and other beneficiaries were significantly weakened. As Joseph Torigian shows in exciting new research, Deng exploited Hua’s political vulnerability as Mao’s successor by promoting a debate over “practice is the sole criterion for judging truth,” which questioned the utility of Maoist ideas under the slogan of the “two whatevers.”

a

As Torigian concludes, “Deng had artificially manufactured an ideological debate he could turn into a political debate.”

88

By the fall of 1978, most provinces and key military units had all expressed support for Deng’s position on “seeking truth.”

89

The turning point in Hua’s weakening occurred at a central work conference that was held in November 1978. The purpose of the conference was to discuss economic policy that would be ratified at the Third Plenum the following month. Nevertheless, almost as soon as the conference started, participants quickly changed the agenda to discuss reversing the verdicts of victims of the

Cultural Revolution as well as those who had been implicated in the April 5, 1976, “Tiananmen Incident” that Hua had so far refused to reverse.

90

Although not the first to speak out, the most senior member of the party to raise these issues early in the meeting was Chen Yun, who called for the rehabilitation of veteran party members who had been criticized (including himself).

Chen Yun insisted that the reversal of verdicts must be addressed before tackling policy issues such as the economy. In the end, Hua Guofeng acceded to the demands Chen and others raised on reversing verdicts and adding victimized revolutionaries to the Politburo.

91

Many of Hua’s supporters, such as Wang Dongxing, Wu De, Chen Xilian, and Ji Dengkui, performed self-criticisms for maintaining “leftist” positions associated with the Cultural Revolution. When the Third Plenum was held in mid-December, it confirmed the reversal of verdicts, placing more supporters of Deng on the Politburo. Wang Dongxing was removed from his positions as party vice-chairman and as director of the Central Committee’s general office. Chen Yun replaced Wang as party vice-chairman and also joined the Politburo Standing Committee.

By this time, Deng had begun to exercise the authority of a paramount leader. Deng altered work assignments for those on the Politburo and Politburo Standing Committee, actions normally reserved for the party chairman, such as Hua.

92

Even before the work conference had started, Deng oversaw the negotiations for the normalization of diplomatic relations with the United States and pushed for a punitive attack on Vietnam in February 1979 for Hanoi’s alignment with Moscow and invasion of Cambodia.

93

Previously, only Mao (or Zhou with Mao’s approval) would have handled high-level diplomatic negotiations or decisions regarding the use of force. Hua Guofeng played little or no role in these decisions.

After the Third Plenum, Deng continued to consolidate power in the party, state, and military. In November 1979, the Central Committee approved the CMC’s establishment of an “office meeting” (

bangong huiyi

) that would be responsible for managing daily affairs.

94

This executive body was packed with Deng supporters.

95

In January 1980, more Deng loyalists were added to the CMC Standing Committee.

96

Between January and April 1980, the leadership of several military regions was reshuffled. Commanders in all but two of the eleven military regions were replaced. In many cases, the reshuffling occurred because existing commanders were tapped for promotion into higher positions.

97

Like other major leadership changes within the PLA’s military regions, however, the rotation of commanders may have also been intended to prevent the “mountaintops” or factions that arise when one commander serves in the same region for a long period of time. The reshuffling allowed for the promotion of younger commanders—a long-standing goal of Deng’s. Many of those promoted had also been persecuted during the Cultural Revolution and none of them had strong ties with Hua Guofeng. Finally, the ability to execute the reshuffling was also

a sign of Deng’s consolidation of power within the PLA.

98

No evidence exists that Hua was involved in these changes.

Deng’s consolidation of power within the military presaged his move against Hua Guofeng in the party and state bureaucracies. At the Fifth Plenum, in February 1980, four members of the Politburo Standing Committee close to Hua Guofeng were removed, while Zhao Ziyang and Hu Yaobang were added.

b

The balance on the standing committee now favored Deng. Hu Yaobang was named as general secretary of the CCP, which placed him in charge of party affairs. Zhao Ziyang assumed responsibility for the daily work of the State Council and would officially replace Hua Guofeng as premier in August.

99

Although Hua would remain party chairman and CMC chairman for a few more months, he had been effectively sidelined from the party and state bureaucracies. In December, at a series of Politburo meetings, Hua relinquished these last two positions, a decision that would be formalized at the Sixth Plenum in June 1981.

