TWO

Black Metropolis

ADVANCING THE RACE AND GETTING AHEAD

During the first weekend of April 1938, more than 100,000 black Chicagoans packed into the Eighth Regiment Armory in the heart of the Bronzeville district to behold the fruits of black enterprise displayed at the Negro Business Exposition. Those attending the exposition, as Time magazine reported, were there to “watch fashion shows, finger fancy caskets, see demonstrations of pressing the kink out of Negro hair, listen to church choirs and hot bands, munch free handouts or purchase raffle tickets from the 75 booths.”1 The event attracted the attention of the national news media because it signaled Chicago’s emergence as the capital of black America. “Although Chicago has 100,000 fewer Negroes than New York,” the Time story began, “it is the center of U.S. Negro business; last census figures showed Chicago’s Negro establishments had annual net sales of $4,826,897, New York’s were only $3,322,274.” And of course the article did not miss the opportunity to insert the kind of condescending remark that was so characteristic of the white gaze upon black attempts to “uplift the race”—in this case a jibe about the “admiring pickaninnies” surrounding world heavyweight champion boxer Joe Louis in a ploy to get the dollar bills that his bodyguard apparently gave out “to moppets so they will leave Joe alone.”2

Organized by a group of local businessmen and religious leaders, the Negro Business Exposition was part of a broader campaign that had picked up momentum in the midst of the Great Depression to promote support for black businesses as a means of “advancing the race.” Speaking on Sunday to an admiring crowd, one of the event’s key organizers, Junius C. Austin, the animated pastor of the famed Pilgrim Baptist Church (whose musical director Thomas A. Dorsey was at that very moment creating Chicago’s blues-inflected gospel sound), issued a declaration that left little doubt about what had motivated the exposition: “Tomorrow I want all of you people to go to these stores, have your shoes repaired at a Negro shoe shop, buy your groceries from a Negro grocer, patronize these Jones Brothers, and for God’s sake buy your meats, pork chops and yes, even your chitterlings from your Negro butcher.”3 Austin’s unabashed huckstering revealed that morale among black businessmen, eight years into the Great Depression, was at a low point. There were reasons to be hopeful—economic conditions had been picking up since the previous year, and the city’s biggest syndicate kingpins, the Jones brothers, had invested some of the countless nickels and dimes they had procured from black Chicagoans chasing winning numbers in their illegal “policy” lotteries to open the country’s largest black-owned retail establishment, the Ben Franklin store, in the heart of the Bronzeville business district. But if Austin’s exhortation to “patronize” the Jones brothers suggested that African Americans could still look to their business leaders—regardless of the nature of their enterprises—as beacons of hope, the idea of the black businessman as a “race man” was desperately in need of reinforcement. Just two months prior to the exposition, former business magnate Jesse Binga, the founder of Chicago’s first black-owned bank and thus a great symbol of racial progress, had been released from prison after serving five years for embezzlement—a broken man who would live out his life working as a janitor and handyman.

After observing the boosterism of black businessmen around the Negro Business Exposition, St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton, the illustrious black scholars and authors of the definitive study of black life in interwar Chicago, Black Metropolis, issued a sober rejoinder to those who still sought to measure black progress “in terms of the positions of power and prestige which Negroes attain in the business world”:

No Negro sits on a board of directors in La Salle Street; none trades in the grain pit or has a seat on the Stock Exchange; none owns a skyscraper. Negro girls are seldom seen in the offices and stores of the Loop except as maids. Colored traveling salesmen, buyers, and jobbers are a rarity. The largest retail stores and half of the smaller business enterprises in Bronzeville are owned and operated by white persons, and until recently many of these did not voluntarily employ Negroes.4

Drake and Cayton compiled numerous figures to back up this assessment, the most striking of which showed that while black enterprises constituted nearly half of all the businesses in black Chicago, they received less than 10 percent of all the money spent within these areas. They also pointed out that the overwhelming majority of the some 2,600 black businesses in operation were small-scale enterprises—287 beauty parlors, 257 groceries, 207 barber shops, 163 tailors and cleaners, 145 restaurants, 87 coal and wood dealers, 70 bars, 50 undertakers, to name the most numerous—and they were located “on side streets, or in the older, less desirable communities.”5

This vision of the decrepit state of the black business community contrasted somewhat with the overall picture these scholars painted of the impressive “Black Metropolis” that had developed around the Bronzeville district, with its bustling shopping area around 47th and South Parkway (now called King Drive), where the Ben Franklin store had opened its doors amidst much fanfare. Here, they pointed out, black Chicagoans could look upon an array of powerful and proud black institutions: “the Negro-staffed Provident Hospital; the George Cleveland Hall Library (named for a colored physician); the ‘largest colored Catholic church in the country’; the ‘largest Protestant congregation in America’; the Black Belt’s Hotel Grand; Parkway Community House; and the imposing Michigan Boulevard Garden Apartments for middle-income families.”6 Chicago’s Black Metropolis had become a veritable city within a city in the 1910s and 1920s, when nearly 200,000 black migrants took up residence within its borders, raising the total black population to just under 234,000. This influx of migrants transformed black Chicago, creating a “negro market” for goods and services and with it new forms of black market consciousness, which by the 1920s were intermingling with black nationalist currents circulating around Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) and the New Negro ideology emanating from the Harlem Renaissance. In this context, ordinary African Americans began to see in black purchasing power the promise of racial uplift, if not liberation, and looked towards an emerging generation of business magnates as the quintessential “race men”—a situation that caused great concern among the political forces of racial progress, from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League to the Communist Party.

Certainly Drake and Cayton’s gloomy assessment of black business stemmed, in part, from the concern being voiced by some political leaders that the allure of individual success in the business world could dampen support for collective strategies of racial struggle in the political sphere. Garveyism had sought to reconcile the gospel of private enterprise with more cooperative notions of racial progress throughout the 1920s, but the marriage of these ideals had come under considerable strain during the lean years of the Great Depression, even after the Don’t Spend Your Money Where You Can’t Work boycott of 1930 had demonstrated to black Chicagoans that they could use their buying power to force a national chain store like Woolworth’s Five and Ten to change its discriminatory hiring practices. Triumphant as it was, the campaign had failed to blossom into a broader movement, and perhaps more significantly for the black business community, it had failed to alter the daily spending habits of Bronzeville residents. While black businessmen generally ascribed the continuing black predilection for patronizing white-owned businesses to the power of “the white man’s psychology” learned in the South or else to some desire to magically invert the racial order by using their purchasing power to place whites in a subservient position, many working-class blacks referred merely to the lower prices and better services offered by white merchants.7

But Drake and Cayton’s skepticism was also due to the fact that from the vantage point of the late 1930s and early 1940s, when they were collecting their data, black businesses were hardly thriving. If, as historian Christopher Robert Reed has claimed, the 1920s was the “golden decade of black business,” many of the grand achievements of this era had been erased during the Depression years.8 Black Chicago’s banks had gone belly up, and its mighty business leaders had been brought down to size. In fact, by the time Black Metropolis was released in 1945, each figure in Chicago’s triumvirate of black business heroes had been leveled in one way or another. Binga was working as a janitor; Robert Sengstacke Abbott, the founder of the Chicago Defender, the most widely circulated black newspaper in the country, was dead; and Anthony Overton, who in the 1920s had parlayed the revenues from his Overton Hygienic Company into a conglomerate that included the Douglass National Bank, the Victory Life Insurance Company, and a black weekly newspaper called the Chicago Bee, had reverted to his role as a seller of brown face powders.

