SIX

Violence in the Global City

1968

To many, the roughly two-year period that began with the toxic mob violence surrounding the open-housing marches and ended with the apocalyptic chaos that reigned in the streets outside the Democratic National Convention of 1968 represented the darkest of moments in Chicago’s history. This was a time when American Nazi Party leader George Lincoln Rockwell, regaled in black boots and swastikas, drew admiring crowds of thousands of angry white youths in Marquette Park, when black youths on the West Side took to the streets in a riotous outburst of destruction while Mayor Daley told his police force to “shoot to kill . . . arsonists,” and when Chicago cops savagely beat antiwar demonstrators during the convention, the air thick with choking teargas, nightsticks cracking bones, shouting “kill, kill, kill!” It was a time when political organizations with names like Black Panthers and Young Lords patrolled the streets in color-coded berets and military attire, when ordinary African Americans wore dashikis and spoke in a stylized language about “brothers” and “sisters,” and when college students kept their hair long and greasy, dressed like factory workers or flower children, and swore they really believed the revolution was imminent. It was a time when politics was in the streets, out there for all to see. Many cities had some of this, but Chicago seemed to have it all, which, was, in part, why in 1968 Norman Mailer called it “perhaps . . . the last of the great American cities.” In one of the more enigmatic passages of his masterful reportage for Harper’s on the tumultuous events surrounding the Democratic National Convention in Chicago that year, Mailer mused that “only a great city provides honest spectacle, for that is the salvation of the schizophrenic soul.”1

While what Mailer meant by “honest spectacle” is a matter of interpretation, he may have been contrasting Chicago’s gritty, kick-in-the-face feel—captured by the blood and entrails on the floors of its packinghouses, its beefy mayor, and the very visceral beatings its police force doled out to those who dared oppose him—to the kind of dishonest spectacle being disseminated by the advertising industry that, according to Guy Debord’s 1967 work The Society of the Spectacle, was distancing people from both “authentic” experience as well as from each other. It was not difficult to see traces of Debord’s ideas on a range of student groups in the United States, who, after years of seemingly futile marches and administration-building occupations against the war in Vietnam, began to look for new methods of combat that would change the traditional endgame of student demonstrators being beaten and hauled away by the authorities. The Youth International Party (commonly referred to as the “Yippies”) was the most high profile group to use alternative forms of association and expression—high-concept pranks and political theater in the streets—to bring about transformations in consciousness, but the whole countercultural student movement was moving in this direction. This was not a movement that had a great deal to do with Chicago, whose campuses never mustered very much newsworthy activism during the peak years of student protest. The national bases of the student movement and of the counterculture were San Francisco, Berkeley, New York City, and a number of midwestern college towns like Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Madison, Wisconsin. A courageous group of politicos belonging to the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) had launched the ambitious Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP) in 1964 to organize working-class whites in Chicago’s tough Uptown neighborhood on the North Side, but the initiative had largely failed to accomplish anything lasting. The “city of the big shoulders” was resistant to the idealism and countercultural ethos of the student movement. The only university of any national prestige within the city limits had been building walls around itself for years, and the city’s tradition of radicalism was far too rooted in a jaded, Old Left, workerist vision of the world to embrace the faddish existential critique circulating around the New Left in the late 1960s. And then there was the racial divide, which, as black power consciousness surged throughout the ghetto, was becoming wider by the minute. With good reason the white middle-class SDS cadres that started Chicago’s ERAP chose to knock on doors in largely white Uptown rather than in the heart of the West Side ghetto.

During the high times of student activism and countercultural expression in the United States, Chicago’s hippie scene thus remained undeniably sedate, confined to a relatively small area around Wells Street in the Near North Side’s Old Town neighborhood, where white flight and undesirable commercial activity had made the area affordable for self-styled bohemian types. Here one could find a handful of head shops, record stores, coffee shops, and music clubs. The national chain Crate and Barrel got its start in this neighborhood around this time, finding an eager clientele of the young and disenchanted in need of affordable home furnishings imported from Asia, India, and Europe to help them escape the painful conformity of American consumer culture. The community had its own newspaper, The Chicago Seed, and with the national headquarters of SDS just down in the Loop, there was enough activity to keep things interesting. Yet Chicago was clearly a “second city” for hipsters; considering the city’s size and its role as the only real refuge for alienated youths and other social misfits looking to escape the suffocating conformity of the suburbs and small towns of Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin, it is surprising how few folk artists, writers, and activists hailing from Chicago made it on to the national stage. Chicago’s Old Town hippie scene was swallowed into the mainstream before it produced anything to distinguish it. “The aimless young and suburbanites swarm all over this area on weekends,” Studs Terkel mused in his 1967 book Division Street America. “It has the spirit of a twentieth century carnival, in which commerce overwhelms joy.”2 So it is ironic that beginning in the spring of 1968, Chicago became the destination for a generation of young radicals looking to vent their anger against the Democratic Party’s stubborn support of the escalating war in Vietnam, and it is even more ironic that beginning in the fall of 1968, when the show was over, it became the place that Americans would associate with the countercultural excesses and confrontational street politics of the antiwar movement and of the New Left in general.

Chicago was an unwilling participant in the denouement of the student movement, so unwilling that its very reluctance became a crucial element in the plot—a primary reason why the antiwar protest around the Democratic National Convention would be interpreted across the nation as the last gasp of a dying movement. One can argue with good reason that the poor turnout of protesters doomed the Chicago campaign of 1968. The National Mobilization Committee to End the War (MOBE), under the leadership of movement veterans Rennie Davis and Dave Dellinger, had begun organizing for the convention more than ten months in advance, but they made a fatal error of expecting crowds in the hundreds of thousands, numbers that would have overwhelmed the capacity of the forces of order to contain them. Their optimism was based largely on the idea that students from all over the country would pour into Chicago for the event, but they did not come, in part, because of all the rumors about the dangerous tactics being plotted on both sides of the barricades and, in part, because of the multiple fractures dividing the New Left. Their hopes for a momentous show of opposition were also based on the expectation that a number of local protest organizations in black, brown, and white Chicago would participate, as well as students from the city’s colleges and high schools. Regardless of how many itinerant hippies and politicos from out of state made it to town, a city of Chicago’s size could have very well gone it alone.

But when nominating night finally arrived and the movement got a chance to see itself massed in Grant Park awaiting orders to march (in which direction was a matter of debate), it was clear that the movement culture that the Yippies and MOBE had attempted to put together had failed to take root in the city of Chicago. In the days leading up to the convention the Yippies had planned a series of stunts and events to try to attract fellow travelers. They had arrived with a two-hundred-pound pig named Pigassus, whom they declared their Democratic candidate for president, they had circulated ribald rumors about dosing the city’s water supply with psychedelic drugs and recruiting an elite corps of handsome Yippies to seduce the wives and daughters of delegates, and they had planned a “Festival of Life” in Lincoln Park featuring the hip Detroit rock band MC5. Yet, even if the media found the Yippies good for a few laughs and, more importantly, for selling some newspapers, the whole campaign failed to spark much interest in the city. Almost one year later to the day, Woodstock would attract some five hundred thousand participants; most estimates of the crowd at the Festival of Life top out at five thousand. To be sure, many probably stayed away from the Sunday afternoon event because of the wild happenings of the previous nights, when the police had used teargas and brutal tactics to clear Lincoln Park of the thousands intending to use it as a campground. Organizers had been requesting that the city waive its park curfew rules in order to give protesters a place to sleep, but the city had equivocated and ultimately rejected the demand. The request of the Festival of Life organizers to drive a flatbed truck into Lincoln Park to provide a stage for MC5 had also been refused, so only a few hundred in the audience could actually see the band, a situation that led to pushing and flaring tempers. When the organizers attempted to bring the truck in anyway and were stopped by the police, things got out of hand once again, with police roughing up protesters and the concert being called off. That night the police again used teargas and nightsticks to clear the park, with protesters retreating to the surrounding streets to wreak havoc.3

Many of the more than ten thousand demonstrators who made it to the afternoon rally in Grant Park before the big night of the convention, when the Democratic Party was going to name Hubert Humphrey as its nominee, were ex-combatants in this war of attrition. The crowd gathered here for what would turn out to be the final act of the drama included the more clean-cut supporters of the antiwar candidacy of Minnesota senator Eugene McCarthy; the scraggly, sleep-deprived, nervy demonstrators from the Lincoln Park battles; and a host of high-profile intellectuals such as Norman Mailer, William Burroughs, and Jean Genet. Organizers had been warned that they would not be allowed to get anywhere near the convention proceedings at the International Amphitheater, but police intelligence had learned they were going to try to make the four-mile walk anyway. Bolstered by some seven thousand National Guard troops outfitted with bayonet-tipped rifles, teargas masks, and jeeps mounted with barbed wire, the Chicago police once again moved into the crowd with astonishing speed and indiscriminate violence.

