Figure 2.1: Five Intrapreneurial Characteristics: The 5 Ps

Intrapreneurship borrows from the principles of entrepreneurship. Whereas entrepreneurship is the act of spearheading a new business or venture, in-trapreneurship is the act of spearheading new programs, products, services, innovations, and policies within your organization.

—Douglas S. Brown, Malcolm Baldrige School of Business, Post University1

Like entrepreneurs, intrapreneurs have always existed in varying forms, but it was not until 1978 that American entrepreneur Gifford Pinchot introduced the term intrapreneurship in a paper he authored with his wife, Elizabeth. Intrapreneur, a contraction of the term intra-corporate entrepreneur, describes an individual within an organization who is an innovator and change agent.2

Entrepreneur Steve Jobs used the term in a 1985 Newsweek article published after his resignation from Apple Computer. Jobs said, "The Macintosh team was what is commonly known as intrapreneurship . . . a group of people going, in essence, back to the garage, but in a large company."3

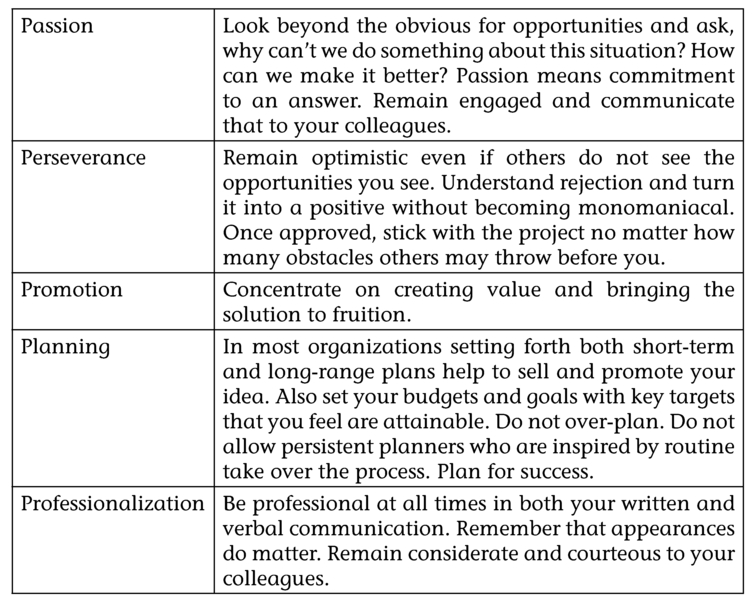

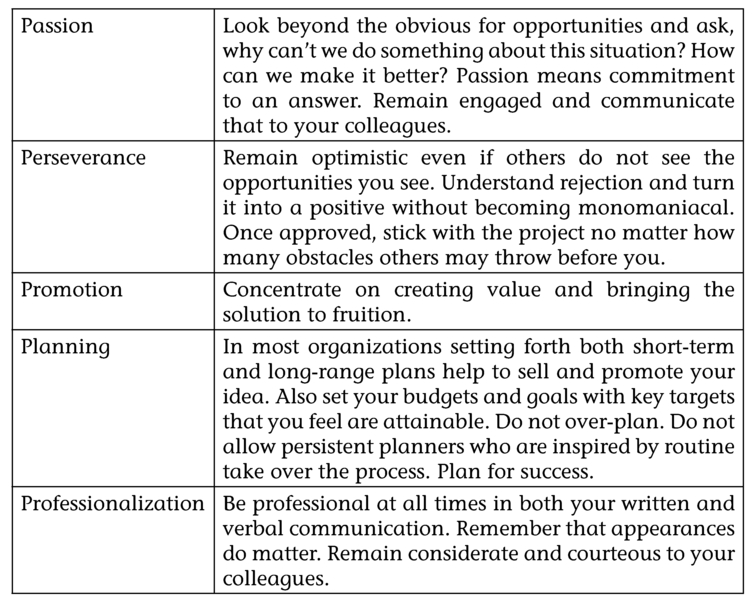

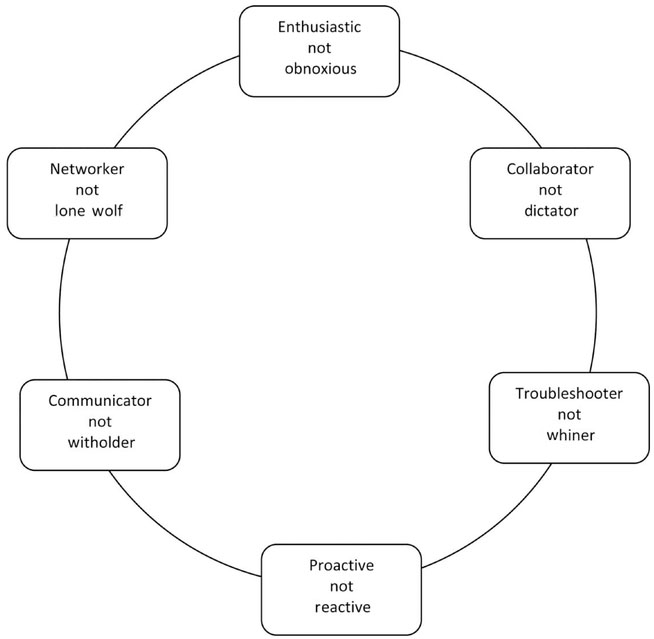

As the term made its way into the standard management culture in the 1980s, many organizations, non-profit and for-profit, embraced the concept, that is, the concept of creating effective change through passion, perseverance, promotion, planning, and professionalization within an organization. These became key words to describe the internal change agent, the innovator, the intrapreneur. These 5 Ps as highlighted in Figure 2.1 epitomize the intrapreneurial mind set.

Figure 2.1: Five Intrapreneurial Characteristics: The 5 Ps

The intrapreneurial phenomenon found its way into business, education, and library literature as evidenced in professor and entrepreneur Kevin C. DeSouza's explanation of the essence of intrapreneurship: "an individual's ability to be inventive and entrepreneurial within the parameters of an organization. . . . Being intrapreneurial requires a focus on commercializing ideas to arrive at solutions that customers value."4 Commercializing simply means the process you take to turn your idea into a product or service available to your clientele. DeSouza additionally noted that while intrapreneurs could be—and in fact were—just as driven and excited about their ideas as entrepreneurs, these internal change agents elected to use their talents within their organization's structure while making use of their organization's resources.5

Intrapreneurs were further examined by Donald F. Kuratko, professor of entrepreneurship at the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University (Bloomington), and Richard M. Hodgetts, Suntrust professor of strategic management at Florida International University. Kuratko and Hodgetts clearly equated the concept of intrapreneurship with innovation. They stated that intrapreneurs receive "organizational sanction and resource commitments for the purpose of innovative results. The major