100

Adoption of the 1980 Strategic Guideline

This restoration of party unity created conditions for changing China’s military strategy. By the end of 1979, a consensus had emerged on the need to resist a Soviet invasion through a forward defense and not a strategic retreat. Now, the PLA’s leadership could act on that consensus. The decision to formulate a new strategic guideline was made in the spring and summer of 1980 and the new strategy was adopted in October 1980. The decision to adopt the new strategy demonstrates how senior military officers led the process of strategic change.

THE DECISION TO CHANGE STRATEGY

The move to change strategy began when Deng Xiaoping decided to step down as chief of the general staff in early 1980 to focus on economic and party affairs. Yang Dezhi, the commander of the Kunming Military Region who had led Chinese forces on the Kunming front in China’s 1979 invasion of Vietnam, replaced Deng. By this point, most members of the CMC along with the leadership of the three general departments could be described as “modernizers” focused on military affairs and not politics. Within the GSD, Yang Dezhi’s deputies were Yang Yong, Zhang Zhen, Wu Xiuquan, He Zhengwen, Liu Huaqing, and Chi Haotian.

Yang’s first task as chief of the general staff was to develop a plan to streamline and reorganize (

jingjian zhengbian

) the force. This had been raised at the

1975 enlarged meeting of the CMC, but only limited progress was achieved following Deng’s removal from office in 1976 and continued divisions within the party and PLA. Although 800,000 troops had been cut by the end of 1976, mostly from the ground forces, the size of the PLA grew again in the late 1970s, reaching 6,024,000 in 1979.

101

Streamlining and reorganization became the focus of an enlarged meeting of the CMC held in March 1980, as discussed in more detail below.

Yang’s second task was to formalize the consensus around China’s military strategy, specifically the PLA’s “operational guiding thought” during the initial phase of a war with the Soviet Union. The first downsizing would need to be informed by an overarching vision for how the PLA should be organized and the operations that it would be required to execute. More important, a gap formed between the emerging consensus following the open publication of Su Yu’s 1979 lecture and the existing strategic guideline of “active defense, luring the enemy in deep.” Su’s emphasis on positional warfare contradicted the concept of strategic retreat in the existing strategy. If the PLA was going to emphasize positional warfare, the CMC would need to revise the strategic guideline. The speed with which Su’s ideas were embraced by the high command after his 1979 speech and the gap with the existing guideline indicated the need to “unify thought” (

tongyi sixiang

) on strategy and operations.

Several military regions had already started to implement Su Yu’s ideas even though the strategic guideline had not yet been changed. In October 1979, for example, the Shenyang Military Region conducted a division-level exercise of positional defensive operations under nuclear conditions that was consistent with a greater emphasis on defending fixed positions following an initial attack.

102

In March 1980, the Shenyang Military Region held a training session that used Su’s speech as the basis for evaluating the region’s objectives and training plans.

103

In March 1980, the GSD and Wuhan Military Region instructed the 127th Division to conduct pilot training to improve coordination (

xietong

) to strengthen positional defense against an attacking enemy—the very kind of operations that Su had urged the PLA to emphasize.

104

Shortly after replacing Deng, Yang Dezhi chaired several meetings to discuss the international situation and the PLA’s operational guiding thought in a war with the Soviet Union. Based on these discussions, Yang proposed to the CMC on May 3 that the GSD convene a seminar (

yanjiuban

) for senior officers on operations in the initial period of an “anti-aggression” war.

105

As he would later note, such a seminar for top officers was unprecedented.

106

The purpose of the meeting was to raise the “strategic awareness” (

zhanlue yishi

) of senior officers and discuss how to respond strategically to a Soviet attack.

107

The broader goal was to change the strategic guideline, as the PLA could not answer the question of how it should respond to a Soviet attack without describing what

kind of military strategy China should have. To maintain secrecy, the seminar was codenamed the “801” meeting.

108

The CMC agreed with Yang Dezhi’s proposal and placed him in charge of a leading small group to organize the seminar. Zhang Zhen served as head of the group’s office and was put in charge of day-to-day planning. Yang and his deputies agreed that the first issue to decide was the “correct expression” (

zhengque biaoshu

) of the strategic guideline “to unify the thinking of the whole army.”