What happened next inarguably played a role in changing the course of American political history—if not in the way one might have expected at the time. After the police had dispersed the crowd in Grant Park, a mass of marchers re-formed at the intersection of Balbo and Michigan Avenue, where the media had set up fixed cameras to cover the delegates leaving their rooms at the Conrad Hilton, and that was when things got utterly and spectacularly ugly. A battalion of blue-helmeted policemen rushed the crowd, and, with no attempt whatsoever to distinguish marchers from onlookers, began smashing heads, legs, and arms. Piecing together a number of eyewitness accounts, historian David Farber describes the scene:

A police lieutenant sprayed Mace indiscriminately at a crowd watching the street battle. Policemen pushed a small group of bystanders and peaceful protesters through a large plate glass window and then attacked the bleeding and dazed victims as they lay among the glass shards. Policemen on three-wheeled motorcycles, one of them screaming, “Wahoo!” ran people over.4

In the midst of it all, people started spontaneously chanting, “The whole world is watching, the whole world is watching.” The delegates, however, did not have to wait the ninety minutes it took for the networks to get the images to television screens. Looking down from his fourth floor room at the Hilton, Senator George McGovern reportedly said, “Do you see what those sons of bitches are doing to those kids down there?” Hours later, on the floor of the amphitheater, Connecticut senator Abraham Ribicoff—a man not known for his oratorical flair—used his nominating speech for McGovern to tell the convention, “With George McGovern we wouldn’t have Gestapo tactics on the streets of Chicago,” a comment that provoked Daley and his entourage to jump up and shout a litany of barroom obscenities whose precise nature is still a matter of debate. Some close by heard the mayor shout, “Fuck you, you Jew-son-of-a-bitch!”—a phrase that lip-readers not employed by the city of Chicago would corroborate from the video footage of the outburst. Supporters of the mayor would later claim he had called Ribicoff a “faker,” and during the convention’s final session the next day, he made sure to pack the amphitheater with machine diehards who were under orders to engage in rousing choruses of “We love Daley!” Yet, regardless of what the mayor had said and regardless of the show of adoration he had orchestrated, Daley appeared to be in trouble for the second time in five months.

Chicago had been awarded the convention, in part, because it had avoided civil unrest in the summer of 1967, when ghetto riots raged in Detroit and New Haven, and Daley was seen as a man who knew how to keep a lid on things. Even before the summer, Daley’s tough talk on law and order, combined with the growing realization among working-class whites that the open-housing summit had hardly been the catastrophe that hardcore anti-integrationists had feared, had enabled Daley to regain the support he had lost in the Bungalow Belt. The result was a staggering landslide election victory that saw the Boss capturing 73 percent of the overall vote and winning all fifty wards. Even after breaking the promises he had made to Martin Luther King at the summit, Daley had run strongly in the black wards, taking nearly 84 percent of the vote. The mayor seemed as invincible as ever, and many within Chicago’s homegrown left began half-seriously pondering guerrilla warfare. But then in April, he seemed to have gone much too far in his reaction to widespread rioting on the West Side following King’s assassination in Memphis. After Daley had publicly excoriated new police chief James Conlisk for not following his orders to “shoot to kill any arsonist . . . and to maim or cripple anyone looting,” even some of the machine’s loyal black aldermen spoke up against him. After the damage and destruction of the West Side riot—hundreds of arrests, eleven deaths, thousands homeless, and a twenty-eight-block stretch of West Madison Street burned—it was no longer possible to claim that Daley had managed to appease black Chicago with all the money he had garnered from the federal government’s antipoverty programs.

The riot, which broke out after mobs of West Side youths went from high school to high school, disrupting classes and urging students out into the streets, revealed the extent to which the West Side’s working-class black population remained marginalized in Daley’s Chicago despite the best intentions of the federal government’s antipoverty programs. As was the case for the federal urban renewal initiatives of the 1950s, the Daley machine had hijacked Chicago’s Community Action Program, which had expressly sought to bypass the machine by placing power directly into the hands of neighborhood people. Black communities would have their representatives—this, after all, was the law—but Daley made sure that their representatives would also be his representatives and that the black man running the whole program, Deton Brooks, was his black man. By the spring of 1967, the situation prompted a Senate subcommittee to look into allegations that Daley was not adhering to the spirit of “maximum feasible participation” required by the law. But Senator Robert Kennedy, who needed Daley’s support for his presidential run (which would end nearly three weeks later with Kennedy’s assassination), defended the mayor, and when riots ripped through New Haven and Detroit, it was hard to find a liberal in Washington who would support the idea of empowering black ghetto communities.

By the summer of 1967, newspapers across the country were painting every urban disorder and inflammatory black power declaration as evidence of the failure of Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty and of liberalism in general, and few pursued this polemic more zealously than Chicago’s own Tribune. If, as longtime Chicago columnist Mike Royko has argued, Daley was a “white backlash” mayor years before anyone was even using the term, one could extend this observation to the city that had been so strongly supporting him since his election in 1955.5 Not only was Chicago—despite its Democratic stripes—in the vanguard of the white backlash that decisively captured the American political center with the election of Richard Nixon to the presidency in 1968, but the city itself had been the main stage upon which the dramas of a surging reactionary populism played out before the eyes of the nation. It was in Chicago that the black struggle for equality ran into the wall of white homeowners’ rights during the open-housing marches; it was in Chicago that one of the cornerstones of Great Society liberalism—the idea of redistributing power and resources downward to neighborhood people—was shattered by a Senate subcommittee investigating a gang called the Blackstone Rangers for embezzling federal funds; it was in Chicago that a big-city mayor told his police force to shoot at young African Americans for stealing transistor radios and to, in effect, summarily execute black arson suspects; and it was in Chicago that battalions of policemen bloodied and teargassed college kids, hippies, members of the media, and innocent bystanders in front of the whole world. And finally, it was in Chicago that most of the mainstream media and much of the population cheered the mayor’s campaign of repression every step of the way as liberals throughout the nation were decrying it.

What was transpiring in Chicago defined the “backlash” structure of feeling and reactionary politics that had taken hold of the country’s political culture by the middle of 1967—and has not relinquished its hold ever since. Students of modern American conservatism usually recognize Richard Nixon as one of the key architects of this approach. Campaigning and taking office in a media landscape inhabited by gun-toting black militants, flag-burning student radicals, bra-burning feminists, and liberated gays and drag queens, Nixon claimed to be representing the “silent majority” of law-abiding, hard-working, patriotic Americans whose voices had been silenced by the clamor of extremists in the streets. And yet, if Nixon was the one who actually uttered the clever phrases, he was taking his cues from Richard J. Daley, who, unlike Nixon, was a pure product of the backlash. Although some scholars have highlighted the importance of hard-core segregationist George Wallace’s surprising northern success in the 1968 presidential primaries, which, according to some, pushed Nixon and the Republican Party towards a “southern strategy” that instrumentalized racial fears in order to lock up the South forever, it was Daley—a northern Democrat no less—who revealed the prescription for backlash politics moving forward.6 It was Daley who showed the nation that most people were bothered more by rioting blacks than by mayors who ordered the use of lethal force to stop them, and that most people identified less with antiwar protesters than with the police officers beating them with nightsticks.7 Facing reporters after the convention, the straight-talking mayor defended the actions of his police force by referring to the nasty insults that antiwar protesters hurled at the police and repeatedly asking, “What would you do?” When anyone mentioned antiwar protesters, he would ask, “What programs do they have?” and “What do they want?” Apparently these were the same questions being posed by Americans throughout the nation. Thus, it was of little consequence that Daley was being slammed in the New York Times, Washington Post, and many other major northern media outlets and that a federally appointed investigative commission had blamed the police for the violence at the convention and condemned the mayor for failing to reprimand them for it. By the fall of 1969, a Newsweek poll revealed that 84 percent of white Americans felt that college demonstrators were being treated “too leniently” and that 85 percent felt the same way about black militants.8 Daley had played a critical role in making the backlash, and now it was making him a living legend.

