CHAPTER 2

ETHNIC TRIBAL DIVERSITY OF EASTERN GHATS AND ADJACENT DECCAN REGION

BIR BAHADUR,1 RAZIA SULTANA,2 K. V. KRISHNAMURTHY,3 and S. JOHN ADAMS4

1Department of Botany, Kakatiya University, Warangal–506009, India

2EPTRI, Gachibowli, Hyderabad–500032, India

3Department of Plant Science, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli–620024, India

4Department of Pharmacognosy, R&D, The Himalaya Drug Company, Makali, Bangalore, India

CONTENTS

2.1Origin of Ethnic Tribal Diversity

ABSTRACT

This chapter deals with the ethnic diversity of Eastern Ghats and the adjacent Deccan region. Emphasis is laid on the major ethnic tribes of Odisha, Undivided Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka. Ethnic tribal communities form a fairly a dominant percentage of the population of this area. These communities are the sources and holders of great knowledge on plants of cultural, social and utilitarian value. Not only the evolutionary origin of these ethnic communities, but also their social and cultural life are dealt with.

2.1ORIGIN OF ETHNIC TRIBAL DIVERSITY

The term “tribe” means a group of people that have lived at a particular place from time immemorial. Anthropologically the tribe is a system of social organization which includes several local groups on lineage and normally includes a common territory, a common language and a common culture, a common name, political system, simple economy, religion and belief, primitive law and own knowledge system. India is culturally, linguistically religiously and ethnically a very diverse country. Hence, “Tribals” are found in almost all the States of India. Tribals constitute 8.14% of the total population of India, numbering 84.51 million (as per 2001 census) and cover about 15% of the country’s area. Currently about 540 scheduled tribal communities exist. In terms of geographical distribution about 55% of tribals live in Central India, 28% in west, 12% in north-east India, 4% in South India and 1% elsewhere. These communities are actively working to preserve their rich cultures through broad institutional efforts. The strength of these communities varies from 31 people of Jarwa tribe to over 7 million Gonds. Thus, the Gonds form a very big tribal community, whereas the small communities comprising less than 1000 people include the Andamanese, Onge, Oraon, Munda, Mina, Khond and Saora. India is one among the top few countries with respect to its ethnic diversity (Singh, 1993; Vinod Kumar, 2002). Besides the ancient tribal communities, there is great ethnic diversity even among the mainstream people of India. It is derived from both the ANI and ASI populations (see later in this section for details). Although Hindus constitute the majority, there are also Muslims, Christians, Jains, Buddhists and Parsis. While ancient tribals invariably occupy forested and hilly tracts, the mainstream people occupy plains of India.

It is now more or less clear that the modern human species (Homo sapiens) originated in East African near Ethiopia around 200,000 years ago. It is also now known that the modern humans must have lived in Africa twice as long as anywhere else in the world. These details were evident from a study of mitochondrial genome (mt DNA) of females and Y chromosome of males of diverse primitive ethnic tribes of the world. As in the case of the origin of modern human species, its spread to different parts of the world is also deciphered by a study of mt DNA and Y chromosome. The earliest known mutation, which is found in all non-Africans, that helps to detect the human spread outside Africa is M168 in Y chromosome. This mutation had happened around 70,000 to 50,000 years ago (see Carney and Rosomoff, 2009). This mutation was followed by M9, which is common in all Eurasians and which first appeared in Middle East/Central Asia around 40,000 years ago. This was followed by M3 mutation, which arose in all Asian human populations that reached the Americas around 15,000 to 10,000 years ago. What made them to migrate out of Africa when they did so is still an unresolved mystery, although a few hypotheses have put forward (Scholz et al., 2007)

Which route did the modern humans take when they migrated out of Africa? Two paths lay open to Asia: (i) the path that led up the Nile valley, across the Sinai Peninsula and north into the Levant in Middle East. However, genetic data do not support this migration route; and (ii) from the horn of Africa via the mouth of Red Sea into Arabia and from there to central Asia, particularly Kazakhstan. From Kazakhstan humans got spread to other parts of Asia, Europe and Australia. Once in Asia, genetic evidence suggests that the population got split, one moving to Middle East, second to Europe, third to South East Asia and China (eventually reaching Siberia and Japan) and the last to Australia via India. Genetic data also indicate that humans in north Asia migrated eventually to Americas.

Migration of modern human species into India is the most complicated and discussed aspect of human spread. It is a well-known fact that India is remarkable for its rich ethnic diversity, as also for its plant (and animal) diversity. The ethnic diversity is due to India’s geographical position at the tri-junction of African, the north Eurasian and the Oriental realms, as well as due to its great variety of environmental regimes. India’s biological wealth has been attracting humans in many streams, at different times and from diverse directions of the old world. This had resulted in bringing together a great diversity of human genes as well as human cultures. This had also resulted in the mixing up between different ethnic groups. Hence, it is vital to focus on early human migrations into India in order to correctly understand the present day ethnic diversity that is seen in any region of the Indian subcontinent.

Gadgil et al. (1996) have made a fairly detailed discussion on the major migrations of humans into India. They speak of four major migrations: (i) the Austric language speakers soon after 65,000 years before the present (BP), probably from the north east; (iv) the Dravidian speakers in several waves after 46,000 years BP; (iii) the Indo-European speakers in several waves after 6,000 years BP; and (iv) the Sino-Tibetan speakers in several waves after 6,000 years BP.

Fairly recently, Thangaraj and his co-workers (see detailed literature in Thangaraj, 2011) have analyzed nearly 16,000 individuals from different ethnic populations of India (including several tribes) with genetic evolutionary markers (medinas and Y chromosome) to understand the genetic origins and structure of the ethnic Indian populations. In another genetic study the same group screened 560,123 SNPs across the genomes of 132 individuals belonging to 25 diverse groups from 14 Indian States (including Andaman) and six language groups. From these studies it was concluded by them that relatively small groups of ancestors founded most Indian groups, which then remained largely isolated from one another with limited cross-gene flows for long periods of time, perhaps 45,000 years BP. They have identified two main ancestral groups in India: (i) an “Ancestral North Indian (ANI),” and (iii) an “Ancient South Indian (ASI).” The first one is directly related to the Middle East, central Asia and Europe, while the second one is fairly indigenous (either not related to groups outside India or had some connection which is not yet established). Based on their studies, these authors have suggested three early major migrations from Africa to India: (i) via sea to Andaman; (ii) via land to South India through west coast (ASI population); and (iii) via land to North India (ANI population). From both ANI and ASI populations, the remaining parts of India were then populated.

