Banking and finance

The Medici family (1397–1494)

13th century Scholastic writers condemn usury.

1873 British journalist Walter Bagehot urges the Bank of England to act as “lender of last resort” to the banking system.

1930 The Bank for International Settlements is founded in Basel, Switzerland, leading to international rules of banking regulation.

1992 US economist Hyman Minsky publishes The Financial Instability Hypothesis, which has proved useful in explaining the 2007–08 financial crisis.

Humans have long engaged in borrowing and lending. There is evidence that these activities took place 5,000 years ago in Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq) at the very dawn of civilization. But modern banking systems did not emerge until the 14th century in northern Italy.

The word “bank” comes from the Italian word for the “bench” on which the bankers sat to conduct business. In the 14th century the Italian peninsula was a land of city-states that benefited from the influence and revenue of the papacy in Rome. The peninsula was ideally located for trade between Asia, Africa, and the emerging nations of Europe. Wealth began to accumulate, especially in Venice and Florence. Venice relied on sea power: institutions were created there to finance and insure voyages. Florence focused on manufacturing and trade with northern Europe, and here merchants and financiers came together at the Medici Bank.

"A banker is a fellow who lends you his umbrella when the sun is shining, but wants it back the minute it begins to rain."

Mark Twain

US author (1835–1910)

Florence was already home to other banking families, such as the Peruzzi and the Bardi, and to different types of financial bodies—from pawnbrokers, who lent money secured by personal belongings, to local banks that dealt in foreign currencies, accepted deposits, and lent to local businesses. The bank founded by Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici in 1397 was different.

The Medici Bank financed long-distance trade in commodities such as wool. It differed from existing banks in three ways. First, it grew to a great size. In its heyday under the founder’s son, Cosimo, it ran branches in 11 cities, including London, Bruges, and Geneva. Second, its network was decentralized. Branches were managed not by an employee but by a local junior partner, who shared in the profits. The Medici family in Florence were the senior partners, watching over the network, earning most of the profit, and retaining the family trademark, which symbolized the bank’s sound reputation. Third, branches took in large deposits from wealthy savers, multiplying the lending that could be given out for a modest amount of initial capital, and so multiplying the bank’s profits.

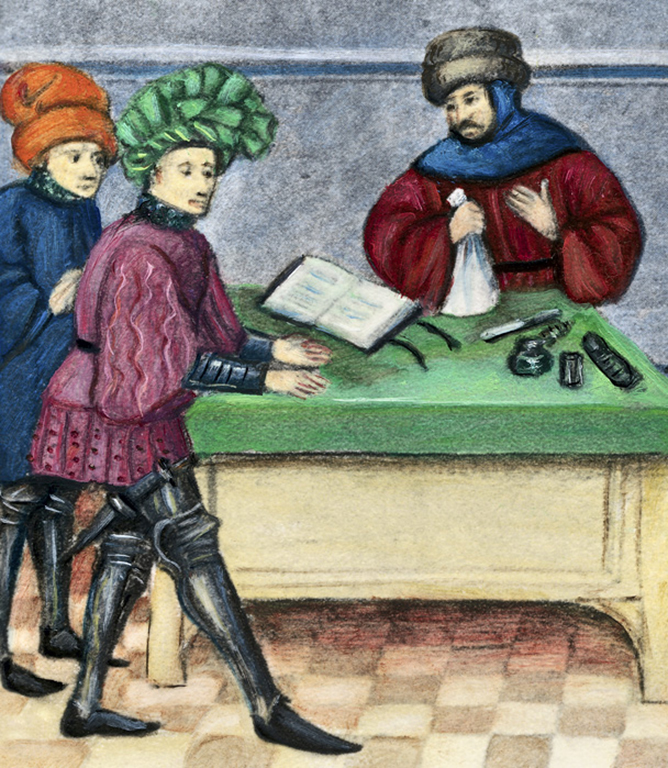

Merchant bankers of the late 14th century arranged deposits and loans but also converted foreign currencies and watched over the circulation for signs of forged or forbidden coins.

These elements of the Medici success story correspond to three economic concepts highly relevant to banking today. The first is “economies of scale.” It is expensive for an individual to draw up a single legal loan contract, but a bank can draw up 1,000 such contracts at a fraction of the “per-contract” cost. Dealings in money (cash investments) are suitable for economies of scale. The second is “diversification of risk.” The Medicis lowered the risk of bad lending by spreading their lending geographically. Moreover, because the junior partners shared in profits and losses, they needed to lend wisely—in effect they took on some of the Medici risks. The third concept is “asset transformation.” Merchants might want to deposit earnings or borrow money. One merchant might want a safe place to store his gold, from where he can withdraw it quickly if necessary. Another might want a loan—which is riskier for the bank and may tie up money for a longer time. So the bank came to stand between the two needs: “borrowing short, and lending long.” This suited everybody—the depositor, the borrower, and of course the bank, which used customer deposits as borrowed money (“leverage”), to multiply profits and make a high return on its owners’ invested capital.

However, this practice also makes the bank vulnerable—if a large number of depositors demand their money back at the same time (in “a run on the bank”), the bank may be unable to provide it because it will have used the depositors’ money to make long-term loans, and it retains only a small fraction of depositors’ money in ready cash. This risk is a calculated one, and the advantage of the system is that it usefully connects savers and borrowers.

Financing long-distance trade was a high-risk business in 14th-century Europe. It involved time and distance, so it suffered from what has been called the “fundamental problem of exchange”—the danger that someone will run off with the goods or the money after a deal has been struck. To solve this problem, the “bill of exchange” was developed. This was a piece of paper witnessing a buyer’s promise to pay for goods in a specific currency when the goods arrived. The seller of the goods could also sell the bill immediately to raise money. Italian merchant banks became particularly skilled at dealing in these bills, creating an international market for money.

