Economic systems

Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973)

1867 Karl Marx sees scientific socialism as organized like an immense factory.

1908 Italian economist Enrico Barone argues that efficiency can be achieved in a socialist state.

1929 US economist Fred Taylor says that mathematical trial and error can achieve equilibrium under socialism.

1934–35 Economists Lionel Robbins and Friedrich Hayek emphasize the practical problems with socialism—such as the scale of computation required and the absence of risk taking.

The German philosopher Karl Marx described socialist economic organization in his great work Capital in 1867. A socialist economy, he argued, required state ownership of the means of production (such as factories). Competition was wasteful. Marx proposed running society as if it were one enormous factory and believed that capitalism would lead inevitably to revolution.

Economists took Marx’s ideas seriously. When Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto used mathematics to demonstrate how free market competition produces efficient outcomes, he also suggested that these could be achieved by a central planner under socialism. His compatriot, the economist Enrico Barone, took this notion further in The Ministry of Production in a Collectivist State (1908). Just a few years later, Europe was engulfed by World War I, which many saw as a catastrophic failure of the old order. The Russian Revolution of 1917 provided an example of a socialist takeover of the economy, and the war’s defeated powers—Germany, Austria, and Hungary—saw socialist parties take power.

Free market economists seemed unable to offer theoretical counter-arguments to socialism. But then in 1920, Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises raised a fundamental objection, claiming that planning under socialism was impossible.

Von Mises’ 1920 article Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth carried a simple challenge. He said that production in the modern economy is so complex that the information provided by market prices—which is generated through the rivalry of many producers focused on making profits—is essential to planning. We need prices and profits to establish where demand lies and guide investment. His ideas started a debate between capitalism and socialism, called the “socialist calculation“ or “systems debate.”

"In the socialist commonwealth, every economic change becomes an undertaking whose success can be neither appraised in advance nor later retrospectively determined. There is only groping in the dark."

Ludwig von Mises

Imagine planning a railway between two cities. Which route should it take, and should it even be built at all? These decisions require a comparison of benefits and costs. The benefits are savings in the transport expenses of many different users. The costs include labor hours, iron, coal, machinery, and so on. It is essential to use a common unit to make this calculation: money, the value of which is based on market prices. Yet, under socialism, genuine money prices for these items no longer exist—the state has to make them up. Von Mises said that this was not as much of a problem for consumer goods. It is not difficult to decide, based on consumer tastes, whether to devote land to producing 1,000 gallons of wine or 500 gallons of oil. Nor is it a problem for simple production, as in a family firm. One person can easily make a mental calculation as to whether to spend the day building a bench, making a pot, picking fruit, or building a wall. However, complex production requires formal economic calculation. Without such help, von Mises claimed, the human mind “would simply stand perplexed before the problems of management and location.”

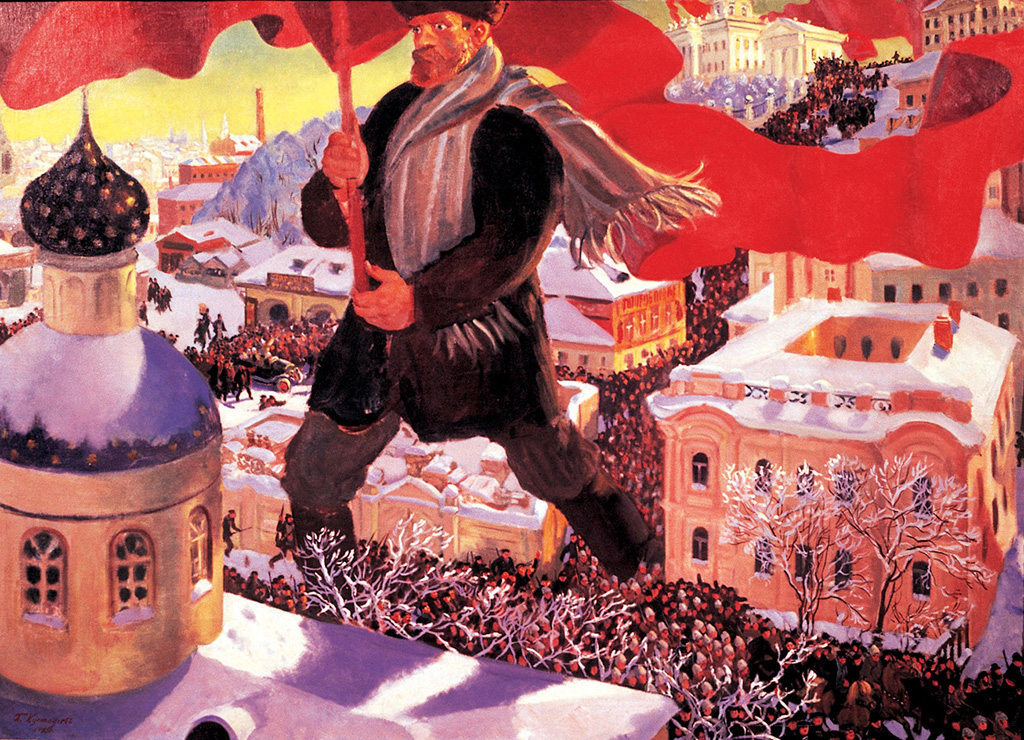

Boris Kustodiev’s The Bolshevik reflected the idealistic policies of the Russian Revolution. Within four years they had floundered and were replaced by the New Economic Policy.