2.2ETHNODIVERISTY

Nearly one tenth of the total population of India lives in Eastern Ghats. According to Chauhan (1998) and Ratna Kumari et al. (2007) 54 tribal communities (nearly 34% of the total population of Eastern Ghats region) occur in Eastern Ghats but according to another estimate there are 62 tribal communities (Swain and Razia Sultana, 2009). In the northern Eastern Ghats alone (Odisha and undivided northern Andhra Pradesh north of Godavari river) 54 tribal communities with about 60,00,000 people have been reported (see Krishnamurthy et al., 2014). According to other estimates there are 63 ethnic communities in Odisha State alone, of which several live in the Eastern Ghats region (Merlin Franco et al., 2004; Sandhibigraha et al., 2007). There are 33 tribes (27 according to Pullaiah, 2001) in the undivided state of Andhra Pradesh with a population of 42 lakhs (Sastry, 2002). Of these 33 tribals, 27 inhabit Eastern Ghats (Ratna Kumari et al., 2007). Some of these tribes are common to Odisha and northern Tamil Nadu. There are 36 tribal communities in Tamil Nadu of which about 10 communities are associated with E. Ghats and adjacent regions. There are five tribals communities that are associated with the E. Ghats of Karnataka. Thus, there is no uniformity in past reports with reference to the number of ethnic communities in Eastern Ghats and the adjacent region and the problem is at least partly due to the fact that some tribes are known by more than one name in different parts of this study region. Most, if not all, traditional ethnic communities of the Deccan region are the earliest inhabitants and autochthonous people of the forest tracts. It is needless to emphasize here that all the ethnobotanical knowledge of this study region are the result of the contributions of these various ethnic tribals groups due to their long interaction with nature. The tribals use a variety of plant species in their daily life and are well-versed with knowledge of edible greens, vegetables, fruits, seeds, medicines and other materials.

This section deals with the most important tribals communities of E. Ghats and the adjacent Deccan region. A detailed list of ethnic tribals associated with E. Ghats is given in Krishnamurthy et al. (2014).

2.2.1TRIBALS OF ODISHA

Odisha accounts for 3.47% population of India with a population density of 269 as against the national 342 per km2. Tribals form a major share of Odisha population, have many sociocultural similarities and together they characterize the notion of tribalism. Although as many as 75 tribals have been reported 11 are the most important. Some of these are described here.

2.2.1.1GONDS

Gonds or Gondi people are a Dravidian people of Central India, spread over the states of Madhya Pradesh, Eastern Maharashtra (Vidarbha), Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh, Telangana and Odisha. With over seven million people, they are the largest tribe in Central India. They are also the most important tribe of Odisha. They are a designated Scheduled Tribe. The Gonds are also known as Raj Gonds. The term “Raj Gond” was widely used in 1950s, but has now become almost obsolete, probably because of the political eclipse of the Gond Rajas. The Gondi language is related to Telugu and other Dravidian languages. About half of Gonds speak Gondi language or ‘kui’ language while the rest speak Indo-Aryan languages including Hindi. According to the 1971 census, their population was 51.54 lakhs (5,154,000). By the 1991 census this had increased to 93.19 lakhs (9,319,000) and by 2001 census this was nearly 110 lakhs.

The Pardhan Gonds are a clan of the large Gond tribe inhabiting Central India. They traditionally served the larger tribal community as musicians, bardic priests and keepers of genealogies and sacred myths. With declining support for their traditional role, the Pardhan Gonds have adapted to making auspicious designs on the walls and floors of mud huts, acrylic paintings on canvas, pen and ink drawings, silkscreen prints and large-scale murals. Traditionally the Gondi people had a social institution (school) known as Ghotul, a kind of mixed dormitory system for the unmarried youth, which was the main means of education and introduction to adult life.

Gonds go out for collective hunts and eat fruits and roots they collect. They usually cook food with oil extracted from sal and mahua seeds. They also use medicinal plants. These practices make them mainly dependent on forest resources for their survival. Their religion is animistic, and their pantheon of gods includes 83 gods. Kandhamal district in Odisha has a 55% Gond population, and was named after a subtribe.

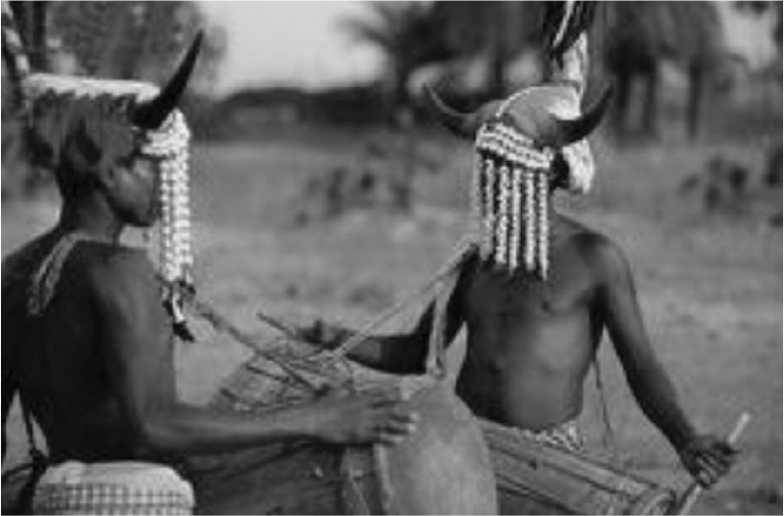

Dongria Gonds inhabit the steep slopes of the Niyamgiri Range of Koraput district and over the border into Kalahandi and work entirely on the steep slopes for their livelihood. The Niyamgiri Range provides a wealth of perennial springs and streams, which greatly enrich Dongria cultivation. Gonds also occupy northern parts of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh (Figure 2.1).

