FOUR

The Boss and the Black Belt

If, as historian Arnold Hirsch has claimed, the 1940s was an “era of hidden violence” along Chicago’s color line, the race issue was clearly out of the closet by the early 1950s.1 In fact, postwar Chicago-style racism made its dramatic worldwide debut in July 1951, when thousands of angry whites took to the streets in the suburb of Cicero to protest the settlement of a single black family there, overwhelming the town’s police force and causing Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson to send in National Guard troops. Lying at the city’s eastern limits, about seven miles away from the Loop, this tough, working-class town, which had once served as the Capone syndicate’s base of operations, was not exactly Chicago. But it was close enough, and news of Chicago racism hit international newswires. More locally, the Cicero riot was something of a cause célèbre that witnessed several hundred and perhaps thousands of young men from Chicago pouring into the neighboring town in cars and on city buses to lend a hand to what one racist organization referred to as “the brave youth of Cicero.”2 Arnold Hirsch was the first historian to examine the arrest lists from the several nights of rioting in order to explain the motives of those who took to the streets in a frenzy of racial hatred. The Cicero rioters, he concluded, were largely residents of the neighborhood trying to protect their community from a racial invasion that they believed would destroy the very fabric of their lives. Yet Hirsch’s analysis overlooks something very important that was transpiring in Cicero: the arrest records for the final few nights suggest that once news of the demonstration spread, it changed from a territorially based action to a much broader rally against integration that pulled in participants from West Side Chicago neighborhoods—some a considerable distance away from the scene at 6139 West 19th Street in Cicero.3 The Cicero riot revealed that the more “hidden violence” of the previous decade—the hit-and-run vandalism and nighttime raids, which, due to pressure from the mayor’s office, had been kept off the front pages of the city’s dailies—was by the end of the 1940s spreading throughout the city. Even though the events of Cicero were eye-opening for those outside Chicago, working-class ethnics and their black neighbors residing anywhere near the color line understood very well that this kind of thing was business as usual. Nonetheless, while African Americans in Chicago certainly did not lack events to reveal to them the racism they faced in their daily lives, the widespread media coverage given to the Cicero riot could only have emboldened the city’s black leadership.

FIGURE 7. Young rioters brazenly confronting police in Cicero in July 1951. Photo from Ullstein Bild via Getty Images.

Moreover, there were other sources of black discontentment simmering in Chicago around this time. Mayor Kennelly’s zeal for reform had begun to arouse cries of racial injustice in William Dawson’s five black-majority wards. Although Dawson’s political submachine had been critical to Kennelly’s election in 1947, just as it had for Kelly in the two previous mayoral elections, the mayor began to break the unwritten rule that Dawson and his underling ward bosses should be given free rein over the illicit operations that had created a parallel underground economy in black Chicago. Two rackets in particular, policy wheels and jitney cabs, headlined Kennelly’s crusade. Under the system Kennelly had inherited from his predecessor, the police were supposed to give a wink and then close their eyes to such activities, both of which provided thousands of jobs to ordinary black residents and substantial revenues to the black politicians that protected them. But within months after the election, different police details began making raids on South Side policy operations.

By the late 1940s, black Chicagoans began to view such actions as constituting racial injustices, especially as police officers proved to be showing much greater dedication in upholding the laws against policy and gypsy cabs than they did in defending the rights of innocent black citizens being attacked by racist mobs. In July 1946, for example, the Mayor’s Commission on Human Relations reported several such cases of police negligence, including an officer who refused to arrest two vandals because he was off duty, a policeman asleep at his post, and another who “expressed opposition to guarding residences of Negroes.”4 Especially galling, in this sense, was the crackdown on the jitney cabs, a trade that had developed in the first place because white taxi companies generally refused to serve black neighborhoods. Moreover, the Capone gang had tried repeatedly in the 1920s and 1930s to take control of the South Side policy business, leaving Kennelly open to charges that he was backing a takeover of this lucrative source of black wealth by the white syndicates. To make matters worse, the mayor had continuously refused to give any credence to Dawson’s arguments about why a harmless vice like policy should be left alone. “Our people can’t afford to go to race tracks and private clubs,” Dawson reportedly told the mayor, “so they get a little pleasure out of policy.” In an episode that has become legendary in accounts of Dawson’s storied career, the boss of black Chicago refused to talk to Kennelly until just before his reelection bid in 1951, when in a heated backroom meeting, Dawson blasted the mayor: “Who do you think you are? I bring in the votes. I elect you. You are not needed, but the votes are needed. I deliver the votes to you, but you won’t talk to me?”5

However, if Dawson was voicing complaints that might have helped to fuel the growing sense of racial injustice in black Chicago, one would be mistaken to think of him as a civil rights activist. In his 1960 study Negro Politics, political scientist James Q. Wilson categorized black leaders of the pre–civil rights era as either those who promoted the “status” of the black community or those who fought for its “welfare.” According to this scheme, the status-oriented leaders were the ones supporting objectives that uplifted the race by defending black rights, such as integration and equal educational and employment opportunities, while the welfare-oriented leaders focused on bread-and-butter issues that met the social needs of the black poor.6 To say that Dawson, who was heard on a number of occasions comparing himself to Booker T. Washington, belonged to the latter camp does not adequately describe the situation. Not only did Dawson not fight for status issues, but his very position depended on the failure of those who did. Segregation had made Dawson, and he knew all too well that integration threatened to unmake him. Until 1948, when the Supreme Court’s decision in Shelley v. Kraemer struck down the use of contracts between homeowners to prohibit sales or rentals to blacks and other perceived racial undesirables in the eyes of white residents, African Americans were largely relegated to the three main community areas that made up the Black Belt. If those championing racial integration were to carry the day, many of the votes underpinning the black submachine would be dispersed throughout the city, thereby deteriorating Dawson’s base and the harvest of votes he could deliver to the Democratic machine. Dawson’s fear of civil rights activism was so pronounced, in fact, that, when serving on the Civil Rights Section of John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 1960, he had tried to persuade the other members of the committee to drop the term civil rights from its name, arguing that the words might “offend our good southern friends.”7

Yet Dawson could take some consolation in the fact that he did not face his dilemma alone. In fact, the whole Cook County Democratic Party machine depended on Dawson’s ability to deliver votes. Even though by the early 1950s Chicago blacks had not abandoned the party of Lincoln to nearly the same extent that African Americans in the rest of the nation had since the 1936 presidential election, when some 76 percent had cast their vote for Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dawson’s black submachine had nonetheless provided Democratic candidates with Black Belt majorities—albeit somewhat slim ones—that had ensured their victories in the elections of 1939, 1943, 1947, and 1951.8 However, for the Democratic machine, civil rights agitation for integration represented a double-edged sword. Not only did it threaten to undermine the pivotal electoral advantage the Black Belt had been providing, but even more importantly, it held the potential to wreak political havoc in the machine’s white working-class strongholds, causing many families to move to outlying Republican wards and to the suburbs and spreading feelings of animosity among those left behind. For the next few decades, two opposing forces—the black struggle for integration, equality, rights, and power on the one hand and a white reaction that historians have described as “defensive localism” and “reactionary populism” on the other—would shape a treacherous landscape for mayoral politics in the Windy City.9 With the increasingly rights-conscious Black Belt holding the margin of victory, one could not afford to be viewed as soft on questions of racial justice; take too aggressive a stand though, and the fury of the white backlash threatened to make even the strongest of black votes irrelevant.

As early as 1954, the year the U.S. Supreme Court declared segregated schools to be unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, these two counterforces of black struggle and white reaction were fighting it out in a small community of steelworkers in the southeast corner of Chicago. In the far-flung neighborhood of South Deering a set of two-story brick buildings constructed around grassy courtyards—the prototypes of the “garden apartment” public housing complexes built in the New Deal era—became, quite by chance, the city’s test-case for racial integration. The affair began around the summer of 1953 when a Chicago Housing Authority official mistakenly granted an apartment in the Trumbull Park Homes project to a light-skinned black woman named Betty Howard. When, just days after moving in, Mrs. Howard was sighted with her darker-skinned husband, residents in the area launched a campaign of terrorism that forced the Howards to board up their windows and wait for police escorts every time they wanted to step outside their home. What amounted to an ongoing race riot continued for over a year, during which time embattled CHA director Elizabeth Wood took on the mob by moving ten other black families into Trumbull.