thrust of intrapreneuring is to develop the entrepreneurial spirit within organizational boundaries, thus allowing an atmosphere of innovation to prosper."6 The key point here is within the organizational boundaries. Those who dismiss and sabotage others' innovative ideas, work to disrupt the organization, or use the cover of innovation or intrapreneurship for their own purposes are pseudo-intrapreneurs or rogues. These individuals are not true change agents and in the end their behavior will have negative consequences for their clientele, the organization, and themselves.

Successful entrepreneur and author Guy Kawasaki further expounds on the organizational boundary point. Kawasaki, who was one of the intrapreneurs responsible for the success of Apple's Macintosh computer, devoted a mini-chapter in his self-help book The Art of the Start to the art of internal entrepreneuring. Kawasaki discussed how intrapreneursÊ main motivation should be the improvement of their organization. Within an organization, intrapreneurs must display qualities that allow them to use finesse, diplomacy, and a certain amount of charm to sell a new idea to their colleagues. It's not about forcing your will on others. It is about persuasion and collaboration—both up and down the organizational structure. If your idea is a good one, others will support you, but only, as Kawasaki notes, "if you're doing it for the company, . . . not if itÊs for your personal gain."7

Kawasaki also noted that truly effective intrapreneurs keep track of new paradigms and hold ideas ready to address issues quickly. They are people who are proactive, not reactive. They are the ones who walk into the boss's office and say, "Hey, I've got this idea." They question, but more importantly they offer solutions. They work with, not around or through, others. They are optimistic, not negative. They cultivate ideas and their colleagues. Ask yourself: Do you keep abreast of current developments in technology? In your community? In library trends? Do you really see what you can offer your clientele? Are you willing to support your colleagues in a new effort that can really improve services? Are you collegial? Are you willing to keep your great idea in check until the time is ripe for commercialization?

Remaining proactive and engaged leads not only to personal organizational success, but to personal satisfaction and a positive work environment. Manipulative tactics, such as bullying, going it alone, destructive criticism, and whispering campaigns, have no place in an innovative workplace. No one should underestimate or demean the value and abilities of a fellow employee, manager, or even the big boss. The excuse that "she's too old to really understand technology" or "I just don't agree with this project so I'll not support it" degrades the entire intrapreneurial process. Remember that it is up to you, the intrapreneur, to generate excitement for your innovations and ensure that people at all levels and ages are capable of becoming meaningful intrapreneurs.8 One size does not fit all.

