CHAPTER 3

ETHNOBOTANY OF WORLDVIEWS AND BELIEF SYSTEMS OF EASTERN GHATS AND ADJACENT DECCAN REGION

K. V. KRISHNAMURTHY

Department of Plant Science, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli–620024, India

CONTENTS

3.2Rituals and Plants Associated with Them

ABSTRACT

This chapter deals with plants that are associated with the worldviews and belief systems of the ethnic communities of Eastern Ghats and the adjacent Deccan region of India. Plants have played a vital role in the evolution of societies and cultures of these ethnic communities. They are connected to the natural, spiritual and human domains and their interactions. The information on plants and their validity and importance in traditional worldviews and belief systems have been obtained through three approaches: utilitarian, ecocultural and cognitive. Plants often symbolize rituals and the correct interpretation of rituals provides insight into various aspects of human behavior while using a plant or its product. This chapter covers aspects relating to plants involved in life cycle, social, religious, agricultural and food rituals. It many cases, the origins of such plant symbolisms associated with various rituals have become largely obscured and unfortunately, only their so-called ‘superstitious’ and ‘occasional irrational’ tags remain, leading to the questioning of the rituals themselves. A critical reexamination of the importance of this plant symbolism in rituals is urgently needed.

3.1INTRODUCTION

It is generally believed that societies, cultures, worldview and belief systems were simultaneously evolved in different regions of the world which formed parts of various migratory routes of modern human species (Homo sapiens) when it left the African continent around 70,000 years ago. It is also generally believed that the evolutions of all the above is inextricably related to one another and that this evolution was also dependent on the environmental conditions that existed in the different regions of original human occupation. It was also dependent on the threads of social ideas, cultures, worldviews and belief systems that the settling human populations already possessed on its long journey before settling down in a region. Hence, it is natural to find two distinct components in all the four: (i) the components that are common to all ancient traditional ethnic communities; and (ii) the components that are unique to each one of these communities. It is also possible that some of the first category components might have had a parallel or independent evolution in these communities.

The pockets of human populations that got settled on specific locations of the world and have been associated with these locations for a very long time are called indigenous or traditional communities. The interrelations between different members of an indigenous community that enable better social life constitute social organization or society. All ethnic societies normally have a distinct territory, are endogamous and are often subdivided into clans, subclasses, classes, etc. The social relationship amongst members of such endogamous ethnic groups is governed by kinship and mutual help. Their beliefs extend these interrelationships from the social to the natural environment. Each of these societies pursue tradionally well-defined modes of subsistence, have similar levels of access to various environmental resources and are egalitarian (Gadgil and Thapar, 1990). A very important component of the ethnic society is the shaman, the spiritual leader, and shamanism is central to the well-being and the continued conservation of the ethnic society and its culture, worldviews and belief systems.

It is often difficult to define culture and many definitions are available. It is defined by Gadgil (1987), from a biological perspective, as the acquisition of behavioral traits from conspecifics through the process of social learning. These behavioral traits, which include traits related to knowledge, belief systems, arts, morals, laws, customs and any other capability and habit acquired by people as members of a society, are socially transmitted from one generation to another (Tylor, 1874). Culture, thus, is a man-made component of the environment (Parthasarathy, 2002).

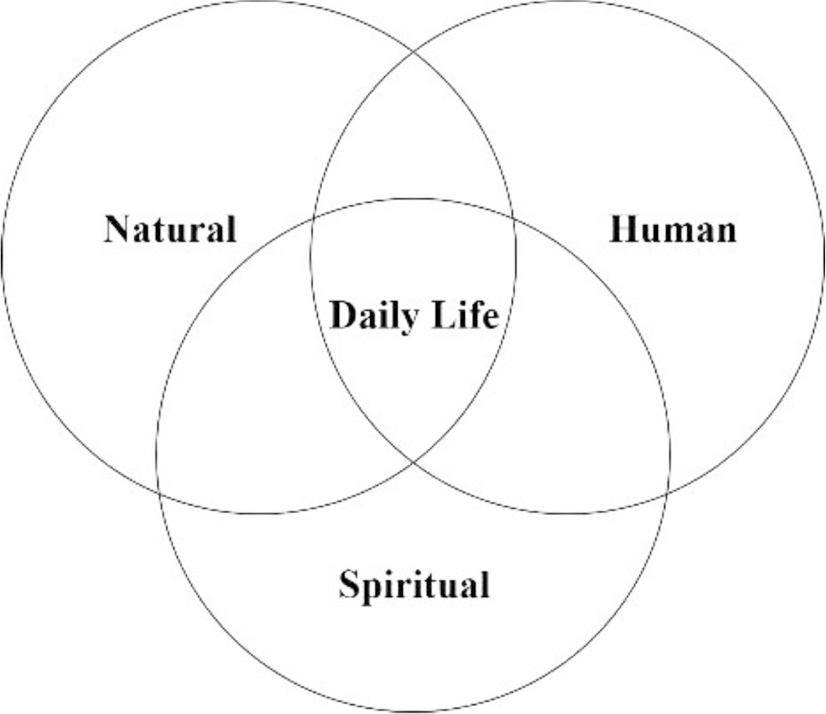

The knowledge systems known to indigenous/traditional societies are known as indigenous/traditional knowledge systems (IKS/TKS). TKS is also known by terms, such as Worldviews and Cosmovisions. All these terms refer to the different ways of perceiving, ethnic societies/communities. The different worldviews of various ethnic societies have come to gain knowledge about the environment and its living and non-living components around them. However, more often, worldviews are expressed by conceiving life’s knowledge obtained during a life time in terms of three inter-related and often inseparable domains (or spheres or worlds): Natural (or Material), Human (or Social) and Spiritual (Figure 3.1). The natural world provides the message from the spiritual world to the human world.

