Banking and finance

Douglas Diamond (1953–)

Philip Dybvig (1955–)

1930–33 One third of all US banks fail, leading to the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to insure depositors’ money.

1978 US economic historian Charles Kindleberger publishes a landmark study of bank runs, Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises.

1987–89 At the peak of the decade-long US savings and loan crisis, US bank failures rise to a level of 200 per year.

2007–09 Thirteen countries across the world experience systemic banking crises.

During the Great Depression of the early 1930s some 9,000 US banks failed—a third of the total. However, it was not until the 1980s that economic theory came to grips with basic questions such as why banks exist, and what causes a bank run—where depositors panic and rush to withdraw their money from banks they think are at risk of failing. The article that started the debate was Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity, written in 1983 by US economists Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig. They showed that even healthy banks can suffer from a bank run and go bust.

"A bank run in our model is caused by a shift in expectations, which could depend on almost anything."

Douglas Diamond, Philip Dybvig

Diamond and Dybvig made a mathematical model of an economy to demonstrate how bank runs occur. Their model has three points in time—such as Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday—and assumes that there is only one good or product available to people, which they can consume or invest.

"If any bank fails, a general run upon the neighbouring banks is apt to take place, which if not checked in the beginning by a pouring into the circulation of a very large quantity of gold, leads to extensive mischief."

Henry Thornton

UK economist (1760–1815)

Each person starts off with a certain amount of the good. On Monday people can do two things with their good: they can store it, in which case they get back the same amount on Tuesday to consume; or they can invest it. If they choose to invest the good, which is only possible on Monday, they will receive much more of it back on Wednesday. However, if they cash in the investment early on Tuesday, they will receive less than they invested. These investments, which are made for a set period, are what is known as “illiquid” investments. This means that they cannot easily be transformed into ready cash, as liquid assets can.

Banks only keep a relatively small percentage of their deposits in cash reserves. If all a bank’s depositors turn up to demand their money back on the same day, only those at the front of the line will receive their money.

Diamond and Dybvig assume there are two types of people: patient people, who want to wait until Wednesday, when they can consume more, and impatient people, who want to consume on Tuesday. However, people do not discover which type of person they are until Tuesday. The decision that people face on Monday is how much to store and how much to invest. The only uncertainty in the model is whether these people are patient or impatient. Banks might have a good idea about probabilities: in general, 30 percent of people might prove to be impatient and 70 percent patient. So it is possible that people will store and invest amounts that reflect these proportions. But whatever people choose, it will never be the most efficient outcome overall because impatient people should never invest, and patient people should not store anything. A bank can solve this problem. We can think of a bank in this model as a place where people all agree to pool their goods and share risks. The bank gives people a deposit contract and then itself invests and stores the goods in bulk.

The deposit contract offers a higher return than storage and a lower return than investment, and allows people to withdraw their goods from the bank on either Tuesday or Wednesday with no penalty. Having pooled people’s goods, the bank, knowing the share of patient and impatient people, can then store enough of the good to cover the needs of impatient people and invest enough to cover the wants of patient people. In the Diamond–Dybvig model this is a more efficient solution than people could reach independently because with large numbers, the bank can do this in a way that the individual cannot.

On Tuesday the bank has illiquid assets—the patient people’s investment that will reap a return on Wednesday. At the same time it has to pay the impatient people their deposits right away. Its ability to do this is the reason for its existence. Diamond and Dybvig showed that this property also makes the bank vulnerable to a run. A run occurs when, on Tuesday, patient people become pessimistic about what they will receive from the bank on Wednesday, and so withdraw their deposits on Tuesday. Their actions mean that the bank must sell investments at a loss; it will not have the resources to pay all of its patient and impatient customers, and those later in the line will not receive anything. Knowing this, customers become eager to be at the front of the line.

Pessimism can arise out of concerns about investments, other people’s withdrawals, or the bank’s survival. Crucially, this allows for the possibility of a self-fulfilling bank run even if the bank is sound. For instance, suppose that on Tuesday I believe that other people are going to withdraw their deposits—I then decide to do so as well because I fear that the bank may fail. Then suppose that many other people think in the same way that I have. This itself can cause a run on the bank, even if the bank would otherwise be able to meet its obligations today and tomorrow. This is an example of what economists call “multiple equilibrims”—more than one outcome. Here there are two outcomes: a “good” one in which the bank survives and a “bad” one in which it is sunk by a run. Where we end up may depend on the people’s beliefs and expectations rather than the true health of the bank.

A panicking crowd is held back by police outside a German bank in 1914. The declaration of war had caused pessimism among savers, leading to a number of bank runs.