BESIEGED BY LAW AND ORDER

Chicago was thus a backlash city years before anything looking like a backlash had spread across the metropolitan United States, and as such, it was an ill-fated choice for the site of the antiwar movement’s last-ditch battle. The massive scale of Chicago’s black migration in the 1940s and 1950s, which multiplied the color lines throughout the city as well as the border wars that came with them, certainly played an important role in producing its precocious backlash sensibilities. Such circumstances shaped a siege mentality long before the urban disorders of the mid-1960s had normalized such thinking in most major U.S. cities, and this siege mentality created an insatiable appetite for law enforcement and an aversion to the intervention of city government in any other form, especially when it involved constructing housing for the poor. Even the illustrious University of Chicago, which, with so many liberal luminaries on its faculty, could have provided a powerful bulwark against backlash sensibilities, was seized by this siege mentality. This had not always been the case. The Chicago School sociologists were great leaders in the intellectual struggle against racial theories of black and immigrant poverty, and their students were not infrequently arrested while defending blacks against white mobs in the 1940s and 1950s. Saul Alinsky had enrolled here to study archaeology, but after spending four years in UC classrooms had set out to work as a community organizer. But by the time he returned to Hyde Park in 1960 to defend the people of neighboring Woodlawn, his alma mater had switched sides, aligning its interests with the machine and thus becoming his adversary in his fight for social and racial justice.

UC chancellor Lawrence Kimpton, the man who had helped broker the real estate coup that was going to cleanse the area around the university of thousands of working-class black families, it is worth mentioning, was the same man who in 1958 had intervened to forbid the university’s literary magazine, the Chicago Review, from publishing the works of Beat writers Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs. Kimpton was thus clearly not keen on allowing the University of Chicago to reach out into the community and become a refuge from the backlash, a role that universities at times played in the late 1950s and 1960s. But more important to Chicago becoming a full-fledged backlash city so early was the enormous power of the Daley machine in co-opting, blackmailing, infiltrating, and, when all else failed, using brute force to stifle any potential opposition to itself and its friends.

In fact, such practices predated Daley’s rule. Starting in the 1930s, Chicago had become, according to historian Frank Donner, “the national capital of police repression,” a reputation that went far beyond the Memorial Day Massacre of 1937.9 The Chicago Police Department’s “Red Squad” was rooting out Communists and using intimidation to subvert the labor movement throughout the 1930s and 1940s. The success of these efforts was revealed by the quiescence of its unions during World War II, while its industrial neighbor to the east, Detroit, was a hotbed of labor agitation. But the Red Squad’s purview did not stop at the workplace; it extended into any organization engaged in political activities. “Issues dealing with labor, wages, working hours, strikes, peace, housing, education, social welfare, race, religion, disarmament, and anti-militarization” were all named as sources of “subversive activities” by the Chicago Red Squad’s Lieutenant Frank J. Heimoski in a 1963 speech to a national conference of police intelligence officers: in other words, in the paranoid minds of Red Squad operatives, the very idea of politics itself, when practiced by any person or group not directly affiliated with the Cook County Democratic Party, was subversive. “Our job,” Heimoski claimed, “is to detect these elements and their contemplated activity and alert proper authorities.”10

The extent to which the Chicago Police Department’s Red Squad stunted the development of a political and cultural infrastructure for the left in Chicago is one of the great untold stories of American history.11 In 1960, the CPD claimed it had intelligence files on 117,000 local individuals and some 14,000 organizations nationwide, most of which were destroyed after the ACLU and a coalition of local civic and religious groups called the Alliance to End Repression successfully sued it for improper police intelligence activities. The files that survived the shredder, however, were more than adequate to show how aggressively the Red Squad had, through illegal surveillance and infiltration, intimidated, harassed, and effectively neutralized individuals and organizations who dared to think outside the box.

Police repression was thus a deeply established tradition in Chicago in the decades leading up to the great progressive challenges of the mid-1960s. It was as emblematic of the city as the ivy-covered red brick walls at Wrigley Field. But the technologies and methods of repression reached a whole other level during the turbulent years of the 1960s. To keep up with the rapid proliferation of political organizations and individuals with multiple and shifting affiliations, the Red Squad developed a sophisticated cross-referencing system, and to counter the development of threats to the machine’s power in black, Puerto Rican, and Mexican neighborhoods, it deployed an army of undercover operatives to engage not only in intelligence activities but also in tactics of subversion. The Red Squad left no stone unturned. There were even files on the Old Town School of Folk Music, and no small number of them either. But the organizations and activists that drew the most attention were those attempting to build bridges across different racial and ethnic communities, and it is here one can detect a mayoral agenda at work, even if the purge of documents would later cover most of its traces.

The Daley machine had expertly maintained its power by the logic of divide and rule and by fostering a political culture in which the substance of politics consisted of nonideological, neighborhood-level struggles for shares of the patronage pie. Anything that disrupted this status quo set off alarms in City Hall. In the months leading up to the convention, for example, the buzz in the Red Squad revolved around the potential for a concerted mobilization of white middle-class students and ghetto blacks affiliated with supergangs and black power groups—a potential demonstration of cross-class and cross-racial solidarity that would have created a public relations problem for Mayor Daley. Thus, this was not only a matter of police intelligence but also one of special operations. Chicago cops blanketed the South and West Sides, rounding up gang leaders and warning them that they would pay a heavy price if they were seen anywhere near the convention, while undercover police operatives sought to stir up racial tensions among both black power and student groups.

In fact, the Red Squad was a big beneficiary of the FBI’s COINTELPRO (Counterintelligence Program), a holdover from the rabid anticommunism of the 1950s, which funneled manpower and resources to a number of major American cities to help them “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” organizations and individuals viewed as posing threats to national security and social order. FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover believed, much like Mayor Daley, that black power organizations were worthy of special attention, and nothing caused more consternation at FBI headquarters than when these organizations began to make alliances and develop their bases.

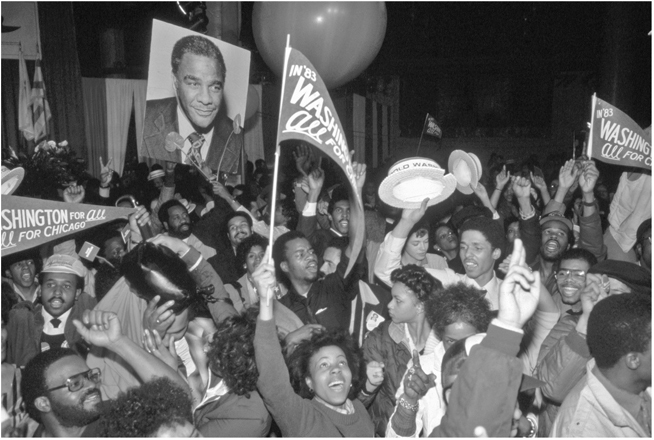

A bright, charismatic young activist named Fred Hampton, who assumed the leadership of the Illinois Black Panther Party in 1968, found himself on COINTELPRO’s high priority list around this time. An electric orator and savvy organizer, Chairman Fred, as he was known within his entourage, had shown great promise by organizing hundreds of youths in the suburbs west of Chicago for the NAACP Youth Council. “Power to the people” was his mantra, and as chairman of the Illinois Panthers, the twenty-one-year-old Hampton quickly began forging ties with activists all over the city—black, white, and Puerto Rican. Hampton was in good company for this mission; among the leaders of the Illinois Panthers were several talented activists, including future congressman (and eventual mayoral candidate) Bobby Rush—the man who in 2000 would deal Barack Obama his first crushing defeat in electoral politics.

Understanding that it suited the needs of the Daley machine to keep these communities in competition with each other for resources and power, Hampton set out in 1969 to assemble what he referred to as a “rainbow coalition” that brought his Illinois Panthers together with the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican street gang turned political organization under the talented leadership of Jose “Cha-Cha” Jimenez, and the Young Patriots, an enlightened group of working-class whites, many of whom were the children of poor white southern migrants who had settled in a “hillbilly” section of the North Side Uptown neighborhood in the 1940s and 1950s. Their fathers had rallied around Confederate flags, but the radical currents circulating through Chicago in the 1960s had turned these Dixie sons into homegrown Marxists with a nuanced understanding of the interplay between race and class. These were strange and exciting times indeed. And even though the Black Panthers, Young Lords and Young Patriots were, as young idealists who dared to extend their hands across racial lines, not exactly mainstream elements of their communities, this astonishing alignment held the potential of establishing a power bloc that brought together the West Side ghetto, the Near North Side Puerto Rican barrios of Humboldt Park and Lincoln Park, and the white working-class sections of the Far North Side neighborhoods of Uptown, Edgewater, and Rogers Park.

