Global economy

Dani Rodrik (1957–)

1664 English economist Thomas Mun says that growth requires reductions in imports.

1817 British economist David Ricardo says that international trade makes countries richer.

1950 Raúl Prebisch and Hans Singer argue that developing countries lose out from globalization because of unequal terms of trade.

2002 Joseph Stiglitz criticizes globalization as promoted by the World Bank and the IMF.

2005 World Bank economist David Dollar argues that globalization has reduced poverty in poor countries.

Globalization is a term that means different things to politicians, business people, and social scientists. To an economist it means the integration of markets. Economists have long thought this a good thing.

In the 18th century Adam Smith attacked the old mercantilist ideas of protectionism, which aimed to restrict the inflow of foreign goods. He argued that international trade would expand the size of markets and allow countries to become more efficient by specializing in certain products. Often, market integration is seen as inevitable because it rides on the back of a wave of new technology—such as smarter phones, faster planes, and an expanding internet. But globalization is also affected by choices made by nations—sometimes conscious, sometimes accidental. Although technological change tends to bring nations together, policy choices can push them apart.

Modern globalization is not unprecedented. Globalization has waxed and waned over time as nations have made different policy choices. Sometimes these choices have added to the effect of technological progress on the integration of markets; sometimes, they have hindered it.

Market integration is the fusing of many markets into one. In one market a commodity has a single price: the price of carrots would be the same in east Paris and west Paris if these areas were part of the same market. If the price of carrots in west Paris was higher, sellers of carrots would move from the east to the west and prices would equalize. The price of carrots in Paris and in Lisbon might be different, though, and high transport costs and other kinds of expenses might mean that it would be uneconomical for Portuguese sellers to move their stocks to France if prices were higher there. In distinct markets the price of the same good can be different for long periods of time.

Global market integration means that price differences between countries are eliminated as all markets become one. One way to track the progress of globalization is to look at trends in how prices converge (become similar) across countries. When the costs of trading across borders fall, there is more potential for firms to take advantage of price differences, for Portuguese carrot sellers to enter the French market, for example. Trading costs fall when new forms of transport are invented, or when existing ones become faster and cheaper. Also, some costs are man-made: states erect barriers to trade, such as tariffs and quotas on imports. When these are reduced, the cost of international trading falls.

Christopher Columbus stumbled across the Americas on an expedition intended to find a new trade route to China. Such efforts to globalize trade have taken place for centuries.

Long-distance trade has existed for centuries, at least since the trade missions of the Phoenicians in the first millennium BCE. Such trade was driven by growing populations and incomes, which created a demand for new products. But the underlying barriers to trade that divided up markets, such as transport costs, did not change that much. Globalization only really took off in the 1820s, when price differences started to close up. This was caused by a transport revolution—the advent of steamships and railroads, the invention of refrigeration, and the opening of the Suez Canal, which slashed the journey time between Europe and Asia. By the eve of World War I the global economy was highly integrated, even by late 20th-century standards, with unprecedented flows of capital, goods, and labor across borders.

From the 19th century onward, technological change helped to integrate markets. It is this that makes globalization seem irreversible—once technology such as steam-powered transport is invented, it is not then uninvented but tends to become economically viable in more countries. Much of this development is outside the direct control of governments. However, at a stroke, governments can put up tariffs and other types of barriers to trade that choke off imports and stymie trade.

The most dramatic policy-related reversal of globalization in modern times occured during the Great Depression of the 1930s. As countries headed into recession, governments imposed tariffs. These were intended to switch the demand of their consumers toward domestically produced goods. In 1930, the US enacted the Smoot–Hawley tariff, which raised tariffs on imported goods to record levels. These tariffs reduced demand for foreign goods. Foreign countries retaliated by imposing their own tariffs. The result was a collapse in world trade that worsened the effects of the Depression. It took decades to rebuild the world economy.

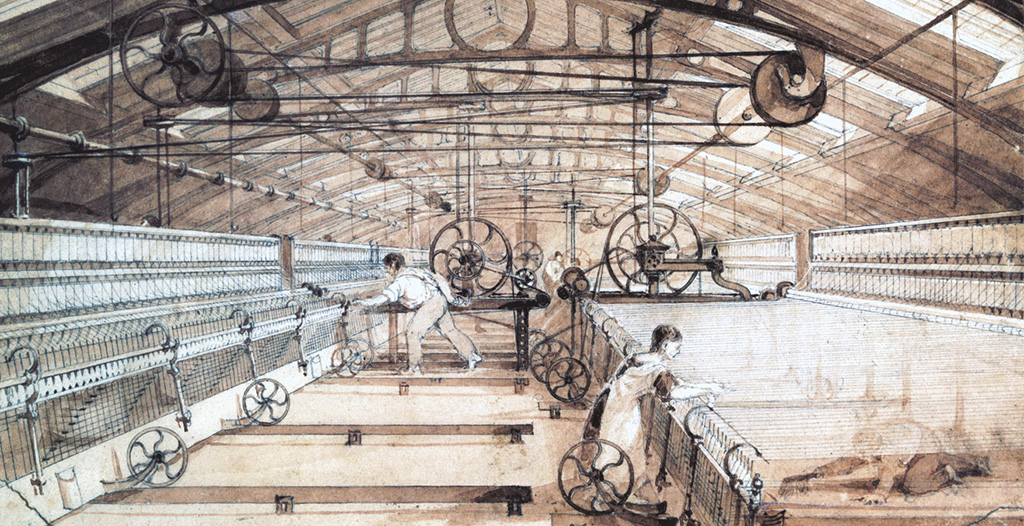

By the mid-19th century Britain had new technology such as these mechanized looms in cotton mills, which allowed it to export and compete in multiple markets around the world.

