CHAPTER 10

CONSERVATION, DOCUMENTATION AND MANAGEMENT OF ETHNIC COMMUNITIES OF EASTERN GHATS AND ADJACENT DECCAN REGION AND THEIR PLANT KNOWLEDGE

K. V. KRISHNAMURTHY,1 BIR BAHADUR,2 RAZIA SULTANA,3 and S. JOHN ADAMS4

1Department of Plant Science, Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli–620024, India

2Department of Botany, Kakatiya University, Warangal–506009, India

3EPTRI, Gachibowli, Hyderabad–500032, India

4Department of Pharmacognosy, R&D, The Himalaya Drug Company, Makali, Bangalore, India

CONTENTS

10.5Bioprospecting and Biopiracy

ABSTRACT

This chapter briefly summarizes the efforts so far made in the conservation, documentation and management of ethnic tribes of Eastern Ghats and the adjacent Deccan region and their ethnobotanical knowledge. Conservation efforts made by tribes themselves (like recognition of sacred temple trees and sacred groves) as well as by governmental and non-governmental organizations and institutions are detailed. Attempts made on conservation at the genetic, species and ecosystem levels involving in situ and ex situ approaches are also highlighted. Documentation efforts on traditional knowledge system as well as management details are provided. The importance of endogenous development to protect tribals and their knowledge is stressed

10.1INTRODUCTION

‘Conservation’ implies the protection of environmental resources for sustainable utilization (Krishnamurthy, 2003). According to the modern concept of conservation, all these resources, whether used or not at present, should be protected. There is an ever-growing demand for these resources. Essentially three methods have been employed in the choice and use of botanical resources: (i) random method, which employs random collection of a plant for testing its value and use; (ii) phylogenetic method, which involves collection and testing of a plant whose close relatives have already been found to have some use or value; and (iii) ethno-directed method, in which attention is particularly focused on a plant whose value and use are already known to and tested by traditional ethnic communities; it is a readymade knowledge that is sure to yield the desired result, in addition to involving less research, development cost and time. In view of the above, it is all the more very vital to protect and conserve tribals, their habitats, their knowledge on useful plants and the plants themselves.

Sectorial approaches to conservation and management of traditional plant resources made sense when trade-offs among goods and services were local, more modest or unimportant. They are not sufficient today when conservation and management of services and goods have to meet conflicting goals. Hence, we are now forced to follow an integrated approach conservation and management of traditional plants. Successful conservation and management of traditional plant resources depend on two very important factors (Krishnamurthy, 2003): (i) The social, cultural, economic and political contexts of traditional societies within which management objectives are pursued; and (ii) Proper tools and methods that are to be selected to attain the aforesaid objectives. An integrated, predictive and adaptive approach to traditional phytodiversity management requires three basic types of information: (i) reliable site-specific baseline information on all aspects of plant knowledge of different ethnic societies and their documentation; (ii) knowledge on how goods and services offered by plants in specific ethnic communities will change to changing times and environments; and (iii) integrated local models that incorporate the traditional methods that incorporate traditional values, visions, need and priorities, as well as endogenous developmental changes (see later for more details). Management of ethnic botanical knowledge should also be brought about effectively through committed organizations and institutions (both governmental and non-governmental) functioning at the local, regional, national and international levels. These are required to frame policies and methodologies for execution of all conserva-tional and managerial activities. They should also collect/collate vital data, store them and distribute them to the needy.

This chapter deals with conservation, documentation and management of ethnobotanical knowledge (in terms of both goods and services) of Eastern Ghats (E. Ghats) and adjacent Deccan region (see also Rawat, 1997; Henry Jonathan and Solomon Raju, 2007). There will be some overlap in the account given below since the three aspects mentioned above are intimately related to one another.

10.2CONSERVATION

Conservation of ethnobotanical knowledge and plants in the study region has been attempted at three levels of plant biodiversity: genetic, species and ecosystem. Conservation at any one level automatically has helped in the conservation at the other two levels.