Moreover, in an effort to get Chicago’s more powerful gangs behind his project to bring power to the people, Hampton had also made inroads into the Main 21, the governing body of the federation of neighborhood gangs that now constituted the mighty Blackstone Rangers. Many felt that if the Rangers committed to the cause, the Vice Lords and the Gangster Disciples would follow, and the Daley administration would be facing the dreaded alliance of supergangs it had feared for years. However, there was still some work to be done to make this happen. Hampton’s efforts to recruit in Ranger territory, for example, had led to the shooting of a Panther and then a heated sit-down with Jeff Fort that culminated in threats and dozens of Rangers bursting into the room with guns drawn. The Rangers were hostile to any encroachments on their turf, no matter how well intentioned. Yet, Hampton was allowed to walk out of that meeting alive, and in view of his charisma and determination, nobody in City Hall could be too sure that he would not be able to eventually get through to the headstrong Ranger leadership. The twenty-one-year-old was, by the winter of 1969, quite likely the most dangerous man in Chicago, and, as such, he was high up on J. Edgar Hoover’s list of the most dangerous men in the United States.

One can only imagine Hampton’s frustration about the refusal of his brothers in the Blackstone Rangers to accept that neither he nor their brothers in the Disciples were the enemies. What he would never know was how much this mistrust had been sown by informants and infiltrators executing stratagems issued from high up in the FBI. The Rangers were trying to make the transition to community activists, but they still lived by the codes of the streets, which told them that threats to their power and pride could not go unanswered, so it was all too easy for FBI and Red Squad operatives to plant all kinds of rumors and doubts in their heads. The Panthers, on the other hand, were less susceptible to such subterfuges; this was a group that furnished new members with readings lists that included works by Karl Marx and Frantz Fanon. Stopping Fred Hampton would thus require a different approach.

On December 4, 1969, just before dawn, a heavily armed tactical police unit under the command of state’s attorney Edward Hanrahan burst into the West Side apartment at 2337 W. Monroe Street where Hampton and several other Panthers lived and shot nearly one hundred rounds of ammunition at anything that moved or slept. When the guns fell silent, Hampton and fellow Panther Mark Clark lay dead and four other Panthers had been seriously wounded. Hampton had been shot in the head at point-blank range, execution style, while lying in his bed. Ostensibly, the police were there to serve a search warrant for illegal weapons and things got out of hand, but evidence from the crime scene strongly suggested political assassination. The police displayed a pile of weapons that “six or seven” Panthers had allegedly used to fire upon them, a story that was predictably backed up by the city’s investigation into the affair. But a federal grand jury report of the incident issued on May 15, 1970, was highly critical of the city’s handling of the autopsies and ballistics tests, which, according to the report, concealed the fact that Hampton was shot in the head from above and falsified indisputable ballistics evidence indicating that only one of ninety-nine bullets fired could not be traced to police guns. The report revealed hardly anything that most people did not already know, except perhaps the extent to which the machine and its hired guns could act with nearly complete impunity. As is often the case in Chicago, utter desperation about the impossibility of challenging the political order gave way to jaded sarcasm. Mike Royko, who, incidentally, was highly critical of the Black Panthers, remarked in response to Hanrahan’s comment that the police had “miraculously” escaped injury: “Indeed it does appear that miracles occurred. The Panthers’ bullets must have dissolved in the air before they hit anybody or anything. Either that or the Panthers were shooting in the wrong direction—namely, at themselves.”12

Further evidence would surface in the years to come that would shed even more light on the circumstances surrounding Hampton’s murder, and, for that matter, on the entire history of the left during its most pivotal moment on the political stage in the last half century. Reflections on why the left seemed to implode in 1968, opening the door for the backlash and the subsequent conservative ascendency, have often emphasized ideological factors that weakened its ability to rally people behind a coherent, unifying reform project. Some, like SDS veteran and prominent sociologist Todd Gitlin, point to the New Left’s abandonment of liberalism and move to extremist politics, while other, more reactionary commentators lampoon those who took to the streets in the 1960s as drugged-out or sex-crazed freaks driven by senseless rebellion against a society that had bestowed them with only privileges and opportunities. Another interpretation points to the idea that the rise of identity politics in the 1960s splintered the left into so many solipsistic, identity-centered projects—black power, brown power, yellow power, feminism, radical feminism, gay liberation, and so on—that it was no longer possible to build a progressive movement out of blocs that had everything to gain by joining forces against the status quo.13

Largely understated in most accounts of the period is the story of state-sponsored repression, which, as Fred Hampton’s murder so dramatically demonstrates, took the form of a highly sophisticated campaign of countersubversion involving the close cooperation of federal and local authorities. Chicago cops harbored a palpable hostility towards the Black Panthers because they had the audacity to stand up to them with lethal weapons, and Mayor Daley wanted them neutralized because of their increasingly popular breakfast programs in black Chicago and their coalition-building efforts throughout the city. But the FBI, which, like the Daley administration, wanted to see the gangs continue to kill each other off, played a critical role in ultimately closing the book on Hampton and the Illinois Panthers. It was the FBI that had enlisted the help of William O’Neal, who would become the Brutus in Fred Hampton’s very brief life on the political stage. A car thief by trade who had agreed to go undercover to avoid doing hard time, O’Neal was so convincing that by the winter of 1969 he was put in charge of security for the Illinois Panthers. In a story fit for Hollywood, O’Neal furnished the Chicago police with a detailed floor plan of Hampton’s apartment and, according to his own confession, slipped a powerful barbiturate into Hampton’s drinks the night before the raid, which explains why the normally agile Hampton never made it out of his bed during the raid. O’Neal, who was just eighteen at the time, spent the next sixteen years in a witness protection program, after which he returned to Chicago a broken man. In 1990, in the early hours of Martin Luther King Day, O’Neal’s gut-wrenching guilt finally pushed him to try to make his peace with Chairman Fred by fatally throwing himself in front of a speeding car on the Eisenhower Expressway.14

While there is no easy way to assess the impact that such countersubversive activities had on left politics nationwide, the evidence from Chicago is weighty, to say the least. Hampton’s murder was certainly the most dramatic case—the incident that threatened to blow the cover off the whole enterprise—but one would be hard-pressed to find a single political figure on Chicago’s left who did not feel the heat in the 1960s and early 1970s. In Chicago things got hot enough to, as COINTELPRO intended, “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” a generation of activists, some of whom would spend significant stretches of their adult lives in prison on charges they denied.

Although we will never know the entire truth, in view of what Fred Hampton’s murder reveals about the lengths authorities were willing to go in their war on the left, it hardly takes a stretch of imagination to believe that the FBI and CPD would also engage in an extensive campaign of frame-ups. Just three weeks before the raid on the Panthers, Vice Lord leader Bobby Gore, one of the main forces behind the West Side gang’s successful turn towards political activism, was arrested for a murder he maintained he did not commit until his death. Around the same time, State’s Attorney Hanrahan managed to get eighteen indictments (mostly for easily contrived charges of assault and battery on police) against Jose Jimenez in the span of six weeks, an offensive that coincided with Jimenez’s efforts to mobilize the Young Lords against a redevelopment plan in Lincoln Park that would lead to the displacement of thousands of Puerto Rican residents. This was just a few months after United Methodist pastor Bruce Johnson, who had provided his Chicago People’s Church as headquarters for the Young Lords, was viciously stabbed to death in his Lincoln Park home, along with his wife, Eugenia. While we may never know for sure the truth about such incidents, the pieces seem to fit together.

What the events of 1969 tell us is that the brutality on display at the Democratic Convention of 1968 was far from aberrant; it was merely the spectacular coming out of a systematic, banal campaign of political violence that flourished in the new national backlash context of the post-1968 years. Some New Left leaders felt there was something to be gained by flushing this campaign out into the open for “the whole world” to see, but such hopes ultimately proved to be naive. Writing in this precise moment and with the unfolding Chicago story clearly in mind, Hannah Arendt warned in her essay On Violence that “since violence always needs justification, an escalation of the violence in the streets may bring about a truly racist ideology to justify it, in which case violence and riots may disappear from the streets and be transformed into the invisible terror of a police state.”15 This was a fairly accurate way to view what was transpiring in Chicago in the years following the convention. The war on gangs declared by Mayor Daley and his right-hand man Edward Hanrahan in the spring of 1969 represented the symbiotic relationship of racist ideology and police terror; notions of ghetto pathology reduced all black youths to gang members, and, as gang members, youths were thus deemed incapable of anything other than criminal behavior. This, in turn, justified a merciless wave of police repression, which, by criminalizing youths out on the streets, served to prove the point that all black youths were gang members, and all gang members were criminals. Once again, Chicago was in the vanguard of conservative politics. A little more than a decade later, during the Reagan administration’s War on Drugs in the 1980s, municipalities all over the country would seize upon similar antigang offensives to garner federal funds for law enforcement initiatives and win over fearful white middle-class voters.16