In an effort to understand what lay behind the intensity of South Deering racism, the American Civil Liberties Union enlisted a “spy” to hang out at local bars and parks and record the conversations he overheard, a move that unwittingly yielded some compelling documentation of the shadowy, everyday milieu of 1950s white reactionary populism. In the conspiratorial nightmares and daydreams of South Deering residents, we learn from these conversations, powerful Jews pulled the strings of the city’s housing policies in order to promote intermarriage and exploit the real estate market, and it was the handful of Trumbull’s harried black families, not the established white residents, who had the upper hand. “I heard there is an organization of smart niggers that use certain other niggers like this fellow Howard to move into a neighborhood, and this ruins the neighborhood,” one patron at a local bar told the crowd one afternoon, “and then these smart ones with money come in and buy up the property at a low price and then sell to other niggers at a high price.”10 For many of the folks sharing such anxieties over beer and cigarettes, the Brown ruling was not so much about desegregating southern schools as it was about integrating their own neighborhoods. Here was an early glimpse of the now very familiar populist rhetorical style of turning the world upside down—to put “liberals” and minorities on top and average, white, middle-class taxpaying people on the bottom—that infused the conservative ascendancy in the postwar United States from Nixon’s “silent majority” backlash to George W. Bush’s triumphant alliance of neoconservatives and evangelical Christians. The heated barroom conversations of South Deering suggest that this sense of victimization at the hands of liberals was not merely spoon-fed by Republican politicians to their antiliberal constituents; rather, it was elemental to the everyday experience for many working-class whites in the metropolitan United States, and it was an emotion that crystallized most visibly in places where African Americans were mounting spirited challenges to their own victimization.

By the fall of 1954, the South Deering situation had been the subject of a nationally televised news broadcast and numerous articles in the Chicago Defender, and Elizabeth Wood had been forced out of her post. But Wood’s ouster had done little to recoup the damage Kennelly had sustained over the situation. His failure to adequately protect blacks in Trumbull Park had made him the scourge of black Chicago, and yet his association with the whole affair was hardly reassuring to working-class whites living around the color line. More importantly, both his reform crusade and his falling out with Dawson had made him a persona non grata with the leadership of the Cook County Democratic machine, whose new chairman, Richard J. Daley, began maneuvering behind the scenes to replace him as the machine’s candidate in the upcoming mayoral elections. In fact, not much maneuvering was required to get the job done. As chairman and thus “boss” of the machine, Daley controlled the selection of the “slating committee” responsible for recommending to the Cook County Democratic Central Committee all the candidates to run on the machine’s ticket. Suffice to say that few were surprised when the Central Committee approved the slating committee’s recommendation of Daley for mayor by a vote of 47–1, with Kennelly’s campaign manager casting the lone dissenting vote.

Few people, if anyone, in the room that day could have sensed the historic significance of their choice. Few could have imagined that Daley would become the quintessential boss, that he would create the nation’s most powerful political machine at a time when reformers were putting machines across the country to rest, that presidents would be indebted to him, and that it would take a heart attack to remove him from office twenty-one years later. Daley, to be sure, was ambitious, but by most accounts, he was hardly a visionary leader, and fortune more than anything else had placed him in a position to become the machine’s mayoral candidate in 1955. Three years earlier a powerful South Side bloc within the party had appeared to have effectively opposed Daley’s bid for party chairman, but in the midst of the selection process, Daley’s leading opponent, Fourteenth Ward alderman Clarence Wagner, had perished in a car accident while on a fishing trip in Minnesota, and Daley prevailed after all.

Yet Daley’s rapid ascent was not merely a matter of chance, even if chance had played a part. He was the right man for his time and place. Having grown up the son of a sheet-metal worker in a large Irish Catholic family in the working-class neighborhood of Bridgeport, where he continued to live after his election, Daley was intimately acquainted with the spirit of defensive localism that was developing across the city’s Bungalow Belt and white working-class neighborhoods. Moreover, Daley was a rhetorical genius, a virtual savant in the art of appealing to the common people with his heavy Chicago accent and straight-talking style, while avoiding any easily discernable position on the issues. This skill had the astonishing effect of enabling a Bridgeport kid who had run with the famously racist Hamburger gang to capture the endorsement of none other than the Chicago Defender, which, in a front-page editorial, opined that he had “taken a firm and laudable stand” on civil rights issues.11 In a hard-fought primary against Kennelly, who decided to try to go it alone after being dumped by the machine, Daley met his opponent’s charges of bossism with classic populist retorts about being a man of the people in a struggle against the “big interests.” But Daley best exhibited his talent for populist platitudes in his campaign against his Republican challenger, Robert Merriam.

A former Democrat from Chicago’s liberal Fifth Ward, which included the campus of the prestigious University of Chicago and the surrounding Hyde Park neighborhood, home to a constituency that machine politicians referred to contemptuously as “lakefront liberals,” the stately and well-spoken Merriam staked his campaign on the reform spirit sweeping across U.S. cities. But Merriam’s WASP background and his social distance from most Chicagoans played right into Daley’s hands. Faced again with allegations of bossism, Daley swore to voters that he would “follow the training [his] good Irish mother” had given him. “If I am elected,” he added, “I will embrace mercy, love, charity, and walk humbly with God.” Moreover, when pushed on the thorny issue of public housing, Daley pronounced himself a proponent, but when asked where it should be built, he replied, “Let’s not be arguing about where it’s located.” Similarly, in contrast to Merriam’s very specific policy positions, Daley spoke repeatedly and vaguely about the need to protect the “neighborhoods”—“the backbone of the city,” as he called them.12 When I walk down the streets of my neighborhood,” he assured his supporters, “I see the streets of every neighborhood.” And sounding the old populist refrain, he promised that under his administration, “The sun will rise over all the Chicago neighborhoods instead of just State Street.”13

In the end, however, Daley’s populist rhetorical talents were mere icing on the cake. It was the machine, in all its organizational splendor, that pushed him over the top in what was a relatively close election by Chicago standards. The machine, as always, supplied Daley with a large financial edge and a veritable army of campaign workers, who, under the leadership of precinct captains, local fixers whose position depended on their ability to produce votes, pursued their objective through a range of illicit activities: from fraud to blackmail, to physical intimidation and worse. This was, of course, an old Chicago tradition. But what was somewhat new—and, in a sense, modern—about the machine’s campaign tactics under Daley was the very deft exploitation of white racial fears. Commenting on this campaign years later, famed Chicago journalist Mike Royko claimed: “Even before the phrase ‘white backlash’ was coined, the machine knew how to use it.”14 And it knew how to use it in a manner that barely even jeopardized black votes—due to the long reach of the machine into neighborhoods, up doorsteps, and into the very living rooms and kitchens of potential voters. The machine’s precinct captains could lean on scores of residents in their neighborhoods who were indebted to them for a job or any of a long list of political favors and services. This extensive network of loyal supporters enabled Daley to play a double game with the race issue.

Thus, while Daley avoided making any public statements that painted him as unsympathetic to the plight of black Chicagoans, his operatives were spreading the word behind the scenes that he was no friend to racial integration. This message was transmitted, in part, through a shameless smear campaign to stir up racial concerns about his opponent. Machine cadres, for example, circulated letters in white neighborhoods from a bogus organization called the American Negro Civic Association urging residents to vote for Merriam because he would make sure blacks found proper housing throughout the city. They also spread rumors that Merriam’s first wife, who was born in France, was part black. Even though many people realized this was all pretty much a sham, they understood that the machine’s involvement in such shenanigans meant that its candidate was no civil rights crusader. Not only were Daley and his people precocious in their understanding of backlash politics, but they were also ahead of their time in their use of “coded” language to appeal to angry white voters on racial issues without really saying anything specific that could raise the ire of black voters.