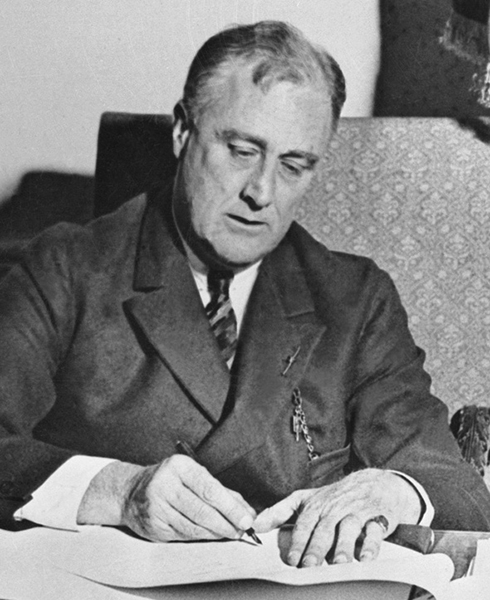

Diamond and Dybvig showed how governments could alleviate the problem of bank runs. Their model was partly a defense of the US’s system of federal deposit insurance, under which the state guarantees the value of all bank deposits up to a specified amount. Introduced in 1933, this system reduced bank failures. In March, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt also declared a national bank holiday to prevent people from withdrawing their savings. Alternatively, the central bank can act as the “lender of last resort” to banks. However, there is often uncertainty about what the central bank will do. Deposit insurance is ideal, because it ensures that patient people will not participate in a bank run.

"By the afternoon of March 3, scarcely a bank in the country was open to do business."

Franklin D. Roosevelt

In 1933, President Roosevelt signed an act that guaranteed bank deposits. Bank runs were reduced, but some believe that such deposit guarantees increase risk taking.

There are alternative explanations for the existence of banks. Some focus on banks’ investment role. The bank can gather and keep private information about investments, choosing between good and bad investments, and reflect this private information efficiently through the returns it offers to savers. It can offer a return to depositors that is only possible if it carries out its monitoring role well.

In 1991, US economists Charles Calomiris and Charles Kahn published an article that took issue with the Diamond–Dybvig view. They argued that bank runs are good for banks. In the absence of deposit insurance, depositors have an incentive to keep a close eye on how well their bank performs. The threat of a run also provides an incentive to the bank to make safe investments. This is one side of so-called “moral hazard”. The other side is that managers will take riskier decisions than they would if there were no deposit insurance. The problem of moral hazard became apparent in the 1980s US savings and loan crisis, when mortgage lenders were allowed to make riskier loans and deposit insurance was enhanced. US bank failures rose.

It is hard to prove which of these two views about bank runs is correct, since in practice neither explanation can be isolated. There are many forms of moral hazard in a bank. A shareholder may encourage risk taking because all he can lose is his investment. A bank employee, offered bonus incentives, may take risks because all that is at stake is a job. One commonly proposed solution to moral hazard is tougher regulation.

"In the history of modern capitalism, crises are the norm, not the exception."

Nouriel Roubini, Stephen Mihm

Recent bank crises have usually begun with investment losses. Banks are forced to sell assets to reduce their borrowing. This leads to further falls in asset prices and further losses. A run on deposits follows, which can spread to other banks to become a panic. If the whole banking system is affected, it is called a systemic banking crisis. In the 2007–08 crisis, runs occurred despite the system of deposit insurance. A large part of the recent crisis took place institutions that are not regulated as banks, such as hedge funds, but were doing much the same as a bank: borrowing for short terms and lending for long terms.

Many countries strengthened their deposit insurance policies during the financial crisis that began in 2007–08. This is understandable, since bank failures can have a devastating effect on the real economy, breaking the connection between people with savings and people who need to invest. The moral hazard argument is like fire prevention, in that it is concerned with protecting the economy from a future crisis. However, the midst of a crisis may not be the time to be talking about preventative actions.

In September, 2007, the first serious British bank run since 1866 took place. Northern Rock, Britain’s eighth-largest bank, was a fast-growing mortgage lender. To expand its business, it had become over-reliant on “wholesale” funding—funding provided by other institutions—rather than personal deposits. When wholesale financial markets froze on August 9, 2007, a gradual, unseen wholesale run began. At 8:30 p.m. on Thursday, September 13, BBC Television News reported that the UK central bank, the Bank of England, would announce emergency liquidity support the next day.

It emerged later that Mervyn King, the Governor of the Bank of England, had opposed a rescue offer by Lloyds, another British bank. King had suggested that central bank support might reassure depositors. However, this reassurance did not happen, and a run on personal deposits began over the internet that evening. Under Britain’s deposit insurance program, deposits above $3,300 (£2,000) were not fully insured, and the next day, long lines formed outside Northern Rock branches. The run ended the following Monday evening after the government announced a guarantee for all deposits.