SEVEN

A City of Two Tales

HEAT, HIGH SCHOOLS, AND INEQUALITY

On Thursday, July 13, 1995, the temperature in Chicago rose to a stifling 106 degrees, but it was actually much hotter than that. Meteorologists reported that the more critical heat index, which measures the temperature a person actually feels, could reach as high as 120 degrees. Chicago’s numerous brick apartment buildings transformed into ovens, roads buckled and cracked, city workers sprayed bridges to keep them from locking up, power outages left some fifty thousand residents without electricity for days, and a number of neighborhoods lost water pressure as a result of the many fire hydrants being opened by folks desperate for relief from the heat. In the hottest hours of the day, Chicagoans crowded into air-conditioned movie theaters and department stores or headed to the lakefront to wade into the cool water. But after sundown those without air conditioners or without the power to run them faced sleepless nights in sweltering apartments. On Friday, July 14, the heat index surpassed 100 degrees for the third consecutive day, and, since the human body can withstand such temperatures for only about 48 hours, thousands of city residents began to require medical attention, and more than one hundred died of heat-related causes.

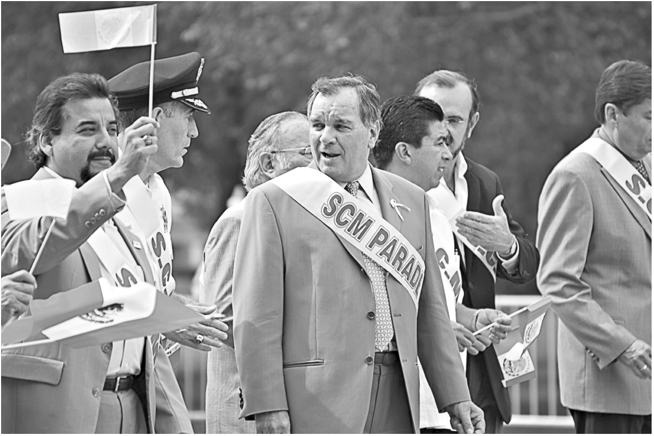

With reports of rising death tolls and complaints of power and water problems multiplying, the mayor faced reporters about the situation for the first time that afternoon. Much like his father, Richard M. Daley was famous for bungling phrases or for seeming obtuse and insensitive. And since his election in 1989, he had almost always seemed annoyed when members of the media dared to question him.1 “It’s very hot, but let’s not blow it out of proportion,” he blurted. “Yes, we go to extremes in Chicago, and that’s why people like Chicago—we go to extremes.”2 But by the end of the weekend, as the heat wave continued and stories of strained emergency services and a city morgue overwhelmed by dead bodies circulated throughout the local media, the mayor began to regret having taken such a dismissive tone and went into political damage-control mode. It was a blizzard, after all, that had sunk Mayor Bilandic not so long ago. A press conference was set up on Monday, and this time the mayor appeared alongside his health commissioner, Sheila Lyne; his human services commissioner, David Alvarez; his fire commissioner, Raymond Orozco; and his police superintendent, Matt Rodriguez. Despite the fact that Chicago newspapers had been warning of the grave dangers posed by the heat wave as early as July 12, the mayor argued that the city had been initially unaware of the gravity of the situation, but had then acted assertively and effectively. Then, in an effort to deflect blame, he railed at power company Commonwealth Edison for its inept response and threatened an investigation. Perhaps the most telling moment of the press conference came when Fire Commissioner Orozco stepped in front of the microphone and proceeded to redirect blame for heat-related fatalities onto the victims themselves. “We’re talking about people who die because they neglect themselves,” he claimed. “We did everything possible,” he added, “but some people didn’t even want to open their doors to us.”3 When temperatures finally dropped to more tolerable levels, an estimated 739 Chicagoans had died as a result of the heat wave—more than twice the number that perished in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.4

Like the flood of 2005 that destroyed much of New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina, the 1995 Chicago heat wave has been remembered as a “natural disaster,” an idea that obscures the policies and social values that left certain residents—mostly the poor and the elderly—overexposed to the deadly possibilities of the elements. Just as thousands of lives in New Orleans would likely have been spared had the federal government invested more money in the city’s levee system and had the local government made serious efforts to evacuate its less mobile residents, hundreds of those who perished in the Chicago heat would have survived had the city responded more effectively to those in need, and, perhaps even more importantly, had years of social neglect not left residents of the black West and South Sides in such precarious circumstances. In his brilliant “social autopsy” of the Chicago heat wave, sociologist Eric Klinenberg found that the much higher incidence of heat-related deaths in black ghetto areas was caused by a “dangerous ecology of abandoned buildings, open spaces, commercial depletion, violent crime, degraded infrastructure, low population density, and family dispersion,” which tended to undermine community life and to isolate elderly black residents.5 In neighborhoods like North Lawndale, for example, where in 1995 there was about one violent crime for every ten residents, many old people remained in their overheated homes out of fear of being victimized on the streets. And such fears were far from groundless. Even though the heat wave produced a moderate drop in crime around the city, the Chicago Police Department nonetheless recorded 134 narcotics arrests, 50 assaults, and 2 homicides in the North Lawndale district for just that week.6

As the preceding chapters have shown, such conditions were shaped by a series of policies implemented between the 1950s and 1980s that tenaciously directed investment capital towards the Loop, reinforced the segregated spatial order of the city, and turned away from the critical challenge of stemming the flight of people and jobs out of Chicago’s expanding ghetto. The consequences of such policies were clear in the North Lawndale neighborhood, where the population dropped from over 120,000 in 1960 to just over 40,000 in 2000, a decline that was hastened in the late 1960s and 1970s in particular, when International Harvester closed its factory there (in 1969) and Sears moved its headquarters out of the neighborhood and into the Sears Tower downtown. Back in those years, as Daley Sr. courted Sears CEO Gordon Metcalf, little thought was paid to the people of North Lawndale that Sears was leaving behind. The same had been true more than a decade earlier, when Boss Daley had rejected a proposal to build the city’s University of Illinois campus in neighboring East Garfield Park, a move that would have helped to stabilize the economy and real estate market of a large swath of the West Side.

But, if a long history of neglect had made neighborhoods like North Lawndale and Woodlawn the kinds of places that were relatively easy to die in for young and old alike, more immediate circumstances also played a large part in the tragic story of the heat wave—circumstances that revealed a great deal about the direction Chicago was heading under Mayor Richard M. Daley’s stewardship in the 1990s. While it is easy to point to the extraordinary conditions brought about by the heat wave—”Let’s be realistic, no one realized the deaths of that high occurrence would take place,” Daley had told the press—Klinenberg’s “social autopsy” reveals that it was, above all, the city’s approach to urban service provision that had made it unable to respond to the situation at hand. Under Daley, Chicago city government had become what Klinenberg refers to as an “entrepreneurial state” characterized by deregulation, fiscal austerity, unprecedented outsourcing of services to private organizations in the name of cost-cutting, the promotion of market solutions to public problems, and the guiding assumption that residents should be treated as individual consumers of city services.7

In the broiling Chicago heat, such practices became life-or-death issues for those without the means or capacity to fend for themselves. Directives from City Hall to reorganize, streamline, and outsource key emergency and social services hindered the city’s capacity to locate and respond rapidly to those in need, and Daley’s celebrated Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy (CAPS) program, which had been launched the year before with federal funding via the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, failed miserably to deliver the kinds of services it was designed for. CAPS was intended to restructure police work so that beat officers became intimately familiar with the communities they patrolled, thus enabling them to take on roles beyond simple law enforcement—as neighborhood organizers, community leaders, and liaisons to social service providers and city agencies. As idealistic as this might have sounded, it was also a strategy for maintaining low-cost social service provision in a period when federal and state funding for welfare programs was drying up; since the end of Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty, Republicans had been crusading for cost-cutting welfare reform, a project that President Clinton effectively completed when he signed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996.

