ONE

Capital Order

GROWING CHAOS

In 1903 renowned muckraking journalist Lincoln Steffens traveled to Chicago in search of a scoop on the graft, corruption, and brutality that Americans across the nation associated with the country’s second largest metropolis. He did not exactly find the story he was expecting to write. After all, this was a city run by Carter Harrison II, a mayor who had proven his reformist mettle by working with the “goo-goos” in the Municipal Voter’s League (MVL)—a group of upright businessmen, professionals, and social workers unified by the mission of bringing “good government” to their city—to appoint city council committees on a nonpartisan basis. And Harrison had just a year earlier taken an unequivocal stand in defense of the public interest in his dealings with the traction magnates—the robber barons looking to cash in on their soon-to-expire franchises on the tangle of streetcar lines inflicting impossible traffic jams downtown. If, for his part, Steffens judged Harrison a reluctant reformer, the mayor nonetheless advocated municipal ownership of mass transit and a popular referendum to decide the issue—a stance that certainly did not win him favor with railroad tycoon Charles Tyson Yerkes and the so-called Gray Wolves on the city council who had enabled him to amass a fortune of some $30 million since his arrival in Chicago more than a decade earlier. What impressed Steffens most of all were the earnest efforts of the MVL and its new secretary, Walter L. Fisher, which gave him cause to proclaim: “The city of Chicago is ruled by the citizens of Chicago.” And yet Steffens did not leave Chicago without something sensational to report. If Chicago reformers seemed to Steffens to be fighting the good fight, they also seemed no match for the miasma of ills that plagued its residents: its tainted drinking water, its unpaved streets, its “stench of the stockyards,” its “insufficient (and inefficient)” police force, its “mobs” and “riotous strikers,” its “extra-legal system of controlling vice and crime.” Summing it all up in the oft-repeated phrase that would come to identify Steffens’s view of Chicago much more than any of his accolades about its engaged citizenry and reformers, he dubbed the city “[f]irst in violence, deepest in dirt; loud, lawless, unlovely, ill-smelling, irreverent, new; an overgrown gawk of a village, the “tough” among cities, the spectacle of a nation.”1

While some may have thought Steffens was merely displaying the hyperbolic flair that was the signature of turn-of-the-century muckraking journalism, his claims were, in fact, right on the mark. By the early twentieth century, Chicagoans were killing each other at an astounding rate; its muddy streets were piled with trash, animal excrement, and seemingly all the detritus of humanity; its rivers were brown with sewage; and its skies black with coal soot. In fact, the vigorous civic engagement Steffens found so remarkable signified that an increasing number of its notables were beginning to reckon with these horrid conditions and with the idea that their city was quickly turning into the world’s reference point for urban dystopia. Indeed, Steffens had arrived in Chicago at the dawning of a new era of reformist zeal, whose intensity had something to do with a growing sense among civic and political leaders that their city had fallen behind other great cities throughout the world in its manner of dealing with the social costs of laissez-faire capitalism. This new reformist spirit had taken shape within the context of what Daniel T. Rodgers has referred to as “the Atlantic Era,” when “American social politics were tied to social political debates and endeavors in Europe through a web of rivalry and exchange.”2 For pioneering social worker Jane Addams, this meant traveling repeatedly to London’s East End to observe the Toynbee Hall social settlement before launching her own Hull House settlement on Chicago’s Near West Side. And for architect Daniel Burnham, who would set to work on his visionary Plan of Chicago several years later, it meant using the inspiration of Baron Haussmann and his renovation of nineteenth-century Paris “to bring order out of the chaos.”3

It came as no surprise to most that Steffens had bestowed upon Chicago the dubious honor of being “first in violence”—certainly in the nation and perhaps in the world. By 1913, its murder rate was four times higher than New York’s and was about fourteen times that of London. In fact, this situation had begun to arouse concern in 1903, when juvenile court judge Richard Tuthill had organized a group of businessmen, religious leaders, and other reform types into an “anti-crime committee” to put pressure on the police, whom they viewed as inefficient in fighting criminal activities, if not complicit with them.4 Holding up Chicago’s startling number of murders in comparison with London’s, the editors of the Chicago Tribune spoke of “an attitude of mind which prevails in Chicago and which cannot be shaken except by long years of struggle on the part of individual Chicagoans to bring individual souls to a nobler conception of individual life.” In the years to come, as racial theories and social Darwinism would take center stage in campaigns to close the country’s borders, anticrime discourses would increasingly identify this “attitude of mind” with African Americans, Mexicans, Asian Americans, and a range of “races” that poured into the country from southern and eastern Europe between the 1880s and 1910s. But in turn-of-the-century Chicago, perceptions of criminality were still surprisingly democratic, more so, it seemed, than in comparable cities. “Crime in Chicago,” the Tribune‘s editors made sure to point out, “is a matter of individual tolerance of sharp, illegal, wrongful, violent practices, either at mahogany tables or in dark alleys.”5

Chicago in the first decade of the twentieth century was certainly a place where even political officials at times settled their arguments with their fists, and one’s ability to do so convincingly could earn respect. For example, when, as a young foreman for the Chicago Sanitary District in 1907, future mayor Edward Kelly punched out an insubordinate worker, his supervisor, Robert McCormick (a staunch Republican and future owner and publisher of the Chicago Tribune), granted him a raise and a promotion. McCormick told him he admired his “guts,” as the story goes. Nonetheless, in most people’s minds the violent crime problem that was the object of law-and-order campaigns and sensationalized newspaper reportage belonged almost exclusively to Chicago’s laboring classes. “Homicide,” as historian Jeffrey Adler has argued, “was a public and shockingly visible activity in late-nineteenth-century Chicago,” where a good many murders took place in and around saloons, brothels, and other spaces defined by the male working-class “sporting culture” of the time.6 And it was significant that a relatively large proportion of the city’s rank and file worked in the most brutal of workplaces: the packinghouses, which, by the turn of the century, had become Chicago’s largest sector of employment. The link between the bloody entrails on the killing floors and the bloody brawls in the streets was irresistible. “Men who crack the heads of animals all day,” Upton Sinclair famously quipped in The Jungle, “seem to get into the habit, and to practice on their friends, and even on their families.”7 However, Chicago’s national reputation for violence had also come, in part, from the spectacles of violence and destruction wrought by the Haymarket bombing of 1886 and the Pullman Strike of 1894, both of which witnessed striking workers battling the local forces of order and federal troops in its streets. These events were so threatening to Chicago’s upper crust that a group of affluent businessmen living along Prairie Avenue’s “Millionaire’s Row” in the South Loop commissioned architects Daniel Burnham and John Wellborn Root to design the five-story, fortress-like First Regiment Armory at 1552 S. Michigan Avenue for the purpose of stationing troops and armaments just three blocks from their homes.

Hence, the civic-minded folks seeking to root out the sources of criminality in the first decade of the twentieth century, some of whom rubbed elbows with the residents of Prairie Avenue around mahogany tables, went first looking for them down “dark alleys.” In 1900, for example, a group of concerned citizens and settlement workers constituted themselves into the Investigative Committee of the City Homes Association and fanned out into some of the city’s impoverished Jewish, Italian, and Polish tenement districts around the Near West and Near North Sides with pencils and notepads. Among the six members of the committee were tireless social settlement worker Jane Addams and Anita McCormick Blaine, whose older brother Cyrus McCormick, Jr., had ordered Pinkerton thugs to attack strikers at his McCormick Harvesting Machine Company plant three days before the Haymarket bombing. McCormick Blaine, however, was no apologist for capitalism. She had just finished bankrolling John Dewey’s new Laboratory School at the University of Chicago and its bold experiment of interactive pedagogical approaches in order to imbue in young children a sense of democratic citizenship. Addams, another daughter of a prominent Midwest businessman, was cut from the same cloth. Having cofounded Hull House a decade earlier to serve and better understand the needs of the largely Italian, Jewish, and Greek communities of the Near West Side, Addams thought of her work there as part of the same project of promoting social democratic principles at the grassroots. She placed special emphasis on the recreational programs offered to children, designing art, theater, and sports activities as means for instilling a spirit of democratic cooperation and civic consciousness. That these women had joined sociologist Robert Hunter on this committee demonstrated their belief that the living conditions prevailing in Chicago’s tenement districts threatened the goals they held so dear.