10.2.1CONSERVATION OF GENETIC DIVERSITY

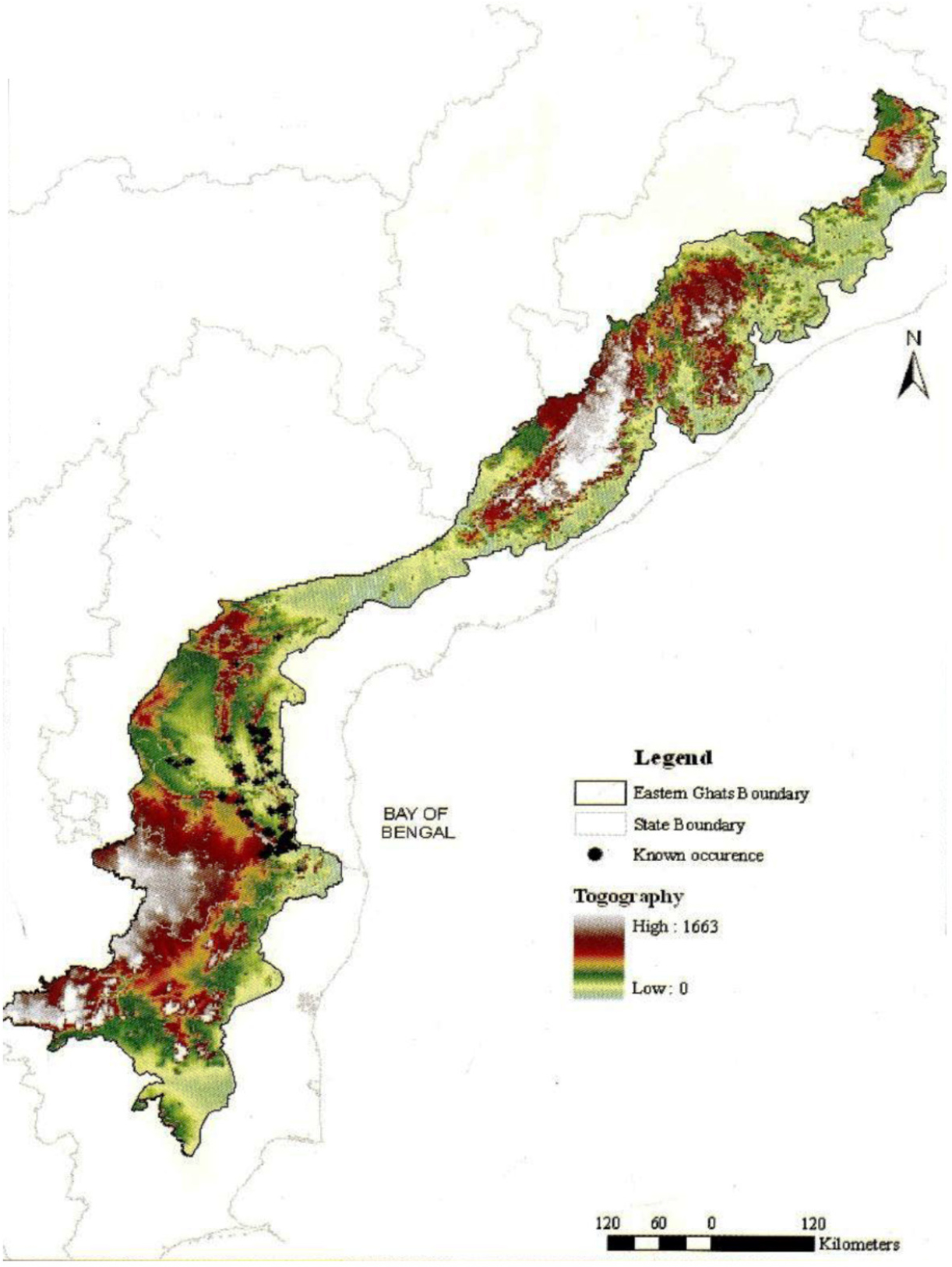

Conservation of genetic diversity has been planned and executed at the population level, since population is the basic unit at which genetic diversity is usually assessed. Three types of studies have been carried out on the ethnobotanical genetic diversity of the study region. The first one relates to the assessment of genetic diversity of important plant species whose populations have been collected from different provenances. This has provided the baseline data to focus conservation priority attention on the provenance showing the maximum genetic diversity as assessed through various molecular biology techniques. The second type of study relates to the estimation of minimum viable population size (MVP size) through population size estimation and population viability analysis (PVA) (see Krishnamurthy, 2003; 2012). Sridhar Reddy and Ravi Prasad Rao (2007) and Giriraj et al. (2007), for example, have made detailed observations on the distribution and population structure of Pterocarpus santalinus, a narrow endemic and endangered tree of E. Ghats in Kadapa (Cuddapah) hill ranges of Andhra Pradesh (Figure 10.1). The bark is used by local tribals for diarrhea and snake bite, while the wood is used to cure rheumatism, diabetes, inflammation from cuts and bleeding piles. The above authors have recorded just a very few individual trees of this species and the populations are mapped. Similarly, the distribution of Cycas beddomei, a critically endangered and endemic species, has been studied by Suresh Babu et al. (2007) although critical population assessments have not been made. The third type of study relates to the collection and characterization of subspecific taxa of ethnically important species, particularly land races and their relatives (Pandravada et al., 2008) and farmers varieties. On-farm and home garden conservation methodologies are being followed by some ethnic communities as well as by non-governmental organization in the tribal localities of the region studied here. The crop varieties maintained on-farm are often landraces, which are highly adapted to the local environmental conditions and invariably contain locally-adapted alleles that have been proved to be useful for specific breeding programs. Although landraces yield much less modern cultivars, they are so ancient and valuable that it is worth conserving them for posterity; they also need to be continuously monitored. For example, Pandravada et al. (2007) have suggested the landraces for some agriculturally important species and other species and pockets for on-form and in situ conservation. These include Orzya officinalis subsp. malampuzhaensis (in Nallamalai hills in Andhra Pradesh), O. jeyporensis (in Koraput in Odisha), Cajanus cajanifolius (in Visakhapatnam of Andhra Pradesh and Gajapati in Odisha), Solanum erianthum, and Luffa acutangula var. amara (both in Rayalaseema region of Andhra Pradesh), Curcuma aromatica and Mango varities (in Visakhapatnam), Ensete glaucum and Musa ornata (in Visakhapatanam and East Godhavari), Cycas beddomei (in Chittoor), Pimpinella tirupatiensis (in Tirupati), Minor millets (in Visakhapatnam), and Okra (in Adilabad)

FIGURE 10.1Locations of Pterocarpus santalinus, an endemic and endangered tree (Murthy et al. 2007a). (Murthy et al. 2007a; used with permission from EPTRI).

Home garden conservation is a small-level conservation effort by traditional societies. Many ethnic societies of the study region grow those plant germplasms that are needed for their use at home, kitchen or backyard gardens. Hundreds of such gardens exist in the tribal belts of all the five states through which E. Ghats run. Most of these are taxa that are either vegetables/fruits or medicinal plants; some of them are also ornamentals. These germplasms are often indigenous in the form of landraces, obsolete cultivars or rare species.

Some germplasm collections are assemblages of genotypes, populations or provenance collections that are often maintained as research materials for plant breeders and phytopathologists. They may consist of samples of domesticated plants and their wild relatives. These germplasms are maintained either in vivo in the form of plants, seeds, tubers or other propagates or in vitro in the form of single cells, embryos, buds or synseeds. There are different types of institutions involved in germplasm collections, which are called accessions (both core accessions and reserve accessions). Some of these institutions are treated subsequently in this chapter. A seed bank is a collection of seeds stored in a viable state for posterity. It is a good device for ex situ conservation of germplasms of sexually reproducing plants.

10.2.2CONSERVATION OF SPECIES DIVERSITY

It is well-known that species is the main player in conservation conceptually, biologically and legally (Meffe and Carroll, 1994). It is because loss of species diversity is very obvious, more easily detectable and quantifiable than loss of either genetic or ecosystem diversity. The first effort in the conservation of species diversity in the study region involved the identification of those species that are in the IUCN threat list under its various categories: extinct in the wild, critically endangered, endangered, vulnerable and rare. Around 320 such taxa have been listed in Krishnamurthy et al. (2014). Biswal and Sudhakar Reddy (2007) have enlisted 127 such taxa for Odisha State. The most important threatened taxa need priority attention for conservation measures with attendant status studies on their population size, MVP size and reproductive biology. Although some attempts have been made to study the reproductive biology of some taxa belonging to E. Ghats (Sivaraj, 1991; Sivaraj and Krishnamurthy, 1989, 1992, 2002, Sivaraj et al., 2007; Solomon Raju, 2007; Solomon Raju and Henry Jonathan, 2010; Solomon Raju and Purnachandra Rao, 2002a, b; Solomon Raju et al., 2002, 2003, 2004, 2009), attention has not been focused on threatened taxa. Although effective traditional conservation measures are already in practice, more recent in situ and ex situ conservation strategies have also been taken up for execution. Both wild and domesticated taxa have been conserved by in situ methods, while ex situ methods primarily involve wild taxa and wild relatives of cultivated taxa.

One of the ways in which traditional ethnic communities of the study region had protected and conserved particular plant species was by assigning them to be the sthalavrksha (=temple trees). The plant species are specific to each temple and are considered as dear to the presiding deity of the concerned temple. The local ethnic community automatically considered these tree species as sacred and did not harm them wherever they are found (Krishnamurthy et al., 2014). Detailed accounts on temple plants are already given in Chapter 3.

10.2.3CONSERVATION OF ECOSYSTEM DIVERSITY

In this method (which is the cheapest and most effective method), certain areas of ecosystems or important habitats are protected and maintained through various kinds of protected area programs or through controlled land use strategies. Invariably such areas are decided/selected by criteria, such as species richness, degree of endemism and threat index for wild taxa and land race diversity and wild relative abundance for domesticated taxa. Also taken into consideration are areas rich in tribals and in ethnic botanical knowledge. Ecosystem conservation not only protects species and their genetic diversity but also the various ecosystem services. As in species conservation efforts, here also ecosystems that need priority attention for conservation are to be given the greatest and immediate action.