And yet, even though the Great Depression had certainly humbled black businessmen and many of those who entrusted them with the future of the race, the crowds that packed into the Negro Business Exposition demonstrated that the gospel of black capitalism was relatively unshakable among ordinary residents of Bronzeville. This was due in part to the fact that the exclusion of blacks from trade unions and their relegation to low-wage, often dangerous jobs unleashed the spirit of entrepreneurialism in the Black Metropolis. Utilizing occupational data gleaned from a New Deal–funded study on the black labor market in Chicago, Drake and Cayton painted a grim picture of a black population constrained by an impossibly low “job ceiling.” Out of some 123,000 blacks in the workforce in 1930, 75,000 (61 percent) worked unskilled and service jobs, while only 12,000 (less than 10 percent) performed professional, proprietary, managerial, and clerical jobs—what Drake and Cayton referred to as “clean work.” In fact, African Americans filled just 2 percent of all clean-work positions citywide, compared to 78 percent for whites and 20 percent for foreign-born immigrants. For black men, mail carriers (630) constituted by far the most common job in this category, followed by musicians (525), clergymen (390), and messengers and office boys (385); for women, restauranteurs (235) topped the list, followed by musicians (205) and actresses (145). As for the lower rungs of the occupational ladder, some 25 percent of all black male workers and 56 percent of all female ones were employed in some kind of servant work. For women, this mostly meant domestic service; for men, it involved a range of low-paying service jobs (janitors, elevator men, waiters, domestic service) as well as the relatively high-paying but somewhat demeaning job of Pullman porter (held by almost 14 percent of black male service workers). Black male manual laborers, for their part, were concentrated in the lowest paying and dirtiest unskilled jobs in factories, steel mills, and packinghouses, and black female manual laborers in poorly paid positions in laundry service and the needle trades.9

Starting one’s own business thus seemed well worth a shot when faced with the prospect of working in the foundry of a steel mill or on the killing floor of a packinghouse. Black’s Blue Book, black Chicago’s first business directory catered to this burgeoning entrepreneurial spirit, urging black Chicagoans to “find your vocation and follow it” and warning them to “expect nothing on sympathy, but everything on merit.”10 Between 1916 and 1938 the number of black-owned businesses in Chicago jumped from 727 to over 2,600, outpacing the robust growth of the black population. Moreover, these figures did not even take into account black Chicago’s most prevalent “business”: the storefront church, which, with well over three hundred lining the streets of Bronzeville, topped beauty parlors as the most numerous type of black enterprise in the city.11 During the Great Depression, according to Drake and Cayton, several hundred “jack-leg preachers” competed for pulpits in order “to escape from the WPA or the relief rolls”—a situation that resulted in a veritable “revolt against Heaven” by working-class churchgoers who accused their religious leaders of corrupting their spiritual lives or, more bluntly, of bilking them out of their money. As one congregant complained, “The average pastor is not studying the needs of his race. He’s studying the ways to get more money out of the people.”12

The stories concerning the iniquitous practices of some of the more entrepreneurially minded storefront preachers no doubt contributed disproportionately to the perception shared by many black Chicagoans that their churches were akin to rackets or businesses, but the larger, more established mainline Baptist and Methodist churches also engaged in practices that blurred the line between spiritual and monetary pursuits. By the early 1920s, with pews in Bronzeville packed with recently arrived southern migrants, many of the more prominent churches began building alliances with black businesses. “It was not uncommon for black churches to support black-owned businesses by carrying advertisements in their church bulletins and newspapers,” historian Wallace Best has argued, “or by encouraging members to patronize certain retail stores, grocers, doctors, barbers, and undertakers.”13 While such exhortations were justified by broader appeals to “advancing the race” through the promotion of black enterprise, pastors also understood that businessmen would reciprocate with donations. In the fall of 1923 a group of black businessmen led by Robert Abbott and Jesse Binga organized the Associated Business Club (ABC) of Chicago for the purpose of adding a secular voice to the chorus of preachers singing the praises of black capitalism. With its membership expanding from fourteen to nearly one thousand in its first year of existence, the ABC sought to harness the efforts of pastors throughout Bronzeville by offering a free trip abroad for the pastor who brought the most customers to ABC-affiliated businesses.14 Some fifteen years later, as Junius Austin’s spirited involvement in the Negro Business Exposition suggests, pastors and businessmen were still rallying around the hopes and dreams of the black economy, and many ordinary black folks still seemed to want to believe.

This alliance of pastors and businessmen explains a great deal about the staying power of a business ethos oriented around the ideas of thrift, self-help, and racial uplift popularized by Booker T. Washington and his Negro Business League in the early years of the twentieth century. Certainly churches had their detractors, but they nonetheless continued to touch the hearts and minds of black Chicagoans as much as any other institution in the community. Yet African Americans also continued to believe in racial salvation through business success because a great many of them had lived through the not-so-distant heyday of the Black Metropolis, and there was plenty of reason to think that what had befallen their community was not due to any failings of the race or of the system of black capitalism itself but rather to broader forces that had struck U.S. society at large. The aura of the Black Metropolis as a place of excitement, innovation, and pride—immortalized in the canvasses of Archibald Motley, the writings of Langston Hughes, and the sounds of Louis Armstrong’s trumpet—still lingered in the air.

For many, the promise of the Black Metropolis lay not in the rise of its vaunted black-owned banks, insurance companies, newspapers, and manufacturers but rather in the development in the 1910s and 1920s of the black entertainment district known as “the Stroll,” a segment of State Street stretching from 26th Street on down to 39th Street, where, as Langston Hughes famously remarked, “midnight was like day.” Here on the Stroll the bright glow emanating from countless cabarets, theaters, bars, and restaurants served as stage lighting for the swirling mass of black and white humanity jamming the sidewalks and spilling into the streets. The soundtrack was provided by the intermingling sounds of blues shouters, boogie-woogie piano romps, and hot jazz horn solos pulsating out of the numerous storefront jazz joints and cabarets. “If you held up a trumpet in the night air of the Stroll,” bandleader Eddie Condon once claimed, “it would play itself!” In the 1910s and 1920s, as Chicago was assuming its place as the nation’s leading center of heavy industry, the economy of its black city within was developing around the myriad commercial leisure ventures offered by the Stroll—its cabarets, nightclubs, dance halls, ballrooms, theaters, speakeasies, gambling halls, vaudeville houses, buffet flats, and brothels. By the late 1920s the Stroll began to decline rapidly, but its spirit migrated southward with the opening of the enormously successful Savoy Ballroom at 47th and South Parkway in 1927. In the early 1930s this area became the new bright-lights district of the Black Metropolis, and its happenings were, thanks to the publicity offered by the Chicago Defender, known to African Americans across the nation.

Such happenings did not figure into Drake and Cayton’s rendering of Bronzeville—somewhat astonishingly given Chicago’s importance as a fountain of Jazz Age black cultural expression. The omission suggests a lingering uneasiness among black middle-class civic leaders about black Chicago’s transformation into a playground of desire, pleasure, and exoticism in the interwar years, when entrepreneurs, a good many of them white, opened up a number of black-and-tan cabarets catering to white “slummers” seeking the thrill of hot jazz, bootlegged liquor, and the black sexuality on display on the dance floor.15 Even by the early 1940s, decades after Chicago’s Black Metropolis had clearly established itself as the nation’s “melting pot” of jazz and blues, its performing and recording scene helping to catapult the likes of Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Bessie Smith, Joe “King” Oliver, Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters, and Earl “Fatha” Hines to national prominence, a number of black community leaders were still unable to comfortably embrace this cultural heritage. This ambivalence stemmed from the fact that while many of the music venues of the Stroll were owned and run by blacks, they hardly embodied, in the eyes of many respectable civic leaders, the kinds of enterprises that contributed to “uplifting the race.”16 If the Stroll, according to historian Davarian Baldwin, “was more than simply a stretch of buildings, amusements, sidewalks, and signposts but the public showcase for black ‘expressive behavior,’” the dancing, shouting, shimmying, and frolicking that was being showcased there flew squarely in the face of the codes of respectability promoted by the older, more established middle-class elements of the community.17

As Baldwin has argued, although most in the Black Metropolis invested in some idea of economic nationalism, the interwar years witnessed a struggle between an “old settler” ideology oriented around hard work, thrift, and sobriety and a “new settler” ideology that viewed in the Stroll’s commercialized leisure enterprises the means not only to get ahead but also to create a new sense of racial pride and respectability.18 The clash of these ideals appeared frequently in the black press during this era. On May, 17, 1919, for example, the Chicago Defender justified publishing a list of dos and don’ts directed at recent migrants with the explanation: “It is evident that some of the people coming to this city have seriously erred in their conduct in public places, much to the humiliation of all respectable classes of our citizens, and by so doing, on account of their ignorance of laws and customs necessary for the maintenance of health, sobriety and morality among the people in general, have given our enemies ground for complaint.” Among the list of don’ts provided to the Defender by the Chicago Urban League were several explicitly targeting the Stroll nightlife: “Don’t encourage gamblers, disreputable women or men to ply their business any time or place”; Don’t congregate in crowds on the streets”; “Don’t spend your time hanging around saloon doors or poolrooms.”19