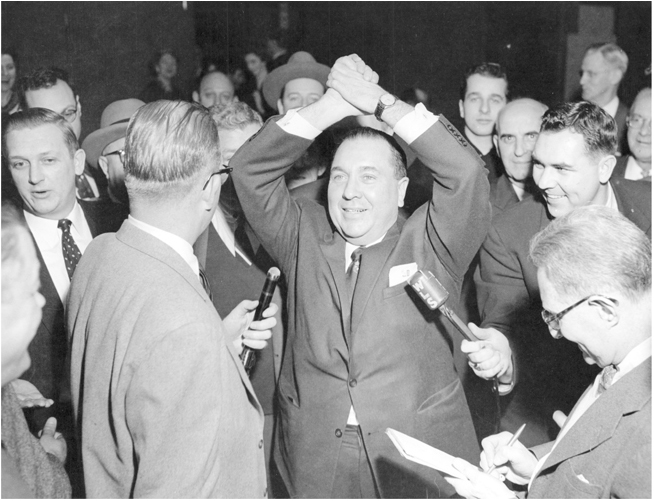

FIGURE 8. Richard J. Daley celebrates his first mayoral election victory in 1955. Richard J. Daley Collection, RJD_04_01_0012_0002_025, University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

Hence, despite the endorsement of Chicago’s largest newspapers, which gave Merriam’s charges of corruption and bossism front-page exposure, Merriam amassed only 589,555 votes to Daley’s 708,222. But the election was much closer than it looked. The candidates ran evenly in most of the city, with Daley’s margin of victory lying in his overwhelming dominance in the machine’s core wards—referred to by political commentators as the “automatic eleven.” In the five black wards that Dawson controlled, Daley had garnered a nearly 50,000-vote margin; with the votes for him in several other black wards, the total black contribution to Daley’s victory was a decisive 103,000 votes.15

Later that same year, African Americans in Montgomery, Alabama, most of whom had been disenfranchised by terror and administrative chicanery, would begin a powerful bus boycott that would help to launch a movement for civil rights aiming to renew American democracy. Southern blacks, with some help from the Supreme Court, were pushing themselves across a new threshold of modernity, pulling the nation along with them. And as Adam Green has argued, African Americans in Chicago were, in this very same moment, developing a new consciousness of their connection to a larger national black community that spanned both sides of the Mason-Dixon line—a bond soldered by the revelation of Chicago-native Emmett Till’s brutal murder in rural Mississippi, where he had allegedly dared to flirt with a white woman while visiting relatives in August 1955; the experience of beholding the images of fourteen-year-old Till’s mangled, bloated body, exposed sensationally in the pages of the Chicago-based black publication Jet, produced, according to Green, a “moment of simultaneity” between blacks all over the country that laid the foundations for the northern civil rights struggle in the 1960s.16 Viewed in the light of these circumstances, the key role played by Chicago blacks in the election of Richard J. Daley appears an act of epic historical irony—even more so because Daley himself stood not for a return to the old order or even a maintenance of the status quo. Rather, the new mayor was a zealous modernizer. He would move almost immediately to upgrade Chicago’s transportation infrastructure, make Chicago one of the first cities to fluoridate its water, and bring in a battalion of state-of-the-art street cleaners that enabled the city to remove ten thousand more tons of street dirt (the calculation of such a figure in itself suggests the logic of linear, scientific progress in operation). In Daley’s Chicago, Bauhaus planners sponsored by modernist architectural trendsetter Ludwig Mies van der Rohe would design high-rise housing projects in an effort to provide more efficient housing for ghetto-dwelling blacks. Of course it was impossible for Chicago blacks to have known that they were helping to elect a man who would preside over the invention of the modern black hyperghetto, but it would not take long before they understood their place in the new order.

WRECKING MACHINE

To the untrained eye, it might seem contradictory that Richard J. Daley—a Democrat who had come of age politically in a moment when the Democratic Party defined itself as the defender of society’s disadvantaged—would manage a city that so clearly relegated African Americans to second-class citizenship. “My dad came out of the Roosevelt era and the Depression,” Daley’s son Richard M. Daley would later claim. “One person and one party made a difference in his life—that’s what everybody forgot when they called my father and other people political bosses.”17 Although Richard J. Daley’s legacy would be marked by his truculence in the face of civil rights protests, his “shoot-to-kill” order after rioters took to the streets in anger over Martin Luther King’s assassination, his unabashed will to turn the full wrath of police repression against student demonstrators outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention, and his general unwillingness to alter the processes making Chicago the most segregated city in the United States, more recent accounts, many from people close to him and his son, have complicated Daley’s place in the pantheon of backlash cranks. Daley, some have pointed out, initially preferred the construction of much more humane, four-story housing projects to the alienating high-rise complexes that would come to dominate large swaths of the city, and he even travelled to Washington on two occasions to plead, ultimately unsuccessfully, for the additional funding that would make this possible.18 Some of Daley’s apologists, moreover, have claimed that he genuinely believed he was acting as a New Deal liberal should when he authorized the expenditure of government funds to move blacks out of deteriorating slums and into new apartment buildings. Put such facts together with his close ties to liberal Democratic icons like John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, and Daley seems not so implausible as a New Deal–style Democrat after all.

Yet to understand Daley in these ideological terms is to completely misunderstand the Chicago machine system that gave meaning to his every move. In one of the most definitive studies of the Daley machine to date, sociologist and political insider Milton Rakove described the machine’s raison d’être as “essentially nonideological.” “Its primary demands on its members are,” he claimed, “loyalty and political efficiency. In return, it carries out its obligations by providing its members with jobs, contacts, contracts, and its own ‘social security’ system.”19 While Daley would become renowned for his humorously botched phrases—one of the more colorful was “the police are not here to create disorder, they are here to preserve disorder”—much more emblematic of his political acumen was his oft-quoted maxim: “good government is good politics.”

This idea more than any vague notion of liberalism, democracy, civic duty, or even human compassion guided Daley’s decision to approve the construction of two adjoining strips of high-rises—Stateway Gardens and the Robert Taylor Homes—that would together constitute the world’s longest and largest housing project of its time. By the late 1950s, after the blueprints for these projects had been hashed out, one would have been hard-pressed to find anyone able to make a convincing argument that this seemingly endless, four-mile corridor of almost indistinguishable concrete slab structures, all occupied exclusively by blacks, would not create a ghetto far more sinister than the one it was replacing. But to build such structures was good government in Daley’s eyes, because of the immense political benefits that would accrue from doing so. Not only would this housing “solution” be useful for steering clear of the thorny issue of racial integration, but also, thanks to Title I of the Housing Act of 1949, the federal government would be heavily subsidizing the work. In effect, a flow of capital would move through the mayor’s office, where it would be magically transformed into patronage—the jobs and contracts that lubricated the machine and made it run. When Daley took office, the city of Chicago employed nearly 40,000 people. If, according to Rakove’s estimate, each patronage job handed out translated into some ten votes from family members and friends, this meant that the Daley machine would enter each election with a lead of roughly 400,000 votes. But federally subsidized public works projects of the magnitude of those that built Chicago’s numerous high-rise housing projects offered the possibility of expanding the machine’s patronage resources even more while drawing very little from the city budget. For every hard hat on the job, for every light bulb and bolt, for every inspector and supervisor, the machine was expanding its base exponentially.

FIGURE 9. Stateway Gardens at 35th and S. Federal, ca. 1958. Chicago Architectural Photographing Company. Chicago Photographic Collection, CPC_01_C_0282_006, University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

This patronage system had of course been fundamental to machine politics long before Daley had entered public life, but Daley’s great coup lay in understanding the need to take the system to another level and to reconfigure it so that he held all the cards. Patronage, it must be remembered, was under threat in 1955. Reformers had gained the upper hand in many major U.S. cities, and, as was demonstrated by the favorable press coverage of both Kennelly and Merriam’s anticorruption campaigns, even Chicago seemed ready for reform. More importantly, however, the city had entered a period of economic decline, which threatened to reduce the budget and with it the reservoir of patronage resources at the machine’s disposal. Generous federal government programs providing subsidized long-term loans to veterans and other potential middle-class homeowners had sparked a massive migration to the suburbs, and Chicago, like many other cities, was witnessing the flight of people and jobs into the rapidly growing outlying areas, where the American dream of a home of one’s own on a plot of green could be realized. What was happening to Chicago was part of a much larger story of deindustrialization and metropolitan sprawl that began sucking the life out of the urban core beginning in the late 1940s. The future was not broad shoulders and smokestacks but white collars and air-conditioned offices, a situation emblematized as early as 1955, when Chicago lost its claim as “hog butcher of the world” to the city of Omaha, Nebraska.20 Yet the real estate and service activities that would eventually make the city prosperous again were, by the mid-1950s, far from being able to compensate for the declining manufacturing sector. When Daley took office, housing construction had come to a virtual standstill; only one major structure, the Prudential Building, had recently been added to the downtown skyline; retail sales at the swanky Loop department stores were falling fast; and real estate values in the downtown area had still not recovered from the 13 percent hit they had taken between 1939 and 1947.21 Moreover, with the black ghetto converging on the Loop from the south, business leaders were bracing for the worst. The Chicago of Daley’s first term was not at all the bustling, vibrant city it would become by the end of his second. It was more akin to the Chicago of Nelson Algren’s gritty 1951 novel City on the Make, a landscape of sordid gin joints and dingy alleys peopled by stew bums, swindlers, crooked politicians, and gangsters. Being a part of this city was, Algren famously quipped, “like loving a woman with a broken nose.”22