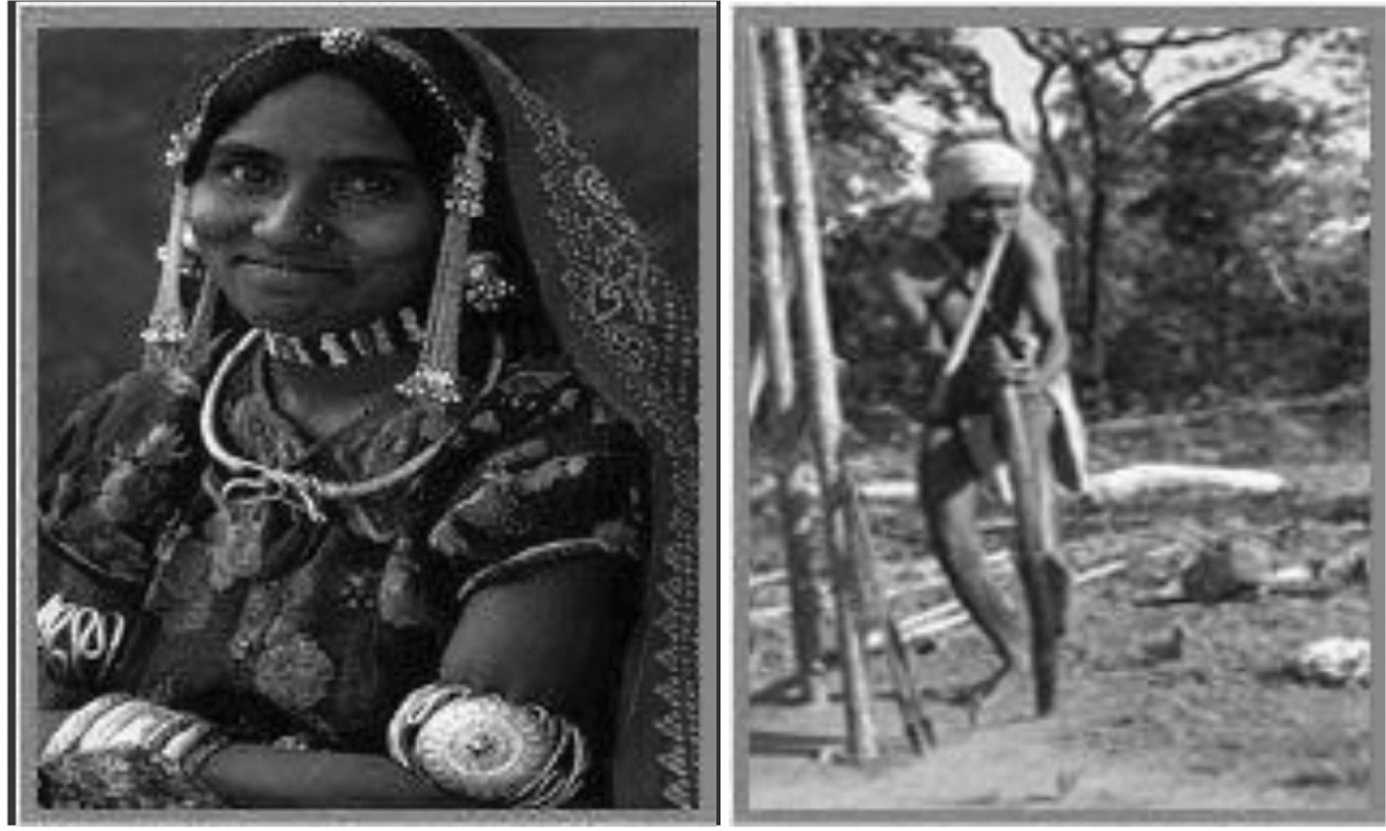

FIGURE 2.1Two Gond Women.

2.2.1.2SAVARAS

The Savaras are found inhabiting the Eastern Ghats of Odisha and undivided Andhra Pradesh. Their population is 1,05,465 (1991 census). The total literacy rate among Savara is 13.68. They build their settlements on hill slopes and near hill streams to facilitate easy access to terrace fields, and for fetching water. The most significant feature of the social organization of the Savaras is the absence of clan organization. For all practical social purposes, such as marriage, the group having a common surname is exogamous.

2.2.1.3BHILS

Bhils or Bheels are primarily an aborigine Adivasi people of Central India, particularly of Odisha. They speak the Bhil languages, a subgroup of the Western Zone of the Indo-Aryan languages (Figure 2.2).

FIGURE 2.2Bhils tribe.

(Source: http://tribes-of-india.blogspot.in/2008/09/bhils-tribes-of-india.html)

Bhils are divided into a number of endogamous territorial divisions, which in turn have a number of clans and lineages. The Ghoomar dance is one well-known aspect of Bhil culture.

2.2.1.4BAGATA

The Bagata tribe is regarded to be one of the aboriginal tribes of India. Tribal communities reside in different parts of Odisha and in Northern Andhra Pradesh. Festivals, dance as well as musical bonanza make the culture of these Bagata tribes quite exquisite. Special mention must be made about the Dhimsa dance that has been practiced in the Bagata tribal society. It is a dance form where Bagata tribes of all ages participate quite energetically.

2.2.1.5MUNDA

Munda tribe mainly inhabits Odisha. Hunting is the main occupation of the Munda tribe. Originally they were living in core forest areas of Odisha but now have been pushed to buffer zones (Figure 2.3).

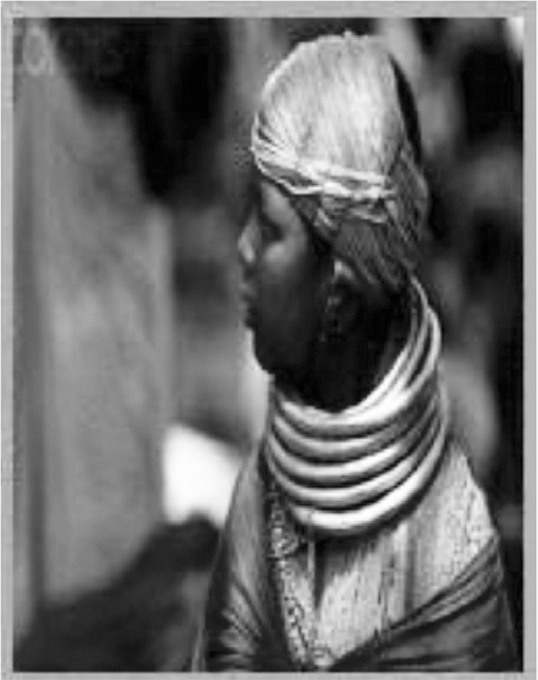

FIGURE 2.3Munda tribal woman.

(Source: http://tribes-of-india.blogspot.in/2008/10/munda-tribes-of-india.html)

2.2.1.6SANTHAL

The Santhal tribe is the third largest tribes in India. Belonging to pre-Aryan period, and have been the great fighters, this tribe is found, Odisha, Santhal Tribe take pride in their past. Santhali is the prime language spoken by the Santhal tribe. This tribe also has a script of its own called Olchiki. Apart from Santhali they also speak Bengali, Oriya and Hindi.

2.2.1.7GADABA

The Gabada tribe is one of the oldest and jovial tribes in India and are located in the southern fringes of the Koraput district. Gadabas are very friendly and hospitable. Their villages are with square or circular houses and conical roofs. The women are well-dressed and are fond of wearing ornaments generally made out of brass or aluminum.

2.2.1.8JATAYA

Jataya tribe of Odisha is named after the mythological figure Jatayu of Ramayana epic.

2.2.2TRIBALS OF UNDIVIDED ANDHRA PRADESH

Nearly 70% of the total population of undivided Andhra Pradesh lives in rural and forested areas. More than 35 ethnic tribes have been reported and the most important are discussed in the following subsections.