Allowing no alley, privy, or manure box to escape their gaze, McCormick Blaine, Addams, and the other committee members recorded a seemingly endless litany of atrocities: raw sewage seeping into basements packed with families and into alleys where small children played; yards covered in manure and rotting garbage; chickens, horses, and cows living in and around apartments—all emitting unbearable odors and noises that forced residents to keep their windows closed, even during the suffocating heat of a Chicago summer. If Jacob Riis had made New York the emblem of tenement ills with his stunning photojournalism in How the Other Half Lives a decade earlier, the Investigative Committee of the City Homes Association, whose observations were gathered into a published report entitled Tenement Conditions in Chicago, insisted that conditions in Chicago were no less serious. Moreover, unlike older cities such as New York and London, which had been addressing tenement problems for years with an array of city ordinances, such legislation in Chicago was either nonexistent or unenforced. “There is probably no other city approximating the size of Chicago, in this country or abroad,” they asserted, “which has as many neglected sanitary conditions associated with its tenement-house problem.” “The conditions here,” they concluded, “show how backward, in some respects, the City of Chicago is.”8

To be sure, viewed from its tenement alleys, Chicago may have appeared backwards. But such perceptions also reflected the lofty standards of some of its leading reformers, who had already made the city a pioneer in some important ways. By the turn of the century Hull House represented the cutting edge of the nation’s settlement house movement; Chicago’s juvenile court—the world’s first—was providing a widely recognized model for a new case-by-case approach that emphasized rehabilitation over punishment; and John Dewey was trying to revolutionize the country’s educational system at the University of Chicago, which, when it had opened its doors in 1892, was the first university in the country to house a sociology department. Even on the tenement housing issue, Chicago was not exactly a laggard. In fact, the city’s health department had been inspecting buildings and approving construction plans since the early 1880s. But the rapid spread of tenement districts overwhelmed its monitoring capacities. Chicago seemed backwards to reformers in large part because its authorities had failed to keep up with its breathtaking growth in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when the population had more than quadrupled, from just over 400,000 to some 1.7 million.

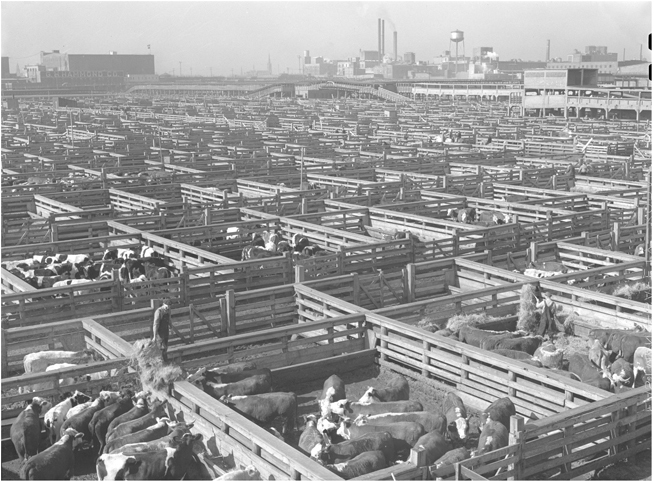

While the many skyscrapers shooting upward from the bustling streets of the Loop business district during these decades attested to the new legions of white-collar workers making the city their home, industrialization was a key driver of this spectacular growth. Indeed, if Chicago’s breathtaking population growth made it an outlier in comparison with other large cities, the expansion of its industrial capacity was even more extraordinary. Between 1880 and 1900, the number of manufacturing workers in the city nearly quadrupled and the number of manufacturing establishments more than doubled.9 Leading the way was the meatpacking sector, which by the turn of the century had captured an 80-percent share of the domestic market in packaged meat, making Chicago, in the words of local poet and journalist Carl Sandburg, “Hog Butcher for the World.” At that time, Chicago’s biggest meatpacking plants—Armour, Swift, and Morris—were among the thirty largest factories in the United States. Meatpacking workers constituted 10 percent of the city’s wage labor force, and some 30 percent of Chicago’s manufactures came out of the mammoth Union Stockyards at the southwestern edge of the city in the form of “Chicago dressed meat”—a brand that was shuttering butcher shops throughout the heartland. By 1900 the stockyards, perhaps the largest single industrial plant in the world, had expanded to 475 acres, with a pen capacity of more than 430,000 animals, 50 miles of road, and 130 miles of railroad track along its perimeter. During that year, 14,622,315 cattle, sheep, hogs, and horses passed through its pens, nine times the number of livestock herded through its gates in its first year of operation in 1866; by the 1920s, this number would surpass 18 million.10

FIGURE 1. The Union Stockyards. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Chicago’s dramatic industrial growth, however, was also propelled by its massive steel works along the lakefront in the southeastern corner of the city. In 1889, most of Chicago’s major steel mills merged to form Illinois Steel, making it, at the time, the world’s largest steel manufacturer. In 1902, another merger engineered by New York banker J.P. Morgan saw Illinois Steel (then called Federal Steel) absorbed into the industrial giant U.S. Steel, the world’s largest business enterprise. At that time the South Works site of steel production employed 3,500 men and covered some 260 acres; twelve years later, 11,000 people worked there. A number of other mills, such as Iroquois Steel, Wisconsin Steel, the Federal Furnace Company, and Interstate Iron and Steel Company, opened to the south of U.S. Steel around this time, and in 1906 U.S. Steel began operations in its massive Gary Works, which by the 1920s employed some 16,000. In the years to come, the steel corridor extending from the southern part of Chicago to Gary, Indiana, would make the region one of the world’s top steel producers.

Moreover, a sizable amount of the millions of tons of steel being turned out in Chicago did not have to go very far. By the turn of the century the raw-materials needs of a number of Chicago’s heavy industries were rising sharply, creating corresponding labor demands. In 1902, International Harvester—the by-product of the merger of McCormick Harvesting Machine Company with four other Chicago farm equipment makers—launched Wisconsin Steel to assure its steel supply as it gathered an 80-percent share of the world market in grain harvesting equipment. Within eight years the company was grossing about $100 million in annual sales and employing more than 17,000 workers in the Chicago area. Around this time, the Pullman Company became another big purchaser of Chicago-made steel as its production shifted from wooden to steel sleeper cars in its company town of Pullman fourteen miles south of the Loop, where its workforce increased from 6,000 to 10,000 between 1900 and 1910. In addition, a significant and growing portion of the steel produced within the Chicago-Gary corridor was hauled up to the Loop to be used in the construction of the steel skeletons holding up the city’s many imposing skyscrapers.

Beginning in the 1880s, Chicago, along with New York, had quickly emerged as a pioneer in the construction of skyscrapers, with Chicago School architects such as Burnham, Root, and Louis Sullivan designing many of the city’s landmark buildings. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, according to architectural historian Carol Willis, “the dominant aesthetic for office buildings in Chicago was to appear as big as possible by rising as a sheer wall above the sidewalks.”11 Often spanning a quarter of a city block and rising sixteen to twenty stories, these palazzo-style buildings typically contained ornate commercial courts with shops, services, and restaurants covered by glass canopies—signature features that sought to define the professionalism and class status of the white-collar workforce in the “City of Big Shoulders.”12 In fact, “big shoulders” by the tens of thousands were employed to construct these massive buildings, whose proliferation had, by the 1920s, moved Chicago into second place in the nation in number of headquarter offices.

Similar designs, moreover, characterized the swanky department stores that so elegantly displayed the wares of retailers such as Marshall Field and Carson Pirie Scott. The brisk expansion of Chicago’s commercial, financial, insurance, real estate, and advertising sectors during this era created an enormous need for retail and office space. And leading the way were burgeoning mail-order retailers such as Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck and Co., which, by bringing the fashions and necessities of modern life to folks in the hinterlands, had grown into some of the nation’s largest business enterprises by the 1910s. Many of the fashions being mailed out, moreover, were produced right there in Chicago, which by the turn of the century had become the country’s second largest production center for men’s clothing. Making it possible to get all these workers and shoppers to the Loop was the rapid expansion of the city’s elevated railroad system, which grew from 35 miles of line in 1900 to 70 miles by 1914, establishing Chicago’s “L” as one of the longest metropolitan railways in the world.