The orientation of police officers towards the field of social work was symptomatic of such national trends and symbolized how degraded the very meaning of social support had become after decades of antiwelfare rhetoric. It was also emblematic of a wave of urban revanchism—a demonization, criminalization, and disciplining of the poor—that geographer Neil Smith has compared to the Parisian elite’s treatment of the laboring classes in late nineteenth-century France.8 The police officers themselves resented being cast as “soft services” providers, and their reluctance to fill these roles made them ineffective in doing the kind of legwork it would have taken to save the lives of the many elderly residents who died in the Chicago heat.9 And yet, when the time came to analyze how the system had failed the poor and elderly who had perished, the knee-jerk response by officials like Fire Commissioner Orozco was to blame the victims. This was no slip of the tongue. Orozco’s reaction reflected racially infused, neoliberal notions that had been circulating within circles of urban governing elites for years—racially infused in their manner of linking up with time-worn ideas of dysfunctional ghetto culture; neoliberal in their tendency to privatize and individualize issues that in the past had been viewed as public or social in nature.10

Scholars have described the ideas and policy approaches that had such lethal consequences during the Chicago heat wave as characteristic of a broad shift to “neoliberal” modes of urban governance in cities all over the world beginning in the 1980s.11 That is to say, Richard M. Daley’s style of governing was part of a larger historical transformation that was hastened on the international level by the programs of Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, and Helmut Kohl to restructure the state so as to promote unfettered free trade, reduce both taxes and public costs, and privatize property, services, and social support systems. However, even though Daley most likely never even uttered the word neoliberalism, it would be mistaken to overlook the role he played in encouraging the hegemony of this rationality in municipal governing circles. Chicago became the poster child for such policies during Daley’s twenty-two years as the city’s “CEO,” the title those in his entourage fittingly bestowed on him, when he guided the transformation of Chicago from a cash-strapped Beirut on the Lake into a bustling global city and world-class tourist destination. By the end of his first full term in office, Daley had turned a $105 million budget deficit into a surplus by reducing the city payroll, reorganizing City Hall, and raising water and sewer rates. During Daley’s more than two decades in office, Chicago added more private sector jobs than Los Angeles and Boston combined; its crime rates generally dropped; its high school standardized test scores and graduation rates climbed; its population grew; its real estate market flourished; and the city became number one in the nation in green roofs, square footage of convention space, and annual domestic business-travel visitors.

The list of such successes goes on and on, and, when taken alongside the remarkable feat of being reelected five times without ever breaking a sweat, it is hard not to conclude that Richard M. Daley was, in many respects, the “greatest” mayor of his generation. Edward Rendell, a two-term mayor of Philadelphia in the 1990s before becoming governor of Pennsylvania in 2003, went so far as to call Daley “the best mayor in the history of the country.”12 One can thus be sure that Daley’s policies were the buzz among municipal officials at both the U.S. Conference of Mayors and the National League of Cities. Although there is perhaps no better sign of the truly national scope of Daley’s influence than the number of officials and advisors he appointed who went on to walk the carpeted halls of President Barack Obama’s White House. Arne Duncan, who was Daley’s CEO of Chicago Public Schools between 2001 and 2009 served as the United States secretary of education; Valerie Jarrett, Daley’s chief of staff, became one of President Obama’s closest advisors; David Axelrod, Daley’s chief campaign strategist and advisor for nearly twenty years, served as the White House senior advisor for Obama’s critical first three years in office; Rahm Emanuel, who headed Daley’s fund-raising efforts for his first successful mayoral run, was Obama’s White House chief of staff before becoming the mayor of Chicago in 2011; even First Lady Michelle Obama, worked for two years in Daley’s City Hall as an assistant to the mayor and as a planning official. Moreover, while never formally a member of Daley’s administration, William Daley, the mayor’s youngest brother, took over the role of White House chief of staff when Emanuel left to run his mayoral campaign. In view of all the links between Daley’s City Hall and Obama’s White House, it would be hard to argue that the political sensibilities that suffused the Chicago success story of the 1990s and first decade of the twenty-first century did not shape the Obama administration in significant ways.

And yet Obama was never comfortable with this idea. For example, when asked during a 2003 interview with Chicago Tribune reporter David Mendell if he thought it would have been a better idea to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods rather than on the construction of Millennium Park in the Loop, Obama, at the time an Illinois state senator planning a U.S. Senate run, responded, “If I told you how I really felt, I’d be committing political suicide right here in front of you.”13 Whether due to sheer political expediency or to Obama’s increasingly pragmatic orientation, such ambivalence about Daley’s policies seemed to resolve itself by the time he set his sights on the White House. But Obama’s reluctance to embrace the Daley mystique in 2003 reflected perhaps his rather privileged glimpse into the underside of the Chicago success story. In 2002, for example, Chicago’s 647 homicides made it the murder capital of the country, and two of its highest-profile murders that year occurred in the North Kenwood–Oakland area of Obama’s own Thirteenth Senate District, where a brick-wielding mob of youths had beaten two men to death after their van had lost control and struck a group of young women sitting on a porch.14

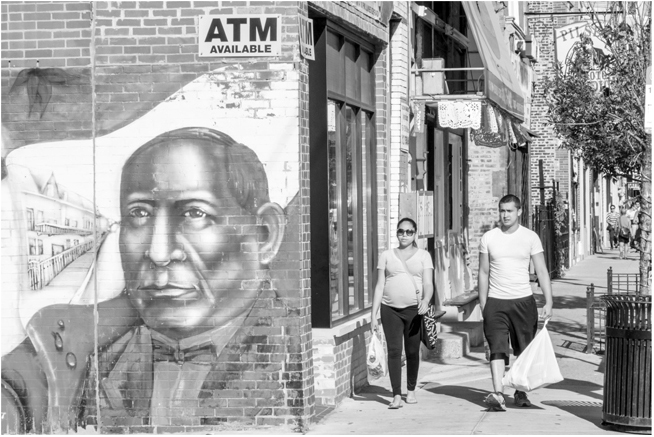

This was merely one in a series of brutal murders perpetrated in Chicago’s black ghetto neighborhoods that received national exposure in the first decade of the twenty-first century, each incident reminding white Chicagoans of the other world they sped through in the sealed safety of their automobiles on the Dan Ryan, the Skyway, and the Congress Expressway, or else in an “L” train rattling westward or southward from the Loop. During Congressman Bobby Rush’s highly ineffective 1999 mayoral primary run, which culminated in his crushing defeat by Daley by a 73–27 margin, the former Black Panther had tried to arouse the ire of blacks and liberals alike by evoking the idea that there were, in fact, two Chicagos: “One Chicago is symbolized by flower pots and Ferris wheels and good jobs and communities where police respect the citizens,” Rush had claimed, making reference to Daley’s massive program to beautify the city’s tourist areas and his $250 million renovation of the Navy Pier lakefront recreation and entertainment area, with its 150-foot-high Ferris wheel. “The second Chicago is still plagued by a lack of jobs, poor schools and police less tolerant of youths who dress and talk differently than they do.”15 If this message posed little threat to the seemingly invincible Daley and his Chicago success story on the citywide stage, it no doubt played a role in Rush’s reelection to the House of Representatives the following year, when he collected twice as many votes as his challenger in the Democratic Primary—an ambitious state senator named Barack Obama.