It is to be emphasized here that, to a very large extent, the ability of an ethnic community to sustainably use the environmental resources available around it is determined by the above worldview. This worldview always includes knowledge that is not only limited to the world which can be perceived with human senses and which can be explained in a rational/scientific way, but also to a world beyond human perception and existing rational/scientific explanation. Thus, knowledge, according to traditional worldview, is a combination of that which is true and rationally explained by science, and that which is believed by humans (=belief systems); thus, truth and belief go together. This worldview is also qualitative, practical, intuitive and holistic. TKS in the natural domain includes thematic areas related to specific resource generation/collection, agricultural, health and other practices. It includes knowledge about the physical world and the biological world and their constituents and material resources. The human domain implies the social life of people and includes knowledge about local organization, community life, family ties, local spiritual leadership, management of local resources, mutual help, conflict resolution, gender relations, and language and communication. The spiritual domain includes knowledge and beliefs about the invisible world, divine beings, spiritual forces and ancestors and transmitted through values and practices, such as rituals, festivals, etc. None of these three domains exists in isolation; all the domains together reflect the expressions of a unity. Some ethnic societies consider the confluence of these three domains as giving rise to a fourth domain/sphere called daily life domain. It is in this fourth domain that all the shared practices, such as the necessary techniques and technologies for the continuity of life and the social, material and spiritual reproduction take place for all humans. When a man respects his natural sphere and adapts himself to it spiritually and socially, nature will maintain its equilibrium and supply him what he needs. Thus, “all is related to all.”

FIGURE 3.1Interactions of three domains that results in worldviews.

The ability of the ethnic communities to use the local resources to a large extent is determined by the above worldview. There are six categories of resources: (i) Natural resource (landscapes, ecosystem, climate, plants and animals); (ii) Human resources (Knowledge, skills, local concepts, learning ways and experiments); (iii) Human-made resources (buildings, infrastructure, tools, equipments, etc.); (iv) Economic and financial resources (markets, incomes, ownerships, price-relations, credits, etc.); (v) social resources (family, ethnic organizations, social institutions and leaderships); and (vi) Cultural resources (beliefs, norms, values, rituals, festivals, art, languages, lifestyle, etc.). This division is a further elaboration of the concept of three domains mentioned above.

Information relating to worldviews on plants and their validity and importance have largely been obtained through three main approaches (Cotton, 1996) in the ethnic societies of the study region, as in most other ethnic societies of the world: (i) Ecocultural approach; (ii) Cognitive and Socio-cultural approach; (iii) Utilitarian or Economic approach. The first approach invokes certain traditional cultural practices involved not only in foraging but also in settled agriculture, such as those involved in sowing, transplanting, and harvesting taboos and/or rituals. Many traditional cultural practices involving plants may at first appear irrational, but in reality these practices have very important and significant functional consequences. The cognitive approach tells us how the various ethnic societies perceive plants and also how such perceptions are influenced by sociocultural factors and spiritual beliefs. This approach invariably involves rituals/symbolic behaviors that fall in the realms of society, religion, magic, spirituality and supernatural domain. Utilitarian approach records how different ethnic cultures use the plants for their various materialistic needs. All the old ethnic communities in the study region are Dravidians. In the account that follows only ecocutural, cognitive and sociocultural approaches and plants associated with these approaches are dealt with; utilitarian approach to plant utilization is given importance in a few other chapters of this volume.

3.2RITUALS AND PLANTS ASSOCIATED WITH THEM

3.2.1 DEFINITION AND TYPES OF RITUALS

Rituals may be defined as any serious and voluntarily conducted act/event at the individual, family or community level with the appropriate and correct behavioral and procedural formalities to gain impetus to lead a purposeful life in a serious and symbolic manner. Thus, rituals make people to lead life with serious and virtuous goals, as they add auspiciousness and sanctity to life (Eliade, 1959). Rituals help people to accept, without questioning, the importance and sanctity of energy and the myths and belief systems associated with this energy. Rituals are seen in all ethnic communities of the world, including those studied in this chapter, and are characteristic of all religions, whether basic or formal, primitive or advanced. According to basic religious and Hindu religious philosophies of India, which are mainly followed by the ethnic communities in the Eastern Ghats and adjacent Deccan region, human life is intimately connected to the cycle of life, right from birth until death and that between these two phases there is a sequential change from childhood to senescence. Since, human life in these ethnic societies is also culture-related, the biological phase changes are also subjected to the influences of culture. In other words, life cycle changes are also socio-cultural changes. In fact more than life cycle changes, it is at the socio-cultural level that life-phase changes get more polished. Each phase change gets culturally entangled to very specific ritualistic phenomena or gets itself ritualized. The ritualized phase changes become life cycle rituals. Birth, naming of the child, ear-boring, birthday celebrations, attaining puberty, marriage, nuptials, pregnancy, child-bearing, childbirth, and ultimately the death of the individual, etc. are the most important life phases which are ritualized in the ethnic societies of Eastern Ghats and adjacent Deccan region.

In addition to these life cycle rituals, there are other rituals that are associated with social, economic, religious, agricultural, food and arts/crafts activities of these ethnic communities. Thus, rituals are multifaceted. The nature of rituals changes with many factors, such as time, place and environment at which they are conducted, as well as on the aim and need for the conduct of a ritual. Although the rituals of each ethnic community have unique characteristics, we can also find common characteristics between them. The common ones are the following: Thought-related action-oriented, conduct-related, voluntary, visible, esthetic, periodic, repetitive, auspicious, collective, social, non-entertainmental and having rational and instrumental components. Each ritual also has a unique role, unique character, unique action and unique way of conduct. Cults like totemism (see a subsequent page for more details) followed in many ethnic communities in the study region depend on belief systems and practices associated with them. These belief systems and rituals are inseparable, not only because rituals are often the role manifestation of otherwise imperceptible ideas but also because they react upon and, thus, alter the nature of the ideas themselves. The rituals serve and can serve to sustain the vitality of beliefs and to keep the beliefs from being effaced from memory. Rituals help to protect the integrity of the society and its culture, keep them intact, remove all contradictions and oxymorons, bring about cooperation among people of the community, protect all the values that the society should preserve, and conserve societal relations, carry out the aspirations of the individuals of the society in order to make him a valuable component of the society, etc. Rituals of ethnic communities in the study region can be classified in various ways: technical vs ideological, positive vs negative, conformatory vs transformatory, separatory vs incorporatory, auspicious vs inauspicious, prescriptive vs performatory, etc. Ritual is known in ancient Tamil language as Karanam.

