A status quo attitude will render an organization ineffective and condemn it to obsolescence and lack of support.

—Library and Information Center Management1

Pitching isn't only useful for raising money—it's an essential tool for reaching agreement on any subject. Agreement can yield many outcomes: management buy-in for developing a product or service, securing a partnership, recruiting an employee, or securing an investment.

—Guy Kawaski, Art of the Start2

"'The time has come,' the Walrus said, 'to talk of many things: Of shoes—and ships—and sealing-wax—Of cabbages—and kings—And why the sea is boiling hot—And whether pigs have wings.'"3 Like Lewis Carroll's walrus, it is time to address several crucial ways to encourage the successful acceptance of your idea, such as how to pitch your idea and get support and buy-in from your organization; how to deliver an effective elevator speech and presentation; how to handle acceptance and rejection; how to create a working innovator's plan; and how to understand and integrate budget considerations into your proposal. Remember that many different people or stakeholders make up your organization: the end users of your idea, people who use the library as well as fellow employees. Simply put, it is time to campaign for your idea and select the appropriate audience for your promotion. It is time to sell your idea to those who may be eager to support a change or to those who may be risk averse. In either case, the challenge you face is to select, then impress, inspire, and convince your audience even if you are not sure how, or whether, the group will accept your idea. Your goal is to create enthusiasm, not aversion; to soothe and appeal to risk-averse mentalities; and to never lose sight of your primary objective: your plan for innovation.

Libraries are dynamic organizations, but as a rule, innovative ideas do not fit effortlessly within existing organizations. Instead, as discussed in other chapters, change agents must understand the organization, its goals and objectives, strategic plans, vision and mission, internal and external clientele, and the community it serves. They need to know the current state of the organization, know the internal and external forces that can affect decisions, understand budgeting and personnel concerns, and be able to see the big picture. In other words, be prepared to think like a manager. With that accomplished, the intrapreneur may then seek out a sponsor, a person who has the authority to run interference for the intrapreneur and assign resources and secure permissions. The intrapreneur then is free to build his advocate base by selling the idea to the right people at the right time. One effective method for gaining support is the elevator speech. Once you capture your listener's interest with a short but passionate appeal, you can then arrange a time to talk at length.

You are a busy person. So are your supervisors and peers. Why waste their time as well as your own with long-winded explanations that detail, with excessive jargon, every single aspect of your idea? Leave those details for the innovator's plan—also known as a business plan. Begin by synthesizing your idea into a 30-60-second (100-250 words or fewer) explanation or advertisement. It is challenging to synthesize a whole plan into that short timeframe, but ultimately gratifying. It allows you to express the most important reason for your idea while you seek to persuade others to not only listen, but invest their time and energy. You want to spark others' interest in your project. Never assume that because the idea is of maximum interest to you, it will also be so for others. An effective elevator speech makes the listener ask, "Tell me more about this idea" or "Let's get together over coffee tomorrow because I want to know more."

Your elevator speech must be brief and to the point because research indicates that many listeners lose interest after 30 seconds. Some studies even show that the average human has a shorter attention span than the average goldfish: humans eight seconds, goldfish nine seconds.4 TV or radio commercials average 30 seconds, which is also the average length of an elevator ride. You have a captive audience in an elevator, but only for a short period of time: about the amount of open time your supervisor might have on a busy day. Although some experts might allow up to a two-minute speech, most agree that short, passionate, cogent, and interesting pitches are the best. Remember, an elevator speech works to generate initial interest and create advocates for your idea at both the initial phase of acceptance and later when you promote and celebrate the idea.