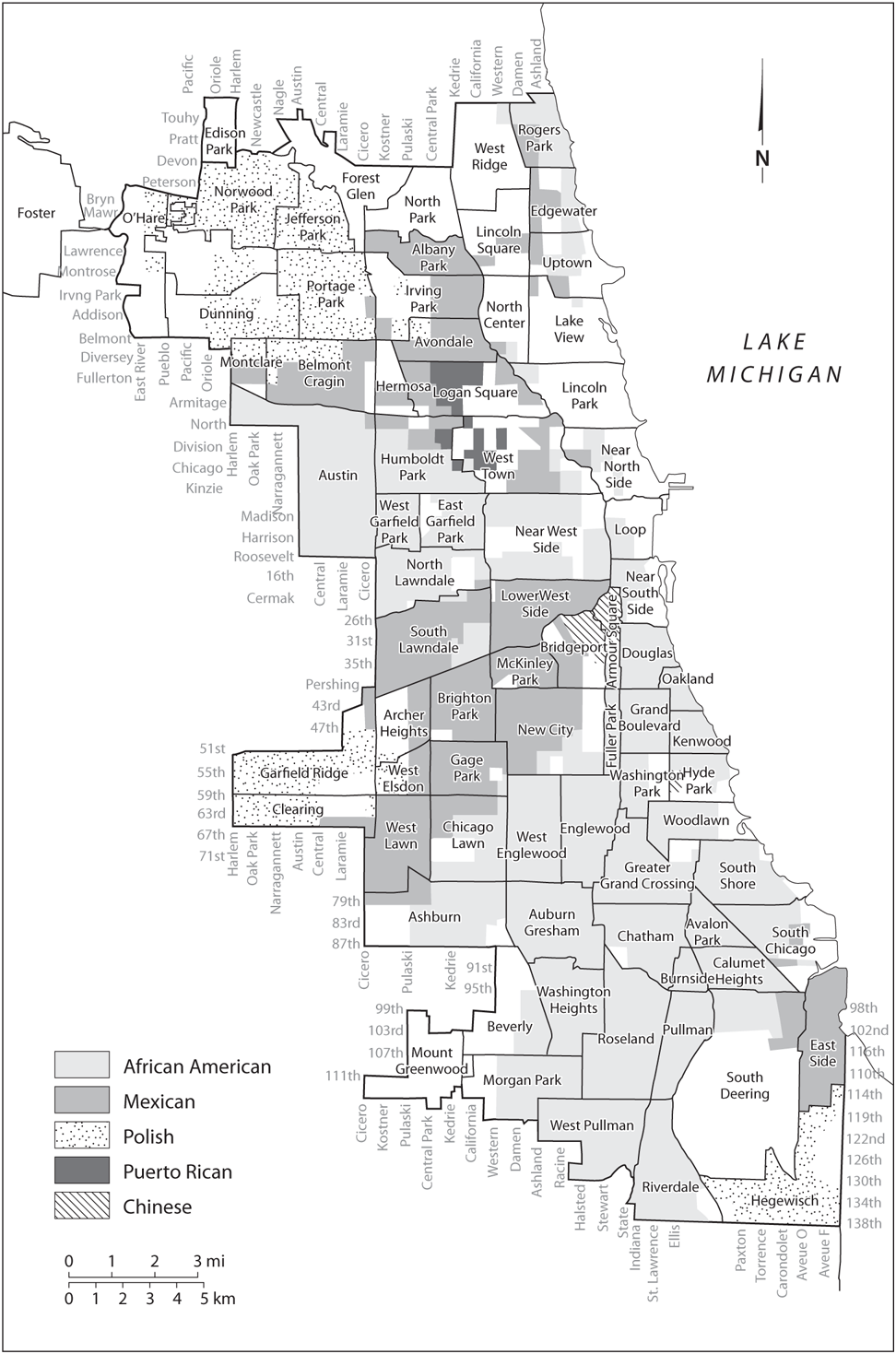

When the figures from the 2000 census appeared, few could take issue with the veracity of Rush’s claim. According to the new census data, Chicago had managed to retain its middle class during the 1990s; its median household income had grown at a rate that was twice the national average; and overall poverty had modestly declined—all of which seemed to confirm the triumphant image of Chicago as a leading global city and tourist destination, up there in the top tier with the likes of New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston. But the data from the “second Chicago” offered a very different vision. The census readings related to black Chicago and to its astonishing disparity from white Chicago showed a city more statistically akin to the nation’s most distressed urban centers: Baltimore, Newark, St. Louis, New Orleans, and Detroit. While the median household income for whites and Latinos in Chicago was $49,000 and $37,000, respectively, it was just $29,000 for blacks, and only 13 percent of black adults held bachelor’s degrees, compared to 42 percent of whites.16 Such disparities helped to explain why Chicago’s 50.2 percent employment rate for black males over the age of sixteen put it just barely above New Orleans and St. Louis and well behind Baltimore (54.4) and Newark (54.2). Moreover, Chicago topped all other major metropolitan areas for its percentage of black residents having no access to telephone service (7.2), with Detroit a somewhat distant second. Perhaps most tellingly, African Americans were just 19 percent of the overall population of the Chicago metropolitan area but 43 percent of the population living below the poverty line, figures that placed the city ahead of every one of the fifteen largest metropolitan areas except for St. Louis in this statistical measure.17

FIGURE 17. The other Chicago: view north along S. Dearborn Street towards the Robert Taylor Homes on E. 54th St. in 1998. Photo by Camilo José Vergara. Reprinted with permission.

Such figures tell only part of the story. They say little, for example, about the street culture and underground economy that so powerfully shaped the life chances of a generation of youths coming of age in the second Chicago. One of the major consequences of the festering poverty was the development in the late 1980s and 1990s of a Hobbesian world of ruthless street gangs engaged in a battle to the finish for control of the lucrative crack cocaine trade that exploded across the American urban landscape in the second half of the 1980s. By the early 1990s, several of the city’s mightiest gangs—the Gangster Disciples, Vice Lords, Saints, and Latin Kings, among others—had set up elaborate centralized, hierarchical organizations to administer crack distribution in their respective territories. The business approach they came to adopt resembled the franchise model of the fast-food restaurants that were quickly becoming the only sources of nourishment in their communities: gang leadership distributed product to a number of competing “crews” within the general organization, each of which controled its sales methods and wages so as to maximize its profits after paying “dues” and “street taxes” to the central leadership. The arrangements amounted to a neoliberalism of the streets. Researchers studying the underground drug economy of this moment even observed subcontracting schemes, in which one gang leased a building or street corner to another for the purposes of drug trafficking within its territory. Since crack was normally distributed in small quantities with low purchase costs, the business tended to be labor intensive, requiring countless hand-to-hand transactions and numerous foot soldiers to make the sales, watch for police, keep track of the money, and, when need be, engage in turf battles. Even though estimates of total drug trafficking revenues in the city of Chicago ranged from $500 million to $1 billion, investigative journalists and ethnographers alike determined that the many thousands of foot soldiers—mostly teenagers pursuing hip-hop video dreams laden with Mercedes Benzes and Cadillac Escalades, gold chain necklaces, swimming pools, and shapely women—earned wages just a bit above those offered at McDonald’s and KFC.18

Yet, despite the disadvantageous risk-reward ratio associated with entry-level work in a crew, gangs were incorporating—if not by financial inducements, then by force and intimidation—increasing numbers of young men into their ranks. In 2006, a Chicago Crime Commission study estimated that some 125,000 youths—more than a quarter of the total number of students within the entire Chicago public school system—belonged to between seventy and one hundred gangs within the city, a sharp rise from the previous count of 70,000 gang members in 2000.19 It was this trend more than anything else that accounted for Chicago’s top rankings among the nation’s ten largest cities in rates for both violent crime and homicide. Between 1992 and 2004, the share of murders within the city that were “gang-motivated” rose from 15 percent to more than 35 percent, while the average age of the victims of gang-motivated homicides dropped significantly.20 During the 2008–2009 school year, a record forty-three Chicago public school students became the victims of gang-related murders, a situation that gained national attention in September 2009 after the brutal murder of sixteen-year-old Derrion Albert, a solid student who had managed to stay clear of gang activities. The Albert affair attracted national and even international coverage through a mobile-phone video of his savage beating during a wild street fight between opposing neighborhood gangs in the far South Side Roseland area—one from around Fenger High School, where Albert had been an honor student, and one from the Altgeld Gardens Housing Project, where Barack Obama had worked as a community organizer in mid-1980s.21 The video shows Albert, who had apparently walked into the fracas by chance, knocked to the ground by a youth swinging a long wooden board and then bludgeoned and stomped on repeatedly by several others, amidst the screams of female onlookers, who eventually tried to drag the boy to safety.

