A huge bonfire illuminated the faces of the crowd standing before a group of uniformed speakers and the large posters that decorated the stage. Suddenly, a lit torch was thrown from one man to another and just as quickly passed from hand to hand on the stage. Cheers rose up from the assembly. The Carleton county village of Woodstock had seen preachers and circuses, frauds and temperance advocates and virtually every other public display imaginable, but this meeting in September 1916 was different.

A visitor from Fredericton was speaking, and the farmers and merchants and their families hung on every word. Colonel Percy Guthrie urged his listeners to enlist in the army and help finish off the German “Hun,” punctuating his appeal by passing the still-flaming torch to a soldier on horseback, who rode off gallantly toward the site of the next recruiting meeting. Canada’s soldiers, including New Brunswick’s own 26th Battalion, had already been covered in honour by their heroic actions at Second Ypres, where Guthrie himself had been wounded, and on the Somme: only one last push was needed to ensure victory. Didn’t the listeners wish to join up? Didn’t they remember the heritage of the Glorious Twelfth, their Loyalist forefathers and their membership in the British Empire? They did, but the people of Carleton county had other pressing concerns.

The First World War was a momentous period in Canadian history. The young country was unprepared for the scale and nature of the conflict or for the social and political upheaval it brought. More than 60,000 Canadians died and more than a quarter of a million were seriously wounded on active service, and the human wreckage of the war shaped the decades that followed. The war also brought employment, inflation, population movements, women’s suffrage, prohibition, new political organizations and closer ties with the United States, and thrust English-French, Protestant-Catholic and other majority-minority relations into the mainstream. New Brunswick’s experience illustrates the complex social impact of the war on the homefront; it also presents a different focus on the conscription crisis than that of the Ontario-Quebec battle that so dominates accounts of the period.

Canadian histories of the First World War focus on the military accomplishments of the Canadian Corps, on the growth of Canada from “colony to country” on the world stage and on conscription. Since conscription so openly divided French and English Canada, the issue remains relevant to Canadian problems today. The history of conscription in the Great War, however, has been shaped by the debate over Quebec nationalism and has focused almost exclusively on how conscription was viewed in francophone Quebec and anglophone Ontario. But the war had a profound impact on all regions of Canada: few communities in this vast land escaped unscathed.

When the war began, Canada was stable, wealthy and far removed from the problems of the world, circumstances that attracted many immigrants to Canadian shores: in 1913 alone, 400,000 newcomers joined a population of just eight million people. Most Canadians lived in rural communities, mainly villages or small towns, and dispersed across the landscape on small family farms. Only Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia had majority urban populations — although, significantly, the francophone populations of the two central provinces remained largely rural. The other six provinces, among them New Brunswick and its 352,000 people, were predominantly rural. Yet historians of the war have tended to overlook the reactions of Canada’s rural majority and of Canadians who were neither British nor French. Small, rural, poor and with a significant Acadian population, New Brunswick offers a different perspective on francophone and anglophone reactions to the war than that usually presented in the histories of the era.

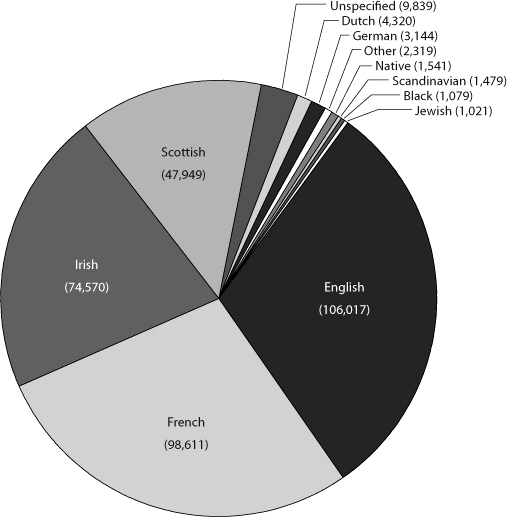

Figure 1: Ethnic Composition of New Brunswick’s Population, 1911. Mike Bechthold

In 1914, New Brunswick’s population was a unique mix of old and new and of the two founding peoples of the Dominion of Canada. According to the 1911 census, sixty-five percent of New Brunswick’s inhabitants were of British origin, including a very large Irish component, and twenty-eight percent were of French origin (see Figure 1). Though living in the same province, the two groups were divided by settlement patterns and geography. The French-speaking population was concentrated in the northern counties, along the coast of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Baie des Chaleurs and the upper reaches of the St. John River. English speakers mainly inhabited the south. Between the two lay the largely uninhabited forests of central New Brunswick.

In worship, the province held a slight Protestant majority, mainly Baptists, and was forty-one percent Roman Catholic. Intermarriage certainly occurred, but in religion, too, New Brunswickers tended to live apart, with the Protestants dominating the central and southern counties. Nearly half the Catholic population was of Irish or Scottish descent and by then had forsaken Gaelic for English. Most of these English-speaking Catholics lived among the Acadians, their co-religionists, across the northern and eastern edge of the province and in Saint John, where there was a strong Irish community. Indeed, the Irish, who came in their thousands in the mid-nineteenth century, were the last great wave of European settlers in the province.

New Brunswick also had much smaller populations of minority groups, including Mi’kmaq and Maliseet native peoples, confined to reserves generally located well outside the larger centres; some Danes (Canada’s oldest Danish settlement was New Denmark, in Victoria county), Germans and Dutch — people of Dutch extraction actually outnumbered Acadians in most of New Brunswick’s southern counties. Communities of Blacks, mainly descendants of Loyalists and freed slaves, could be found in Saint John, Fredericton and Kings and Queens counties, while small populations of eastern European Jews and Christian Lebanese, concentrated in Saint John — New Brunswick’s only true city in 1914 — further enriched the picture.