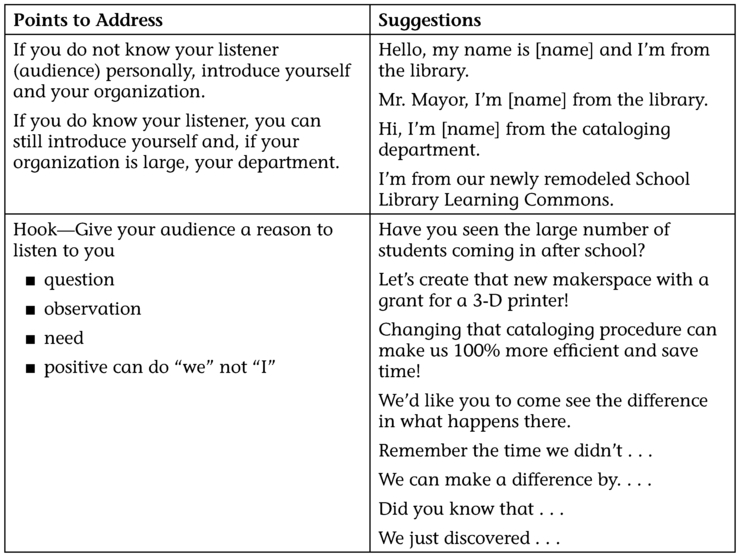

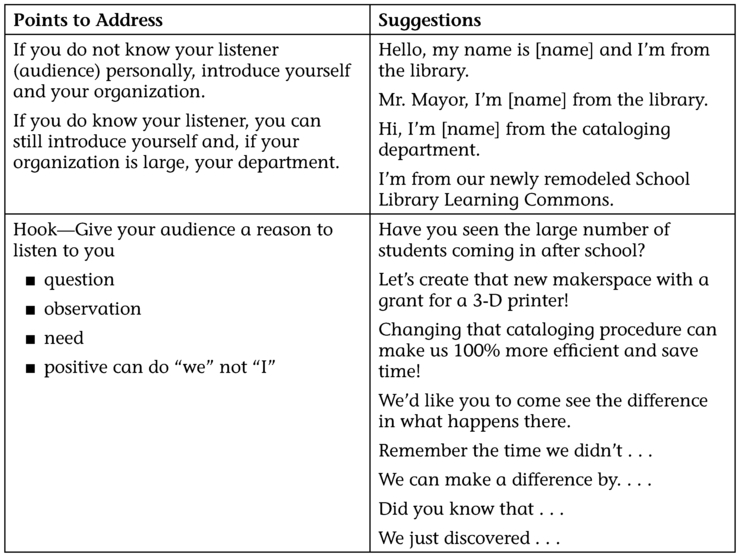

Take the time to carefully craft your speech to garner support from people in your organization. While you should change the pitch to reflect the interests of your audience, having your ideas organized can help you to get them across more effectively. Here are a few tips to help you craft an effective elevator speech:

Use the worksheet (see Figure 6.1) to improve your speech and help you work out the kinks. Ask a colleague to listen and critique your

Figure 6.1: Elevator Speech Worksheet

pitch; then start pitching to those you feel are sympathetic. As the idea snowballs, others may also take up the elevator speech in support of your idea. In smaller libraries, getting into the community and being prepared to promote your idea, and your library, at a moment's notice can enhance your chances of getting support when you most need it and least expect it.

Thirty seconds is not enough time, you argue. For many people, perhaps not, but being able to arrange your thoughts so that you can present them clearly in a short timeframe helps you to pitch even more effectively after you have captured your audience. On the other hand, what things can derail your efforts at pitching in that short a timeframe? There are several:

If you are going to turn your promotional elevator speech into a full pitch you may have to consider getting someone in authority, either within or outside of your organization, or both, to assist you with getting the idea accepted and implemented. Decide what format you will use for your pitch and then to take it to the next step.