Not surprisingly, as librarians embrace the concept of intrapreneurship, and even recognize themselves as intrapreneurs, they have promoted the concept through conferences and webinars. In 2009 the first Entrelib: The Conference for Entrepreneurial Librarians was held, promoting internal change agents through conferences and webinars. In 2014, the conference focused on risks and change and in 2016 enticed innovators with the conference title "Imagine the NEXT!"9

The environments of entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs are different. Intrapreneurs choose to stay within an organization; they have stability in terms of job and pay; they do not need to put their own finances on the line to launch a new product or service. That said, intrapreneurs contribute their own time and may put their reputations on the line to advance a change they truly believe in and one that fits into the framework of their organization. Indeed, intrapreneurship can lead to increased job satisfaction for those who embrace it. Matthew G. Kenney, writing about academic entrepreneurship and faculty job satisfaction, notes that "experienced academicians are increasingly more interested in pursuing innovative career opportunities as it leads to increased recognition in their field." Engaged and satisfied employees create greater stability in the organization as well as greater innovation.10

Enter the intrapreneur: a change agent who shares many of the characteristics and motivations of an entrepreneur, but who works within a large or small institution and relies on that organization for financial remuneration and organizational support. Motivationally, both intrapreneurs and entrepreneurs are driven more by a passion to create rather than by the desire to make more money. For librarians and others working in libraries, establishing new services within the structure of their organizations, and, perhaps more importantly, envisioning creative ways of applying their unique perspectives and skills in an expanding context reflects this creative zeal.

Certainly, with the rise of a global economy, immediate access to knowledge and communications, and the rise of for-profit and nonprofit competitors, library intrapreneurs are revising old services and doing many things in new ways. Continuous innovation is the key to success, especially in large organizations that can become bogged down in bureaucratic red tape and cannot adapt quickly. Even while legacy services are being maintained, innovators can pursue new ways and means of providing services (see Figure 2.2).

The Diamond Law Library at the Columbia Law School provides an example of an access fee-based service. Upon payment of suitable fees, the library offers those outside of their standard clientele access to several important collections, a document delivery pay-as-you-go service, and a subscription service allowing local subscribers who pay an annual fee, such as law firms or companies, access to the law library collections and other privileges.12 Other traditional sources of library fees include rental of rooms, sales of withdrawn books and other materials, photocopy charges, sale of digital storage media, and access to specialized services or databases.

Not all fee-based services are successful or even marginally cost effective. Where benefits are not evident, services can and should be discontinued. In the early 1990s, the library at the University of Hartford, Connecticut, conducted market research and pilot projects and decided to launch a fee-based electronic information service called Corporate Information Services for off-campus clients. The monetary investment in the project did not merit its continuation and the library cancelled the service after just two years. While perseverance is a good trait in an entrepreneur, mistakes are made and it is admirable to recognize those mistakes and correct them, sometimes by terminating an idea and moving on.13

Still, some extra money can be a welcome outcome. When Mindy Reed, a librarian at the Austin (Texas) Public Library, created a permanent bookstore and upcycling facility called Recycled Reads, she implemented new and innovative uses for discarded library books.

Figure 2.2: Change Agent in Action11

Reed, a recipient of the Movers and Shakers 2015 Innovators Award from Library Journal, based her idea on the simple question of how to do something better. It was a natural for Reed, whose background was corporate marketing and management. Any profits generated from book sales go to the library.14

Another good example of a win-win intrapreneurial project was the provision of library services, for a contractual fee, to young educational institutions offered by Steely Library at Northern Kentucky University. Service agreements were negotiated between Steely Library and two customer institutions: a new community college, and a new branch campus of a for-profit institution. The resulting contracts allowed the institutions to immediately provide their faculty and student bodies with access to extensive information resources at very little cost. Use of Steely Library's established collections and document delivery and interlibrary loan services allowed the two customer institutions to start building their own library services on the public services side rather than investing in collections and technical services. When the two institutions were better established, they were able to more easily bring library support in-house. In the meantime, Steely Library had received substantial revenues through the contracts.

Always be sure that you can articulate the benefit accruing from any intrapreneurial effort, and most importantly, work to derive benefits for multiple constituencies, including the library, to those you are providing services to, and potentially to other third parties. A new service may provide users with better access to information, enrich the lives and experience of employees, and improve the standing and credibility of the library, opening up possibilities for continuing or increased support from the parent organization.

An example of this can also be found in Steely Library at Northern Kentucky University. The creation of a bachelorÊs degree program as well as a professional continuing education program in library science was an innovative, and perhaps counterintuitive, development within an academic library. However, it has provided benefits to a number of constituencies, including library staff from libraries throughout the country (professional education), library users served by graduates of the programs (stronger library services), Steely Library faculty (teaching opportunities, renewal of skills, added compensation), the library itself (revenue, improved librarian skills, opportunities for support-staff development, enhanced profile on campus), and the university (increased enrollment, revenue). In addition, the new programs have been leveraged as the basis of two major statewide grant-funded programs, each providing additional benefits to a wider audience. This is a true win-win situation.