This scene of unspeakable horror belies or at least complicates the idea, heard in urban policy circles beginning in the late 1990s, that the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) under Mayor Daley’s management had become what President Clinton referred to in 1998 as “a model for the nation.” Once dubbed the “worst in the nation” by President George Bush’s secretary of education William Bennett in 1987, Chicago’s schools had been, by many accounts, transformed after 1995, when the Illinois state legislature handed complete control of the CPS over to Mayor Daley. With Gerry Chico as the president of the CPS and Paul Vallas its CEO, the Daley administration implemented a sweeping corporate-style reform that imposed centralized authority over the elected, neighborhood-based Local School Councils (LSCs) established during the Washington years, created a range of special schools and programs, and, perhaps most importantly, ushered in an unforgiving system of accountability based on student performance on annual standardized tests.22 It was precisely the kind of model that the Bush administration looked to when it designed its No Child Left Behind program, which, after being legislated by Congress in 2001, required all government-run schools receiving federal funding to administer a statewide standardized test in order to evaluate performance. Any school failing to achieve acceptable results after a number of years faced a range of “corrective actions,” from curriculum and staff changes to major restructuring measures, including subcontracting its administration to a private company. Several years after its inception, Chicago’s program appeared to show some significant results. Between 1995 and 2005, the graduation rate increased from under 42 percent to 51 percent, which moved Chicago from the lower ranks into the middle of the pack of the nation’s big cities.23 Moreover, between 2004 and 2009, the rate of CPS graduates enrolling in college rose from 43.5 to 54.4 percent, a jump that more than tripled the 3.4 percent rise nationally.24

And yet such signs of progress pointed to the creation of a multitiered educational system rather than any wholesale improvement. If the Chicago school reforms of the mid-1990s had played a role in increasing the percentage of high school graduates heading off to higher education, they had done little to diminish the city’s sizable share of the country’s most troubled high schools. According to high school rankings compiled in a 2009 study based on standardized test scores, Chicago possessed seventeen of the one hundred worst performing schools in the United States. New York, by contrast had three, and Philadelphia and San Francisco one each.25 With only 4 percent of its students proficient in math and 9 percent proficient in reading, Derrion Albert’s school, Fenger, was twenty-fourth from the bottom—a situation that helps explain the scene that Albert walked into in September that year. Indeed, while an array of “college prep” magnet schools, charter schools, and high school International Baccalaureate programs had raised the educational bar for many middle-class Chicagoans, such new opportunities remained far out of reach for the vast majority of students.26 In working-class black and Latino areas of the city, access to the kind of public education that can qualify students for advanced degree programs was scarce. To take but one example, out of the total 11,915 spots available in the city’s nine selective college prep high schools in 2011, schools located in low-income black and Latino neighborhoods outside the North Side or immediate Loop vicinity provided only 2,670. And, while students were of course eligible to apply to schools outside their neighborhoods, if they could handle the long commutes, low-income students, who made up some 85 percent of the total student population in the CPS, constituted only about one-third of the enrollments in these North Side and Loop area schools that year.27 In effect, then, Mayor Daley’s celebrated reforms created a system of winners and losers, with the winners living predominantly in white, middle-class, and some gentrifying neighborhoods, and the losers concentrated in low-income black and Latino neighborhoods south and west of the Loop, where according to a 2003 report by the Center for Labor Market Studies, black males were six times more likely than their white counterparts elsewhere in the city to be out of school and unemployed.28

Certainly, the allure of the gangs and the absence of promising employment opportunities for young men in the ghettos and barrios loomed large in any explanation for this disparity. But there was also reason to believe that school policies implemented during Daley’s aggressive drive to boost test scores and hold schools accountable for poor performance played a role in pushing young men into the precarious place between school and work. A number of studies conducted between 2000 and 2003 revealed dramatic increases in school suspensions for minor nonviolent infractions. Between 1999 and 2000, for example, suspensions jumped from 21,000 to nearly 37,000, with students of color receiving the vast majority of them. Increasing suspensions, moreover, also meant more expulsions, with African Americans, according to a report published by the social service agency Hull House, being three times more likely than whites or Latinos to be expelled.29

These strategies of weeding out the students identified as bringing down the numbers gave way in 2006 to a new policy under Daley’s Renaissance 2010 plan to close some eighty poorly performing schools over four years and replace them with one hundred privately run charter or contract schools, whose teachers were not required to be certified by the state, received lower salaries, and were barred from joining the Chicago Teachers Union. This discovery of charter schools as the panacea for the city’s failing public education system represented the same logic of neoliberalization that was shaping the city’s approach to social services provision. Driving this scheme was none other than the Commercial Club, which constituted a committee of high-powered captains of industry and finance under the chairmanship of Exelon Corporation CEO John W. Rowe—including the chairman of the board of McDonald’s Corporation and the CEO of the Chicago Board Options Exchange—to design a private-sector answer to Chicago’s school problems. The report issued by this Education Committee of the Civic Committee of the Commercial Club was aptly named Left Behind. Journalist Rick Perlstein revealed that it “deployed the word ‘data’ forty-five times, ‘score,’ ‘scored,’ or ‘scoring’ 60 times—and ‘test,’ ‘tested,’ and ‘testing,’ or ‘exam’ and ‘examination,’ some 1.47573 times per page.”30 Within a year, Daley was moving on the Renaissance 2010 charter school initiative. Overseen by Arne Duncan, CEO of the CPS at the time, the implementation of Renaissance 2010 met fierce resistance from many LSCs objecting to the disruptions and violence caused by the often-precipitous school closures. In the initial phase of the plan, for example, a series of school closures on the South Side led to student transfers to neighboring areas, which, in turn, caused sharp spikes in gang violence. Community concerns like these, however, were clearly secondary to the objectives of raising scores and cutting costs. Further suggestive of the neoliberal rationality that infused the plan was a 2007 speech made by CPS president Rufus Williams in front of the Chicago City Club, a group of civic and business leaders, in which he compared the idea of LSCs running schools to a chain of hotels being managed by “those who sleep in the hotels.”31

Such policies—suspensions, expulsions, closures, and the dampening of local participation in the decision-making process—were components of a public relations campaign to manufacture evidence of progress resolving problems that had opened the city to widespread criticism in the 1980s and early 1990s, when a series of teachers’ strikes and parent-led community protests raised awareness about gang violence and of the lack of funding for necessary school improvements and salary increases. But they also spoke once again to the revanchist spirit of neoliberal governance that fed off the hard-edged antiwelfare, law-and-order rhetoric coming out of Washington during this same period. This was an approach and an ethos that circulated among policy makers in cities across the United States, but that saw perhaps its clearest expression in Richard M. Daley’s Chicago success story. One of the pioneering innovations brought about by Daley’s overhaul of the system in 1995 was the establishment of three military high schools as well as the dramatic expansion of military programs in numerous high schools and middle schools.32 Predominantly enrolling blacks and to a lesser extent Latinos, these military high schools, which used military-style forms of punishment for violations of school rules, achieved graduation rates and test scores that placed them in the top ranks of the schools available to working-class blacks and Latinos. But they were also living monuments to the idea that what was amiss in Chicago’s schools had more to do with the cultural shortcomings of black and Latino students than with the structural inequalities of the school system itself. All it takes is some military-style discipline, the argument went, to make things right.

A similar kind of rationale infused the move to orient the academic evaluation process around a standardized test. Yet, while Chicago school officials never missed a chance to remind people that all students in Chicago were evaluated by the same test—the “Iowa Tests”—and thus held to the same standards, the test in practice exacerbated already existing disparities between the city’s most elite schools, which were disproportionately middle class and white, and its lowest-achieving ones, which were overwhelmingly working-class black and Latino. In schools where scores were lowest, classroom time was dominated by lessons geared more towards test preparation than intellectual development. One researcher who sat in on classes in several such schools observed teachers making extensive use of materials on test-taking strategies, training students for hours on filling in multiple-choice bubbles, and having them recite slogans such as “three B’s in a row, no, no, no.”33 Understandably, such conditions contributed to higher dropout rates and disciplinary problems in poorly performing schools, whereas in schools with little risk of failure, teachers faced fewer test-related constraints and could more effectively orient their lessons to the interests and intellectual needs of their students.

In view of such glaring inequalities, it was becoming difficult to argue that Chicago’s school system represented a model to be emulated. And yet, while fewer and fewer observers seemed willing to make this case, some of the key ingredients in its so-called success story—the replacement of failing neighborhood schools with charter schools and the emphasis on standardized testing—were incorporated into President Obama’s education policy. Such circumstances beg the question of how, considering Chicago’s disproportionate share of the worst performing schools in the nation and its high rate of student homicides, the CPS had ever stopped being seen, as George H.W. Bush’s secretary of education William Bennett once referred to it, as the nation’s worst.

And how was it that the dire situation in the vast majority of black and Latino high schools did not stir up more opposition to Mayor Daley within these communities. Even when faced with an established black politician from the South Side like Bobby Rush—someone who, as a U.S. congressman, had earned political capital both locally and nationally—Daley still managed to capture around half of the black vote. Among Latinos, moreover, Daley’s support was so strong throughout his more than two decades in office that not a single Latino politician ever dared to make a serious run against him. These are questions that must be explored on a number of levels, and though this particular study has attempted to delineate a set of experiences that were somehow specific to the inhabitants of the 234 square miles of urban space that lie in the northernmost part of the state of Illinois, it is important to recall that Daley’s Chicago was embedded within a national political context that played a critical role in shaping the meaning of the circumstances transpiring within its borders. In other words, how working-class blacks and Latinos viewed their situation related, in part, to ideological currents that blew into the city from elsewhere—through their television sets, radios and stereos, computer screens, and telephones.