109

The purpose of the seminar would be to discuss how to change China’s military strategy in the context of a war with the Soviet Union. In describing the work of the leading small group, for example, Zhang Zhen refers on multiple occasions to revising the guideline.

110

In the beginning of June, Yang Dezhi and Yang Yong, the first deputy chief of the general staff, spent one month conducting an inspection tour of Inner Mongolia, the Hexi Corridor and Helan Mountains, all different areas that would be on the frontline in any war with the Soviets. The trip’s purpose was to inspect the combat readiness training, defensive fortifications, and terrain where an invasion might occur. Underscoring the importance of the trip, they were accompanied by leaders of the Beijing and Lanzhou Military Regions.

111

As Yang Dezhi would say several months later, “We discovered many problems.”

112

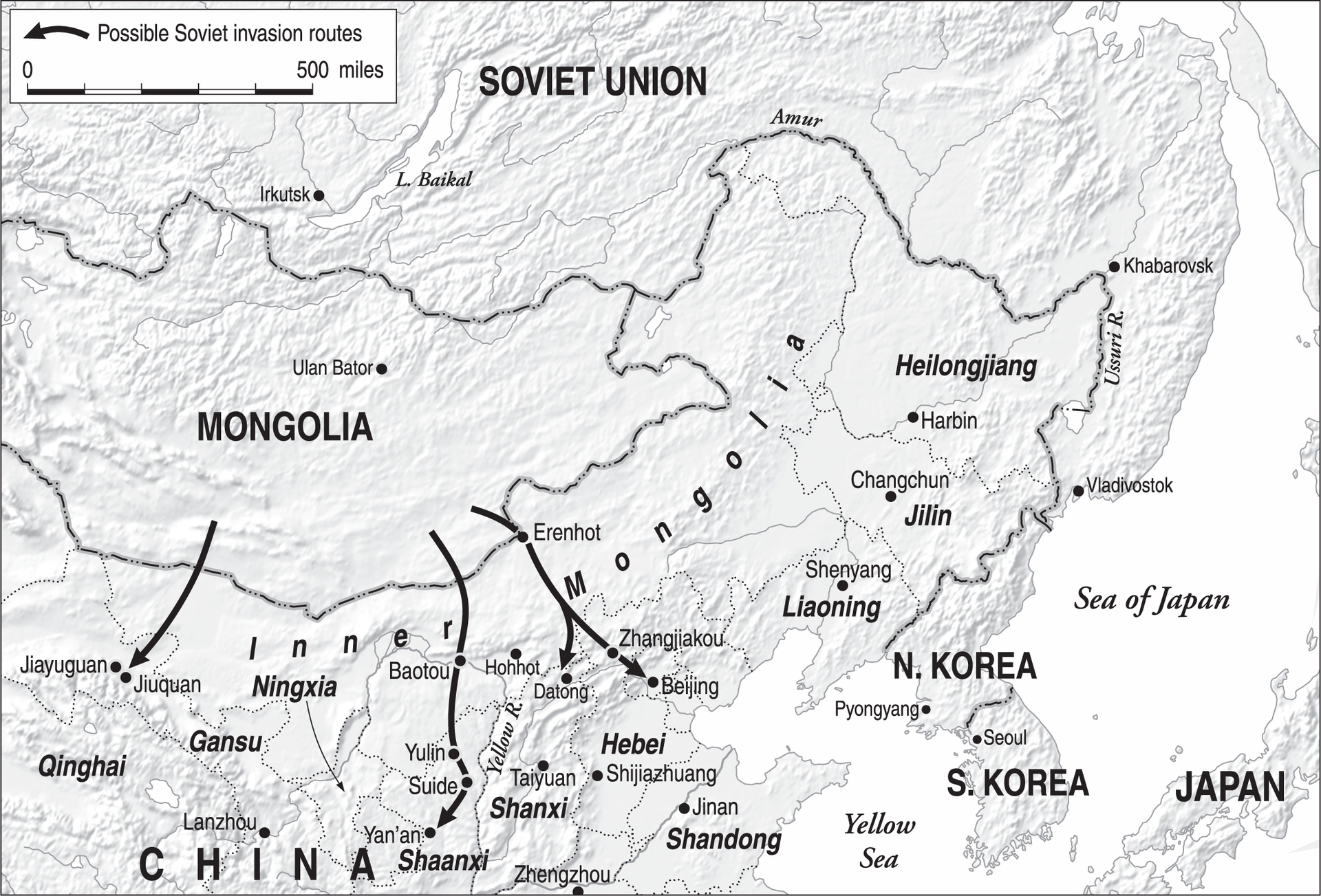

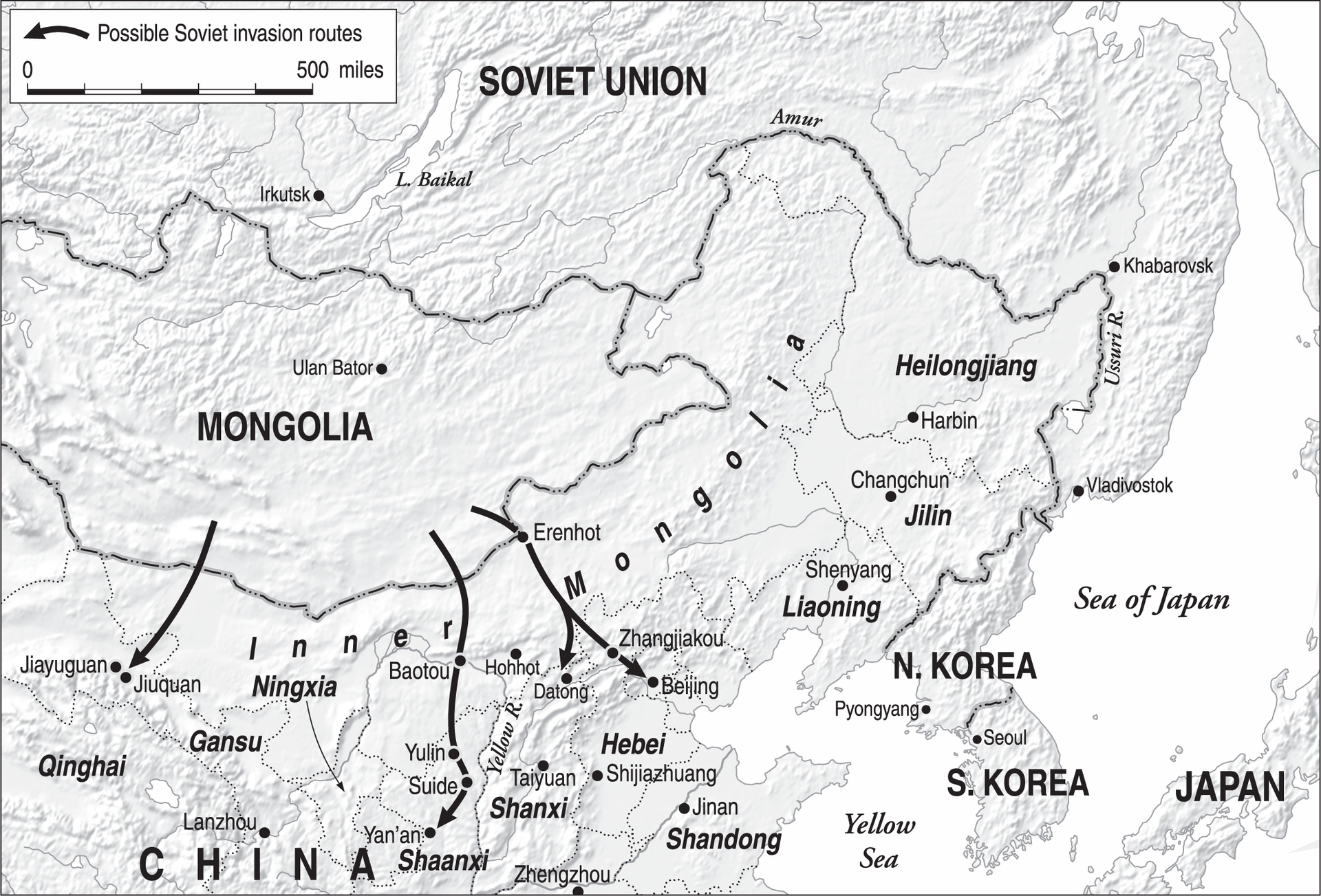

As shown in

map 5.1

, three potential Soviet invasion routes had been identified in the early 1970s.