In addition to using money prices as a common unit with which to evaluate projects, economic calculation under capitalism has two other advantages. First, market prices automatically reflect the valuations of everyone involved in trade. Second, market prices reflect production techniques that are both technologically and economically feasible. Rivalry among producers means only the most profitable production techniques are selected.

Von Mises argued that genuine market prices rely on the existence of money, which must be used at all stages—for buying and selling the goods involved in production, and for buying and selling them in consumption. Money is used in a more limited way in the socialist system: for paying wages and buying consumer goods. But money is no longer needed at the state-owned production end of the economy, just as it is not needed for the internal workings of a factory. Von Mises considered alternatives to money, such as Marx’s idea of valuing products by the number of hours of labor that have gone into making them. But such a measure ignores the relative scarcity of different materials, the different qualities of the labor, or the actual (as opposed to labor) time that the production process takes. Only market prices take all these factors into account.

Von Mises, and his followers in the Austrian School of economists, did not believe that societies reach equilibrium, where they “naturally” hover around a certain level, or state of balance. He argued that economies are in constant disequilibrium; they are always changing, and participants are surrounded by uncertainty. Furthermore, a central planner cannot simply adopt the prices that previously prevailed under a market system. If central planning relies on prices from a different system, how could socialism possibly supersede the market economy?

Von Mises’s challenge sparked several responses. Some economists claimed that a central planner could equate supply and demand through trial and error, similar to the process that Léon Walras had suggested for establishing equilibrium in a market economy. However, this mathematical approach was really no different from the arguments of Barone, and any discussion of mathematical equilibrium was considered unrealistic by the Austrian School.

Von Mises’s supporters, Lionel Robbins and Friedrich Hayek, added that such computation was not practical. Moreover, the socialist system could not replicate the risk taking in the face of uncertainty undertaken by entrepreneurs in the market system. In 1936, economists Oskar Lange and Abba Lerner proposed a system of “market socialism” whereby many separate firms are owned by the state and seek to maximize profits, given prices set by the state. Hayek, the Austrian School’s new champion, led the response to market socialism, arguing that only the free market could provide the necessary incentives and information.

Planned economies lack basic market information about demand, so a central planning committee has to guess the type and level of demand for any item. Their ideas about what people want or need are unlikely to be accurate.

For some of its life the Soviet Union operated a form of market socialism. At first it appeared to do well, but the economic system suffered from persistent problems. There were periodic attempts at reform, shifting targets from output to sales, and trying to give more discretion to state firms. But state firms often hid resources from central planners, met targets through shortcuts that did not meet customer needs, and neglected tasks outside their plans. There was considerable waste, and output fell well short of targets. When the system collapsed, the Austrian School’s concerns about incentives and information seemed to have been justified by events.

Von Mises was equally critical of any form of government intervention in the market economy. He claimed that intervention produces adverse side effects that lead to further intervention until, step-by-step, society is led into full-blooded socialism. In the market economy firms make profits by serving consumers, and in his opinion—and that of the Austrian School—there should be no restrictions on such a worthwhile activity.

The Austrian School does not accept the concept of market failure, or at least sees it as trumped by government failure. It believes monopoly is caused by governments rather than by private enterprise. Externalities (outcomes that are not reflected in market prices) such as pollution are taken into consideration by consumers or solved by voluntary associations or the responses of people whose property rights are affected by the externality.

For the Austrian School one of the worst forms of government intervention is interference in the money supply. They claim that when governments inflate the supply of money (by printing more money, for example) it leads to interest rates that are too low, which in turn result in bad investments. The only thing to do when a bubble bursts is to accept the commercial failures and ensuing depression. They recommend abolishing central banks and basing money on a real commodity standard, such as gold. The Austrian School are firm believers in laissez-faire (hands-off) government.

In 1900, there were five leading schools of economics. Marxism, the German Historical School (which was also critical of the market system), and three versions of the mainstream free market approach: the British School (led by Alfred Marshall), the Lausanne School (centered on general equilibrium through mathematical equations), and the Austrian School, led by Carl Menger. The British and Lausanne schools became mainstream economics, but the Austrian School trod an uncompromising path. Only recently, following the 2008 financial crisis and the retreat of socialism, has it begun to grow in popularity.

Socialist economies saw themselves as vast production lines, assembling everything the economy needed. During World War II this command style of production line worked relatively efficiently.

The leader of the Austrian School, Ludwig von Mises was the son of a railway engineer. He was born in Lemberg, Austria–Hungary, in 1881 and studied at the University of Vienna, where he regularly attended the seminars of the economist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk. From 1909–34, von Mises worked at the Vienna Chamber of Commerce, serving as principal economic adviser to the Austrian government. At the same time he also taught economic theory at the university, where he attracted a dedicated following but never became professor. In 1934, concerned by Nazi influence in Austria, he took a professorship at the University of Geneva. In August, 1940, shortly after the German invasion of France, he emigrated to New York and taught economic theory at New York University from 1948–67. He died in 1973.

1912 The Theory of Money and Credit

1922 Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis

1949 Human Action: A Treatise on Economics