FIVE

Civil Rights in the Multiracial City

WEST SIDE STORY

Few people felt the heat on Chicago’s streets in the summer of 1963 as intensely as Frank Carney. The weather was typical for that time of year—unrelenting heat and humidity, with overnight lows that never dropped enough to cool things off before the blazing sun rose again. But for Carney, the supervisor of a regiment of youth workers on the city’s Near West Side, the heat rose as much from the friction of clashing teenage bodies as it did from the pavement. Making his rounds of the neighborhood to gather information, Carney listened to stories about black and white youths throwing rocks at each other around the Holy Family Church on Roosevelt, tensions between Mexican and Italian gangs around 18th Street, Puerto Ricans and Italians scuffling at Little Italy’s summer carnival, and Puerto Ricans attacking blacks around St. Jarlath’s Church at the corner of Hermitage and Jackson. Speaking with the priests over at this church, Carney wondered to himself why Puerto Ricans who knew little of such racial antagonism in Puerto Rico would so readily pick it up here. After the interview, he decided to assign one of his youth workers to, as he noted in his report for the day, “cultivate a relationship with the Puerto Ricans who hang out on the corner of Jackson and Wolcott.”1 This was damage control—not nearly enough to change the situation—but it might keep a lid on things for a while.

Carney worked for the Chicago Youth Development Project (CYDP), a delinquency prevention and research program experimenting with a new approach to keeping youths out of trouble. Whereas most programs in the past had been based around the idea of drawing youths into local clubs and community associations by offering various recreational resources—sports facilities or halls for dances, for example—the CYDP was trying out a more aggressive strategy. What youth workers in previous delinquency initiatives had discovered was that the teens who were most in need of guidance kept away from the institutions that were attempting to serve them. The CYDP thus sought to move its “extension workers” out into the streets and parks to become acquainted with the more hardened youths; ideally the extension worker would be young and indigenous to the neighborhood—someone who had the kind of swagger and street cred that would enable him to win the respect of the youths he was trying to reach. However, Carney and his crew would very rapidly discover that the task of preventing juvenile delinquency was almost indistinguishable from that of managing the tense relations between the different ethnoracial groups sharing the streets, parks, snack joints, dance halls, and movie theaters of the multiethnic Near West Side.

Somewhat ironically, when the CYDP began operations out of its Near West Side “Outpost,” as its staff referred to it, crowds were lining up at cinemas everywhere to see West Side Story—the Academy Award–winning film whose visions of white and brown street toughs pirouetting and jumping in the mean streets of a New York City slum made it the second highest grossing film of 1961. While the experience of dealing with the daily threat of homicidal violence in the real world of Chicago’s Near West Side no doubt made CYDP’s workers somewhat jaded about such glamorized renditions of violence, poverty, and racism, few could deny that the film’s tale of hate and love between Puerto Rican and Italian youths bore some resemblance to the dramas they were encountering. Yet, if the enormous popularity of West Side Story had something to do with its dazzling choreography, electrifying Leonard Bernstein score, and Natalie Wood’s stunning beauty, it also reflected a fascination with the nation’s “troubled” younger generation. In fact, images of wild youths had filled the screens of American theaters since 1955, the year of such provocative films about delinquency as The Blackboard Jungle and Rebel Without a Cause. This was the same year in which Bill Haley and the Comets’ Rock Around the Clock shot to the top of the pop charts, and RCA signaled rock ’n’ roll’s takeover of the popular music industry by signing Elvis Presley to a recording contract. The image of the dangerous teen was thereafter coupled with the menacing sounds of rock music droning in the background from some far-off jukebox or transistor radio.

Such trends had touched down in Chicago in July 1955 in the form of a media-induced panic about the subculture of deadly gang violence in the city’s working-class districts. The defining event was a gang of toughs from Bridgeport gunning down a teen in front of a snack joint, an incident that prompted the Tribune to run an investigative series on “youth gangs and the juvenile delinquency problem.”2 Several months later, after a fatal stabbing and vicious gang attack hit the papers in the span of three days, the Daily News reported that Chicago youths were increasingly falling under the influence of a “wolf-pack complex.”3 In response, the YMCA announced plans to infiltrate gangs with “secret agents,” and Mayor Daley, who had expanded the ranks of the police department’s juvenile bureau by nearly 50 percent since his recent election, urged stricter enforcement of the city curfew law while reassuring Chicagoans that “our young people are good.”4

These events coincided with an epidemic of racial violence along Chicago’s color line, and, while evidence of the leading role played by youths in the defense of neighborhood boundaries had been mounting since the war years, the local press marshaled the jargon of social psychology and popular beliefs about lower-class gangster pathology to explain the problem at hand. Juvenile delinquency, in this view, was merely the stuff of “grudge killings” and “gang feuds” perpetrated by young men afflicted by “gang complexes,” “feelings of inadequacy,” and “misguided bravado.” Although James Dean’s gripping portrayal of a troubled suburban teen in Rebel had demonstrated that delinquency could just as easily strike middle-class America, the delinquency issue in Chicago came across as it had in the past—as a manifestation of working-class life. The black press, on the other hand, had a very different perspective. When the Chicago Defender printed a front-page editorial entitled “Juvenile Terrorism Must Be Stopped” in the spring of 1957, its editors were referring not to gangland grudge killings but rather to a “wave of crimes and violence” that was, they claimed, “paralyzing social relations and hampering normal race relations.”5 The main incident prompting their call to Mayor Daley for a “citywide emergency committee” came in March 1957, when twelve teens belonging to a predominantly Polish Englewood-area gang known as the Rebels surrounded a seventeen-year-old African American named Alvin Palmer and one of their members landed a fatal blow to his head with a ball-peen hammer.

Palmer’s slaying awakened the city to the gravity of its racial problem, and to the deep implication of its young within it. Startling to many was the utter banality of the whole affair. The Rebels were not killers—they were not even high school dropouts—but rather ordinary teens from the Back of the Yards area who had never been in any real trouble with the law before. And yet, despite the chilling senselessness of the Palmer murder, Chicago—its political leadership, its news media, and its citizens—was still far from any public reckoning of the simmering racial tensions in its streets or of any policy response to the conditions producing them. With most of the city turning its back on the interrelated problems of neighborhood transition and racial conflict, young men on both sides of the color line began taking things into their own hands and acting in ways that, in their collective and concerted nature, began to have some political implications. The summer after the Palmer murder, for example, several thousand white youths rioted in Calumet Park, not far from the Trumbull Park Homes on the city’s Far South Side, in a demonstration against the use of the park by African Americans. Eyewitnesses reported rioters waving white flags or tying them to the radio antennas of their cars and singing racist chants. Police officials monitoring such events spoke of large street gangs rallying youths to the scene, and of white gangs from different parts of the city coordinating their actions.

While few at the time may have viewed such events as constituting anything resembling a social movement in the making, the task of explaining how a crowd of some seven thousand mostly young white men could have materialized so quickly moves us towards the kinds of theoretical perspectives offered by sociologists seeking to understand the structures and networks that mobilize large groups of people to action, and the cultures and identities that make individuals feel themselves to belong to the groups acting.6 Here, in Chicago, youth gang subcultures had exploded throughout the city’s working-class districts, replete with the black leather jackets, white T-shirts, slicked-back hairstyles, and spirit of nihilism that had become the signifiers of youth rebellion throughout the nation. But in the context of the city’s shifting racial geography, the youthful angst and anger that circulated through these subcultures was directed as much at rival ethnoracial groups as it was at sources of adult authority. The gangs that had brought thousands of youths into Calumet Park had been organized to protect neighborhood boundaries, and they shared a common identity of whiteness that they ritualized with flags, banners, and racist songs. While no doubt unaware of it, these youths were the foot soldiers of a broader grassroots movement to defend white identity and privilege that was just starting to rise up as black demands for integration and equality were growing more vocal.