With all the rituals, plants or plant products are invariably associated. They often symbolize rituals and an analysis of these symbolic items basically involves the recurring themes of all rituals, the correct interpretation of which can provide insight into certain aspects of human behavior while using a plant or a plant product. In many cases the origins of such plant symbolism have become largely obscured and only their so-called ‘superstitious’ and occasional ‘irrational’ tags remain, leading to the questioning of the rituals themselves.

3.2.2LIFE CYCLE RITUALS

3.2.2.1BIRTH RITUALS

Birth rituals are very special for certain ethnic societies. Birth indicates the addition of one body and a soul to the earth. During this ritual the umbilical cord and the uterine liquid that comes out of the vagina of the mother are considered as very sacred and auspicious. These two are buried behind the house and the burial mound is considered sacred until 10th or 16th day after child birth depending on the community. The mound is enclosed by a fence made of Palmyra or coconut leaves and rachis. The mother takes bath within this fenced enclosure until the 10th or 16th day as the case may be. On that day three full plantain leaves are put in front of the mound on which are served cooked rice. Sambar prepared with salted dried fish or black pepper (depending on non-vegetarian or vegetarian family) is poured on the rice; also put are either boiled eggs or balls made of palmyra jaggery mixed with Alpinia rhizome paste. Then a wooden twig/stick is inserted vertically on the rice. Also kept near the banana leaves is a vessel filled with water and sprinkled with floral petals. This is followed by worship to God to protect both the mother and the newborn child. Then the food on the three leaves is eaten respectively by mother, the woman who helped her during childbirth, and the nurse who helped her medically to yield the child. The child is kept over the burial mound. The whole ritual is conducted by women only and men are not allowed. The burial pit plus the mound over it are considered as equivalent to the Yoni on vagina, the stick/twig the male organ and the liquid sambar poured over cooked rice is the fluid that comes out of uterus along with the child (Paramasivan, 2001).

Couple who do not have a child and who want to adopt a child follow an interesting ritual. The couple gives a cup/vessel full of powered paddy husk to the person who gives her child for adoption by the couple. This means that the child for adoption is not got free but by paying husk in return.

3.2.2.2MARRIAGE RITUALS

The most important ritual connected to marriage in many ethnic communities of the study region is the tying of the mangala sutra (Thaali in Tamil and Telugu) or the sacred cotton thread soaked in turmeric dye on the neck of the bride by the bridgegroom. Wearing this sacred thread until the death of husband is a must for the married women. Once this thread is tied, all relatives of both the bride and bridegroom (both patrilineal and matrilineal) bless the newly-married couple by showering on them with rice grains stained with turmeric dye. In the most ancient Dravidian, particularly Tamil, culture, there existed only secret love affair (called Kalavu in Tamil) that was either permitted or not by the parents and there was no marriage per se. However, sooner or later this kalavu system gave rise to the marriage system that was more and more tagged with chastity through wearing of Thaali. No remnant of Thaali was discovered in Adichanallur excavations conducted in the southern part of Tamil Nadu. Initially the thaali thread was tied along with flowers of Jasminum auriculatum (which represent chastity) before it is put on the bride. The most ancient foraging communities wear a black thread to which a collar bone (Clavicle) was tied. The dying of thaali with turmeric was done much later in Dravidian history but not earlier than 10th century CE according to many Tamil scholars (Paramasivan, 2001; Krishnamurthy, 2007). In the marriage hall/stage are kept many colored (often yellow/red) pots (called Arasaani pots) filled with turmeric water. These indicate that the marriage should lead to wealth, prosperity and fertility, as turmeric symbolizes auspiciousness. Some tribes also keep a pair of winnowing pan (muram in Tamil), made of bamboo, again tinged with turmeric dye. Betel leaves, and coconuts, plantain fruits, areca nuts, etc. are all kept on a pan in the marriage stage always in even numbers. Banana trees one on either side are kept on the entrance to the hall or on the marriage stage, often along with the inflorescence, again in pairs, of coconut, palmyra, phoenix species or very rarely in northern Eastern Ghats region Corypha species tied to the banana stems. The keeping of all the above in even numbers signifies bilateral symmetry that is reflected in the life of the people of these ethnic communities. This is in contrast to the death rituals (see later) where things including plants/plant parts used are always in odd numbers.

The marriage hall/stage specially houses laticiferous plants or their twigs in the marriages of many ethnic communities of the study region. This symbolizes fertility of the woman to get married, especially the lactating ability of her breasts after child birth and the child-bearing fertility of her womb. This ritualistic symbol is characteristic of the matriarchal society, according to Turner (1963), although it should be mentioned that this ritual is followed in ethnic societies which are also patriarchal. Probably, all the ethnic societies were originally matriarchal and then some of them became patriarchal. Ritualistic plants, such as banana, coconut, palmyra, phoenix, Corypha, Ficus, Mango, turmeric and a few others used in the marriage venue are believed to convert the mortal bodies of the marriage couple into divine couple and godly status in the luminal space of the marriage hall. The wearing of floral garland and new cotton clothes and new cotton thread by the bride also helps to bring about this change.