The Defender’s publisher, Robert Sengstacke Abbott, was the mouthpiece of the businessman race heroes of the daytime Stroll, who decried the pleasure-seeking and immorality that raged after nightfall. Abbott’s Stroll by day, referred to at the time as “the black man’s Broadway and Wall Street,” offered a very different vision of black pride and autonomy. Rising amidst its famed nightspots—Motts Pekin Theater, the Apex Club, Elite No. 1, Elite No. 2, the Dreamland Ballroom, the Sunset Café, and the De Luxe Café—were brick-and-mortar monuments to the promise of black capitalism: the hulking Binga State Bank at 3452 South State with its marble, bronze, and walnut interior and imposing steel vaults; the Chicago Defender building at 3435 South Indiana, headquarters of a newspaper that, while occupying a converted synagogue, had the audacity to herald itself as “the world’s greatest weekly”; and the Overton Hygienic Building at 3619–3627 South State, a massive six-story structure also housing Overton’s Douglass National Bank and Victory Life Insurance Company, which Overton himself hailed as “a monument of negro thrift and industry.”20 The owners of these structures unabashedly assumed the role of preachers in the church of black capitalism. Although these reputed self-made captains of industry had established their enterprises in earlier years—Abbott founded the Defender in 1905, Binga opened his first bank in 1908, and Overton established his cosmetics company in Chicago in 1911—their stars began rising in the aftermath of the 1919 race riot, when their words of wisdom about hard work, thrift, and economic nationalism as the antidotes to systemic white racism were spread all over the pages of the black press.

More than anyone else, Jesse Binga incarnated the figure of the businessman race hero of the 1920s, a legend that his associate Robert Abbott—a major stockholder in Binga’s bank—played a big part in creating. The Defender followed Binga’s every move, giving him regular front-page exposure, and Binga used the pulpit offered to him to deliver sermon after sermon about how black businesses, with the proper support from black consumers, would lead the way towards racial progress. Announcing that his private bank would soon be reorganized under the protection of a state charter in April 1920, for example, Binga spoke of “an undercurrent of forces at play . . . gradually forcing the people of the great south side into an insoluble mass, which is to result in inestimable financial strength and resources.”21 More than three years later, addressing the Associated Business Club (ABC), a group that included Abbott, Overton, and Claude A. Barnett, founder of the Associated Negro Press news agency, Binga was still hammering away at the same ideas. “I would say to those aspiring to be of influence in our community,” Binga asserted, “to remember that the banks and the business men are the bulwark of the community.” “A race to achieve its independence,” he proclaimed, “must foster its own interests.”22 Such sentiments were intended not only to position businessmen as race leaders but also to counter the idea, shared by a range of white opinion makers, that African Americans as a race were out of step with the spirit of modern capitalism. Famed University of Chicago sociologist Robert Park went so far as to refer to blacks as “the lady of the races,” attributing their deficiencies in the marketplace to temperament: “a disposition for expression rather than enterprise and action.”23 Although Park and many others of his ilk understood all too well that municipal zoning and law enforcement policies and the concatenations of machine politics—not any traits supposedly inherent in the race—had made the Stroll into a playground for gamblers, boozers, and sporting types in search of sexual adventure, the epic story of Chicago jazz, with all the artistic virtuosity and sensuality that came with it, seemed to confirm Park’s essentialization of blacks as cultural producers.

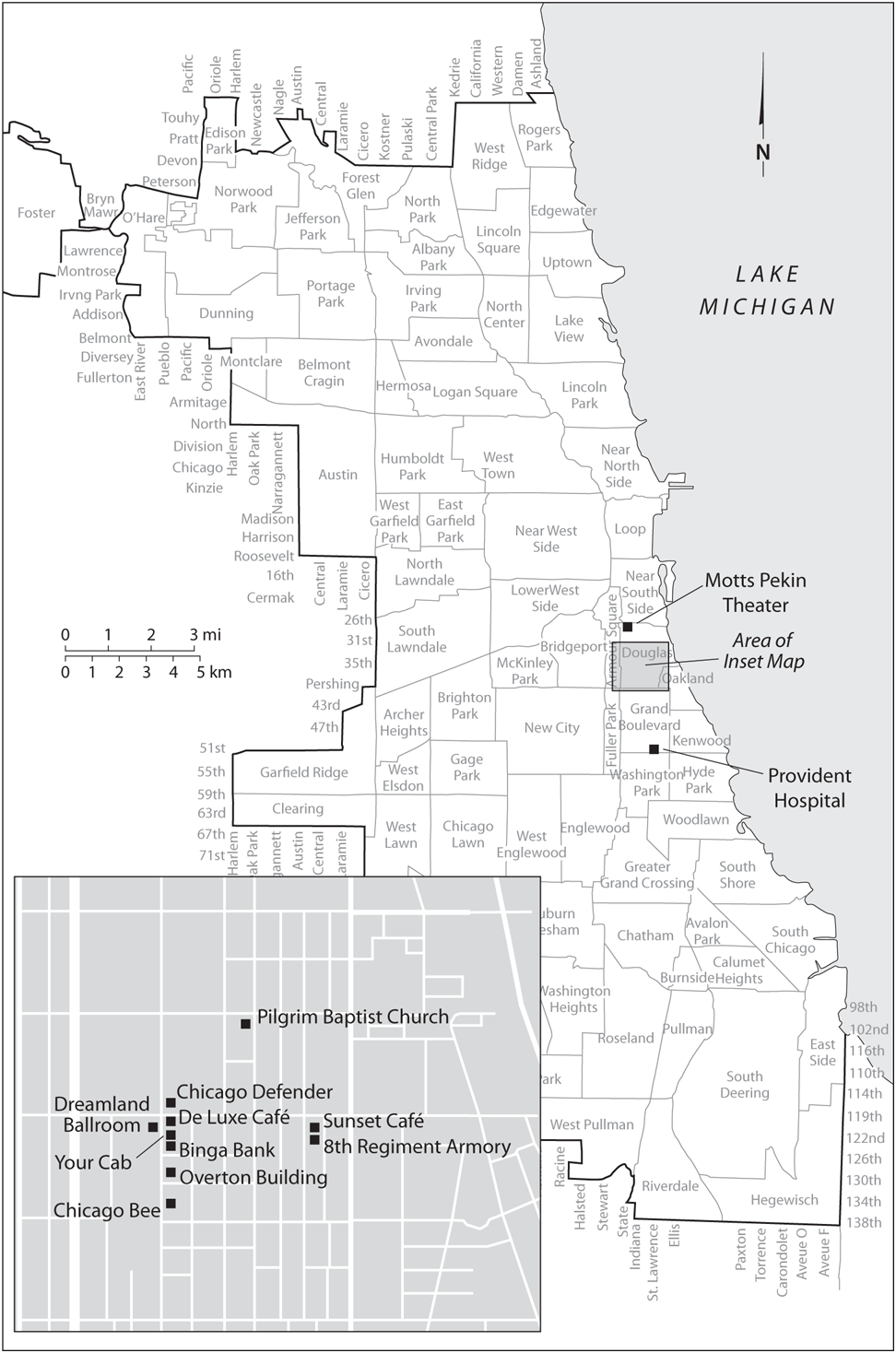

MAP 3. Bronzeville and the Stroll in 1920.

FIGURE 3. The Overton Hygienic Building at 3619–3627 South State Street. From The New York Public Library.