With every rock thrown and every insult shouted, the black will to resist grew stronger. The white youth movement that was crystallizing stood dialectically opposed to a black one feeding off the anger produced by the everyday indignities its members faced at the hands of white gangs and the police. Until somewhat recently, historians of the civil rights struggle in the urban North have tended to overlook such dynamics because of a tendency to employ top-down perspectives that placed the actions of mass-based organizations and the pronouncements of great leaders at the center of the story. Even if some fine studies have contributed to changing that view over the past decade or so, most still view the history of the civil rights movement as beginning in the South in the mid-1950s under the aegis of Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and then moving north in the mid-1960s, where it was derailed by the allegedly destructive influences of the Black Panther Party and divisive Black Power leaders like Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and H. Rap Brown.7 Despite the best efforts of scholars, the collective memory of the civil rights struggle still thinks in tidy dualities—Martin and Malcolm, rights and power, nonviolence and violence, integration and separatism—that tend to oversimplify what was actually a very messy interplay of ideologies and organizations.

To be sure, Martin Luther King did move his people to Chicago in 1966 to take on the problem of northern de facto segregation—that much is true. But black youths in the city were hardly waiting around to be led; they were already organizing to defend their civil rights many years before their city became a key battleground in the nationwide mobilization for rights. Throughout the 1950s, groups of blacks youths—sometimes affiliated with gangs, sometimes just cliques of kids from the same block or school—frequently took on white aggressors attempting to prevent them from using parks, beaches, swimming pools, and streets. By the beginning of the next decade, such actions began to take more organized form. In July 1961, for example, some two thousand black youths participated in “wade-ins” organized by the local branch of the NAACP Youth Council at Rainbow Beach around 76th Street. Perhaps even more impressive than such demonstrations, however, were the much more frequent informal protest actions that characterized these years. A stunning example occurred in June 1962, when in the midst of a series of racist attacks against black students on the city’s Near West Side, over one thousand African American students from Crane High School staged a remarkable march through the heart of Little Italy—a street normally off limits to blacks. While youth workers and scores of policemen were alerted to help prevent a riot from erupting, the youths walked in an orderly procession, school books in hands, without any sign of provocation towards the mainly white onlookers—a nonviolent demonstration that surely drew its inspiration from the courageous southern sit-ins that had recently been carried out by the young members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). This event would not make it into the newspapers—the only reason we know it happened is because Frank Carney recorded it in his daily report log—but its assertion of black solidarity and resolve would certainly be remembered in the area for months to come.8

And yet as most of the city’s youth workers knew all too well, things were not always so orderly out on Chicago’s streets—far from it. Although young black Chicagoans were beginning to exhibit a growing awareness of their role in the broader struggle for civil rights, many youths nonetheless continued to live by codes of the street that were shaped by powerful structural conditions: periodic recessions that ravaged the labor market, massive urban renewal projects that tore up communities and displaced their inhabitants, and demographic forces of flight and migration that transformed the composition of neighborhoods with breathtaking rapidity. By the early 1960s, these circumstances had produced two broader interrelated trends that defined the street cultures of many working-class areas, especially those on the city’s ethnoracially diverse West Side. The first was an escalation in the intensity and stakes of racial aggression that reflected both the increasing use of firearms and a dogged fixation on the presence of racial others. The second was the widespread emergence of fairly large (between fifty and one hundred members) ethnoracially defined street gangs—commonly referred to by youth workers as “fighting gangs”—whose principal function was to engage in potentially deadly combat against rival groups.

Chicago was not alone in this second development. Historians have documented similar trends in New York around the same period, showing how fighting-gang subcultures there developed within the context of deindustrialization, urban renewal, and racial marginalization. But according to one study of postwar New York, violence between opposing gangs was more about controlling territory than it was about ethnoracial conflict.9 Certainly the protection of “turf” was also a driving force in Chicago, but here turf was usually a euphemism for community, and community was often defined in ethnoracial terms.10 Geographers building upon the theoretical frameworks introduced by geographer Henri Lefebvre have drawn attention to the ways in which groups “produce” or define space through their everyday activities.11 Youth gangs in Chicago had been principal actors in this process since at least the late nineteenth century, playing a key role in creating a patchwork of ethnoracial neighborhoods. And ethnoracial identities played a defining role in the politics of everyday life—in telling people who they were and where they stood—because, at least in part, these very identities were physically inscribed within the city’s geography. Characterizing urban social movements in the 1960s and 1970s, sociologist Manuel Castells has observed that “when people find themselves unable to control the world, they simply shrink the world to the size of their community”—an idea that seems particularly well suited to understanding what fighting gangs were, on an instinctive level, trying to accomplish as they defended neighborhood boundaries amidst the racial and spatial turbulence of Chicago of this same era.12

FIGURE 10. White gang members standing watch on a Near Northwest Side corner as a youth worker looks nervously over his shoulder, ca. 1961. Courtesy of Lorine Hughes and James Short.

But the forces that propelled young men impetuously into rumbles against enemies armed with lethal weapons like guns, knives, and bats went beyond ethnoracial pride and prejudice. The violent confrontations they provoked and joined also involved a search for respect and honor when such values were becoming harder to find in the workplace. Between 1955 and 1963, the Chicago metropolitan area lost some 131,000 jobs (or 22 percent) as the number of potential job seekers increased by some 300,000.13 While this period is often considered to be one of national prosperity, Chicago employment figures indicate a slump-and-boom pattern of economic growth that tended to make the labor market precarious for young workers. Recessions struck the city especially hard in 1958 and 1961, causing sharp spikes in unemployment. Moreover, by the early 1960s Chicago was feeling the effects of the larger process of deindustrialization that was beginning to transform labor markets across the old steel belt of the urban Midwest.

One now needed a connection to land the kind of good union job on a factory floor that had provided the previous generation with a decent living and the sense of manliness that comes with working around heavy machines in the company of men; much more available to the generation coming of age in the 1960s were the low-wage, unskilled jobs being offered by hotels, restaurants, and retail stores. Making matters even worse, these labor market conditions coincided with massive clearance and renewal projects on the Near West and South Sides of the city to make way for the construction of giant public housing complexes, new medical facilities around the Cook County Hospital, and the new Chicago campus of the University of Illinois. Describing the Near West Side area in February 1961, Frank Carney offered a stark vision of the situation faced by area residents remaining there: “Many men are in evidence on the streets and street corners when it is warm enough. The emptiness of certain sections resulting from land clearance increases the generally depressing atmosphere.” “It is impossible,” he concluded, “to escape the feeling that the area is on its way out.”14

In addition to industrial decline, labor market volatility, and the social dislocations caused by urban renewal, the forces of postwar racial migration heightened the uncertainties working-class youths felt and shaped their responses to the predicaments they faced. The ethnoracial demographics of the metropolitan United States would be transformed in the 1970s after the passage of the landmark Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, when new family reunification entitlements would open the floodgates to immigration from Asia and Latin America. But Chicago stood apart from many other major cities in that migration flows from both the American South and Latin America had already been altering its racial geography back in the 1950s and 1960s. Constituting just over 14 percent of the city’s population in 1950, the steady flow of African American migrants from the South increased their share of the population to over one quarter by 1962. Paralleling this steady black migration were the waves of Mexican and Puerto Rican immigrants in the 1950s and 1960s. After increasing some 43 percent between 1940 and 1950, the number of Mexicans in Chicago grew almost fivefold between 1950 and 1970 (from 24,000 to 108,000). In this same period, the city’s overall Spanish-speaking population increased from 35,000 to 247,000, while the total population of the city dropped from 3,600,000 to 3,300,000.15 These large migratory flows of Latin Americans complicate the idea, evoked most notably in Arnold Hirsch’s classic study Making the Second Ghetto, that the 1950s was a moment of racial consolidation, the end of a long process of black ghettoization that reinforced the idea of a black-white binary racial order. While one could speak of a universally recognized “color line” separating black from white in previous decades, the situation had become much more complex by the early 1960s, especially on Chicago’s West Side, which had become a mosaic of black, Puerto Rican, Mexican, and white neighborhoods. In this context whiteness and blackness seemed stable enough. African Americans knew they had few friends outside the boundaries of their neighborhoods, and although the Irish still muttered words like guineas and greasers when they crossed paths with Italians at late-night Polish sausage stands, by the end of the 1950s European Americans of all origins could feel secure in their identification with whiteness. The situation was quite different for Puerto Ricans and Mexicans, who were forced to navigate an unpredictable course between blackness and whiteness.