Many fragile ecosystems/habitats in E. Ghats have already been identified both through extensive field studies and remote sensing and GIS technologies. Rao (1998) proposed the establishment of Biosphere reserves (see later for details on biosphere reserves) in (i) Similipal, Jeypore, Mahendragiri, and Malkangiri hill areas of Odisha; (ii) Dandakaranya forests of Koraput in Odisha; (iii) Thanjavanam-Lumbasingi-Tanjangi area of Visakhapatnam and E. Godavari districts of Andhra Pradesh; (iv) Gudem-Sapparla-Dhanukonda-Rampa-Maredumalli areas of Visakhapatnam and E. Godavari district; (v) Papi hills-Bhadrachalam areas of W. Godavari district; (vi) Nallamalai (Gundlabrahmeswaram-Ahobilam)-Seshachalem-Tirupati hills in Southern Andhra Pradesh; (vii) Shevaroy hills (Salem-Dhamapuri districts); (Viii) BR hills (near Mysore in Karnataka); and (ix) Sandur hills (in Bellary). Venkaiah (1998) also suggested the formation of Biosphere Reserves for the sal forest area near Rella, Manda and Peddakonda (all under Salur forest area) and Duggeru, Kurukutti and Thonam forests under Kurupam forest are. Sastry (2002) suggested the formation of Natural parks/wildlife sanctuaries/Reserve forests at Similipal, Jeypore, Mahendragiri, Malkangiri, Dandakaranya, Thanjavanam-Lumbasingi-Tanjangi, Gudem-Sapparla-Dharakonda-Rampa-Maredumilli, Papi-Bhadrachalam hills, Nallamalais-Seshachalam, -Tirupati hills (in Andhra Pradesh), Shervaroys (in Tamil Nadu) and Sandur and B.R. Hills (both in Karnataka). Sudhakar Reddy et al. (2007a, b) suggested the conservation of Mahendragiri (Gajapati district), Konda Kamuru and Upper Sileru (Malkangiri district), Deomali and Gupteshwar (Koraput district), Berbera (Khurda district), Niyamgiri hills (Royagada district), Kalinga Ghat and Ranipathar (Phulbani district) and Kapilas and Saptasajya (Dhenkanal district) based on detailed geospatial data and field studies. Murthy et al. (2007b), based on remote sensing and GIS data on the entire E. Ghats have identified the following nine conservation priority contiguous areas based on biological richness value of Sections 10.1–10.4 of E. Ghats (see Chapter 1 and for more details see Krishnamurthy et al., 2014); (i) Similipal-Hadgarh-Kuldiha (ii) Berbera (iii) Phulbani-Karlapat-Niyamgiri-Baisipalli (iv) Lakhari valley (v) Kondakamberu-Sileru-Upper Visakha (vi) Kalrayan hills (viii) Kolli hills and (ix) BR hills. Murthy et al. (2007b) added Shervaroy hills to the above list. Britto and his students have identified conservation priority zones within the following hills: Shervaroys (Balaguru et al., 2006), Pachaimalais (Soosairaj et al., 2007) and Chitteri (Natarajan et al., 2004).

Ganeshaiah and Uma Shaanker (1998) have suggested a national approach to prioritize conservation of plants/vegetation through a hierarchical integration of the biological and spatial elements of conservation. This approach should seek to independently map these elements of conservation and then to integrate them to arrive at country-wide maps for conservation, for example, contous of Conservation. A good illustration is the mapping of the distribution of Pterocarpus santalinus, a threatened narrow endemic plants species of E. Ghats (Giriraj et al. 2007). In continuation of this suggestion the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India in association with the department of space and under the auspices of National Bioresources Development Board has launched two national level programs: (i) Landscape level mapping of biodiversity of the country and its characterization using satellite remote sensing and geographic information system, during the period 1998–2010 and (ii) Inventorying and mapping bioresources. Both these programs covered the region studied in this volume. The major highlights of the first program were as follows: (i) it provided a first ever baseline biodiversity database; (ii) it gave information on vegetation types, disturbance regimes therein, biological richness, fragmentation and non-spatial database on phytosociology; (ii) it provided GPS-tagged species archives. The entire database is in the public domain and can be used by anyone interested (http://bis.iirs.govt.in). The second program included bioresource inventorying of E. Ghats. The entire stretch of E. Ghats was stratified into 2652 grids of 6.36 x 6.36 km2 and the plant populations recorded in each grid in 2–4 transects of 1,000 x 5 m2 size. Among the results obtained the most significant are the recording of 168 endemics (up to peninsular India level) and 28 threatened taxa; 74 taxa were recommended for inclusion in the red lists; 870 economically important species were recorded (486 medicinal, 144 edible, 98 fodder, 67 timber and 100 wild ornamental plant species).

Based on several indices a number of National Agricultural Heritage sites were identified for priority conservation in the high altitude tribal areas of Northern undivided Andhra Pradesh and Odisha (Singh and Varaprasad 2008; see also Krishnamurthy et al. 2014).

The following categories of important protected areas have already been established in the study region for the conservation of ethnic communities and their ethnobotanical resources: (i) Biosphere Resources: 18 biosphere reserves are recognized in India, two of which occur in the study region, the Similipal Biosphere Reserve (in Odisha) and Seshachalam hills (in Andhra Pradesh). (ii) Wildlife Sanctuaries: 498 wildlife sanctuaries have been established in India of which many occur in E. Ghats. The most important in Odisha occur in Badrama, Khalasundi, Hadgarh, Karlapet, Kotagarh, Lakhari valley, Sunabeda, Satkosia and Bhitarkanika. The most important in the undivided Andhra Pradesh are Etunagaram, Nagarjunasagar-Srisailam, Gundla Brahmeshwaram Metta, Salur, Sri Lankamalleswaram, Nelapattu, Rollapadu, Koringa, Kawal, Kolleru, Papikonda, Lanjamadugu, Kambalkonda, Krishna, Koundinya, Sri Lankamalleswara and Pranahita. Wildlife sancharies also exist in BR hills of Karnataka and Vedanthangal of Tamil Nadu. (iii) National parks: 92 national parks are known in India of which two occur in Odisha, four in undivided Andhra Pradesh and two in Tamil Nadu. (iv) Centre of Plant Diversity (CPD): Of the 234 CPDs recognized by IUCN in the world (up to 1998) 13 occur in India; three of these are in the study region (Nallamalais, Tirupati-Cuddapah hills and Northern Cicars. (v) Several hundreds of Reserve forests have been established throughout E. Ghats. (vi) Medicinal Plant Conservation Areas (MPCAs): these areas were identified and established by the Foundation for the Revitalization of Local Health Traditions (FRLHT), a Bangalore-based NGO in cooperation with State Forest Departments, based on wild Medicinal Plant wealth that needs conservation (Noorunnisa Begum et al., 2004). A total 55 MPCAs were established (12 in Tamil Nadu, 13 in Karnataka, 8 in undivided Andhra Pradesh, 5 in Odisha and the rest in a few other states of India). Of these, 21 are located in the study region. A number of wild medicinal plants used in folk and tribal medicine were thus conserved by these MPCAs in the wild.

Although the establishment of the above-mentioned types of protected areas is a fairly recent one in many places of the world, dating back only to about a century, the concept itself is really several centuries old (Kosambi, 1962) in India and some other parts of the world (Hughes and Chandran, 1998). There are both traditional and more recently established protected areas, since losses as well as conservation of plants have been issues of great intrinsic social and cultural concerns for the ethnic people (Shiva et al., 1991). Society and social, cultural and religion values have been called in to conserve nature and bioresources around them through sacred groves. The groves have been dedicated to the worship of the presiding deities of the concerned temples and are considered as the properties of those deities, which may be male or female. The deities are represented in the temple as a slab stone, a hero stone, Sati stone, or a trident, but rarely as idols. Even idols are there, they have been introduced quite late in the history of the sacred groves. Since great sanctity has been ascribed to the plants of such groves in the study area and since spiritual beings have been believed to reside in the groves, ordinary human activities are voluntarily precluded and several taboos and belief systems are associated with them. These activities included tree-felling, gathering of wood/fuel; plants, leaves, flowers, fruits and seeds, grazing by domestic animals, plowing, planting and harvesting, and dwelling (see full literature in Krishnamurthy et al., 2014). These ensured the conservation and preservation of the vegetation of sacred groves for posterity. In India, although there may be around 1,00,000 sacred groves (Swain et al., 2008), Henry Jonathan (2008) reported around 14,000 groves. According to Malhotra et al. (2001) there are 13,720 sacred groves of various sizes, diverse floristic composition and different vegetation types. Local autonomy is being given to these groves. The temple priest (who is also often the village doctor) is the only person authorized to enter the groves and that too for sustainably collecting plants/plant parts for worshipping the deity or for medicinal purposes (Krishnamurthy, 2003). There are 322 sacred groves in Odisha, 750 in undivided Andhra Pradesh, 488 in Tamil Nadu and around 75 in the E. Ghats region of Karnataka.