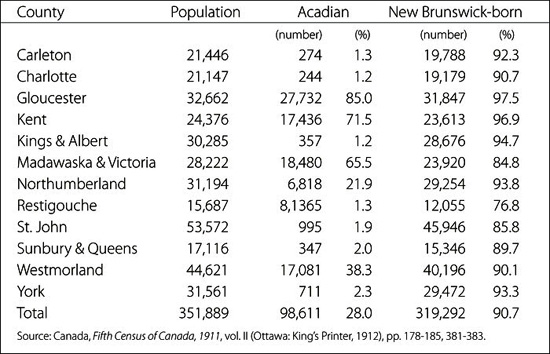

In summary, New Brunswick’s population in 1914 was seventy-two percent rural and, as Table 1 shows, ninety-one percent locally born. Most New Brunswickers were long settled in Canada and their employment or subsistence was based on the land or the sea; few retained immediate ties to the Old Country, and many opposed military service.

Table 1: New Brunswick’s Population by County, 1911

Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Liberal prime minister of Canada from 1896 to 1911 and the country’s elder statesman and opposition leader during the Great War. LAC C-001971

The act that started the Great War occurred on June 28, 1914, when a Serbian assassin struck down Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, in Sarajevo. One month later, following Serbia’s spurning of a series of harsh ultimatums, Austria-Hungary declared war on its tiny neighbour. This action triggered the complex set of alliances that divided Europe into armed camps. Russia, Serbia’s self-proclaimed protector, responded by declaring war on Austria-Hungary; Germany, allied with Austria-Hungary, declared war on Russia on August 1. Realizing the inevitability of a two-front war with Russia’s ally, France, the Germans violated the neutrality of Belgium to invade French territory. The German attack on Belgium then activated British guarantees for Belgian neutrality. Thus, on August 4, Great Britain declared war on Germany. The lines were drawn, with the Allied powers of Belgium, Britain, France, Serbia and Russia arrayed against the Central powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary.

Canada, a self-governing member of the British Empire, entered into this confusing European struggle under the doctrine of Unity of the Crown, which meant that Britain’s declaration of war automatically placed Canada at war, regardless of Canada’s separate government. It did not follow that Canada automatically had to become involved in the actual fighting, but public support demanded it. As the leader of the Liberal opposition, the esteemed Sir Wilfrid Laurier, stated, “When the call comes our answer goes at once, and it goes in the classical language of the British answer to the call of duty: ‘Ready, aye, ready’.” All the other self-governing British territories, including Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Newfoundland, joined Canada as key supporters of the British war effort.

Canada immediately accepted an obligation to provide soldiers for service overseas. In a country where the militia was a traditional feature of community life, it was only natural that Canadians would flock to the colours of their local army units. In time, this would evolve into more complex support for the war effort, including financial aid, the provision of food and the export of manufactured goods. But amid the enthusiasm to join the cause and the anxiety that it would all be over before Canadians shared in the adventure, few foresaw what the war would hold.

Soldiers remained Canada’s most important and most visible contribution, but this presented a problem when the war began. Despite popular enthusiasm and glowing promises of help, Canada’s military consisted of just 4,000 regular soldiers. If Canada was to field an army overseas, volunteers drawn directly from civilian life needed to be trained, equipped and transported to Europe. In 1914, finding enough recruits was not a problem. In fact, the First Canadian Contingent, composed of 30,000 eager if untrained and poorly equipped volunteers, sailed as soon as October 3. Most of these first men to go were recent British immigrants, who had flocked to Canada’s urban centres in the decades before the war (though only eleven percent of the total Canadian population, they accounted for sixty-four percent of the First Contingent). A sense of adventure, perhaps a desire to return to Britain or, for native-borne Canadians, to see Europe and play a role in the victory motivated these early volunteers, but most also felt a strong personal attachment to Great Britain.

When the conflict began, Canadians confidently expected victory, and soon. This assurance was based on little other than the British, and limited Canadian, fighting in the Boer War of 1899 to 1902, hardly the British Empire’s finest military accomplishment. This experience had nothing in common with the First World War, however, which became — even in its opening weeks — a major conflict involving all of the heavily armed Great Powers of Europe. Thus, at first, Canadians made appeals to the British Empire or even to their Loyalist past and expected patriotic volunteers to lead a quick and glorious triumph over the nefarious German kaiser. But, over the next two years, as the war settled into a grim stalemate and the casualties mounted, Canadians’ outlook on the great adventure changed, as did the nature of their contribution to the war effort. The New Brunswick experience particularly illustrates these shifts.

When the war began, New Brunswick supported Britain and the Allies with the same enthusiasm as the rest of Canada. The provincial Historical Society even proposed changing the name of the province to Acadia, given “the tainted Germanic origins of Brunswick.” In the same patriotic mindset, the provincial government swiftly authorized a gift of 40,000 barrels of New Brunswick’s finest potatoes for Britain and the suffering people of Belgium. Members of the provincial Legislative Assembly (MLAs) F.B. Black and Percy Guthrie immediately enlisted, while prominent Saint John politician L.P.D. Tilley became the provincial recruiting officer. Westmorland county raised the 8th (Moncton) Battery for service overseas with the Canadian Field Artillery. The French-speaking Acadian population openly supported the war effort as well. Gloucester Member of Parliament Onésiphore Turgeon noted in his memoirs how all of Bathurst was talking of the war and that his constituency office was besieged with people eager to find out as much as possible about the European crisis.