As recent newcomers to the city, Puerto Ricans, in particular, faced some of the most formidable challenges in their efforts to integrate into the city’s housing and labor markets. While New York City was the primary destination for Puerto Ricans leaving the island for city life on the mainland in the 1930s and 1940s, by the early 1950s several small Puerto Rican communities were becoming visible to the north and west of the Loop, especially in Lincoln Park, Lakeview, the Near West Side, Woodlawn, and East and West Garfield Park.16 By the early 1960s, however, the Puerto Rican population was consolidating into two main sectors of the city: the lower Lincoln Park neighborhood on the North Side and a large area to the Loop’s northwest that stretched westward from the community area of West Town into the neighborhood of Humboldt Park, with its main drag along Division Street. Scholars seeking to explain the factors behind such swift internal migrations often refer to “push” and “pull” dynamics—the forces of racial discrimination that pushed migrants into certain areas and the cultural forces that pulled them towards people with whom they felt strong affinities. In reality, these two sides of the story are difficult to separate. While it is hardly surprising that Puerto Ricans arriving in Chicago in the 1950s and 1960s would gravitate towards areas where Spanish was spoken, where plantains could be easily procured to mash into the garlicky comfort food mofongo, and where friends and neighbors could share stories and reminiscences about the island, the flight to the familiar is often, in some sense, a flight from the unfamiliar. The development of a concentrated Puerto Rican barrio along Division Street in the mid-1960s said something about the new spirit of “Boricua” pride and solidarity circulating within the community, but it said just as much about the climate of racial hostility—the insults, the hard stares, and the acts of physical aggression—that Puerto Ricans dealt with on a daily basis. The decision of so many Puerto Ricans to opt for a home in the West Town/Humboldt Park area during the 1960s suggested that, even after almost two decades in the city, few expected this climate to change.

Some Puerto Ricans relocating to the barrio during these years were displaced by urban renewal projects, particularly on the Near West Side, but many more were swept there by the currents of white flight, as entire neighborhoods on the West and South Sides transformed into black ghettos at breakneck speed. Puerto Ricans fled along with European Americans from their black neighbors, but they had quite different motivations. A good many Puerto Ricans, in fact, were Afro–Puerto Ricans whose ancestors had been brought to the island as slaves, and Chicagoans tended to identify them with African Americans. Reflecting on this situation, one Puerto Rican immigrant in Chicago recounted a story of being refused service at a bar on the grounds that he was black. When he responded that he was Puerto Rican, the bartender yelled back, “That’s the same shit.”17 This incident was part of a larger process of “racialization” that forced Puerto Ricans to compete with blacks for housing in the lowest-rent neighborhoods and for work in the lowest-paying sectors of the labor market. Moreover, discriminatory practices by realtors and landlords relegated many of Chicago’s Puerto Ricans to the fringes of black ghetto neighborhoods, where, in some cases, they very quickly found themselves serving as buffers between white and black.

Even if whites tolerated Puerto Ricans somewhat more than their black neighbors, a wave of vicious attacks against Puerto Ricans on the West Side in the mid-1950s left little doubt about which side of the color line most whites felt they belonged. In West Town, where Italian and Polish residents commonly referred to their Puerto Rican neighbors as “colored,” a series of fatal arson fires struck low-rent buildings housing Puerto Ricans, and along the Near West Side’s northern boundary, Italian and Mexican gangs led the resistance against Puerto Rican settlement with repeated beatings.18 Such circumstances explain a great deal about why Puerto Ricans would close ranks by transforming a section of the famed Division Street into a vibrant barrio that would, by 1980, contain almost half the Puerto Ricans in the entire city. But Puerto Ricans moved not only to escape the antagonism of their white neighbors but also because they understood that their proximity to blacks—racially and spatially—had placed them in a precarious position.

Historian Robert Orsi’s concept of a “strategy of alterity” provides an apt way to describe the Puerto Ricans’ tendency to put distance between themselves and African Americans.19 Nor was residential location the only tactic they pursued. According to a 1960 report on the city’s Puerto Rican community conducted by the Chicago Commission on Human Relations (CCHR), dark-skinned Puerto Ricans adopted a range of behavioral tactics to mark themselves off from African Americans. “The dark Puerto Rican,” the authors of this study concluded after hundreds of interviews, “develops unique defensive attitudes in order not to be taken for an American Negro; thus he will speak only a bare minimum of English, trying to convey the impression that he is a foreigner rather than a Negro.”20 But this tendency to use the Spanish language to distinguish themselves from blacks also pushed them closer to their Mexican neighbors, who, themselves, began to engage in their own strategies of alterity.

Mexicans, for their part, had also served as buffers between white and black in parts of the Near West Side as well as in the South Chicago community area around the Illinois Steel mill, and there is ample historical evidence that Mexican youths were active participants in the gang and mob attacks against blacks in these areas.21 Yet Mexicans were second-class citizens in the society of whiteness, and, as such, were the targets of racial hate in the 1950s and 1960s. One poignant example of anti-Mexican aggression during these years occurred when a group of youths mistook a Native American family for Mexicans and repeatedly stoned their East Garfield Park home, once leaving a note pinned to the door that read, “Ha Mex, get out of here”—signed by “the Whites.”22

Such circumstances explain why, when Puerto Ricans were moving en masse into the West Town/Humboldt Park area, Mexicans were gravitating towards the Pilsen neighborhood between 18th Street and 22nd Street, which by the mid-1970s had become the unequivocal center of Chicago’s Mexican community. Once again urban renewal played its part, with the construction of the new UIC campus essentially wiping out what had been a substantial and long-standing Near West Side Mexican community. For decades, Mexicans and Italians on the Near West Side had shared—if at times grudgingly—parks, streets, and community centers. Similarly, in the South Chicago area, the children of Polish and Mexican steelworkers mingled, played, flirted, and sometimes scrapped in the streets and schoolyards. Mexicans had arrived in Chicago in the early years of the twentieth century seeking work on the railroads and in the steel mills and packinghouses. Although they had earned the enmity of many when the bosses employed them as strikebreakers to break the organizing efforts of steelworkers, by the 1930s they had founded newspapers, tortilla factories, restaurants, bodegas, and Spanish-language newspapers. To be sure, they lived in ethnic enclaves—colonias, so to speak—but by the 1950s they were well on the path towards integration. However, the demographic shift around this time constituted a rather significant bump in the road. Established Mexicans quickly found themselves being reracialized by the arrival into their neighborhoods of both Puerto Ricans and Mexican immigrants who spoke little English and knew nothing of American ways. Although in 1957 Mexican faces were conspicuous amidst the mobs of youths rallying around white supremacy in Calumet Park, many Mexicans seemed less certain of their place in the ranks of whiteness in the following years—a situation revealed poignantly in the early 1970s when activists in Pilsen began using the term la raza to designate the Mexican community.