Ultimately, intrapreneurs agree that their hard work, risk, and vision are worth the end result. The main point is to take action, finish the project, and make a difference. Change agents see opportunities where others see only obstacles. An idea may begin as a good intention, but if it is not developed and put into action with recognizable results, it remains only an idea. Management expert Peter Drucker noted that non-profit institutions, such as libraries, bring about change in people through services by creating "habits, vision, commitment, knowledge" and "become a part of the recipient rather than merely a supplier."15

As library professional and 2012-2013 Association of College & Research Libraries president Steven J. Bell observed, "librarians often fear success more than failure, as success means having to do the real work to make an idea come to fruition."16 Author and entrepreneur Seth Godin echoed Bell's remarks and stated that the difference between success and failure comes after the idea is introduced. He asked, "Did you finish?"17

The ability to keep on track, focus on, and finish a project is a key component of the successful change agent. Innovation and intrapreneurship benefit all of those involved, from you, the intrapreneur, to your organization and its mission, your colleagues, your leaders, your community, and especially your clientele (see also Figure 2.3).

Self-confidence is an important factor in successfully becoming an intrapreneur. The greatest barrier to personal success is a lack of confidence in one's self. Everyone suffers from occasional self-doubts and anxieties. What will be the consequences of one's actions? The key is to overcome these doubts, anxieties, and fears by putting them into proper perspective. Begin by acknowledging your greatest self-doubt or fear. Is it

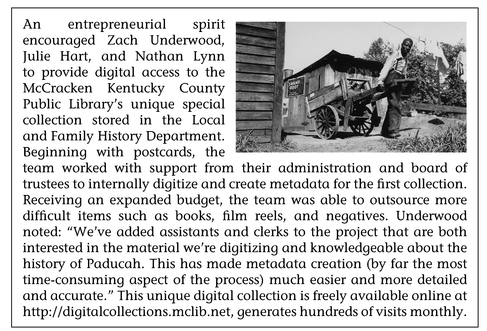

Figure 2.3: Swamp Roots18 Source: Photo courtesy of the McCracken County, Kentucky, Public Library Local and Family History Department, Mary Wheeler Collection. Features roustabout Uncle John at work. According to Underwood “Roustabouts were African-American river workers, and Mary Wheeler, of Paducah, was famous for collecting and transcribing their work songs. Uncle John is credited with the song ‘Katie an’ the Jim Lee Had a Little Race.’”

Or are you frightened of success? What if your project becomes a roaring success and you are suddenly propelled outside of your comfort zone? As entrepreneur Seth Godin writes, "success can be just as fraught with danger as failure, because it opens more doors and carries more responsibility."19 Success means that you have to complete or develop the project, possibly replicate it, and continue to take risks and fight battles. It may also mean leaving your comfort zone and the confines of a familiar, if sometimes monotonous, work environment and heading into a more challenging and ever-changing role. Success also may mean stepping out into the community and engaging others in support of your idea. Success may mean more work. People say they want change, but are they really willing to implement it? How can intrapreneurs overcome fear?

Begin by addressing the fears and conquering them. Start with a sense of cold, hard reality. What is the worst thing that can happen? Address your excuses by listing and then countering them. Do not dwell on reasons for not beginning a project. Focus on the rewards for success rather than the consequences for failure. And above all, remember that your fears are not unique. All intrapreneurs have fears and doubts. The trick is to overcome them.

In spite of what may seem like negatives, success, with or without self-doubt and fear, remains one of the motivators intrapreneurs embrace in their quest to introduce innovative and policy- and organization-changing ideas. Intrapreneurs are self-starters and are more than capable of tapping into their own internal motivators.

The rewards of intrapreneurship can take many forms, including personal recognition, awards (such as those Movers and Shakers highlighted in Library Journal), more authority and responsibility, job flexibility, promotions, and, yes, additional compensation. However, the greatest reward for most intrapreneurs is the knowledge that their idea has been brought to life and that it benefits their organization, clientele, and community. Their efforts have made a difference.

Intrapreneurs take action. . . . True intrapreneurs are trustworthy, encouraging, open, positive, supportive, and give credit where it's due!

—Howard E. Haller, Founder and Chief Enlightenment Officer of the Intrapreneurship Institute20

Our present system of management structure and decision distribution is safe and comfortable, but it doesn't work. . . . The discipline must come from within, because . . . nobody else cares what we do, only how much we spend. Many in our user communities, of course, would just as soon we changed nothing that is already comfortable. That is unacceptable, because it trivializes our own professional role.