10.3DOCUMENTATION

There is an enormous amount of knowledge among the ethnic tribal communities on the cultural and utilitarian uses and values of plants around them, most of which are not recorded and codified. Unfortunately, many knowledgeable tribal people have died either without divulging their knowledge on traditionally used plants or refused to part with them for reasons best known to them. This has resulted in the absence/scarcity of records on indigenous knowledge on plants. Thus, the collection and documentation of ethnobotanical data, information, knowledge and wisdom are very vital. The use of the same is often triggered by three principal categories of motivation (Krishnamurthy, 2003): (i) public policy; (ii) private sector and public interest; and (iii) culture. Documentation involves the following steps: data collection, storage of data, analysis of organized and integrated data so as to obtain useful and pertinent information, derivation of knowledge from such information through further analysis, interpretation and finally taking wise, proper and efficient management initiatives or actions through intelligent use of such knowledge.

Bibliographies related to ethnic botanical knowledge on the various ethnic communities of study region provide basic information on biology, forestry, agriculture, wildlife, conservation, food, medicine, society, culture, ethnic laws, economics and politics. These are available as published literature in journals, periodicals, books, and gray literature, such as reports, unpublished theses, manuscripts, etc. There are research papers on specific human and animal disease and the plants used by ethnic communities of the study region for both preventive and curative effects on these diseases. Most important research papers are mentioned in Chapters 7 and 8 of this volume. There are research papers on specific tribal groups of the study region and their knowledge on plants of value and use. Many of these are cited in various chapters of this volume. Research papers have also been published on the traditional botanical knowledge of different parts of the study region, like for example, Odisha, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka or in different hill ranges of these states. Yet other research papers cover specific ethnic plant taxa (i.e., of particular families, genera or species). The authors of all these research papers hail from several official agencies, institutions, universities, colleges, research centers and non-governmental organizations. Several periodicals/journals have published valuable data/information on the diverse ethnic tribes of E. Ghats and the adjacent Deccan region. Journals/periodicals that have published information on the ethnobotany of the study region are either general journals or are journals that are specifically related to ethnobotany or traditional knowledge. Most important among the latter are Indian Journal of Traditional knowledge, Asian Journal of Traditional knowledge, Journal of Economic and Taxonomic Botany, Ethnobotany, Ancient Science of Life, etc. The validation of the efficacy of traditional medicinal plants and their chemical constituents have been the subject of research papers that are being published in journals related to pharmacy, pharmacology, medicinal plants, phytochemistry, and traditional, alternate and complementary medicine, etc.

There are more than 50 books, which deal with the ethnobotany of the various traditional communities of the study region. The most important books that contain information on the ethnic tribes and their ethnobotanical knowledge on the study region are enlisted in Krishnamurthy et al. (2014). The most important gray literature relates to PhD theses from leading universities and research institutions of the study region. More than 120 PhD theses have been submitted on the ethnobotany of the various ethnic tribes/communities. Special mention must be made of the Society of Ethnobotanists, which was first established by S.K. Jain in 1980 with headquarters at the National Botanical Research Institute in Lucknow. This society has not only brought together all ethnobotanists of India but also encouraged various ethnobotanical researchers and activities. It has organized various kinds of meets and interactions between ethnobotanists. As examples of such meets can be mentioned the following: (i) Ethnobiology in Human Welfare held in November 1994 at Lucknow; it is the proceedings of this IV International Conference on Ethnobiology. It was edited by Dr. S.K. Jain and published by Deep Publications; (ii) National Workshop on Ethnobiology and Tribal Welfare organized at Coimbatore by AICRPE in Nov. 1985; (iii) National Conference on Traditional Knowledge ‘Dhikshana 2008’ in May 2008 at Thiruvananthapuram; (iv) the various seminars organized by EPTRI, Hyderabad on the conservation of Eastern Ghats; (v) The various conferences so far organized by the India Association for Angiosperm Taxonomy, India.

The most important effort towards documentation of ethnobotanical knowledge was made in 1982. The Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), Government of India launched in 1982 the All India Co-ordinated Research Project on Ethnobiology (AICRPE). It is a multidisciplinary and multiinstitutional project involving more than 500 scientists and 27 institutions. The report of this project was submitted in 1994. It records around 10,000 medicinal plant species of which about 8,000 are wild plants. The report covers 550 tribal communities with 83.3 million people. It reports 3,900 edible wild plants, 400 fodder species, and 300 plant pesticides.

Databases form an important source of ethnobotanical data. ‘Data’ refer to “observation, measurements or facts referenced to some kind of accepted standard, which are subsequently integrated, processed, interpreted or otherwise manipulated to produce information.” ‘Information” refers to the “knowledge (product) derived from the analysis and interpretation of data” (Busby, 1997). Such data are stored, managed and readily made available for integration with other data. The absolute need for effective organization, management and use of data and information on ethnic plants is already reflected in many national and international agreements, legislations, and policy decisions, such as CBD, CITES, UNICEF, UNEP, etc. (see details in Krishnamurthy, 2003). The Biodiversity Data Management (BDM) is one such important outcome (see ‘BDM UPDATE’ Newsletter for relevant issues and events). The Taxonomic Databases Working Group for Plant Sciences SA 2000 and other Taxonomy Databases are another important result of this effort. For a list of Databases see Krishnamurthy (2003). The most important Databases that provide data on the ethnobotany of the study region are managed and operated by specific organizations and institutions, as detailed subsequently in this chapter. In addition, there are also Special Interest Networks, Traditional Biodiversity Application softwares, CD-ROMs and Diskettes. There are also catalogs and indexes of plant taxa known to the ethnic tribes of the study region.

The Community Biodiversity Registers (CBRs) form a ‘bottoms-up system’ of recorded data/information on wild and domesticated ethnodiversity in India (Gadgil et al., 1995). This is an important effort to secure community control over IKS. People of indigenous societies are encouraged to document all the known plant (and animal) species, with all available details on their uses. CBRs contain four separate sections: (i) Background information with two modules. Module 1 covers the total land/aquatic area, settlements and human communities, while module 2 covers the detailed local ecological history of the place; (ii) Practical ecological knowledge that is collected through critical surveys and then documented. Biodiversity status and utilization details are collected and recorded; (iii) Claims of local people relate to information provided by the local people regarding properties used and processes relating to bioresources; this is done even if such uses and properties have not yet been provided; (iv) Scientific Knowledge provided by the local people regarding biodiversity elements are documented. Ideally each village/traditional community should have one CBR and the preparation of the same should involve one or more local educational institutions of that area. All members outside that particular village/community are then refused normal access to the details contained in the CBR, but may be allowed on certain specific conditions. CBRs have been prepared for several villages/communities in India, including those in the study area covered by this volume.

One of the methods of documentation of ethnobotanical knowledge is the deposition of traditional plant-based materials in specially designed museums and culture collections. Although modern ethnobotany, especially of western countries, has a clear agenda centered on plant use (Cornish and Nesbitt, 2014), many traditional societies of the old world still emphasize the cultural and cognitive social approaches to the use of plants around them. Ethnobotanical knowledge, hence, should not reside only in memory, in books, manuscripts and photographs, in botanic gardens and in herbarium specimens. The focus should also be on ethnobotancial specimen collections as they form a rich source of data for contemporary ethnobotanists but also are fundamental to understanding the evolution of ethnobotany as a discipline (Cornish and Nesbitt, 2014). Such specimens have a long history and are highly effective in conveying knowledge, not only of the plant part used but also of the way in which it is processed. Ethnobotanial specimens are collected and kept in many locations in the world but specimens related to E. Ghats and the adjacent Deccan region are kept in the Economic Botany collection in Indian Museum, Kolkata, and in the Biocultural Collection Centre of Foundation for the Revitalization of Local Health Traditions (FRLHT), Bangalore. Some specimens are also kept at the Chennai Museum and the Museum of Economic Botany, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

10.4MANAGEMENT

There is an urgent need for resonance between the needs of ethnobotany and scientists on the one hand and the necessary data and information on traditional knowledge of ethnic communities on the other. In Section 10.3, the importance of collection and documentation of ethnic botanical knowledge was emphasized; also, the various kinds of documentation were discussed. The collection, documentation and distribution of these data and information are done by organizations and institutions, as mentioned earlier, in order to make effective decisions on managing the traditional plant resources and to implement these decisions.