Indeed, just as a color changes in relation to which colors surround it, the racial identity of Mexicans seemed to change in a city with increasing numbers of African Americans, Puerto Ricans, and Mexicans themselves. In a matter of years, the ethnoracial identities that had taken shape along the interfaces between Puerto Rican, Mexican, black, and white would be called forth in the name of political movements demanding rights, equality, justice, and power. Those rallying behind these identities would, at times, look outside their communities to build bridges with others around universalistic notions of class justice—Chicago, after all, would be where the notion of a “rainbow coalition” was first imagined and tried. And yet, with Puerto Ricans packing into the Division Street barrio, Mexicans flowing into the colonia of Pilsen, the black population becoming increasingly ghettoized, and whites fleeing the city, the odds seemed long for any kind of reform coalition politics capable of unifying different ethnoracial groups behind a sense of shared class injustice. Although working-class whites, blacks, Puerto Ricans, and Mexicans would all be scarred by the injuries of class, the racially inflected circumstances of Chicago in the 1950s and 1960s would ensure that the cause would be perceived or felt in racial rather than class terms: that race would be, as Stuart Hall has written, “the modality through which class [was] lived.”23

THE BIRMINGHAM OF THE NORTH

In late July 1963, the Chicago Daily News referred to the growing black mobilization for civil rights in Chicago as “a social revolution in our midst” and “a story without parallel in the history of our city.”24 Such pronouncements reflected, in part, events transpiring in the southern civil rights struggle. In particular, Birmingham was the word on the lips of blacks in Chicago and elsewhere that spring as the news media brought startling images of police turning attack dogs and high-pressure hoses on peacefully protesting men, women, and children, and Governor George Wallace declared he would “stand in the schoolhouse door” to prevent federally ordered integration at the University of Alabama. But Chicago’s civil rights leaders were quick to bring their fight into the discursive space opened up by the situation in Birmingham, challenging the notion long held by the Daley machine and some middle-class blacks that such problems were endemic to the South and did not apply to Chicago’s black community.

One could witness such processes in motion in early July, when Mayor Daley addressed NAACP delegates gathered in Chicago for their annual national convention. In classic fashion, Daley had arrived with a speech devoid of real substance, but when he proudly declared that there were “no ghettos in Chicago”—meaning that his administration did not view black neighborhoods in such negative terms—the head of the Illinois NAACP, Dr. Lucien Holman, blurted out, “We’ve had enough of this sort of foolishness.” “Everybody knows there are ghettos here,” he told a dumbfounded Daley, “and we’ve got more segregated schools than you’ve got in Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana combined.” Nor was this an isolated incident. A few days later, as Daley again addressed convention delegates and other black Chicagoans at the end of the July 4th “Emancipation Day” parade, his attempt to extend a friendly hand was once more met with derision. This time a crowd of about 150 protesters approached the platform shouting things like “Daley must go!” and “Down with ghettos!” Unable to complete his speech, Daley hurried off the stage, but his replacement, Reverend Joseph H. Jackson, minister of the South Side’s 15,000-member Olivet Baptist Church, fared no better. Jackson, a political ally of Daley and an outspoken critic of the civil rights movement, was met with a chorus of jeers and boos before he even uttered a word. The situation deteriorated so much that police had to escort him out of the area amidst shouts of “Kill him!” and “Uncle Tom must go!” While Daley later dismissed the whole affair with his quip that the protest must have been set up by Republicans, it was clear that something very real was afoot in black Chicago.25

By the fall of 1963 the many hundreds of miles stretching between Birmingham and Chicago could no longer keep the cities apart in the minds of many black Chicagoans. Reporters for the Chicago Defender missed few opportunities to highlight the link, especially in their coverage of the unraveling struggle being waged by local civil rights groups and ordinary parents about the deplorable conditions of black schools throughout the city. When school superintendent Benjamin Willis stubbornly clung to the ideal of colorblindness in resisting demands for student transfers to alleviate the problem of overcrowding, the Defender referred to him as Chicago’s own “Gov. Wallace standing in the doorway of an equal education for all Negro kids in the city.”26 Yet although the southern movement for civil rights lent African Americans in Chicago a sense of their own “historicity” as they organized to take on the status quo, such ideas were clearly secondary to the more immediate concerns—namely, the indignities and inequalities experienced by African American children in woefully inadequate schools.

Why the schools of black Chicago had fallen into such a sorry state by this time had a great deal to do with the city’s inability or unwillingness to effectively accommodate the rapidly increasing black population. Problems began to arise in the 1950s when Chicago’s overall population declined by almost 2 percent, but the number of African Americans living there increased by some 300,000, bringing the total to 812,637—nearly a quarter of the city’s 3.5 million inhabitants. The increasing densification of black neighborhoods and the fact that newly arriving black families during these years tended to be quite a bit younger than the white families they were replacing further strained existing school facilities in black Chicago. At the Gregory School in the Garfield Park area of the West Side, for example, the student body rose from 2,115 in 1959 to 4,194 in 1961.27 Citing the sanctity of the “neighborhood school” and the need to separate school policy decisions from city politics, Superintendent Willis responded to the problem of overcrowded black schools with an extensive double-shift program and trailer-like temporary classrooms—referred to by protesters as “Willis wagons.”

While Willis had dictated that the school district not keep any “record of race, color or creed of any student or employee,” several independent studies revealed the deep-rooted racial disparities that Willis’s colorblind ideals and band-aid policies were attempting to cover up. A 1962 Urban League study, moreover, found that class sizes were 25 percent larger in black schools and expenditures per pupil were 33 percent lower.28 Most African Americans, however, did not need such studies to confirm the injustices they confronted on a daily basis. Widespread disgust with the situation led first to the Chicago NAACP’s Operation Transfer campaign to have black parents register their children in white schools, and after that failed, to a series of parent-led sit-ins in several black neighborhoods, including Woodlawn, where the Alinskyite TWO (The Woodlawn Organization) organized school boycotts and demonstrations against the use of mobile classrooms at a local elementary school. Capitalizing on these uprisings from below, the Chicago Urban League, TWO, the Chicago NAACP, and a number of other newly formed community groups forged an umbrella civil rights organization, the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO), to carry on the fight.

By the summer of 1963 school protests had spread into several black communities on the South and West Sides, including the Englewood area, where parents joined activists from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in a spirited effort to halt the installation of mobile classrooms. Laying their bodies down at the construction site at 73rd and Lowe, the Englewood demonstrators provoked police into hauling them off, a spectacle that offered a first glimpse of the militant Chicago movement that was beginning to come together that summer. Renowned comedian and activist Dick Gregory was among the more than one hundred protesters arrested,29 some of whom broke with CORE’s nonviolent philosophy by kicking and stoning police. The militancy that day spawned a range of grassroots civil rights organizations seeking to carry on the fight for better schools, including the Parents Council for Integrated Schools and the Chicago Area Friends of SNCC (CAFSNCC), and those familiar with the fiery rhetoric from the charismatic Nation of Islam minister Malcolm X around this same time began to brace for some rough times ahead. So palpable was the anger of black protesters against the stonewalling tactics of Willis and the Daley machine that even after Chicagoans and the rest of the nation beheld what seemed like nonviolence’s finest hour—the spectacle of more than two hundred thousand gathered in Washington that August to hear Martin Luther King evoke his “dream” of racial integration—organizer Bayard Rustin told the Sun-Times that the march marked not the end but rather the beginning of a campaign of “intensified nonviolence” in Chicago.30

While somewhat nebulous, Rustin’s reference to intensified nonviolence was indicative of a tendency among civil rights leaders in this moment to stretch the concept of nonviolence to its breaking point—both rhetorically as well as through increasingly provocative protest actions. This was still some eight months prior to Malcolm X’s popularization of the call to armed struggle in his famous speech “The Ballot or the Bullet,” but many activists frustrated with the slow pace of progress were beginning to articulate tactics, ideas, and emotions that looked more and more like the ideological position Stokely Carmichael would describe as black power in June 1966. As historian Robert Self has argued, by paying too much attention to charismatic leaders like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, most scholars have treated black power as a “distinct, even fatal, break with the civil rights movement,” an interpretation that overlooks how much black power politics evolved gradually and logically out of the failure of integrationist approaches at the grassroots level.31