And what they increasingly saw and heard beginning in the late 1980s and continuing through the 1990s were images, stories, diatribes, polemics, and anecdotes that described the problems in their schools and neighborhoods as consequences of cultural deficiencies—of dysfunctional family situations and debased moral values—rather than as the by-products of economic marginalization and racial discrimination. Moreover, these were messages purveyed not merely by the right flank of the Republican Party. The antiwelfare crusade that began during the Reagan years had gained so much momentum that by the mid-1990s it had captured the nation’s entire political center. It was a Democratic president, Bill Clinton, in fact, who signed the famous 1996 Welfare Reform Act (officially known as the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act), which, as he proclaimed, “end[ed] welfare as we know it,” a move that followed his active sponsorship of the largest federal crime bill (the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act) in U.S. history. With the Republicans under the leadership of Newt Gingrich regaining both houses of Congress in the 1994 midterm elections, Clinton sought to steal their fire by keeping pace with their calls for a tougher approach to law enforcement and an end to a welfare system that had destroyed values of “personal responsibility” and hard work. The two pieces of legislation amounted to a continuation of the Reagan Revolution’s dramatic shift of federal funds from social spending to law enforcement—a trend that played a leading role in increasing the kinds of racial disparities in Chicago that had been so glaringly revealed by the 2000 census.34 And yet in the national discussion about the persistence of such racial inequalities, notions of “personal responsibility” and cultural deficiencies took center stage, pushing to the margins analyses focusing on the forces of racial discrimination.

Making matters worse was the fact that some of the most prominent voices arguing for a cultural interpretation of black inner-city poverty came from a number of black intellectuals who had themselves risen out of such conditions—scholars like Shelby Steele and Thomas Sowell of Stanford’s conservative Hoover Institute and the University of Chicago’s famed sociologist William Julius Wilson.35 That Wilson, a self-proclaimed “social democrat” favoring aggressive Great Society–style intervention in the urban labor market, found himself grouped with strident conservatives like Steele and Sowell was a sign of just how compelling the culture-of-poverty argument was to Americans in the late 1980s and 1990s. Wilson’s primary objective in both his landmark 1978 book The Declining Significance of Race and in his 1987 study The Truly Disadvantaged was to argue for class-based social policies that were better adapted to the specific circumstances of poverty faced by a black underclass trapped in spatially and socially isolated ghettos with poor schools and scarce job opportunities.36 But by making the corollary argument that fighting racial discrimination was no longer as necessary as it had been in the past, he left himself open to charges that he was minimizing racism as a cause of ghetto poverty, and in delineating the distinct conditions of black underclass poverty—single-parent families, juvenile delinquency, academic failure, the lack of positive role models, and the breakdown of community institutions—he seemed to some observers to be straying too far on to the well-worn ground of culture-of-poverty pathologies. Wilson, who served as an informal advisor to Bill Clinton during his first term and as a consultant to Mayor Daley, appeared to be telling Democrats to move past the kind of divisive race-based policies (for example, affirmative action) that had caused the defection of white middle-class moderates from the party since the late 1960s. Conservatives, for their part, were thrilled by Wilson’s apparent minimization of racism. Of course they were distorting his argument, and Wilson himself cried foul in a number of high-profile interviews, but the fact remained that a Chicago-based, black social democrat with impeccable academic credentials who had been raised by a single mother on welfare had signed his name to an award-winning book entitled The Declining Significance of Race.

MANAGING THE MARGINALIZED

The views of prominent black conservative scholars like Steele and Sowell and of somewhat misunderstood liberals like Wilson were less consequential to ordinary Chicagoans of color than the more popular ideological currents and political movements circulating through their neighborhoods. In the early 1990s, Chicago was at the center of what was then and still is the largest single mass mobilization in the black community since the era of civil rights—the Million Man March on Washington, DC, in 1995. Organized by Chicago-based Nation of Islam (NOI) leader Minister Louis Farrakhan, the march was called in an effort to “convey to the world a vastly different picture of the Black male” during a moment when law-and-order politicians and the culture industries alike were painting black youths as gangsters and drug dealers.37 The idea for the march took shape shortly after the Republican takeover of Congress, and march organizers sought to use the mobilization to register black voters for the next elections and draw attention to issues facing black communities. Yet such political projects were subsumed by the overriding messages of personal responsibility, self-help, and spiritual atonement. In effect, ordinary African Americans were being told to mobilize collectively against racism but that the real path to their salvation was not political but rather spiritual and, above all, personal.

This package of ideas had been assembled on Chicago’s South Side, in the Nation of Islam’s headquarters at 7351 South Stony Island Avenue, where, since the mid-1980s, Farrakhan had been drawing increasingly large audiences to his mosque to hear elaborate rants sprinkled with anti-Semitism, homophobia, and a range of conspiracy theories. Nor was this recipe unique. About twenty blocks southwest of NOI headquarters, Reverend Jeremiah Wright had been touching on some similar themes—if in less sensationalist and provocative terms—in sermons from the pulpit of Trinity United Church of Christ. By the early 1990s Wright’s charisma had enabled him to amass a congregation of several thousand members—University of Chicago law professor Barack Obama and his wife, Michelle, among them. To be sure, Obama and many of his fellow congregants at Trinity would have been loath to think of themselves as somehow associated with the NOI, but it was hard to deny that Wright and Farrakhan belonged to the same context. It was not by chance, for example, that the two South Side religious leaders shared the stage at the Million Man March. But while Wright was rapidly becoming a powerful local figure, presiding over a congregation of more than six thousand by the time he retired in 2008, Farrakhan was moving into the national spotlight. By the early 1990s, the Nation of Islam’s membership was increasing nationwide, Farrakhan’s outrageous declarations about Jews and UFOs were making tabloid headlines, and a number of enormously popular rap artists, such as Public Enemy, Ice Cube, and X-Clan were incorporating excerpts of the NOI leader’s speeches into gold- and platinum-selling albums. And yet rap and the NOI made rather strange bedfellows. If a new generation of West Coast “gangsta rappers,” like NWA (Niggas With Attitude) and Ice Cube, had offered some penetrating critiques of what the Reagan Revolution’s vision of law and order had meant for a generation of black ghetto youths, by the time of the Million Man March, the images of criminality, violence, sexism, and immorality purveyed by rap music and videos had become a big part of the problem that the movement’s organizers were seeking to address. “By the summer of 1993 gangsta rap had been reduced to ‘nihilism for nihilism’s sake,’” writes historian Robin D.G. Kelley, and this sense of nihilism—much like the message of personal responsibility that stood dialectically opposed to it—only provided further confirmation for those claiming that black inner-city poverty was a cultural rather a structural issue.38 Nihilism, dysfunction, and pathology were the terms that defined the problem of black underclass poverty throughout the 1990s and into the early years of the twenty-first century. That even the eminent radical black activist and philosopher Cornel West would peer into the heart of the black ghetto and see a world of “nihilism,” as he did in his classic 1994 Race Matters, reflected a profound loss of faith in the political system among working-class blacks and their leaders across urban America.39

But in Chicago, in particular, where voter turnout was reaching new lows and mayoral elections were considered local jokes, the pessimism about the possibility of political solutions to the problems people faced in their daily lives was especially pronounced—a situation that seemed all too apparent during Bobby Rush’s uninspiring campaign of 1999. There were glimmers of hope from time to time, as when blacks turned out in 1993 to help elect the first black woman to the U.S. Senate, Carol Moseley Braun. However this was state and not local politics, and Moseley Braun was, in some sense, a gift from Daley, who not only endorsed her but also convinced many of his deep-pocketed donors to throw their financial support behind her as well. This was, in part, payback for services already rendered; in 1989, as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, Moseley Braun had given her own endorsement to Daley, a deed she repeated in 1995.40