—Herbert S. White21

The first commandment in Pinchot's original "The Intrapreneur's Ten Commandments," referring to corporate entrepreneurs, rather dauntingly reads: "Come to work each day willing to be fired." He amends this extreme directive a bit with additional commandments: "Don't ask to be fired; even as you bend the rules and act without permission, use all the political skill you and your sponsors can muster to move the project forward without making waves."22 You want to become your organization's intrapreneur-in-residence, not an unemployed librarian. Indeed the authors of Verbal Judo caution: "the moment you stop thinking like your employer, you'd better start looking for another job ."23 Simply stated, put your organization first. It is not all about you. "Intrapreneurship isn't about grabbing the limelight, building an empire or using the company to catapult out but is more about turning an idea into an opportunity for the company."24

Pinchot further suggests that intrapreneurs "ask for advice before asking for resources," "express gratitude," and perhaps most importantly, "build your team; intrapreneuring is not a solo activity" as well as "share credit widely."25 Indeed, just because you think you have the greatest idea since the online catalog does not mean that those you work for and with will be convinced. You are the one who is responsible for convincing others!

Part of the job of persuading others rests on your personal reputation within the organization and externally with your clientele. Personal trust and respect stem from working collegially with others, both within and outside of the organization, and advocating for your organization. Ask yourself some essential questions:

How you handle conflict is a key component to success. Intrapreneurs who continue to push an idea out of sheer stubbornness without considering constructive criticism and revising the concept are usually not successful. Do not look at the intrapreneurial process as a win-lose scenario. If you have to modify, postpone, or terminate a project, this does not represent a loss for you personally. Rather, being able to adapt, being open to criticism and change, should be one of your primary objectives.

In addition to remaining open and responsive to your organization's needs, every intrapreneur's toolbox should contain the fine art of gracefully accepting "no." When intrapreneurs say "no" they oftentimes wonder what part of that statement is incomprehensible to others. When others say "no" to intrapreneurs, they question the decision and may frequently decide that they should never have to accept "no" for an answer. Taking that advice literally can place an intrapreneur in a very risky position.

First, learn to understand the nuanced meanings of "no." The organi-zation's administration is charged to manage resources prudently, to set overall direction, and to coordinate the mission with that of a parent organization. The administration must also weigh proposals from throughout the organization to match them with the organizationÊs ongoing mission and must balance between competing ideas. Not all ideas can be funded or supported at the same time, particularly if they (1) are contradictory, (2) require the same resources, (3) do not meet the organization's mission. If you decide to proceed without asking, and effectively convincing those people who have the power to reinforce "no," be prepared to be reprimanded, disciplined, or dismissed.

On the other hand, "no" can sometimes mean "not now." In that case, taking the time to better prepare your case, doing background work, proceeding with experiments—possibly on your own time—will enable you to better persuade management when the moment is ripe. Remember that effective intrapreneurship must welcome collaboration between an employer and an employee who both have the best interests of the organization in mind.

If you hear an unqualified "no" once too often you may feel that management is simply not open to new ideas, and it may be time to look for another job. Moving to an organization that encourages change from one that does not can pay big dividends in job satisfaction and reduced stress. Making an organizational move and also moving up the administrative ladder gives you a better platform to implement your idea.

By championing an idea intrapreneurs may encounter push-back and open themselves to a variety of risks. Ideas, especially organization-changing disruptive ones, may place the existing organization, clientele, operating policies, and power structures at risk. Unlike the entrepreneur, however, the intrapreneur does not endure personal financial risks, barring, of course, getting fired from his job! Intrapreneurs tap into the resources of their organizations and still receive a paycheck. When entrepreneurs fail, they may face personal bankruptcy as well as the loss of their idea and company. When intrapreneurs fail, the organization absorbs the costs of that failure. Nonetheless, intrapreneurs must be genuine risk takers. In many cases the amount of risk with which they feel comfortable will affect the degree to which they will succeed at intrapreneurship. Other factors influencing risk taking and its impacts include the organizational culture of your institution, which we will discuss more fully in Chapter 4.

Generally speaking, however, it is risk versus reward that characterizes a key difference between the psyche of intrapreneurs and entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs elect to live in a risk-laden world that swings between huge rewards, usually monetary, on the one hand to enormous losses, also monetary, on the other. Intrapreneurs freely choose a steady paycheck within a stable and established organization with little expectation for large financial gains, although they may risk their own reputation within the organization. They work to achieve intrinsic gains rather than monetary rewards. While entrepreneurs sacrifice their time as well as their finances, intrapreneurs take risks with their own time as well as the organization's time—both precious commodities. In many ways, perhaps the most important sacrifice of all is time.