All this to say that Chicago’s economy and workforce expanded at breakneck speed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in comparison with most of the world’s major cities. The city’s phenomenal growth was due in part to its central location within the country’s railroad network, which made it the “gateway” between east and west, in part to its extraordinarily diversified economy, and in part to the Great Fire of 1871, which by razing more than 18,000 structures across some 2,000 acres downtown, created the conditions for a building boom that worked to modernize the young city at a breathtaking pace. Yet the commercial forces unleashed in this perfect storm of redevelopment after the Great Fire had devastating effects on the city’s infrastructure. They created a jumbled mess of railroad tracks, rail yards, and service buildings out of the lakefront; huddled poorly constructed wood-frame tenements around muddy, unpaved streets at the Loop’s periphery; cut up the city with railroad tracks; and cluttered the Chicago River’s banks with factories, smokestacks, and ramshackle warehouses. And this had all come to pass in a city that had shown it had the wherewithal to move mountains. Chicago, after all, had managed to put on the greatest spectacle in modern history when the city’s brass had marshaled the resources and know-how to hastily conjure the majestic White City—the neoclassical fantasyland setting for the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893—out of some 600 acres of swamp and mud in Jackson Park. Over 27 million visitors had walked through the Beaux Arts pavilions of this city-within-a-city, marveling at wonders of modernity collected from the four corners of the world. Then, in 1900, the city had displayed its engineering prowess by permanently reversing the Chicago River’s flow with the completion of the Sanitary and Ship Canal, thus stopping the outbreaks of cholera and typhoid caused by sewage pouring into the city’s Lake Michigan drinking water. Yet, regardless of such technological feats, Chicago in the early 1900s nonetheless seemed like a city struggling in vain to make order out of the chaos that had taken it captive.

In addition to the built environment, this sense of chaos permeated the social fabric. Profound social instabilities grew out of the massive wave of immigrants and migrants that washed over Chicago between 1890 and 1910, when the city’s foreign-born population increased from under half a million to almost 800,000. By 1910, the foreign born and their children made up almost 80 percent of the population. Moreover, the industrial juggernaut was pulling its immigrant laborers from other reaches of Europe than it had in the past. At the turn of the century, the Germans, the Irish, and the Poles had been the largest ethnic groups. By the 1910s, the Poles were on their way to becoming the most prominent white ethnic group; the Germans and the Irish were proportionally on the decline; and a range of new ethnic groups from points in southern and eastern Europe were exerting their presence in the streets and neighborhoods. While Chicago’s population roughly doubled between 1890 and 1910, for example, its Italian-born population jumped eightfold and its Jewish population rocketed almost sixteenfold. Greeks and Czechs also poured into the city, which became the central destination in the United States for these groups.13 Moreover, these decades also witnessed the arrival of an increasing number of African American migrants from the South. Between 1890 and 1910, Chicago’s black population more than tripled, jumping from 14,271 to 44,103, which at the time represented 2 percent of the overall population.

The tendency for these new ethnic groups to form close-knit communities accentuated the great changes under way, as native-born Chicagoans saw whole neighborhoods being transformed before their eyes. In the late 1890s, for example, Swedes had dominated the Near North Side “Swede Town” neighborhood around Seward Park; just ten years later it would be commonly referred to as “Little Sicily.” But nowhere was this phenomenon more readily apparent than on the Near West Side, in the immediate vicinity of Hull House, where a number of the city’s most distinctive ethnic neighborhoods sprung up seemingly overnight. A short stroll to the north took one into the “Greek Delta” (later known as Greektown) at the triangle of Halsted, Harrison, and Blue Island Avenue; just to the south lay the “Jew Town” neighborhood around Maxwell Street, with its bustling outdoor market and ramshackle storefront synagogues; and a quick jaunt to the west along Taylor Street took one straight into the heart of Little Italy. To the northwest of Greektown, at the triangle formed by Division, Ashland, and Milwaukee Avenue lay the heart of Polish Downtown. South of Maxwell Street, in the Pilsen area, was the city’s largest Czech community. To the east of Pilsen, Chicago’s largest African American neighborhood, referred to as the “Black Belt,” stretched from the Loop down to the Levee vice district between 18th and 22nd Streets and beyond to 39th Street, encompassing much of the 2nd and 3rd Wards. While such areas of the city came to be associated with a certain predominant group whose imprint appeared in the form of ethnically identifiable saloons, groceries, restaurants, retail shops, places of worship, and meeting spots, these neighborhoods were far from homogeneous. Jews, Italians, Greeks, and blacks collided on a daily basis on the Near West Side; Polish Downtown overlapped with well-defined enclaves of Jews, Italians, and Ukrainians; Czechs and Poles coexisted in Pilsen; and the Back of the Yards neighborhood adjacent to the stockyards mixed Germans, Irish, Poles, Slovaks, Lithuanians, and Czechs. Even African Americans were relatively well distributed throughout the city, settling among Italians and other white ethnics on the Near West and Near North Sides, as well as around the steel mills in the South Chicago community area. In fact, although the forces of segregation were gaining momentum by the early 1900s, as late as 1910 blacks remained less segregated from native-born whites than Italian immigrants.14

Nonetheless, by the early 1900s the social fabric seemed to be coming apart at the seams. Youth gangs and athletic clubs patrolled neighborhood boundaries, engaging in turf battles that reflected both simmering tensions between rival ethnoracial communities and the increasing precariousness of masculinity in a labor market characterized by Taylorist deskilling strategies on the part of employers and downward wage pressures caused by all of the new immigrants ready and willing to fill unskilled jobs. Such circumstances contributed to the wave of lethal violence that made Chicago the nation’s leader in homicides by 1910, as well as to the rise of a new era in racially motivated aggression within the laboring class.15 Particularly emblematic of the new times were the rancorous and vicious labor conflicts that shook the city in the summers of 1904 and 1905.

The first of these, the stockyards strike of 1904, began in the first week of July after the major meatpackers refused to guarantee the wage levels of unskilled packinghouse workers, whom unionists from the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen (AMCBW) believed were being used to undercut the pay and position of skilled butchers. The ensuing strike involved the immediate walkout of some 20,000 workers and lasted two months, with numerous violent clashes pitting strikers and their sympathizers against strikebreakers and the police. While the vast majority of the strikebreakers recruited by the packers were white, black strikebreakers occupied center stage in the drama from the outset. Antiblack violence associated with the strike quickly metastasized as white workers began referring to blacks in general as a “scab race.” Suggestive of the rancorous racial hatred circulating around the affair was a polemic in one labor newspaper that referred to the strikebreakers as “a horde of debased, bestialized blacks . . . brought in[to] the labor market and shipped into the yards as hogs are shipped for the killing floors.”16 Over the summer, African Americans, whether involved in the strike or not, became frequent targets of violence around the stockyards, being pulled off streetcars by mobs or pelted with rocks in the streets. Such injuries were compounded by the strike’s failure, which the butchers of course blamed on the black strikebreakers, who, for their part, lost their jobs as soon as the conflict ended.

The teamsters strike of the following year further escalated the racial situation. Beginning in April as a sympathy strike by the Brotherhood of Teamsters in support of the United Garment Workers (UGW), several of whose members had been fired by Montgomery Ward for a strike months before, the campaign quickly garnered the participation of several thousand workers and turned destructive. Days after the teamsters stopped deliveries to Montgomery Ward, the Chicago Tribune alarmingly reported the outbreak of “riotous demonstrations, blockading of streets, and clashes with the police force.”17 Once again, employers resorted to bringing in black strikebreakers, and once again racial hatred eclipsed class struggle, as attacks on African Americans spilled out of the context of the labor dispute and into the streets and neighborhoods. According to historian David H. Bates, the savage violence that followed was partly due to the race-baiting tactics of the Chicago Employers Association, an antiunion cabal led by Marshall Field’s vice president John G. Shedd and Montgomery Ward executive Robert J. Thorne, which paraded black strikebreakers provocatively through the streets in broad daylight and circulated inflammatory pamphlets asserting that such events portended that blacks would soon “assume a responsible place in society . . . upon equal terms with the whites.”18 The reportage of the main Chicago dailies fanned the flames of race hatred, publishing stories that highlighted the immorality and licentiousness of the black strikebreakers. One Tribune article, for example, characterized them as “Southern ‘darkies,’ who had loafed all their lives along the cotton bales of the Mississippi docks.”19 Although blacks constituted but a small minority of the strikebreakers, white workers were yet again only too eager to take the bait. Strikers threw bricks from rooftops and took to the streets wielding axes, shovels, clubs, and revolvers on an almost daily basis between late April and mid July, a situation that led the strikebreakers to fight back with revolvers and razors. The violence spiraled out of control on April 29th, when thousands of strikers confronted the police in a battle that resulted in three shootings and two stabbings, and then again on May 4th, when mobs broke off from a crowd of more than five thousand and carried out indiscriminate attacks on any blacks in sight. By July, as the strike broke down amidst allegations of bribes exchanged between union leaders and employers, twenty-one people had been killed and over four hundred seriously injured. As in the stockyards strike of the previous summer, workers suffered a crushing defeat. Stained by bribery accusations and the unbridled violence that had shaken the city, the local labor movement limped out of the summer of 1905 towards an uncertain future in which employers would continue to exploit racial fears to break unions.