113

The route from Erenhot to Beijing through Zhangjiakou was the shortest and most threatening.

In the middle of June, Zhang Zhen began to prepare a series of lectures that would form a core part of the seminar. These lectures involved leaders from fifteen units and departments to study how to employ the services and branches in the initial phase of a war. Topics included how a breakthrough in a campaign could evolve into a strategic breakthrough, the coordination among the services and branches, command automation, electronic countermeasures, air defenses, and wartime mobilization, among others. Lectures also covered the operational characteristics of World War II and “several wars that recently occurred in the world,” presumably including the 1973 Arab-Israeli war.

114

To avoid “empty talk,” all speakers held practice lectures (

shijiang

) that the small group supervised.

115

By the middle of August, preparations for the seminar were complete. At some point during this process, the leading small group decided that the strategic guideline should be changed and that “luring the enemy in deep” should be removed as part of the formula or expression of the guideline. Zhang Zhen, for example, recalls discussions with Yang Dezhi and Yang Yong in which they agreed on how to change the guideline, though he does not state exactly when these conversations occurred.

116

The leading small group solicited the opinions on changing the strategic guideline from the CMC’s strategy commission and

“relevant leading cadre.”

117

According to Zhang Zhen, “Everyone favored [

qingxiangyu

] making a partial adjustment to the strategic guideline.”

11

8

MAP 5.1.

The northern strategic direction in the 1980 strategy

Between mid-August and the start of the seminar on September 17, the leading small group consulted with the old marshals and vice-chairmen of the CMC to seek their approval for the change in strategy. Nie Rongzhen, Ye Jianying, and Xu Xiangqian all agreed with the proposed revision of the guideline, pending CMC approval.

119

On September 30, the leading small group briefed Deng Xiaoping, who “clearly affirmed our views” and stated that he wanted to address the seminar.

120

The CMC approved the change in the guideline during the seminar.

121

On September 9, Song Shilun, the president of AMS, sent a letter to Ye Jianying, one of the CMC’s vice-chairmen. Song argued forcefully for dropping luring in deep from the strategic guideline because “it cannot be a strategic guideline to unify the overall war situation.” Instead, it “can only be a kind of operational method under certain conditions, in certain strategic or campaign directions in a certain period of time.”

122

The relationship between Song’s letter and the deliberations of the leading small group is unclear.

123

Nevertheless, the old marshals endorsed Song’s letter, and they agreed that luring the enemy in deep should be dropped from China’s strategic guideline, as the leading small group had proposed.

124

THE “801” MEETING

The army-wide senior officer’s seminar on defensive operations, or the “801” meeting, began on September 17 and lasted for one month. More than one hundred senior officers gathered at the Jingxi Hotel in Beijing, including from the CMC, general departments, military regions, services, branches, and other departments.

125

The rostrum included the CMC secretary Geng Biao, Yang Dezhi, the GSD’s leadership, and the CMC’s advisors (

guwen

). The purpose of the meeting was to focus on global strategic trends, the assessment of a foreign invasion, the strategic guideline, operational guiding thought, and the PLA’s strategic tasks (

zhanlue renwu

) in the initial phase of the war.

126

In his opening remarks, Yang acknowledged how party disunity had hampered the development of military strategy. “Regarding operational thought,” he said, “the interference and destruction of Lin Biao and the Gang of Four cannot be underestimated. Therefore, for a long period of time, conditions have not existed to unify operational thought.”

127

Yang outlined the goals of the meetings as “studying and researching operational issues in the initial phase of an anti-aggression war, deepening understanding of the CMC’s strategic guideline, unifying operational thought, and further implementing all combat readiness work [

zhanbei gongzuo

].”

128

Later in the seminar, Yang Dezhi gave another speech in which he outlined the central role that positional warfare

should play in China’s new strategy and operations for dealing with a Soviet invasion.