The management of ethnobotanical knowledge in the study region was done through a number of organizations, both governmental and non-governmental. The governmental organization (both Central and State-controlled) are primarily concerned with framing laws, rules, legislations, policies and implementation methodologies for execution of conservation actions besides serving as sources of data on ethnobotany. The non-governmental organizations are involved in documentation and dissemination of data/information besides executing, on their own, conservation and management of ethnic knowledge, but under the overall control of the government.

Ethnic knowledge on plants of India, including the region studied in this volume, is managed by the following important Information Networks (see for more details Chavan and Chandramohan, 1995; Geevan, 1995): (i) Foundation for the Revitalization of Local health Traditions (FRLHT), which houses the Indian Medicinal Plants National Network of Distributed Database (INMEDPLAN) of traditional medicinal plants; (ii) Biotechnology Information System (BTIS) consisting of the Distributed Information Centres of the Department of Biotechnoliogy supported by NICNET, the computer network of the National Informatics Centre (NIC); (iii) The Indian Bioresource Information Network (IBIN) (www.ibin.co.in) is a distributed database on bio-resources and biodiversity. The Bioresources information Centres situated all over the country collaborate with IBIN. Jeeva Sampada is a database on Bioresources of India and it provides data on 39,000 species of plants, animals, marine organisms and microbes and comprises of more than 54,00,000 records. It also offers images, distribution maps and uses in an interactive data retrieval service (see for more details the booklet entitled Indian Bioresource information Network, Published by the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. (iv) MEDLARS, the Medicinal Literature Analysis and Retrieval System, accessible over NICNET; (v) Biodiversity Information System (BIS) of the Indira Gandhi Conservation Monitoring Centre (IGCMC) established by the WWF and the Environmental Resources Information System (ERIS); (vi) ENVIS (Environmental Information System) India supported by the Ministry of Environment and Forests of Government of India; (vii) NBPGR (National Bureau of Plant Genetic resources) databases located at New Delhi and Hyderabad. NBPGR has the following mandates: Characterization, Evaluation, Documentation, Conservation and Bioprospecting. Collection related to the ethnobotany of the study region is deposited in NBPGR’s National Gene Bank; there is also a National Herbarium of Cultivated Plants. The Botanical Survey of India also has collections of wild plants of the study region, including those used by the ethnic societies of this region. (vii) The people and plants website, an initiative of the partnership between WWF and UNESCO with the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew taking an associate role.

10.4.1MANAGEMENT ORGANIZATIONS AND EFFORTS

The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), a federative membership organization composed essentially of governments or governmental organizations of the various countries of the world as well as scientific professional and conservation organizations, has helped and advised in the identification and preparation of a list of threatened categories plants (Red List) of India, including those of the study region. UNESCO (United National Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), through its Man and Biosphere Programme (MAB), has been instrumental in the establishment of protective areas in India, including those in the study area (see an earlier page of this chapter for details). It has also established cultural heritage sites. Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) has helped in the conservation of genetic resources of food plants through its Global System for Conservation of Plant Genetic Resources and Commission on Plant Genetic Resources (PGR).

The M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF) located in Chennai has carried out a project, under Indo-Canada Environment Facility, on “Coastal Wetlands: Mangroves Conservation and Management.” Under this project, 14 demonstration villages falling in the East Coast Mangrove belt were targeted but only in 24 villages it was implemented. The villages were involved in the restoration of mangrove forests under their jurisdiction. The MSSRF has also established several field sites in the study region. Two of these are very important: Kolli hills in Tamil Nadu and Jeypore in Odisha. These two are involved in community-based agrobiodiversity conservation programs. The major activities are revitalization of traditional conservation, participatory plant improvement actions, and establishment of databases (Uma Ramachandran, 2002). Experts available in these two sites have formed networks with all stakeholders. After correctly identifying the resource base in these two regions and the associated problems, these are addressed through participatory meetings and training activities to strengthen their participation. This organization is also involved in in situ/on-form conservation of agrobiodiversity involving community seed and grain banks. In these banks seeds of traditional land races are maintained by self-help groups. These banks are linked to the Scarascia Mugnozza Community Genetic Resources Centre located at MSSRF in Chennai. The very important tribal seed banks are located in Kolli hills (Tamil Nadu where the Malayali tribes are involved by MSSRF to maintain landraces of minor millets and some legumes) and in Jeypore (Odisha) where the local tribals are involved in maintaining landraces of rice as well as its wild relatives

The Centre for Farmers’ Rights at MSSRF deals with “the rights arising from the past, present and future contributions of farmers in conserving, improving and making available plant genetic resources” (Swaminathan, 1997). The concept of Farmers’ Rights aims at benefit–sharing through a process of compensation for the use of TKS, in contrast to the system of Internalization of benefits . A Charter of Rights is included and some of them are mentioned by Shiva and Ramprasad (1993). A Resource Centre for Farmers’ Rights has been formed by MSSRF in order to involve in the following four activities: (i) Farmers’ Rights Information Service (FRIS) with a collection of several component databases, such as IPR database (with four modules respectively dealing with tribal contributions, ethnobotanical features, sacred groves, and rare angiosperms) and multimedia database on the ecological farmers of India; (ii) Community Gene Bank, meant for storing seeds of landraces, traditional cultivars and folk varieties; (iii) Community Genetic Resources Herbarium, meant to serve as a reference center for the identification of rare and threatened plants, economically important plants and traditional culti-vars; and (iv) Agrobiodiversity Conservation Crops created to train young tribal and rural men and women in conservation techniques and seed science and technology.

The Environmental Protection, Training and Research Institute (EPTRI), located at Hyderabad, is one of the 25 centers established by Government of India in 1994 to protect environmental resources, particularly of ethnic communities. These centers are supported by Ministry of Environment and Forests, New Delhi under its Action Oriented Research Program for the collection, storage and dissemination of data and information. These centers are called ENVIS centers, which are centralized Networks that bring about coordination between institutions and organization. The EPTRI is meant for E. Ghats and brings about a Newsletter on E. Ghats. EPTRI has a database called EPTRI Information System, which integrates various thematic and attribute data. This is very useful for various conservation and developmental projects. It has designed, developed and updated the database on bibliography, experts, and environmental resources (flora, fauna, microbes, water, soil, geology, tribals, traditional knowledge, etc.) pertaining to E. Ghats (Srinivasa Rao, 2007). The Resource Database is designed based on UNDP Global Information Database format. This database has about 1,500 parameters. EPTRI-ENVIS is regularly conducting seminars on E. Ghats and publish their proceedings.

There are several other NGOs/organizations involved in the management of TKS/tribals of the study region. In Nallamalais 10 NGOs have been working under Abhayaranya Samrakshan through Holistic Resource (Array) Management (ASHRAM). The Anantha Paryavarana Parirakshana Samithi in Anantapur, Regional Plant Resource Centre at Bhubaneswar, the Odisha State Vanaspati Vana Society at Cuttack, the Save Eastern Ghats Organization at Chengam in Javadi hills, the Centre for Indian knowledge studies at Chennai, etc. are involved in documenting and managing tribal ethnobotanical knowledge of the study region. The Centre of Indian Knowledge System located at Chennai has been undertaking a large number of grassroot level efforts for the on-farm conservation of indigenous genetic resources, organic agriculture, integrated home gardens and Vrksāyurveda (ancient Indian Plant Science). Run by A.V. Balasubramanian and K.V. Vijayalakshmi, this organization has been working for the last 18 years, through field studies, on indigenous rice varieties of Tamil Nadu and adjacent regions. The organization has also helped in the establishment of Farmer’s Seed Banks for seed exchange, distribution and utilization, as well as in conducting training and outreach programme’s for villagers/tribals.