3.2.2.3DEATH RITUALS

In the study region, the ethnic communities either bury or burn the dead people depending on the community (Paramasivam, 2001; Rajan, 2004). The dead body is buried in specially devised structures in the ground or is put in a huge mud pot (Thazhi in Tamil) which is then buried. Along with the dead body grains of rice, sorghum or minor millets are put inside the pot or in the pit. Such pots have been discovered in several parts of ancient Tamil country through archaeological excavations (Rajan, 2004). Burning the dead is considered by some as more ancient than burying since the latter is often believed to have arisen along with the evolution of agriculture. Many death rituals are quite opposite to the ones that are conducted during the auspicious phases of the life cycle like birth or marriage. This is indicative of bilateral symmetry, as already mentioned. The death rituals are intimately connected to the concept of rebirth after death. The cycle of rebirth includes humans and animals, but does not include plants (i.e., plants after death do not have rebirth) in all the ethnic societies. However, as early Hindu texts analyze about what may happen to a dead person, plants are brought into the process. Burying the entire dead body or burying the bones of the dead after burning are considered as equivalent to sowing seeds of a crop plant and the emergence of seedlings from them as equivalent to rebirth/resurrection after getting a new life. Plants are also believed to feature as a destination or a way-station for parts of the dead person on journey after his death in the life cycle process. For example, his hairs go to the herbs and his head to the trees. In other words, the dead are born on earth again as “rice and barley, herbs and trees, as seasame plants and beans” (Radhakrishnan, 1993). Just before burying or burning the body of the deceased the patrilineal relatives stuff the mouth of the dead with rice grains. Thus, plants and their seeds are centered to the ritual mechanics that cycle the deceased into his next existence.

In the Saanthi or peace-making death ritual performed by many ethnic communities, after collecting the bones of the burnt dead person, flowers, wood, grass and butter/ghee are used by the survivors of the dead person to renew his life after the sweeping and eleaning the site of the mound using special ritual twigs of Palasa (Butea frondosa) tree, plowing the site and then sowing seeds of various herbs before pouring out the bones. Over the top of the mound, the worshipper sows paddy grains and covers the mound with Avaka plants for moisture and Dharba grass (Imperata cylindrica) for softness (Kane, 1990–1991).

Many offerings of cooked rice and vegetables are made throughout the death rituals. One particular instance that exemplifies the role of plants in death rituals is the Sraardha ritual. In this ritual offerings are made for the pitroos, the immediate paternal ancestors of the worhipper so as to enable the deceased to be received by them to be among them. This ritual uses pindum or ball of cooked rice, which represents the dead body. This pindum is worshipped using incense, flowers, ghee, white threads/clothes and a cup of water with sesame seeds. This worship is done normally for 10 days, although in some communities this period may be shortened or prolonged by a few days. Each day the number of cups is increased by one. It is believed that the use of pindum ritually creates the new body of the deceased for life in the community of ancestors and eventually for rebirth for himself among the world of humans. Thus, this ritual places plants at the center of the ritual’s transformatory process. The material that makes up the pindum is invariably rice, although some minor millets are used in some ethnic communities of the study region, and barley in some communities in northern-most Eastern Ghats.

The Koyas of Eastern Ghats symbolically offer material objects like grains, palm liquor (from Caryota urens), new clothes, money and a cow’s tail by placing them on a cot beside the corpse and the whole cot is placed on the funnel pyre with the feet of the corpse towards the west. They have a ceremony on the 11th day after death called ‘Dinalu.’ At this time they believe that the spirit of the dead comes back and resides in the earthen pot called ‘anakunda’

3.2.3RELIGIOUS RITUALS

All the traditional ethnic societies of the study area follow Hinduism, which believes in the existence of many gods. It is well-known that Hinduism is a very diverse, varied and broad-based religion and has no identified founder. It originated in India perhaps as an amalgamation of vedic religion and the various basic religions of the different ancient ethnic groups. However, under the broader umbrella of Hindu religion, it is the worldviews of basic religions that are still dominant in most, if not all, ancient ethnic groups of the study region. As per basic religions, people considered themselves dependent on various natural forces, which are supposed to be controlled by Gods/spirits to whom they can pray, worship or make sacrifices for support (Krishnamurthy, 2005). The basic religions include animism, bongaism, totemism, naturalism, ancestral worship and polytheism (Hopfe and Woodward, 1998; Pushpangadan and Pradeep, 2008). Although basic religious customs, rituals and taboos still prevail in many cultures, there is a gradual transition from these basic aspects to those of mainstream Hinduism. Village/family gods/goddesses are still the most popular among the tribal groups than formal and mainstream gods. The village gods/goddesses are believed to protect crops, irrigation water, harvested produce, etc.

The ultimate goal of all religions is reaching god and thereby truth. Religious show the way as to how humans must relate themselves to god and truth. Praying, worshipping and offerings are manifestations of this relationship. Because of their centrality in human lives, plants are often the objects of sacred attentions and religious activities. Besides being the objects of worship themselves, plants come to play important roles in religious practices, such as fuel for the sacred fire, as wood for ritual implements, as the materials (such as leaves, flowers, fruits, seeds and even whole plants) used for worship of god, as food offered for gods and priests, and as prasaadams given to devoters (Findly, 2008). For example, Lord Shiva himself is conceived as a yupa fashioned in Khadira or sami wood, and both woods are believed to have fire in them.