Another moment of political possibility, moreover, appeared to be developing in the months leading up to the 1995 aldermanic elections, when, out of the deepest reaches of apparent black underclass nihilism—the impoverished neighborhoods around the Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago’s Third Ward—an insurgent poor people’s movement crystallized around the candidacy of former Gangster Disciple (GD) Wallace “Gator” Bradley. The financing, manpower, and guidance behind Bradley’s campaign came from a political organization called 21st Century Vote, which Gangster Disciple kingpin Larry Hoover had launched in 1990 from a high security federal prison while serving a sentence of 150 to 200 years for murder. Hoover was running with the GDs in the late 1960s, when some of Chicago’s most fearsome gangs were trying to transform into political organizations, but his own personal awakening came not on the streets of Englewood but in a number of prisons, where he earned his GED and remade the Gangster Disciples into a political organization he called Growth and Development. While critics would maintain that Hoover’s turn to politics was a cover for his continuing leadership of the GDs’ massive drug trafficking enterprise, a taped telephone conversation between Hoover and Vice Lord leader Willie Lloyd in 1992 revealed an ambitious plan to mobilize “the poor people” around the housing projects, including the “dope fiends and wineys,” in order to take the aldermanic seat from Daley-backed Dorothy Tillman. In 1993, the organization moved into a second-floor office above an abandoned storefront in Englewood and promptly organized thousands of youths to march on City Hall to prevent the closing of some neighborhood health clinics and help settle a teacher’s strike; a year later, 21st Century Vote had registered several thousand voters and had raised well over $100,000 from mostly small donations. Yet, although Bradley was able to get national attention by forcing a runoff with Tillman, African Americans in the Third Ward were not ready to believe that gangbangers could become community leaders, and the thousands of Gangster Disciples who hit the streets for Bradley only seemed to make matters worse. Bradley lost badly in the general election, and 21st Century Vote faded into insignificance.41

The story of Larry Hoover and 21st Century Vote provides some insight into how Mayor Daley could have presided over the two Chicagos while arousing so little agitation from those living in the subaltern one, the Chicago of litter-strewn vacant lots, boarded-up buildings tagged with gang symbols, impossibly high unemployment, and gunshots piercing the night. If the term machine does not do justice to the sophisticated mechanisms of social control that characterized the administration of Richard M. Daley, countersubversive tactics that resembled those from the glory days of Richard J. Daley’s machine were certainly called to service in response to Gator Bradley’s challenge. The police turned up the heat on the Gangster Disciples in the days before the election with roundups and other forms of harassment, and from the beginning the Chicago press seemed much too zealous in its demonization of Hoover. Prior to one of Hoover’s parole hearings, for example, a Tribune editorial argued, “Hoover is a leader, all right. He helped lead neighborhoods down a self-destructive road of murder, drug abuse and despair. His release would undermine the authority of law-abiding folks who lead by example, yet don’t get a parade of politicians to sing their praises.” Whether City Hall had played a role in the Tribune’s crusade against Hoover we will never know for sure, but we do know that city officials came to every parole hearing to insist that Hoover was still the gangster he had always been.42 However, Hoover and his ragtag band of lumpenproletariat was all too easy for Daley to contain. Harder to explain was Daley’s role in anesthetizing the injuries of the city’s other half and paralyzing any forces of political opposition amidst a series of scandals, any one of which might have been enough to bring another mayor to his knees.

In late 1995, just months after the Daley administration had displayed its callous attitude towards the poor during the heat wave, a massive FBI sting known as Operation Silver Shovel revealed a culture of rampant corruption within Daley’s City Hall, including bribes for city contracts, fraud, money laundering, drug trafficking, and organized crime activity. The more than 1,100 wiretap recordings made during this operation showed that everyone around Daley seemed to be on the take, and these were hardly victimless crimes. Chicago residents, whose property taxes were on the rise in the 1990s, had for years been paying what amounted to a “contract corruption” tax, and minority-owned contractors, which had enjoyed an affirmative action program put in place during the Washington years, were no longer seeing their rightful 24 percent share of the city’s construction business because of a range of fraudulent practices. In one of the worst cases, James M. Duff, one of the heads of a reputed organized crime family and a big financial supporter of Daley, had convinced an African American employee to pose as majority owner of one of his waste management companies in order to win a contract intended for minority-owned businesses.43

During this time, moreover, a series of investigations began to uncover a hideous pattern of police torture at the city’s South Side Area 2 police station, where, it was later determined, 137 African American men were tortured into confessions on the orders of police lieutenant Jon Burge between 1972 and 1991. Detainees had reportedly had plastic bags placed over their heads, guns shoved in their mouths, and electrical shocks and cigarette burns administered to their ears, nostrils, chests, and genitals. Daley was not mayor while most of this was going on, but as Cook County state’s attorney in the early 1980s, he had been informed of such practices by reliable sources and had refused to launch an inquiry. Based in part on the revelations of these coerced confessions, Illinois governor George Ryan halted all executions in the state of Illinois in 2000, and three years later commuted the death sentences of 167 prisoners on Illinois’s death row while pardoning four death row inmates tortured at the Area 2 station. Ryan’s bold moves, however, did little to change the killing going on in the streets. In 2001 and then again 2003, Chicago made headlines as the “murder capital” of the United States, registering more homicides than the significantly more populous cities of New York and Los Angeles.

In January 2004, City Hall was ensconced in scandal once again, when the Chicago Sun-Times discovered serious improprieties in the city’s $40-million-per-year Hired Truck Program. Trucking companies with ties to both organized crime and high-ranking city officials were being awarded lucrative contracts for doing little or no work, and while nothing could be directly pinned on Daley, there was too much circumstantial evidence to dismiss. Some 25 percent, or $47.8 million, of all Hired Truck money went to companies from Daley’s Eleventh Ward power base, companies in the program had contributed more than $100,000 combined to Daley’s campaigns, and Daley’s brother John had underwritten insurance policies for a handful of them.44 As federal prosecutors continued on with the Hired Truck scandal, evidence surfaced that Victor Reyes, a close Daley advisor and head of the powerful Hispanic Democratic Organization (HDO), had rigged hiring and promotion exams to reward city workers, including members of the HDO, for their political activities on behalf of Daley and other candidates.

All this to say that between 1995 and 2005, there was almost never a moment in Chicago when the city did not seem, at least in the eyes of its mostly black and Latino low-income residents, to be a place of monumental injustice—where big businessmen, mobsters, and people with personal ties to the Daley family and its close friends got fat, while poor blacks and Latinos were being gunned down on street corners and tortured in the back rooms of police stations. Even if one could ignore the litany of corruption scandals that appeared in the pages of the dailies and utter, “That’s just the way it is,” Chicago slapped the have-nots in the face every time they ventured near the Loop. A simple drive north on Lakeshore Drive took one through the Chicago of clean, tree-lined streets, marinas full of shiny white pleasure boats, well-manicured green park spaces, tidy beaches with volleyball nets fronting a sparkling blue Lake Michigan, rapidly rising real estate values, and neighborhoods with names befitting the class of people living there: the Gold Coast, Lincoln Park, and Lakeview. The many thousands of residents in the Cabrini-Green Homes, a quadrant of mid- and high-rise block-like structures with fenced-in balconies, where the Gangster Disciples ran a drug trafficking operation that earned them an estimated $3 million per year before its demolition in 2010 and 2011, were just a short walk away from the upscale Gold Coast neighborhood. William Julius Wilson made an important point when he emphasized the social and spatial isolation of the black poor in Chicago, but one should not take this idea too far: African Americans in the city understood quite well how the other half lived. But even though poor people of color regularly confronted such “savage inequalities,”45 they showed little interest in addressing them by investing in the electoral process. In the mayoral election of 2007, for example, overall voter turnout was just over 30 percent, with 70 percent of blacks and 80 percent of Latinos casting their votes for Richard M. Daley. In 1989, by contrast, Daley had garnered under 10 percent of the black vote.