The Deccan Development Society (DDS) is a grassroot level organization in the Medak district of Telangana. It has adopted about 75 villages where it works with women’s groups. DDS works for food security and food sovereignty for the rural people.

Another organization that manages ethnobotanical data, facilitated their use and exchange and raises important issues on TKS in India is the Society for Research and Initiatives for Sustainable Technologies and Institutions (SRISTI) initiated by Professor Anil Gupta of the Indian Institute of Management at Ahmedabad. SRISTI has already established communications with more than 300 villages of India with the main objective of capacity building at grassroot level in biodiversity conservation, protecting TKS, endogenous development (see later in this chapter for more details) and enrichment of the cultural and institution base of ethnic communities. SRISTI also provides legal counseling with reference to the protection of TKS. It has also established a sustainable development programs for villages/ethnic societies

Special mention must be made of Joint Forest Management (JFM) and Community Forest Management (CFM). These two forest management strategies were envisaged in the National Forest Policy of Government of India. Both these seek the active and real involvement of local ethnic community in forest management. In other words, the State Forest Departments and the forest dwelling people share the management activities of the forest. These two (JFM and CFM) management methods (i) promote cooperation (ii) appreciate diversity (iii) involve the collective mind of the community (iv) involve collective responsibility and accountability (v) allow equal opportunity and access to resources and benefits (vi) make everyone’s voice to become important (vii) enable joint planning and management, and (viii) are not target- or product-oriented (Ravindranath et al., 2000). As a result, the process of forest management primarily promotes the active participation of the community. Local tribals are now evincing keen interest to develop degraded forests near them. In India 30 States have been selected for JFM, 1,813 Forest Protection Committees have been formed in the undivided Andhra Pradesh after its launch in 1993. In Tamil Nadu JFM was started in 1977 with the help of Village Forest Councils and with the thrust areas of forests regeneration and development of degraded forest. Both JFM and CFM have become successful with the help of Self-Help Groups, resulting not only in enhancing the total forested area but also in helping the ethnic societies to sustainably use the forest products for the their livelihood.

In 1999, the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) of Government of India prepared a National Policy and Macro-level Action Strategy on Biodiversity through a consultative process. This was called the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP). Towards the goal of preparing NBSAP, MoEF was funded by GEF. The execution of NBSAP process was entrusted to the Technical and Policy Core Group (TPCG) coordinated by the NGO, Kalpavriksh and the Biotech Consortium India Ltd. This was operated between 2000 and 2002. The NBSAP was one of the largest environmental planning exercises carried out ever in India for the following reasons: (i) it was carried out at five different levels (local, State/Union Territory, Ecoregion, Thematic and National); (ii) It involved the entire biodiversity spectrum (both wild and domesticated/cultured) at all the levels of biodiversity (genes, species, ecosystems); (ii) the plan involves a range of aspects like scientific, technological, social, cultural, economic, political, ethical, moral and gender relations. There were 14 broad thematic areas, four cross-cutting ones and 25 sub-themes; (iv) consequent on (i) to (iii) above the plan involved all categories of people, institutions and major stakeholders. Eight interstate ecoregions were suggested for which NBSAP was to be prepared. The E. Ghats was one such ecoregion and this Ecoregion group was coordinated by Prof. T. Pullaiah and helped by Prof. K.V. Krishnamurthy and the Botanical Survey of India, Southern Circle. Based on various inputs the Draft Action Plan for E. Ghats Ecoregion was prepared and sent to the coor-dinating body of NBSAP (Krishnamurthy, 2001; Pullaiah, 2001). This Draft Action plan was finalized after giving details on nine aspects of E. Ghats (see details Krishnamurthy et al., 2014). This important document was very helpful in taking adequate conservation and management measures.

10.5BIOPROSPECTING AND BIOPIRACY

As per the utilitarian approach of ethnobiology, ethnic knowledge (TKS or IKS) on various plant uses is being increasingly exploited, particularly by the western world. The process involved in this is called bioprospecting (see also Chapter 12 in this volume). Bioprospecting is vital for pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, cosmoceutical, biotechnological and agricultural industries (see Krishnamurthy, 2003). TKS on plants is often possessed within a tribal society by all its members or may be held by specialists, elders, shamans, clan heads or by women. The importance of TKS, especially with reference to bioprospecting has been grossly underestimated. But today the vast advancements in scientific documentation and understanding of TKS have vastly improved the situation. The sacred bondage between traditional societies and Nature has also been realized by Western Societies, culminating in the recognition of ‘Cultural Landscapes’ by UNESCO. Such recognition had very great implications for ownership of traditional knowledge and, hence, for intellectual property rights (IPR). Loss of TKS, even if it is bits and pieces, will lead to the losing of control over vital information by the traditional societies which have been theirs for several hundreds of years. The existing mechanisms are inadequate to effective protect the genuine rights of traditional societies. Hence, biopiracy was rampant even until about five years back. As of today, IPRs are the most important legal measures available for protecting knowledge, discoveries, innovations, inventions and novel practices and products. Patents, which are the best known of these IPRs however, are of very limited or even no value to traditional communities as there are several difficulties in documenting their knowledge and in identifying the actual owner/inventor of that knowledge. In many cases, TKS is in the public domain and hence do not have the required ‘uniqueness.’ There are other difficulties as well (see details in Krishnamurthy, 2003).

Indigenous societies have recently become better informed, organized and more articulate. They have started to assert their rights forcefully through their own actions, networks and databases. Many traditional societies have entered into community forest management and participatory forest management agreements. They have got their rights to utilize forest products (on which they were all along dependent) even in protected areas in the buffer zones.

10.6ENDOGENOUS DEVELOPMENT

Conservation of ethnic knowledge on plants requires protection of tribal peoples, who possess this knowledge. The tribal peoples are vulnerable to a range of social, cultural and economic changes that influence them and their knowledge in various ways. Often, they are forced to migrate from their habitats in search of better life, education, job and money. Many young tribals are attracted to Western ways of life and do not have interest to acquire the traditional knowledge from their elders or other members of the society. Moreover, in the last two centuries there is an increasing dominance of the Western culture, values, science and technology and these have increasingly replaced traditional knowledge systems and cultures, particularly in India due to the colonial rule. The traditional ethnic societies and people are either rejected or are marginalized and have also moved away from their rich cultural background.

In the light of the above, endogenous development is very important. It is based mainly, though not exclusively, on the locally available resources, local knowledge, culture, and leadership. It is open to integrating traditional and outside knowledge and practices in order to protect the indigenous community and its people. It helps the tribals through participatory development, local management of natural resources and ecological processes, low external input, sustainable agriculture and biodiversity, etc. Endogenous development neither implies narrowly defined development, nor romanticizes or rejects traditional knowledge. On the contrary, it is to be considered as complementary to the ongoing technological process. It addresses the local needs and contradictions, uses local potentials, enhances local economics and links them to international systems. It supports co-existence and co-evolution of a number of cultures and promotes intercultural research, exchange and dialogs. Thus, endogenous development brings together global and local knowledge’s (Haverkortt et al., 2003).

The Compass program of Netherlands has supported endogenous development in south India through FRLHT, the NGO based at Bangalore. The following components have been identified by Compass for supporting endogenous development: (i) building on locally available resources; (ii) objectives based on locally felt needs and values; (iii) in-situ reconstruction and development of local knowledge systems through understanding, testing and improving local practices and enhancing the dynamics of local knowledge process; (iv) maximizing local control of development; (v) Identifying development niches based on the characteristic of each local situation; (vi) selective of use the external resources; (vii) retention of benefits in the locality itself; (viii) share and exchange experiences between different ethnic societies; (ix) training and capacity building; (x) developing networks and partnerships; and (xi) understanding systems of knowing, learning and experimenting.