129

At the time, open criticism of Mao, especially on military affairs, remained sensitive. When the seminar was held, the party had not yet reached its official judgment of Mao, which would be contained in the June 1981 resolution on party history. Toward this end, AMS under Song Shilun’s direction attempted to gather all statements made by Mao on luring the enemy in deep. Song concluded that even when Mao had used the term, most of the time it was in the context of campaigns and tactics, not at the strategic level. The only time it was used at the strategic level, apart from in the mid-1960s, was during the Red Army period in the 1930s.

130

Therefore, Song and others argued that dropping luring the enemy in deep as a strategic concept was not inconsistent with much of what Mao had said, thereby creating ideological space for rejecting the existing strategy based on one of Mao’s foundational ideas. Moreover, Song cleverly argued that the concept of active defense included the idea of luring the enemy in deep at the operational level.

131

These ideological gymnastics supported the abandonment of strategic retreat in favor of positional warfare.

At the conclusion of the seminar, Deng Xiaoping and Ye Jianying addressed the participants to endorse the change in strategy. In his straightforward style, Deng said, “For our future anti-aggression war, what guideline should we adopt after all? I approve these four characters—‘active defense.’ ”

132

Ye Jianying concurred, “During this discussion everyone advocates for ‘active defense’ … I agree with everyone’s opinion.”

133

Yang Dezhi summarized what the meeting had accomplished. For him, it “basically unified understanding of the CMC’s strategic guideline, further clarified strategic guiding thought and strategic tasks in initial phase of a future war, [improved] understanding of the situation of the services and branches, and strengthened the concept of combined operations [

hecheng zuozhan

].”

134

In other words, it changed China’s military strategy.

Shifts in the conduct of warfare featured prominently in discussions at the seminar. According to one account, the participants concluded that “today’s war is completely different from yesterday’s war.”

135

Moreover, “the adversary in future war was changing, weapons and equipment and ways of war [

zhanzheng fangshi

] were changing, making people dumbfounded.”

136

In his remarks at the end of the seminar, Ye Jianying underscored the role of shifts in the conduct of warfare. He told the participants that “our military thought must develop with changes in warfare.” Specifically, “fighting conventional wars will be different than in the past.” For Ye, “when a battle starts in the future, the enemy may come together from the sky, land and sea; the difference between front and rear is small. This will be an unprecedented three-dimensional war [

liti zhan

], combined war [

hetong zhan

], and total war [

zongti zhan

].” He then drew on the example of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War to illustrate how the conduct of warfare had changed and the challenge that now China faced:

When Egypt fought Israel in the Middle East war, in addition to air combat, it was mainly fighting tanks and tanks countering tanks. Ground operations had to deal with the enemy’s airborne and helicopter landings. This is not the same as how we used to fight. As for us, many aspects are also different from the past, with more special forces and heavy weapons and equipment, which is not the same as the past millet plus rifles. As the force becomes more modern, it also relies more on logistics and the organization of logistics expands. These changes between the enemy and ourselves inevitably create new problems and characteristics in future wars.

137

From an operational perspective, these shifts in the conduct of warfare indicated that the Soviet Union would be able to conduct deep and rapid strikes. If China did not try to stop, delay, or slow these strikes, the results would be devastating. Beijing, for example, was only about 380 miles from China’s border with Mongolia. Moreover, strategic retreat would likely require relinquishing these urban areas without a fight. Top officers agreed that, under these conditions, failure to resist a Soviet attack would have dire consequences. The Soviets would either be able to achieve a rapid victory if not resisted or, in a larger war, it would be able to seize cities and other industrial areas that would not only weaken national morale but also degrade China’s war potential and ability to mobilize to counterattack. Song Shilun went even further, noting that luring the enemy in deep was inconsistent with development in the types of wars since World War II. For Song, these included limited wars to seize some territory, proxy wars, and wars of quick decision (

suda sujue

). As Song wrote, “Luring the enemy in deep is not appropriate for all types of wars,” as a strategic retreat in a limited war effectively allowed the enemy to achieve its war aims without fighting or paying a price.