Chicago’s new mayor took such insults personally. A poignant Daley anecdote, whether the stuff of legend or truth, captures the bare-knuckled intensity of his investment in the city’s livelihood: the mayor once stopped his car so he could get out and, with his bodyguard looking on beside him, dispose of a piece of litter he had seen a pedestrian drop on the sidewalk. Yet for Daley, the goal of renewing Chicago was inextricably bound up with his own objective of holding on to power, and his political education told him that his hold on power was contingent on preserving and controlling the supply of patronage he could spread around. His first order of business was to bring patronage under his complete control in two ways that broke sharply with machine tradition. Despite promises to the contrary during his campaign, Daley refused to relinquish his position as Democratic Party chairman after being elected mayor. This not only handed him control of the party’s campaign funds, which he could distribute to the different city wards through his ward committeemen, based on who was most loyal and deserving, but it also gave him decisive influence over the selection of the full slate of the party’s candidates, including those for governor and both houses of the state and federal legislatures. These powers made every Democratic politician in the state beholden to Daley and thus ready to bend to his wishes. They also allowed Daley to become a player on the state and national stages, which could pay patronage dividends in some strange ways. For example, when Daley needed an increase in the city’s sales tax to pay for his ambitious plan to hire thousands of new police officers, firefighters, and sanitation workers, he went downstate to negotiate with Republican governor William Stratton, the one man who could ensure the approval of the state legislature for such a measure. Rumor had it that Stratton’s help came at a price: Daley’s agreement to slate a lackluster candidate against him in the coming gubernatorial election. “Daley turned purple and pounded his fist when he later denied the rumor,” wrote Mike Royko, “but he did indeed run a patsy against Stratton in 1956.”23

Daley’s second power play was to emasculate the city council, effectively reducing it to a rubber-stamp advisory board. This he did by forcing a number of procedural changes, the most important of which was transferring responsibility for formulating the city’s annual budget from the city council into his own hands. This represented an enormous shift in the balance of power between the mayor and the city council, a change that was reinforced by Daley’s elimination of the practice of requiring city council approval for any city contract over $2,500. Complementing such official changes were a number of tactics the new mayor pursued to limit the city council’s informal powers. All of the aldermen sitting on the city council, for example, possessed the authority to bestow a range of favors on constituents, most of which came at a price. One of the most profitable of these favors was the issuance of permits to construct driveways; under Daley, requests for such permits would now need to pass through the mayor’s office. The members of the city council were, of course, not happy about such restrictions on their power, but resistance was futile.

Daley may not have gotten away with such actions were he not also moving swiftly to make everyone with any financial clout in the city happy. The candidate who had run a populist campaign against the “big interests” quickly became the toast of State Street with a flurry of decisions that exhibited the progrowth ideology that would come to define the Daley era. What perhaps few expected of the kid who knew the summer stench of the stockyards was an unparalleled ability to draw massive amounts of both public and private funding to modernize and improve the city’s infrastructure. Once again Daley was the man for his time and place. The Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954 had extended generous federal funds for local governments to buy land in blighted areas and then sell it off to private developers for public housing and nonresidential projects, such as universities and hospitals. While policy makers and lobbyists in Washington debated what forms of redevelopment should be prioritized and which populations should be targeted by “urban renewal”—with the business community cheering for the rehabilitation of downtown business districts and liberals arguing for better housing for the poor—the matter would largely be settled on the local level, where municipal governments put the federal money to work. In Daley’s Chicago, the progrowth ideology was never in doubt, and all of the “trickle-down” arguments from the coalition of developers, bankers, and commercial interests that rallied merrily around their new mayor seemed like pipe dreams by the late 1960s, when black Chicago was engulfed by the flames of rebellion.

In this moment of black disillusionment about the unfulfilled promises of the civil rights movement, novelist James Baldwin provocatively referred to “urban renewal” as “Negro removal,” a description that fits the case of Chicago particularly well. Indeed, when Daley pushed his plan for the Robert Taylor Homes through the city council in May 1956, it was not yet clear just how this and the numerous other ghetto high-rises being planned and constructed would fit into the overall scheme. In fact, these housing complexes were among a number of public works projects being pushed forward by the mayor during his first term in office. The city was going to get new skyscrapers in the Loop, new expressways that connected the suburbs to the downtown business district, new parking garages to accommodate the additional rush of commuters, the new $35 million McCormick Place convention center on Lake Michigan that would make the city “the convention capital” of the nation, a new and improved O’Hare Airport, new bridges and train crossings, new government buildings, new police stations, and a new University of Illinois campus. Daley was unleashing the growth machine and it promised to make everyone involved fat—bankers and lawyers, realtors and developers, contractors and suppliers, politicians and friends. And the State Street crowd was jubilant. The old retailers like Marshall Field’s applauded the expressways and parking garages that would bring suburban shoppers safely and quickly downtown, and the top brass of the many Fortune 500 companies with headquarters in the Loop—in 1957 Chicago was second only to New York in housing corporate headquarters—saw a solution to the ghetto blight creeping northward from the South Side. The only inconveniences in this scheme were the human beings who remained after their neighborhoods were cleared away. What was to be done with them? Moreover, one could talk about holding off the ghetto, but what did this mean in a city that had seen its black population increase from 277,731 (8 percent of the total) in 1940 to 812,637 (23 percent of the total) in 1960? Here, alas, is where federally subsidized public housing fit into the big picture, and in a picture as black and white as Chicago’s was, urban renewal did indeed mean just what Baldwin said it did: “Negro removal.”

This was how a federal urban renewal program whose most idealistic framers viewed as capable of lifting up the urban poor, became, in Daley’s Chicago, a powerful means for reinforcing inequalities of race and class. To be fair, Daley inherited rather than invented the city’s growth machine; in fact, Chicago was a pioneer in early urban renewal efforts, lobbying the state legislature to pass the Blighted Areas Redevelopment Act and the Restoration Act of 1947, which granted it broad powers of eminent domain for acquiring large slum areas and selling them to developers, as well as state subsidies to sweeten the deal for investors. The legislation was largely the brainchild of a civic planning group called the Metropolitan Housing and Planning Council (MHPC), and in particular of two of its leading members—Chicago Title and Trust president Holman Pettibone and Marshall Field’s executive Milton C. Mumford—both of whom favored a downtown approach to the city’s redevelopment plan in order to stave off blight and reverse the trend of falling real estate values in the Loop. While downstate Republican legislators—many of them rural-based and hostile to anything that smacked of New Deal aid to urban blacks—were adamant that state funds would not be used to subsidize public housing for displaced residents of redevelopment projects, Pettibone and Mumford worked out a compromise that would create the Chicago Land Clearance Commission (CLCC) to deal with the housing of displaced residents. The idea was to bypass the Chicago Housing Authority and its nondiscriminatory tenant-selection policy. Pettibone hailed the legislation as “a pioneering combination of public authority and public funds with private initiative and private capital,” but the public side of the partnership had clearly been given a subsidiary role.24 By legislative sleight of hand, the capacity of public authorities to acquire and clear land and then sell it to private interests at below-market costs had come to be defined as a “public purpose.”

