Theories of value

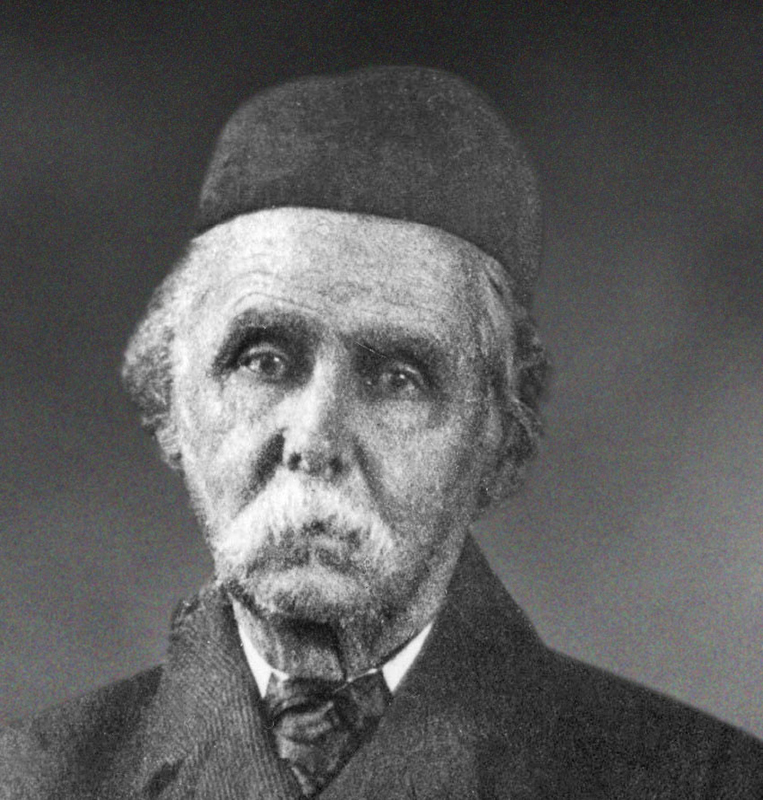

Alfred Marshall (1842–1924)

c.1300 Islamic scholar Ibn Taymiyyah publishes a study of the effects of supply and demand on prices.

1691 English philosopher John Locke argues that commodity prices are directly influenced by the ratio of buyers to sellers.

1817 British economist David Ricardo argues that prices are influenced mainly by the cost of production.

1874 French economist Léon Walras studies the equilibrium (balance) in markets.

1936 British economist John Maynard Keynes identifies economy-wide total demand and supply.

Supply and demand are among the fundamental building blocks of economic theory. The interplay between the amount of a product available on the market and the eagerness of consumers to buy that product creates the foundation of markets.

The importance of supply and demand in economic relationships was studied as long ago as the Middle Ages. The medieval Scottish scholar Duns Scotus recognized that a price must be fair to the consumer but must also take into account the costs incurred in production and therefore be fair to the producer. Subsequent economists studied the effects of supply-side costs on eventual prices, and economists such as Adam Smith and David Ricardo linked the price of a product to the labor required in its production. This is called the classical labor theory of value.

In the 1860s new economic theories began to develop, challenging these ideas under the banner of the neoclassical school. This school of thought introduced the theory of marginal utility, where the satisfaction a consumer gains or loses from having more or less of a product affects both demand and price.

British economist Alfred Marshall joined the analysis of supply with the new neoclassical approach to demand. Marshall saw that supply and demand work in tandem to generate the market price. His work was important because he illustrated the varying dynamics of supply and demand in short-term markets (such as those for perishable goods), as opposed to long-term ones (such as for gold). He applied mathematics to economic theories and produced the “Marshallian Cross:” a graph showing supply and demand as crossing lines. The point at which they intersect is the “equilibrium” price, which perfectly balances the needs of supply (the producer) and demand (the consumer).

"In every case the more of a thing is offered for sale in a market, the lower is the price at which it will find purchasers."

Alfred Marshall

This graph, known as the Marshallian Cross, shows the relationship between supply and demand. The point at which the supply and demand curves intersect gives the price.

The amount of products a firm chooses to produce is determined by the price at which it can sell them. If the assorted costs of production (labor, materials, machines, and premises) amount to more than the market is willing to pay for the product, production will be seen as unprofitable and be reduced or stopped. If, on the other hand, the market price for the item is substantially more than the costs of production, the company will seek to expand production to make as much profit as possible. The theory assumes that the firm has no influence over the market price and must accept what the market offers.

For example if the costs of producing a computer amount to $200, production will be unprofitable if the market price of the computer drops under $200. Conversely, if the market price of the computer is $1,000, the firm producing it will seek to produce as many as possible to maximize profits. The law of supply can be visualized using a supply curve, where every point of the curve provides the answer to how many units a firm will be willing to sell at a particular price.

Furthermore, there must be a distinction between fixed and variable costs. The above example assumes that production can be increased with the unit cost of production remaining stable. However, this is not the case. If the computer factory can produce only 100 machines per day, yet there is demand for 110, the producer must judge whether it makes sense to open a completely new factory, with the vast additional costs this incurs, or whether it makes more sense to sell the computers at a slightly higher price to reduce demand to only 100 per day.