If you are going to be successful in generating interest both within and outside of your library and are motivated, positive, and focused, you need to sell the idea to someone in the organization who can help you to realize your goals. This may be your supervisor, the library board, a dean, or director, but it is someone who has the authority to assist you with the change. Begin by working with your supervisor first to allow him to buy into your plan. Provide the information your supervisor will need to make an informed decision. For example, your supervisor may ask: how will you handle the extra work? If asked this question, you will need to reassure him that your project won't distract you from work already assigned. Be careful how you answer. If you appear to be too busy, your supervisor may want you to put off the innovation. If you give the impression of excess hours in a day, the boss may wonder why you did not suggest this sooner or whether you have been assigned enough work to keep you busy! Explain how the innovation fits into your current workload and, if necessary, show how you will put in extra hours to make it happen because "employees who are passionate about the company, and skilled enough to implement their passion, are an invaluable asset, and will be far more useful to a company than those who simply show up to work to complete the bare minimum of what's required of them."6

Another must is to put yourself in your boss's shoes because everyone has to justify changes to someone. Clearly articulate the benefits that come from your proposal. Seek to create a win-win environment for everyone involved. Susan Inouye, an executive coach, recommends that if "we let go of our egos and look towards our boss as a mentor in the development and implementation of our idea and are willing to share the credit with them, the more invested they become. We must remember that their contributions are necessary to get it done."7

What if the boss says "no"?

Try to find out if this is "no" at this time or a final "no." Be clear about the meaning of "no." Ask for feedback and consider the following:

With the answers to these questions you will know whether to revise and return or give up the project altogether.

As part of the pitching process, some authors suggest that in order to sell your ideas internally, one format you might consider is to create a video with colleagues and/or clientele. Interview and create a video with people who support the idea and learn how its adoption will benefit them. The video shows your take-charge attitude and ability to get things accomplished. You have taken your time and effort to make a change.8 Above all, be respectful of others' time and edit the video to a reasonable length—no more than three minutes. Use the video to make your idea pop and generate excitement for a change.

When you are ready to take your pitch outside of the organization, usually with your supervisor's blessing, consider asking to be invited to a meeting of the local Rotary Club, Kiwanis group, school board, PTA, Lions Club, or homeschool group. The easiest way to be invited to speak in your local community is to be an active member of your community and an advocate for your library. Join groups and attend meetings and let people know who you are and why you are there. You have already been using your elevator speech at every opportunity to promote your idea and the library. Encourage leaders in these groups to invite you for a longer presentation.

To develop a longer, and perhaps more formal, presentation, begin by working through a series of questions and providing answers that will serve as the outline for the presentation. Use a feasibility study to help flesh out the outline. Consider these key points.