And yet these tactics worked so effectively because such fears were, in the early 1900s, spreading like an epidemic through the city’s working-class districts. A good many of those venting their rage at blacks during the labor campaigns of 1904 and 1905 were immigrants whose place in the city began to seem increasingly tenuous around this time. This situation was certainly not specific to Chicago. Immigrants from southern and eastern Europe encountered ethnoracial discrimination across the urban United States as they sought to claim their rightful place in their neighborhoods and workplaces during the early years of the twentieth century. Employers regularly refused to hire members of certain groups for higher-paying skilled jobs, both out of an effort to break the unity of the workforce and out of their own racialized sense of which groups were more suited to performing skilled tasks. In Chicago’s packinghouses, the Irish and the Germans were the so-called butcher aristocracy, with Poles and other eastern European groups filling a range of semiskilled and unskilled jobs below them, and blacks performing the dirtiest, lowest-paid work available. Similar arrangements increasingly characterized the workforces of the city’s steel mills and manufacturing plants. Such hierarchies were reproduced within the city’s residential geography, as native-born landlords and realtors commonly refused housing opportunities to blacks and immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. An ethnoracial pecking order was also taking shape out on the streets, where certain groups found themselves to be more susceptible to attacks by street gangs and athletic clubs defending their turf. Here again, the Irish constituted, in the words of sociologist Frederic Thrasher, “the aristocracy of gangland,” and their propensity to target Jews, blacks, and, to a somewhat lesser extent, Poles and Italians conveyed to these groups that their status within the city was far from secure.20 As historians James Barrett and David Roediger have argued, all this constituted a process of “Americanization from the bottom up” in which the Irish served as the key “Americanizers.”21 The power of the Irish to perform this role came from their presence and influence in a range of institutions immigrants dealt with in their daily lives: the school system, the Catholic Church, labor unions, the police department, and the political world.

By the second half of the 1910s, this process of Americanization at the grassroots was increasingly informing immigrants that their proximity to blacks on the job and in their neighborhood placed them in jeopardy. Such feelings would only intensify in the years to come, as a massive wave of African American migrants arrived in the city, and blacks emerged as a new force to be reckoned with at work, in the neighborhoods, and in municipal politics. Between 1910 and 1920, Chicago’s black population would more than double, and in the “red summer” of 1919, the city would witness the most violent and destructive race riot in the nation’s history. But, as the savagery and bloodshed of the stockyards and teamsters strikes revealed, such events should not be viewed as the mere consequences of demographic forces—the reflexes of a tipping point reached. African Americans, after all, constituted a rather inconsequential segment of the city’s turn-of-the-century workforce and a relatively small minority of the strikebreakers brought into the city in 1904 and 1905. And yet their presence aroused an unprecedented level of racial animosity—an animosity fed by the racial uncertainties faced by new immigrants during these years. But if the racial order of the city was evolving by the turn of the century, the events of 1904 and 1905 clearly worked to transform the role race would play in Chicago’s political culture in the years to come, and the fact that some of the city’s leading businessmen had pulled the strings should not be overlooked.

ORDER OUT OF CHAOS

If the stockyards and teamsters strikes of 1904 and 1905 seemed to signify the outbreak of race war for many white workers, such events had very different implications for the city’s business community. For the city’s longstanding power elites—Field, Armour, and Pullman, among others—these explosions of labor violence represented another peak moment in a longer pattern of class warfare that had witnessed epic confrontations between disgruntled workers and the forces of order in the middle years of every decade since the 1870s, when, during the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, Mayor Monroe Heath rounded up some five thousand vigilantes to take on striking railroad workers. While this more recent wave of strikes did not involve the intervention of federal troops, as had been the case in the Great Railroad Strike, the Haymarket affair of 1886, and the Pullman Strike of 1894, the seriousness of the situation was lost on few within Chicago’s rather tight circle of business elites. A range of business interests—meatpackers, retailers, and the press—conspired to ignite the flames of race hatred in 1904 and 1905. The response to the teamsters strike, in particular, revealed the existence of a tight alliance of businessmen—brought together under the auspices of the Employers Association of Chicago—sworn to the task of defeating the unions and making Chicago an “open shop” town. Although the Employers Association had been led by retailing executives John G. Shedd and Robert J. Thorne during the teamsters strike, it had formed three years earlier with financing from a number of prominent bankers to take on strikers seeking to unionize manufacturing workers at Western Electric.22 In managing the battle over public opinion, the Employers Association also clearly had the moral support of some key dailies. But the collusion of the press involved more than this. It is doubtful that the race-baiting tactics of the Employers Association would have met with the same success without the toxic press coverage provided by the supposedly progressive Chicago Tribune and the more avowedly reactionary Chicago Daily News, which painted unionists as hell-bent on destruction and black strikebreakers as moral degenerates.

Indeed, African Americans were not the only ones to suffer from the fallout of these events, and while broader currents were carrying along discourses linking the nation’s decline to the racial others crowding out the “native Anglo-Saxon race,” diatribes against immigrants seemed particularly virulent and somewhat more visible after the strikes. The city’s homicide epidemic merged seamlessly with the vicious labor violence of previous years, shaping perceptions that immigrants were prone to such behavior. By 1907, this premise was guiding the work of the United States Immigration Commission (also known as the Dillingham Commission), which, after analyzing Chicago arrest records between 1905 and 1908, concluded in its 1911 report that southern and eastern Europeans committed more murders than “the peoples of northern and western Europe and the peoples of North America, with the exception of the American negroes.”23 In Chicago, however, this had been a foregone conclusion for years. Discussing the city’s crime problem in the pages of the Chicago Record-Herald in July 1906, for example, police chief John Collins went so far as to refer to the city as a “dumping ground for the different nations of Europe” and a “rallying point for the scum of the earth.”24

And yet, as the work of Jane Addams and Anita McCormick Blaine on Chicago’s tenements revealed, some of the more enlightened middle-class Chicagoans did not put much stock into such ideas. In fact, the city’s business elite was, politically speaking, a somewhat varied crowd, and even within individual families one could find opposing positions on the pressing issues of the day. As historian Maureen Flanagan has argued, middle-class men and women, in particular, tended to have markedly divergent perspectives on the city and its problems during this era.25 But significant differences of opinion existed among men as well. A good many prominent Chicago men would answer the call of Jane Addams during the 1912 presidential election to break with old school Republicans and support the Progressive Party candidate, Theodore Roosevelt. Chicago Tribune vice president Joseph Medill McCormick, for example, signed on as vice chairman for the Progressive Party’s national campaign committee. McCormick’s progressive leanings, however, did not necessarily involve a warm embrace—at least when Chicago was involved—of the kind of lofty pro-labor principles espoused by the Progressive Party platform. Although the Tribune’s coverage of labor affairs had come a long way from the Haymarket era, when, under Joseph Medill’s direction, the paper once referred to strikers as “the scum and filth of the city,” the Tribune’s sensationalist, race-baiting reportage of the stockyards and teamsters strikes under Medill McCormick hardly displayed an unmitigated commitment to the working man.

Medill McCormick, it should not be forgotten, circulated within a milieu in which rabid antiunionism lingered in the air with the thick smoke of fine cigars. He was a loyal member of Chicago’s most elite fraternity of business leaders, the Commercial Club of Chicago, which met each month in the glitzy dining hall of the Auditorium Hotel over an extravagant four-course dinner, concocted with the finest ingredients from overseas, to discuss the business of the city and to hear talks by illustrious guest speakers. The Commercial Club received presidents, senators, congressmen, and cabinet members, as well as the city’s most influential reformers and civic leaders, and meetings were not to be missed. This exclusive club gathered among its members a good many of those leading the charge against the labor movement in the early 1900s: retailing executives like Shedd, Thorne, and John W. Scott of Carson Pirie Scott; wholesalers like John V. Farwell Jr. of Farwell & Company and Frank H. Armstrong of Reid, Murdoch & Company; captains of meatpacking like J. Ogden Armour and his right-hand man, Arthur Meeker; and leading newspapermen like Medill McCormick and Victor Lawson of the Chicago Daily News. To be admitted into the this elite fold, one of its founding members wrote, “a man must have shown conspicuous success in his private business, with a broad and comprehending sympathy with important affairs of city and state, and a generous subordinating of self in the interests of the community.”26 Such sympathy and generosity extended to the helpless and infirm—Farwell, for example, was a big benefactor of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) and its orphan asylum—but stopped well short of able-bodied workers fighting for better living and working conditions. In fact, a great many of the philanthropic activities pursued by the Commercial Club’s members figured somehow into the labor question. The YMCA’s project of evangelizing working-class young men and offering them healthy recreational alternatives to keep them out of the saloons made it one of the Commercial Club’s charities of choice. The great antilabor warriors of the late nineteenth century (all Commercial Club members)—Philip Armour, Cyrus McCormick, and George Pullman—were all generous benefactors of this organization.