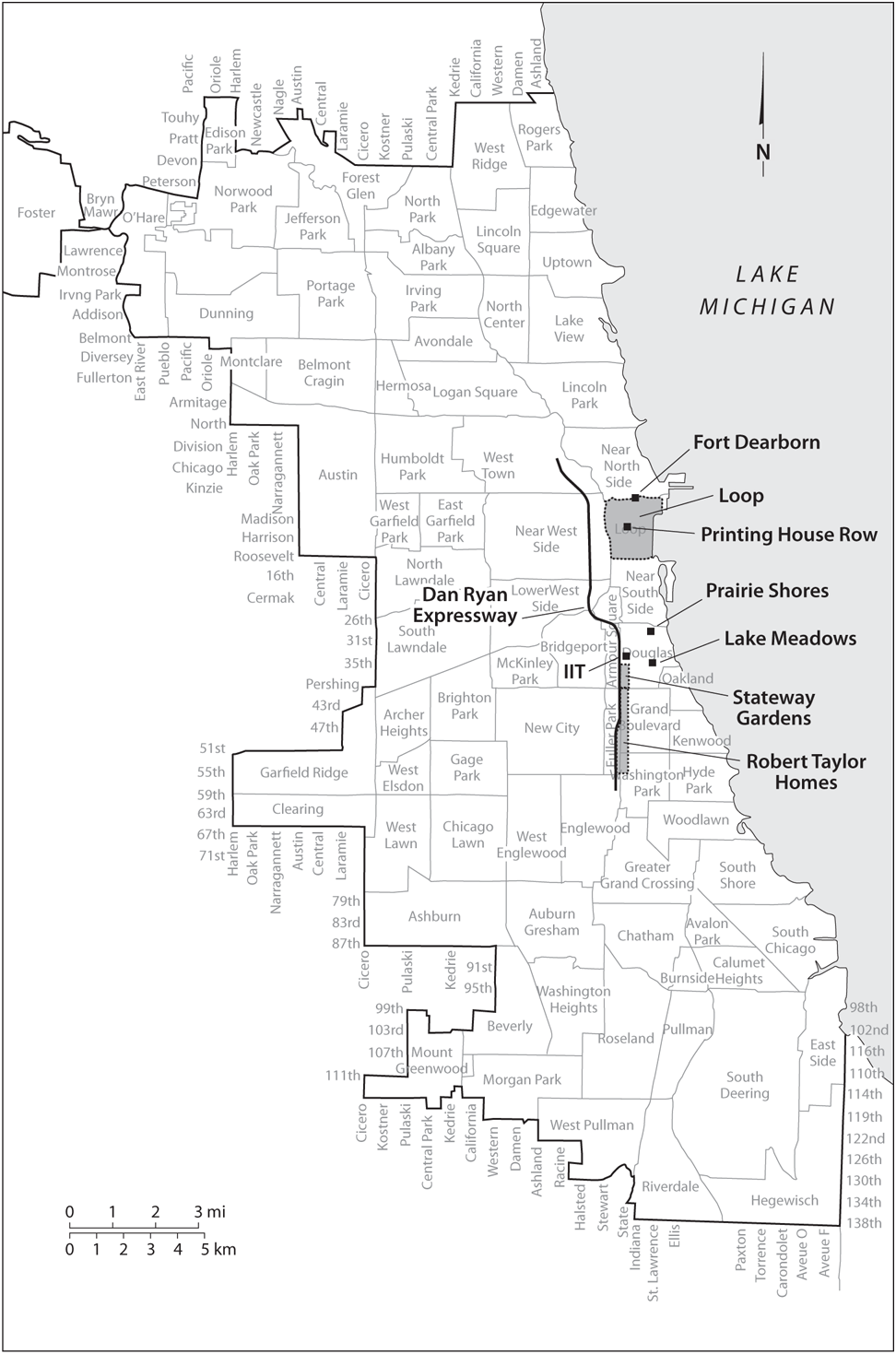

By the end of the 1940s the city was using such powers to begin redeveloping the Near South Side neighborhoods around the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) and the Michael Reese Hospital. Working closely with real estate magnate and MHPC president Ferd Kramer, the city cleared hundreds of acres of slums to make room for two new middle-class housing complexes, Lake Meadows and Prairie Shores, which would end up raising rents around IIT and Michael Reese between 300 and 600 percent—an increase that priced out the vast majority of the mostly black residents who had been displaced.

This first foray into the new postwar frontier of urban renewal did not go so smoothly. Opposition to the Lake Meadows project crystallized soon after the announcement, with property owners filing suit in federal court to prevent the CLCC from taking their homes, and a group called the Property Conservation and Human Rights Committee of Chicago petitioning the federal government to withhold funds. Moreover, the uncertainties surrounding the situation of the thousands of black residents who would be displaced by the project caused considerable political fallout, prompting Third Ward alderman Archibald Carey Jr. to propose a city ordinance, backed by the Chicago Urban League and CORE, outlawing discrimination “where public aid is provided for housing units . . . even though such housing units are built with private funds.” While the ordinance was, in the end, soundly defeated in the city council, it stirred up a rancorous debate, with Carey and other proponents of the measure evoking “negro removal” and comparing the treatment of blacks to that of Jews in Nazi Germany. Sensing the seriousness of the threat to Chicago’s urban renewal plans, Mayor Kennelly, who normally observed a policy of nonintervention in legislative matters, appeared in person before the city council to speak against the ordinance.

Moreover, African Americans residing in the area around Lake Meadows were not the only ones to feel threatened. Late in 1950, with the bulldozers rumbling away, a range of community associations from a number of white South Side neighborhoods, some located several miles away from the Lake Meadows site, began agitating against the project for very different sorts of reasons. Leading the charge was a realtor from the Roseland community who argued that the rehousing of those displaced by the Lake Meadows project posed a “disastrous financial burden” to taxpayers while stoking fears about the “dispersal of the colored inhabitants . . . into outlying areas.”25 Adding to all this trouble and delay was more controversy surrounding the proposal to close a stretch of Cottage Grove Avenue, an idea that the Chicago Plan Commission pondered for several months before finally signing off. By 1950, the New York Life Insurance Company, the project’s principal investor, was threatening to pull out, but Kennelly proved a capable fixer. Nearly two years later ground was finally broken.26

In the end, Lake Meadows was built, and the ultimate success of the project opened the way for a lot more of the same. Emerging out of the wrangling and controversy over Lake Meadows was a new modus operandi for the city’s planning and development process. During this time the MHPC’s downtown agenda prevailed over a range of Loop area interests who favored a very different approach to the future—one that sought to revitalize the neighborhoods surrounding the Loop rather than merely orienting their redevelopment around the priorities of Pettibone, Kramer, Mumford and the rest of the downtown business crowd. Standing opposed to the MHPC, for example, was the South Side Planning Board, an organization that represented a range of manufacturing, printing, and warehousing interests from 12th Street all the way down to 47th Street. Rather than the middle-class residential development favored by the downtown interests to house white-collar workers, provide downtown shoppers, and buffer the Loop against blight, the South Side Planning Board supported infrastructural improvements that would aid the expansion of Near South Side manufacturers, which would, in turn, provide a healthy job base for working-class South Side residents.

A similar campaign against the downtown agenda emerged on the Near West Side in 1949, when the Near West Side Planning Board, with the support of Twentieth Ward alderman Anthony Pistilli, successfully challenged the classification of a part of the neighborhood as blighted and put forward a redevelopment plan that sought to promote local manufacturing activities and to rehabilitate rather than clear existing structures. The back-and-forth between such neighborhood groups and downtown interests continued into 1954 with the announcement of the Fort Dearborn project, which was to involve the clearance of a 151-acre swath of land on the north bank of the Chicago River for the construction of five thousand private middle-income housing units and a $165 million civic center. Almost immediately Near North Side planning groups sprang into action, protesting the classification of the area as blighted and the effects the project would have on the local real estate market. However, just as things were getting unruly, with ordinary residents actually demanding a say in the planning process, Pettibone and Hughston McBain, chairman of the board of Marshall Field’s, moved to build a new and more powerful coalition of downtown business interests, the Chicago Central Area Committee (CAC), that would ultimately save their day.27

And yet the CAC remained restrained in Mayor Kennelly’s Chicago, where the city council actually possessed a legislative function and aldermen allied themselves with local planning groups looking to throw wrenches into the growth machine’s plans. This would change under Daley’s watch. Like Kennelly, Daley, despite all his blathering about defending the neighborhoods against State Street, believed that what was best for Ferd Kramer, Holman Pettibone, and Marshall Field was best for the machine. And he reconfigured city government accordingly. After taming the city council, Daley moved to sever it from the planning process with his creation in 1956 of the Department of City Planning, an agency that would be answerable to him rather than the city council. As a sign of how Daley conceived of the role of the Department of City Planning, he appointed Ira Bach, the former executive director of the CLCC who had worked closely with Pettibone on the Lake Meadows project, as its commissioner. During his years directing the CLCC, Bach had favored relying on the private housing market to rehouse working-class blacks displaced by clearance projects—a dubious notion in Chicago’s segregated housing market—and expressed annoyance about the attempts of federal housing officials to obligate the city to formulate adequate and precisely detailed relocation plans. Taking over the tasks of planning and zoning, the Department of City Planning reduced the meddlesome Chicago Plan Commission into a purely advisory body. One of Daley’s first directives to the department was to instruct it to work with the CAC on a new plan for downtown. The fruit of this collaboration was the 1958 Development Plan for the Central Area of Chicago.