By the end of the 20th century globalization across most markets had returned to the levels seen just before World War I. Today, markets are more integrated than ever as transportation costs have continued to fall and most tariffs have been scrapped altogether.

One vision of the future of globalization involves the elimination of other kinds of barriers to trade caused by institutional differences between countries. Markets are embedded in institutions—in property rights, legal systems, and regulatory regimes. Differences in institutions between countries create trading costs in the same way that tariffs or distance do. For example, there may be different laws in Kenya and China about what happens when a buyer fails to pay. This might make it hard for a Chinese exporter to recover what it is owed in the event of a dispute, which could make the firm reluctant to enter the Kenyan market. Despite the removal of tariffs the world is far from being a single market. Borders still matter because of these kinds of institutional incompatibilities. Complete integration requires the ironing out of legal and regulatory differences to create a single institutional space.

Some economists argue that this process is underway and inevitable, and that global markets drive the harmonization of institutions across countries. Consider a multinational firm choosing a country in which to locate its factory. In order to attract the firm’s investment, a government might cut business tax rates and loosen regulatory requirements. Other competing countries follow suit. The resulting lower tax revenues make countries less able to finance welfare states and educational programs. All policy decisions become oriented toward maximizing integration with global markets. No goods or services would be provided that are incompatible with this.

Improvements in transport have been a major driver in globalization. In Shanghai, China, the US has invested in a gigantic “mega-port” that will make shipping safer.

The Turkish economist Dani Rodrik (1957–) has criticized this vision of “deep integration,” arguing that it is undesirable and far from inevitable, and that in reality considerable institutional diversity persists between countries. Rodrik’s starting point is that choices about the direction of globalization are subject to a political “trilemma.” People want market integration because of the prosperity that it can bring. People want democracy, and they want independent, sovereign nation-states. Rodrik argues that the three of these are incompatible. Only two are possible at any one time. How the trilemma is resolved implies different forms of globalization.

"… ‘deep’ economic integration is unattainable in a context where nation states and democratic politics still exert considerable force."

Dani Rodrik

The trilemma comes from the fact that the deep, or more complete, integration of markets requires the removal of institutional variations between countries. But electorates in different countries want different types of institutions. Compared to US voters, those in European countries tend to favor large welfare states. So a single global institutional framework in which nation-states still existed would mean ignoring the preferences of electorates in some countries. This would conflict with democracy, and governments would be placed in what US journalist Thomas Friedman (1953–) has called a “golden straitjacket.” On the other hand a global institutional framework in which democracy reigned would require “global federalism”—a single worldwide electorate and the dissolution of nation-states.

Today, we are far from either the golden straitjacket or global federalism. Nation-states are strong, and persistent institutional diversity across countries suggests that the varied preferences of different populations are still important. Since World War II Rodrik’s trilemma has been resolved by sacrificing deep integration. Markets have been brought together as much as possible given nations’ varied institutions. Rodrik calls this the “Bretton Woods compromise,” referring to the global institutions that were established after the war—the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). These organizations aimed at preventing a repeat of the catastrophic backlash seen in the 1930s through a form of managed integration, in which nation-states were free to pursue their own domestic policies and develop along varied institutional paths.

"The 19th century contained a very big globalization bang."

Jeffrey G. Williamson, K. H. O’Rourke

The liberalization era since the 1980s saw an undermining of the Bretton Woods compromise, with the policy agenda being increasingly driven by the aim of deep integration. Rodrik argues that institutional diversity should be preserved over deep integration. European electorates’ desire for welfare states and public health systems is not just about economics, but also their view of justice. Institutional diversity reflects these different values. More practically, there is more than one institutional route to a healthy economy. The requirements for growth in today’s developing countries may be different from those for developed nations. Imposing a global institutional blueprint runs the risk of placing countries in a straitjacket that suffocates their own economic development. Globalization may have limits, and it may be that the complete fusion of economies is neither feasible nor—ultimately—desirable.

Nations may want democracy, independence, and deep global economic integration. Yet at any one time, only two out of three may be compatible with each other. In the diagram each side of the triangle represents a possible combination.

The East Asian crisis began when the Thai government attempted to float the bhat on the international markets, ending its link to the dollar.

The liberalization of capital (money) markets, where funds for investment can be borrowed, has been an important contributor to the pace of globalization. Since the 1970s there has been a trend towards a freer flow of capital across borders. Current economic theory suggests that this should aid development. Developing countries have limited domestic savings with which to invest in growth, and liberalization allows them to tap into a global pool of funds. A global capital market also allows investors greater scope to manage and spread their risks.

However, some say that a freer flow of capital has raised the risk of financial instability. The East Asian crisis of the late 1990s came in the wake of this kind of liberalization. Without a strong financial system and a robust regulatory environment capital market globalization can sow the seeds of instability in economies rather than growth.