All the basic religious, and particularly totemism, involve some form of identification between tribes or between clans of a tribe and an animal or plant species (Zimmer, 1935; Whitehead, 1921; Subramanian, 1990) or a natural phenomenon/object. It is a belief in the mysterious relationship between plants (and animals) on the one hand and humans on the other and their veneration and propitiation as totem objects. The totem is often considered by many tribes as the ancestor of the clan and its relationship implies certain common characteristics as well as taboos in eating or foraging/hunting. Such a relationship is articulated as the concerned plant (or animal) is believed to have helped or protected the respective ancestors of a clan, or it had been proved to be of some use. The totem plant is held in great respect and reverence and it should not be hurt or destroyed. In some cases, its utilization is not normally permitted. The dead totemic plants (and animals) are given full honor and are attended to in their last rites. The best way thought by these ancient ethnic groups to protect plants (and animals) was to create a sense of fear, respect or faith in human minds towards the plants as abodes of gods/spirits. Deities living in various trees are not all the same, however, and, they reside there for different purposes. Tree deities are spirits of fertility, prosperity and protection. The early understanding of the nature of a deity inhabiting a plant is how the deity relates to the health of humans. That is, those plants with healing properties house deities of health and prosperity, while those that cause symptoms of disease house deities of wickedness and debilitation. Concerning the latter, many examples of plants are being used to protect humans from curses, witchcraft, sorcery and black magic-inflicting enemies. Trees can also house the spirits (Preta or ghosts) of the recently departed (dead) who, while still in states of transition, are unsatisfied and need human attention. Thus, plants are considered as sentiment beings equal to humans in that they, too, can become pretas –spirits in the process of being remembered on their way to rebirth. Services by the deity living in a tree are much like the services offered by the tree itself.

The concept of Sthalavriksha (=temple trees) is an extension of tree worship practiced in basic religions of ancient S.E. India, when these religions got transformed into formal religions, particularly when institutions of worship like temples developed. Even today many ethnic societies in this region worship trees. The names of presiding deities in many temples are based on or related to tree/plant names (Varadarajan, 1965; Kalyanam, 1970). In 270 temples (but 275 according to Sundara Sobitharaj, 1994) of Tamil Nadu, nearly half have one of the 80 species of trees/plants as the sthalavriksha. These are mostly trees, although there are shrubs, subshrubs, herbs, climbers and even grasses (Swamy, 1978; Sundara Sobitharaj, 1994; Krishnamurthy, 2007). The concept of sthalavriksha must have been born just before 7th century CE in Tamil country as a result of the evolution of formal religion and the development of temples as major religious institutions. The idea that each temple should have a temple-plant seemed to have been formalized gradually. Krishnamurthy (2007) has given a comprehensive list of all the temple plants of Tamil Nadu and adjoining regions of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Kerala, which formed part of the ancient Tamil country. These temples include not only Saivite (74 species of plants) but also Vaishnavite (18 plants) temples and 12 plants were common to both. The same plant species may serve as the temple plant of more than one temple. There are also a few temples with more than one temple tree. For instance, Bilva (Aegle marmelos) is the temple tree of 26 temples, Vanni (Prosopis spicigera) of 26, Konrai (Cassia fistula) of 22, Punnai (Calophyllum inophyllum) of 18, Jack tree (Artocarpus integrifolia) of 17, Mango (Mangifera indica) of 12, and palmyrah (Borassus flabellifer) of 9 temples. Another way in which trees/plants were attached religious sanctity by the ethnic societies of this region has been to associate them with the 27 stars recognized and named by ancient Hindus. It is to be stated here that even before a temple was built, its temple tree was decided by the temple committee. The builder first mentions the place where the temple has to be built and the presiding deity to be enshrined in the temple. Subsequently, the architect and the priest identify the star related to this deity and accordingly, the shape and size of the idol are decided. The details on the plants assigned to each of the 27 stars are found in Krishnamurthy (2007).

Sacred groves, Nandavanas (temple gardens) and temple tanks that are associated with temples form another important aspect of sanctity and importance given to plants by the ethnic communities of the study region. Sacred groves are parts of natural vegetations that are always associated with the so-called minor temples that are given importance to by basic religions and are seen in village/rural/forested regions, in contrast to Nandavanas which are newly established in association with larger temples (of Hinduism) in towns/cities. In the former case, sacred groves come first and ‘temples’ are established subsequently, while the reverse is true in the latter. The concept of sacred groves can be said to have evolved even at the hunter-gather stage (Kosambi, 1962), while that of Nandavanas is of post-agricultural evolution. There are more than 50,000 sacred groves in India of which in the study region covered by this book there are about 3,000 groves; 500 of these are fairly well-known. The sacred groves are places of great power and people have traditionally set them aside as places of physical and spiritual benefits to humans and non-humans alike. They are one of the finest instances of traditional ways of reverence to plants. Plants in sacred groves cannot be cut and several other taboos are associated with sacred groves (Krishanmurthy, 2003). The deity in the temple associated with a sacred grove may be male or female. No one owns the sacred grove and it belongs to everyone in the community.

Temples and the sacred groves/nandavanas/tanks associated with them have strengthened the tie between religions and plants. In all cultural, educational and religious activities and rituals associated with temples, plants and their parts (leaves, flowers, fruits, seed, etc.) obtained from nandavanas/sacred groves and tanks are used; particularly for the daily worship of the deity and the offering of Prasadams to the devotes (see details in Krishnamurthy, 2007).

Specific species of plants are associated with specific gods in the formal Hindu religious practices of the study region, as is evident from literary and epigraphic evidences as well as from temple murals/paintings. Generally Saivite gods were worshipped with leaves of bilva (Aegle marmelos) and flowers of Leucas aspera and Cassia fistula, while vaishnavite gods with tulsi (Ocimum spp.) leaves, flowers of Mimusops elengi; Lord Ganesa is worshipped with the grass Cynodon dactylon. Certain plants or their parts were offered to all gods: coconut, betel leaf, betel nut, lotus flowers, Nerium flowers, etc. Each god was also assigned specifically a plant and its flower or leaf: Cassia fistula for Lord Shiva, Neolamarckia cadamba for Lord Muruga, Nymphaea spp. For goddess Lakshmi, Nelumbo nucifera (white variety) for Goddess Saraswati, Mimusops elengi for Lord Vishnu, Saraca asoca for Mahavir, Nerium oleander for goddess Kali, Bauhinia spp. for Lord Indra and so on. Later on, this specificity was corrupted and all the above were used for all gods/goddesses. Sandal paste is continued to be used for anointing the idols as also coconut water for holy bath of idols. Camphor was beginning to be used in the Sanctum Sanctorium of temples so as to enable the devotees to see the idol, while oil cloth wrapped on woody twigs was lighted in village temples (=Teeppandam or torch of fire) for the same purpose. The oil used for burning temple lamps was originally obtained from the seeds of Madhuca longifolia, although this was subsequently replaced by other oils, such as sesame oil.

