15 Simon Colton’s The Painting Fool

If you are not arguing about terms like art and creativity, then you are not talking about art or creativity.

—Simon Colton154

Simon Colton wants The Painting Fool to be “taken seriously as a creative artist in its own right.”155

When you sit for your portrait, you sit in front of a screen. The Painting Fool greets you with, “Thank you for being my model.”156 Like any human artist, The Painting Fool has moods, determined by the articles it’s been reading in the Guardian newspaper that day. Through its software, it carries out a sentiment analysis on the words, which makes it happy, very happy, sad, very sad, reflective, or experimental. It also extracts phrases that affect what it looks at as it reads other periodicals. In a way, it is seeking inspiration.

At this point, it may be in such a bad mood that it refuses to paint your portrait. If it decides to go on, it will assess your expression—smiling, sad, or whatever—using a neural network for facial recognition, which also associates your expression with an adjective denoting your mood. Additional software transfers the adjective to sequential graphic software. Further complex scanning of the developing image of your face enables The Painting Fool to select from 1,200 painting styles, plus nine means for expressing them, including simulations for pencil, pastels, and paints. It creates a sketch of the sitter’s face in two to three minutes, then fills in the portrait. This can take up to fifteen minutes if the software is simulating acrylic paints, which take longer to dry. Then The Painting Fool runs the finished portrait back through the neural network to check whether it has caught your likeness and the facial expression it wants. If not, it has another go.

Then it sets to work to create a background, depending on its mood. It can choose from over a thousand abstract images taken from art and calculated to project different moods, plus image filters linking the mood to the face, resulting in about nine million choices. Out of these, The Painting Fool chooses the most appropriate background image, as shown in figures 15.1 and 15.2. Colton is “constantly surprised about what ends up in the background scene which doesn’t actually exist,” he says.157 Could this be considered evidence of the software’s imagination?

Happy face (left). As rendered by The Painting Fool, in vibrant pastels, with an “electric” background, 2015 (right). [See color plate 4.]

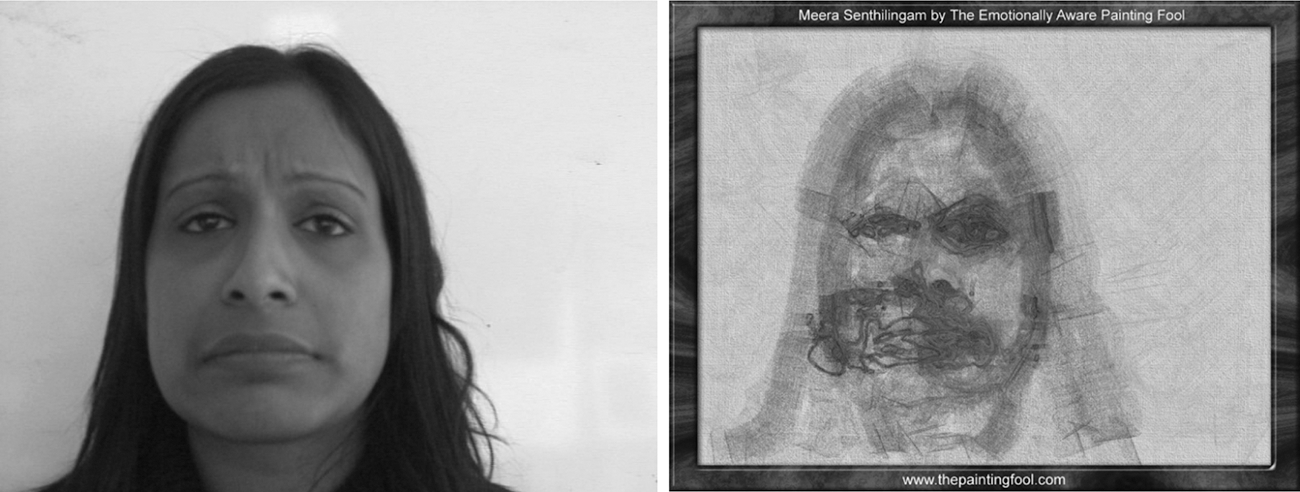

Sad face (left). As rendered by The Painting Fool, in muted colors, with a dull background, 2015 (right).

What if the machine was in a sad mood and the subject insisted on a portrait? The result might be a smiling face with a subdued background, perhaps in grey instead of brightly colored pastels. The software has even worked out that if it wants to produce something psychedelic, it shouldn’t use shades of grey. “I didn’t teach it that,” Colton says.

Colton is a professor of digital games technologies at the University of Falmouth and of computational creativity, games, and artificial intelligence at Queen Mary University of London. For him, the two are connected. He thinks in terms of seeing and creating connections between different disciplines. He peppers his conversation with examples from art, including his thoughts on machine creativity, a field in which he is something of a guru.