Despite public enthusiasm for the general cause, however, few immediately answered the recruiter’s call, and fewer than a thousand New Brunswickers could be found in the ranks of the First Canadian Contingent. In part, this was because the contingent contained no designated New Brunswick battalion, despite the best efforts of local politicians and militia officers. But the principal reason for the initial poor response was the long-settled nature of New Brunswick’s population. Just 1,100 of the 400,000 immigrants who had come to Canada in the year before the war began had made their homes in New Brunswick, while thousands of young, single New Brunswick men — ideal potential recruits –– had left the province over the decade before the war in search of work in the burgeoning industries of the northeastern United States and central Canada. Many of these young New Brunswickers may have enlisted where they lived elsewhere in Canada, but others went about their business making a living in the mill towns of Massachusetts.

Despite these hindrances, New Brunswick raised a substantial force for overseas service in the early stages of the war. The artillery units possessed a long tradition, and occupational experience led many to join support units, but infantry battalions of a thousand men each represented the primary form of group participation in the war. According to prewar plans, these were supposed to be raised by local militia units. But the minister of militia and defence, Sir Sam Hughes, a brash, opinionated and self-important Ontario Orangeman, threw out the plan. Instead, battalions were raised in an ad hoc fashion, through local initiative and often under the aegis of wealthy businessmen and friends of Hughes or the Conservative party. It was a chaotic and alarmingly inefficient system, and of the 258 infantry battalions raised, only some fifty eventually served at the front; the rest were broken up for reinforcements.

New Brunswick attempted to raise nine infantry battalions during the war. Of these, only the 26th Battalion saw service on the Western Front. The others, the 55th, the 104th, the 115th, the 132nd, the 140th, the 145th, the 165th and the kilted “Highland” 236th were sent overseas, then dispersed as reinforcements. This trend began early on, when drafts of volunteers from New Brunswick sent to join the First Contingent assembling at Valcartier, Quebec, were concentrated in the 12th Battalion, which then provided reserves for the other infantry formations. Despite the disappointment the faulty recruiting system caused, eager volunteers rapidly filled the ranks of a Second Canadian Contingent, which in 1915 fostered Canada’s image as an inexhaustible supply of troops — an image soon disputed by events.

New Brunswick’s “Fighting 26th” Battalion leaves Saint John for overseas service, June 13, 1915. NBM 1988.67.17

By the time the 1st Canadian Division reached the battlefields of Europe in early 1915, the war had devolved into a stalemate. The initial German offensives had been halted, but not before the enemy had captured large portions of northern France and all but a small sliver of western Belgium. Neither side could achieve the desired breakthrough, which had forced the building and consolidation of trench systems stretching from the English Channel to the Swiss frontier. As a Canadian captain, Maurice Pope, noted, “It strikes me as being a test of endurance and nothing else, for I do not see how Fritz can move us, nor how we can dislodge him.” The 1st Canadian Division first saw action in March at Neuve Chapelle in northern France, but the real baptism of fire came during the struggle called Second Ypres.

The major city in the Flanders region of western Belgium, Ypres was a transportation hub for road, rail and canal traffic. It was there, during the First Battle of Ypres in November 1914, that the British stopped the final German push to the sea before the front stalemated. By early 1915, the British Expeditionary Force, of which the Canadians were a part, still held a broad, deep bulge into the German lines east of Ypres. Second Ypres, fought by Canadians from April 22 to May 25, 1915, witnessed the first large-scale use of gas as a weapon in warfare. The Allies did not want to relinquish Ypres despite its vulnerable position, especially since the cause of Belgian freedom remained one of the most important factors underpinning British support for the war. The Canadians, who had seen only limited fighting to that point, found themselves in the thick of intense combat after French North African troops fled from the chlorine gas the Germans released on the first night of the attack. Two days later, the Germans used gas again in an attempt to break through the new Canadian lines. Without gas masks or the other protective measures that would be developed later in the war, the soldiers improvised, urinating on their uniforms and covering their noses and mouths for protection. The German offensive made gains, but the Allies, thanks in large part to the determined stand made by Canada’s raw volunteers, managed to prevent Ypres itself from being captured.

Second Ypres produced the first long casualty lists in papers back home, as more than 6,000 Canadians were killed, wounded or captured in the confused fighting. The April 26, 1915, the Moncton Transcript trumpeted, “Canada Mourns Her Honoured Dead Who Fell That We May Live!” while a smaller headline declared, “Complete [Casualty] Lists Have Not Yet Been Received, But List Already to Hand Is Large.” That list proved to be just the beginning.

All the while, New Brunswick recruiters laboured to keep pace with these losses and the simultaneous massive expansion of the military as new divisions were formed for active service. In line with national trends, for the first two years of the war, recruiting in New Brunswick was conducted primarily by anglophone recruiters based in the larger centres, while volunteers came forward on their own initiative from the rural and northern parts of the province. The inclusion of the 26th New Brunswick Battalion — raised easily in 1914 and 1915 — in the Second Canadian Contingent suggested that New Brunswick’s contribution to the war would be as glorious as that of any other part of the Empire. The nominal roll of the Fighting 26th’s original members reveals a formation drawn mainly from Saint John but with significant minorities of recruits from throughout the Maritimes, the Gaspé and Maine. When the 26th sailed overseas from Saint John on June 13, 1915, Hope A. Thomson of 319 Princess Street penned a special poem, “The 26th Battalion,” in honour of the event. Certainly, this kind of public support suggested that many more recruits could be found.