2.2.2.1SAMANTHAS

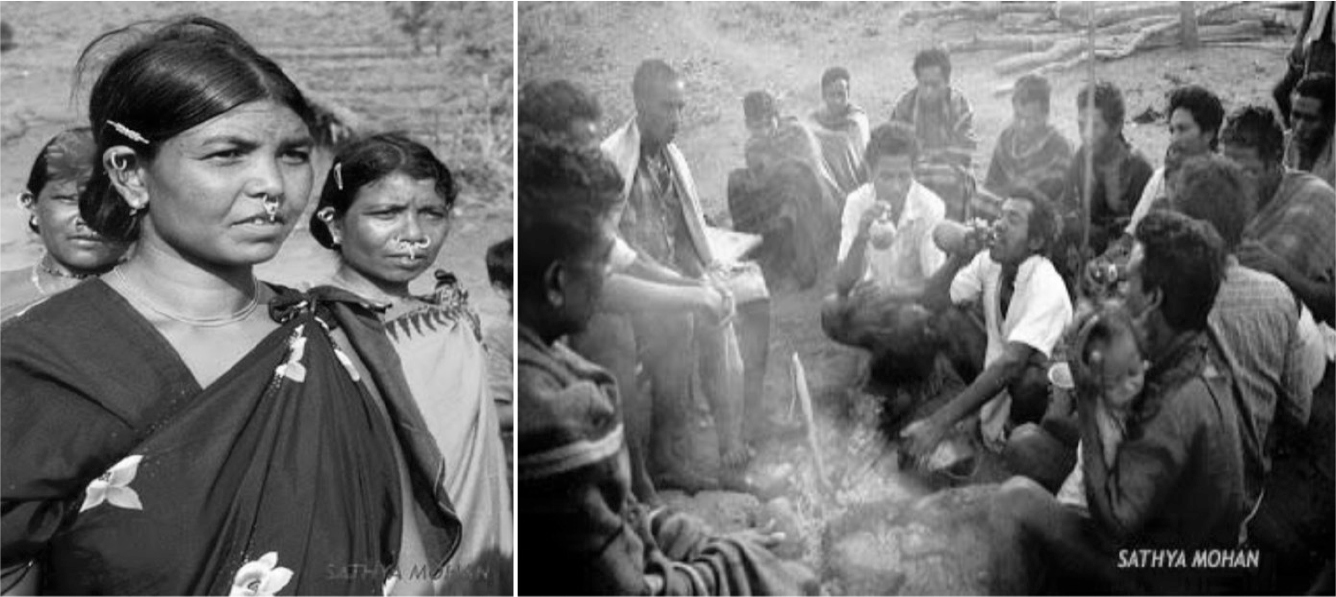

The Samanthas of Visakhapatnam agency are one of the few traditional agricultural communities living in the Eastern Ghats of Andhra Pradesh and Odisha (Sathya Mohan, 2006). They speak “Kuvi,” a language which is a brand of Telugu language. Samanthas clear the jungle on hill slopes, burn the trees and grow the crops in the ashes. Podu—the Slash and burn cultivation—is the major livelihood for these tribals. They used to cultivate a plot for six or seven years and leave the land fallow for about 10 years, by shifting their cultivation to another hill slope thus enabling the soil fertility of the old plot. Now-a-days, the fallow period is reduced to two or three years. The podu cultivation is simple and uses only hoe and human labor. Though the crop output is poor and not profitable, slash and burn cultivation is meant for their own survival. The remarkable feature of podu cultivation is that many varieties of cereals and vegetables can be grown in one plot (Figure 2.4).

FIGURE 2.4(a) Samantha women; (b) Samantha community enjoying festivities through drinking, and smoking (Sathya Mohan, 2006; used with permission from ENVIS Division of EPTRI).

The Samanthas have a strong sense of community living. Each and every activity of the village including festivals is carried out by all the families working in close co-operation with each other and every household contributes for it. Slash and burn cultivation is initiated with a religious ritual. In February, during the seed festival known as “Biccha Parbu,” the Samanthas worship the village Goddess “Jakiri Penu” by offering animal sacrifices. The Samanthas believe that sowing seeds mixed with the sacrificial blood will impress the fertile powers of Nature. They mainly grow dry paddy, ragi (Eleusine coracana), sama and oliselu (Guizotia abyssinica) in these fields.

Every family also cultivates kitchen garden crops like chillies, tobacco and vegetables in a small piece of land near their hamlets. Women and children collect minor forest produce of various types, such as edible and herbal roots, tubers and creepers, leaves and fruits. The Samanthas sell most of these products at the weekly shandies and buy commodities like kerosene, oil, salt, ornaments and clothing. Traditionally, the shandies have provided the people with an opportunity to barter their surplus produce. The distribution system earlier was limited to the tribal communities in the shandies of this area. But today, these market places have become the centers for commercial exploitation of the tribals by the traders from the plains.

Their economic activity is interdependent with their religious life, which consists of various Gods and Goddesses, who are symbols of various forces of Nature. They believe in absolute surrender of human spirits to the Natural forces. The availability of food in the jungle, the fertility of the Mother Earth, the rainfall and also the outbreak of epidemics are supposed to be dependent on the mercy /wrath of the respective Gods and Goddesses. In the event of an epidemic the Samanthas propitiate the Goddess of the disease known as “Ruga Penu”. After worshipping they ceremonially send the Goddess out of the village. The religious sense of archaic oneness with Nature has characterized the many generations of traditional life among the Samanthas.

2.2.2.2KOYAS

The Koyas are one of the few multi-lingual and multi-racial tribal communities (Sathya Mohan, 2006). They are also one of the major peasant tribes of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana numbering about 3.60 lakhs in 1981. Physically they are classified as Australoid. The Koyas call themselves “Koithur.” The lands of Koithur includes those near the Indravati, Godavari, Sabari, Sileru rivers and the thickly wooded Eastern Ghats, covering parts of Bastar, Koraput, Warangal, Khammam, Karimnagar and the East and West Godavari districts. Most Koyas speak the Koyi language which a blend of Telugu (Figure 2.5).

FIGURE 2.5Koya men with traditional head gear.

(Source: http://www.storypick.com/27-beautiful-photos-from-different-ethnic-tribes-of-india/)

The story of the Koyas dates back to pre-historic times. They seem to have had a highly evolved civilization in the past in which they were a ruling Tribe. According to the Koya mythology, life originated from water. The friction between the fourteen seas resulted in the emergence of moss, toads, fish and saints. The last saint was God and He first created Tuniki (Diospyros melanoxylon) and Regu (Ziziphus mauritiana) fruits. During the 18th century, the Marathas invaded and subverted the Koyas along with the Gonds. The continuous pillage and harassment by the non-tribals resulted in the loss of the vestige of Koya civilization. The Koyas were driven to take refuge in the inaccessible highlands. In this period they were depicted by travelers as treacherous savages.

There are many endogamous sub-divisions among the Koyas of Bhadrachalam agency, such as Racha Koya, Lingadari Koya, Kammara Koya and Arithi Koya. Each group is vocationally specialized having a separate judiciary system, which ensures group endogamy. There are also differences in food habits. Lingadari Koyas do not eat beef and do not interdine with others. They perform purificatory rites to depollute the effects of inter group marriages. The Racha Koyas are village administrators. They also perform rituals during festivals. Kammara Koyas make agricultural implements. They are blacksmiths and are generally paid in kind. Arithi Koyas are bards. They narrate the lineages. They are the oral custodians of Koya mythology. Each of these sub-divisions among the Koyas has exogamous phratries having separate totems, which are again split into a number of totemistic sects, which form the lineage (“velpu”) pattern. For example, in Chinthur mandal of Bhadrachalam agency, the Paderu Gatta (phratry) of Racha Koyas worship “Dhoolraj” and their totem is wood. These phratries have a number of totemistic sects each denoted by a name, totem and worshipped by a group of families having separate names. For instance, Gatta worshippers of Bheemraj are further classified into three groups on the basis of their “Ilavelpulu” (family deities).