The efforts taken by IDEA (Integrated Development through Environmental Awakening) in northern E. Ghats towards endogenous development is worth mentioning since community ownership as well as traditional leaders (Shamans) and their norms, taboos, and customary practices related to natural stability and cultural identity are breaking down. IDEA has been facilitating a process to halt degradation of cultural identity, TKS and natural resources of tribals since 1985 (in 300 villages in Odisha and northern undivided Andhra Pradesh). It has taken various measures, such as documentation, action research, formation of tribal network, traditional seed conservation (with a collection of about 285 traditional seed varieties), vegetable conservation (with about 243 wild vegetables, edible tubers, berries and nuts), traditional medicinal plants (about 500 species), besides undertaking serious endogenous development programs. These programs are related to ethnoveternary practices, biopesticides, transformation of traditions to ecofriendly processes, traditional weed management, strengthen-ing traditional leaders and tribal identity, developing organic markets, eco-tourism, popularizing traditional knowledge, protecting tribal cosmovisions and belief systems, etc. (Gowtham Shankar, 2003).

There is great variability of endogenous development options if one considers seriously the diversity of worldviews, values, practices, knowledge concepts and ecological and political context. Hence, there are a number of opportunities and constraints related to endogenous development of ethnic societies in E. Ghats and the adjacent Deccan region, as in any other traditional societies of the world. In order to meet these opportunities and constraints we must first create the enabling environment (Haverkort et al., 2003) at the local, regional, national and international levels.

KEYWORDS

•Conservation

•Databases

•Documentation

•Endogenous Development

•Traditional Botanical Knowledge

REFERENCES

Balaguru, B., John Britto, S., Nagamurugan, N., Natarajan, D. & Soosairaj, S. (2006). Identifying conservation priority zones for effective management of tropical forests in Eastern Ghats of India. Biodiv. Conserv. 15, 1529–1543.

Biswal, A.K. & Sudhakar Reddy, C. (2007). Prioritization of taxa for conservation in Orissa. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 73–74.

Busy, J.R. (1997). Management of information to support conservation decision making. In: D.L. Hawksworth, P.M. Kirk & S. Dextre Clarke (Eds.). Biodiversity Information: Needs and Options. Wallingford, UK: CAB International.

Chavan, V. & Chandramohan, D. (1995). Databases in Indian Biology: the state of art and prospects. Curr. Sci. 68, 273–279.

Cornish, C. & Nesbitt, M. (2014). Historical Perspective on western Ethnobotanical Collections. In: J. Salick, K. Konchar & Nesbitt, M. (Eds.). Curating Biocultural Collections, Kew: Kew Publishing Royal Botanical gardens. pp. 271–293.

Gadgil, M., Devasia, P. & Seshagiri Rao, P.R. (1995). A comprehensive framework for nurturing practice ecological knowledge. Centre for Ecological Science, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, Karnataka. pp. 1–74.

Ganeshaiah, K.N. & Uma Shaanker, A. (1998). Contours of Conservation – A national agenda for mapping biodiversity. Curr. Sci. 75, 292–298.

Geevan, C.P. (1995). Biodiversity Conservation Information Networks: A Concept Plan. Cur. Sci. 69, 906–914.

Giriraj, A., Shilpa, G., Sudhakar Reddy, C., Sudhakar, S., Beierkuhnlein, C. & Murthy, M.S.R. (2007). Mapping the geographical distribution of Pterocarpus santalinus L.f. (Fabaceae) – an endemic and threatened plant species using ecological niche modeling. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 446–457.

Gowtham Shankar (2003). Building on Tribal resources. Endogenous Development in the Northern Eastern Ghats. pp. 115–128. In: B. Haverkort, K. Van’t Hooft & W. Hiemstra (Eds.). Ancient Roots, New Shoots-Endogenous Development in Practice. London: Compas, Zed Books.

Haverkort, B., Van’t hooft, K. & Hiemstra, W. (Eds.). (2003). Ancient Roots, New Shoots-Endogenous Development in Practice., London: Compas, Zed Books.

Henry Jonathan, K. (2008). Sacred groves – the need for their conservation in the Eastern Ghats region. EPTRI-ENVIS Newsletter 14(3), 3–5.

Henry Jonathan, K. & Solomon Raju, A.J. (2007). Threats to biodiversity of Eastern Ghats: The need for conservation and management measures. EPTRI-ENVIS Newsletter 13(2), 9–10.

Hughes, J.D. & Chandran, M.D.S. (1998). Sacred groves around the earth: an overview. In: P.S. Ramakrishnan (Ed.). Conserving the Sacred for Biodiverisity Management, New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., pp. 69–85.

Kosambi, D.D. (1962). Myth and Reality: Studies in the Formation of Indian Culture. Bombay: Popular Press.

Krishnamurthy, K.V. (2001). Report on National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) for Part of the Tamil Nadu Sector of Eastern Ghats Ecoregion. Tiruchirappalli, India.

Krishnamurthy, K.V. (2003). Text Book on Biodiversity. Science Publishers, New Hampshire, USA.

Krishnamurthy, K.V. (2012). The need for estimation of minimum viable population size for the threatened plants of India. In: G. Maiti & S.K. Mukherjee (Eds.) Multidisciplinary Approaches in Angiosperm Systematics. Vol. II. Publication Cell, Univ. Kalyani, W. Bengal, India. pp. 141–148.

Krishnamurthy, K.V., Murugan, R. & Ravikumar, K. (2014). Bioresources of the Eastern Ghats: Their Conservation and Management. Dehra Dun: Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh.

Malhotra, K.C., Gokhale, Y., Chatterjee, S. & Srivastava, S. (2001). Cultural and Ecological Dimensions of Sacred Groves in India. IWSA, New Delhi and Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya, Bhopal, India.

Meffe, G.K. & Carroll, C.R. (1994). Principles of Conservation Biology. Sunderland, Mass, USA: Sinauer Associates.

Murthy, M.S.R., Sudhakar, S., Jha, C.S., Sudhakar Reddy, C., Pujar, G.S., Roy, A., Gharai, B., Rajasekhar, G., Trivedi, S., Pattanaik, C., Babar, S., Sudha, K., Ambastha, K., Joseph, S., Karnatak, H., Roy, P.S., Brahmam, M., Dhal, N.K., Biswal, A.K., Mohapatra, A., Mohapatra, U.B., Misra, M.K., Mohapatra, P.K., Mishra, R., Raju, V.S., Murthy, E.N., Venkaiah, M., Venkata Raju, R.R., Bhakshu, L.M., Britto, S.J., Kannan, L., Rout, D.K., Behera, G. & Tripathi, S. (2007a). Biodiversity Characterization at landscape level using Satellite Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System in Eastern Ghats. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 394–405.

Murthy, M.S.R., Sudhakar, S., Jha, C.S., Sudhakar Reddy, C., Pujar, G.S., Roy, A., Gharai, B., Rajasekhar, G., Trivedi, S., Pattanaik, C., Babar, S., Sudha, K., Ambastha, K., Joseph, S., Karnatak, H., Roy, P.S., Brahmam, M., Dhal, N.K., Biswal, A.K., Mohapatra, A., Mohapatra, U.B., Misra, M.K., Mohapatra, P.K., Mishra, R., Raju, V.S., Murthy, E.N., Venkaiah, M., Venkata Raju, R.R., Bhakshu, L.M., Britto, S.J., Kannan, L., Rout, D.K., Behera, G. & Tripathi, S. (2007b). Vegetation land cover and Phytodiversity Charaterization at Landscape Level using Satellite Remote Sensing and Geographic information system in Eastern Ghats, India. EPTRI-ENVIS Newsletter 13(1), 2–12.

Natarajan, D., John Britto, S., Balaguru, B., Nagamurugan, N., Soosairaj, S. & Arockiasamy, D.I. (2004). Identification and conservation priority sites using remote sensing and GIS – A case study from Chitteri hills, Eastern Ghats, Tamil Nadu. Curr. Sci. 86, 1316–1323.