In addition to the infantry battalions, New Brunswick provided other formed units for the Canadian Expeditionary Force such as the 2nd Division Ammunition Column, on parade in downtown Fredericton, spring 1915. (see the balance of this image on pages 30-31). Courtesy of Donald E. Kelly

In fact, the 26th Battalion took most of those who then wanted to go, and there was no system within the Canadian army to ensure that future volunteers from New Brunswick would find their way to the 26th. The transport ships had barely departed before Saint John’s mayor, James Frink, publicly questioned his own constituents’ willingness to serve. On June 29, the mayor challenged a crowd in King’s Square, asking rhetorically, “Must we say, hereafter, with bated breath that this is the city of the Loyalists? Must we say at this momentous period, fraught with the gravest responsibilities ever cast upon British people, that there exists within the border of this province at least 5,000 men, physically fit, and from whom a bare 800 have displayed sufficient courage and patriotism to unsheath the sword in defence of their homes?” Daniel MacMillan, a fifty-two-year old York county subsistence farmer, kept a similar record of recruiting talks in his diary, noting in the summer of 1915: “I am just home from the recruiting meeting, quite a large attendance of women and old men, but not very many of those who are fit for fighting age. Major Day talked very plainly and also very forceable. Said a few things in a sort of peculiar way, did not just say we were cowards, but that was the inference which some of his remarks seem to imply.”

Mayor Frink and Mr. MacMillan understood the situation correctly, for after the raising of the 26th Battalion, volunteers continued to come in large numbers only from specific areas. Men from Carleton county’s so-called Baptist Bible Belt were eager to join. Likewise, the Westmorland shiretown of Dorchester enlisted nearly every eligible male in the 145th Battalion, necessitating the creation of a separate Dorchester platoon, with its memorable motto “For King and Country and to Help Paint Dorchester on the Kaiser’s Front Door.” The province’s tiny universities also backed the war to the fullest, with Sackville’s Mount Allison University enlisting seventy percent of its male student bodies in 1915 and 1916 and the Loyalist-founded University of New Brunswick making military drill compulsory for male students from the 1915 academic year.

“The 26th Battalion”

I

From fair New Brunswick’s fruitful Land,

And our city by the sea,

We go to lend a helping hand

In the cause of liberty

O’er bloody fields the cannons roar,

In fancy we see the fray;

The transports gather near our shore

And we long to be away.

We are not afraid

Of the German blade,

Nor the shriek of the German gun.

Then Oh! to advance

With the ranks of France,

In the wake of the murd’ring Hun.

II

From wronged and ravished Belgium

We have heard your anguished cry.

Oh! brothers, brothers, sure we come

To balance the bill, or die.

Soon may our slogan proudly ring.

‘Mid the lead hail’s rattle-On!

For love and home, for God and King,

And the fame of fair Saint John

We are not afraid

Of the German blade,

Nor the shriek of the German gun.

Then Oh! to advance

With the ranks of France,

In the wake of the hell hound Hun.

Source: R.W. Gould and S.K. Smith, The Glorious Story of the Fighting 26th, New Brunswick’s One Infantry Unit in the Greatest War of all the Ages (Saint John, NB: S.K. Smith, 1920), p. 17.

Of course, among those individuals who did enlist, motivations varied. Like John Lavigne of Bathurst, some New Brunswickers had a military past. Lavigne had lost an eye serving in the Boer War, but he refused to let that prevent him from signing up a second time. Upon being rejected by a medical board in Saint John, Lavigne asserted, “I’m as good as any Frenchmen as ever lived in Bathurst, and I’m going to make a few sit up and take notice, even though I have only one good eye.” Sure enough, he was at the front with the artillery a few months later.

Just three months after the war began, Percy Till of Saint John left behind his promising job as an assistant wire chief with the New Brunswick Telephone Company to enlist with the 26th Battalion. The twenty-year-old served with distinction overseas, quickly rising to the rank of sergeant. Stephen Pike of Grafton, who also served overseas with the 26th Battalion, represents a more typical recruiting example. Private Pike went on to take part in some of the worst fighting of the war, including Vimy Ridge, Passchendaele and the Hundred Days, but the ideals of the British Empire had not really been his motivation when he enlisted at age eighteen. “We just kind of got shamed one another into joinin’ up,” remembered Pike, “It wasn’t that I was patriotic or anything like that. I was just a kid and didn’t know anything. The rest of the boys around that I went to school with were joinin’ up so I, they talked me into it. Which wasn’t a very hard thing to do. I kind of got worked into it by degrees.”

Enlistment was particularly important for one group, the Lebanese of Saint John. Since Lebanon was occupied by the Ottoman Empire and the Turks had thrown in their lot with the Germans, some members of the small community became “enemy aliens.” The local Syrian Protective Agency — “Syrian” actually being Lebanese — protested against this move, for, as the November 4, 1914, Saint John Evening Times and Star noted, “it is not correct to classify them among the alien enemies of Great Britain . . . nothing would give greater pleasure to the Syrian Christians than the destruction of Turkish power.” The community raised large sums for the Patriotic Fund, and sent its young men to fight overseas. On March 19, 1915, the St. John Standard proudly reported the enlistment of John Beshara in the 25th (Nova Scotia Rifles) Battalion. Beshara told the cheering crowd at his send-off that “he could not speak good English, but could say that although a foreigner he had been used very well in St. John, and that he was pleased to take the oath to fight for King George.”

145th (Kent-Westmorland) Battalion parading on Main Street, at the foot of Allison Avenue, Sackville, June 1916, just prior to leaving for Valcartier. Mount Allison University Archives 8317/10/1

The memories of other New Brunswickers illustrate still different enlistment motivations, while simultaneously emphasizing the difficulties of finding more recruits. For example, Private Vincent E. Goodwin from Baie Verte, near Port Elgin, joined the 145th Battalion from Kent-Westmorland, which was unable to fill its ranks despite Dorchester’s support. In the end, the 524 members of Private Goodwin’s 145th Battalion proceeded overseas, where they were broken up to serve as general reinforcements for units already in France. A similar fate befell all other attempts to raise battalions after the 26th. In the case of the 145th, there were just not enough young people available in southeastern New Brunswick, for Goodwin also recalled that many of his neighbours wished to serve but were simply too old for the infantry or artillery. Older recruits joined the noncombatant Railway Corps, like Saint Johner Walter Brindle, who enlisted at age forty-five, in part to stay close to his three sons, all of whom had joined the infantry. Other options included the forestry units and the dangerous job of transporting supplies to the front line by horse, which James Robert Johnston from Notre Dame (just outside Moncton) experienced with the Canadian Machine Gun Corps. All of these units were vital to the war effort, and long Canadian experience with agriculture, logging and railway construction meant that the country became an extremely important source of these valuable recruits.