And yet, if, as Arendt claimed, violence could destroy power, it was not the only force that was working against the project of bringing “power to the people.” The politics of identity was a double-edged sword for the left in Chicago during this epic moment. The streets of Chicago had always been the place where young people constructed, performed, and negotiated the meanings of their ethnoracial identities—in rituals of play, war, and love. By the early 1960s, during the high times of the civil rights era, these rituals took on an increasingly perceptible political feeling; with the circulation of images and ideas associated with the struggles of young blacks in the South against forms of discrimination at school and in venues of commercial leisure, kids out on the streets defending their communities and their identities began to see themselves as political actors, and local activists were quick to capitalize on this to get people out on the streets for more formal political causes. British sociologist Paul Gilroy has observed that “collective identities spoken through race, community and locality are, for all their spontaneity, powerful means to co-ordinate actions and create solidarity,” a situation that by the end of the 1960s had made a fetish out of the city’s most visible ethnoracial identities.17

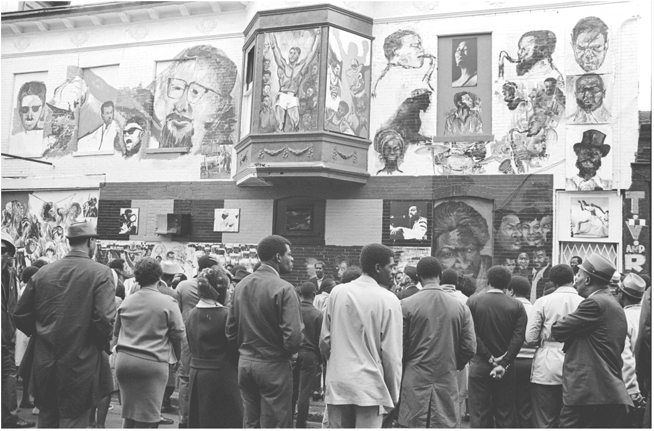

The spiritual, magical, salvational qualities that people attributed to these identities pushed them out into the streets of their neighborhoods to engage in quasi-religious rituals of collective identification. Some of the violence between gangs around this time loosely fit this description, as did uprisings against the police, which could very quickly turn into potent demonstrations of community pride. Such was the case in the often overlooked Division Street riot of 1966, when the Puerto Rican barrio in Humboldt Park seemed to discover its sense of self as it took to the streets to protest the shooting of a local youth by a policeman breaking up a gang scuffle. This was also the context that gave rise to the Chicago mural movement of the early 1970s, which saw aspiring artists in black, Puerto Rican, and Mexican neighborhoods spreading broad swaths of bright paint over drab walls to create vivid scenes of everyday community life that harkened back to the New Deal–era murals influenced by artists like Diego Rivera. The “community mural movement,” as it has come to be known, began in black Chicago before spreading, most notably, to New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. More precisely, it began with the once-famous Wall of Respect at 43rd and Langley—a kind of Mount Rushmore for the black community—which included the faces of fifty black writers, musicians, and political leaders considered to be “black heroes” by the fifteen artists who collaborated on the project in 1967. The Wall became a meeting point for black power groups around Bronzeville and the Kenwood area, a place where the maxims of Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and H. Rap Brown (Martin Luther King’s head was conspicuously absent from the Wall) filled the air, and in 1969 and 1970 it became a rallying point for its own sake, as the city devised an urban renewal plan that would have meant the Wall’s demolition. However, a fire “of unknown origins” rather than urban renewal ultimately destroyed the Wall in 1971, but by then one of its principal creators, William Walker, had already met up with some Mexican and Puerto Rican artists to form the Chicago Mural Group—a multiracial artists’ cooperative that sought to fill the urban landscape with billboards displaying racial and social injustices. One of the finest examples of the work of this collective can be seen today in the Humboldt Park barrio at the corner of LeMoyne and Rockwell, where the mural Breaking the Chains covers the wall of a well-maintained three-story walk-up. Painted by John Pitman Weber, the cofounder of the Chicago Mural Group, along with a number of Puerto Rican residents, the mural depicts black, brown, and white hands breaking chains and reaching up towards the sun.18

FIGURE 13. The Wall of Respect, a site of frequent gatherings in the late 1960s. Photo by Robert Abbott Sengstacke/Getty Images.

Such celebrations of “race, community, and locality” created a level of political engagement by average people in the context of everyday Chicago life that has seldom been approached since. The problem was that the same primordial feelings and attachments that were bringing people into the streets were also reinforcing a logic of ethnoracial difference—a logic already embedded within the city’s ethnoracially balkanized social geography—that made the development of powerful multiracial coalitions a nearly impossible task. We will never know how far Chairman Fred might have taken his “rainbow coalition,” but we do know that, at the time of his death, such notions had, for the most part, captured the hearts and souls of only an avant garde fringe of activists, intellectuals, and artists.

More indicative of how the politics of identity were shaping grassroots progressive politics was the student-led movement to reform Chicago’s high schools in the spring and fall of 1968—one of the last of its kind. Emerging out of a general spirit of discontent about the sorry state of Chicago schools, this movement took the form of two parallel mobilizations—one black and one Latino—from its very first days. Ironically, black and Latino students had similar complaints regarding the Chicago Board of Education’s refusal to recognize their cultural identity and deal with the discrimination they faced at the hands of white teachers, but their demands never found common ground. White students, for their part, largely stood on the sidelines when they were not actively, even violently, opposing their fellow black and Latino students. Harrison High School, located on the 2800 block of West 24th Street, along the border between the Near West Side and Pilsen, found itself in the center of things. The leaders of the militant black student organization the New Breed went to school at Harrison, and the most vocal Latino student organization, a group that included famed Mexican activist Rudy Lozano, also formed here. Harrison was one of the only schools in the city at that time that mixed significant numbers of blacks, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and whites, so it could have served as a stunning example of multiracial cooperation against the machine. But this was not to be. The black, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and white youths at Harrison had come of age in a street culture that placed a premium on defending the boundaries of their ethnoracial communities against outsiders, and these were hard habits to break. If, as Paul Ricoeur has argued, the self achieves identity and meaning through the detour to the other, this process, in the context of Chicago politics, had profound consequences.19 In the end, the board of education had little reason not to accede to the demands of black and Latino students. And so Superintendent James Redmond pledged to extend the half-year Afro-American history course being offered in thirty-six high schools to a whole year, to purchase new textbooks that “placed greater emphasis upon contributions of minority groups,” to pursue “efforts to achieve a racial integration of staff throughout the system,” and to strengthen relations with parent-teacher associations (PTAs) and student groups.20 The board of education had effectively institutionalized the politics of identity, a situation that did little to change the fact that public school system was heading straight towards the precipice.

SKYSCRAPERS, MARTINIS, AND FUTURES

Perhaps more than any other city in the United States, Chicago today captures with stark clarity the contrast between wealth and poverty that American-style free-market capitalism produced over the long twentieth century. What makes the contrast so vivid is the spatial proximity of the two extremes. In Chicago, one can board an “L” train amidst the bustling avenues of the Loop business district, where an army of chauffeurs, valets, and doormen expedite business executives through revolving doors and into the stately lobbies of firms whose influence stretches to the far corners of the world, and minutes later be looking down from the elevated tracks at the hyperghetto, where boarded-up buildings and litter-strewn vacant lots mark a land that time forgot. In some areas of the hyperghetto, the main signs of commercial activity are hand-to-hand drug sales, liquor stores, and currency exchanges, where those without proper bank accounts can cash checks and pay utility bills for hefty fees. The only institutions competing with liquor stores for customers in need of medicine for the soul are storefront churches.

Chicago’s hyperghettos are not so different from ghetto neighborhoods in several of the other midwestern and northeastern cities that constitute the American Rust Belt, and they share a similar story of deindustrialization, urban decline, and white flight that reshaped much of the northern metropolitan United States in the postwar decades. Between 1947 and 1982, factory employment in Chicago dropped from 688,000 to 277,000 (59 percent), a period that also witnessed a steep decline in Chicago’s middle- and upper-income families—some 30 percent between 1960 and 1980 alone. Between 1947 and 1982, moreover, Chicago’s share of the metropolitan-area job market dropped from 70.6 percent to 34.2 percent, a decrease that was due not only to the loss of manufacturing work in the city but also to the increase in suburban jobs.21 Some of these losses of jobs and people were associated with the suburbanization that the federal government had set in motion with a range of subsidies that placed homeownership within the reach of middle-class citizens who before the 1940s could have only dreamed of owning a home. The 1960s and 1970s saw the rapid growth of Chicago’s posh North Shore railroad suburbs, as well as the suburbs of DuPage County to the west.