The Koyas have a patrilineal and patrilocal family called “Kutum.” The nuclear family is the predominant type. Usually, sons in a family live separately after marriage, but continue to do joint cultivation (Pottu Vyavasayam) along with parents and unmarried brothers. Monogamy is prevalent among the Koyas. The preferential marriage rules favor mother’s brother’s daughter or the father’s sister’s daughter. Generally, the mate is selected through negotiations. But other practices of capture and elopement also exist, involving a simple ritual of pouring water on the girl – the water being the symbol of fertility. There is bride price involved in arranged marriages. Marriage is celebrated for three days. It is not simply an affair between two families. It is an occasion for two villages and all the relatives. Every person carries grain and liquor to a marriage to help the bridgroom’s family. Marriages take place in summer when palm juice is abundantly available. The Bison-horn dance is a special feature on the occasion of a marriage ceremony among the Koyas. Birth, marriage and death are the three important aspects of life and each event is celebrated on a grand scale in Koya society. The funeral ceremony among the Koyas is strikingly peculiar. The corpse is carried on a cot accompanied by the kinsmen and villagers including women. They symbolically offer material objects like grains, liquor, new clothes, money and a cow’s tail by placing them on a cot besides the corpse and the whole cot is placed on the pyre with the feet towards the west. They generally burn the corpse. The corpses of pregnant women and children below five months old are buried. They have a ceremony on the eleventh day after the death, which is called “Dinalu.” At this time they believe that the spirit of the dead comes back and resides in the earthen pot called “Aanakunda.” The occasion of death is a common concern in which all the relatives share the burden and expenditure of the family of the deceased. After the ceremony is over, they sing, dance and have a feast.

The major forest species exploited by Koyas are teak, bamboo, maddi (Terminalia alata) and cashew. The minor forest produce includes beedi leaves (Diospyros melanoxylon), gum, honey and tamarind. Sorghum is the staple crop and rice and tobacco are grown along the river banks.

There are 89 Koya villages and a small town in Chintur mandal with a population density of 123 persons per sq.km. Agriculture is totally dependent on rains. Owing to small land holdings (the average land-holding per family is 2.0 acres wet and 4.1 acres dry land) and no irrigation facilities, about 55% of the families continue practicing slash and burn (podu) cultivation, while 10% of the population is landless. Due to the limited availability of land for cultivation, total dependence on rain for irrigation and the growing population pressure over the Koyaland, the agriculture activity of the Koyas has become predominantly a subsistence way of farming. The ecological surroundings – especially forests – provide the Koyas with food, beverages, fodder, shelter and medicinal herbs.

Though the Koyas are farmers by occupation, most of their food supplies are drawn from the forest. Roots and fruits form their subsidiary food. They eat Keski dumpa and Karsi dumpa, which are the common roots available in this region. They cut these roots into pieces, keep them in running water for three days and boil them to make them edible. During drought years the Koyas go in groups into the forest to collect these roots in large quantities. Their staple diet is sorghum. They grow several varieties of sorghum (Konda jonna, Pacha jonna, etc.) and a few pulses. Rice is also grown in a few wetlands.

The Koyas also collect various forest products to supplement their meager agricultural returns. They sell these products in the weekly shandy and buy other required commodities. There is no other monetary transaction among the Koyas except in the shandy. On the whole only 0.4% of the agricultural produce is sold.

Joint cultivation, known as “Pottu Vyavasayam” is a common practice among the Koyas. Landless families go with their agricultural implements and join those who own land. The yield is shared between the landowner and others who have contributed labor. This practice ensures unity within the group and avoids further division of land holdings.

The Koyas are expert hunters and the good hunters are looked upon as heroes. For the Koyas, hunting is an essential skill for food as well as for defense from wild animals in the forest. On the occasion of the “Vijja Pandum” (the festival of seeds), Koyas go hunting in groups. Fish is another important food for the Koyas. In villages near rivers, quite often fish is a meal for every family. They ensure fair share of fish to all. The Koyas use various types of nets tied to bamboo poles, which are used in still waters.

During the toddy palm season, every Koya family lives mainly on palm juice for almost four months. For them palm juice is not just a beverage, but also a complete food. On an average, every Koya family owns at least four to eight palm trees. Palm juice is consumed three to four times a day in large community gatherings known as “gujjadis.” The Koyas consider the palm tree as a gift of nature and to secure this gift they worship the village Goddess “Muthyalamma.” On all social and religious occasion, liquor plays an important role among the Koyas. The “Ippa Sara” or the mohuva drink (Madhuca longifolia) is purely an intoxicating beverage. The Koyas consume mohuva liquor to get relief from the physical hardship of the day and to withstand extreme variations in the climate.

The houses are built within one’s own agricultural land. These are rectangular and are built of the material that is available from the forest. These houses are constructed on an elevation of two to three feet with walls made of bamboo, plastered with mud and roofed with palm leaves. They are leak-proof, quite warm during winter and cool during summer. Most of their festivals are related to agricultural operations. Kolupu is one such occasion, which comes during November. The Koyas worship the Earth-Goddess “Bhudevi” and they enlist the co-operation of the Goddess by offering animal sacrifices during the festival. They believe that sowing seeds that are soaked in sacrificial blood brings them good crops. The Koyas deify their ancestors and worship them on all social occasions. The entire clan members join together to worship their ancestors. The Koyas believe in four guardian deities who are supposed to control the four directions. The Koya pantheon consists of various gods and goddesses who are the symbols of various forces. Among them Bhima, Muthyalamma, Sammakka and Sarakka are worshipped by non-tribals of the surrounding regions as well. The sense of supernaturalism is strongly rooted in the Koya’s concept of nature. They worship personal spirits, which are thought to animate nature. They also believe in evil spirits that are dangerous to the harmony of group life. The traditional medicine man “Buggivadde” and the sorcerer “Vejji” are supposed to ward off all kinds of evil spirits. The Koyas celebrate festivals indicating the onset of particular seasons for tapping palm juice, collecting mohuva flowers, beginning agricultural operations, hunting and fishing. Every koya village is a socio-political unit and also a part of a larger social and territorial unit called “Mutha,” a cluster of villages linked by economic, political and kinship ties. The customary law of the Koyas ensures communal ownership of natural resources administered by the village headman known as “Pedda.” The pedda is the senior-most person who first settled in the village and established the village Goddess. This position is held by descendents of the same family. Pedda controls the social, political and religious activities in the village. The village panchayat consists of the other members (Pina pedda, Vepari, Pujari, etc.) who deal with minor problems. Sometimes the pedda holds two or three positions in a panchayat. The village panchayat is the final authority over all issues in a village. The overall judicial system of a cluster of villages is maintained by the “Samithi Poyee,” a judicial head who is assisted by the people known as “Veparis.” Issues are dealt with in co-operation with the village panchayat and this makes every village a part of a wider cluster known as mutha and is held by tribal norms.

2.2.2.3BANJARA

The Banjara are a class of nomadic people from the Indian State of Rajasthan, now spread all over Indian sub-continent. They claim themselves to have descended from Rajputs, and are also known as Lakha Banjara means Lakhapati, Banjari, Pindari, Bangala, Banjori, Banjuri, Brinjari, Lamani, Lamadi, Lambani, Labhani, Lambara, Lavani, Lemadi, Lumadale, Labhani Muka, Goola, Gurmarti, Dhadi, Gormati, Kora, Sugali, Sukali, Tanda, Vanjari, Vanzara, and Wanji. According to J.J Roy Burman’s book titled, “Ethnography of a Denotified Tribe the Laman Banjara,” the name Laman is popular long before the name Banjara and the Laman Banjaras originally came from Afghanistan before settling in Rajasthan and other parts of India. According to Motiraj Rethod also, the Lamans originally hailed from Afghanistan. Together with the Domba, they are sometimes called the “gypsies of India”. They are known for colored dress, folk ornaments and bangles. The Lambadas are one of the largest tribes in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana and live in exclusive settlements of their own called Tandas, usually away from the main village. They tenaciously maintain their cultural and ethnic identity. The Lambadas believe that the world is protected by a multitude of spirits benign and malign. Hence the malignant spirits are periodically appeased through sacrifice and supplication called Tanda.