A few New Brunswickers joined the navy, and an even smaller number became flyers. Provincial newspapers regularly printed naval recruiting appeals in both English and French, and that service coveted the province’s many fishermen. Vincent Goodwin’s brother, E. Leslie Goodwin, answered those appeals and served as a petty officer aboard minesweepers during the war. A select few also served in the various air arms of the British forces. Alfred-Hillaire Belliveau, a member of one of Fredericton’s most prominent families, first enlisted in the infantry, but, after growing bored with the trenches, transferred to the more exotic service in the skies. Point de Bute’s own Major Albert Desbrisay Carter became one of the Royal Flying Corps’ top aces of the war, shooting down twenty-nine German aircraft and receiving the Distinguished Service Order and Bar.

As the war worsened, so did the recruiting problems. In part, this was because of the enormous casualties and apparently futile battles of trench warfare. This waste was brought home to Canadians by the great Allied attempt to dislodge the Germans in 1916 during the Somme campaign. Lasting from July 1 until late November, the offensive resulted in minimal gains in territory and utterly horrendous losses. The Somme attack aimed to relieve pressure on the French forces besieged by the Germans around Verdun, as well as to advance the Allied lines over an extended front. The battle is best remembered for its disastrous first day, when nearly 20,000 British Empire soldiers were killed and 40,000 wounded. Canadians on the Western Front, now swollen to four divisions each made up of 20,000 soldiers, missed the early months of the Somme, but their turn came in September. For the 26th Battalion, the Somme proved to be their first extended action: as part of an effort by three Canadian divisions, they played a notable role in the mud-soaked and bloody capture of what little remained of the village of Courcelette. It cost them 225 dead, and by the time the Somme fighting was over, virtually all of the surviving members of the 26th Battalion had been wounded. The fighting for that village and its fortified sugar-beet-processing factory was so fierce that Lieutenant Colonel T.L. Tremblay, commanding the 22nd (French Canadian) Battalion alongside the New Brunswickers, exclaimed, “If hell is as bad as what I have seen at Courcelette, I would not wish my own worst enemy to go there.” The 26th also suffered heavily in the fruitless late September and early October attacks against Regina Trench, which lay behind a long, low ridge beyond Courcelette. By early October, the 26th Battalion’s 5th Brigade had taken so many casualties that it had to be withdrawn from the front-line trenches for lack of able-bodied troops. Overall, more than 600,000 British Empire soldiers, including 24,000 Canadians, were killed, wounded or went missing during the Somme offensive.

No. 4 Overseas Siege Battery, on parade, Saint John, probably just prior to leaving for Britain in April 1916. The unit arrived in France in July 1917 and saw active service until the end of the war. NBM 213974

The bloodletting of the Somme led to the first calls in Canada to raise soldiers through compulsory military service. Conscription had a long history in Europe, and even Canada retained residual powers — not used since the colonial era — to call all able-bodied men to the colours. But since 1868 Canada had officially relied on a combination of a small professional cadre and voluntarism among its militia forces to field armies. In 1914, this was the model used throughout the British Empire. By 1916, however, Britain had adopted conscription, not least because it allowed the government to manage labour more effectively and to keep skilled munitions workers in their factories.

By the same year, Canada faced similar problems: heavy casualties at the front and the need to administer labour at home. Moreover, once Canada was committed to the fight, many did not want the country to back down. Prime Minister Borden emphasized this resolve with his January 1916 promise that the Canadian Expeditionary Force, the name given to all of the Canadian troops overseas, would expand from 150,000 to 500,000 soldiers. This number required a major commitment of resources for a country of just eight million people, which also had a booming wartime economy. With four infantry divisions fighting in France, a fifth division training in England and voluntary enlistment on the decline, it was unclear in early 1916 just how Borden’s ambitious commitment could be met.

The desire to continue the country’s tremendous support for the war effort in the face of the losses suffered in Europe made reinforcing the troops in action the main issue at home. In the rush to get soldiers overseas as quickly as possible, however, little attention had been paid to who was joining up. Once volunteers became more difficult to find, the question of who was enlisting and who was not overshadowed even the fighting. While some groups — notably certain labour unions, socialists and pacifists — opposed the war outright, these were small organizations spread throughout the country. More importantly, the events of 1916 revealed a growing rift between French and English Canada that could not be ignored. French Canadians, especially in Quebec where they formed the majority, were not volunteering in numbers anywhere close to English Canadians. While there had been public declarations of support for the war throughout Quebec in the early patriotic period, these had stopped as the war dragged on into 1915. By the Somme battle, only one battalion of French Canadian troops, the 22nd, was overseas, and the handful of other French-speaking units in existence could not find enough volunteers.

There were many reasons for this difference in the recruiting response of English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians. For one, French Canadians did not look to either France or Britain as “mother” countries and they could see no compelling Canadian reason to fight in Europe. France had abandoned French Canada in the eighteenth century and the French Revolution broke with Catholicism shortly thereafter. French Canada had thus developed without any assistance from France, while remaining staunchly ultramontane Catholic. Some parish priests even instructed their flocks that the German invasion represented divine punishment for France’s having abandoned religion. Catholicism also stressed large families, which meant marrying young, whereas single men were much more likely to enlist. While French Canadians certainly did not feel the need to enlist in aid of France, and concern for family, religion and culture took precedence over all else, the lack of connection with Britain — and with the rest of Canada — was exacerbated by the actions of English Canadians.