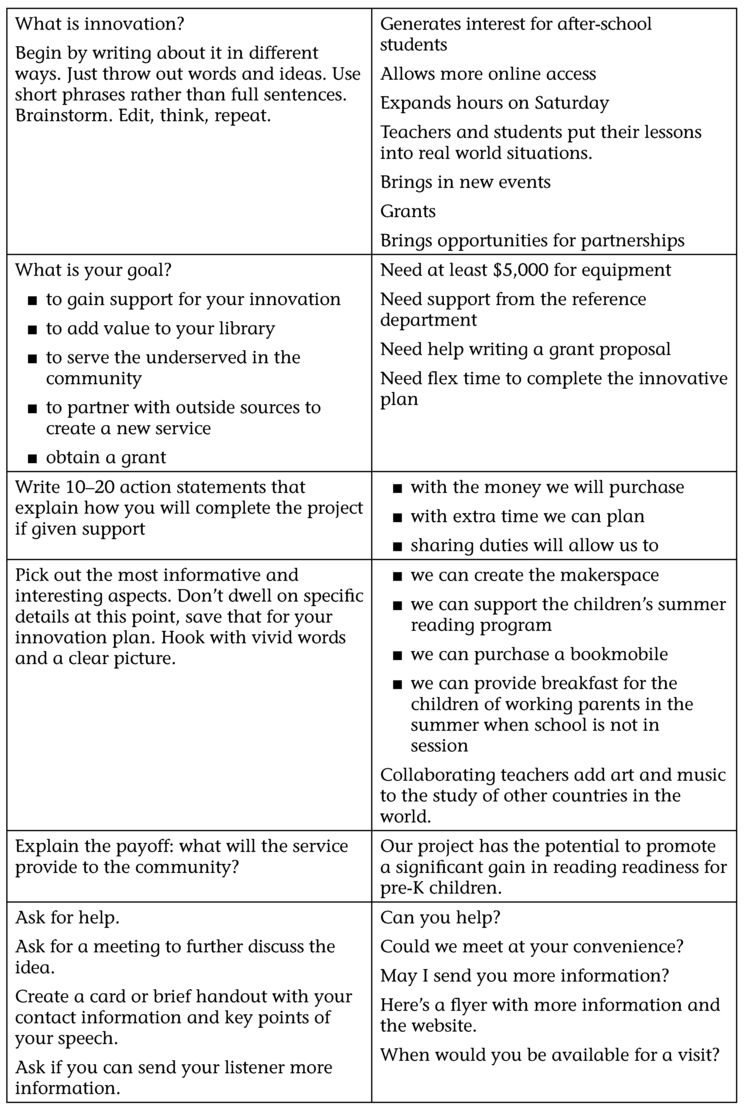

How many of us have sat through very long and very boring presentations? In trying to win support and create ambassadors for your idea, don't fall into the trap of making a boring presentation. If you do choose to make your pitch presentation using PowerPoint, PREZI, or Google Slides,9 consider the following. Guy Kawa-sakiÊs advice is 10 slides, 20 minutes, 30-point font for the text. Use pictures, bullets, and diagrams to make your point, and try to incorporate some action on your slides so that it is not a ho-hum flat text-only slide, one after another. You want to stimulate interest and concentrate on essentials, but you want to keep your audience interested. Keep some slides in reserve with greater details so that if asked you have them ready to answer with statistics. Many audiences love details, but you do not want to get bogged down in implementation details at this point. Even if your potential audience gives you an hour, aim for 20 minutes to leave room for discussion and questions.10 The question and answer section is as important as the pitch. Use the checklist worksheet in Figure 6.2 to polish your presentation.

Figure 6.2: The Pitch: Slide Presentation Checklist

What if the audience says "no"? Sometimes you have to be patient. Evaluate your plan and pitch and consider these actions:

Don't feel rejected and definitely don't get angry; ask for advice. Is there anything we can do differently to make it work? What did I fail to include? Try to get buy-in as people add their ideas to yours. Thank those giving positive, and even negative, feedback. "Thank you for that suggestion. I can see how that will make the solution even better." For those individuals who set themselves up as an enemy and may provide personal, and in some cases unwarranted, criticism, you can sometimes turn them into advocates by directing their criticism into a form of support.

Critic: "I just think you are going way beyond your abilities and fail to understand where this organization should be going."

Intrapreneur: "Perhaps you are right about my abilities, but if you were to help out I believe we can make this a truly successful intraprise."

Critic: "Well, I may be able to help, but it's just going to so much time and effort."

Intrapreneur: "If we all work together and continue to support our library's goals, we can really make effective change. When would you like to meet to discuss this?"

The applause at the end of your presentation is thunderous. Take a few moments to bask in a job well done, but only a few minutes because now the real work begins. It is time to establish a timeframe for a pilot test so you can develop a full innovator's plan that will pave the way for implementation of your accepted idea. This small-scale trial or pilot test of the project is a great way to work out the possible glitches before developing your innovation plan. Working with a small group and learning of any possible problems so you can fix them before you inadvertently build a potential problem into the full-scale plan is a smart move. This is especially true with radical projects that may involve changes in personnel or key programs. Based on feedback from the smaller group, you could revise the project plans, if needed. Some parts of it might have to be removed, while other processes may have to be added. This gives you useful results quickly and with a minimum of personnel or monetary expenditure. It strengthens your project and helps to create value.