Banjara people celebrate Teej festival in a grand scale. The festival, which is celebrated during Shravan in the month of August, is considered as a festival of unmarried girls who pray for better grooms. Girls sow seeds in bamboo bowls and water them three times a day, for nine days and if the sprouts grow thick and high, it is considered as good omen for a better future groom. The bowls with seedlings are kept in a prominent place and girls sing and dance circling the bowl.

Folk art of Banjara people includes Dance, Rangoli, Embroidery, Tattooing, Music and Painting, of which embroidery and tattooing have special significance in the community. Lambani women specialize in preparing lepo embroidery on clothes by interweaving glass pieces in colorful clothes. The craft known as Sandur Lambani Craft made by Lambani people has got Registered Geographic Indication tag in India, enabling the community people to exclusively market them in that name.

Banjara people are generally classified as Hindus. They worship Hindu gods like Krishna, Balaji, Jagadamba Devi, Hanuman, etc. They also worship Sati Aayi, Seva Bhayya (or Sevalal), Mithu Bhukhiya, Banjara Devi, etc., which are specific to the community. Banjara Devi is located usually in forests in the form of a heap of stones. Mithu Bhukhiya was known as an expert dacoit of the tribe and the community pays high respect to him who is worshipped in a hut built in front of Tanda or village with a white flag on top. Nobody sleeps in the special hut built for Mithu Bhukhiya. Seva Bhaya or Seva Lal is another historic person who draws high respect from Banjara people. He became a saint and protector of women of the community. They speak Banjari language, also called Goar-boli, which belongs to Indo-Aryan group of languages and the language has no script. In India, Banjara people were transporters of goods from one place to other and the goods they transported included salt, grains, firewood and cattle.

2.2.2.4KONDA REDDY

Konda Reddy is a community that prefers to remain unmarried than to stir out of its habitation mostly in Khammam, Telangana. They are concentrated in Pusukunta. They preferred to live in hills for decades by stonewalling the influence emanating from the civilized plains. Living far from the maddening crowd, the clan is still primitive. Apprehensive of losing their rights over minor forest produce, which is their source of livelihood, they turned down the offer of land and pucca houses as part of the rehabilitation programmers. The ‘Konda Reddy’ tribe is against exchanging Pusukunta for any kind of marriage proposal.

2.2.2.5VALMIKI

It is a Dalit sect of Hinduism centered on the sage Valmiki. The community is found in Punjab, Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Gujarat and Punjab, Rajasthan (Figure 2.6).

They worship Valmiki as their ancestor and God. They consider his works, the Ramayana and the Yoga Vasistha, as their holy scripture. In the state of Andhra Pradesh, Valmikis are referred to as Boyas. The titles of the Boyas are said to be Naidu (or Nayudu), Naik, Dora, Dorabidda (children of chieftains), and Valmiki.

2.2.2.6KONDA DORA

Visakhapatnam district of Andhra Pradesh is known for Konda Dora tribe. Konda Dora tribe is divided into a number of clans, such as Korra, Killo, Swabi, Ontalu, Kimud, Pangi, Paralek, Mandelek, Bidaka, Somelunger, Surrek, Goolorigune, Olijukula, etc., Konda Dora are very dominant in the district. These tribal communities are considered to be forest dwellers living in harmony with their environment. They depend heavily on plants and plant products for making food, forage, fire, beverages and drinks, dye stuff and coloring matters, edible and non-edible oils, construction of dwellings, making household implements, in religious ceremonies, magico-religious rituals, etc. A close association with nature has enabled these tribal people to observe and scrutinize the rich flora and fauna around them for developing their own traditional knowledge and over the years, they have developed a great deal of knowledge on the use of plants and plant products as herbal remedies for various ailments.

2.2.2.7CHENCHUS

The Chenchus are a designated and conservative Scheduled Tribe community found in the Indian States of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Northern Karnataka and Odisha but predominantly undivided Andhra Pradesh. They are an aboriginal tribe whose traditional way of life is based on hunting and gathering, particularly in the Nallamalai forests or Andhra Pradesh. The Chenchus speak the Chenchu language, a member of the Telugu branch of the Dravidian language family. Some Chenchus have specialized in collecting forest products for sale to non-tribal people. Many Chenchus live in the dense Nallamala forest of Andhra Pradesh for hundreds of years.

The Chenchus are unfazed by their natural surroundings. The bow and arrow and a small knife is all the Chenchus possess to hunt and live. The slender build of their bodies is deceptive and express little of their strong and resilient nature.

The dark-complexioned Chenchus are one of the primitive tribal groups that are dependent on forests and do not cultivate land but hunt with bow and arrow for a living. The Chenchus have responded rather unenthusiastically to government efforts to induce them to take up farming themselves. They prefer to live in the enclosed space and geography leading a life of an unbroken continuity (Sathya Mohan, 2006). Their meal is simple and usually consists of gruel made from jowar or maize, and boiled or cooked jungle tubers. The Chenchus collect jungle products like roots, fruits, tubers, beedi leaf, mohua flower, honey, gum, tamarind and green leaf and sell them. They have hardly developed any technique for preserving their food. The Chenchu village is known as ‘penta’ with a few huts scattered here and there. The village elder is the authority. The Chenchus are a broad exogamous group and are basically Hindus. The marriage ceremony is performed with traditional rituals in front of the community and the priest or Kularaju officiated over the marriage rites. The Chenchus have a strong belief system and worship their deities like Lingamayya, Maissamma/Peddamma, Particularly during July/August. Their celebrations are austere, serene, simple and sometimes can be wild, intoxicating and mystical.

2.2.2.8MALIS

Tribes are predominantly found in tribal areas of Visakhapatnam, Vizianagaram and Srikakulam districts. They are also called Mahali and Malli. Their population according to 1991 census is 2925. The total literacy rate among Mali is 17.47. The traditional dormitories, known as ‘Kuppus’ were once popular in this community. Marriage by negotiations, marriage by mutual love and elopement, marriage by service are different ways of acquiring mates.

2.2.2.9KOTIA

Kotia is chiefly found in the tribal areas of Visakhapatnam district of Andhra Pradesh and adjoining Odisha; their population as per 1991 census is 41,591 and their total literacy rate was 17.83. Four types of acquiring mates are in vogue in this community. They marry by negotiations, by mutual love and elopement, by capture and marriage by service. Divorce is permitted. Widow or widower re-marriages are permissible (Figure 2.7).

2.2.2.10.KOLAMS

Kolam tribe inhabits areas of Telangana (and Maharashtra). They mainly speak Kolami language, but are also fluent in Marathi, Telugu and Gondi languages. They follow Hindu based rituals and ceremonies. Agriculture and working in the forests are the occupations. Kolam tribe return barefoot after performing a pilgrimage. Drum or tappate and bamboo flute or vas are the musical instruments used in festive occasions.