If by the hot summer of 1966 young African Americans shouting “black power” were rioting on the West Side and packing into halls to hear Stokely Carmichael speak, if they had begun to imagine complete control of their communities as the only form of political arrangement possible, that was because they had already run up against the unbending will of the machine. What was happening in 1966 was part of a longer story that had begun in 1963, just days after the March on Washington, when the Chicago Board of Education (CBOE) had raised the hopes of black Chicagoans by agreeing to an out-of-court settlement of a nearly two-year-old lawsuit filed by TWO charging racial segregation in the Chicago school system. In addition to agreeing to name a study group to come up with a racial head count and devise a plan to address racial inequalities, the CBOE had also adopted a rather symbolic transfer plan to permit a limited number of top students to switch to schools with honors programs when their own schools did not offer them. Yet even this cautious plan provoked virulent reactions in white neighborhoods around several of the schools on the transfer list, and Willis quickly caved in to this pressure, removing fifteen schools from the original list of twenty-four. When the CBOE ordered him to reinstate the schools, Willis refused, and then when faced with a court order to do so, he resigned. But in a surprising turn of events, the CBOE responded by voting not to accept his resignation, a move that received broad support among white residents on the city’s Southwest Side.

This outrage—not just the CBOE’s decision but also the emergence of Willis as a hero in the Bungalow Belt—provided the spark activists were looking for to consolidate the movement and take it to the citywide level. Two days later, Lawrence Landry, a University of Chicago graduate student and leader of CAFSNCC, called for a mass boycott of Chicago schools on October 22. On the day before the boycott, the CCCO published a list of thirteen demands in the Chicago Daily News, which included, among others, the removal of Willis as superintendent, the publication of a racial head count and inventory of classrooms, a “basic policy of integration of staff and students,” the recomposition of the board of education, the publication of pupil achievement levels on standardized tests, and the request by Mayor Daley for federal emergency funds for remedial programs in all schools where test scores were revealed to be subpar.32 Prior to the boycott, organizers were counting on the participation of between 30,000 and 75,000 students. When the day arrived, a stunning 225,000 answered the call to stay home from school.

To counter charges that students had merely taken the opportunity to skip school, boycott leaders set up “Freedom Schools” in churches and other neighborhood associations, where students sang freedom songs like “We Shall Overcome” and discussed civil rights issues. All students who attended Freedom Schools that day left with a Freedom Diploma. The lessons emphasized the contributions Africans Americans had made to the country’s history, compared the boycott to the Boston Tea Party, and encouraged students to think of themselves as “writing another chapter in the freedom story.” Landry had taken steps to make sure these classes were well attended, recruiting students to distribute thousands of informational leaflets in schools and churches throughout the city. The event was a smashing success. Chicago civil rights leaders had, in some sense, mobilized as many people as the March on Washington, and this success led to a series of similar boycotts in Boston, New York, Kansas City, Cleveland, Milwaukee, and other major cities. After several rounds of fruitless negotiations with school officials, the CCCO called for a second boycott on February 25, 1964, which, in comparison with the first boycott, was somewhat disappointing but nonetheless garnered the impressive participation of 175,000 students.

While generally appreciating the magnitude of what had been accomplished during these boycotts, most accounts view these events largely as failures. For one thing, the negotiations that followed the citywide boycotts failed to yield any substantial policy changes. For another, the coalitions of civil rights groups that staged these demonstrations were rife with tensions over strategy, and, in the course of the frustrating negotiations that followed them, the rifts between moderates and militants widened even further. This was particularly the case in Chicago, where within weeks after its triumphant first boycott, the CCCO was already in disarray. At the end of November it voted not to support a boycott of Loop stores called by CAFSNCC and then in mid-December Chicago CORE revealed that it would split into two chapters: a moderate West Side unit and a more militant South Side group. And yet, despite such divisions and despite the lack of tangible gains won by the anti-Willis demonstrations, a new style of organizing was in the making. An emerging class of homegrown militants had stepped onto the stage of the local civil rights struggle—people like Lawrence Landry, soon to be leader of the Chicago chapter of the ACT (not an acronym) organization, and Rose Simpson, head of the Parents Council for Integrated Schools. Defined as “militants” or “extremists” because of their anger over the intransigence of school and city officials and their belief in the need to counter it with more aggressive direct-action tactics, these new civil rights leaders also distinguished themselves by their vision of where to tap the potential lifeblood of the movement: in the streets of the poorest black neighborhoods in the city.

Activists like Landry who had taken on the machine frontally and had been mercilessly crushed, began to look to guerrilla tactics—albeit nonviolent ones if possible—to keep the struggle alive. And as with nearly all guerrilla campaigns, among the most eager recruits were the most precarious members of the community: the young and poor. In fact, black radical circles were discovering ghetto youths as the potential vanguard of black protest politics around this time. In an interview published in Monthly Review in May 1964, Malcolm X, whose autobiography would soon show how a young, small-time crook could grow into a heroic activist, declared that the “accent” in the struggle for black community control “is on youth . . . because the youth have less at stake in this corrupt system and therefore can look at it more objectively.”33 Several months later, Max Stanford, one of the founders of the radical Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), published an article in which he argued that as opposed to bourgeois black youths, working-class gang youths offered a potential rich source of oppositional energy. “Gangs are the most dynamic force in the black community,” he wrote. “Instead of fighting their brothers and sisters, they can be trained to fight ‘Charlie.’”34

Landry had met with both Malcolm X and Stanford in the spring of 1964, and he had come back to Chicago with a new idea about how to fight “Charlie.” While keeping up the pressure about the city’s refusal to adequately address the deplorable conditions of black schools, Landry now sought to capitalize on a form of injustice that was immediately familiar to ghetto youths: the almost daily experience of being frisked, manhandled, insulted, and sometimes arrested for trumped-up infractions in their own neighborhoods. By the summer of 1964, police brutality had come to serve as a perfect focal point for the more aggressive program Landry’s organization ACT was pursuing in Chicago for a number of reasons. For one thing, as groups like ACT and CORE sought to straddle the fence between a philosophy of nonviolence and increasingly popular calls for armed self-defense, direct-action protests against police brutality seemed to offer a way to strike back at the police without using violence. If being manhandled and hauled off by police did not exactly provide a triumphant sense of turning the tables on police power, at least it showed that demonstrators were not afraid to be subjected to such treatment. For another, focusing on the cops as aggressors turned the bodies and minds of youths towards the state and away from petty rivalries with other black gangs. Police brutality, especially when it involved a white officer and a black youth, was the ideal expression of the lack of control black residents possessed over their communities and their everyday lives—an issue that opened the way to a broader critique of race and state power that fit mobile classrooms and white beat cops into the same frame. Finally, this was a golden age for stirring up indignation about rough cops. Things were already bad in the late 1950s, when a federal investigation of the Chicago Police Department had led to the indictment of two West Side patrolmen for tying a black gang youth to a post and whipping him repeatedly with a belt, but the arrival of police chief Orlando Wilson in 1960 ushered in a new period of degenerating relations between the police and black communities.