On the other hand, if the project is seriously flawed, the pilot test will point out these challenges. This may mean that it is not the right project for your clientele right now. Create your test group from a diverse group while considering who will make the best test group. You may want to invite some wild cards, people who don't fit the established norm, to participate in the test especially if you are planning radical change. Schedule some time to meet with your test group, either individually or in groups. Listen to what they have to say, and write up a document describing the pros and cons of your idea. Chances are you will receive even more ideas for innovation as a result. The pilot test will also allow you to assemble a team that can use hard data to move a project forward.

With pilot test results and feedback, you are ready to start your innovator's plan.

The innovator's plan is loosely based on the type of business plan entrepreneurs use to build legitimacy for their companies. Katz and Green13 explain the classic business plan with the major characteristics of a company, such as product or service, the overall industry and market it is working in, how it will operate, and financial considerations detailing how it will make money. A business plan also provides internal understanding for those involved in the business; it explains how the business operates and allows entrepreneurs to organize their thoughts regarding the business and its purpose and internal operations. Katz and Green emphasize that the plan must explain how the business will function. Like the business plan, the innovator's plan explains the proposed product or service, the clientele who will be served, and how it will operate. Of course, rather than talking about how the project will make money, the innovator's plan discusses sustainability of the innovation since libraries are generally not profit-making concerns.14 Depending on the innovation, the change agent may choose to follow a strict plan or adapt the general plan to meet her needs.

The innovator's plan is built on the pitch, which was in turn built on client feedback and idea generation. If your pitch was successful, your innovatorÊs plan is already partially written. Incorporate the feedback from the pitch into the plan, assemble and work with your team, and pave the way for a successful implementation.