Commercial Club members were also quite active as patrons and sponsors of the city’s cultural institutions, with twelve serving on the board of the Art Institute of Chicago and eight on the board of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra by 1907. Yet the involvement of the captains of industry and finance in such endeavors was about more than obtaining marks of prestige and refinement. Between the 1890s and 1910s, both of these institutions, in line with the spirit of Hull House, were engaged in missions to uplift the laboring classes by bringing them into contact with the fine arts. Beginning in 1909, the Art Institute sponsored exhibitions of its works in public park field houses and other neighborhood settings, and in 1914 it worked with the Chicago Board of Education to bring exhibitions into some of the city’s public schools. For its part, the Chicago Symphony Orchestra partnered with the Civic Music Association, an organization launched by the progressive-minded Chicago Women’s Club, to fill the city’s parks and neighborhoods with the refined sounds of classical music. Although banker, Art Institute president, and Commercial Club member Charles Hutchinson spearheaded these activities, they also reflected the fact that the spirit of progressivism embraced by Jane Addams had taken hold among a significant number of the city’s power elites—more so, according to historian Paul DiMaggio, than in other major U.S. cities.27 Within the context of the Commercial Club, this spirit translated into a marked open-mindedness in terms of the speakers chosen to enlighten its members. Jane Addams and pioneering black writer Alain Locke, for example, were among those invited to address the club during these years. Although Hutchinson may not have seen eye to eye with the hardcore antiunionists in the Commercial Club on some issues, he was largely after the same thing: a resolution of the class war that appeared to be threatening Chicago’s place on the national and world stages. The Commercial Club discussed the labor question at a number of its banquets in the early 1900s. The very building in which it often met, the Auditorium Hotel, with its grandiose Auditorium Theater, was a monument to the mission of disarming the laboring classes. Conceived amidst the labor upheavals of the 1880s on a scale that would facilitate the sale of low-priced seats, the entrepreneur behind the Auditorium Theater’s construction, Ferdinand Peck, once claimed that “magnificent music, at prices within the reach of all, would have a tendency to diminish crime and Socialism in our city by educating the masses to higher things.”28 Not surprisingly, Marshall Field and George Pullman were among the project’s biggest investors.

However, amidst the troubling violence of the stockyards and teamsters strikes, it is likely that many of Chicago’s civic and business leaders felt that more dramatic measures were necessary to bring order to the chaos—social and infrastructural—that seemed to be dragging the city down. Such feelings gained increasing expression, in particular, among the members of the Commercial Club and the Chicago Merchants Club, another exclusive organization of leading businessmen that distinguished itself from its homologue by restricting its membership to men under the age of forty-five. In 1907, the two organizations merged, taking the name of the older, more prestigious Commercial Club, in order to more effectively support the grand plan that was to save the city from the chaos enveloping it. The Commercial Club quickly raised the funds required to draft the plan, and the expertise behind it was provided by one of its own members: Chicago’s star architect Daniel Burnham. The result of this private initiative, the Plan of Chicago, was released on July 4, 1909, amidst an aggressive public relations campaign that sought to make the ideas behind the plan building blocks of common sense. By January 1910 the Chicago Plan Commission, the body responsible for drafting and promoting the plan, had raised money for an abridged edition to be assigned to eighth graders as a part of their civics curriculum, the idea being that these adolescents would then educate their parents about the plan’s merits. The Plan of Chicago would need to be sold to the public, the commission realized, if it stood any chance of being implemented.29

Using the city of Paris as its main source of inspiration, the plan called for a number of projects that would “bring order out of the chaos incident to rapid growth” and turn the city into “an efficient instrument for providing all its people with the best possible conditions of living”: a green, uncluttered lakefront area that would facilitate views of the lake to inspire “calm thoughts and feelings”; a scheme for a metropolitan highway system; the consolidation of the intercity railroad passenger terminals into new centralized complexes around the Loop; the incorporation of forest areas around the city into a vast park system; the widening of existing thoroughfares into Parisian-style boulevards and the addition of new diagonal streets to improve the circulation of traffic around the city; and the construction of a massive neoclassical civic center downtown that would serve as a source of pride and unity for all.30 Of course an unabashed commercial logic tied together all of these schemes. The goal of the whole project was to ensure the future “prosperity” of the city, a notion linked, in the final analysis, to the accumulation of wealth more than anything else, as the plan explained:

In creating the ideal arrangement, everyone who lives here is better accommodated in his business and his social activities. In bringing about better freight and passenger facilities, every merchant and manufacturer is helped. In establishing a complete park and parkway system, the life of the wage-earner and of his family is made healthier and pleasanter; while the greater attractiveness thus produced keeps at home the people of means and taste, and acts as a magnet to draw those who seek to live amid pleasing surroundings. The very beauty that attracts him who has money makes pleasant the life of those among whom he lives, while anchoring him and his wealth to the city. The prosperity aimed at is for all Chicago.31

Clearly the objective of attracting, retaining, and generating capital lay at the center of the plan’s moral universe. Tellingly, average citizens here were conceptualized only as wage-earners, and there was little doubt that their health and well-being mattered only in so much as they made them better workers. In this the plan reflected the ethos of the City Beautiful movement of the 1890s and 1900s, of which Burnham was a central figure. Beautification, proponents of this movement believed, would lead to a higher quality of life for the populace, which in turn would bring about social harmony, thereby ensuring optimal conditions for labor productivity. While the labor conflicts of previous years were referred to only obliquely as “frequent outbreaks against law and order,” the plan, in the environmentalist spirit of reformers like Jane Addams, attributed such problems to the “narrow and pleasureless lives” led by the city’s laborers.32 The solution then was to create a city that would function on a grand scale in the same way as the fine arts and recreational initiatives behind which many in the Commercial Club were then throwing their support.

Reflecting on the plan today, it is tempting to interpret its vision of the city as “an efficient instrument” for the accumulation of wealth, its displacement of any sense of social justice by values of business efficiency, and its authorship by a group of businessmen representing an organization called the “Commercial Club” as symptoms of the kind of neoliberal mind-set that would increasingly shape Chicago’s political culture during the postwar decades. And yet if the plan represented a seminal moment in a longer process of neoliberalization that would advance incrementally throughout the twentieth century, it also revealed how much resistance that process ran up against during this era. Moreover, as much as Burnham and his peers viewed business as occupying the driver’s seat, they also invested in the idea of a protective and interventionist state using its power to improve the general welfare of city residents (rather than a truly neoliberal one whose only vocation was to unleash free market dynamics). “It is no attack on private property,” the plan asserted, “to argue that society has the inherent right to protect itself against abuses.”33 Furthermore, strikingly expansive notions of “the people” and “the public interest” were seemingly everywhere to be found—a far cry from the privatized, individualized neoliberal mind-set of the late twentieth century. In perhaps its most definitive passage, for example, the plan characterized the very “spirit of Chicago” as “the constant, steady determination to bring about the very best conditions of city life for all the people, with full knowledge that what we as a people decide to do in the public interest we can and surely will bring to pass.”34 Such democratic ideals extended to some of the city’s most valuable resources, such as the lakefront, which the plan affirmed in no uncertain terms “belong[ed] to the people.” “Not a foot of its shores,” it unambiguously specified, “should be appropriated by individuals to the exclusion of the people.”35 Finally, the great amount of energy and resources the Commercial Club brought to promoting the plan also suggested how far away the city was from where it would be by the late 1950s, when the major planning decisions shaping its future were moving further and further out of the public eye. The city’s business interests would perhaps never again speak in such a unified voice about its planning priorities, and nevertheless the plan’s implementation was far from a fait accompli.