Already by the end of the 1960s, these processes had caused Chicago to lose its place as “second city” to Los Angeles, whose population of 10 million easily surpassed the 7.8 million inhabitants in its greater metropolitan area. But things took a sharp turn for the worse in the 1970s, when, within a national economy disrupted by oil shocks and stagflation, Chicago lost 15 percent of its retail stores, 25 percent of its factories, and 14 percent of its jobs, and Chicago families experienced a 10 percent fall in real income.22 Moreover, while per capita personal income did still rise during this decade, the pace lagged behind Detroit, Milwaukee, Cleveland, and St. Louis, and by 1981 it was just 4 percent above the national average (whereas in 1965 it had been 30 percent higher than the national average).23 The devastation wrought during these years was made visible by the 1980 census, which indicated that ten of the country’s sixteen poorest neighborhoods were in black Chicago. If times were hard in the 1970s, black Chicagoans bore the brunt. Between 1963 and 1977, when the city as a whole lost 29 percent of its jobs, black Chicago’s drop was 46 percent.24

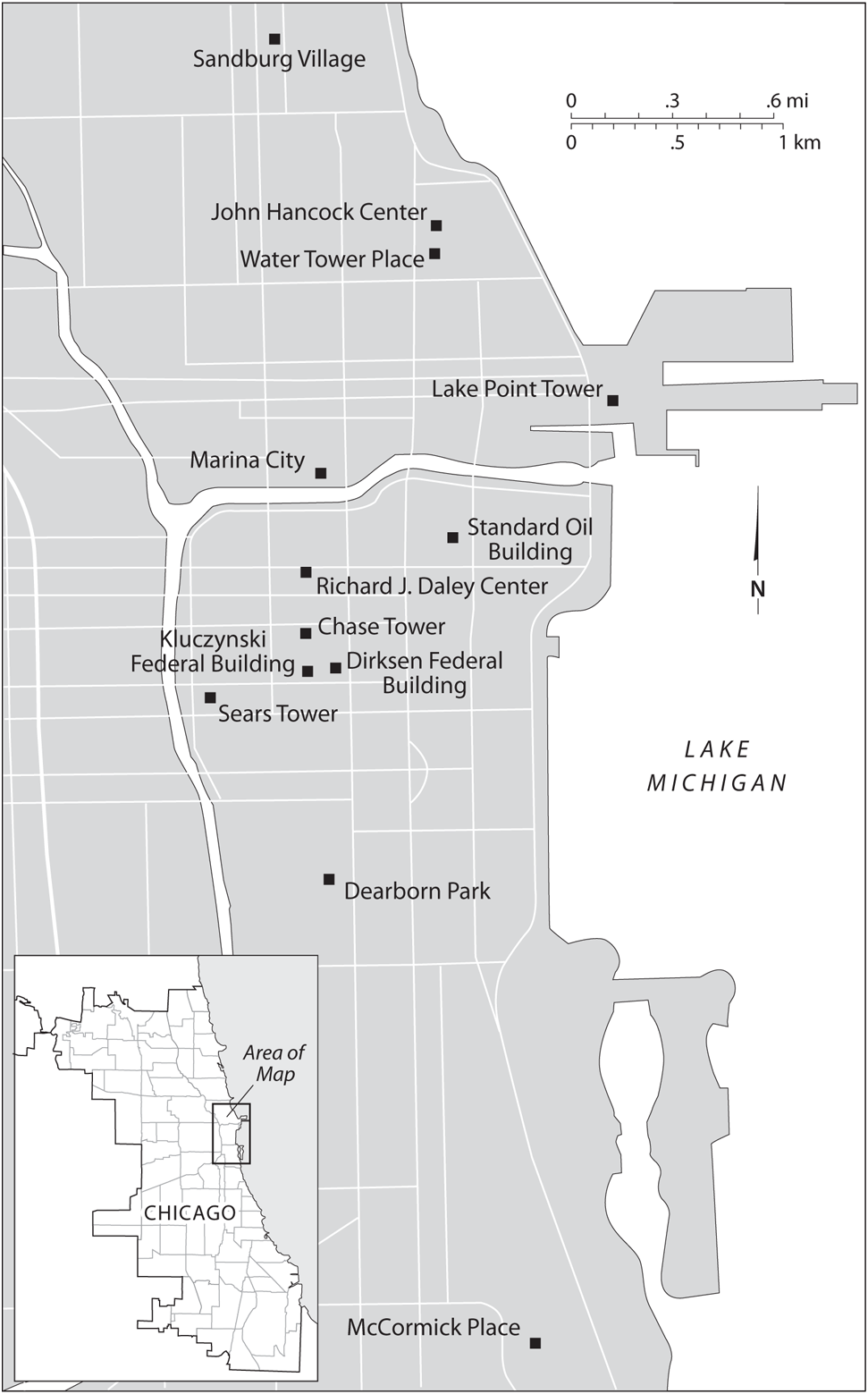

Yet it is misleading to think of this decade and the turbulent years leading up to it as a period of doom and decline. By the early 1970s, one could behold in the Chicago sky a number of majestic steel and glass structures stretching towards the clouds—symbols of a city on the rise. Between 1968 and 1975, work was completed on five of the ten tallest buildings that would define the contours of Chicago’s skyline at the end of the twentieth century: the John Hancock Center (1968), the Chase Tower (1969), the Standard Oil Building (1972), the Sears Tower (1973), and Water Tower Place (1975), along with what was at the time the tallest residential building in the world, Lake Point Tower (1968).25 Just when the action on the streets was at its hottest, the city, with the help of the internationally renowned architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, was doing all it could to move its precious white-collar professionals into secure, air-conditioned cubicles in the sky. If the 1920s witnessed the first great vertical move of American cities, a second wave of skyscraper construction occurred in the late 1960s and 1970s, when work was completed on a number of the buildings that would become the well-recognized landmarks of the country’s great urban centers—the World Trade Towers in New York City, the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco, the John Hancock Building in Boston, and the Sears Tower in Chicago.26

FIGURE 14. The Chicago skyline looking north from the South Loop lakefront, 1974. C. William Brubaker. C. William Brubaker Collection, bru005_11_oF, University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

At first glance, the timing of this skyscraper boom may seem rather enigmatic. Normally, such capital-intensive projects thrive in relatively risk-free market circumstances, and, while credit had been lined up and ground had been broken on some of these buildings a few years prior to the global economic doldrums that followed the Arab-Israeli War and OPEC oil embargo of 1973, the U.S. economy had already been showing signs of instability by 1966, when corporate productivity and profitability began to decline, provoking a credit crunch in 1966 and 1967. With increasing competition from Japan, Western Europe, and a number of newly industrializing countries, the U.S.-dominated international economic order that had been established by the 1945 Bretton Woods agreement broke apart at the end of 1971, and with it, its system of fixed exchange rates that tied currencies all over the world to the gold-backed U.S. dollar. These were thus precarious times to be investing in large-scale infrastructural projects whose success depended on strong economic growth. New York City was facing bankruptcy and Chicago’s financial condition was hardly rock solid. In 1971 the stockyards closed down for good and the steel mills were on the verge of a significant decline. Moreover, Illinois was struck with a sharp drop in defense contracts in the 1960s and 1970s, another factor that weighed heavily upon the local economy. By the end of the 1970s, the credit-rating agency Moody’s downgraded Chicago’s bond rating, and the school system was facing a major budget shortfall. And yet, despite all this, the buildings kept moving skyward.

As the old industrial order was crumbling, a new economic order was already rapidly taking shape, and Chicago was vying for a central place within it. Scholars like David Harvey and Saskia Sassen have described this moment as one of deep structural transformation for the world economy, as the postwar framework of Fordism and state managerial Keynesianism collapsed and out of its remains emerged a new system characterized by more flexible labor arrangements and new sectors of production based on the provision of specialized financial services for an increasingly globalized economy.27 For Sassen, in particular, such momentous changes would have major consequences for a group of new “global cities” that would take on strategically critical roles “as highly concentrated command points in the organization of the world economy” and “key locations for finance and for specialized service firms.”28 FIRE (finance, insurance, and real estate) activities would come to dominate the new “producer services” orientation of these global cities, along with marketing, advertising, employment, and legal services. The rise of these new service industries, in turn, would have a powerful impact on urban form, especially on the spatial layout of downtown business districts. Although many observers of the urban scene at the time believed that recent advances in telecommunications technologies would make high-density business districts obsolete, a very different scenario came to pass; the internationalization of corporate operations instead transformed the cores of global cities into dense concentrations of service providers capable of exercising centralizing functions over sprawling commercial activities.