With a board that included the heads of Illinois Central Railroad, United Airlines, Marshall Field & Company, and some of Chicago’s largest banks, it was to nobody’s surprise that the CAC would promote a plan for the downtown area that emphasized increased office development, more expressways and garages, a beautified riverfront, a downtown subway system, a transportation center, near-downtown housing for fifty thousand families, and a University of Illinois campus—all that was necessary for a downtown business district oriented around management, financial services, and retailing. The development plan represented a blueprint for deindustrialization that clearly prioritized real estate values and Loop retail activities over jobs and proper housing for the city’s working class. The plan, the South Side Planning Board predicted, “will tend to drive business from the area to a section of the city where it can feel more secure.”28 Those who invested in such an eventuality made spectacular profits. During the first ten months of 1959, developers bankrolled eight major office and residential building projects with an overall price tag of $130 million, and between 1958 and 1963, construction activities around the Loop amounted to an impressive $662 million.29 One notable victim was the vibrant printing sector housed within the industrial loft buildings around Printing House Row, an area the development plan had designated for “resident reuse.” Between 1960 and 1970, land values here increased by $10 per square foot, after having remained virtually unchanged during the previous decade. Such speculation paved the way for the rapid loft conversion of the 1970s, and by the mid-1980s Printing House Row no longer contained a single firm to justify its name. The impact of such processes on the city’s labor market was nothing less than spectacular. Between 1972 and 1983, Chicago lost some 131,000 manufacturing jobs, roughly 34 percent of its total manufacturing employment.30

If Daley had never once uttered the term neoliberalism, his willingness to hand over the planning of the city’s future development to its business community suggests that he can be considered a kind of proto-neoliberal in a moment rarely characterized as belonging to the history of the neoliberal city. In fact, historians of the “neoliberal turn” have seldom traced its origins back into the 1950s and 1960s. For David Harvey, for example, the history of neoliberalization in the United States begins in New York in the mid-1970s, when, in the midst of a severe budget crisis, a cabal of investment bankers bailed out the city and thereby seized control of its resources and municipal institutions in order to restructure the city according to their entrepreneurial agenda. The result, according to Harvey, was that “city business was increasingly conducted behind closed doors, and the democratic and representational content of local governance diminished.”31 But who could deny that a similar result had not already been achieved in Chicago some two decades earlier?

However, Daley’s embrace of the downtown agenda and his moves to create a governance framework that silenced the grassroots and shifted the planning process into corporate boardrooms were not the only dynamics that were neoliberalizing the city during the 1950s. No less important were the kinds of governance criteria that the downtown business crowd were managing to inscribe within Chicago’s governing institutions—a set of notions that aligned the public interest with their interest and that viewed the primary role of city government as a mechanism to unleash the forces of private enterprise. This phenomenon was hardly unique to Chicago. The protests emerging out of Chicago’s neighborhoods against the downtown agenda reflected a broader struggle taking place in municipalities across the nation over the very definition of blight. Emerging out of the New Deal context, blight during the 1930s was largely synonymous with slum and thus with unsafe and unhealthy conditions of residential living. But by the early 1940s, as state legislatures moved to give legal grounding to the activities of redevelopment agencies, the meaning of blight increasingly began to take on a much more pecuniary character, with key criteria related primarily to proper and productive economic use.32 Those pushing the downtown agenda in Chicago thus evaluated the public-private partnerships that would drive the city’s planning and growth in terms of revenues generated rather than in terms of social benefits created. They generally considered social costs, if they considered them at all, as nuisances to be managed.

Indeed, if, as political theorist Wendy Brown has argued, the advance of neoliberalization has increasingly placed the state “in forthright and direct service to the economy” and reduced it to “an enterprise organized by market rationality,” then the decade between the launch of the Lake Meadows project and the release of the 1958 Development Plan for the Central Area of Chicago was certainly a crucial one in Chicago’s move towards a neoliberal future.33 During this moment, for example, one of the city’s most critical social needs institutions, the Chicago Housing Authority, was transformed from an agency whose mission was providing decent affordable housing to low-income families to what Ferd Kramer described at the time as “the critical key to freeing land for redevelopment by private enterprise.”34 The gutting of such an important institution was accomplished so easily because public housing in Chicago had been thoroughly racialized in the decade following the end of the Second World War, when Elizabeth Wood had tried to use it as a lever of racial integration. Public housing, in the minds of most, was about black people, and, the Carey Ordinance aside, these same people watched helplessly as Boss Dawson and the rest of their political leadership failed to raise much of a stir about the use of their constituents’ tax revenues to finance the displacement of working-class African Americans living in the paths of the bulldozers.

But even though Daley possessed neoliberal sensibilities, the patronage game made him something of a quasi-Keynesian in spirit. Far from being ideologically driven by the notion of cutting budgets and reducing the state, the Daley machine was all about expanding municipal government and spending as much as possible—just as long as it was the federal government and private investors who were footing the bill. To be sure, the mayor’s Keynesian side was devoid of any sort of vision of trickled-down social justice (and here is where the quasi becomes necessary); only the machine’s faithful could share in the wealth, and the others could suffer for their stupidity for all he cared. Rather than social justice, Daley gave Chicagoans city services—cleaner streets, roads without potholes, more extensive police protection, better public transportation—even if such services varied widely according to which side of the color line you lived on. And he used signs, stickers, and highly publicized campaigns to make sure that nobody overlooked all that he was doing for the city.

However, if Daley was eager to entrust an alliance of business interests and technocrats with the task of planning Chicago’s future, preserving the city’s racial order was a job he would often take into his own hands. In reality, his business allies and their planners were mostly after the same thing he was, even if they often articulated their goals in coded, technical terms. In a 1958 urban renewal plan spearheaded by the University of Chicago, for example, the idea of demolishing hundreds of acres of mostly lower-income black housing between 47th Street and 59th Street in Hyde Park was justified in the name of developing a “compatible neighborhood” for the university. Similarly, the CAC’s vision of the Loop’s future lay in promoting middle-class residential communities around it, with the term middle-class serving as a euphemism for white. By the late 1950s there was a clear consensus among Chicago’s most influential developers, realtors, and planners that the creation of white middle-class communities provided the best defense against the rising tide of ghetto blight. They were acting to protect valuable institutions and the value of the real estate around them, and in doing so they were doing the mayor’s bidding, for increasing real estate values meant increasing revenue for the city, and revenue, of course, translated into patronage and power for the machine. This was the beginning of a new period in the history of the American city when the capital generated from the redevelopment of urban space increasingly replaced that derived from manufacturing activities. In the case of Chicago, in particular, the presence of an administration so wedded to this progrowth ideology has caused historians to debate the extent of Mayor Daley’s part in this process, with some of the more persuasive studies arguing that the mayor’s role was more that of “caretaker” than “creator.”35

Certainly, broader structural forces were also driving the move towards a redevelopment approach that ended up privileging the interests of the downtown business elite over any goals of social justice, and Chicago’s land use profiteers were not much different from other big city developers throughout the country in their haste to take advantage of their privileged role in municipal governance. But one would be mistaken to overlook the enormous power that Daley wielded over Chicago’s urban renewal adventure. While developers and planners often hid behind technical language to draft plans that hinged on racial exclusion, the mayor exhibited a will to act boldly and ruthlessly to preserve the city’s segregated racial order. It was a will, one could argue, that developed out of Daley’s years of fighting with the Hamburgers on the front lines of a guerrilla war against racial invasion—a background that distinguished him from other big city mayors of the time. This did not mean that Daley did not choose his words carefully; he understood the civil rights awakening that was in motion, and he was very adept at leaving few public traces of his segregationist ways. And yet his actions spoke much louder than his words.