Of course the plan faced other challenges beyond public acceptance. For one thing, raising the funds required by these massive infrastructural projects was going to be difficult because of state-level constitutional limitations on the city’s home rule powers. In other words, Chicago would require authorization from the Illinois state legislature to borrow money or to initiate new tax policies. For another, although the Municipal Voters League had begun to take on the corrupt practices of the Gray Wolves on the city council, it was unable to remove them from office. Preventing the plan’s infrastructural projects from becoming boondoggles was thus not going to be easy. Daniel Burnham and the rest of the Chicago Plan Commission had so little faith in the public authorities that they were ready to raise the necessary funds themselves in order to force the city to carry out the plan’s projects. In fact, considering that the Plan of Chicago devoted an entire chapter to implementation, it is quite reasonable to conclude that practical considerations as well were behind its heartfelt embrace of the people. The people offered valuable leverage in the struggle to force the hand of the public authorities. And the Chicago Plan Commission continued to insist on the active participation of the people into the 1920s, when under the chairmanship of businessman and leading Commercial Club member Charles Wacker, it issued a pamphlet entitled An S-O-S to the Public Spirited Citizens of Chicago.

While the people never really took the cause to heart in the way Burnham and his cohorts had dreamed, the Chicago Plan Commission did manage to work closely and somewhat effectively with every mayoral administration between 1909 and 1931. Chicagoans approved numerous bond issues (some eighty-six between 1912 and 1931) that provided the city with more than $230 million during this era. Key thoroughfares like Michigan Avenue, Roosevelt Road, Western Avenue, and Ashland Avenue were widened; the double-level Wacker Drive was constructed so as to route traffic around the Loop; the new Union Station railroad terminal was built; a huge stretch of the lakeshore was filled and landscaped along with neighboring Grant Park; a recreational parkway was developed along the lakefront; numerous parks and playgrounds were added; and the Forest Preserve District of Cook County acquired several tens of thousands of acres of forest land around the outskirts of the city. Although most of these projects fell short of the plan’s vision, and the majestic civic center in the heart of the city never materialized, Burnham’s scheme had clearly served as a blueprint for these infrastructural changes. By the beginning of the 1930s, however, the role of the Chicago Plan Commission had diminished—in part because much of it had been taken over by the Zoning Commission after the enactment of the city’s first zoning ordinance in 1923—and in 1939 the Chicago Plan Commission was incorporated into the city government as a somewhat powerless advisory body.

These changes corresponded with broader trends shaping municipal administrations across the urban United States, as city governments became active in the business of planning and zoning in the 1920s. According to geographer Robert Lewis, Chicago’s 1923 zoning ordinance was pivotal in transforming the role that city government would play in the local economy. Zoning in Chicago emerged at the outset as more of “an expansionary tool” than an instrument of social reform, with the zoning commission increasingly focusing on economic matters—the promotion of industrial growth and the preservation of real estate values—over social ones.36 Driving the decisions and policies of zoning officials from the outset were fears about competition from other cities. Such orientations reflected the Chicago plan’s priorities of keeping the city’s wealth and wealthy citizens from departing for greener pastures, and of boosting real estate values. Burnham, after all, was an architect, and the Commercial Club was, of course, propertied to the hilt. And yet, somewhat ironically, this private initiative to align the city’s planning priorities with the interests of capital—backed by men who had waged a bloody war against the labor movement—looked to the people in a way that would soon seem foolishly nostalgic. Somewhat paradoxically, as the planning apparatus passed from private to public hands—to zoning and planning officials who were either democratically elected or appointed by officials who were—all the concern with the people and the public interest that Burnham and his cohorts had displayed began to fade. And as the very notion of the people itself slipped into obsolescence, so did concerns with improving the quality of their lives. Burnham’s global vision of a “well-ordered, convenient, and unified city” could never survive within the piecemeal, fractured, political process that planning had become, and the unity and civic spirit he so cherished could never be achieved in the fragmented metropolis that Chicago was quickly becoming.

RACIAL ORDER, MACHINE ORDER

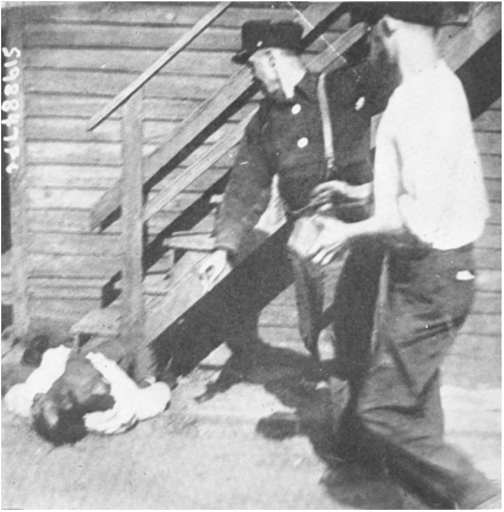

On a stiflingly hot Sunday at the end of July in 1919, the racial tensions that had been simmering since the stockyards strike of 1904 boiled over into a massive race riot that had people across the city throwing around the expression “race war.” Fittingly, the whole affair began at the lakefront, the very place whose blue watery vistas, Burnham had believed, would inspire “calm thoughts.” What transpired on the strip of sand between 25th and 29th Streets on July 27 was anything but serene. While differing accounts exist as to what sparked the week-long rampage of rage, violence, and arson, there is general agreement on three related events that occurred that day. The first concerned several African Americans daring to cross the imaginary color line in the sand to cool themselves in water fronted by a beach whites believed was reserved to them—an act that earned them a shower of rocks hurled by white beachgoers. The second, later in the day, involved a young white man in the breakwater around 26th Street lobbing rocks at three black teens on a makeshift raft, striking one of them, Eugene Williams, in the head and sending him to the bottom of the lake to his death. The third witnessed a mob of African Americans confronting police for refusing to arrest the man who had allegedly thrown the rock that had struck Williams, a situation that led to an exchange of gunshots that left a police officer wounded and the civilian shooter dead. These were the first two casualties of a frenzy of homicidal violence that, in the final toll, left thirty-eight people dead, some five hundred wounded, and thousands homeless. Some notable incidents were reported in the Near West and Near North Sides, but the area around the stockyards was ground zero.

FIGURE 2. Homicidal violence around the stockyards during the 1919 riot. Photo by Jun Fujita. From The New York Public Library.

While the magnitude and duration of the explosion shocked many, few were particularly surprised. Two years earlier Chicagoans had read about the horror and bloodshed of a similar race riot downstate, in East Saint Louis, Illinois, and the local press made sure that nobody missed the point that it could happen here. Appearing next to coverage of the aftermath of the East Saint Louis riot in the Chicago Tribune’s edition of July 8, 1917, for example, was one story with the provocative headline “Half a Million Darkies from Dixie Swarm the North to Better Themselves” and another reporting on former Illinois governor Charles Deneen’s suggestion that city authorities close the Black Belt’s “saloons, vicious cabarets, disorderly houses . . . as a safeguard against riots and mobs.” “Conditions in East Saint Louis,” the story made sure to point out, “were not unlike those prevailing in Chicago.”37 And there was certainly some truth to this. The series of events that had unraveled at the lakefront that scorching July day were perfectly consistent with general trends that had made Chicago into a tinderbox of racial conflict in the years leading up to the riot. In short, working-class white Chicagoans were becoming much more prone to lashing out against their African American neighbors and coworkers, and African Americans were becoming much more willing to resist and confront such aggression. In the past, collective acts of racial violence had crystallized mostly within the context of labor conflicts. But the scene at the lakefront revealed a new pattern of racial struggle over neighborhoods and recreational spaces that was becoming increasingly apparent as the city’s black population grew, and with it the determination of African American residents to assert their rights to the city’s spaces and resources. Further exacerbating the situation was the fact that the forces of order often refused to protect the rights of blacks, and, in some instances, actively aided white aggressors in their campaign to defend their neighborhoods against what they viewed as “black invasion.”