The consequences for Chicago—once the “city of the big shoulders” and “hog butcher to the world”—were nothing short of spectacular. By 1980, Chicago’s central business district, which covered just 3.5 percent of the city’s total surface area, accounted for roughly 40 percent of the city’s property taxes. Moreover, while the city as a whole lost nearly one-quarter of a million jobs during the 1970s, white-collar employment in the Loop rose at a respectable pace. In effect, Chicago was turning the corner towards its future as the nation’s third-ranking global city, with a (4.2 percent) share of the total national employment in producer services that placed it close behind Los Angeles (with 4.6 percent) and far ahead of fourth-place Houston (with 1.7 percent).29 In the insurance sector, it was second only to New York—a position symbolized by the black fortress-like tower that Skidmore, Owings & Merrill designed for its developer and tenant, the John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company. At one hundred stories and 344 meters, it was at the time of its completion the tallest building in the world outside Manhattan, and, although credit problems halted its construction in 1967, it was ready to serve as a backdrop to the combat that reigned in the streets during the summer of 1968. This was, in part, its function, even if few involved in its construction would have thought of it in this way at the time.

Guy Debord seized upon the notion of “spectacle” in 1967 because it was elemental to the epic struggle that was transpiring in this pivotal moment in the history of capitalism. “The period from 1965 to 1973 was one in which the inability of Fordism and Keynesianism to contain the inherent contradictions of capitalism became more and more apparent,” David Harvey has argued.30 In the United States a range of protest movements had made the streets and neighborhoods of American cities into spectacles of this crisis, notably during Chicago’s Democratic National Convention of 1968. As ineffectual as the Yippies may have seemed to many, they helped hijack the Daley administration’s attempt to create a spectacle of prestige and power and to transform it into one of ignominy, violence, and disorder. This posed a potential threat to the city’s livelihood in a moment when its political leadership was trying to project an image of order and progress to all the investment capital beginning to fly around the globe.

To understand the stakes, one needed only to cast a sidelong glance at Detroit, where the spectacle of rioting and black power anger prevailed in the years after the 1967 riot, a situation from which the city never recovered. Thereafter, the name Detroit—previously known as the “arsenal of democracy” and the “Motor City”—evoked images of burning ghettos and middle-class whites taking target practice in the suburb of Dearborn, preparing for the race war to come. That the city was never able to counteract this spectacle explains a great deal about why Detroit failed to keep either its white middle class or the companies they worked for within its limits, and why it would never attract enough service firms to make it into a global city. Chicago, on the other hand, had as much ugly spectacle as Detroit to contend with, but it seemed able to repel the stigma of each seemingly disastrous episode with astonishing ease. Chicago made it through the late 1960s and 1970s with its sense of civic pride intact, even if its civic pride had become an exclusively white feeling. But even to maintain the civic pride of the white middle class was a feat during this period of urban decline and white flight, when the American dream lay beyond the noisy, polluted urban landscape in the leafy outlying suburbs, and Chicago’s ability to accomplish this owed a lot to its mayor. Every time the city seemed on the verge of falling apart, Chicagoans rallied around their mayor. And their mayor seemed to understand just what needed to be done to take his city into the global age.

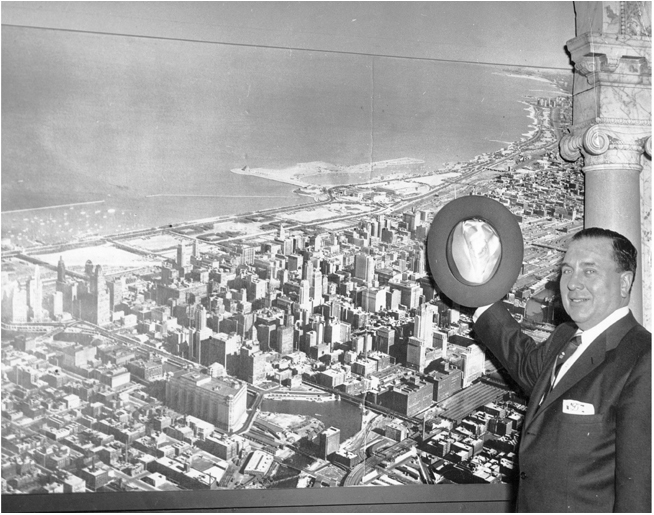

Daley was ferociously proud of his city, and his pride was infectious, but the resilience of Chicago’s civic spirit was due to the fact that it was embedded within the city’s physical environment. Between 1960 and 1965, Chicago became the kind of city that middle-class whites could feel good about living and working in, and Daley played a key role in making this happen. In fact, he was merely following the blueprints of the 1958 “Development Plan for the Central Area of Chicago,” which had singled out for “special emphasis . . . the needs of the middle-income groups who wish to live in areas close to the heart of the City.”31 In the context of 1958, the phrase middle-income groups meant white people, and the “needs” being referred to were luxury housing and the kinds of leisure and retail resources that would keep these people happy. The idea being voiced by Loop business leaders, especially retailers and developers, was that the central business district was in danger of being overrun with black pedestrians and shoppers and desperately needed an infusion of white middle-class residents. Developer Arthur Rubloff, a major player in the transformation of Chicago’s Near North Side, captured this view perfectly when he famously remarked, “I’ll tell you what’s wrong with the Loop, it’s people’s conception of it. And the conception they have about it is one word—black. B-L-A-C-K. Black.”32

Rubloff, who, at the time of his death in 1986 possessed a wardrobe that included one hundred hand-tailored suits, forty cashmere coats, five hundred silk ties, one hundred pairs of shoes, and fifteen tuxedos, had been eyeing the area north of the Loop since 1947, when he had coined the term Magnificent Mile to capture his vision for a major upscale commercial strip to be built along North Michigan Avenue, from the Chicago River to the ritzy Gold Coast neighborhood. In 1960 Daley moved to make Rubloff’s dream into reality when he cleared the way for a massive redevelopment project to the southwest of the Gold Coast, using $10 million of federal grant money to acquire and bulldoze a sixteen-acre strip bounded by North Avenue and LaSalle, Clark, and Division Streets. Of course the city made a call for tenders on the project, but, predictably, the Rubloff Company landed the contract with its plan for a $40 million middle-class housing development, complete with town houses, high-rises, swimming pools, tennis courts, and playgrounds. The development would be named Carl Sandburg Village—after, ironically enough, the poet who had so brilliantly evoked the hopes and frustrations of the kind of working-class people the project would be displacing. The overwhelmingly white middle-class Sandburg Village made the area a lot less diverse, replacing a sizable community of Puerto Ricans and the small Japanese “Little Tokyo” neighborhood around Clark and Division, but that was precisely the point. The city now had its barrier protecting the Gold Coast from the Cabrini-Green housing project, and the Loop, along with its Magnificent Mile extension, had a vital infusion of white middle-class residents and shoppers. And this was only the beginning.

Around the time that bulldozers were making way for Sandburg Village, builders were breaking ground at the other end of the Magnificent Mile on Marina City—a $36 million residential complex consisting of twin corncob-shaped, sixty-five-story towers on the north bank of the Chicago River at State Street. Advertised as a “city within a city” with such built-in amenities as a marina, a gymnasium, a movie theater, a swimming pool, an ice rink, a bowling alley, restaurants and bars, a parfumerie, and a gourmet shop with “items gathered from all over the world,” Marina City was a monument to the slick, sophisticated urban lifestyle that Madison Avenue was concocting in the mid-1960s to sell everything from automobiles to hi-fi stereos.33 The idea was a smashing success. Marina City’s nine hundred apartments were fully rented before the building even opened in 1965, providing the Loop with another concentration of solid middle-class residents on its northern border and thousands of shoppers perched at the southern edge of the rapidly developing Magnificent Mile. And once again it was Daley who worked behind the scenes to close the deal. In fact, the whole thing was a classic machine boondoggle, with the city selling the riverfront property at a considerable discount off its market value to CHA board chairman Charles Swibel, who then procured financing from the Janitors International Union, whose president, William McFetridge, was a close friend of Daley.34

The same year Marina City was completed, work began on Lake Point Tower, another utopian “city within a city” development that would further guarantee that the Near North Side would be filled with well-to-do white professionals into the foreseeable future. Overlooking Navy Pier just north of the mouth of the Chicago River, this two-hundred-meter-high, black undulating glass tower was designed by two students of Mies van der Rohe who were inspired by his 1922 design for a glass-curtained skyscraper in Berlin. In addition to offering truly breathtaking views of both city and lake, residents there enjoyed their own two-and-a-half-acre park that included a playground, swimming pool, duck pond, and waterfalls.

FIGURE 15. Daley, the builder, ca. 1958. Richard J. Daley Collection, RJD_04_01_0040_0005_0122, University of Illinois at Chicago Library, Special Collections.