So what accounted for the lack of opposition to Daley among blacks and Latinos and his virtual invincibility at the polls over his more than two decades in office? Some of the explanation brings us back into the cogs of the political machine he inherited from his father. The tactics City Hall deployed against Gator Bradley, as well as the various illegal schemes that created both jobs and lucrative contracts for Daley supporters, reveal the workings of a political machine that resembled the one run by Richard J. Daley in the 1960s and 1970s. Also similar was the absolute authority Richard M. Daley wielded over his city council, which came in part from a 1978 law giving the mayor the power to fill city council vacancies. By 2002, he had appointed one-third of the members of the city council, which may help explain why he did not have to use his veto power even once between 1989 and 2005. As political scientist Dick Simpson’s research has found, two-thirds of the members of the city council voted with the mayor 90–100 percent of the time.46 These aldermen stood with Daley because, as in the old days, the mayor controlled a spigot of patronage funds for irrigating their wards. But even if the Hired Truck scandal seemed to indicate that, in spite of the Shakman decree, a system of jobs for political supporters was still in operation, what really moved things during the Richard M. Daley era was “pinstripe patronage”—contracts for lawyers, consultants, and various other service providers, as well as enormous infrastructural subsidies and preferential policies for the developers who erected the city’s office buildings and retail centers, as well as for the companies who filled them. It was in this area in particular that Richard M. Daley’s patronage machine represented something of a paradigm shift from that of his father. Pinstripe patronage, in the high times of the global-city era, was not about demanding small donations from thousands of loyalists and giving out contracts to put new toilets in City Hall but rather about attracting five- and six-figure campaign donations from multimillionaires in exchange for seven- and eight-figure contracts, new tax loopholes, and a range of lucrative subsidies. Even in his very first campaign, in 1989, Daley had amassed an unprecedented $7 million in donations, with some 30 percent coming from just 1 percent of his contributors. Moreover, in addition to traditional support from contractors and construction unions, some two-thirds of Daley’s donations came from law firms (like the famous Sidley & Austin, where Barack Obama met his wife, Michelle Robinson), banks, commodities and stock traders, businesses, and consulting firms enmeshed in the global economy.47

Moreover, if Richard J. Daley had used some accounting tricks to veil the city’s financial situation, his son took this practice to another level of sophistication. Critical to Richard M. Daley’s pinstripe patronage juggernaut, for example, was his tax increment financing (TIF) program, a labyrinthine public financing method that he used to create a virtual “shadow budget” of over $500 million—about one-sixth of the city’s total budget—to fund large development projects, infrastructural improvements, and beautification efforts.48 The original idea behind TIFs, which began to be increasingly adopted in municipalities across the nation in the 1980s with the drying up of federal urban renewal funds and sharp reductions in federal development grants, was to create a mechanism that would channel capital towards improvements in distressed or blighted areas where development might not otherwise occur.49 In a typical TIF program, property tax revenues in excess of the amounts determined to be needed within a certain geographical area are allocated to a special discretionary fund for “public” projects. The thinking is that these projects, in turn, will theoretically improve the area and thus lead to increased tax revenues that will replenish the TIF fund and likely add to it in following years. Yet like so many other progressive-minded policy approaches that arrived in postwar Chicago, the problem with Chicago’s TIF program was that City Hall took the money and ran away from the progressive goals attached to it, and it did so behind closed doors. In fact, TIFs, by nature, are ill-suited to socially progressive ends—the construction of affordable housing or the creation of middle-class jobs—because of their adherence to a commercial logic contingent upon sharp increases in property values.50 Making matters worse in Chicago was the way in which Mayor Richard M. Daley incorporated the TIF system into his pinstripe patronage machine. While TIF projects involving private companies had to be approved by a city council vote and thereby made public, the large portion of funds used for neighborhood improvements—new schools, sidewalk and street repaving, and the upgrading of park and recreation facilities, for example—were not subject to public scrutiny, allowing them to be used as patronage rewards to distribute among aldermen loyal to the Daley machine.

This lack of transparency enabled the creation of a public funding system that reinforced inequalities rather than ameliorating them, a situation that remained largely obscured until Ben Joravsky, a journalist for Chicago’s leading alternative newspaper, the Chicago Reader, managed to get his hands on some internal TIF documents. According to Joravsky’s investigative work, TIFs skimmed $1 billion in property taxes off the city’s revenues between 2003 and 2006.51 Indicative of how unevenly this money was spread across the city, in 2007 the downtown LaSalle/Central TIF district added some $19 million in revenues while the Roseland/Michigan TIF district—the area often referred to as “the hundreds,” where Derrion Albert was murdered—brought in a mere $707,000.52 Moreover, in 2009, a year in which Daley announced the need to eliminate jobs and cut back services because of a $500 million budget deficit linked to the country’s financial crisis, the city council voted in favor of allocating $35 million from the LaSalle/Central TIF district to subsidize the move of United Airlines into seven floors of the Willis Tower.53 City officials justified the offer by arguing that United’s presence in the Willis Tower, in addition to solving the embarrassing problem of vacant floors in Chicago’s most prestigious skyscraper, would bring some 2,500 jobs to the city. This was a far better deal for the city as a whole than the $56 million in public subsidies paid to Boeing in 2001, when it moved its headquarters from Seattle to Chicago, bringing some 450 jobs with it.54

As the enormous subsidies offered to Boeing and United reveal, the maintenance of Chicago’s image as a high-flying global city was a top priority for the Daley administration. In this sense, Daley was no different from his homologue in New York City, Rudolph Giuliani, who in December 1998 offered the New York Stock Exchange a historically unprecedented $900 million in cash along with a package of tax breaks and other subsidies to prevent its move across the river to New Jersey. Next to this, the money spent on Boeing and United seemed more than reasonable, and the addition of these high-profile corporations helped to offset the psychological blows of losing Amoco, Ameritech, and Inland Steel to corporate takeovers. City officials provided further justification by repeatedly referring to the rosy estimates of certain economists about the “multiplier effects” of having all these highly paid white-collar workers around the downtown area. During the United affair, for example, Second Ward alderman Robert Fioretti, whose jurisdiction stretches from the bustling Loop westward into the depressed area around East Garfield Park, argued that the airline’s employees would spend an average of $6,700 in the downtown area—on, presumably, martinis, steaks, athletic club memberships, and a range of elite services. But the multiplier effects of this consumption stopped well short of Fioretti’s constituents on the black West Side, where the challenge was to lure low-cost food retailers in order to combat the problem of “food deserts”—large areas in which residents have little or no access to healthy food sources.

This area of the city had been devastated in 2003, when just to the west of it, in West Garfield Park, candy maker Brach’s Confections, Inc., closed a factory that provided more than a thousand jobs. With one of its signature items, Candy Corn, a nauseatingly sweet, waxy-textured corn-kernel facsimile commonly eaten by children around Halloween, Brach’s did little to boost Chicago’s global-city credentials, so Daley was unwilling to offer more than $10 million to try to retain its one thousand jobs—not nearly enough to dissuade the company from moving its operations into Mexico. Ironically, this was about the same amount City Hall would draw from the Northwest Industrial Corridor TIF five years later at the request of a developer seeking to convert the abandoned Brach’s factory into a warehouse and distribution center, which, according to the developer’s own estimate, would provide just seventy-five permanent jobs.55 The project would, however, eventually pay for itself in future income tax revenue, much of which would find its way back into the Northwest Industrial TIF, where it would be spent, of course, at the discretion of City Hall.56

That more than $10 million was allocated to a project that promised to create just seventy-five jobs in an area whose 17.3 percent unemployment rate ranked among the highest in the city in 2007 and whose principal high schools, Marshall and Austin, reported attendance rates around 50 percent revealed that Chicago’s TIF program had become almost entirely unhinged from any reasonable notion of the public interest. And yet much of what made the city’s financing system patently unjust occurred under the radar. Unlike the machine of old, which was out on the streets taking bribes, pouring drinks, handing out turkeys, and dispatching thugs to make sure people voted “early and often,” Richard M. Daley’s well-oiled machine seemed to hum silently beneath the city. There were of course corruption scandals enough to raise eyebrows now and then, but it could be argued that these scandals, in the end, overshadowed and even legitimated the quasi-legal policies that were redistributing public capital upwards. That is to say, Operation Silver Shovel, the Hired Truck scandal, and many of the other tales of cronyism that made it into the dailies created a deeply flawed perception of Richard M. Daley’s “machine.” Mid-level city officials consorting with gangsters and taking middle-class bribes, private trucks idling in parking lots at a rate of $50 per hour, strings pulled to arrange jobs for political supporters—these scandals hardly scratched the surface of what was really going on with Chicago’s finances. They made Richard M. Daley’s administration look too much like Richard J. Daley’s machine, an idea that obscured how much the scale of injustice had changed since the early 1990s. And even if the TIF program enabled City Hall to veil some of its dealings, the details of the majority of expenditures were out there for everyone to see, provided they wanted to make the effort to do so.