An experienced police officer with a criminology degree from Berkeley, Wilson was brought in by Daley in the wake of a police corruption scandal to modernize and professionalize the Chicago Police Department. Wilson was supposed to produce immediate results to justify his ballooning budget, which led him to institute a controversial stop-and-frisk policy that had the logical effect of dramatically increasing confrontations between police and youths out on the streets in the early 1960s. Moreover, in 1961, Wilson issued the order that “gangs must be crushed” and established a Gang Intelligence Unit (GIU) to get the job done. Yet, perhaps the most important policy change Wilson ushered in was his effort to recruit black police officers. After just two years of his tenure, black officers in the Chicago Police Department had increased from 500 to 1,200, a change that was, on the surface, intended to improve relations between the CPD and black communities, but that actually may have helped facilitate the more aggressive policing tactics being employed by beat cops in black neighborhoods. Under Wilson’s rule, notorious black officers like James “Gloves” Davis were given free rein on the streets in the early 1960s. Davis, who years later would participate in the raid that resulted in the death of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, earned his nickname from his habit of wearing a black glove on his right hand when he administered beatings. In one particular incident, Davis was disciplined for pistol-whipping a youth, who was later awarded $4,800 in damages.

By the summer of 1965, Landry was rallying hundreds of youths to participate in demonstrations against police brutality in neighborhoods on the South and West Sides. In one protest in the West Garfield Park area, things got out of hand after a police officer had applied a chokehold and sprayed mace on an ACT demonstrator. Within just a few hours after the incident, some two thousand protesters carrying banners that read “Black People Must Control the Black Community” had assembled in front of the local police station to vent their anger by hurling rocks and bottles.35 Once again police brutality against a young man had proven the spark that could ignite the kind of outrage that moved people to act with their feet. That very same day, CCCO leader Albert Raby had led an anti-Willis march of barely one hundred demonstrators from Grant Park into the South Side. Three marchers were arrested for blocking traffic at 64th Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, but, even with news of an upcoming meeting between the CCCO and Martin Luther King in the air, this march failed to muster much energy. What had happened in Garfield Park, on the other hand, had drawn thousands into the streets and had planted the seeds of rebellion.

Almost a month later, on August 13, as the fires of an uprising in the Watts area of Los Angeles—the first in a wave of large-scale civil disorders across urban America—blazed for a third day, this West Side neighborhood revealed what ACT’s brand of direct-action tactics and consciousness-raising could yield. In a tragically poetic twist of fate, a speeding fire truck from a West Garfield Park fire station swerved out of control and knocked over a stop sign, which struck and killed a twenty-three-year-old African American woman. This all-white fire station in an all-black neighborhood had been the object of numerous ACT protests in the weeks leading up to the incident. The next night a youthful crowd of over three hundred battled with police, sparking off two days of rioting that caused some sixty injuries and over a hundred arrests. Occurring in the context of the devastating Watts riot, which began with a routine traffic stop gone awry and then continued with clashes between youth gangs and police, the struggle for community control between gangs and police took center stage in black Chicago. For leaders of the nonviolent movement, gangs would need to be reined in so as to allow direct-action protests to continue without the risk of urban disorders; for those who saw the need for more militant tactics, street gangs seemed like the perfect soldiers—if not leaders—in the battle for community control. Relegated to the role of community problems for many years, gangs appeared suddenly in the guises of social bandits and tragic victims of white oppression.

GANGBANGERS, MINISTERS, AND UNCLE TOMS

It was only a matter of time before gangs themselves began to recognize their part in the historic drama unfolding around them. In the wake of Chief Wilson’s mandate to crush gangs in 1961, gang youths would have had difficulty envisioning themselves as anything other than social misfits, but the script began to change during the rush of civil rights activism that hit Chicago in 1963 and 1964. Reflecting on their turn towards political activism in the twilight of the age of civil rights, members of the Vice Lords, the West Side’s most powerful gang during the mid-1960s, dated their awakening to the summer of 1964. The leaders of the Lords at that time—men in their twenties who had met in 1958 while serving sentences at the St. Charles reformatory (known on the streets as “Charlie Town”)—claimed that what motivated their decision to “do something constructive” was a concern about the “younger dudes” in the gang. “The fellas looked around and saw how many had been killed, hurt, or sent to jail,” they told their biographer, “and decided they didn’t want the younger fellas coming up to go through the things they did and get bruises and wounds from gangfighting.” To be sure, their idea of “doing something constructive” was by no means purely political or altruistic; influenced by increasingly fashionable black power ideas about the key role of black entrepreneurialism in uplifting African American communities, the Lords initially conceived of their turn away from gangbanging as an opportunity to “try to open some businesses.” However, Watts had a dramatic impact on their thinking. “When the riots started in Watts in 1965,” some Lords later claimed, “most people felt kind of proud because somebody could do something like that.”36

Controlling a territory that extended into neighborhoods falling under ACT’s influence in the summer of 1965, the Vice Lords began to see their role in the community in a somewhat different light. Although ACT’s guidance made the Vice Lords a precocious case in the story of gang politicization, this story had hardly begun for them. Before any kind of political expression of black solidarity could take hold among Chicago’s African American gangs, they had to relinquish, at least in part, the brutal struggle for supremacy and respect on the streets. Beginning in the spring of 1965, the city’s largest and most fearsome fighting gangs—the Vice Lords and their West Side rivals the Egyptian Cobras, and the South Side’s Blackstone Rangers and their enemies the Disciples—could think of little more than the imperative of expanding their ranks; their very survival depended on it. By the end of 1966, the Blackstone Rangers and Conservative Vice Lords were each rumored to command more than two thousand members, and their respective rivals—the Disciples and the Cobras—could likely count on the allegiances of between five hundred and one thousand members, which gave them just enough muscle to resist incorporation.

These gangs attained their stature through campaigns of forced recruitment, earning them the enmity of many in their communities. In areas like Woodlawn on the South Side and Lawndale on the West Side, where gangs were engaged in Darwinian fights to the finish, there were a good many youths who, whether through their own calculation or through pressure exerted by their parents, wanted little to do with this homicidal world. But gangs could not afford to lose unaffiliated youths to their rivals, and they could never be certain that a group of teens refusing to join them would not at some point run with their enemies. Under such circumstances bloodshed became commonplace in schoolyards and wherever else youths gathered, and Daley’s public relations team made sure to use every gang incident to claim that gangs rather than the mayor’s policies were to blame for the two main problems African Americans had been complaining about for years: defective schools and brutal cops. And although black parents generally understood that Daley was playing politics with his antigang offensive and that gangs were providing him with a convenient excuse to bring down the boot rather than investing more money, it was difficult for some to remain cool when their children’s lives appeared to be at risk. In one particularly heated community meeting between parents and police in Woodlawn after the killing of a local Boy Scout, for example, an enraged crowd cheered enthusiastically when someone shouted, “To heck with getting accused of police brutality, let’s use some force on these punks!”37

But to an increasing number of residents in certain black South and West Side neighborhoods around this time, gang members were also sons, nephews, cousins, and sometimes daughters and nieces. While the larger gangs around this time were overwhelmingly male, they usually encompassed female branches—the Vice Ladies, Cobraettes, and Rangerettes, to name some notable examples. And they almost always incorporated junior and sometimes “midget” divisions, a situation that was often disquieting for parents but that also indicated just how broadly representative of the surrounding community these organizations were. Moreover, the school protests and boycotts of previous years had revealed to numerous black Chicagoans that many of these gang youths had dropped out of school as a result of systemic discrimination; more and more residents thus began viewing the punishment they received from cops on the streets as further evidence of such problems. All these factors pushed gangs into the main currents of local politics in black Chicago, but even more important was the fact that the gospel of black power had created an enlightened and charismatic set of leaders who recognized larger goals than the mere accumulation of muscle on the streets and who viewed themselves as “organizing” or “building something” rather than just recruiting. These leaders, as in the case of the Vice Lords, tended to be older than most of the youths they were seeking to recruit—mentors, big brothers, sometimes even father figures—and they understood that rather than merely intimidate, their task was to organize, educate, and enlighten. They needed to convince youngsters to turn away from traditional conceptions of street respect and towards a mix of black power ideas related to racial unity, the struggle for civil rights, community control, and black entrepreneurialism.