Binga and the ABC crowd were thus somewhat adamant about drawing a sharp distinction between the earnest enterprise of the daytime Stroll and the frivolous jouissance of its nighttime alter ego, but the connection between these two worlds was, in reality, hard to deny. For one thing, there was no getting around the fact that the action of the nighttime Stroll produced revenues for some of the most important black businesses. Abbott’s Defender may have stridently criticized the immoral ways of migrants cavorting on the Stroll, but it also profited enormously from showcasing these same activities. Amidst the Defender’s ads for the Stroll’s hottest clubs, moreover, could be found others for a range of beauty services and products—Overton’s face powders prominent among them—for revelers heading out for a night on the Stroll, and the burgeoning black-owned Your Cab Company at 3635 South State Street earned a good many of its fares from these same revelers. The activities of the daytime and nighttime Strolls were intertwined in other ways as well. As Davarian Baldwin has argued, “Better paying industrial jobs surely provided the disposable income for leisure activities, but it was the nickels and dimes used to buy drinks in local dance halls and put on lucky numbers at policy wheels that recirculated within the community to support the black metropolis.”24 It was, to be sure, hard to find a nickel or a dime in Bronzeville that had not touched the hands of a numbers runner. Brought to Chicago from New Orleans in the late 1880s by the legendary “Policy” Sam Young, policy wheels (illicit lotteries) multiplied rapidly in the high-paced atmosphere of the Black Metropolis, where, as Drake and Cayton claimed, a spirit of “getting ahead” joined that of “advancing the race” as one of the organizing axes of black life.

BY THE NUMBERS

By the late 1930s, the more reliable estimates had over 100,000 black Chicagoans placing some $18 million in bets at over 4,000 South Side policy stations, and while the policy syndicate was of course a pyramidal structure with limited redistributive possibilities (at least in a downward direction), policy wheels nonetheless provided thousands of jobs, and the profits they generated found their way into a range of legitimate ventures that created thousands more. Policy was thus the common denominator between the daytime and nighttime Strolls. Gambling and jazz (not to mention vice) were of course hard to disentangle on the nighttime Stroll, where policy kings underwrote the establishment of many of black Chicago’s most revered jazz venues—the Pekin, the Dreamland, the Apex Club, Elite No. 1, and Elite No. 2—and where smoky gaming rooms were often appendages of the halls where Chicago’s greatest musicians strutted their stuff. But policy proceeds lubricated the cogs of the daytime Stroll’s economy as well. Binga’s financial ventures, for example, were bankrolled in part by the gambling proceeds that passed into his hands through his marriage to Eudora Johnson, who had inherited more than half the substantial wealth of her brother, legendary policy kingpin John “Mushmouth” Johnson, upon his death in 1907.

The impact of policy could be felt in nearly every corner and alley of the Black Metropolis. Policy wheels offered supplemental revenue to beauty parlors, grocery stores, bars, and even funeral parlors, and many such legitimate businesses were built upon the nickels and dimes of its players. For example, in 1925 undertaker Dan Jackson, the “general manager” of the South Side’s most powerful vice and gambling syndicate, used the profits from his illicit operations to launch the Metropolitan Funeral System Association—a thriving business that offered burial insurance to working-class black families for a fifteen-cent weekly premium. Two years later he sold it to another gambling kingpin, Robert Cole, who used his own profits to develop a sister company, Metropolitan Funeral Parlors, and move it into a modern office building he built at 4455 South Parkway in 1940. While Cole was no doubt looking to make a buck, this particular business venture aligned financial motives with more noble ideals. Denied proper funeral services by white undertakers, bereaved African Americans faced the humiliation of not being able to procure a respectable funeral, a situation that transformed Cole, whose companies offered insurance and burial services, into another of Bronzeville’s self-made businessman race heroes. Yet Cole’s contributions to the cause of black respectability did not stop at the funeral parlor. Beginning in the 1930s, he invested his financial resources in a number of visionary cultural ventures, providing office space for the pioneering All-Negro Hour radio show, the first to feature black performers exclusively, founding a popular black magazine called the Bronzeman, and purchasing the Chicago American Giants Negro League baseball team in 1932. Jackson served as Second Ward committeeman after helping Big Bill Thompson procure more than 91 percent of the black vote in his victorious 1927 mayoral election bid. As committeeman, he steered hundreds of thousands of graft dollars each year into Thompson’s machine, assuring that South Side gambling operations would continue to irrigate the economy of the Black Metropolis.

The fact that policy wheels undergirded the financial, cultural, and political infrastructure of the Black Metropolis made many of the champions of middle-class respectability somewhat reluctant to include policy among the litany of vices allegedly setting back the race. One study of the numbers game in interwar Harlem revealed that business leaders there claimed that the viability of the community’s policy banks had been critical in building business confidence among African Americans, and it is more than likely that such views were prevalent among business leaders in Chicago’s Black Metropolis as well.25 Moreover, the argument that policy provided thousands of jobs to black folks who were being denied employment in white businesses held plenty of water, transforming gambling kingpins into veritable race leaders. Bronzeville residents thus reacted with heated anger at the judgmental gaze of whites upon their alleged propensity to throw nickels and dimes at elusive numbers. The Chicago Defender was clearly seeking to channel such feelings of resentment, for example, during Mayor Cermak’s 1931 campaign to close down South Side policy wheels, when it published a series of editorials decrying the mayor’s characterization of a lawless “black belt,” where, Cermak reportedly claimed, “95 percent of colored people over 14 years old” played the numbers.26

To be sure, policy was a sensitive issue in the Black Metropolis. A range of black ministers and civic leaders railed against it, pointing at all the people reduced to destitution because of their addiction and sardonically mocking those who sought to profit from this addiction—the so-called spiritual advisors and peddlers of “dream books” promising to extract winning combinations from the shadowy depths of a gambler’s subconscious. However, such reproaches coming from the other side of the color line sparked the kind of outrage and proud defiance that made average residents of the Black Metropolis see heroism in the businessmen and syndicate kingpins who were exploiting them. For if policy was many things to many people, it was also a means of redistributing the increasing wealth of the Black Metropolis upward towards the point of the social pyramid, and, regardless of the numerous stories of winning “gigs” (three winning numbers out of twelve) pulling families out of tough circumstances, policy did, in fact, keep a good number of people down, though how many we will never know with any certainty.

But policy’s impact went far beyond the economic realm. The penetration of policy into the fabric of everyday life in the Black Metropolis also had undeniable consequences for the political culture, especially in terms of how average residents made meaning of the dramatic inequalities prevailing there and of the possibilities for addressing them. Although historians have grappled with the role of policy gambling within the economies and labor markets of black ghettos in the first half of the twentieth century, they have largely overlooked its ideological power.27 Policy was symptomatic of the conditions of life in the lower-class world of Bronzeville, and a good many of those who laid down their nickels and dimes for long-shot slips of paper lived in the impossibly cramped “kitchenette” apartments that proliferated on the South Side during the interwar years (figure 4). These one-room living spaces, which real estate developers hastily carved out of basements and larger apartments, with little concern for proper ventilation and plumbing, often housed as many people as could find a space on the floor to stretch their legs for a night’s sleep. “A building that formerly held sixty families,” Drake and Cayton claimed, “might now have three hundred.”28 Richard Wright referred to the kitchenette as “our prison, our death sentence without a trial, the new form of mob violence that assaults not only the lone individual, but all of us, in ceaseless attacks.”29 Yet, if Wright’s evocation of “mob violence” pointed to the white hand behind such conditions in northern ghettos like Harlem and Bronzeville, the ethos surrounding policy represented a countervailing force to such notions.

FIGURE 4. South Side kitchenette apartment. Photo by Russell Lee. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

To be sure, discerning the psychology of habitual gamblers is slippery ground, and few scholars dealing with such issues have sought to do so in the tight-knit cultural context of a place like the Black Metropolis of interwar Chicago. Nonetheless, it is hard to argue with the idea that the fatalism inherent in the ritual could only have worked to deflect attention from the structural circumstances behind the rampant poverty of the Black Metropolis, even if the ethos of black capitalism offered constant reminders that the misery and toil there were due to the exclusion of blacks from white society. Besides, when players lost enough to make them stop to think about who was profiting from all the nickels and dimes they threw down, their reflection led them not to the other side of the color line but to their own policy-king race heroes, whom they simultaneously begrudged and admired. This is not to say that policy did not offer something valuable. It was a ritual of sociability that provided daily amusement, and the sense of camaraderie around the game sometimes saw players pooling their winnings and more often commiserating over their losses. Moreover, in addition to their role as an employer, policy banks served as a vital source of loans at a time when credit was scarce. Nonetheless, playing the numbers on a daily basis infused the common sense of working-class blacks with powerful notions of chance and risk that individualized or otherwise explained away the difficult conditions they faced as matters of fate and hard luck. And there were enough self-made success stories around the Black Metropolis and in the pages of the black press to confirm such notions.