As a graduate student, Colton created an algorithm that could produce mathematical theorems. He called it the HR Tool, after the great mathematicians G. H. Hardy and Srinivasa Ramanujan. When he set it to multiply two numbers together, on returning to the machine ten minutes later it had discovered certain arcane mathematical properties. If a child had made that discovery, Colton argues, “we would describe the child as imaginative (or at least inventive).”158 In which case, why not say that the machine too might have imagination?

To explore machine creativity in art, Colton developed The Painting Fool, which he describes as an “art project rather than a scientific project.”159 He wanted to explore intentionality. Could the machine actually intend to paint a portrait in a particular manner? He also inquired whether the software could be said to have “struggled, with a fair meaning of that word.”160

He specifically did not set up The Painting Fool to mimic his own tastes and opinions as to what makes a painting pleasing. Rather he wanted to create software that actually showed intention and that “struggled” like a human artist.

Once the process starts, Colton has no idea what articles the machine has read or whether it will choose to use pencil, pastel, or paint. He claims that this “has changed many people’s minds about whether the software is just a mini-me.”161 He takes the artist Harold Cohen’s famous painting software—AARON—as an example. AARON produces paintings by putting together images that Cohen has fed into it, following certain rules for composition to create a sort of collage. In other words, it paints in the style of its creator.

Colton incorporates his HR Tool into The Painting Fool, which enables it to seek out new mathematical ways to shape the final painting; to some extent, it allows The Painting Fool to write new software. Colton depicts this as the software struggling, like a human artist. Although the program was created by Colton, The Painting Fool’s artwork is its own.

When the machine presents you with your portrait, on the back is commentary describing what mood it was in, what it was trying to achieve, and what it did achieve. Usually Colton lets the machine choose its own aesthetic, leaving it free to weigh alternatives, including its mood and method of producing the image, without any human intervention. He only curates the products when the work is to be exhibited in a gallery.162

Colton feels that a Turing-style test, attempting to determine whether a machine-generated artwork can be mistaken for a human creation, is asking the wrong question, making it seem that machine creativity aims to do no more than imitate human creativity.163 Surely we want to go beyond that. Bach and Picasso have already been done, by Bach and Picasso. It can be useful to create systems that produce work like theirs as a first step toward developing more sophisticated machines, but in the end even this may not be necessary when new and more advanced machines come online. Machines are silicon-based life-forms and may well come to produce art, literature, and music of a sort that we cannot even begin to imagine.

Colton is critical of deep neural networks that have to be fed an enormous amount of material to create their art. “More information about the world often means less imaginative thought,” he says. “It is difficult to imagine big data projects leading to the invention of imaginative ideas. In The Painting Fool project, we’re more interested in the simulation of particular behaviors associated with creativity, such as imagination, appreciation and intentionality.”164

Most people, Colton says, don’t own a work of art or a portrait of themselves, and many would like to. But they are expensive. “Software can fill the gap.” In the future, machines may well be able to produce interesting and affordable art for the masses. “Likewise,” he goes on, “people will realize the importance of human creativity when they see computer creativity; this will, in fact, encourage and raise their personal creativity.”

At the end of 2018, The Painting Fool became the world’s first digital artist in residence at Cardiff University’s Brain Research and Imagery Centre, thanks to the Wellcome Trust’s fund for public engagement. There it produced “a painting a day, including visualizations of brain scans and interpretation of brain data.”165

Over the one-year residency, Colton has worked to develop the machine further. He would like it to learn to change its own processes in creating art, to find its own material and paint a picture of that, and to be able to ask it why it painted a certain picture and what moved it to read a particular newspaper article. In general, he would like there to be more separation between it and himself as the programmer. Thus he has tried to work toward the computer creating autonomous work, “producing paintings [he] had never imagined.”166 According to Anna Jordanous, another prominent explorer of machine creativity, “Places like Tate Modern are beginning to take The Painting Fool seriously.”167

To sum up, although Colton created The Painting Fool, its art is its own, created without further human intervention. It also assesses that art. Surely both qualities can be defined as aspects of creativity. It even has moods. As to the argument that it is not out in the world and therefore cannot have the kind of experiences that we deem necessary for creativity, Colton responds that when it paints its subjects, it has experiences that are recorded by its software, just as visual images strike our retinas and are recorded in our brains.

Colton also thinks it’s irrelevant to compare computer to human art. He is adamant that it should be stated from the start that these are works produced by a machine. We should “be loud and proud about the AI processes leading to their generation. People can then enjoy that these have been created by a computer.”168