2.2.2.11ANDH

The Andh are one of the tribes of India living in the hilly tracts of Adilabad in Telangana. They are further subdivided into the Vertali and the Khaltali. Marriage by negotiations is common among Andhs but marriage by intrusion is also prevalent. Widow remarriages are permitted among Andhs. Divorce is permitted. They mainly subsist on agriculture followed by agricultural labor. They partly subsist on collection of forest produce, hunting and fishing.

2.2.2.12YANADIS

Yanadis are one of the most primitive tribes and occupy the forest areas of East Godavari in Andhra Pradesh and a part of Khammam District in Telangana state. They occupy of the Godavari river in the forests. The Yanadis of Nallamalais are essentially hunters and foragers and their settlement patterns reflect this type of activity. Their huts are made of bamboos. They frequently migrate from one place to another when resources are exhausted, but this migration is only within a short radius. They use simple traps and snares and catch small rodents for their food (Parthasarathy, 2002).

2.2.2.13YERUKALA

The Yerukala tribe is considered as one among the 33 scheduled tribes of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana (India census 2006). It is a semi-nomadic tribe inhabiting the plains. The people of this tribe are traditionally basket makers and swine herders. Though live mostly in multi-caste villages, maintaining symbiotic relations with non-tribals, they cultivate their unique beliefs and practices. They are considered to be the native of Southern Andhra Pradesh but now largely occupy Telangana, particularly in Warangal district. The traditional healers of Yerukala ethnic community have been using around 30 plant species for various formulations to cure chronic disorders.

2.2.3TRIBALS OF KARNATAKA

A blend of culture, religion and ethnicity is represented by the tribes of Karnataka. More than 55 ethnic tribes have been reported. The most important tribes of Eastern Ghats of Karnataka State includes Bedar, Hakkipikki, Kadu kuruba, Kattunayakan, Konda kapus, Sholaga, etc. These tribes of Karnataka have built their settlements in several hilly and mountainous areas like Sandur, Chitradurga, Nandi and BR hills. As far as the languages are concerned, the tribes of Karnataka state converse with each other in different languages. Kananda language is the main language. Following the tradition of most of the tribes of the whole country, these tribes of Karnataka too have taken to diverse religions, although Hinduism is the most prevalent religion. Several other tribal communities of Karnataka possess their distinct tradition and ethnicity. They communicate in their local dialect and they also maintain their own tradition. Some of them are also reckoned as being originated from the warrior race.

The tribes of Karnataka are also known for their costumes, cultural habits, folk dances and songs, foods and their way of celebrating different festivals and occasions. A renowned dance format of the tribal communities of Karnataka is the open-air folk theater, better known as Bayalata. The theme of this dance drama centers around several mythological stories. This dance is executed at religious festivals and various social and family occasions. Generally these festivals start at night and carry on till quite a long period of time until day break.

The Bedar tribes belong to the Dravidian language family group. The Bedar tribal community can be found in several places of Karnataka. They are also known as Beda, Berad, Boya, Bendar, Berar, Burar, Ramoshi, Talwar, Byadar, and Valmiki. The word ‘bedar’ has an etymological significance and is derived from the word bed or bedaru, which signifies a fearless hunter. The ancestors of Bedar tribes may be the Pindaris or Tirole Kunbis. Within the Bedar tribal community, there are few Hindus and are called Bedar while the Muslims are referred to as Berad. The societal structure of the Bedar tribal community is quite significant. The Bedar tribe has six social groups. They have their indigenous customs and traditions. They eat meat and also drink liquor. Just like many of the tribal communities, the institution of marriage is given prime importance in Bedar tribal communities. The proposal of marriage usually comes from the parents of the bridegroom. Although child marriage is prevalent in the Bedar society, the bride does not reside with her husband till her puberty. Marriage within the subgroup of the Bedar community is not allowed. Widow re-marriage and divorce are permitted. In matters of administration, especially in case of disputable matters, the Bedar tribes take the help of the village headmen, popularly called Kattimani. Bedar tribal community has developed immense faith on various practices related to religion and spiritualism like fortune telling, magic and astrology.

Kadu Kuruba tribals of Karnataka live in forests as their name indicates. Cultural excellence is widely being depicted in all its aspects like dance, language, religion, festival, etc. by this community. Just like many of the tribal communities of Indian subcontinent, Kuruba tribes also are the ardent followers of Hinduism. To top of it, these kadu Kuruba tribes practice Halumatha, also known as palamatha by many people of the Indian Territory. The peculiar ritual of this Kadu Kuruba tribal community is that they revere ‘Almighty Source’ in a stone, which has been identified as Linga. According to the beliefs of these tribes, stone is the source for the soil, which in turn nourishes all the plants. Some anthropologist go to the extent of saying that the worship of stone as well as Shakti, in the form of deities like Yellamma, Renuka, Chowdamma, Kariyamma, Chamundi, Bhanashankari, Gullamma, etc. have originated from the tradition of Kadu Kuruba tribal community. However ancestral worship too has been incorporated in the religion of the Kadu Kuruba tribal community. Kadu Kuruba tribe is one of the significant tribes who have got the rich tradition of worshiping stone and also their predecessors with lots of festivity and enthusiasm. Apart from these tribal groups, the Kattunayakan tribe is said to be the descendants of the Pallavas. Collection of food is one of the chief professional activities of the Kattunayakan tribe.

Another important tribal group is the Sholaga tribe. Members of the scheduled Sholaga tribe converse with each other in the beautiful language of Sholaga. They are known by different names like Kadu Sholigau, Sholigar, Solaga, Soligar, Solanayakkans, Sholanayika. They follow of Hindu religion. They occupy the BR hills besides being present in Tamil Nadu’s Timban-Sathyamangalam hills. As per 1981 census their population was 4828. They worship Madeshwara, the god of hunting. They are non-vegetarians. They were originally described to sleep naked around a fire lying on a few plantain leaves and covering themselves with others. They live chiefly on the summits of mountains where tigers do not frequent. Their huts are made on bamboos. The sholaga society is divided into 12 exogamous, partrilineal clans called kulams which regulate their marriage system. They bury the dead. They are hunters and food gatherers and were earlier known to practice shifting cultivation (Parthasarathy, 2002). Sholaga tribe are scattered in different parts of Karnataka, such as Mysore and BR hills. Sholaga tribal community of Karnataka is basically settled in several parts of this state and has enriched the culture and heritage of this state with their own distinctness.

Quite a number of this Sholaga tribal community collects various products from the forest areas. That this Sholaga tribal community is very much pious and the people of this group are religious minded. Hinduism is the main religion. However, many of the members of this Sholaga tribal community have still retained the local practices and customs of this community.

Lingayat Mathpatis often act as their priests. Janai, Jokhai, Khandoba, Hanmappa, Ambabai, Jotiba, Khandoba are some of the supreme deities of the Bedar tribal community. Images from deities like Durgava, Maruti, Venkatesh, Yellamma and Mallikarjun are made from silver, copper or brass. Cultural exuberance of the whole of the Bedar tribal community has nicely being depicted in all its aspects like festivals, language, jewelries, etc. The people communicate in Bedar language. Both Bedar males and females are very fond of wearing ornaments that are made up mainly from silver and gold. In addition, Bedar females place their hair in loose knots, wear several other ornaments like nose-rings and a gold necklace. Moreover there are quite a handful of Bedar tribes who also shave their heads, according to the custom. Tattooing also is a special custom of these Bedars. Males and females of the Bedar tribe do tattooing on the several parts like forehead, corners of the eyes and forearms. Rites, rituals and customs are part of the Bedar community.