The law of demand sees matters from the viewpoint of the consumer rather than the producer. When the price of a good increases, demand inevitably falls (except for essential goods such as medicines). This is because some consumers will no longer be able to afford the item, or because they decide that they can gain more enjoyment by spending the money elsewhere.

Using the same example as previously, if the computer costs only $50, the volume of sales will be high since most people will be able to afford one. On the other hand if it costs $10,000, the demand will be very low, since only the very wealthy will be able to afford them. As prices increase, demand falls.

There is a limit to how low prices can fall to stimulate demand. If the price of the computer falls to below $5, everyone will be able to afford to buy one, but nobody needs more than two or three computers. Consumers realize that their money is better spent on something else, and demand flattens out.

Price is not the only factor that affects demand. Consumer tastes and attitudes are also a major factor. If a product becomes more fashionable, the whole demand curve shifts to the right; consumers demand more of the product at each price. Given the static position of the supply curve, this drives up the price. Because consumer tastes can be manipulated through techniques such as advertising, producers can influence the shape and position of the demand curve.

Producers of goods such as Coca-Cola may influence demand through advertising that promotes the product and the brand. As demand rises, the price of the product may also rise.

While consumers will always seek to pay the lowest price they can, producers will look to sell at the highest price they can. When prices are too high, consumers lose interest and move away from the product. Conversely, if prices are too low, it no longer makes financial sense for the producer to continue to make the product. A happy medium must be reached—an equilibrium price acceptable to both consumer and producer. This price is found at the point where the supply curve intersects the demand curve, producing a price at which consumers are happy to pay and producers are happy to sell.

"When the demand price is equal to the supply price, the amount produced has no tendency either to be increased or to be diminished; it is in equilibrium."

Alfred Marshall

Many factors complicate these relatively simple laws. The position and size of the market are crucial in price determination, as is time. The price at which producers are happy to sell is not just influenced by the costs of production.

For instance, consider a market stall selling fresh produce. The farmer arrives having already paid for the costs of production, buying the seeds, the labor involved in planting and harvesting the crop, and his transport to the market. He knows that to make a profit, he must sell each apple for $1.20. Therefore, at the start of the day, he decides to market his apples at $1.20. If his sales are going well, he may feel he can make more money and raise his price to $1.25. This may cause a slowdown in sales, but if he manages to sell his entire stock, he will be happy. However, if the end of the day is nearing and he finds that he still has quite a few apples left, he might decide to drop his price to $1.15 to avoid being left with an excess of apples that are likely to rot before his next chance to sell them.

In this example the costs of production are fixed, and the urgency of selling the crop is the pressing factor. This is useful in illustrating the differences between short- and long-term markets. The farmer will decide how many apples to plant for his next harvest, based on his sales this time, and in this way the market should eventually arrive at equilibrium.

The farmer’s market is also limited by distance. There is only a certain radius within which it makes economic sense to sell his products. For instance the cost involved in shipping his apples overseas would make his prices uncompetitive with domestic producers. This means that, to some extent, the farmer is at liberty to set his prices slightly higher because his customers cannot travel to seek alternatives.

"The price of any commodity rises or falls by the proportion of the number of buyers and sellers… [this rule] holds universally in all things that are to be bought and sold."

John Locke

The opposite scenario to the fruit farmer is the market for a global commodity such as gold. In this long-term market the holder of the gold is under no time pressure to sell. He can be confident that it will maintain its value. The larger the market and the more widespread the knowledge of the market, the more likely it is that the commodity has found its equilibrium price. This makes any small change in market price significant, and any change will spark a flurry of buying and selling.

Although these examples introduce further complexity into the market, they hold true to the basic rule that suppliers will only sell at a price they find acceptable, while buyers will only buy at a price they find reasonable.

The examples all relate to a market in which physical goods are traded, but supply and demand is relevant throughout economic reasoning. The model is applicable to the labor market, for instance. Here the individual is the supplier, selling his or her labor, and employers are the consumers, looking to buy labor as cheaply as possible. Money markets are also analyzed as a supply and demand system, with the interest rate acting as the price.

Economists call Marshall’s work “partial equilibrium” analysis because it shows how a single market reaches equilibrium or balance through the forces of supply and demand. However, an economy is made up of many different interacting markets. The question of how all these can come together in a state of “general equilibrium” is a complex problem that was analyzed by Léon Walras in the 19th century.

Fruit sellers may have to throw away any unsold apples at the end of the day. The urgency to sell in time is a major factor in determining the price at which to sell perishable goods.

Born in London, England, in 1842, Alfred Marshall grew up in the borough of Clapham before going to Cambridge University on a scholarship. There, he studied mathematics and then metaphysics, concentrating on ethics. His studies led him to see economics as a practical means of implementing his ethical beliefs.

In 1868, Marshall took up a lectureship specially created for him in moral science. His interest in this continued until a visit to the US in 1875 made him focus more on political economy. Marshall married Mary Paley, his former student, in 1877 and became principal of University College, Bristol, UK. In 1885, he returned to Cambridge as professor of political economy, a post he held until his retirement in 1908. From about 1890 until his death in 1924, Marshall was considered the dominant figure in British economics.

1879 The Economics of Industry (with Mary Paley Marshall)

1890 Principles of Economics

1919 Industry and Trade