A prime example was his intervention into the plan to construct the new Dan Ryan Expressway, a badly needed highway that was to serve as a southern route out of the Loop. The Dan Ryan was one among several new highways radiating out of the Loop that the mayor was going to build—a project that created a massive public works boondoggle paid for with federal dollars provided by President Eisenhower’s Interstate and Defense Highway Act of 1956. Few commuters taking the Dan Ryan today think much about the two sharp turns they are forced to make after crossing the Chicago River, but they are a remnant of the race war of position that was being fought in Chicago in the 1950s. These turns were not part of the original plan for the expressway, but after Daley saw that the proposed route would cut his childhood neighborhood of Bridgeport nearly in half, he ordered the planners to shift the road so that it would run right along Wentworth Avenue—the traditional boundary between white and black Chicago on the South Side that Daley’s gang had defended with their fists. But protecting his beloved Bridgeport was only part of the story. Daley’s intervention into the Dan Ryan’s planning came less than a month after the city council had approved the Robert Taylor Homes, and, having just authorized the placement of several thousand black families along State Street, just three blocks east of Wentworth, the mayor was now moving to make sure those families and their black neighbors would keep to their side of the color line. With seven lanes in each direction, the Dan Ryan would form an impenetrable boundary. “It was the most formidable impediment short of an actual wall,” wrote journalists Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor, “that the city could have built to separate the white South Side from the Black Belt.”36

Hence, if critics and even more neutral observers of urban renewal in the 1950s and 1960s often sounded like war reporters, throwing around terms like demolition, no man’s land, razed neighborhoods, and displaced people, that was precisely because urban renewal was a form of warfare. Few people strolling by any of the vast areas cleared out by bulldozers could resist comparisons to the bombed-out European cities of the war years. Were similar events of this scale to take place today, references to “ethnic cleansing” would no doubt be rampant. The fact is that while urban renewal made victims and displaced persons out of immigrants and poor whites along with blacks, the front lines of this war were at the edges of the ghetto, and the fact that the ghetto lay so close to valued real estate called for extraordinary actions at times. In Chicago, the battle to hold the color line required brutal tactics, and Richard J. Daley proved to be the perfect battlefield commander, unflinching in the face of the injuries he was helping to inflict. But a battlefield commander is hardly the ideal person to handle the refugee crisis caused by his actions, which Daley, the builder of the city’s most notorious high-rise housing projects and the numerous new police stations that went with them, was. When the dust had cleared, the city had obliterated a number of vibrant neighborhoods and destroyed more housing units than it had created.

MAP 5. Downtown development and public housing in the 1950s.

STRUGGLING AGAINST THE BULLDOZERS

The massive urban renewal projects of the 1950s and 1960s set Chicago on a whole new course. Deciding whether that course took the city towards a bright or dismal future depends on which Chicago you are talking about. The Chicago one sees when moving north on Michigan Avenue past Millennium Park and its Frank Gehry bandshell, across the river to the Magnificent Mile, swanky retail stores packed with eager shoppers as far as the eye can see, and then on to the ritzy brownstone-lined streets of the Gold Coast, Old Town, Lincoln Park, and Lakeview leads to one conclusion; an encounter with some of the grittier streets of the segregated West Side, where storefront churches and liquor stores are the most conspicuous signs of life in a landscape dominated by litter-strewn vacant lots and boarded-up buildings, leads to quite another. It is hard to imagine today that neighborhoods like North Lawndale and East Garfield Park, both of which lie just minutes west of the Loop, right off the Dwight D. Eisenhower Expressway, were thriving, middle-class districts when Mayor Daley began his first term in office. Yet that was when the fate of such neighborhoods was determined. In the late 1950s, Daley and his allies in the business community decided that these areas should lie on the other side of the barriers they were erecting to insulate the downtown business district from the rapidly expanding black ghetto. This decision was made, in fact, as these very same communities were in the process of becoming the blighted ghetto that everyone feared. In the 1950s, whites began to flee these areas as if they were escaping a flood or some other natural disaster, transforming the population from overwhelmingly white to predominantly black in the span of less than a decade. North Lawndale’s demographic transformation was the most dramatic of all, shifting from 87 percent white to 91 percent black between 1950 and 1960. What was a middle-class mix of Jews, Poles, and Czechs became a lower-income black ghetto seemingly overnight, a movement of people that was quickly followed by a migration of viable businesses and decent jobs out of the area. Studying the structural conditions behind the social distress of young blacks in this area in the 1980s, then University of Chicago sociologist William Julius Wilson found, astonishingly, that while the area provided just one bank and one supermarket for a population of 66,000, it possessed no less than 99 bars and liquor stores and 48 lottery vendors.37

What was happening in North Lawndale resembled the situation in a number of areas south of the Loop as well, such as Woodlawn and Englewood, and the incredible rapidity with which such neighborhoods were transitioning from stable middle-class settings to depressed slums weighed heavily upon the minds of the business leaders and city officials who drafted Chicago’s 1958 development plan. It weighed even more heavily upon the spirits of residents of these areas, who looked into the eyes of the young around them and saw frustration and disillusionment staring back. After happening upon a group of teens shooting pool during school hours one day in her South Side neighborhood, Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Gwendolyn Brooks reflected upon this precocious fatalism in her famed poem “We Real Cool,” a short stanza that reads like an autobiographical epitaph concluding with the brutally simple words “We die soon.”38

By 1960 African Americans constituted nearly a quarter of Chicago’s population, and the migration of southern blacks into the city was showing no signs of letting up. In the face of such circumstances, downtown boosters looked to use as many physical and social barriers they could muster to insulate the central business district from the encroaching ghetto. Physical barriers included expressways, new government buildings and housing developments, and, perhaps most importantly, a new campus for the University of Illinois; social barriers would be constituted out of the new middle-class and upscale residential communities that would develop around these new structures. The objective was not only to keep the ghetto out but also to keep the exploding population of suburban commuters shopping and otherwise amusing themselves downtown. Race was never mentioned in the plan—the mayor himself ordered that it not be—but, in a city with such a negligible presence of upwardly mobile middle-class blacks, the idea of catering to the needs of middle-class residents, so often evoked in city planning discourse, was unambiguously segregationist.

This did not mean, though, that working-class whites escaped the bulldozers unscathed. If Chicago was aspiring to be the most segregated city in the United States, the goal, at least by the early 1960s, had hardly been achieved in several areas north, northwest, and west of the Loop, where black neighborhoods lay close to communities of Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Italians, and Poles. About seventy thousand blacks, for example, lived in the relatively integrated Near West Side neighborhood area, particularly in and around the Jane Addams Homes, Robert Brooks Homes, and Grace Abbott Homes projects, just a few blocks below Little Italy’s main drag along Taylor Street. For the coalition of developers and downtown business interests behind Chicago’s 1958 plan, this high crime and delinquency district, so perilously close to the Loop’s lower western flank, was a force to be reckoned with. But in view of the relatively large scale required for the development of any kind of effective buffer between the gritty streets of the Near West Side and the suits and skyscrapers of the Loop, the solution to the problem would necessarily involve the destruction of the neighboring community, which consisted of a multiethnic mix of Italians, Greeks, Jews, Mexicans, blacks, and Puerto Ricans. To be sure, this neighborhood was hardly a model of ethnic pluralism—the Italians had long monopolized the area’s political machinery, street gangs divided along racial and ethnic lines, many bars and restaurants were off limits to certain groups, and discriminatory practices by realtors and landlords meant that blacks and Puerto Ricans almost never lived in the same buildings as whites of European descent. And yet, if this neighborhood lacked cohesion and if its housing stock was a bit dilapidated, it was far from being a stagnant slum with little hope for the future. Storefronts were generally occupied, local associations were relatively numerous, and the area possessed a vibrant street life, replete with lemon ice vendors, Italian beef and sausage joints, and pizza parlors. In short, this area hardly fit the profile of a slum to be cleared at any cost, and yet it would be cleared anyhow, if not without a fight, so that the downtown business crowd could have its wish—a new branch of the University of Illinois to buffer the Loop against the swelling ghetto to its west.