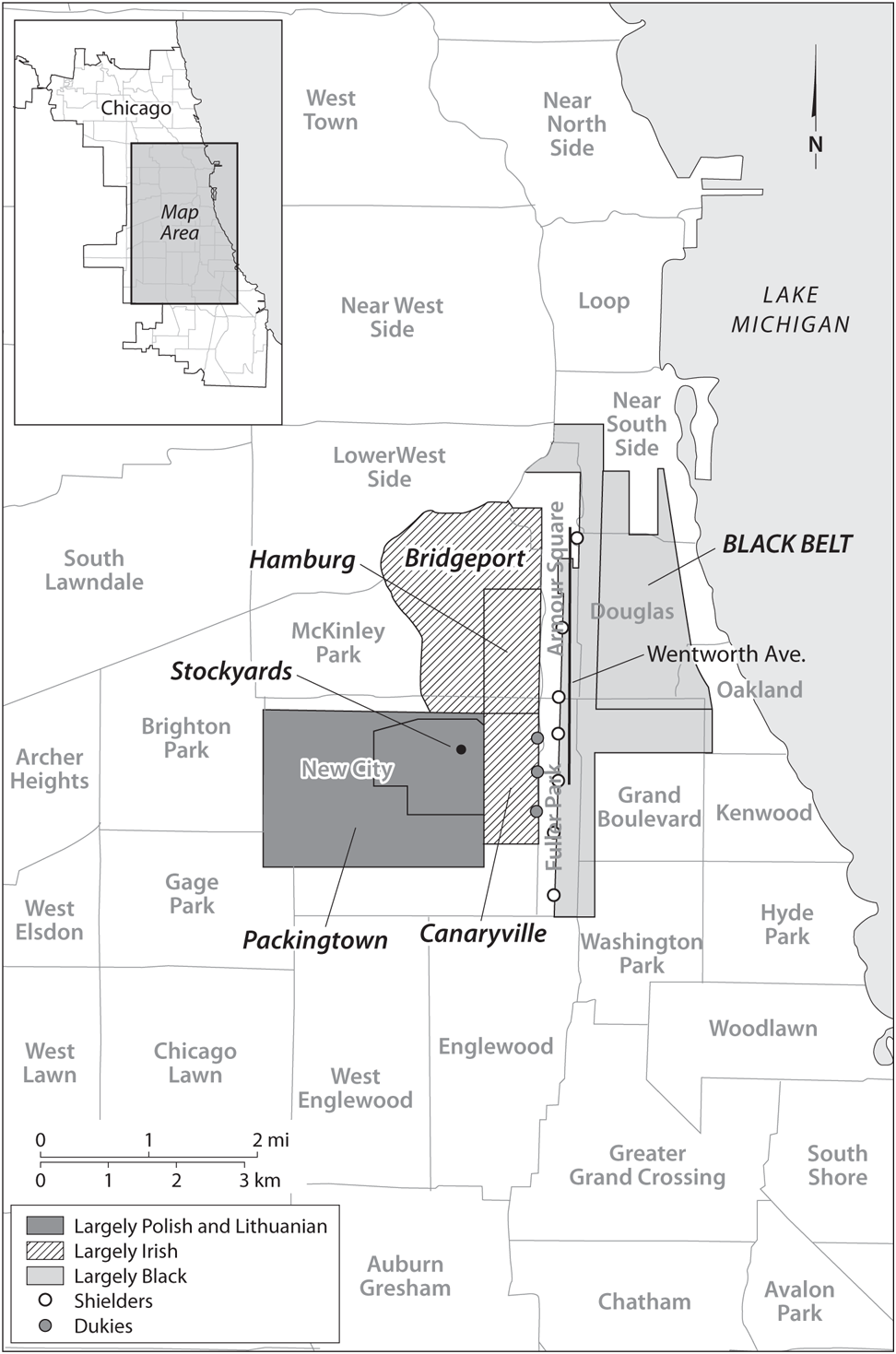

This volatile mix of circumstances came together with the entrance of the United States into the First World War, which opened up unprecedented opportunities for blacks in the industrial workforce. In part due to the efforts of labor recruiters operating in the Deep South, over fifty thousand black migrants arrived in the city between 1916 and 1919, roughly doubling the city’s black population.38 Many of them had expected to find a friendlier racial climate up North, but such hopes were quickly dashed. Mingling with such frustrations, moreover, was a new sense of assertiveness and wounded pride on the part of black veterans returning to the city after risking their lives for their country in combat overseas. These conditions produced a new wave of racial violence around the boundaries of the South Side Black Belt, which in 1915 consisted of a quarter-mile-wide band running along State Street from 12th Street down to 39th Street and edging southward. Between July 1, 1917, and July 27, 1919—the first day of the riot—whites in neighborhoods bordering the Black Belt bombed twenty-four black homes and stoned or otherwise vandalized countless others.39 The main perpetrators of such terror were young men organized into street gangs and so-called athletic clubs based in the Irish neighborhoods to the east of the stockyards. The most notorious of these organizations was Ragen’s Colts, a club that provided muscle for Democratic Cook County commissioner Frank Ragen and boasted of having some two thousand members. Such groups, according to a study of the riot’s causes by the Chicago Commission on Race Relations (CCRR), were instrumental in escalating the conflict and spreading it from the lakefront into the neighborhoods around the stockyards and the Black Belt. By the time of the riot, Irish gangs such as the Dukies and the Shielders claimed affiliates in a long stretch of city blocks from around 22nd Street all the way down to 59th Street, constituting a phalanx of hard-nosed street toughs bent on punishing any African American who dared cross the “dead line” of Wentworth Avenue and venture into the Irish neighborhoods of the Bridgeport area, Hamburg and Canaryville, which lay between the Black Belt and the stockyards. In the months preceding the riot, the antiblack intimidation carried out by these groups was so persistent and the sense of Irish pride motivating it so marked that, as historian James Grossman has noted, “many blacks mistakenly assumed that all the white gangs were Irish.”40

MAP 2. Communities, gangs, and boundaries on the South Side, ca. 1919.

Historians have generally agreed that Irish participation in the riot was strong, and more recent interpretations have put forward rather compelling evidence that some of the eastern European groups around the stockyards—Poles, Lithuanians, Czechs, and Jews—were reluctant to join in the hostilities, even at times comparing the attacks on blacks to forms of discrimination visited upon them by the Irish and other “Americans.” For example, Arnold Hirsch’s survey of a range of foreign-language newspapers—Polish, Lithuanian, Jewish, and Italian—in the period following the riot turned up a number of editorials that viewed the violence against African Americans as another ploy by the bosses to break the unions.41 Such findings could be interpreted as running counter to the idea that the Irish served as Americanizers for southern and eastern Europeans occupying a racially in-between status during the interwar years. Why indeed would the aristocracy of the stockyards and streets feel the need to engage in such demonstrative and risky acts when they seemingly had little to prove, and why would the groups whose status in the racial order was most precarious refrain from following the example of their standard-bearers as a means to reaffirming their whiteness?

As for the matter of antiblack aggression on the part of the Irish, the explanation has perhaps more to do with the injuries of class than with the circumstances of race, though the two factors were of course hard to disentangle in interwar Chicago. Certainly recent political events had stirred up racial animosities. Only four months prior to the riot, Republican mayor “Big Bill” Thompson had won his reelection bid in a tight race with strong support from black voters. “NEGROES ELECT BIG BILL” was the headline of the Democratic rag The Chicago Daily Journal on the eve of election day—a proclamation that elicited palpable outrage in Irish Bridgeport. That Thompson was a Republican was bad enough, but this particular Republican also displayed anti-Catholic tendencies in a moment when such tendencies were on the rise. Moreover, this slap in the face came at a time when working conditions around the stockyards were clearly deteriorating in the midst of the postwar recession everyone had feared. With the packinghouses laying off some fifteen thousand workers in the spring of 1919, employers looking to speed up the pace of production, and workers fearing competition from the tens of thousands of African Americans arriving in the city, tensions moved from the killing floors into the communities of Canaryville and Hamburg.

Canaryville and Hamburg were, in fact, separate neighborhoods with somewhat distinct and at times even rival identities. While each was home to families of packinghouse workers and industrial laborers, Hamburg, which extended from 31st to 39th Street between Halsted Avenue and the Penn Central Railroad tracks, had a leg up over its southern rival, which, with its western edge along Halsted between 39th and 49th Streets, offered too little distance from the smoke and odor of the stockyards. Canaryville was also too close to the increasingly overcrowded Back of the Yards (or Packingtown) area to the west of the stockyards, with its decrepit two-story wood-frame tenements packed with the Polish and Lithuanian immigrants whom Irish Bridgeport’s experienced meat cutters and butcher workmen commonly accused of undercutting their wages. Such conditions produced a street subculture that turned teenagers into career criminals—the Canaryville School of Gunmen, as it was referred to.42

Hamburg was also hard-boiled, but it was more akin to the Bridgeport that would produce three mayors and numerous other political, civic, and business leaders out of the generation of 1919. One of these was the future “Boss” of Chicago, Richard J. Daley, who used the strict guidance provided by the Our Lady of Nativity Parish School and then the commercial orientation of nearby De La Salle High School to help him ascend the ranks of the city’s political machine to the mayor’s office. Yet when not in the classroom or at his summer job in the stockyards, the young Richard Daley was running with the Hamburg Athletic Club, an organization which, as Mike Royko opined, “never had the Colts’ reputation for criminality, but [was] handy with a brick.”43 Like Ragen’s Colts, the Hamburgs furnished muscle for neighborhood bosses, and, as such, represented a quasi-legitimate opportunity structure. In 1914, for example, the president of the Hamburg Club, Tommy Doyle, used the club’s leverage to unseat an alderman who had held the position for over twenty years. Four years later, Doyle won a seat on the state legislature, and another Hamburg president, Joe McDonough, took over as alderman. Daley became the club’s president in 1924 and held the post for fifteen years while climbing the ranks of the Democratic Party machine.