But until the months before the mayoral election of 2007, when the whole country was reeling from the blow of the subprime mortgage crisis, few political organizations were willing to take on either the global city agenda or the neoliberal municipal policies that were imposing austerity on the poor and shifting so much of Chicago’s tax revenues to business interests downtown and elsewhere throughout the city. This was in part because, viewed from the perspective of its thriving downtown and surrounding areas, Chicago looked like a city that was clearly moving in the right direction. Mayor Daley had invested massively in both beautification initiatives and the upgrading of tourist attractions, especially around the downtown lakefront area, making Chicago a first-tier destination for both business travelers and tourists. In terms of beautification, City Hall pushed through a new landscape ordinance in 1999 that put more trees on sidewalks, more flower beds on the medians of avenues, more planters in commercial districts, and obligated developers and builders to incorporate aesthetically pleasing landscaping into their designs. Mayor Daley’s drive to beautify the city was so consuming that after visiting Paris, he ordered the installation of lights on the city’s bridges and skyscrapers in order to give Chicago a Paris-by-night feel.

His efforts to improve the city’s tourism infrastructure were nothing short of staggering: In 1991, a new baseball park for the White Sox opened thanks, in part, to $81 million of city financing. Between 1992 and 1994, City Hall kicked in some $35 million in infrastructural costs for the construction of the United Center, the new home for the Chicago Bulls professional basketball team. In 1995, it allocated $250 million for the renovation of Navy Pier. In 1996 it completed a $675 million expansion of McCormick Place, giving the city the most square footage of convention space in the nation. In 1998 it spent $110 million to reconfigure Lake Shore Drive in order to create a “Museum Campus” that gathered Soldier Field (the stadium of the Chicago Bears), the Shedd Aquarium, the Field Museum of Natural History, and Adler Planetarium on one massive green space by the lake. In 2003 it financed a $680 million renovation of Soldier Field. In 2004 it inaugurated the $475 million ($200 million of which came from private donations) Millennium Park, a spectacular twenty-five-acre green space bordering the Chicago Art Institute to the north and Grant Park to the west that includes the three-story polished stainless steel bean-shaped Cloud Gate sculpture, the fifty-foot-high interactive glass brick Crown Fountain, a 2.5-acre flower garden, a large outdoor ice skating rink, a 1,500-seat performing arts theater, numerous spaces for art expositions, and its centerpiece, a state-of-the-art outdoor music pavilion crowned with a spectacular stainless steel bandshell designed by Frank Gehry.57 In 2005, the Federal Aviation Administration approved an estimated $6 billion plan by the city to expand O’Hare Airport’s capacity by 60 percent. And in 2007, Chicago opened yet another addition to McCormick Place, the $850 million McCormick Place West building.58

All this was of course part of the global-city agenda laid out by the mayor’s planning advisors in the 2002 Chicago Central Area Plan, which called for a downtown district of revitalized green spaces, promenades, and waterfront attractions. “Chicago,” the plan asserted, “will retain its role as one of the world’s great crossroads cities, attracting businesses, residents, and visitors internationally. . . Its Central Area will be a preeminent international meeting place, easily accessible from major destinations around the globe via expanded O’Hare International and Midway Airports.”59 What was taking shape so spectacularly along Chicago’s lakefront was part of a larger trend of urban revitalization that grew out of the convergence of the new economy of tourism and the global-city agenda. One result was the development of what political scientist Dennis Judd refers to as a “tourist bubble”—an upscale commercial district in which “tourist and entertainment facilities coexist in a symbiotic relationship with downtown corporate towers.”60 All one needed to do was to take a long stroll down Michigan Avenue from the area around the John Hancock Center and the Water Tower Place shopping center all the way across the Chicago River to Millenium Park to understand Judd’s point. In this tourist-friendly swath of the city, restaurants, shopping centers, cafés, and bars catered to both tourists and daytime professionals. And yet there was much more to the overall plan than this. Chicago’s massive capital investments in its tourism and business services infrastructure during the 1990s, which helped make it the top business traveler destination and the fourth for overall domestic travel by 2002, were part of a larger strategy to assure economic growth in an era of advancing deindustrialization. According to one study, travel-generated spending increased the city’s sales tax revenues from $54 million in 1989 to $145 million in 1999. By 2007 domestic and international travelers to Chicago were spending more than $11 billion annually, a sum that contributed over $217 million in local tax revenues and generated some 130,000 jobs.61

This infusion of capital helped to offset the loss of about 100,000 jobs in the manufacturing sector between 1986 and 2000, and a good number of the new service jobs created went to the residents of the working-class black and Latino communities most affected by the forces of deindustrialization.62 This was a process that Daley’s school reform program promoted through its creation of several Education-to-Career Academies (ETCs), vocational high schools offering nonacademic concentrations in key areas of the tourist services sector such as secretarial sciences and hospitality management. Such structures of employment opportunity warn against taking too far the idea of an impenetrable barrier between the downtown business district and the other Chicago where low-income blacks and Latinos live. Every morning, thousands of people from these communities commuted into the Loop and its surrounding areas to work in office buildings, restaurants, hotels, bars, cafés, retail stores, and a range of tourist venues. To be sure, the service jobs they performed, on average, paid much less than the manufacturing jobs they replaced; a study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Labor in 2001, for example, found that while the average annual salary for Cook County manufacturing workers was $40,840, service-sector workers took home a significantly lower $32,251, and retail workers earned just $17,045.63 But these jobs helped to stave off the worst in the other Chicago, extending lifelines into Latino and black communities facing 20 percent unemployment rates. The political stability prevailing in Chicago between 1989 and 2006 would have been unthinkable without the fantastic growth in tourist and business-traveler spending, which dipped sharply after the World Trade Center attacks of September 11, 2001 but then quickly rebounded after 2002.

In addition, at least some of the billions of dollars that City Hall poured into its infrastructural projects in the late 1990s and early years of the twenty-first century found its way into black and Latino communities—another reason why Daley’s electoral coalition held together so well. While African Americans and Latinos never received their rightful shares of city business, Daley was careful to spread just enough patronage into these communities to preempt charges of racism. During his first decade in office, for example, blacks, who constituted around 36 percent of the population and 40 percent of the city council membership, represented about 33 percent of the municipal labor force, and black-owned companies secured between 10 and 12 percent of city contracts. Latinos, by comparison, who constituted 28 percent of the population but held just 11 percent of the city’s jobs and procured 14 percent of its contracts, seemed to have fared rather poorly. But these numbers represented enormous gains from the Harold Washington years, when they procured a mere 4 percent of city contracts and 5 percent of city jobs.64 And when complaints about such arrangements arose, as they did especially in some quarters of black Chicago, those responding to them were likely to be high-ranking blacks and Latinos within Daley’s cabinet.

Political scientist Larry Bennett has argued that one of the main pillars of Daley’s approach to governance was “elite social inclusivity.”65 Unlike his father, for whom, in the oft-quoted words of his press secretary Frank Sullivan, “affirmative action was nine Irishmen and a Swede,” Richard M. Daley was the first white mayor in Chicago to appoint significant numbers of blacks, Latinos, and Asians to high-profile positions in his administration. This was an objective the mayor had pursued since his first days in office, when the Chicago Tribune declared a “rainbow cabinet” had been installed in City Hall.66 By 2006, Daley’s cabinet contained seven African Americans (17 percent), 24 whites (59 percent), 7 Latinos (17 percent) and 3 Asians (7 percent), with blacks and Latinos compensating for their relative underrepresentation by their presence in some highly visible posts. Daley’s public relations savvy dictated that minority appointments be deployed strategically to those areas of city government most liable to come under public criticism from minority groups. His appointees for president of the Chicago Board of Education, for example, were always black or Latino, as were his human resources (or personnel) commissioners, and an African American served as his press secretary—the all-important face of his public relations apparatus—throughout Daley’s twenty-two years in office.

What was being so brilliantly accomplished in all this—in the ward-level distribution of TIF funds for the benefit of local political leaders and business elites, in the parceling out of a quarter of the city’s contracts to minority-owned business, in the maintenance of appropriate levels of minority employment in the city’s workforce, and in the appointment of enough high-level minority officials to give blacks, Latinos, and even Asians the feeling of political representation—was what historian Michael Katz has termed “the management of marginalization.”67 Katz invokes the idea to help explain why U.S. cities witnessed relatively few outbreaks of collective “civil violence” between the 1970s and the first decade of the twenty-first century. He argues that in an American urban landscape in which the geographical boundaries of race were no longer being challenged—as they were during the Second Great Migration of African Americans from the 1940s through the 1970s—municipalities managed to dampen political opposition by “selectively incorporating” middling segments of economically marginalized communities with financial rewards and limited political powers while criminalizing and controlling the unincorporated.