A sign of the times was the adoption by both the Vice Lords and Blackstone Rangers of the term nation as part of their names—a potent symbol of the new meaning youths were attributing to membership in these gangs. “Their country is a Nation on no map,” poet Gwendolyn Brooks mused about the Blackstone Rangers.38 Yet nothing enhanced their credibility and status more than the close attention they were getting from top representatives of the SCLC, journalists, and even briefcase-carrying officials from Washington. Beginning in the summer of 1966, almost every major civil rights organization in Chicago wanted sit-downs with the Conservative Vice Lord and Blackstone Ranger Nations, and news of these meetings traveled fast around their neighborhoods. Already admired by teens and kids in the community for their swagger, this publicity made the leaders of these gangs into local heroes in the eyes of the younger generation. In Woodlawn, boys as young as eight and nine formed “Pee Wee Ranger” groups, and kids throughout the area could be heard shouting “Mighty, Mighty Blackstone!” in the playgrounds and schoolyards.39 In Lawndale, young boys crowded around the Vice Lords as they stood on street corners and donned oversized berets like the ones worn by some of the Vice Lord “chiefs,” as the gang’s leaders were called.40

However, if the leaders of the nation gangs were already beginning to look like homegrown celebrities by the spring of 1966, nothing gave them that aura of greatness more than their sudden intimacy with Martin Luther King himself. With the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 now on the books, the SCLC turned to the problem of de facto segregation in the North, and, as fate and circumstance would have it, Chicago was to become the critical battleground for the SCLC’s northern campaign. On some level, the choice was made by default after key black leaders in both Philadelphia and New York City had rebuked King while the CCCO under the guidance of Al Raby had been reaching out to him to help revive its flagging movement. Moreover, King had always been warmly received when he spoke in Chicago, and he felt—naively so, in hindsight—that Daley’s complete dominance over the city’s political machinery offered a unique opportunity. Daley’s press secretary Earl Bush later observed, “King thought that if Daley would go before a microphone and say, ‘Let there be no more discrimination,’ there wouldn’t be.”41

King’s advisers had tried to convince him that things were not going to be so easy. In one memorable meeting, according to an SCLC staffer, King kept running on about what he could do in Chicago while close advisor Bayard Rustin repeatedly interjected warnings like “You don’t know what you are talking about. You don’t know what Chicago is like. . . . You’re going to get wiped out.”42 To be sure, Chicago posed some new problems for King. Unlike southern cities, Chicago possessed its own black political leadership in the figures of black submachine boss William Dawson and a group of black aldermen who received just enough patronage to buy out their potential opposition to Daley’s brand of “plantation politics.” Nicknamed the “silent six” by critics who claimed they could only speak in city council meetings when Daley’s floor leader Thomas Keane allowed them to, this group consisted of William Campbell of the Twentieth Ward, Robert Miller of the Sixth Ward, William Harvey of the Second Ward, Ralph Metcalfe of the Third Ward, Claude Holman of the Fourth Ward, and Benjamin Lewis of the Twenty-Fourth Ward, until 1963, when he was found the night of his victory in the primary elections handcuffed to his desk with three bullet holes in his head and a cigarette burned down to his fingers. Lewis had apparently fallen out with both Daley and William Dawson over his piece of the ward pie; the moral of the story, one can be sure, was clear to the remaining “silent five.” Daley’s men in the so-called plantation wards had already been doing their very best to oppose the CCCO’s school protest movement, and they would surely be no friend to King. Nobody missed the fact that King’s integrationist “dreams” meant nightmares for black submachine politicians whose power depended upon the color lines keeping their constituents hemmed into their wards. And what was good for the black submachine was good for the machine itself.43 Moreover, while King’s southern campaign had received broad support from the black religious community, he could not expect the same in Chicago. By 1966 the machine’s longtime ally Reverend Joseph H. Jackson was coming under increasing fire for his “Uncle Tom” opposition to the Chicago civil rights struggle, but he still presided over a South Side congregation of some 15,000 members. And then there was Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad, who could claim thousands of black Muslim followers in Chicago and who, after promising his support to King, turned around and blasted him for selling blacks out to white America.

For King, all of these issues were secondary to what he considered to be the two major challenges ahead: getting average Chicagoans into the streets and keeping things calm. And he understood that Chicago’s big gangs could make or break both of these objectives. Summer was approaching and after the riotous events in Watts and the near-riot in the Garfield Park area during the previous summer, the leaders of the Chicago Freedom Movement (CFM)—the name given to the new alliance between the SCLC and CCCO—feared that the outbreak of rioting might jeopardize their nonviolent campaign. Gangs, some believed, could not only be persuaded to refrain from rioting, but they might also be convinced to help keep the cool on their respective turfs. Moreover, the sheer numbers of youths loyal to these organizations made them useful to King’s and Raby’s objective of amassing an army of nonviolent protesters for a series of marches into Chicago’s lily-white Southwest Side—even if including them came with the additional challenge of keeping them nonviolent.

Hence, in January 1966, just days after King’s family had settled into their dilapidated slum apartment at 1550 South Hamlin Avenue in the West Side Lawndale neighborhood, King was already receiving a group of neighborhood kids who also happened to be Vice Lords. By spring, the campaign to win the hearts of the city’s gangs to the nonviolent civil rights movement was in full swing. On May 9, key SCLC organizers James Bevel and Jesse Jackson held a “leadership conference” for over 250 Blackstone Rangers down in the Kenwood area, during which they led discussions on nonviolence after watching footage of rioting in Watts. Then, in the first week in June, the Chicago Freedom Movement’s gang point men took their show to the West Side, where they organized meetings with the Vice Lords and Cobras.44 After sending several members of the Vice Lords and Rangers on a trip to Mississippi to witness the southern civil rights campaign firsthand, the SCLC hosted over fifty gang leaders at the First Annual Gangs Convention, in the Sheraton Hotel downtown on the eve of the CFM’s first big civil rights rally.45

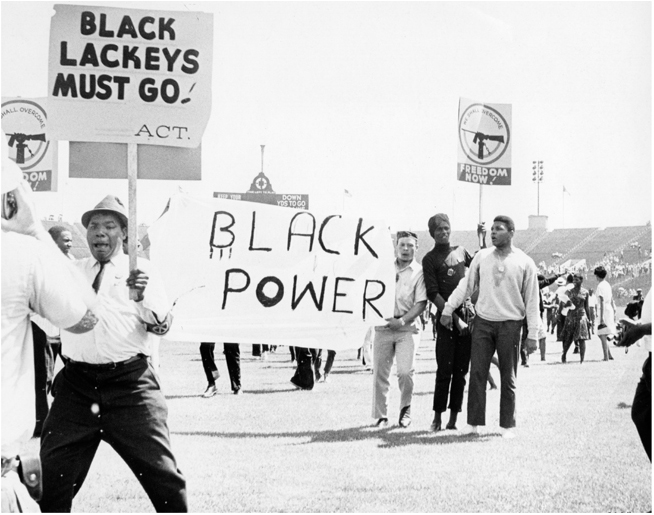

The next day, however, when the Chicago Freedom Movement gathered its army at Soldier Field for a show of unity and strength, serious tensions between Chicago’s black gangs and the CFM revealed themselves for all to see. Some two hundred Vice Lords, Blackstone Rangers, and Disciples occupied the center of the field, several waving a large white banner emblazoned with the words “Black Power”—a phrase that King openly detested. Then a scuffle ensued between some of the gang members and a few newsmen snapping photos, and several minutes later, without warning, the whole group abruptly marched out of the stadium. Afterwards it was learned that a gang member had apparently heard a high-ranking SCLC official insult the gangs, remarking something to the effect that they did not need them there because they would only cause trouble. Upon hearing about the affront, the leaders of the gangs gathered and decided they would all depart in unison on signal.46 With CFM leaders predicting a crowd of 100,000, the turnout, estimated to be some 30,000, was already being spoken of as a disappointment; the gaping hole in the center of the crowd where the gangs used to be seemed to show why. For those close to the gang organizing effort, however, this incident came as no surprise. The nonviolent style of struggle had met with skepticism and outright criticism on the part of gang members from the beginning. On one occasion the Rangers ridiculed the idea of singing freedom songs, causing the physically imposing SCLC organizer James Orange to shout back, “You think you’re too bad to sing? Well I’m badder than all of you, so we’re going to sing.”47 Perhaps most importantly, gang members could not stomach the idea of putting their necks on the line for nonviolent demonstrations whose impact was dubious at best. From the start, mainstream civil rights leaders asked them to be prepared to go to jail and take beatings for the cause, something that in the minds of many gang members offered little reward.48 Longtime Vice Lord, Cupid, one of those who marched out of the Soldier Field rally, later explained: “I can’t sing no brick off my motherfuckin’ head. I just can’t overcome. If a motherfucker hit you, knock that motherfucker down.”49