However, policy’s ideological force was not due only to the fact that it tended to normalize and legitimize the precariousness and risk that could have created, in the words of William Gamson, “the righteous anger that puts fire in the belly and iron in the soul”—the critical preconditions of political mobilization.30 For the more serious players, it is important to remember, policy was more an investment strategy than a game, and even the most leisurely players understood the speculative, calculating nature of the venture. And in this it resembled another form of speculative activity that spread through the Black Metropolis during this same era: the purchase of insurance policies to protect families against a disabling or deadly industrial accident or simply to guarantee a respectable funeral. In fact, many of the same rationalities were at play in the insurance industry as in the world of policy.

Insurance magnates like Anthony Overton and Robert Cole became race heroes in Bronzeville because they challenged the injustices blacks suffered in paying high premiums for coverage provided by white-owned companies, and in so doing they created decent jobs for the African Americans staffing their expanding workforces. The client base of Cole’s Metropolitan Funeral System Association (MFSA), for example, grew from 33,000 in 1935 to 52,000 by 1939, an increase that made MFSA a source of jobs when most firms in other sectors were scaling back. And, like policy kingpins, the captains of the insurance industry capitalized on their role as race men to maximize their profits, organizing boycotts of white insurers and advertising their contributions to the race on billboards and in the pages of the black press. Yet, after interviewing a number of prominent insurance men and Bronzeville residents, Drake and Cayton painted a grim picture of Bronzeville’s insurance business, including executives speaking cynically and candidly about exploiting their capital of race pride to sell policies, and burial insurers working hand in hand with undertakers to provide minimal funeral services at exorbitant prices—a practice that continued even after state legislation to address the problem was supposed to have required insurers to pay their bereaved clients in cash.

Insurance, like policy, was of course an upwardly redistributive scheme, even if it did help some to make do under difficult circumstances. There was good reason that funeral parlors often served as policy stations, and that people like Cole and Jackson moved seamlessly between the worlds of policy wheels and insurance policies. But, like policy, the impact of the insurance business on the Black Metropolis went far beyond the economic realm. “Insurance’s general model,” François Ewald has written, “is the game of chance: a risk, an accident comes up like a roulette number, a card pulled out of the pack.”31 In the context of the interwar Black Metropolis, the insurance “game” was thus another activity that tended to cast the effects of structural inequalities as random events devoid of political meaning. Moreover, unlike the labor union or mutual aid society, insurance represented an individualized and privatized response to problems that might have otherwise been perceived as collective and public. The rationale that went with insurance transformed social injustices into “accidents,” deflecting attention away from the reasons why African Americans in Chicago in the 1920s died at twice the rate whites did. Insurance, like policy, imposed a market logic on the affairs of everyday life, and all of the energy that black insurers put into organizing boycotts and emblazoning billboards with the promises of racial uplift suggested that the sense of “linked fate” they were offering with their policies was something of a hard sell.32

The explosion of policy and insurance in the 1920s thus reflected the ways in which the hegemony of black capitalism was working to “economize” the political culture and everyday life of the Black Metropolis.33 How else to explain Jesse Binga’s astonishing 1922 telegram to the secretary of the Illinois Bankers Association, published approvingly in the pages of the Chicago Defender, which, in urging “stronger ties of cooperation between the two races,” boldly offered up black Americans as a resource to be better exploited:

The Negro is an industrial people. He furnishes two-fifths of the brawn and muscle of America: our wages return to whomsoever has the proper equivalent for those wages. You may get the Negro’s dollar, but the question is, are you getting all you should from the Negro?

Should we not utilize to the extent of reaping millions out of him instead of getting merely thousands? Should we not develop the Negro in his desire for economic happiness to the extent of rendering his possessions worth a million instead of a thousand? That means more for your bank and for all the business institutions dependent upon it.

I admit that the Negro is not fully developed in business. He is at the same stage that your ancestors were during the opening of the Victorian era: but he is today the most promising undeveloped commercial material in America.34

Nor was this vision of the black population as a raw material for economic exploitation merely a rhetorical device for Binga and the business elite he spoke for; it was an idea that was put into practice in the ruthless pursuit of wealth in both the underground and formal economies of the Black Metropolis. In addition to marrying into policy money, Binga also gained some of his wealth in the real estate market. And, although he would build up his résumé as a race leader in the 1920s by using blockbusting tactics to open up formerly all-white areas for African Americans in desperate need of housing, Binga’s business plan ultimately revolved around exploiting the people he was supposed to be uplifting. Instilling panic in white owners fearing the racial “invasion” of their neighborhoods, Binga was able to procure apartments in white-occupied buildings by offering a big advance to the owners on the rents, but, as was common practice among black real estate developers of the time, he then divided them up into kitchenettes and rented to poor black families at a sizable premium over the market price paid by white renters on the other side of the color line. The “boss” of the South Side’s black “submachine,” Oscar DePriest—who became the first African American elected to Chicago’s city council (as Second Ward alderman) in 1915 and then the first black politician elected to the House of Representatives from a northern state in 1928—engaged in similar practices while amassing a personal fortune as a real estate broker. DePriest rose to prominence both locally and nationally as a race leader by defending the rights of African Americans on the floor of the House of Representatives, but his political career was dealt a blow in August 1931, when police responding to his call to stop Communist-led antieviction actions at one of his properties killed three black protestors.35

Along with Edward H. Wright, whom Mayor Thompson appointed to be the city’s assistant corporation counsel as a reward for getting out the black vote in the 1915 election, DePriest sat atop a black submachine that funneled votes and funds from the South Side’s 2nd and 3rd Wards into the Republican Party machine in return for political appointments for blacks, city jobs for Bronzeville residents, and a range of administrative and legislative favors for black businesses. As Second Ward alderman, DePriest served as intermediary between the Stroll’s gambling clubs and the Republican machine, a role that led to his indictment on corruption charges in 1917. After eventually being acquitted the following year by arguing that the protection bribes he had taken were merely campaign contributions, DePriest lost the aldermanic election of 1919 to Louis B. Anderson, who had filled his seat on the city council after his indictment. By 1920, with DePriest returning to his real estate business, three politicians pulled the strings of the black submachine—Second Ward alderman Anderson, Third Ward alderman Robert Jackson, and Edward H. Wright, who had been named Second Ward committeeman, a position that gave him the power to nominate judges and a range of other political officials. Another black official of considerable influence was African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church bishop Archibald Carey, whom Mayor Thompson named to the Civil Service Commission in 1927, giving him power over the city’s pool of municipal jobs. Under Wright’s leadership, the black submachine sought to use the electoral and financial resources of the Black Metropolis not only to increase patronage but also to increase the power of black politicians in the legislative process—a challenge that Wright took to heart. His refusal to accede to Mayor Thompson’s pressure on the nomination of a First Ward committeeman in 1926 led to his withdrawal from politics, a void at the apex of the black submachine that was filled in 1928, when DePriest was elected to the House to represent the First Congressional District of Illinois (which included the Loop and the black South Side).36

Despite the best efforts of Wright and other well-meaning black political officials, the black submachine reproduced the bread-and-butter political style that characterized Chicago politics citywide during the interwar years. This does not mean that black politicians did not spearhead some considerable advances for black Chicagoans. As floor leader in the city council, for example, Anderson led an initiative to raise the wages of all city employees, a measure that helped thousands of black civil servants. Due to the efforts of black aldermen, by 1932 African Americans constituted 6.4 percent of the municipal workforce, which nearly matched their 7 percent proportion of the population.37 Nevertheless, the leaders of the black submachine seldom weighed in publicly on the more systemic dimensions of racial injustice in the city, leaving the racial order intact. Although Thompson was hailed as a friend to blacks, he failed to act on the most pressing issues facing African Americans. For example, he refused to take any action, rhetorical or otherwise, against the campaign of bombings—fifty-eight incidents were recorded between July 1917 through April 1921—conducted by white homeowners’ associations against black residents and the realtors who sought to provide them housing in white neighborhoods. Such terrorism, combined with the rampant use of restrictive covenants, greatly accelerated the advance of segregation, increasing Chicago’s white-black dissimilarity index from 66.8 to 85.2 percent between 1920 and 1930.38 And, in a moment when the education issue was at the heart of progressive politics, Thompson never gave much thought to appointing an African American to the highly politicized board of education.