Once you acknowledge that your innovation is important assess the risks or potential costs to you personally. Are you comfortable risking something that you value highly, such as your standing in the organization or your free time, to see your idea implemented? If the answer is "yes" then it is time to assess what risks or costs most affect library intrapreneurs. As noted above, a major potential cost for many intrapreneurs is time, more specifically, the extra unpaid overtime you, the intrapreneur, will put into researching and defining the project while competently maintaining all duties as assigned. It also means taking the time to understand the big picture for your organization and how people, products, services, and internal and external influences interrelate. Bottom line: it means extra work!

Additional work and expending extra time are two key components of the risks and sacrifices an intrapreneur will accept to pursue her innovation. When the director of libraries at a major public university in the Southwest offered librarians the opportunity to learn new skills by paying for classes, many were reluctant to take up the offer. Why? It would cost their time, time in addition to their regular job duties. After all, those supporting the general consensus chanted: "we should be able to learn everything we need to learn during the work day." Others embraced the offer and donated their own time to attend classes, do homework, and learn new skills. When a manager who headed up one of the libraryÊs departments took up the challenge, she made the hourlong drive to a nearby community college for night classes to learn a new concept: online manipulation of images. Today, multiple apps and platforms make this an easily accessible skill, but in the late 1980s, this was not the case. Her new skills led to innovative work on physical touch screen kiosks in consultation with people inside and outside of the library. The result was that the library introduced a unique new product that predated the media-rich environment that we now experience through the Internet.26

So where does all this leave the budding intrapreneur or change agent? You already have a full plate. You are the dreamer, an innovator, the one who knows that change is needed, yet feels most comfortable working within your organization. You, as the library intrapreneur, desire change, but you are not quite sure if you want to put in the time to make it happen—not quite sure where to start. We'll go over many of the details, but remember that Pinchot characterized intrapreneurs as the "dreamers who do." Intrapreneurs dream and collaborate with others to make their dream a reality.27 Figure 2.4 illustrates the characteristics of successful change agents.

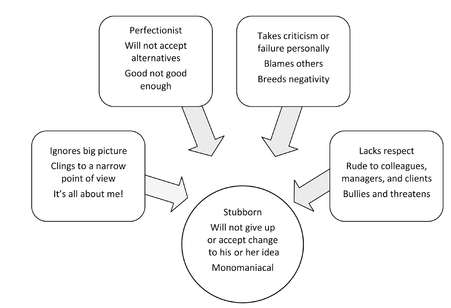

Intrapreneurs and change agents are not that arrogant and overbearing colleague with a plan that is better than anyone else could ever construct. They are not the incarnation of that glamorous, successful, and rather fictitious, billionaire entrepreneur who runs roughshod over everyone and everything in pursuit of a single goal. While you can certainly stretch the imagination, push the envelope, and think outside the box, never forget that everyone has the ability to be creative, and without support in an organization your innovation may face an early demise. Instead of stepping on toes and bruising heads, why not inspire others to join you in bringing your innovation to light? If you are an intrapreneurial manager, the greatest triumph is to build buy-in from your employees. Encourage them to take your idea and develop it as their own. What you gain in quality and satisfaction will more than compensate you for lack of credit or loss of control over your idea. They may even make it better. Figure 2.5 illustrates the negative characteristics that could derail any change agent.

Figure 2.4: Successful Change Agent Characteristics

Figure 2.5: What Change Agents Are Not

Talent that cannot be shared, duplicated, distributed, or leveraged is not nearly as valuable as talent that can.

Mike Myatt28

Success for a library is always defined in terms of the community served. . . . A library cannot be successful apart from its community.

Andrea D. Berstler29

Virgin Group founder Richard Branson remarks, "My definition of success? The more you're actively and practically engaged, the more successful you will feel."30 Being engaged with your job and your talents are key components not only to success, but to personal and professional contentment, but how do you measure success?

That said stress and conflict are a part of an intrapreneur's existence. Intrapreneurs must work within competitive systems to create, sell, and market their products or services. Seth Godin, author and entrepreneur, promotes the concept that through your own efforts, passion, and commitment you can become a linchpin rather than a cog in your workplace. Even these two terms hark back to the industrial age. A cog in the machine is a part of a gear or wheel that is turned by other forces; the linchpin holds the cogs together.31 Good advice for the budding change agent: be the best you can be, but remember that no one is indispensable and even if you are the most innovative person in the world, if you abuse your position, people will not want to work with you to achieve your goals.

Mike Myatt, leadership advisor to Fortune 500 CEOs and boards, comments that nobody "and I mean nobody is indispensable. I don't care who you are, what role you play, or what your title is—if you perceive yourself to be indispensable, you are setting yourself up for a very rude awakening. I was once reminded that the graveyards are full of indispensable people."32

No one need be satisfied with being a cog in the machine. This begs the question whether managers can also be intrapreneurial? The answer is an emphatic "yes." Those with vision outside of the conventional mold create the intrapreneurial culture within an organization that is crucial to innovation.