Prepared plant food items were being offered to god, often as substitutes for live animals like chicken, goats, etc., or along with them as sacrifice. One of the oldest and most popular food items offered to village deities is pongal, a preparation made of rice, pulses and ghee. It is often prepared at the community level (Paramasivam, 2001; Krishnamurthy, 2007). The offered pongal was known as Madi or Kulirthi in Tamil. During the Thaipoosam religious festival Pongal is offered to God, by the whole community, along with Colocasia, elephant foot yam, palmyra seedling tuber, etc. Pongal is also a ritual food throughout the Tamil Margazhi month (December–January) for most communities. Pongal represents an offering to God from the raw plant to the cooked state of the same, a trend that was common to all ethnic societies. Some consider the pot in which pongal is prepared as the goddess, and the boiling rice as the destructions of male chauvinism. When pongal offering is done at the community level, each family prepares it by using only palmyra leaves as the fuel. Another food item offered by some traditional communities in the arid regions is Paanakam (a mixture of palmyra jaggery, tamarind, ginger and water). Yet another item is ulundu sundal (a preparation of boiled and salted black gram). In some societies, cooked rice is not offered, but only rice soaked in water and germinated pulses. These communities, on critical analysis, were found to be originally foraging nomadic communities. In S.E. Indian Hindu temples food items offered as sacrifice (Padayal in Tamil) to God and given as prasaadams to devotees were always vegetarian. In all likelihood this practice began in the 7th century CE, after the Bakthi movement. A partly dilapidated epigraph discovered in 1927 (epigraph number 127) mentions ten different items of food as dear to Lord Shiva, but details could not be obtained. A 9th century CE epigraph of king Varagunapandian found in Ambasamudram in Tirunelveli distirct, Tamil Nadu mentions a list of food items offered as ritual sacrifice including Pulikkari, Pulugookkari, Porikkari, Kummayam, etc. (Epigraphica Indica IX. No.10). A 11th century CE epigraph of king Veerarajendra Cholan (Epigraphica indica XXI. No.30) mentions, in addition to the above, Milagukkari. A 16th century Vijayanagara kingdoms’s epigraph reveals that different kinds of food items were offered to Gods and these included vegetables, Kariamudu, Vaaikkamudu, Neyyamudu, Kootu, Pachchadi, Kadukkorai, Aappam, Vedhuporiaappam, Vadai, Idli, Sugian, Daddiyannam (Curd rice), etc. Some of these have either been lost, or have had name changes, so as not enabling us to identify them correctly.

Sacrifice to Gods/Spirits arose in Totemism which recognizes totems or emblems which are usually plants or animals. In all ethnic societies, animal sacrifice to Gods/Spirits was offered to begin with during cultural revolution and it is continued to be done even today in many societies at least on special religious rituals. Sooner or later animal sacrifice was replaced by plant sacrifice. Initially both animal and plant sacrifices were done and finally plants replaced animals totally in formal religious institutions like big temples. The blood of chicken or goat is mixed with rice and offered in cane baskets to Lord Muruga, according to ancient Tamil literary sources. Along with Tinai rice (a millet) and flowers, goat and chicken were also offered. However, blood was replaced by red dyes obtained from plants and these were mixed with rice or stuffed into lemon or ash gourd fruits and offered to Gods. Such a transition is also seen in many ethnic communities in other parts of the world like the Jews and Nuers. Evolution from animal sacrifice to plant sacrifice did not change the ideology and theoretic basis of a ritual but only brought about an operational and technical chance (Evans Pritchard, 1956).

3.2.4AGRICULTURAL RITUALS

As in many other ethnic cultures of the world, most ethnic societies of Eastern Ghats and adjacent Deccan region follow agriculture for their sustenance and food security. The agricultural cycle in this region is hedged around with ritual and ceremonious activities directed towards furthering the powers of fertility manifest in soils and in various crops to ensure a good harvest. Hence, agricultural activities, such as planting, harvesting, weeding, etc. in these societies are associated with belief systems, taboos and rituals. Agriculture is treated as a pious and virtuous act by all these societies, as in ethnic societies elsewhere in the world (Salas, 1994). These rituals are related to the type of agricultural activity and the time of the year, and take place at various levels (individual/family/community), and include social conduct based on the concept of reciprocacity. At family level simple rituals are performed more or less on a daily basis at home or in the agricultural field to appease the natural spirits and to attract good luck and abundance of crop yield. Many rituals are combined with a sacrifice or offering of an animal or a plant food preparation, such as pongal. For example, in February during the seed festival known as ‘Biccha Parbu’ the Samantha tribe of Eastern Ghats worship the village Goddess ‘Jakiri Penu’ by offering animal sacrifices and then they sown seeds mixed with sacrificial blood of animals. Offering of pongal (also called pallayam offering or Padayal) signifies the fact that the space inside the pot for pongal preparation is symbolically converted into a space in the agricultural field and the prepared pongal is symbolically equivalent to the crop yield. Most often this pongal padayal is carried out at the community level.

3.2.5FOOD RITUALS

Human subsistence in all traditional societies signified more than the food that fed commerce (Carney and Rosomof, 2009). It asks us to engage the broader relationship of food to culture, and culture to identity. According to the belief systems of many traditional societies, including those of the region studied here, food is provided by Gods/Spirits, often in response to prayers and gratitude, expressed through a variety of ceremonial rituals. The Hindu texts, which have been the source of inspiration to many ethnic societies of this region, say clearly that plants are most often necessary to make food for Gods and priests to eat. Some of these texts specify ten cultivated grains that are to be used in foods associated with rituals: rice, barley, sesame, beans, millet (probably black gram) and Vetch. When used for sacrificial purposes, these grains are ground and soaked in curd, honey or ghee before being offered as part of on oblation. Cakes made of different grains are offered in different directions, often wrapped up in leaves of Udumbara (Ficus glomerata) tree. Rice cake, for example, is placed on the eastern direction. Even trees were worshipped with ritual plant foods, often at night. The foods offered include milk, porridge, sweets, rice, curd, sesame and “eatables of various kinds.” Food offerings are done to trees also before they are cut down for some purpose.