Such circumstances explain why it would be here, between 1959 and 1962, that a scrappy movement of citizens would become the first real thorn in the side of the growth juggernaut. Some vocal resistance to urban renewal had manifested itself a year earlier, when the Hyde Park chapter of the NAACP had raised objections to the University of Chicago’s plan to demolish more than 20 percent of the housing in an 855-acre stretch of land between 47th and 59th Street—a scheme that would have displaced thousands of black families, raised rents in the area, and effectively whitened the community (which is precisely what eventually happened). But the campaign had fizzled out when the Hyde Park chapter of the NAACP, under pressure from the Chicago NAACP’s pro-machine leadership, pulled out.

On the Near West Side, however, the battle against urban renewal would take a very different course, with thousands of residents, mostly women, demonstrating in the streets holding signs emblazoned with such slogans as “Daley Is a Dictator.”39 The mobilization of the Near West Side’s Harrison-Halsted Community Group in response to the city’s intention to acquire 155 acres for the construction of a new university represented one of the first in a wave of similar protests that questioned the legitimacy of urban renewal plans that advanced the cause of downtown commercial development at the expense of working-class residents.40 In the case of the site selection for Chicago’s new campus, the subordination of neighborhood interests to those of the downtown business elite was particularly blatant because an earlier plan to locate the campus in the East Garfield Park area had elicited enthusiastic support from both university trustees and community leaders, who viewed the university as a bulwark against the area’s transformation into a black ghetto. Here was an idea that seemed to fit a much more democratic conception of what should be at stake in urban renewal—democratic not only in the sense that it would have redistributed resources to the average residents of a neighborhood badly in need of help but also in its potential support for the cause of racial democracy. As the primary public university in the metropolitan Chicago area, the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) was destined to attract a racially diverse student body and staff, which made it the perfect cure for a community in the throes of rapid racial transition. But in the end, the pleas of Garfield Park and the protests of the Near West Side fell on deaf ears. As the Harrison-Halsted organization was filing last-ditch appeals to the city’s plan, its leader, a housewife turned activist named Florence Scala, met with the mayor to ask that residents, many of them elderly, be allowed to remain in their homes until the appeals were ruled upon. Daley denied the request and began evictions the next day.

Yet if Mayor Daley ultimately brushed aside Scala’s Harrison-Halsted organization without much trouble, the mobilization of Near West Side mothers embodied a new spirit of activism and a new will to frontally take on the sources of power behind the policies that were reshaping the city. In some sense, these angry moms rallying to preserve their families and their neighborhoods looked much like the mothers who had joined the ranks of racist mobs in years past for—to their minds—very similar reasons. In the protests against racial integration at both the Airport Homes and the Trumbull Homes, observers had noted with some surprise the very active participation of women, often with small children in tow. On both these occasions, much like numerous other such incidents around this time, protestors expressed not only hatred for their dark-skinned potential neighbors but also a populist-inflected anger against a city government that seemed to be conspiring against their families, their communities, and their property values. In challenging the machine’s undemocratic manner of decision making, the Harrison-Halsted organization was also drawing upon another more progressive legacy of political activism that had taken root in Chicago with the pioneering efforts of community organizing virtuoso Saul Alinsky in the early 1940s.

The Harrison-Halsted organization was not the only grassroots organization challenging the Daley machine’s growth agenda in this moment. About eight miles south of the UIC site, just to the east of the Dan Ryan, citizens in the black working-class area of Woodlawn were also coming together to oppose an urban renewal plan that threatened to wipe away their neighborhood to make way for another of the city’s institutions of higher learning, the prestigious University of Chicago (UC). With the bulldozers plowing away in Hyde Park, the university’s leadership, guided by fervent urban renewal advocate Julian Levi, devised another big urban renewal play that would further stabilize its environs by displacing lower-income black people. Initially constructed to hold the world’s first Ferris wheel, a replica “street in Cairo,” and a number of other carnival attractions for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, a one-block-wide grassy strip known as the Midway (originally called the Midway Plaisance) had been buffering the university from the ghetto streets of Woodlawn since the 1940s. But by the late 1950s complaints of muggings around the Midway were proliferating. Seeking to push the ghetto further from its pristine Gothic walls and manicured lawns, the university announced a new plan to convert a mile-long strip just south of the Midway into a new South Campus for the university. Thousands of black families would be evicted from their homes and, as usual, nobody was saying much about where they would end up, but the mayor could not have been more on board with the plan. Daley was convinced by Levi’s argument that this was “the moment of truth” for the neighborhood—“the moment when assets and liabilities have to be cast up, when what is wrong and what is right has to be defined.”41 Due to Levi’s lobbying efforts in Washington, moreover, Congress had passed new legislation in 1959 that gave the city enormous financial incentives for supporting such projects; if all went as planned, the university’s spending on the South Campus project would generate an estimated $21 million in federal urban renewal credits that could be used anywhere within the city limits. In other words, the whole affair was looking a lot like a fait accompli.

The idea of organizing residents in Woodlawn to take on the University of Chicago and City Hall over this plan thus represented a David-versus-Goliath scenario. If no time was a good time to take on the Daley machine, now was worse than ever. By the start of 1961, the mayor seemed invincible. Not only had he won reelection two years earlier with a near-record 71 percent of the vote, but he had also played a critical role in winning the presidency for John F. Kennedy, the nation’s first Catholic president, in 1960. In the tightest presidential election of the twentieth century Kennedy had carried the key swing state of Illinois by a mere 8,858 votes out of the 4,657,394 cast, but, with Daley getting out the vote in the machine’s strongholds, he had amassed a 456,312-vote margin in Chicago. Allegations of improprieties and lawsuits followed, but such suspicions only boosted Daley’s new political capital with the president—Daley was a kingmaker, and Kennedy would surely be taking his phone calls.

But Chicago had in its midst the kind of larger-than-life figure who relished this situation, and the story that was unraveling in Woodlawn in 1961 fit his larger agenda perfectly. Radical community organizer Saul Alinsky had already won accolades from progressives all over the country for his efforts in overcoming the intense ethnoracial conflicts that had divided residents living in the downtrodden, smelly neighborhoods around Chicago’s stockyards in the early 1940s. With the moral support of the Archdiocese of Chicago in the form of renegade Bishop Bernard Sheil and the financial support of enlightened philanthropists like Marshall Field, Alinsky had led a bare-knuckle campaign to unify Poles, Lithuanians, Slovaks, Bohemians, and Mexicans within a grassroots democratic organization known as the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (BYNC). The immediate objectives were to fight against poor housing and health conditions, malnutrition, and juvenile delinquency, but the project fit into a much broader framework in Alinsky’s eyes. “This organization,” he had written during the BYNC’s first days, “is founded for the purpose of uniting all of the organizations within the community . . . in order to promote the welfare of all residents . . . regardless of their race, color, or creed, so that they may all have the opportunity to find health, happiness and security through the democratic way of life.”42 Reflecting on the BYNC’s impressive achievements on these fronts in the first years of its existence, the Chicago Daily Times referred to the organization as a “miracle of democracy,” and New York’s Herald Tribune claimed the spread of Alinsky’s methods to other cities “may well mean the salvation of our way of life.”43 Moreover, these efforts at participatory democracy attracted the attention of the French Thomist philosopher Jacques Maritain, who struck up a close friendship with Alinsky during his wartime exile in the United States. It was Maritain, in fact, who convinced Alinsky to write his first book, Reveille for Radicals, which built upon his organizing experiences in the Back of the Yards to argue for the need for radicals throughout the country to form such “People’s Organizations” and to present them with the strategies for doing so. Faced with the rise of fascism in Europe and the Nazi occupation of his country, Maritain saw Alinsky’s work as a means of bringing about the democratic dream of people working out their own destiny. As Maritain argued in 1945, organizations like the BYNC could produce an “awakening to the elementary requirements of true political life,” which would, in turn, lead individuals to experience “an internal moral awakening.”44