By buying the bill of exchange, a bank was taking on the risk that the buyer of the goods would not pay up. It was therefore essential for the bank to know who was likely to pay up and who was not. Lending—indeed finance in general—requires specialized, skilled knowledge, because a lack of information (known as “information asymmetry”) can result in serious problems. The borrowers least likely to repay are the ones most likely to ask for loans; and once they have received a loan, there are temptations not to repay. A bank’s most important function is its ability to lend wisely, and then to monitor borrowers to deter “moral hazard”—when people succumb to the temptation not to repay and default on the loan.

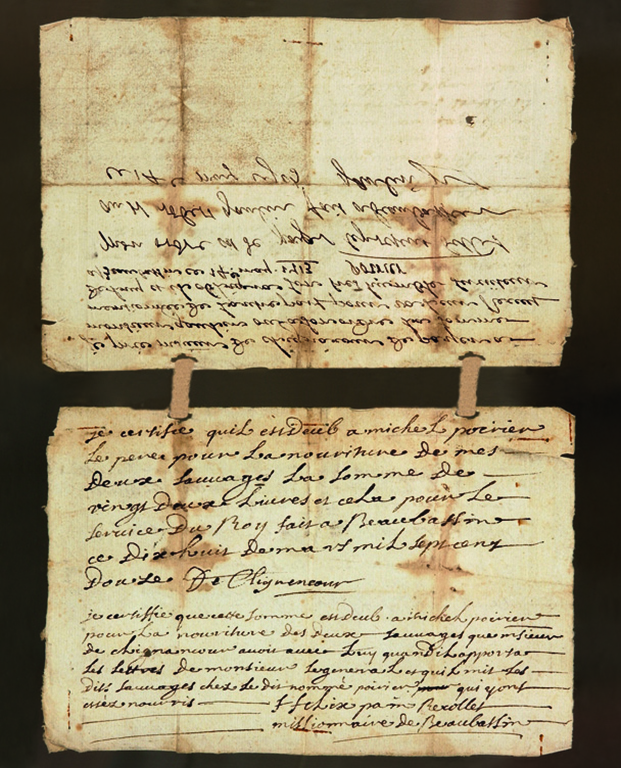

Bills of exchange, such as this one from 1713, later developed into the common bank check. All types promise to pay the bearer a specific amount of money on a certain date.

Banks often cluster together in the same place to maximize information and skill. This explains the development of financial districts in large cities. Economists call this phenomenon “network externalities,” which refers to the fact that, as a cluster starts to form, all the banks benefit from the network of deepening skills and information. Florence was one such cluster. The City of London, with its goldsmiths and shipping experts, became another. In the early 1800s the remote northern inland province of Shanxi became China’s leading financial center. Today, the internet creates new ways of clustering online.

The benefit of specialization explains why there are so many different types of banks—covering savings, mortgages, car loans, and so on. The form a bank takes can also address information problems. Mutual societies and credit unions, for instance, which are effectively owned by their customers, first arose in the 19th century to increase trust between the bank and its customers at a time of social change. Because the members of these organizations checked up on each other, and the managers had good local knowledge, they could provide the long-term loans that their customers needed. In some countries, such as Germany, they thrived. The Dutch bank Rabobank is an example of a cooperative model, as is India’s “micro-finance” Grameen Bank, which makes many loans of small amounts.

However, clustering can also lead to risky competition and crowdlike behavior. It is especially important for banks to have a good reputation because they have an asset transformation role—they transform deposits into loans—and their loan-assets are riskier, longer, and less easy to turn into cash (less “liquid”) than their deposit-liabilities.

Bad news can lead to panics. Bank failures can have severe consequences for other banks, and for government and society, as witnessed in the failure of Creditanstalt Bank in Austria in 1931, which led to a run on the German mark, UK sterling, and then the US dollar, triggering further bank runs and contributing to the Great Depression. As a result banks need to be regulated, and most countries have strict rules about who can form a bank, the information they must disclose, and the scope of their business activities.

The City of London is home to a dense cluster of banks built over medieval streets. Today it is the world’s largest center for foreign-exchange trading and cross-border bank lending.

Granting mortgages to “subprime” borrowers (people unable to repay) led to a wave of house repossessions and the financial crisis of 2007–08.

The global financial crisis, which began in 2007, has led to rethinking about the nature of banking. Leverage, or borrowed money, lay at the heart of the crisis. In 1900, about three-quarters of the assets of a bank might be financed by borrowed money. In 2007, the proportion was often 95–99 percent. The banks’ enthusiasm for placing financial bets on future movements in the market, known as derivatives, magnified this leverage and the risks it carried. Significantly, the crisis followed a period of banking deregulation. A variety of financial innovations seemed lucrative in a rising market. However, they led to poor lending standards by two groups: those providing housing loans to poor US families, and bond investors overly reliant on the advice of credit rating agencies. These are the issues faced by all banks since the Medicis: poor information, financial incentives, and risk.

Banking is just the largest part of finance, but all finance is about connecting people who have more money than they need with people who need more money than they have—and will use it productively. Stock exchanges connect these needs directly, through equities (shares conferring ownership of a company), bonds (lending that can be traded), or other instruments.

These exchanges are either physical places, such as the New York Stock Exchange, or regulated markets where trading takes place through phone calls and computers, like the international bond market. The clustering created by exchanges makes these long-term investments more liquid: they can easily be sold and turned into money. Savings can also be pooled to lower transaction costs and diversify risks. Mutual funds, pension funds, and insurance companies all perform this role.

See also: Public companies • Financial engineering • Market uncertainty • Financial crises • Bank runs