The food taken by many ethnic communities in the ancient Tamil country is ritualistic. In many communities food taken on Tuesdays, Fridays and/or Saturdays are purely plant-based; so also throughout the Tamil month of Purattasi (September–October). In many villages, people consume only vegetrarian diet during the village religious festivals, particularly after the temple flag has been hoisted (=Kaappukattal in Tamil) (Paramasivam, 2001). During these days, in many families, the following vegetable items are not cooked: bitter gourd, some pulses (especially those that are not native) and Sesbania leaves. The food that is consumed includes thick porridge of black gram, puffed rice, cooked rice flour sweetened and added with coconut shreds, Kummyam, sesamum seed preparations, etc.

3.2.6SOCIAL RITUALS

A number of social rituals are conducted. These rituals are meant to keep the social harmony intact and to bond the members of a society together. Social rituals are related to festivals, pilgrimage, etc. Rituals practiced to remove the effects of ‘evil eye’ (removing Drishty) are very important in the social context. By ‘evil eye’ we mean the jealousy/hatred/cold war that is shown towards a person or family by some other member/family of an ethnic community for various reasons; the affected person/family believes that the evil eye is the reason for the suffering (in terms of health, finance or otherwise). Sometimes sorcery is also involved in creating the evil effects. In order to remove these evil efforts, the affected person or family follows certain rituals which it believes will not only remove the ill-effects but also will not reveal the identity of the person responsible for fixing the ‘evil eye in public. The latter preserves social harmony. The rituals conducted are either preventive or curative and take many forms. Hanging of an ash gourd (often with a ghost face drawn on it), an Agave plant upside down on a black-colored thread, or a bunch of chilly fruits sewn together along with a lemon fruit on a black thread in front of a house is done to remove the evil eye. Crushing of a lemon or ash gourd fruit stuffed with red dye in front of the house is done in some instances. Sometimes chilly fruits with or without betel leaves kept on water dyed red in a pan is spilled in front of the house or in the street corner. The reason why these particular plants are used for these rituals is not clear.

Another type of social ritual is related to the act of thanking God for fulfillment of vows, promises, oaths, etc. During these rituals the concerned person/family consumes plant food that is different from their daily food. Social rituals also include rituals connected to education. The Gurukula system of education was the prevalent system that existed among the ethnic communities of the study region. On the first day of initiation the child is taught to write the first alphabet on paddy/rice spread on a plate. The teachers or Gurus are paid Gurudakshina for educating the child. This concept arose in Buddhism and then got extended to Hinduism (Paramasivam, 2001). The students are given leave on the newmoon and fullmoon days and these days were called ‘Uva’ days. On these days the students give their teachers Dakshina (=fees) in the form of rice, vegetables and fruits. This rice is called ‘Uva rice’ which later on got corrupted as ‘Vavarisi.’ This practice is still continued in some ethnic societies,

Many social rituals involve laticiferous plants. It is under laticiferous trees like banyan and peepul (species of Ficus) that the meeting of ethnic communities including Panchayats are held. Women go around a Ficus religiosa tree praying for a child. Marriages and puberty functions are conducted in halls/venues kept with twigs of laticiferous/resinous/or other juicy trees like mango, banana, palms, Ficus, etc. These latex-secreting plants probably symbolize a matriarchal nature of most, if not all ancient ethnic societies of this region. These symbols are archetypal symbols. Panchayats below Ficus trees (symbolizes mother’s rule), worshiping of F. religiosa trees by women wanting to have a baby (matrilineal tradition), tying the umbilical cord onto a laticiferous tree (matrilineal reproductions), etc. are all represented by the same symbol to indicate a multifaceted and collective meaning and content. These symbols connect womenhood and fertility.

Rituals connected to festivals remove social problems and bring about social harmony. In village festivals, the idol of the village temple is brought from the temple to the place where it was originally residing and from there it is brought back to the temple. The whole place is decorated with festoons of plant leaves (particularly of mango, coconut, etc.) and flowers. Invariably pongal is offered along with sweetened rice flour cakes over which a ghee lamp (Maavilakku in Tamil) is lit. The idol is worshipped also with incense stick, betel leaf and nut, banana fruits, etc. The Banjara tribe celebrates the Teej festival in the month of August in a ritualistic manner. This festival is considered as important for unmarried girls who pray for better bridegrooms. The girls sow seeds in bamboo bowls and water them three times a day for nine days. The bowls are kept in a prominent place and girls sing and dance around the bowls. If the sprout from the seeds grow thick and tall, it is considered as a good omen for getting a better groom.