No matter what your status is in your organization, no matter how big or small your library, no matter how many are on staff, no matter what type of library or organization you work in, no matter how dismal the

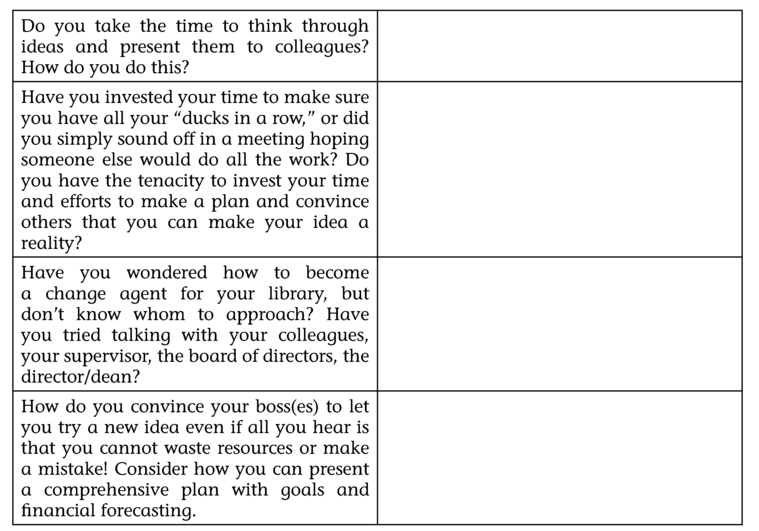

Figure 2.6: Intrapreneur Questions

budget, you can become an entrepreneur-in-residence, an intrapreneur, a change agent, a linchpin rather than a cog. Invest time in yourself, your innovation, and your organization. Let's start with a number of general questions that you need to ask yourself as you assess your abilities and commitment. Use Figure 2.6 to answer these questions. You may answer "yes" or "no," but be sure to explain why you did.

Based on your answers in the questionnaire, are you invigorated and inspired? Hopefully, you are more energized and anxious to consider your next steps for success. Keep focused and don't allow outside influences or a crisis or catastrophe to be the only source of change in your organization. Focus on what you, the intrapreneur, can do to make a difference in your organization. In Chapter 3, we will look at some ways to focus and enhance your creative genius and help you to become the change agent that truly makes a difference.

1. Douglas S. Brown, "Unhappy at Work? Be an Intrapreneur." Community Content, May 13, 2013, http://www.wired.com/2013/05/unhappy-at-work-be-an-intrapreneur/. Post University is in Waterbury, Connecticut.

2. Gifford Pinchot, III, and Elizabeth S. Pinchot, "Intra-Corporate Entrepreneurship," Intrapreneur.com, Fall 1978, http://www.intrapreneur.com/MainPages/History/IntraCorp.html. Pinchot cofounded the Bainbridge Graduate Institute in 2002, which was renamed Pinchot University in 2015. Their mission was and is to "change business for good." They offer certificates and MBAs in sustainable business along with the Center for Inclusive Entrepreneurship program. For more information, visit the school's Web site: http://pinchot.edu/.

3. Gerald C. Lubenow, "Jobs Talks about His Rise and Fall," Newsweek, September 29, 1985, http://www.newsweek.com/jobs-talks-about-his-rise-and-fall-207016.

4. Kevin C. DeSouza, Intrapreneur ship: Managing Ideas within Your Organization (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 5.

5. Ibid., 34.

6. Donald F. Kuratko and Richard M. Hodgetts, Entrepreneurship: Theory, Process, Practice, 7th ed. (Mason, OH: Thomson Higher Education, 2007), 55.

7. Guy Kawasaki, The Art of the Start: The Time-Tested, Battle-Hardened Guide for Anyone Starting Anything (New York: Penguin, 2004), 20.

8. Dan Schawbel discussed the importance of intrapreneurship for mil-lennials as "an opportunity to develop their leadership skills while inspiring change. For millennials who are entrepreneurial, but are still paying back student loans and don't have access to mentors or capital, intrapreneurship is the perfect solution. By leveraging internal resources and a corporate brand, millennials can make a big impact even at the start of their careers—and that's exactly what they want. When intrapreneurs are successful, companies reap the benefits too." Dan Schawbel, "Why Companies Want You to Become an Intrapreneur," Forbes, September 9, 2013, http://www.forbes.com/sites/danschawbel/2013/09/09/why-companies-want-you-to-become-an-intrapreneur/.

9. Entrelib: The Conference for Entrepreneurial Librarians, http://entrelib.org/.

10. Matthew G. Kenney, Academic Entrepreneurship: The Role of Intrapre-neurship in Developing Faculty Job Satisfaction (Saarbriicken: VDM, 2009), 2-3.