In the final analysis, however, it is difficult to take Chicago’s black political and economic establishment too rigorously to task for not advancing black aspirations in the political arena, in view of the enormous constraints they faced from the white political establishment, Republican and Democrat alike. Much more dubious was their influence in actively shaping a political culture and organizing a public sphere that proved highly resistant to grassroots political projects challenging the circumstances of social inequality within the Black Metropolis. The race men whose voices rang out loudest on the reigning issues of the day invested doggedly in the ideals of thrift, hard work, and entrepreneurial spirit, the lack of which, in their eyes, explained many of the problems working-class blacks faced in their daily lives. Oscar DePriest was perhaps behaving as a loyal member of the Republican Party—the party of Lincoln, one must not forget—when he declared on the floor of the House in 1930, “[I am not] asking for public funds to make mendicants of the American people, and I represent more poor people than any other man in America represents.” But such sensibilities also reflected the ethos of black capitalism embraced by middle-class residents of his Chicago district, where a lack of public assistance was causing the forcible eviction of unemployed tenants in his properties. Addressing a crowd of protestors in Washington Park in the tense atmosphere following the deadly antieviction riot of August 3, 1931, Robert Abbott echoed these same ideas when he argued that their troubles had come about because they had not “saved for the lean years.”39

Abbott’s views were not only pronounced on soapboxes. Along with churches, the black press played a critical role in shaping the perceptions of ordinary residents about the political, economic, and social circumstances prevailing in the Black Metropolis, and Abbott’s paper was certainly the most powerful of them all. While some scholars have described the Defender’s stance as “fluctuating” on certain issues (for example, in regard to labor unions), its coverage of grassroots movements for social and economic justice was normally colored by Abbott’s pro-business, pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps vision of the world. If the Defender supported unionization in cases when it seemed like the best means for advancing the race in the face of discriminatory actions by management, Abbott’s weekly, notes historian James Grossman, “opposed anything that smelled of economic radicalism.”40 Hence, while Abbott praised the Communist Party for expelling one of its white members for segregating guests at a social function in 1933, his position on Communist efforts to defend evicted black residents two years earlier had been unequivocal: in a Defender editorial several days after the antieviction riots, he had opined, “Communism is not in the blood of the Negro.”41

“POOR MAN’S BLUES”

Hence, while Abbott could embrace the racial egalitarianism of Communists, their efforts to uplift the poor were another matter altogether, which explains a great deal about his reluctance to throw the support of the “world’s greatest weekly” behind black Chicago’s most ambitious challenge to the political and economic arrangements of the Black Metropolis and the economizing logic of black capitalism: the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP). Following its successful unionization drive in New York in 1925, the BSCP, under the leadership of A. Philip Randolph, turned to the difficult task of organizing the many maids and porters living in Chicago. The BSCP was not a typical union in that porters were among Bronzeville’s labor aristocracy. But their middle-class wages depended on gratuities, which placed them in a degrading and precarious position in relation to white customers, who could decide to withhold tips to those not displaying the requisite subservient demeanor. Moreover, the BSCP was an all-black union, and the Chicago Urban League, under the direction of T. Arnold Hill, had taken a position against separate unions since the 1919 race riot. An influential member of the Urban League was Associated Negro Press founder Claude Barnett, whose newswire was unwavering in its criticism of the BSCP. But the most significant impediment to the BSCP’s success was the enormous power Pullman wielded on the South Side, where the company provided thousands of jobs and where it had bought considerable influence, in one way or another, with a good many of the race men of the Black Metropolis. Major black community institutions like the Provident Hospital and the Wabash YMCA, which provided a range of social services for Bronzeville’s working-class residents, depended on Pullman’s contributions for survival; the Pullman Porters’ Benefit Association of America, the company union, had considerable funds deposited in Binga’s bank; and Pullman money padded the revenues of both the Chicago Defender and the Chicago Whip. For these reasons, Chicago’s leading race heroes—Binga, Abbott, Overton, DePriest, and Wright—withheld their support from the BSCP as it struggled for survival in the early years of its unionization drive.

Even the active backing of famed journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, whose antilynching campaign in the 1890s had won her national recognition as a “race woman” and who had emerged as a force to be reckoned with in South Side politics after her Alpha Suffrage Club had effectively mobilized thousands of women behind the triumphant aldermanic candidacy of Oscar DePriest in 1915, proved to be of little help in winning over the top brass of the Black Metropolis to the BSCP cause. When Wells-Barnett asked the exclusive Appomattox Club, black Chicago’s version of the Commercial Club founded by Edward Wright in 1900, to give Randolph a hearing, she was told that the club could “not afford to have Mr. Randolph speak” because so many of the “men who are opposing him are members here and it would embarrass them with the Pullman Company.”42 A portrait of Pullman, it should be noted, hung in the club’s stately three-story building at 3632 Grand Boulevard.

Opposition to Randolph was also strong among many of black Chicago’s most influential religious leaders. Reverend Lacy Kirk Williams, who had allowed packinghouse and steel workers to use his Olivet Baptist Church for organizing efforts in 1919, voiced strong opposition to the BSCP, and Bishop Archibald Carey forbid Randolph access to any AME churches. Carey had a number of personal reasons to be loyal to Pullman. George Pullman had once helped stave off the foreclosure of his Quinn Chapel, and Carey’s amicable relations with the company made him the man to see in the Black Metropolis about procuring one of the enviable positions in the Pullman workforce. Nonetheless, Carey articulated his aversion to challenges to the white business establishment in broader terms: “The interest of my people,” he once proclaimed, “lies with the wealth of the nation and with the class of white people who control it.”43

This was the very notion that Randolph had been publicly squaring off against since 1917, the year he cofounded the magazine The Messenger with fellow Socialist Party member Chandler Owen to serve as the mouthpiece of the black labor movement. It was within the pages of The Messenger that Randolph confronted the ethos of black capitalism, presenting his own vision of the New Negro spirit that replaced the values of thrift and self-reliance emanating from the black business heroes of the day with those of economic rights, brotherhood, and “collective organized action.” “The social aims of the New Negro are decidedly different from the Old Negro,” he wrote in his 1920 editorial “The New Negro—What is He?” “He insists that a society which is based upon justice can only be a society composed of social equals.” Dismissing out of hand the emancipatory promises of black capitalism being celebrated by the Defender around the time of the opening of Binga’s state bank, Randolph further argued that “there [were] no big capitalists” in black communities, only “a few petit bourgeoisie” whose position was untenable anyway because “the process of money concentration [was] destined to weed them out and drop them down into the ranks of the working class.” As for the new political order of the Black Metropolis emerging at the time, Randolph proclaimed in the same editorial that “the New Negro, unlike the Old Negro, cannot be lulled into a false sense of security with political spoils and patronage.”44 This was a message he carried into the Chicago organizing campaign seven years later, when he unabashedly took on the pantheon of race men in the Black Metropolis—especially Robert Abbott, whose newspaper’s support, tacit or otherwise, was critical to BSCP success. In October 1927, Randolph told a large Bronzeville crowd assembled at the People’s Church and Metropolitan Community Center that Abbott had surrendered to “gold and power.”45

Randolph extended such reproaches to Chicago’s clergy as well—especially to the eminent Archibald Carey, who not only banned the BSCP from AME churches but also demanded that all AME ministers warn their congregants against the evils of labor unions. However, Randolph’s opposition to the black religious establishment lay not only in its ties to big business and the political machine; it grew out of a broader critique of how black churches had fallen victim to the economizing logic of the Black Metropolis. As early as October 1919, he had argued in an editorial entitled “The Failure of the Negro Church” that the black church had been “converted into a business . . . run primarily for profits” with an “interest . . . focused upon debits and credits, deficits and surpluses.”46 In the face of such tendencies, Randolph set out to devise an alternative theology that would align religion with a powerful language of social justice. Invited to the Yale Divinity School in 1931, he delivered a lecture entitled “Whither the Negro Church?” in which he urged black churches to develop “a working class viewpoint and program.”47

While most religious leaders were unreceptive to such messages, Randolph’s vision of working-class solidarity caught the attention of a handful of influential ministers. One of these was William Decatur Cook, the former pastor of Chicago’s Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, who had become a rebel pastor after having been ousted from his pulpit by Archibald Carey upon his nomination as AME bishop for the Chicago area. In fact, Cook’s removal indicated that he was already at odds with the more conservative church leadership. After holding services for a number of years in Unity Hall, the headquarters of DePriest’s People’s Movement Club, in 1927, the undaunted Cook took his some five hundred followers with him to the handsome sandstone Romanesque Revival church at 41st and Grand Boulevard, which had previously housed the First Presbyterian Church. Aligned with the Community Church movement, the Metropolitan Community Church defined its mission with the credo “non-sectarian, broadly humanitarian, serving all the people.” Cook’s church was thus a loyal friend to the BSCP.