2.2.4TRIBALS OF TAMIL NADU

According to the 2001 census the tribal population of Tamil Nadu is 6,51,321. There are around 38 tribes and sub-tribes in Tamil Nadu. The tribal people are predominantly farmers and cultivators and most of them are much dependent on forest lands.

2.2.4.1KURUMBA

Kurumbas are jungle-dwellers. They are generally believed to be the descendants of the Pallavas. They have settled in scattered settlements. The tribe is divided into five groups. Shola Nayakkars, Mullu, Urali, Beta and Alu. They have flat noses, wedge-shaped faces, hollow cheeks and prominent cheekbones, slightly pointed chins, and dark complexion. The women wear a waist cloth and sometimes a square cloth that comes up to the knees. Ornaments play a major part in the costumes. They have their distinct culture, tradition, religious customs and social practices. Kurumbas are one of the backward tribes of Tamil Nadu with no accessibility to modern amenities. Many of them are illiterate. Many Kurumbas were known for their black magic and witchcraft in the past. They speak the distinctive Kurumba language. The Kurumba art uses four colors traditionally: red (from red soil), white (from both soil), black (from the bark of Karimaram), and green (from the leaves of Kattu Aavaarai).

The Uraly subtribe of Kurumba tribe Tamil Nadu is found only in the Eastern Ghats in the districts of Erode and Salem. Their population as per 1981 census was 9224. The term Uraly means a village person. According to Parthasarathy (2002) they occupy the low land region between Eastern Ghat peaks of Salem and Erode. They speak Kannada and Tamil. They are non-vegetarians although ragi is their staple food. The Uraly society is divided into seven exogamous class called Kulams (Kanar, Kodiyari, Ennayari, Onar, Thuriyar, Vethi and Vayanar). Married women wear a Thali around their neck. The society is patrilineal. They bury the dead and perform ancestral worship. They practiced shifting cultivation in the past but no longer do it now. For their living they collect fruits, trap wild animals and birds. Women are skilled at making fine mats and baskets out of reed and bamboo.

2.2.4.2IRULAS

Irulas are an important tribal community of Tamil Nadu and occupy Coimbatore, Erode and part of Nilgiri districts. Their total population is around 25,000. Nearby 100 Vettakad Irula settlements are found in forest areas and in the deep mountainous jungles. Traditionally Irulas main occupation has been snake and rat catching, but also work as laborers in agricultural fields during sowing and harvesting. They also are involved in fishing. This tribe produces honey, fruits, herbs, roots, gum, dyes, etc. and trades them with the people in the plains. They speak the Irula language, a member of the Dravidian family. The Irulas are related to the mainstream Tamils, Yerukalas and Sholagas.

2.2.4.3MALAYALIS

One of the most important and largest scheduled ethnic tribes of Tamil Nadu is the Malayali tribe. They occupy the Eastern Ghats hills of Tamil Nadu, such as Kolli, Shervaroys, Pacha malais, Kalrayans, Javad, Pudurnadu and Yelagiri. According to 1981 census the population of Malayalis was 2,09,040. They are Hindus. The tribes consists of cultivators, woodmen and shepherds and are not uncivilized. They migrated to hills in fairly recent times. They are believed to be Vellalars who have migrated to hills due either to Muslim rule or due to fearing for conversion to Vaishnavites. They speak the Tamil language. They are divided into two endogamous groups on the basis of their tattooing marks on their bodies (Parthasarthy, 2002): Karalar gounders without tattooing marks and Vellalar gounders with tattooing. The society is patrilineal. The entire composite extended families are involved in cultivation and share the produce. Malayali marriages are by elopement, force or by negotiation. The Malayali traditional political organization has close affiliation with their territory within the hills. The territories are called nadus and are headed by Nattans.

KEYWORDS

•Cultural Diversity

•Eastern Ghats

•Ethnic Diversity

•Ethnic Societies

•Origin of Ethnic Tribes

REFERENCES

Carney, J.A. & Rosomoff, R.N. (2009). In the Shadow of Slavery. Berkeley, USA: University California Press.

Chauhan, K.P.S. (1998). Framework for conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity: Action plan for the Eastern Ghats region. pp. 345–358. In: The Eastern Ghats—Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. Hyderabad, India: ENVIS Center, EPTRI.

Gadgil, M., Joshi, N.V., Manoharan, S., Patil, S. & Shambu Prasad, G.V. (1996). Peopling of India. pp. 100–129. In: D. Balasubramanian & N. Appaji Rao (Eds.). The Indian Human Heritage, Hyderabad: Universities Press.

Krishnamurthy, K.V., Murugan, R. & Ravi Kumar, K. (2014). Bioresources of the Eastern Ghats. Their Conservation and Management. Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehra Dun.

Merlin Franco, F. Narasimhan, D. & William Stanley, D. (2004). Patterns of Utilization of natural resources among tribal communities in the Koraput region. In: Abstracts- Natl. Sem. New Frontiers in Plant Biodiversity Conservation. TBGRI, Tiruvanandapuram, India. pp. 149.

Parthasarathy, J. (2002). Tribal people and Eastern Ghats: An anthropological perspective on mountain and indigenous cultures in Tamil Nadu. pp. 442–450. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India.

Pullaiah, T. (2001). Draft Action Plan-Report on National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan: Eastern Ghats Ecoregion, Anantapur, India.

Ratna Kumari, M., Subba Rao, M.V. & Kumar, M.E. (2007). Tribal groups and their Podu type of Cultivation in Andhra Pradesh. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS center, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 384–385.

Sandhibigraha, G., Dhal, N.K. & Mohapata, B. (2007). Preliminary survey on folklore claims of anti-arthritic medicinal plants of Gandhmardan-Harishankar hill ranges of Orissa, India. In: Abstracts-Int. Sem. Changing Scenario in Angiosperm Systematic. Shivaji University, Kolhapur, India. pp. 162–163.

Sastry, V.N.V.K. (2002). Changing tribal economy in Eastern Ghats: Problems and Prospects. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS center, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 49–495.

Sathya Mohan, P.V. (2006). People. ENVIS-SNDP Newsletter. Special issue. pp. 10–17.

Scholz, C.A., Johnson, T.C., Cohen, A.S. et al. (2007). East African megadroughts between 135 and 75 thousand years ago and its bearing on early-modern human origins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104, 16416–16421.

Singh, K.S. (1993). Peoples of India (1985–92). Curr. Sci. 64, 1–10.

Swain, P.K. & Razia Sultana. (2009). Tribal Communities of Eastern Ghats. EPTRI-ENVIS Newsletter 15(2), 3–6.

Thangaraj, K. (2011). Evolution and migration of modern human: influence from peopling of India. In: Symp. Vol. on New Facets of Evolutionary Biology. Madras Christian College, Tambaram, Chennai, India. pp. 19–21.

Vinod Kumar (2007). Sustainable development perspectives of Eastern Ghats-Orissa. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserve. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS center, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 558–575.