Indeed, the background to the social division of the First World War may be seen in three events: the Boer War, the debate over the creation of a Canadian navy and legislation that eliminated French-language schooling in many parts of the country. The Boer War best illustrated the precedent of internal division in wartime. Many French Canadians sympathized with the Boers, an ethnic and linguistic minority of strong religious convictions fighting bravely against the mighty British Empire. To avoid splitting the country, the then-prime minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, decreed that only volunteers would be sent to fight in South Africa. This allowed British Canadians to support the war — and they provided the vast majority of the more than 7,000 Canadian volunteers — while French Canadians could choose to avoid fighting. For its part, New Brunswick enthusiastically supported the British war effort against the Boers, producing so many volunteers that recruits had to leave the province to find space in units that had not already reached their quotas. Laurier, himself a prominent French Canadian, always recognized the danger of avoiding compromises of this sort. As he said in a speech to the House of Commons in May 1900, “If we had refused our imperative duty the most dangerous agitation would have arisen, an agitation which, according to all human probability, would have ended in a cleavage in the population of this country upon racial lines. A greater calamity could never take place in Canada.”

The Naval Bill, 1910 legislation proposing the creation of a Canadian Navy, unleashed another controversy that threatened the “great calamity.” A navy would be certain to operate outside the narrow confines of Canada’s three-mile territorial limit, by necessity under the control of the Royal Navy, the largest in the world but increasingly threatened by the growth of the German forces. The German threat had prompted the Canadian effort to create a national service to help the British. While the bill was being debated in the House of Commons, Henri Bourassa, publisher of the influential Montreal newspaper Le Devoir, attacked the measure, which he claimed was “non pas pour defendre le pays natal, mais pour se battre sur toutes les terres et toutes les mers du monde en faveur du drapeau anglais.” It should not be assumed that French Canadians were pacifists, for they did fight for causes of their own — for instance, five hundred French Canadian volunteers served with the Papal zoauves, a force raised by the Catholic Church to defend Papal territory during the Italian wars of the 1860s, and the 1870 and 1885 rebellions against the Canadian government in the west were led and supported by francophones. The navy was created nonetheless, but, as Bourassa understood, Quebecers opposed fighting and dying for what they saw as British imperial causes.

Provincial laws on language education, however, contributed most to friction between French and English Canadians. In June 1912, the Ontario government passed Regulation 17, which made English the sole language of instruction in that province’s schools. The French-speaking community of 250,000 people, ten percent of Ontario’s population, resented this measure, which they later compared unfavourably to German actions. French Canadians in Quebec looked on hopelessly, fearing for their own language rights, which now seemed more threatened than ever. Similar wartime legislation in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, which stripped away French schooling, clearly told French speakers that they had become second-class citizens in their own country. This certainly did not help French-speaking recruitment for the military.

Finally, recruiting problems were fostered, bizarrely, by the minister of militia and defence himself, the colourful Sir Sam Hughes. Hughes had fought in South Africa, where he had been dismissed for indiscipline and where, by his own reckoning, he had deserved to win two Victoria Crosses. He was certainly brave, as he regularly demonstrated in the field. On one occasion during the fighting on the veldt, he simply rode into a large Boer encampment, advised the Boers they were surrounded and demanded their surrender, which he promptly received. The Boers quickly realized the ruse, however, and melted away to avoid capture by the British forces that were actually about to surround them. Hughes’s impetuousness infuriated the British officers; nonplussed, he demanded a Victoria Cross for his efforts. His disdain for regular soldiers and belief in the unbeatable power of the volunteer colonial carried over into his tenure as minister of militia. Hughes abandoned the mobilization plan, which was based on existing militia battalions and carefully prepared before the war by the Canadian General Staff, and replaced it with a system of recruiting based on popular enthusiasm using local social and political connections. If you knew the minister and had money, he could make you an officer, let you raise your own unit and choose your own subordinates despite your total lack of military experience. Moreover, the devout Orangeman Hughes prized Protestant recruits, favoured kilted “Scottish” and “Irish” battalions, opposed non-English-speaking units — which provided yet another reason for francophones not to enlist — and paid little heed to the distinct needs of industry or agriculture. By any measure, Hughes’s recruiting system was a disaster, and it fostered friction between urban and rural, French and English, and Catholic and Protestant Canadians.

By mid-1916, as a result of Hughes’s bungling, more than two hundred battalions struggled to fill their ranks with a thousand men each for overseas service. Yet, fewer than fifty infantry battalions saw active service with the Canadian Corps at the front, and after July 1916 no battalion reached full strength through voluntary enlistment. The high costs of recruiting and ruinous competition between units, coupled with the high casualty rates, made conscription an attractive alternative by the end of 1916.

Recruiting had been difficult in New Brunswick almost from the beginning, so those in charge tried to adapt to the situation and somehow find volunteers. While official enlistment campaigns remained focused on anglophones living in larger centres, these held only a small portion of the province’s population. As a result, by 1916, recruiters began canvassing in isolated fishing villages, family farms, lumber camps and among the French-speaking population. These belated actions proved to be too little too late and actually alienated supporters in rural areas and among minority groups.