Carl Sandburg Village, Marina City, Lake Point Tower, and the swanky stores opening up on North Michigan Avenue represented the new corporate image of white-collar Chicago and the suave lifestyle of urban consumerism and indulgent leisure that came with it. Every day at 5:15 P.M. the bartender at the Marina City bar rang a bell signalling that customers could claim 5-cent refills. Chicago was quickly redefining itself as a city that knew how to swing—a public relations coup that owed a lot to Frank Sinatra’s popularization of the song “My Kind of Town (Chicago Is)” in 1964 and Hugh Hefner’s opening the first Playboy Club on Walton Street in the heart of the Gold Coast. During its first three months in 1961, Hefner’s club attracted 132,000 guests; by the end of the year, it had 106,000 members, each one possessing a metal key topped with Playboy’s trademark bunny head. An astonishing number of people were thus flashing bunny keys around the city, and, even if a good many were out-of-towners who frequented the club when in town on business, the implications were the same. Chicago was a corporate city on the make, and this had profound consequences for its public culture and for its politics.

MAP 6. Major Loop building projects, 1963–1977.

Symbolic of the broader cultural change under way was Playboy Magazine’s 1965 move into the thirty-seven-story art deco Palmolive Building, replacing, ironically, toothpaste- and soap-maker, Colgate-Palmolive-Peet. With its prominent location behind the famed Drake Hotel at Lake Shore Drive’s sharp Oak Street Beach bend, the prestigious 1929 building became a billboard for Playboy, whose name was spelled out on its top floor with nine-foot-high illuminated letters. Playboy was on the rise—in 1972 an estimated one-quarter of all American college men bought the magazine every month—and its genesis in Chicago was critical to its mass appeal. It was further testament to the fact that the cultural essence of Chicago was not to be found in coffeehouses and folk clubs but rather in the bars and nightclubs on the Gold Coast’s Rush Street strip, where many of the top jazz and blues performers played and got paid. This explains why in 1969, the Weathermen, an SDS splinter group advocating violent tactics to shake the country out of its self-satisfied stupor, attacked nightclubs on Rush Street in the infamous “Days of Rage” riot; such radicals understood, if perhaps only subconsciously, that these nightclubs were somehow as emblematic of the capitalist order they were opposing as banks and military contractors.

Although Chicago earned its credentials in the 1960s as a city that could play, it would soon come to be known as “the city that works.” The description, first used in a 1971 Newsweek article lauding Mayor Daley’s ability to create an efficient infrastructure for business and everyday urban life when other cities were floundering, conveyed a double meaning: that Chicagoans worked hard and that their mayor made the city work efficiently for them. “But it is a demonstrable fact,” Newsweek reported, “that Chicago is that most wondrous of exceptions—a major American city that actually works.”35 The phrase began appearing in local newspapers by 1972, and then in the Washington Post and New York Times in 1974 and 1975. Chicago had defined its brand, so much so that by the time Mayor Daley died of a heart attack in office in 1976, the phrase was run at the top of his obituary in newspapers nationwide. Yet the nickname was not merely the result of some kind of brilliant public relations campaign. Chicago became “the city that works” by the early 1970s in part because while other cities were dealing with crumbling infrastructures and deficient services in the midst of a generalized fiscal crisis, it had already managed to upgrade—often with the use of other people’s money—its transportation and municipal infrastructures.

By the end of 1960, Mayor Daley had overseen the completion of the badly needed Northwest Expressway (renamed the John F. Kennedy Expressway in 1963) out to O’Hare International Airport, most of which had been paid for with federal highway funds, and by 1970 the Blue Line of the “L” was conveying commuters out to the airport on its median strip. In 1961, moreover, O’Hare got a $120 million makeover financed without a penny of taxpayer money; Daley had driven a hard bargain and forced the airlines themselves to put up a forty-year bond to pay for the project, which helped make O’Hare the busiest airport in the world. And many of those arriving in Chicago would be there to attend a convention at Chicago’s new McCormick Place convention center. Then, in 1964, work was completed on a spectacular modernist federal government complex at Jackson and Dearborn, designed by Mies van der Rohe in the International Style, consisting of the thirty-story Dirksen Federal Building, the forty-five-story Kluczynski Federal Building, and a United States Post Office station around a spacious plaza. Once again, Daley had marshalled considerable federal funding to get the work done.

The following year was the occasion for another ribbon-cutting ceremony, when the city opened its magnificent new Chicago Civic Center (renamed the Richard J. Daley Center in 1976) between Randolph and Washington, across from City Hall. Yet another International Style skyscraper with an expansive modernist plaza, the center, which would house the county court system along with office space for both the city and county governments, was constructed with a special steel that was designed to rust, giving the building its distinctive red and brown color. Two years later, in 1967, Pablo Picasso completed a fifteen-meter-high, 162-ton cubist sculpture, made of the same material as the building it fronted and paid for with grants from local charitable foundations, to adorn the Civic Center plaza. When asked to approve the choice of Picasso for the project, Mayor Daley allegedly replied, “If you gentlemen think he’s the greatest, that’s what we want for Chicago, and you go ahead.” The “Chicago Picasso” was the first of a series of high-profile works of art that would bring a sense of worldliness to downtown Chicago. This was important for a city trying to cast off its image as blue-collar and obtuse. In 1974 the Federal Plaza got its own artistic landmark—Alexander Calder’s 16-meter-high, red steel Flamingo.

The Loop thus morphed into a vision of modernity, efficiency, and prestige at the very moment when American corporations were seeking to project these same attributes, and thus feared getting trapped within decaying cities stigmatized by high crime rates and racial tensions. Hence, with companies looking to the inviting suburban environs of Cook and DuPage Counties, where the McDonald’s Corporation would move its Loop headquarters and open its Hamburger University training center in 1971, Daley was able to make a viable case that Chicago was a good place to do business. But even with elegant Miesian skyscrapers, internationally recognized artworks, state-of-the-art residential developments, a burgeoning shopping district, a first-rate airport, and a highway network that enabled Loop professionals to make the daily commute from the desirable towns to the west and north, the mayor was working against strong forces pulling towards greener suburban pastures. DuPage County’s labor force doubled during the 1970s, and its population grew by 34 percent as numerous research facilities and corporate headquarters joined McDonald’s, AT&T, and Amoco along Route 5. During this same period Cook County’s “golden corridor” of high-tech companies quickly formed to the northwest, with Motorola, Pfizer, Honeywell, Western Electric, and Northrup Defense Systems setting up operations along the Northwest Tollway by O’Hare. Similar suburban high-tech corridors were taking shape in many of the nation’s metropolitan areas, a phenomenon that sucked tax dollars out of inner cities at time when they were most in need.36 In Chicago, Mayor Daley approved an 18 percent increase in property taxes in 1971, but this was not nearly enough to offset the loss in tax revenues from the flight of residents and businesses. In 1970, property taxes funded 39 percent of the city’s budget; by the end of the decade this figure had dropped to 27 percent.37

Such circumstances required extraordinary measures, and Mayor Daley, “the builder,” as some referred to him, worked tirelessly behind the scenes to close deals, get tall buildings constructed, and keep major corporations within the city. In 1964, he expedited the sale of a piece of land owned by the city so that work could begin on the First National Bank Building (now called the Chase Tower), a sixty-story curved granite building that opened in 1969 on Madison Street, between Dearborn and Clark.38 In fact, 1969 was a banner year for the Loop, with the opening of eight new buildings that provided an additional 4.6 million square feet of office space. It was also the year that work began on the city’s next tallest building, the $100 million, eighty-three-story Standard Oil Building, the result of another successful campaign by the mayor. Daley had moved quickly to arrange the company’s purchase of vacant land just north of Grant Park after being informed by Standard Oil’s chairman, John Swearingen, that the company had outgrown its South Michigan Avenue headquarters and was looking to move elsewhere. Around this same time, Daley also heard that Sears, Roebuck and Co., the largest retailer in the world, was considering new headquarters in the suburbs, and again went to work on preventing this from happening. After a sit-down with Daley, Sears’s chairman, Gordon Metcalf, announced plans for constructing the world’s tallest skyscraper just west of the Loop. The only problem was that the parcel it wanted was bisected by a segment of Quincy Street. Faced with this dilemma, Daley ordered the city council to hastily authorize transferring ownership of the street to Sears for a very low price, and to make the deal even sweeter, he assured Metcalf that the city would cover the costs of relocating water and sewer lines for the new building. The offer was accepted: when the Sears Tower opened its doors in 1974, Chicago possessed a skyscraper that reached higher than the World Trade Center towers. Not only did this give Chicago a new symbol of prestige, but the $150 million it took to build the tower would also irrigate the local economy, and thousands of white-collar jobs, along with a good many of the professionals who worked them, would remain within the city.