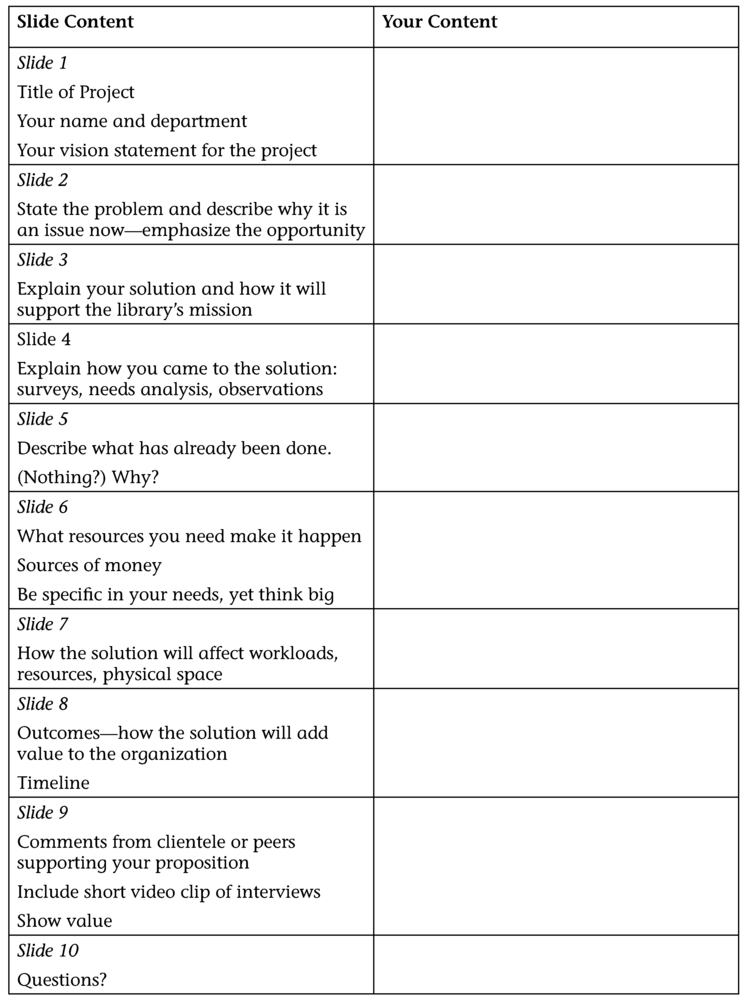

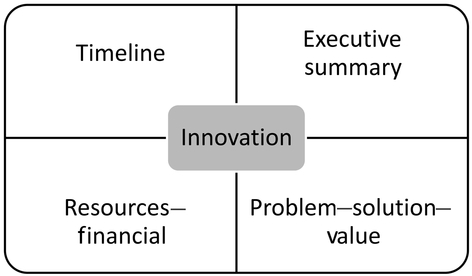

One of the most important parts of the plan is the executive summary. Many of those people interested in your project will only read the executive summary. How long should it be? Ideally between four paragraphs to two pages. Here is where you address the key points of the innovation: cogent description of the problem, the solution, the resources needed to solve it, the value created for the organization.

Figure 6.3: Key Points of the Innovator’s Plan

Other key points of the innovator's plan include support for the solution; resources needed and the financial aspects, such as what it will cost in terms of money and personnel; and timeline for implementation and review. It is generally recommended that one person write the draft of the plan. Then you can use it to work with your team, which you will assemble, as detailed in the next chapter. Working as a team, your evaluation of the plan forces cooperation and debate. The plan may bring to light details left out of the pilot project as well as new ways to perform some of the tasks. As Guy Kawasaki notes, "the document itself is not nearly as important as the process that leads to the document. Even if you aren't trying to raise money, you should write one anyway."15 Figure 6.3 illustrates key components of the plan.

At this point, you will consider how you will fund your plan. Realize that all plans require some level of resources to put them into operation. While there may be no direct financial investment, there will be personnel costs. (Staff time is worth money, and if someone is working on your project, even if it is only you, that person is not available to work on other projects or to provide ongoing services). In addition, there are opportunity costs. That is, by doing your project, other projects or operations (opportunities) may be postponed or permanently cancelled.

The realization that costs are involved in the implementation of any plan helps you to better communicate with your supervisor to request resources that will be needed. Going forward with a request for permission stating that your plan "won't cost anything" will suggest to administrators a certain level of naïveté, which will certainly damage your credibility. If you bring forward a plan which takes into account the time and labor cost (including benefits) that will be required to operationalize your plan, you will have much more credibility with your boss and upper administration and stand a better chance for getting permission to proceed. In terms of direct costs, depending on the size of the project, the state of your organization's budget, and competing needs, there are multiple ways in which the project could be funded.

When you request resources from your organization, much will depend on the level of credibility that you have earned from your administration, which heavily depends on your past interactions. Does the administration know you for your honest assessments in previous requests for resources? Are you honest in your assessments of consequences for not carrying out a proposed change? With limited resources and competing needs, it is critical that you have a strong bond of trust in place when you make your request.

If the project requires only reassignment of personnel, permission might be readily given. If your project will require actual budget allocation, the request might need to be added to the library's financial plan. Your boss may need to go to a higher level to request support. In this case, give your administration as much lead time as possible.

In many library situations, it is anticipated that librarians in academic, public, and school libraries should seek outside funding for those projects that are already not in the general budget if the project is for the near-term future. This often means that you must seek outside funding and the first place to look is grant funding.

Grant funding can be tapped to finance innovation projects when your project fits the granting agency guidelines. Grants are available from private foundations and from all levels of government. These are very competitive and not always difficult to locate.

State libraries often offer grants to public libraries through state funding projects and through their reallocation of Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA) funds. Whether those funds are available for academic or school libraries depends upon the state plan for LSTA.

While the process of grant seeking is beyond the scope of this book, you may find help in a book by Hall-Ellis et al.: Librarian's Handbook for Seeking, Writing, and Managing Grants:

In addition to capitalizing on collective skill, cooperation and teamwork foster creativity and encourage accountability among team members. With many projects to choose from, funding agencies are especially responsive to those that address documented needs in novel and creative ways.16

You may also seek out the help of a grant professional in your community. If it is to be a cooperative venture with another type of library, coordinate between grant offices. Those working in public libraries may find that their supporting municipal or county government has a grants professional on its payroll. Larger school districts or regional centers such as county offices also may have someone to help with grants, as do colleges and universities. The grants professional will bring specialized knowledge and experience to the process of grant seeking, facilitate connections with people in the granting agencies, and equally as important, contribute experience in managing grant funds and fulfilling reporting requirements.