138

The 1980 strategic guideline is also associated with a shift in China’s naval strategy from “near-coast defense” (or coastal defense) to “near-seas defense” (

jinhai fangyu

, or offshore defense). Under the former, the PLAN focused on deterring or preventing an amphibious assault and securing the Chinese coast. With the latter, however, the purpose was broader—to also defend the waters adjacent to China. Deng Xiaoping raised the prospect of such a change in April 1979, when, in a meeting with PLAN Commander Ye Fei, Deng stressed “near-seas operations.”

139

In July 1979, Deng told the PLAN’s party committee that “our strategy is near-seas operations [

jinhai zuozhan

].” Deng’s main concern was countering the “powerful navy” of a hegemon, presumably the Soviet Union.

140

In this way, the extension of the PLAN’s area of operations was consistent with pursuing a forward defense along the land border. When discussing the PLAN’s streamlining and reorganization as part of the 1982 downsizing (discussed below), the CMC stated that the requirements of “near-seas

defense” should guide the PLAN’s reorganization, which perhaps marks the first time that the term describing the new strategy was used.

141

In August 1982, Liu Huaqing, then a deputy chief of the general staff, replaced Ye Fei as PLAN commander. Beginning in 1983, Liu started to flesh out the content of near-seas defense as the PLAN’s service strategy. The near seas are the seas adjacent to China’s coast, including the Yellow, East China, and South China Seas and the waters east of Taiwan. In January 1986, the PLAN’s party committee adopted a naval strategy under the slogan of “active defense, near-seas defense,” demonstrating a clear link to the 1980 strategy.

142

The next month, Liu Huaqing and the PLAN commissar submitted a report to the CMC requesting permission to adopt a naval strategy of near-seas defense.

143

In Liu’s vision, near-seas defense emphasized realizing Taiwan’s unification, defending territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests, and deterring attacks from the sea. Key tasks in wartime would be coordinating with the army and air force to defend China against attacks from the sea and to protect sea-lines of communication. These tasks required being able to seize and retain command of the sea for a period of time, to control sea routes connected with the near seas, and even to be able to fight in adjacent waters.

144

As Bernard Cole has observed, much of what Liu outlined was aspirational at the time, but Liu’s legacy played an important role in the 1990s and 2000s with the shift in China’s overall military strategy from total wars to local wars.

145

A RESPONSE TO POOR PERFORMANCE IN 1979?

Was the 1980 strategy adopted in response to the PLA’s poor performance in its February 1979 invasion of Vietnam? China invaded Vietnam to punish Hanoi for its November 1978 defense treaty with the Soviet Union and then Vietnam’s December 1978 invasion of Cambodia. China also sought to signal its resolve to resist the Soviet Union, who had deployed fifty divisions along China’s northern border. China’s military objective was to seize several provincial capitals and communications nodes, especially Lang Son, in order to demonstrate China’s ability to occupy Hanoi. Afterward, China would withdraw.

146

The invasion began on February 17, 1979. China mobilized between 330,000 and 400,000 soldiers from nine armies (

jun

) against 50,000 to 150,000 Vietnamese soldiers.

147

China did achieve its military objectives when it seized Lang Son on March 4 and then announced its intent to withdraw its forces, which was completed on March 16. Despite possessing a significant numerical advantage, China paid a high price for these limited gains, with 7,915 killed and another 23,298 wounded.

148

Moreover, Chinese forces advanced much more slowly than they had anticipated. Lang Son is only fifteen to twenty kilometers from the border but required sixteen days to capture. Thus, the invasion

revealed significant deficiencies in the PLA’s combat effectiveness when compared with its last major offensive operations in the Korean War against an even stronger adversary.

149

The reasons for the PLA’s poor performance have been described elsewhere, but they include poor leadership and coordination at the tactical level created by the large numbers of new soldiers and cadres with little or no military training along with the organizational upheaval of expanding units to bring them to full strength in a short period of time.

150

More generally, the PLA’s poor performance reflected the decline in readiness and training during the Cultural Revolution, when the PLA focused on garrison duties, local governance, and sideline production, as described in the previous chapter.

However, China’s poor performance in the war was not a primary factor in the decision to adopt a new military strategy in October 1980. First, although the PLA high command may have hoped that sheer numerical superiority would have produced a rapid victory in 1979, they were well aware of the PLA’s many problems. In June 1975, Deng had described the PLA as “swollen, scattered, arrogant, extravagant, and lazy.”