Noorunnisa Begum, S., Ravikumar, K., Vijaya Kumar, R. & Ved, D.K. (2004). Profile of medicinal plants diversity in Tamil Nadu MPCAs. In: Abstracts – Natl. Sem. New Frontiers in Plant Taxonomy and Biodiversity Conserv. TBGRI, Tiruvananthapuram, India. pp. 97–98.

Pandravada, S.R., Sivaraj, N., Kamala, V., Sunil, N. & Varaprasad, K.S. (2008). Genetic Resources of wild relatives of crop plants in Andhra Pradesh – Diversity, Distribution and Conservation. Proc. A.P. Akademi of Science, Special Issue on Plant Wealth of Andhra Pradesh 12, 101–119.

Pandravada, S.R., Sivaraj, N., Kamala, V., Sunil, N., Sarath Babu, B. & Varaprasad, K.S. (2007). Agri-Biodiversity of Eastern Ghats-exploration, collection and conservation of crop genetic resources. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 19–27.

Pullaiah, T. (2001). Draft Action Plan – Report on National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan: Eastern Ghats Eco-Region. Anantapur, India.

Rao, R.S. (1998). Vegetation and valuable plant resources of the Eastern Ghats with specific reference to the Andhra Pradesh and their conservation. In: The Eastern Ghats – Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 59–86.

Ravindranath, N.H., Murali, I. & Malhotra, K.C. (2000). Community Forest Management and Joint Forest Management in India. New Delhi, India: Oxford & IBH.

Rawat, G.S. (1997). Conservation status of forests and wildlife in the Eastern Ghats, India. Environ. Conserv. 24, 307–315.

Sastry, A.R.K. (2002). Hotspots concept: Its application to the Eastern Ghats for biodiversity conservation. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 184–186.

Shiva, V. & Ramprasad, V. (1993). Cultivating Diversity. Research Foundation for Science, Technology and National Resources Policy. Dehradun, India.

Shiva, V., Anderson, P., Schiicking, H., Gray, A., Lohman, L. & Cooper, D. (1991). Biodiversity: Social and Ecological Perspectives. New Jersey, USA: Zed Books.

Singh, A.K. & Varaprasad, K.S. (2008). Criteria for identification and assessment of agro-biodiversity heritage sites: Evolving sustainable agriculture. Curr. Sci. 94, 1131–1138.

Sivaraj, N. (1991). Phenology and reproductive ecology of angiosperm taxa of Shervaroy hills (Eastern Ghats, South India). PhD Thesis, Bharatidasan University, Tiruchirapallu, India.

Sivaraj, N. & Krishnamurthy, K.V. (1989). Flowering phenology in the vegetation of Shervaroys (Eastern Ghats: South India). Vegetatio 79, 85–88.

Sivaraj, N. & Krishnamurthy, K.V. (1992). Fruiting behavior of herbaceous and wood flora of Shervaroy hills. Trop. Eco. 33(2), 55–63.

Sivaraj, N. & Krishnamurthy, K.V. (2002). Phenology and reproductive ecology of tree taxa of Shervaroy hills (Eastern Ghats, South India). In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 69–87.

Sivaraj, N., Pandravada, S.R. & Krishnamurthy, K.V. (2007). Gender distribution and breeding systems among medicinal plants of Eastern Ghats. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 148–153.

Solomon Raju, A.J. (2007). Bird-flower interactions in the Eastern Ghats. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 281–285.

Solomon Raju, A.J. & Henry Jonathan, K. (2010). Reproductive ecology of Cycas beddomei Dyer (Cycadaceae), an endemic and critically endangered species of southern Eastern Ghats. Curr. Sci. 99, 1833–1840.

Solomon Raju, A.J. & Purnachandra Rao, S. (2002a). Pollination ecology and fruiting behavior in Acacia sinuata (Lour.) Merr. (Mimosaceae), a valuable non-timber forest plant species. Curr. Sci. 82, 1467–1471.

Solomon Raju, A.J. & Purnachandra Rao, S. (2002b). Reproductive ecology of Acacia concinna (shikakai) and Semecarpus anacardium (marking nut), with a note on pollinator conservation in the Eastern Ghats of Visakhapatnam district, Andhra Pradesh. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 316–326.

Solomon Raju, A.J., Puranchandra Rao, S., Zafar, R. & Roopkalpana, P. (2003). Bird-flower interactions in the Eastern Ghats forests. EPTRI-ENVIS Newsletter 9(3), 2–5.

Solomon Raju, A.J., Purnachandra Rao, S. & Ezradanam, V. (2002). Bird-pollination in Helicteres isora and Spathodea campanulata with a note on their conservation aspects. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 308–315.

Solomon Raju, A.J., Purnachandra Rao, S. & Ezradanam, V. (2004). Pollination by bats and passerine birds in a dry season blooming tree species, Careya arborea, in the Eastern Ghats. Curr. Sci. 86, 509–511.

Solomon Raju, A.J., Venkata Ramana, K. & Henry Jonathan, K. (2009). Anemophily, anemo-chory, seed predation and seedling ecology of Shorea tumbuggaia Roxb. (Dipterocarpaceae), an endemic and globally endangered red-listed semi-evergreen tree species. Curr. Sci. 96, 827–833.

Soosairaj, S., John Britto, S., Balaguru, B., Nagamurugan, N. & Natarajan, D. (2007). Zonation of conservation priority sites for effective management of tropical forests in India: a value-based conservation approach. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 5(2), 37–48.

Sridhar Reddy, M. & Ravi Prasad Rao, B. (2007). Observations on distribution and population structure of Pterocarpus santalinus L.f. in Kadapa hill ranges. In: Abstracts – Internatl. Sem. Changing Scenario in Angiosperm Systematics. Shivaji University, Kolhapur, India. pp. 46–47.

Srinivasa Rao, A. (2007). Networking of Digital Resources on the Environment of Eastern Ghats – the EPTRI-ENVIS Perspective. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 602–607.

Sudhakar Reddy, C., Rout, D.K., Pattanaik, C. & Murthy, M.S.R. (2007a). Mapping of priority areas of conservation significance in Eastern Ghats: A case study of Similipal Biosphere Reserve using Satellite Remote Sensing. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 435–438.

Sudhakar Reddy, C., Varma, Y.N.R., Brahmam, M. & Raju, V.S. (2007b). Prioritization of endemic plants of Eastern Ghats for biological conservation. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 3–13.

Suresh Babu, M.V., Srinivasa Rao, V. & Ravi Prasad Rao, B. (2007). Cycas beddomei Dyer (Cycadaceae). A global endemic of Tirupati and Kadapa hills. In: Abstracts – Internatl. Sem. Changing Scenario in Angiosperm Systematics. Shivaji University, Kolhapur, India. p. 54.

Swain, P.K., Siva Rama Krishna, I. & Murty, B.L.N. (2008). Sacred Groves – Their Distribution in Eastern Ghats Region. EPTRI-ENVIS Newsletter 14(4), 3–5.

Swaminathan, M.S. (1997). Implementing the global biodiversity Convention: IPR for public good. In: P. Pushpangadan, K. Ravi & Santhosh, V. (Eds.). Conservation and Economic Evaluation of Biodiveristy. Vol.2. New Delhi: Oxford & IBH Publishing Co.Pvt. Ltd. pp. 399–412.

Uma Ramachandran. (2002). Bettering Agriculture to Preserve Mountain Ecosystems. Examples from Eastern Ghats. In: Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 548–557.

Venkaiah, M. (1998). Plant biodiversity in Vizianagaram district, Andhra Pradesh. In: The Eastern Ghats – Proc. Natl. Sem. Conserv. Eastern Ghats. ENVIS Centre, EPTRI, Hyderabad, India. pp. 1–5.