Someone in authority in your organization will have to sign off on your application to indicate that the organization supports it. This ensures that the institution is aware of any obligations it may need to provide, such as facilities needed to carry out the project or in-kind contributions for a matching grant as well as overhead charges.

Another way to pay for innovation is by getting someone from outside of the organization to pay for it. The intrapreneur generally must tread carefully in this area since donors are jealously guarded both by library leaders and by people in the parent organization. Always make sure that you contact, get permission, and work with your administration when pursuing this approach.

Will your project result in benefits for the greater community? Are you doing something that will impact P-12 education, involving early childhood reading/learning readiness, creating a service that will connect people with or preserve their heritage? There is a constituency or a cause for each of these examples, and you might well find it easier to connect a donor with this type of special project than many of the day-to-day projects that we see in our libraries.

Most recently, intrapreneurs are beginning to turn to crowd funding to support innovation. Again, you must have a project with which people can quickly develop an emotional connection. Like the crowd funding used by entrepreneurs to fund profit-making concerns, in the nonprofit sector, the technique allows multiple small investors to pool their money to support a worthwhile and compelling project. Again, check with your institution or organization to see if a crowd-funding mechanism is already in place.

Now that you have a viable project, it is time to assemble your team and determine your place in it. Even if you did much of the preliminary alone work, you still need a team of supportive individuals who share your vision and will work together to make meaningful change in your organization.

1. Barbara B. Moran, Robert D. Stueart, and Claudia J. Morner, Library and Information Center Management, 8th ed. (Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2013), 60.

2. Guy Kawasaki, The Art of the Start: The Time-Tested, Battle-Hardened Guide for Anyone Starting Anything (New York: Portfolio, 2004), 44.

3. Lewis Carroll, "The Walrus and the Carpenter," in Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (Rathway, NJ: The Mershon Co., 1900), 66.

4. Microsoft Canada, Attention Spans-Consumer Insights (Spring 2015). 6.

5. Sam Harrison, Idea Selling: Successfully Pitch Your Creative Ideas to Bosses, Clients and Other Decision-Makers (Cincinnati, OH: HOW Books, 2010), 2.

6. Saksham Kapoor, "Why Going Corporate Doesn't Mean Going Rogue: The Rise of Intrapreneurship," Startup 88, January 17, 2015, http://startup88.com/opinion/2015/01/17/going-corporate-doesnt-mean-going-rogue-rise-intrapreneurship/13801.

7. Kathryn Tuggle, "5 Steps to Selling an Idea to Your Boss," The Street, October 2, 2013, http://www.thestreet.com/story/12055474/l/5-steps-toselling-an-idea-to-your-boss.html.

8. Alexandra Levit, They Don't Teach Corporate in College: A Twenty-Something's Guide to the Business World, 3rd ed. (Pompton Plains, NY: Career Press, 2014), 100-1.

9. Prezi, https://prezi.com/; Google Slides, https://www.google.com/slides/about/.

10. Kawasaki, The Art of the Start, 48-50.

11. Gifford Pinchot, "Getting the Resources You Need: The Way of the Intrapreneurial Warrior," The Pinchot Perspective, March 29, 2013, http://www.pinchot.com/2013/03/getting-the-resources-you-need-the-way-ofthe-intrapreneurial-warrior.html.

12. Ibid.

13. Jerome A. Katz and Richard P. Green II, Entrepreneurial Small Business, 4th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), 216.

14. Ibid.

15. Kawasaki, The Art of the Start, 68.

16. Sylvia D. Hall-Ellis et al., Librarian's Handbook for Seeking, Writing, and Managing Grants (Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited, 2011), xv.