In addition to Cook, Randolph had the unqualified support of Pilgrim Baptist Church pastor Junius Austin, a fervent Garveyite, who, having arrived in Chicago in 1926 from Pittsburgh, was relatively free of patronage entanglements and, presiding by 1930 over a congregation of some nine thousand faithful members, possessed the kind of power base that would allow him to remain free. Austin represented quite another version of black capitalism, one that shunned the competitive, profit-driven spirit articulated by Binga and his cohort. Back in Pittsburgh, he had developed a real estate cooperative that had enabled the purchase of some one thousand properties for black families. Once in Chicago, he quickly formed the Cooperative Business League, a venture that, according to the Pittsburgh Courier, “paved the way for the militant program that [gave] Chicago the largest number of Negro owned and operated enterprises of any city in the world.”48 And yet neither Austin nor his Cooperative Business League appeared in the pages of the Defender in 1926 and 1927, as Randolph and the BSCP were seeking to spread their vision of racial solidarity founded in a collective commitment to social equality.

By November 1927, however, the Defender had published a mea culpa regarding its stance on the BSCP:

It is felt and asserted by some that the Defender is opposed to the porters’ efforts at organization. . . . Whatever may be the merits of these charges, be it known by all whom it may concern that the Defender is a red-blooded four-square Race paper, which is unequivocally committed to the policy of supporting all bona fide Race movements. Therefore, we wish definitely to register that fact that we back and favor the right of Pullman porters and maids to organize into a bona fide union of their own choosing, untrammeled by the Pullman Company.49

Abbott’s reversal represented a critical turning point in the BSCP’s campaign. In 1935, the union would defeat the company union and win its charter from the AFL, paving the way for the Pullman Company’s decision to grant it official recognition in 1937. Four years later, in 1941, when Randolph spearheaded the March on Washington movement to protest racial discrimination in the war industries, which were flourishing as a result of the United States entering the hostilities overseas, the BSCP rose to national prominence as a major player in the struggle for civil rights.

The BSCP’s triumph had not come easily. By 1933, its total membership had dwindled to under seven hundred—a small fraction of the overall workforce—and were it not for the Roosevelt administration backing the Wagner Act of 1935, which outlawed company unions, it is doubtful the BSCP would have weathered the Pullman Company’s offensive. Red-baiting tactics also played a role in the BSCP’s struggles, especially after Randolph’s election as president of the Communist-driven National Negro Congress (NNC). This alliance between the BSCP and the NNC caused rifts between the Communist-influenced CIO and the more conservative leadership of the AFL while subjecting Randolph to pressure from the Dies Committee. In 1940, Randolph resigned as NNC president, claiming: “Negroes cannot afford to add the handicap of being ‘black’ to the handicap of being ‘red.’” And yet, what perhaps hampered the union most in Chicago was the continuing resistance from the city’s black establishment.

Somewhat ironically, what support the BSCP was able to muster in order to overcome this resistance enough to win recognition came from a group of militant middle-class women who were no strangers to the black establishment crowd. Ida B. Wells-Barnett rallied the women of her Wells Club to canvas their neighborhoods in support of the BCSP. In fact, as a member of Cook’s congregation at the Metropolitan Community Church, Wells-Barnett sat in the same pews as Robert Abbott and under the same roof as DePriest’s political headquarters—a building, as the story goes, that was provided to DePriest by telephone magnate and Commercial Club player Samuel Insull. Joining Wells-Barnett in her fight was another insider, Irene Goins, president of the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs (IFCWC) and founder of the Douglass League of Women Voters. Goins had the kind of pull that enabled her to bring Second Ward Republican committeeman Edward Wright and national Republican committeewoman Ruth Hanna McCormick to address the IFCWC. Like the old settler business crowd they were opposing, the influence these African American clubwomen wielded stretched across the color line, where it was entangled with the very patronage structure that Randolph had in his crosshairs. The involvement of such figures as Wells-Barnett and Goins on behalf of the BSCP was also critical to attracting prominent labor organizer and settlement worker Mary McDowell to the cause—the only white Chicagoan who took an active stand against the Pullman Company. McDowell made her support clear when on October 3, 1927, she addressed an audience of two thousand packed into Austin’s Pilgrim Baptist Church for a BSCP meeting organized by Wells-Barnett, Goins, and BSCP organizer Milton Webster. This show of force for the BSCP, with its interracial cast of notables, was enough to push the hand of Abbott, who at the time was noting a drop in circulation due to talk of a boycott protesting his paper’s stance. The BSCP had clearly hit Abbott where it hurt most by revealing, as Beth Tompkins Bates has argued, “the contradiction inherent in advocating black freedom through paternalistic relations.”50

Certainly, something of a popular groundswell had been set in motion as clubwomen activists brought the BSCP’s message of economic rights and racial dignity into the homes of working-class neighbors who, understandably, would have been receptive to such appeals. Historian Jeffrey Helgeson has recently argued that these circumstances represented a broader trend of community-based activism around quality-of-life issues led by women who were acting pragmatically to sustain the conditions of their households and neighborhoods in the interwar Black Metropolis.51 Although Wells-Barnett and Goins were somewhat extraordinary race women, many of the more ordinary middle-class clubwomen who answered their call had entered the milieu of political activism as a means of addressing the ills of the city that were arriving at their doorsteps: crime, prostitution, and creeping slum conditions created by the spread of the nefarious kitchenettes. Whereas some scholars have viewed such bread-and-butter struggles to sustain the “home sphere” in a conservative light—as the individualistic reflexes of strivers and climbers seeking respectability and stature—the mobilization of clubwomen for the BSCP suggests that women engaging in the politics of home and neighborhood could also embrace more ambitious forms of collective activism.52 Yet it would be misleading to overstate the power of such forms of activism to dilute the potent ideological brew produced by the intermingling notions of entrepreneurial initiative, personal responsibility, and racial uplift that were so central to the spirit of black capitalism in the interwar Black Metropolis. In the final analysis, the moral of the BSCP story is not its triumph but rather the dogged resistance it faced in achieving it. Regardless of the Urban League’s position on race-based unions, the BSCP’s approach was in line with the spirit of racial unity of the times, yet its collectivist appeal and its unabashed challenge to the ethos of black capitalism was hard to digest for the black power elite and enough members of the black middle class—professionals, small businessmen, and civil servants—who saw their interests as aligned with the Appomattox Club crowd.