Recruiters remained opposed to making use of one segment of New Brunswick’s population eager to fight: Blacks. In 1915, twenty Black recruits were sworn in at Saint John, but when they arrived in Sussex to join the 55th Battalion, they were told that they were not wanted and were sent home. A member of the group, Percy T. Richards, recalled what happened next: “We would go to the recruiting centre in Sussex. I went there with some friends several times. The recruitment officer, who was of German descent, told us that it was not a Black man’s war.” In response to this situation, Saint John MP William Pugsley sought a clarification of the government’s policy in the House of Commons. On March 24, 1916, Pugsley noted: “There is a good deal of complaint and a very considerable amount of feeling among our coloured citizens that they have not been treated fairly. They have been told that their services would be accepted, and when they have gone to the recruiting office where they were told to go, they have been sent away without satisfaction.” Sam Hughes replied that Blacks could enlist, but they had to be accepted by a battalion’s commanding officer, though no other recruits required such scrutiny. Commonly held prejudices meant that very few Blacks were accepted in this way, and most had to wait until the formation of the segregated and noncombatant No. 2 Construction Battalion in 1916 to serve. Of the six hundred recruits who initially went overseas with that battalion (largely recruited from Nova Scotia), thirty-three came from New Brunswick, including twenty-six from Saint John.

William Pugsley, former Liberal premier of New Brunswick and federal minister of public works under Sir Wilfrid Laurier. He was appointed lieutenant-governor in November 1917. PANB P106/37/50

Though reluctant to enlist Blacks, the recruiting authorities welcomed the support of other minority groups. The province’s Catholics of Irish descent volunteered in large numbers, despite some initial lack of enthusiasm for the war. New Brunswick was not spared the ethnic tensions that marred Ireland itself, with many Orange and Republican supporters active in the province. In fact, a native New Brunswicker, Andrew Bonar Law of Rexton, Kent county, was not only the leader of the British Conservative party, but also a fierce opponent of Irish Home Rule reputed to have smuggled weapons to Ulster Protestants. For their part, many Catholic New Brunswickers of Irish descent sympathized with Republicanism, although there was no open support for the Dublin Easter Rising of April 1916, which was crushed by British forces following bloody street battles. New Brunswick’s small Jewish population, concentrated in Saint John, also supported the war; some even volunteered to join the British forces fighting in the Middle East. Americans who came north to enlist before the United States entered the conflict in April 1917, particularly men from Maine and Massachusetts, also provided an important source of volunteers recruited in New Brunswick.

Band of the No. 2 Construction Battalion, composed largely of men from Saint John: (front row, from left to right) Herbert Nichols, George Richard Dixon, Bandmaster Sergeant George William Stewart, Seymour Tyler, Harold Bushfan; (rear row, from left to right) Albert Carty, Fred Charles Dixon, Percy William Thomas, James Albert Sadlier. Courtesy of Heritage Resources

Sir Pierre-Amand Landry, the first Acadian provincial cabinet minister, the first Acadian appointed to the New Brunswick Supreme Court, the only Acadian to be knighted and a strong supporter of Canada’s war effort. Two of his sons served overseas. CEA PB1-190

The largest minority group in the province, the Acadians, began to receive special attention from recruiters in 1915 and 1916. Historians have tended, erroneously, to lump the wartime attitudes and experiences of this large group, more than a quarter of New Brunswick’s population at the time, with those of the French Canadians of Quebec. In fact, Acadians did not oppose the war, at least no more so than did other rural peoples. Rather, the recruiting system simply failed to address them directly in their own language and their own areas. English remained the sole language of the recruiters and of New Brunswick’s military units, and recruiting camps remained concentrated in English-speaking areas. In response to these difficulties, Acadians publicly stressed their support for the war effort, emphasizing that their voluntary service represented their distinct collective patriotism. Sir Pierre-Amand Landry, a Provincial Supreme Court justice and community leader, spoke throughout the province in favour of the Allied cause. On November 25, 1914, for example, Landry made this appeal to a packed crowd in Shediac: “Deux de mes fils prennent les moyens de se rendre sur la champ de battaile et je verrais avec satisfaction, quelque triste qu’en soit la nécessité, l’enrôlement volontaire d’un membre de chaque famille du Nouveau-Brunswick . . . montrer autant de patriotisme et d’héroïsme dans une crise qui menace la base même de la civilisation chrétienne.”

Louis-Cyriaque D’Aigle, the Moncton dairy industrialist who sought to demonstrate Acadian support for the war and find a way to distinguish the Acadian community in the process by forming a uniquely Acadian infantry unit, the 165th Battalion. Note the Stella Maris of Acadia in the cap badge. CEA, from Un aperçu historique, et un régistre photographique de bataillon “acadien” d’outremar 165ième F.E.C., Book BG 19

Acadians enlisted anyway, and in late 1915 they even founded their own unit, the 165th (French Acadian) Battalion, based in Moncton and commanded by prominent dairy producer Louis-Cyriaque D’Aigle. Inspired by the belief that English-speaking formations both disguised Acadian support for the war and threatened Acadian identity, the 165th Battalion was established to demonstrate loyalty to the Empire and help enshrine Acadian rights. From the beginning, Acadian leaders stressed the distinctiveness of their people, and one of Lieutenant-Colonel D’Aigle’s first recruiting cries, aimed more at his anglophone military superiors than anyone else, asserted that “the French Acadians are a distinct people from the French Canadians both in character and temperament.” Monsignor Jean Vital Gaudet became the unit padre, bringing the blessing of the Catholic Church with him, and Major Joseph Arthur Léger was recalled from active duty with the 26th Battalion to serve as the second in command. Unfortunately for D’Aigle and his supporters, the battalion, although the only unit authorized to recruit throughout the Maritimes, sailed for Britain on March 28, 1916, with only twenty-four officers and 526 men — two hundred short of its required establishment. It was disbanded in September 1916 to provide reinforcements for the front and men for the Canadian Army Forestry Corps.