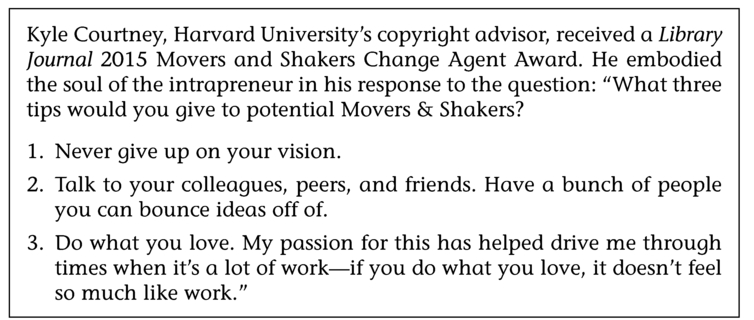

11. Lisa Peet, "Academic Movers 2015: In Depth with Kyle Courtney," Library Journal, June 4, 2015,http://lj.libraryjournal.com/2015/06/people/academic-movers/academic-movers-2015-in-depth-with-kyle-courtney/.

12. Diamond Law Library, "Fee Based Services," Columbia University, c. 2016, http://web.law.columbia.edu/library/services/fee-based.

13. Elizabeth A. McDaniel and Ronald H. Epp, "Fee-Based Information Services: The Promises and Pitfalls of a New Revenue Source in Higher Education," CAUSE/EFFECT (Summer 1995), 35-39.

14. "Up with Upcycling," Mindy Reed, Movers & Shakers 2015—Innovators, Library Journal, March 17,2015, http://lj.libraryjouinal.com/2015/03/people/movers-shakers-2015/mindy-reed-movers-shakers-2015-innovators/.

15. Peter Dracker, Managing the Non-Profit Organization: Practices and Principles (New York: Harper Collins, 1990), 39.

16. Steven J. Bell, "The Librarian Entrepreneur? Demystifying an Oxymoron," Against the Grain 21, no. 4 (2009), 20. Check Bell's Web site: http://blendedlibrarian.learningtimes.net/.

17. Seth Godin, Linchpin: Are You Indispensable? (New York: Portfolio, 2010), 136.

18. Zach Underwood, e-mail messages to authors, June 23,2015, and July 1, 2015.

19. Seth Godin, The Icarus Deception: How High Will You Fly? (New York: Portfolio/Penguin, 2012), 183.

20. Howard Edward Haller, Intrapreneurship. The Secret to: Ignite Innovation, Recruit and Retain Key Employees, Unlock New Product Creation, Expand Market Share, Sustain Higher Profits, Improve Job Satisfaction (Coeur d'Alene, Idaho: Silver Eagle, 2014), 32-3. Check Haller's Web site: http://www.intrapreneurshipinstitute.com/.

21. Herbert S. White, "Entrepreneurship and the Library Profession," Journal of Library Administration 8, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 27.

22. Gifford Pinchot, III, "The Intrapreneur's Ten Commandments," The Pinchot Perspective, November 20, 2011, http://www.pinchot.com/perspective/intrapreneuring/.

23. George J. Thompson and Jerry B. Jenkins, Verbal Judo: The Gentle Art of Persuasion (New York: William Morrow, 2013), 54.

24. Anastasia, "Intrapreneur," Entrepreneurial Insights, March 25, 2015, http://www.entrepreneurial-insights.com/lexicon/intrapreneur/.

25. Gifford Pinchot, "The Intrapreneur's Ten Commandments," The Pinchot Perspective, November 20, 2011, http://www.pinchot.com/2011/11/the-intrapreneurs-ten-commandments.html.

26. Sharon Almquist, Head, Media Library, University of North Texas Libraries, took classes at Collin County Community College and Richland College.

27. Gifford Pinchot, "Innovation through Intrapreneuring," Research Management 20, no. 2 (March-April 1987), http://www.intrapreneur.com/MainPages/History/InnovThruIntra.html.

28. Mike Myatt, "Seth Godin's Linchpin Theory: Sound Advice or Career Suicide?," Forbes, November 29, 2011. Leadership, http://www.forbes.com/sites/mikemyatt/2011/11/29/seth-godins-linchpin-theory-sound-advice-orcareer-suicide/.

29. Andrea D. Berstler, "Running the Library as a Business," in The Entrepreneurial Librarian: Essays on the Infusion of Private-Business Dynamism into Pmfessional Service, Mary Krautter, Mary Beth Lock, and Mary G. Scanlon, eds. (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012), 30.

30. Richard Branson, "My Definition of Success," Virgin, http://www.virgin.com/richard-branson/my-definition-of-success.

31. Godin, Linchpin: Are You Indispensable?, 136.

32. Myatt, "Seth Godin's Linchpin Theory."