While Canaryville was much less capable of producing this kind of political clout, what it lacked in political and social capital it made up for with syndicate ties. Questioned by the CCRR about this particular neighborhood, the state’s attorney of Cook County claimed that “more bank robbers, pay-roll bandits, automobile bandits, highwaymen, and strong-arm crooks come from this particular district than from any other.”44 Canaryville was the breeding ground for some of the city’s most notorious beer-running gangsters—people like “Moss” Enright, “Sonny” Dunn, Eugene Geary, and the Gentleman brothers—who drew much of their manpower from the pool of ready labor provided by the athletic clubs. The Chicago Crime Commission well understood this vital link between the crime syndicates and Canaryville’s gangs, reporting in 1920: “It is in this district that ‘athletic clubs’ and other organizations of young toughs and gangsters flourish, and where disreputable poolrooms, hoodlum-infested saloons and other criminal hang-outs are plentiful.”45

Criminal enterprises and machine politics thus offered some significant opportunities for young men in Canaryville and Hamburg, but there were not nearly enough to go around, and most of those coming of age in these neighborhoods were more proletarian than slick. Athletic club toughs were predominantly the sons of packinghouse workers and factory laborers, and the world they made on the streets was intimately linked to the affairs of the enormous meat-processing combine next door. Examining this world in the 1920s, sociologist John Landesco concluded that “the sons of Irish laborers in the packing houses and stockyards” joined gangs like the Ragen’s Colts because “Americanization made them averse to the plodding, seasonal, heavy and odoriferous labor of their parents, beset with the competition of wave upon wave of immigrants who poured into the area and bid for the jobs at lesser wages.”46 In reality, it was perhaps as much Taylorism as Americanism that made the Irish youths of these neighborhoods unwilling to cast their lots in a career in the stockyards and killing floors: as packers sought to keep up with increasing demand, they quickened the pace of work, maintained closer supervision, and introduced division of labor and continuous-flow production methods.47 Upton Sinclair’s description of a packinghouse perhaps conveyed it best: “a line of dangling hogs a hundred yards in length; and for every yard there was a man, working as if a demon were after him.”48 Such was the nature of the work available to unskilled youths in this moment. Moreover, a job wrestling with hog carcasses in a room like the one Sinclair depicted would have meant working side by side with Poles, Lithuanians, or members of other new immigrant groups whose status, many of the Irish believed, was clearly below theirs.

Conditions of this sort explain a great deal about why Irish youths coming of age around the stockyards district in the first few decades of the twentieth century were eager recruits for the race war that broke out in 1919. To be an aristocrat in the stockyards was not what it used to be, and the unwillingness of these youths to fill degraded jobs in the increasingly rationalized mass-production workplaces of the city ultimately stemmed from their understanding that other options were open to them—a situation that reflected the strong if embattled position of the Irish in the public sector. This was a large part of the “Americanization” that sociologists noted about them, and it was something that distinguished them from their immigrant neighbors, who had little choice in the matter of their employment in tedious, dangerous, low-wage labor. Yet for many working-class Irish youths, this perception of choice was something of an illusion. In fact, the Irish youths of the generation of 1919 were not so far removed from the American Protective Association’s “no Irish need apply” campaign of the 1900s, and they were now facing four more years under an anti-Catholic mayor who would certainly not be smothering this Democratic stronghold with patronage. Institutions like Daley’s alma mater De La Salle were beginning to show the sons of Irish packinghouse workers the way to the white-collar world, but those enrolled in such schools were still a rather select group. If Irish Bridgeport was in the process of producing an illustrious cohort of political and business leaders, few growing up in Canaryville and Hamburg were very aware of it.

Such circumstances shaped the youth subculture of gangs and athletic clubs that served as the training ground for the white foot soldiers of the 1919 race riot. Politicians and syndicate kingpins circulated in this milieu, drawing upon neighborhood muscle to rally votes and intimidate rivals, but the brutal rituals of street violence that were so central to this world served other needs. The culture of physical combat that defined the athletic clubs of Hamburg and Canaryville represented a collective strategy of the disempowered to create a compensatory system of empowerment. As in nearly all male-dominated, fighting gang cultures that have been studied by historians and sociologists before and after this historical conjuncture, claims to vital manhood and the sense of honor or status it bestowed constituted the stakes of the street brawls in this area. “Status as a gang among gangs, as well as in the neighborhood and the community,” Frederic Thrasher observed after surveying more than 1,300 Chicago gangs, “must . . . be maintained, usually through its prowess in a fight.”49 No other neighborhood area personified this idea more than the blocks of Hamburg and Canaryville, where demonstrations of “prowess in a fight” had been integral to the street culture since at least the 1880s. According to one resident, youths from these communities “thirsted for a fight,” and Saturday night turf battles between “Canaryvillains” and “Hamburg lads” often produced “broken noses and black eyes that were . . . too numerous to count.”50 And in a period when handguns were rarely used in such street fights, the not infrequent fatalities came the hard way: from skull fractures and stab wounds. The fact that gangs arriving at designated fights during these years expected to see their enemies holding clubs, bats, blackjacks, and knives that they were not afraid to use suggests that the drive for manly prowess was anything but trivial—rather, it was something worth risking one’s life for.

Although lads from Hamburg and Canaryville were perfectly willing to crack each other’s skulls for the sake of honor and respect, they preferred the skulls of the outsiders who seemed to be closing in on them from all sides—namely, blacks from across the color line and Poles and Lithuanians from the Back of the Yards. In the years leading up to the riot, social workers associated with the University of Chicago Settlement directed by Mary McDowell recorded a pattern of violence between Polish and Irish gangs in this area. One Polish gang in particular, the Murderers, engaged in recurrent brawls with a nearby Irish gang named the Aberdeens, whose members, according to one of the Murderers, “was always punching our kids.” A similar rivalry existed between another Polish gang of this vicinity, the Wigwams, and Ragen’s Colts, who on more than one occasion destroyed the Wigwams’ clubhouse at 51st and Racine, in the midst of a predominantly Polish area around Sherman Park. Apparently, when the Wigwams were unavailable for a beating, any Polish gang would do for the Colts, who, according to Polish residents in the area, cruised the area around Sherman Park, which lay right between Canaryville and Packingtown, looking for fights.51

Such battles, to be sure, were enmeshed within a process of Americanization in the streets that taught Poles and also Lithuanians the meaning of their “Polishness” within the city’s racial order. While Lithuanians represented about 29 percent of the population of the Back of the Yards, their Irish aggressors tended to lump them with Poles, who, with a 43 percent share of Packingtown’s population, dominated the neighborhood. And yet this process of Americanization did not have the effect—at least not yet—of bringing Poles and Lithuanians into a pact of whiteness with the Irish. While University of Chicago Settlement workers did observe the Murderers joining the offensive against African Americans during the riot and then later boasting about it, many Poles chose a place on the sidelines and some criticized the Irish for their actions.52 When an arson fire during the riot left about a thousand Polish, Lithuanian, Czech, and Slovak residents homeless, many in the Back of the Yards claimed the Irish had set the fire in order to rouse Poles and Lithuanians to action. Although we will never know the verity of the rumor that whites in blackface were seen running from the scene as the flames grew, that many believed the story to be true is nonetheless suggestive. And yet, if many southern and eastern Europeans largely refrained from joining the white mob, they showed no signs of actively defending blacks or of engaging in any form of meaningful cooperation with them. If their visceral contempt for the Irish and an awareness of their own injuries of race kept them somewhat neutral during the riot, the injustices imposed from above turned them against rather than towards those below them—as has so often been the case in the American experience.

As Arnold Hirsch has convincingly argued, substantial evidence from the 1919 race riot reveals how new immigrant groups—Poles, Lithuanians, Italians, and Jews, among others—occupied a “third (or middle) tier” within Chicago’s racial order at this time.53 But the riot itself was also a watershed event in the undoing of this very same racial order—a spectacular demonstration of the new centrality of the ghetto in the city’s political culture. The “third tier” did not disintegrate immediately, however. In the early 1920s, pop eugenicist Madison Grant’s theories about “Nordic” (northern European) racial superiority were orienting the national debate on immigration policy, and Prohibitionists across the country were decrying the wayward social habits of new immigrants.