FIGURE 11. Martin Luther King at Soldier Field, July 10, 1966. Chicago Urban League Records, CULR_04_0194_2204_4, University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

The prevalence of such thinking among black gang members was revealed more strikingly just two days after the rally, when a massive rebellion shook the West Side. The explosion occurred after police responding to the theft of some ice creams from a broken-down truck at Throop and Roosevelt on the Near West Side manhandled a group of kids seeking refuge from a heat wave in the cool water of an open fire hydrant. There were several public swimming pools in the vicinity, but all were off limits to blacks. Despite the efforts of community leaders from the local West Side Organization (WSO) to calm the angry crowd that began to form around the scene, things got out of control. That same night, Martin Luther King addressed a mass meeting at the nearby Shiloh Baptist Church, issuing a plea for nonviolence, but youthful members of the audience abruptly stormed back out onto the streets amidst shouts of “Black Power!” The next evening, a meeting between gang members, police officials, and civil rights leaders yielded similar results. When the SCLC’s Andrew Young took the podium to make an appeal for nonviolence, a teenager in the audience immediately interrupted him, inviting his “black brothers . . . out on the street.”50 By the time a battalion of National Guardsmen had managed to restore order, the West Side riot had caused two deaths, over eighty injuries, and over $2 million in property damage. Mayor Daley exploited the situation by accusing CFM leaders of inciting violence among gangs, pointing to the SCLC’s screening of films about Watts as proof. “Who makes a Molotov cocktail?” he asked at a press conference.” “Someone has to train the youngsters.” Such ludicrous charges placed the CFM on the defensive, but what was perhaps even more disconcerting about the riot for civil rights leaders was that it had broken out spontaneously among youths unaffiliated with any of the city’s notorious gangs. It seemed to reveal a general mood, not a plan. King and the SCLC, it appeared, were not reaching the younger generation of black Chicago.

FIGURE 12. Black power militants at Soldier Field, July 10, 1966. Photo by Ted Bell. Chicago Urban League Records, CULR_04_0092_0966_001, University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

Nonetheless, despite this falling out between the CFM and Chicago’s elite gangs, when the time came to march into some of the city’s most racist strongholds, at least some gang members were still willing to answer the call. The plan called for a series of “open-housing marches” into the Gage Park–Chicago Lawn–Marquette Park area of the Southwest Side, where, according to the 1960 census, only seven out of more than 100,000 residents were not white. The marches into Chicago Lawn and Gage Park got off to a bad start when angry white residents hurled rocks, bottles, and explosives at the hundreds of marchers and shouted “White Power!” and “Burn them like Jews!”51 The SCLC-CCCO thus mustered up a larger group for the next big march through Marquette Park and Chicago Lawn on August 5. Among the group of some 1,400 gathered at the New Friendship Baptist Church before the march, according to a police operative from the Gang Intelligence Unit (GIU), more than 200 were members from a range of South and West Side gangs. Having sworn to observe the rules of nonviolent protest, they were there to serve as marshals for the march.52 A number of Blackstone Rangers participating in the demonstration wore baseball gloves to catch bottles, bricks, and stones.53 Despite their best efforts, however, they were no match for the thousands of whites who showered them with hate and debris, even fiercely battling with police to get at the demonstrators. Shouts of “Kill those niggers!” and “We want Martin Luther Coon” filled the air. A rock struck Martin Luther King in the head, opening a bloody gash, and he was far from the only casualty. So intense was the frenzied hatred directed at the marchers that King would tell a reporter from the New York Times that “the people of Mississippi ought to come to Chicago to learn how to hate.”54 Faced with this barrage of violence, much of it perpetrated by kids and young men of about their age, the gang members kept their word. As King recalled proudly after the march, “I remember walking with the Blackstone Rangers while bottles were flying from the sidelines, and I saw their noses being broken and blood flowing from their wounds; and I saw them continue and not retaliate, not one of them, with violence.”55

In spite of this symbolic triumph, that bloody day in Marquette Park destroyed what little was left of the alliance between Chicago’s gangs and the nonviolent movement. South Side gangs like the Rangers and Disciples had participated in the march because King had personally managed to patch up relations between the gangs and the CFM in the aftermath of the civil rights rally and West Side riot; on the other hand, relations were still tenuous with West Side gangs, which were noticeably absent from the event. The gangs that did come no doubt recognized the historic opportunity they had been handed. These gang youths had been marginalized in their communities, knowing only the glory of a world disparaged by many around them; the attention King and other civil rights leaders bestowed upon them inserted them into the flow of history itself. Ironically, however, this same consciousness empowered the gangs to the extent that they no longer needed the CFM, making them wary of being submerged in a movement directed by people they considered to be outsiders.

Moreover, the CFM’s open-housing campaign was out of step with the main concerns of working-class black communities. No doubt touched by the explosion of black power notions of community control around this time, many young African Americans on the West Side could not understand the idea of sticking their necks out to march into a white, middle-class neighborhood where they would not want to live even if they could.56 The Vice Lords, for example, seemed more receptive to organizations addressing immediate problems in their own neighborhood. For example, when the East Garfield Park Community Organization newsletter reported on July 25, 1966 that Vice Lord leader Duck (James) Harris had told the East Garfield Union to End Slums (EGUES) that “the Vice Lords have joined the movement to help organize the people,” the “people” they were referring were their West Side neighbors.57 While Martin Luther King had been instrumental in the founding of EGUES, the success of this organization hinged on its local focus. When EGUES brought slumlords to the negotiating table that summer, people were given the kind of direct taste of empowerment that was lacking in the CFM’s nonviolent movement. Moreover, the SCLC was surely somewhat out of touch with the reality of many gang members. This much was clear early in the campaign, when, in an effort to spark the interest of the Rangers and Disciples, an SCLC representative had told a room full of high school dropouts that they would soon be able to attend classes at the prestigious Northwestern University.58

Any citywide movement would have run up against similar problems: these street gangs had developed within a logic that placed a premium on autonomy and the control of turf, and they followed a code by which one never allowed a physical attack to go unchallenged. Black power ideas of community control and self-defense were thus a much better fit with the consciousness and experience of gang youths. And as the SCLC-CCCO was leading hundreds of marchers into ambushes on the white Southwest Side, others in black Chicago were rallying around black power. At an ACT rally attended by West Side gang members on July 31, speakers referred to the beatings of civil rights leaders in Gage Park that day, advocating the use of violence to deal with such acts by “Whitey.”59 Just four days earlier, Stokely Carmichael, SNCC’s field secretary, had spoken at a “black power rally,” where he had urged blacks to regain control of their communities, even if it meant using violent means to do so. Such ideas filtered down into the ghetto through the words and deeds of a charismatic group of gang elites, whose reinterpretation of black power became the gospel of the streets.