Some of the officers of the 165th Battalion. Major Joseph Arthur Léger went on to command the North Shore Regiment in the opening days of the Second World War. CEA, from Un aperçu historique, et un régistre photographique de bataillon “acadien” d’outremar 165ième F.E.C., Book BG 19

Whether the 165th could have been supported in combat by reinforcements from the Acadian community will never be known, but the loss of this symbol made other Acadians less likely to enlist — and those who did were likely to end up in the 22nd (French Canadian) Battalion. Nonetheless, many went overseas with the 132nd (North Shore) Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel G.W. Mersereau, or with the 145th Battalion, which had recruited heavily in the north; both of these battalions were broken up as well. Since the enlistment papers asked no questions about ethnicity or mother tongue, however, it was very difficult at the time to determine how many Acadians had joined up. Most English New Brunswickers believed very few had and did not hesitate to say so publicly. As the conflict plodded on, the province’s mainly English-speaking political elites accused Acadians of not supporting the war effort and publicly labelled them as slackers, the most negative contemporary insult available.

Despite the support of many New Brunswickers throughout the province, then, recruiting remained a difficult task. As a result, still more reforms attempted to encourage enlistment. The most noticeable of these appealed not to patriotism but to the supposedly lesser concern of earning a living. For instance, in 1916, the town of Moncton, following the lead of many other Canadian communities, made previous military service a requirement for municipal employment. In doing so, the municipality echoed the Conservative-controlled provincial legislature, which had passed a pro-conscription resolution on April 12, 1916, two months before the Somme campaign even began.

In keeping with the growing sense of desperation over support for the military effort, the most ambitious provincial recruiting drive began in September 1916, as the Canadian Corps moved onto the blood-soaked fields around Courcelette. That April, recruiting authorities had already established special committees to address the public, which aimed “to turn every public gathering, for a few minutes at least, into a recruiting rally so that wherever men and women gather they will be met with the call of duty.” In retrospect, the September effort that made such an impression on Woodstock represented the last major appeal for volunteers in New Brunswick. Spearheaded by Lieutenant-Colonel Percy Guthrie, the MLA for York and wounded veteran of Festubert, the campaign held more than two hundred public rallies to stimulate enlistment. On the colonel’s insistence, New Brunswick also used the electoral rolls to target men available for service.

Despite these efforts, voluntary recruiting had largely finished and the campaign produced meagre results: at one rally, one of Guthrie’s largest, thousands crowded King’s Square in Saint John, but only four men stepped forward to enlist. The lack of new recruits had an especially adverse effect on the 26th Battalion, New Brunswick’s most visible contribution to the war effort. The 26th had been involved in every major Canadian action since its baptism of fire on October 13, 1915, ensuring a need for constant reinforcement. Both politicians at home and the troops in the trenches wanted those reinforcements to come from the province. Increasingly, as Figure 2 illustrates, they did not.

New Brunswick enrolled nearly 9,000 recruits from September 1915 to December 1916, but few went to the 26th Battalion or even into the infantry at all. A provincial recruiting officer wrote to Ottawa, “I find the same conditions in this district as prevails in the other parts of Canada, if the reports which are received are true, namely, that recruiting is at a low ebb, and especially recruiting for the infantry. All who want to go have gone, and everyone who enlists now does so as a result of pressure.”

New Brunswickers of every origin clearly supported the war, but by 1916 strong economic factors were working to keep men at home. In each year of the war, the provincial economy had grown, employment had risen steadily, potato and timber prices had increased, and the province itself had remained free from direct threats. The fishing industry had become a prime beneficiary of large shipments of food overseas, and government slogans such as “Eat fish as patriotic duty” and “Buy Fresh Fish, Save the Meat for our Soldiers and Allies” were commonplace. The troops were provided large amounts of alcohol, which meant more jobs at the Moosehead and Red Ball breweries in Saint John, over prohibitionists’ loud protests. Foundries, mines, timber operations and newly established munitions plants needed skilled employees as they expanded. Even wooden shipbuilding was partly revived. Daniel MacMillan, a farmer from Williamsburg, near Stanley, best characterized these pragmatic sentiments, recording in his diary, “I really think I can do my bit better here on the farm than any other place.” This new-found economic improvement had an especially strong effect on Acadian areas, which tended to be even poorer than southern New Brunswick. For instance, the 165th (French Acadian) Battalion had been broken up to provide more troops for the Forestry Corps. For Acadians, the lesson was simple: why join the army and cut trees when you could stay at home and do it for much better wages?

Small inshore fishing schooners set off from Caraquet, a dangerous and labour-intensive — but essential — part of the province’s war economy. PANB P4/5/15

Perhaps most important of all, New Brunswick had no contingency plans to care for the dependants, widows and orphans of troops, or for the wounded returned soldiers themselves. This form of welfare fell to provinces and local charities, and then — as now — New Brunswick was a poor province. Assistance from Ottawa, additional taxation and public subscriptions helped, but such a glaring and often visible lack of help did recruiting no good, particularly in contrast to the support wealthier provinces provided. As a result, by the end of 1916, most of those New Brunswickers who had not already enlisted had chosen to remain on the ancestral land of their farms or in their fishing villages, making a better living, staying close to their families and not risking life and limb in a distant and seemingly never-ending conflict.

New Brunswick, like the rest of Canada, had reacted enthusiastically to the outbreak of the Great War, although the predominantly locally born population was not well represented in the First Contingent. For the Second Contingent, recruiting numbers compared more favourably with those for the rest of the country, and New Brunswickers displayed evident public pride in the Canadian sacrifices at Second Ypres and the Somme. By 1916, however, the deepening crisis of the war, the lack of new recruits and a perceived failure of Acadians to do their part, began to play on the prejudices and fears of many anglophone New Brunswickers. In light of the general situation at the end of that terrible year, the Canadian people faced desperate choices: would the government maintain voluntary enlistment in the hope that reinforcements could somehow be found and a national crisis averted or would it risk a crisis to raise the troops needed to win the war? What would the decision mean for New Brunswick?