3.3HEALTH CARE RITUALS

Rituals connected to disease prevention and cure in the primitive ethnic communities of the study region are intimately related to a concept similar to Shamanism followed in some Latin American and African ethnic societies (Thaninayagam, 2011). The Shaman or spiritual leader (male or female) in this region is often known by the Tamil terms Poojary or Pandaram The shaman of Koya tribe is called ‘Buggivadde’; this tribe also has a sorcerer called ‘Vejji.’ The shanman is not only the village doctor but also the priest of the village temple and caretaker of the sacred grove associated with it. It is from the sacred grove that he often obtains the medicinal plants needed for the village community. He often practices medicine by combining with it spirituality, magic, godly faith and fear and sometimes even sorcery. Very often curing of diseases is ritualistic and combines one or more of the above. The poojary is regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of benevolent and malevolent spirits; he typically enters into a trance state during a ritual through ritual dances and practices divination and healing. The poojaries are often considered as intermediaries/messengers between the human world and the spiritual world. They operate primarily within the spiritual world, which in turn affects the human world. They are said to treat ailments/diseases by mending the soul. They also enter supernatural realms or dimensions to obtain solutions to problems afflicting the ethnic community. The restoration of balance results in the elimination of the disease (Eliade, 1972). Shamanism cannot be strictly defined as medicine, although healing is its main objective. The poojary has a vast knowledge on the medicinal properties of plants around him. Strange ceremonies, rites, rituals, chants, dances, colorful outfits, perfuming with incense and invocations are part of the shamanic world. Consumption of trance-giving plants is regarded as sacred is not hallucinogenic. Naokov (2000), for example, has elaborated his observations on shamanism after extensive fieldworks in Villupruam district of Tamil Nadu. The Nattar people, according to him, get cured through religion and magic-related actions, or mental and physical illness. He mentions of rituals related to Kuri-telling (=divine indication or forecasting/fortunetelling), black magic, counter black magic, sorcery, driving away of ghost/evil spirits, offering live sacrifice, etc. which are important in disease prevention/curing in this community. On getting subjected to these rituals, the person who gets a disease shows slow changes towards betterment while being watched by his relatives. Both prescriptive and performative rituals are conducted in this connection.

One ritual that is followed is tattooing (Akki-writing in Tamil) or suitable make ups on the body, aimed at disease curing. Anointing parts of body with clay or acquisition/control of body energies in an intelligent manner are also done through rituals and associated activities mentioned in the previous paragraph. Most of these rituals are often classified under technical rituals. Specific plants are used in this connection and the nature of relationship of these plants to actions like black magic and sorcery is not very clear. However, many of these plants contain tranquilizing or hallucinating principles in them.

KEYWORDS

•Cosmovision

•Domain Concept

•Eastern Ghats

•Rituals

•Traditional Knowledge System

REFERENCES

Carney, J.A. & Rosmof, R.N. (2009). In the Shadow of Slavery. Berkeley: University California Press.

Cotton, C.M. (1996). Ethnobotany. Principles and Applications. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Eliade, M. (1959). The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Eliade, M. (1972). Shamanism. Archaic Techniques of Ectasy. pp. 3–7. In: Bolligen Series LXXVI. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Evans Pritchard, E.E. (1956). Nuer Religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Findly, E.B. (2008). Plant Lives: Borderline Beings in Indian Traditions. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Gadgil, M. (1987). Diversity: Cultural and Biological. TREE 2, 369–373.

Gadgil, M. & Thapar, R. (1990). Human Ecology in India. Some Historical Perspectives. Interdisciplinary Sci. Rev. 15, 209–223.

Hopfe, M. & Woodward, R. (1998). Religious of the World. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Kalyanam, G. (1970). Sivalayam Ratnagiri Thalavaralaru (in Tamil). Ratnagiri, Tamil Nadu, India.

Kane, P.V. (1990–1991). History of Dharmasastra. Vols. 1–5. (Revised and enlarged edition). Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona.

Kosambi, D.D. (1962). Myth and Reality: Studies in the Formation of Indian Culture. Bombay: Popular Press.

Krishnamurthy, K.V. (2003). Text Book of Biodiversity. Enfield (NH), USA: Science Publishers.

Krishnamurthy, K.V. (2005). History of Science. Tiruchirappalli, India: Bharathidasan University Publications.

Krishnamurthy, K.V. (2007). Tamilarum Thavaramum (in Tamil). 2nd Edition. Tiruchirappalli, India: Bharathidasan University Publications.

Nabokov, I. (2000). Religion Against the Self: An Ethnography of Tamil Rituals. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Paramasivam, T. (2001). Panpattu Asaivugal (in Tamil). Nagercoil, India: Kalachuvadu Publications.

Parthasarathy, J. (2002). Tribal People and Eastern Ghats: An Anthropological Perspective on Mountains and Indigenous Cultures in Tamil Nadu. pp. 442–450. In: Proc. Nat. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad.

Pushpangadan, P. & Pradeep, P.R.J. (2008). A Glimpse at Tribal India—An Ethnobiological Enquiry. Thiruvanandapuram: Amity.

Radhakrishnan, S. (1993). The Principal Upanisads. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Rajan, K. (2004). Tholliyal Nokkil Sangakalam (in Tamil). Chennai: International Institute of Tamil Studies.

Salas, M.A. (1994). “The Technicians only believe in science and cannot read the sky.” The cultural dimension of the knowledge conflict in the Andes. pp. 57–69. In: I. Scoones & Thompson, J. (Eds.). Beyond Farmer First: Rural People’s Knowledge, Research and Extension Practice. London: Intermediate Technology Publications.

Subramanian, N. (1996). The Tamils. Institute of Asian Studies, Chennai.

Sundara Sobitharaj, K.K. (1994). Thala Marangal (in Tamil). Sobitham, Chennai.

Swamy, B.G.L. (1978). Sources for a History of Plant Sciences in India. IV. “Temple Plants” (Sthala-Vŗksas)—A Reconnaissance. Trans. Arch. Soc. S. India.

Thaninayagam, X.S. (2011). The Educators of Early Tamil Society pp. 181–196. In: Sivaganesh, D. (Ed.). The Collected Papers on Classical Tamil Literature in the Journal of Tamil Culture. Chennai: New Century Book House (P) Ltd.

Tylor, S.B. (1874). Primitive Culture. New York.

Varadarajan, M. (1965). The Treatment of Nature in Sangam Literature. Second Edition. Tirunelveli Saiva Siddhanta Nool Pathippagam, Chennai.

Witehead, H. (1921). The Village Gods of India. Madras: Oxford University Press.

Zimmer, H. (1935). The Art of Indian Asia. New York: Pantheon Books.