Moreover, the politics of the home sphere that brought middle-class folks and their well-heeled neighbors together in church-based and neighborhood-based clubs seeking to lift up their impoverished neighbors and the race played out in the context of frantic real estate speculation—yet another force working to economize the fabric of neighborhood life in the Black Metropolis. By the late 1910s, seventeen South Side realtors were running listings in Black’s Blue Book, with several of the more ambitious, such as DePriest and DePriest, taking out eye-catching ads. Sensing the trend in the making, one realtor, Dr. R.A. Williams, implored potential home buyers to “Make Your Dream Come True,” warning them that “every rent day sees a little more money gone and you a little further behind.”53 By the mid-1920s, the black press was hailing what the Defender referred to as the black “obsession” with homeownership and the “friendly spirit of rivalry” motivating black homeowners to join “neighborhood improvement associations.” In an editorial entitled “Neighborhood Pride,” the paper’s editors opined that the increasing number of blacks seizing “the opportunity to invest [their] earnings in property” was “the best thing that ever happened to [the race].”54 At the start of the following year, Anthony Overton’s Half-Century Magazine proudly announced that “$10,000,000.00 of Chicago real estate had gone over to Colored people in the past year.”55

Indeed, like many other commercial activities in the Black Metropolis, the real estate industry held out great promises for advancing the race. Exemplifying this alignment of collective racial progress with individual property acquisition was a 1923 ad placed by the Sphinx Real Estate Improvement Corporation in the Defender reminding potential black homeowners that of the “fifty million dollars per year . . . paid out by the Colored renters of Chicago . . . less than 5 percent . . . is retained by the Colored race or controlled by them for the improvement of their own living conditions.”56 Such sentiments, according to the work of historian N.D.B. Connolly, reflected the critical importance of property and real estate to black politics in the first half of the twentieth century. Connolly argues, “Owning rental real estate and owning one’s own home promised black people a measure of individual freedom from the coercive power of wage labor, landlords, and the state.”57 But Connolly also describes another side to this story—the contradictions that arose as black leaders seeking to uplift the race pursued economic activities that extracted resources from those they were seeking to uplift. And such contradictions also extended into the political sphere, as black landlords cooperated with white elites invested in maintaining a racially unjust status quo. While these circumstances certainly characterized the real estate dealings of Overton, Binga, and DePriest, perhaps even more significant for the Black Metropolis was the way in which its transformation into a real estate frontier in the 1920s reshaped its political culture. With residents increasingly bombarded with advertisements warning them not to miss the golden opportunity, an economizing ethos of “getting ahead” began to eclipse that of “advancing the race.” “Have you invested in Chicago real estate?” asked another Sphinx Real Estate ad. “Those who have bought Chicago property in the last ten years have made money and values are increasing every year.”58 And yet another ad in the Defender from a Gary, Indiana, real estate agency implored potential buyers to get into the market there: “Putting things off has kept many men poor—perhaps this is your case. Action has made all rich men.”59

The transformation of the family home into a financial investment—a critical development in the neoliberalization of the political cultures of metropolitan spaces, black and white alike, over the course of the twentieth century—was a phenomenon that was hardly specific to the Black Metropolis, Harlem, or any other of the country’s larger black ghettos. Nor was the tendency of developers to take advantage of the situation. And African Americans were hardly alone in their tendency to imbue their property with a sense of racial and civic duty. Working- and middle-class whites buying into the hopes and promises of homeownership on the other side of the color line were also increasingly viewing their properties in such terms, as fears of black invasion increased and grassroots struggles to hold the line against blockbusting real estate agents proliferated. And yet the blockbusters cynically betraying white homeowners for quick and substantial monetary gain were clearly regarded as villains, whereas the black developers who were ripping up buildings and charging exorbitant rents for substandard apartments were cast as race men and community leaders. This explains a great deal about how the clubwomen activists of the Black Metropolis could mobilize to help their poorer neighbors while embracing a pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps view. If, as Helgeson has argued, these women did help to create “resilient local bases of power and a long and rich tradition of black liberal politics” that led blacks to make demands on the black submachine as well as New Deal relief agencies in the years to come, they also participated in shaping a political culture that proved hostile to many of the most assertive struggles for social justice in the early 1930s: the Communist-led actions against housing evictions, unemployment, and the lack of adequate welfare relief.60 The political sympathies of a good many clubwomen activists lay not with such campaigns but with the more respectable Chicago NAACP, which, during the very moment antieviction protestors and Unemployment Councils were hitting the streets, was fighting for its survival. Indeed, if the local NAACP took on a more active role beginning in 1933 under the leadership of former Chicago Whip editor and Yale graduate A.C. MacNeal, one of the key forces behind the Don’t Spend Your Money Where You Can’t Work campaign, it had no real economic program in the midst of an economic catastrophe, and its reliance on the Appomattox Club crowd meant it would do little to become relevant to working-class blacks.

Hence, as on the other side of the color line, the political culture of the Black Metropolis could muster little opposition to the reigning political and economic order, even as that order lay in shambles. After 1929, most of what had been invested in black banks and businesses—in hope and money—had vanished, and even the likes of Edward Wright had kitchenettes on his block. Courageous were those agitating for jobs, housing, and relief in the 1930s, but their ranks were almost impossibly thin. By the mid-1930s, committed Communists in the city numbered about four hundred (although there were enough fellow travelers to swell the crowd to over a thousand when they demonstrated for relief). After dropping to 658 in 1933 from a 1928 peak of 1,150, membership in the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters rebounded to over 1,000 by 1935, but there was no getting around the fact that seven years had passed with no gain.

It was within this context that the Black Metropolis played host in February 1936 to the first convention of the National Negro Congress (NNC), which brought over seven hundred delegates, including such notables as Harlem’s famed Baptist pastor Adam Clayton Powell Jr.; James W. Ford, black vice presidential candidate for the Communist Party in 1932 and 1936; the National Urban League’s Lester Granger; and the NAACP’s Roy Wilkins, as well as a number of leading writers, artists, and intellectuals, including Richard Wright, Langston Hughes, and Arna Bontemps. The event was held at the Eighth Regiment Armory, whose interior hall was draped with banners, one of which read “Jobs and Adequate Relief for a Million Negro Destitute Families.” Randolph could not attend the event but he sent another BSCP official to deliver a spirited speech proclaiming that “the problems of the Negro people [are] the problems of the workers, for practically 99 per cent of Negro people win their bread by selling their labor power.”61 “The NNC convention in Chicago proved unique,” historian Erik Gellman has argued, “because its participants not only talked about working-class blacks but also looked to them for leadership.”62 Nevertheless, while receiving praise in the Defender, the convention also stirred up a great deal of controversy. Several religious leaders stormed out, and reporters covering the event noted undercurrents of discontent among the delegates concerning the radical tone of the proceedings, the large presence of whites and Communists, and the notable absence of old guard black leaders like W.E.B. Du Bois, James Weldon Johnson, and Charles S. Johnson.63 In the end the NNC convention hardly left a footprint within the political culture of the Black Metropolis. Two years later, the scathing critiques of capitalism that had filled the Eighth Regiment Armory seemed like distant memories as Junius Austin urged the crowd gathered for the Negro Business Exposition in the very same building to take on racial oppression by buying black and supporting the retail business of the South Side’s biggest policy kingpins.

Not even the stages of the nighttime Stroll, where jazz and blues performers sang about the trials of working-class city life to enthralled crowds of migrants, seemed to offer much spiritual opposition to the gospel of black capitalism. The blues, in particular, has long been associated with a “black cultural front” that brought together writers, artists, musicians, and labor activists in the interwar years, a perspective based, in part, on the number of blues standards circulating around the scene that articulated the injuries of class in northern ghettos—for example, Mamie Smith’s “Lost Opportunity Blues” and Bessie Smith’s “Poor Man’s Blues.” Hence, the blues and jazz opened up discursive spaces for migrants negotiating the difficulties of urban life in the North, and with the explosion of the race records industry in the 1920s, these spaces extended beyond the venues of the Stroll. Okeh Records, which had become a major race records label by the early 1920s, quickly set up recording operations in Chicago, seeking to tap the energy of the local scene there by recording some the Stroll’s most prominent performers: King Oliver, Louis Armstrong, Ethel Waters, Alberta Hunter, and Duke Ellington, among others. Chicago blues and jazz performers transformed the bars, clubs, and theaters of the Stroll into their own churches, offering spiritual catharsis and fellowship to working-class blacks dealing with the cultural tensions and economic hardships of their new life in Chicago. Gospel great Thomas Dorsey, who worked the club scene before becoming the “father of black gospel music” as music director at Pilgrim Baptist Church, evoked such spiritual powers in describing a performance of blues queen Ma Rainey:

When she started singing the gold in her teeth would sparkle. She was in the spotlight. She possessed her listeners; they swayed, they rocked, they moaned and groaned, as they felt the blues with her. A woman swooned who had lost her man. Men groaned who had given their week’s pay to some woman who promised to be nice, but slipped away and couldn’t be found at the appointed time. . . . As the song ends, she feels an understanding with her audience. . . . By this time everybody is excited and enthusiastic. The applause thunders for one more number. Some woman screams out with a shrill cry of agony as the blues recalls sorrow because some man trifled with her and wounded her to the bone.64