151

In December 1977, the CMC affirmed Mao’s “active defense, luring the enemy in deep” to stabilize the force internally in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution while restarting military training. Even the invasion itself was postponed for a month after the PLA leadership conducted an inspection tour that uncovered significant deficiencies.

152

The commander of Chinese forces on the western front, Yang Dezhi, would even be promoted to replace Deng as the chief of staff a year later. Nevertheless, the force may have performed even more poorly than senior military officers had expected, and, in this way, the war may have further emphasized the importance of improving the quality of the force that was part of the 1980 strategy, especially the emphasis on military training.

Second, senior military officers advocated for China to change its military strategy well before the February 1979 invasion. As described earlier, Su Yu and Song Shilun both pushed to change China’s strategy during and after the December 1977 CMC meeting that reaffirmed luring in deep. Su Yu’s now famous lecture on how to deal with a Soviet invasion was delivered in early January 1979, a month before the invasion. More than any other single event, the content of Su’s lecture played a clear and direct role in the content of the 1980 strategy. The lecture summarized arguments and ideas that he had developed over the past five years and was not a response to how the PLA might perform in the pending attack.

Third, available sources on the adoption of the 1980 strategy contain few references to the PLA’s poor performance in 1979. The senior officer seminar in September and October 1980 focused on how to counter what was the greatest threat to China (a Soviet attack), how such an attack would occur, how China should respond, and whether luring the enemy in deep remained the

best approach. The 1979 war may have been discussed, but does not appear to have been prominent. Planning and preparations for the meeting from May to August 1980 also contain no references to the war in available sources. The PLA did conduct a critical self-assessment of its performance, but it appears to have focused on tactical proficiency and political work.

153

Finally, the 1979 invasion was not the type of conflict that might prompt the PLA to reconsider its approach to defending against an invasion by a much stronger enemy. From China’s point of view, the 1979 invasion was a limited war, intended to teach Vietnam “a lesson.” Many of the challenges the PLA encountered in the war were exacerbated by the requirements of conducting large-scale offensive operations that had not been executed for decades. The goal of the new strategy, however, was to slow or halt an invasion. If anything, Vietnam’s defense against the invasion may have been more enlightening for the PLA as it considered the Soviet threat.

Implementation of the New Strategy

The PLA began to implement the new strategy almost immediately. New combat regulations and a campaign outline were drafted, three million troops were cut and the force reorganized, and military education and training were revitalized. The implementation of the 1980 strategic guideline not only underscores that it constituted a major change in China’s military strategy, but also that the organizational changes to implement the strategy were consistent with the factors that prompted the change in the first place—a significant shift in the conduct of warfare, amid concerns about the Soviet threat.

OPERATIONAL DOCTRINE

Consistent with a major change in strategy, the PLA initiated substantial revisions to its operational doctrine. In 1982, the PLA began to draft the “third generation” of combat regulations. The previous generation of combat regulations had been issued on only a trial basis between 1975 and 1979 and had taken almost a decade to write due to the Cultural Revolution. As one Chinese military scholar describes, “The content of the [second generation] combat regulations ‘gave prominence to politics.’ ”

154

The drafting of the third generation of combat regulations, therefore, constituted “a restoration period,” given the absence of operational doctrine during the Cultural Revolution.

155

In an effort to improve standardization of operational doctrine, the CMC established a review group headed by Han Huaizhi, a deputy chief of staff, to examine the regulations for combined arms and infantry operations along with the

Science of Campaigns Outline

(

zhanyixue gangyao

) that AMS was drafting.

15

6

More than thirty regulations were issued as part of the third generation of combat regulations. These included general regulations along with sixteen regulations for the ground forces, ten for the navy, five for the air force, and four for the rocket force. For the first time, they bore the signature of the CMC chairman, indicating the importance attached to their promulgation.

157

The

Liberation Army Daily

described the new regulations as “correctly implementing the CMC’s strategic guideline of active defense” and “absorbing the experiences of recent local wars in the world and our counterattack in self-defense against Vietnam.”

158

At the level of strategic guidance, an authoritative textbook notes that these regulations reflected the shift from luring in deep to active defense, or the 1980 strategic guideline.

159